Abstract

Background

Information is limited regarding the knowledge and attitudes of physicians typically involved in the referral of patients for implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation.

Methods

We conducted a survey of primary care physicians and cardiologists at the University of Rochester Medical Center and the Unity Health System Rochester, NY from December 2008 to February 2009. The survey collected information regarding knowledge and attitudes of physicians towards ICD therapy.

Results

Of the 332 surveys distributed, 110 (33%) were returned. Over-all 94 (87%) physicians reported referring patients for ICD implantation. Eighteen (17%) physicians reported unawareness of guidelines for ICD use. Sixty-four (59%) physicians recommended ICD in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 35%. Sixty-five (62%) physicians use ≤ 35% as LVEF criteria for ICD referral in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Cardiologists were more familiar than primary care physicians with LVEF criteria for implantation of ICD in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (p value 0.005 and 0.002 respectively). Twenty-nine (27%) participants were unsure regarding benefits of ICDs in eligible women and Blacks. Eighty two (76%) physicians believed that an ICD could benefit patients ≥70 years whereas only 53 (49%) indicated that an ICD would benefit patients ≥ 80 years of age. A lack of familiarity with current clinical guidelines regarding ICD implantation exists. Primary care physicians are less aware of clinical guidelines than are cardiologists. This finding highlights the need to improve the dissemination of guidelines to primary care physicians in an effort to improve ICD utilization.

Subject Index: Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, Physician’s Knowledge, Gender and Racial Disparities

BACKGROUND

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the leading cause of death in developed countries with sudden cardiac death (SCD) accounting for approximately 50% of all cardiovascular deaths.1,2 Patients with significant coronary artery disease (CAD), left ventricular systolic dysfunction and prior ventricular tachy-arrhythmias are at particularly high risk for SCD.3,4 Compared to optimal medical therapy, ICDs have been consistently more efficacious in preventing SCD in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.5–9 The most recent guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 10 recommend the implantation of an ICD for primary prevention of SCD in patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, an LVEF of 35 % or less, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II or Class III heart failure symptoms.

Research has highlighted the under-utilization and inequality in the distribution of ICDs among eligible patients.11–13 Little is known about physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward ICD therapy. Since the recommendation of a physician can greatly influence patient’s decisions regarding ICD implantation, it is critical to gain a better understanding of physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding this life saving technology. The aim of our project was to evaluate knowledge and attitudes of physicians regarding ICD therapy using an original survey instrument. We hypothesized that a lack of knowledge exists among physicians who are involved in the referral of eligible patients for ICD implantation.

METHODS

The survey was developed integrating information from a literature review, the ACC/AHA guidelines regarding ICD therapy, and by consensus of the investigators. To improve the content validity of the survey, the initial draft of the instrument was distributed to a convenience sample of multidisciplinary team of physicians. The critical appraisal of the sample facilitated revision for clarity and reliability. The first items in the instrument assessed self-reported awareness of guidelines as physicians were asked if they were aware of clinical guidelines regarding ICD implantation with a Yes/No question. Their knowledge of the guidelines was further explored by questions regarding LVEF criteria determining ICD eligibility in patients with both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. The following items in the survey were a series of questions to ascertain physicians’ attitudes regarding ICDs, scored on a 5-point Likert scale including if ICDs prolong life, prevent SCD, are beneficial in women, Blacks, and in patients ≥70 and ≥80. We chose this age limit because less published data exists regarding ICDs in the older patient population. Other questions asked were if ICDs are cost-effective and improve quality of life, as well as if any concerns exist regarding manufacturing defects and recalls. In addition to these questions, three clinical scenarios were also included in the survey, which captured physicians’ knowledge regarding appropriate ICD referral criteria. All three scenarios met the ACC/AHA Class I indication for ICD implantation. Finally the survey asked about personal demographics and practice characteristics. Space was provided for physician comments regarding any factors that they perceived as potential barriers for appropriate ICD implantation dissemination. The institutional review board approval was obtained before mailing the survey to physicians.

The original survey instrument was administered by mail to obtain cross-sectional data regarding physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward ICDs. In practice, eligible patients are typically identified by their primary care physician and/or cardiologist and are subsequently referred to an electrophysiologist for the ICD implantation. Thus physicians in the cardiology, general internal medicine, hospitalist and family medicine specialties were chosen for the study. The study was conducted at the University of Rochester Medical Center and the Unity Health System, Rochester NY. This provided representation of both a university and a community based hospital settings. Reminder mailings were sent out three weeks following the initial mailing to non-responders.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the frequency of physicians’ awareness of guidelines, both self reported and objectively by analyzing their knowledge of LVEF criteria. Participant’s demographics and attitudes regarding ICDs were described using frequency analysis. The chi Square χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were used to evaluate the associations between the awareness of guidelines and demographic characteristics as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate factors that may predict ICD referral. We designed three separate models, using the physicians’ responses (Yes/No) to three case scenarios potentially requiring referral for an ICD. The independent variables evaluated in the logistic regression model were physicians knowledge of current guidelines and beliefs regarding the effect of the ICDs in 1) prolonging life, 2) benefits in women 3) benefits in Blacks 4) improve quality of life, 5) cost effective or not, 6) age of physician, 7) gender, 8) years since medical school (<20 or >20 years) and 10) specialty. The barriers for ICD dissemination as reported by study participants were categorized according to the patient level, physician level and system/administrative level.

All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 soft ware. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Respondents and Distribution of Knowledge

Respondent demographics, awareness of clinical guidelines and LVEF cut-off criteria used by the physicians for referral of ICD implantation are shown in Table 1. Seventy-seven (70%) physicians were less than 50 years of age and 57 (52%) graduated from medical school in the last 20 years. Ninety-four (87%) physicians reported that they refer patients to cardiovascular specialists for consideration of an ICD implantation. Eighteen (17%) physicians reported unawareness of the ACC/AHA clinical guidelines for ICD implantation. Eighty-seven (79%) physicians recommended an ICD for “Case A,” of a 45-year-old woman with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and LVEF 30%. Eighty-one (74%) physicians recommended ICD for “Case B” of a 72-year-old man with ischemic cardiomyopathy, LVEF 25%. Fifty-four (50%) physicians recommended an ICD for “Case C” of an 81-year –old man with ischemic cardiomyopathy, LVEF 30–35%.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Awareness of Clinical Guidelines and Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) Cut-off Criteria Used by Physicians for referral of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) implantation.

| Frequency | Percentage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤ 50 | 77 | 70 % | |

| > 50 | 33 | 30 % | ||

| Gender | M | 85 | 78 % | |

| F | 24 | 22 % | ||

| Specialty | Primary Care | 64 | 58 % | |

| Cardiology | 46 | 42 % | ||

| Years Since Medical School Graduation | ≤ 20 | 57 | 52 % | |

| > 20 | 53 | 48 % | ||

| Physicians currently refer patients for ICD | 94 | 87% | ||

| LVEF Cut-off Criteria | ||||

| Ischemic | ≤ 30 % | 45 | 41% | |

| cardiomyopathy | ≤35 % | 64 | 59% | |

| Non-ischemic | ≤ 30 % | 39 | 37% | |

| cardiomyopathy | ≤35 % | 65 | 62% | |

Factors Associated with Physicians Knowledge and Attitudes

Knowledge regarding the current LVEF criterion for ICD implantation in individuals with ischemic cardiomyopathy was significantly higher among cardiologists as compared to primary care physicians (OR 3.1 95% CI 1.3–7.0). A similar association was seen for knowledge of LVEF criteria for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients (OR 3.8 95% CI 1.5–9.4). Physicians younger than 50 years of age were significantly more likely to know the clinical guidelines for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients (OR 3.4 95% CI 1.4–8.2) with no difference in knowledge for LVEF criteria for ischemic cardiomyopathy patients (OR 2.1 95% CI 0.9–4.9). The reported knowledge of current guidelines did not correlate with years from medical school graduation (<20vs>20 years), for ischemic cardiomyopathy, (OR 1.18 95% CI 0.5–2.5) and for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (OR 1.54 95% CI 0.6–3.4). Similarly no associations were found between knowledge and physicians of different gender (OR 0.7 95% CI 0.3–1.9, OR 0.8 95% CI 0.3–2.1) for ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy respectively.

The beliefs and attitudes of physicians regarding ICD therapy are summarized in Table 2. The majority of physicians 94(85%) believe that ICD use prolongs life, and 104(96%) agreed that ICDs can protect from SCD. Twenty-nine (27%) physicians either believe that ICDs have less benefit in women and Blacks or were unsure regarding potential benefits of ICD in these populations. Fifteen (14%) physicians reported concerns regarding manufacturing recalls and defects indicating that such belief could play an important role in referral for ICD implantation. Eighty-two (75%) physicians agreed that an ICD would not improve patients’ quality of life. While 82(76%) physicians reported that ICDs can be beneficial in patients older than 70, only 53(49%) believed that an ICD would be an effective therapy in patients 80 years and older. Sixty-two (59%) physician reported an ICD to be cost effective treatment.

Table 2.

Frequency Distribution of Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) Use:

| Strongly disagree N (%) |

Somewhat disagree N (%) |

Neutral N (%) |

Somewhat agree N (%) |

Strongly agree N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICDs prolong life | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 9 (8) | 38(35) | 56(52) |

| ICDs prevent SCD | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 29(27) | 75(69) |

| Women benefit equally from ICDs compared to men | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | 24(22) | 35(33) | 43(40) |

| Blacks benefit equally from ICDs compared to Whites | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | 24(22) | 33(30) | 46(43) |

| ICDs Improve quality of life | 13(12) | 20(18) | 49(45) | 19(18) | 7 (6) |

| Reported manufacturing defects influence ICD referral | 30(28) | 34(32) | 26(25) | 13(12) | 2 (2) |

| ICDs are Cost-effective | 2 (2) | 13(12) | 29(27) | 40(38) | 22(21) |

| ICDs benefit patients older than 70 years of age | 1 (0.9) | 7 (6) | 18(17) | 45(42) | 37(34) |

| ICDs benefit patients older than 80 years of age | 4 (4) | 19(17) | 32(30) | 41(38) | 12(11) |

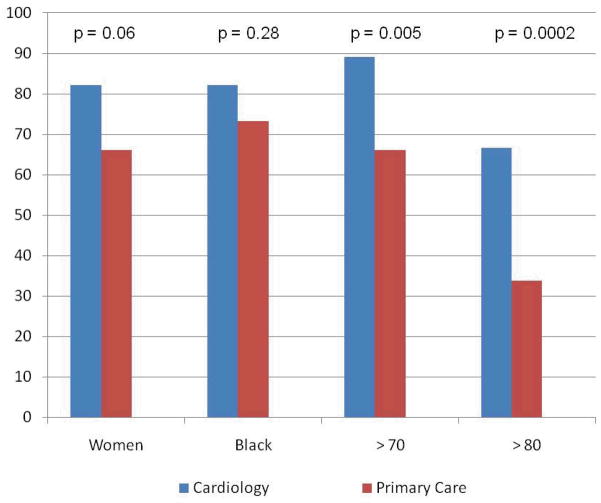

The difference between cardiologist vs. primary care physicians’ attitudes towards an ICD therapy among women, Blacks, patients ≥ 70 and ≥ 80 years of age is shown in Fig I.

Fig I.

Percentage of cardiologist vs primary care who agree that Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator therapy benefits women, Blacks, patients above 70 and above 80 year of age.

Is knowledge of the ACC/AHA guidelines related to ICD referral?

The self reported awareness of ICD clinical guidelines by physicians was significantly associated with ICD referral (OR 8 95% CI 2.4–30). The knowledge of LVEF criteria for non-ischemic cardiomyopathy was not associated with recommendation of ICD for Case A (a patient with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy), (OR 2.1; 95%CI 0.8–5.6). However, the knowledge of LVEF criteria for ischemic cardiomyopathy was significantly associated with recommendation of ICD for Case B and C (patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy), (OR 3.6 95 % CI 1.4–8.8) and (OR 6.1; 95% CI 2.6–14.5) respectively.

Factors Associated with Referral of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators

The variables found to be significantly associated with referral after inclusion in multivariate logistic regression models for the three clinical scenarios are summarized in Table 3. The perception of “cost-effectiveness of ICD” was strongly associated with ICD referral when physicians were presented with Case A. The cardiologists were more likely to recommend this patient for an ICD therapy as compared to primary care physicians. The perception that “ICD benefits patients 70 years and older” was an independent predictor of referral for ICD in Case B. In Case C, physicians younger than 50 years of age were more likely to refer for ICD as compared to physicians > age 50. The perception that “ICD benefits patients 80 and older” was also significantly associated with recommending an ICD for this patient.

TABLE 3.

Logistic Regression of Selected Model Variables on Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) Referral.

| Variable | Odd Ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case A | |||

| Specialty (cardiology vs non-cardiology) | 3.67 | 1.11 – 12.05 | 0.032 |

| ICDs are cost-effective | 2.79 | 1.01 – 7.68 | 0.047 |

| Case B | |||

| ICDs benefit patients older than 70 years of age | 4.00 | 1.52 – 10.49 | 0.004 |

| Case C | |||

| Physician Age (<50 vs >50 years old) | 0.31 | 0.11 – 0.87 | 0.027 |

| ICDs benefit patients older than 80 years of age | 6.49 | 2.57 – 16.40 | 0.0001 |

The reported potential barriers for appropriate ICD utilization as reported by study participants are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Barriers for Dissemination of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators as Reported by the Physicians: Total n = 30.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Function Status | 1 (3) |

| Cognitive function/Dementia | 3 (10) |

| Presence of multiple co-morbidities | 5 (17) |

| Reluctance/preferences | 5 (17) |

| Concerns over device recalls | 1 (3) |

| Age | 1 (3) |

| Compliance | 1 (3) |

| Language barriers | 1 (3) |

| Physicians Characteristics | |

| Lack of familiarity with referral process | 1 (3) |

| Lack of system support for identification of eligible patients | 1 (3) |

| Concerns regarding inappropriate shocks | 2 (7) |

| Concerns regarding cost of devices | 7 (23) |

| Concerns regarding effects on quality of life | 2 (7) |

| System-Based | |

| Insurance | 3 (10) |

DISCUSSION

This study provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the current state of physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding the use of ICDs in their patients. The results show that a majority of physicians surveyed in our sample were aware of the presence of ACC/AHA guidelines for ICD implantation. Knowledge of these guidelines is also associated with reported referral patterns. However, actual knowledge is less robust when physicians are challenged with more detailed questions regarding clinical guidelines, For example, knowledge regarding LVEF criterion for eligibility of patients for an ICD with ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. As expected, cardiologists are more aware of the ICD implantation guidelines than are primary care physicians. However, there was no difference between younger physicians (≤ 50) and those who graduated from medical school within the last 20 years compare to physicians > 50 year of age and physicians graduated from medical school more than 20 years ago in their awareness of the current guidelines. Although the majority of physicians know that ICDs prevent SCD, more than 25% remain unsure regarding benefits of ICDs in women and Blacks. These data suggest that, although many physicians are aware of the current guidelines, their knowledge is insufficient to prompt them to refer all of those individuals who can benefit from this life-saving therapy.

Several potential factors may explain the existing lack of up-to-date knowledge among physicians especially in primary care.14 The busy practice patterns and perception of primary care physicians regarding their role in the referral of devices seem the most important. The primary care physicians provide clinical care for a vast range of clinical issues that go beyond cardiovascular diseases.15 For these busy practitioners, keeping up with the most current clinical research and guidelines seems a daunting task.

In our study, 25% of the physicians were generally unclear regarding the benefits of ICD in women and Blacks. This uncertainty may further contribute to the disparities observed in the use of ICDs. The lack of clear clinical evidence regarding benefits of ICD in these sub-groups of patients may be one of the important factors contributing to these attitudes. In the clinical trials evaluating the benefits of ICDs, the participation of women and racial minorities has traditionally been low compromising the generalizability of results. For example men composed 92% of the individuals in MADIT I, 86% in MUSTT, and 84% in MADIT II.5–7 Although subgroup analyses from some of these studies have shown mixed results on the efficacy of ICD among women as compared to men, the results of these analyses should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size and subsequently limited statistical power.16,17 The literature supporting the benefits of ICD among Blacks also has been mixed. In the sub-study from MADIT II, ICD implantation was associated with reduced total mortality, cardiac death, and SCD in Whites but not in Blacks.18 In the MUSTT trial, Blacks did not benefit from ICD as did Whites.19 In fact Blacks in MUSTT had a better response to anti-arrhythmic medications at EP testing and lower acceptance rate to ICD implantation compared to Whites that led to lower rate of ICD implantation. These issues may have confounded the results showing a lack of benefit in the MUSTT population. In contrast SCD-HeFT trial found an equal reduction in mortality among both racial groups (hazard ratio 0.65 in Blacks and 0.73 in whites).20 The ACC/AHA clinical guidelines recommend ICD use for all eligible patients equally from all racial/ethnic origins who meet the criteria for ICD implantation.

The cost of devices emerged as one of the important factors that physicians perceive as a barrier for the dissemination of ICD and it was also an important predictor of ICD referral. Numerous studies evaluated the cost-effectiveness of ICD use.21,22 The results from these studies are quite varied as the analyses depend on cost estimates, projected follow up care, and make assumption regarding treatment effects. In a cost effectiveness analysis based on the MADIT II population, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was $235,000 per year of life saved, unadjusted for quality of life.21 The cost-effectiveness approached $50,000 to $100, 000 when the data were extrapolated to 12 years. This analysis was limited by the short trial duration and hence the treatment effects in future were estimated. Ideally cost-benefit analyses regarding ICD use should include a person’s remaining years of life. The complexities of cost-effectiveness determinations and resulting controversy and confusion amongst physicians may explain the concerns of physician participants in this study.

The age of the patients, presence of co-morbidities and impact of ICD use on quality of life were other important factors that physicians reported as potential factors that may affect ICD referral. A significantly fewer number of physicians would consider ICD in patients 80 years and older. Although there are no clear “age limits” prescribed in the clinical guidelines ICD is not recommended in patients with severe co-morbidities and expected survival of less than one year. The literature supports the use of ICD in older patients as data has shown that patients 75 and older derive equal benefits for prevention of SCD as compared to younger patients.23 Thus age should be considered in the light of severe co-morbidities, cognitive function and functional status.46 Physicians should communicate with patients and family members regarding potential benefits, risks and alternatives of ICD treatment.

ICDs have no role in improving quality of life, but in previous reports, it has been suggested that ICD therapy may be associated with reduced psychological functioning and reduced quality of life.24,25 In a recently published report from a large primary prevention population, ICD therapy was not associated with any detectable adverse quality of life effects during 30 months of follow up but the ICD shocks were associated with decreased quality of life.26 The results from previous reports on ICD and quality of life may not be applicable to current patients, as significant advances have occurred in the devices and implantation techniques. The currently available devices are much smaller in size and are implanted transvenously as compared to open chest implantation. Further efforts should be focused in designing new ICD algorithms to minimize inappropriate shocks and thus improving the tolerability of devices. Adequate support should be provided to patients who receive ICD shocks to minimize any adverse effects on psychological or physical functioning.

In summary, our project provides a description of the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary care providers and cardiologists regarding the use of ICDs. Since the knowledge of practice guidelines is associated with ICD referral, there may be a need for development of well structured educational programs to improve the referral rates to more appropriate levels based on current evidence. Improving the familiarity of physicians with current guidelines would help incorporate “evidence-based care” in their clinical practice and reduced variability in the delivery of care across different groups of eligible patients.

Our study has a number of limitations. The greatest is a relatively small sample size. The sample does, however represent a diverse group of physicians practicing cardiology and internal medicine affiliated with university and community based hospitals. Moreover these data suggest the need for studies with more substantial study samples in a variety of geographical domains. Some of the other potential limitations of the study include respondent’s recall and response rate. Our study included only three clinical scenarios, so the results may not be applicable to various other clinical situations.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights some of the important factors that may play an influential role in referral of patients for ICD implantation including the cost of devices, area of specialty, age of patients, and of physicians. There is a need not only to improve current knowledge of physicians who may need to refer patients for ICD implantation but also to reduce “grey areas” in the evidence supporting the use of these life saving devices.

References

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2007 Update. A report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–e171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden Cardiac Death in the United States: 1989 to 1999. Circulation. 2001;104:2158–2163. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.098254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zipes DP, Wellens HJ. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1998;98:2334–2351. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lombardi G, Gallagher J, Gennis P. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in New York City: the Pre-Hospital Arrest Survival Evaluation (PHASE) Study. JAMA. 1994;271:678–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Klein H, Levine JH, Saksena S, Waldo AL, Wilber D, Brown MW, Heo M. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary artery disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1933–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1882–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews MLl. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1576–1583. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Greager MA, Ettinger SM, Faxon DP, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2008;117(21):e350–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCUALTIONAHA.108.189742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Al-Khatib SM, Curtis LH, LaBresh KA, Yancy CW, Albert NM, Peterson EDl. Sex and racial differences in the use of implantable Cardioverter-defibrillator among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;298(13):1525–1532. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis LH, Al-Khatib SM, Shea AM, Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Schulman KA. Sex difference in the use of implantable Cardioverter defibrillators for primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death. JAMA. 2007;298(13):1517–1524. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redberg RF. Disparities in use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillatores: Moving beyond process measures to outcomes data. JAMA. 2007;298(13):1564–1566. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stross JK, Harlan WR. The dissemination of new medical information. JAMA. 1979;241:2622–2624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayanian JZ, Hauptman PJ, Guadagnoli E, Antman EM, Pashos CL, McNeil BJ. Knowledge and practices of generalist and specialist physicians regarding drug therapy or acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1136–1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410273311707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zareba W, Moss AJ, Hall J, Wilber DJ, Ruskin JN, Mcnitt S, Brown M, Wang H. Clinical course and Implantable Cardioverter defibrillator therapy in postinfarction women with severe left ventricular dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16(12):1265–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo AM, Poole JE, Mark DB, Anderson J, Hellkamp AS, Lee KL, Johnson GW, Domanski M, Bardy GH. Primary prevention with defibrillator therapy in women: Results from the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(7):720–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vorobiof G, Goldenberg I, Moss A, Zareba W, McNitt S. Effectiveness of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator in Blacks versus Whites. American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;98(10):1383–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo AM, Hafley GE, Lee KL, Stamato NJ, Lehmann MH, Page RL, Kus T, Buxton AE. Racial Differences in Outcome in the Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT): A comparison of Whites versus Blacks. Circulation. 2003;108:67–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078640.59296.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell JE, Hellkamp AS, Mark DB, Anderson J, Poole JE, Lee KL, Brady GH. Outcome in African American and Other Minorities in the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Am Heart J. 2008;155(3):501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders GD, Hlatky MA, Every NR, McDonald KM, Heidenreich PA, Parsons LS, Owens DK. Potential cost-effectiveness of prophylactic use of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator or amiodarone after myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:870–883. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-10-200111200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zwanziger J, Hall WJ, Dick AW, Zhao H, Mushlin AI, Hahn RM, Wang H, Andrews ML, Mooney C, Wang H, Moss AJ. The cost-effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Results from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT)-II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2310–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang DT, Sesselberg HW, Mcnitt S, Noyes K, Andrews ML, Hall WJ, Dick A, Daubert JP, Zareba W, Moss AJ. Improved survival associated with prophylactic implantable defibrillators in elderly patients with prior myocardial infarction and depressed ventricular function: A MADIT II Substudy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18(8):833–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myerburg RJ. Implantable Cardioverter defibrillators after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2245–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0803409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irvine J, Dorian P, Baker B, O’Brien BJ, Roberts R, Gent M, Newman D, Connolly SJ. Quality of life in the Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study (CIDS) Am Heart J. 2002;144:282–289. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.124049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mark DB, Anstrom KJ, Sun JL, Clapp-Channing NE, Tsiatis AA, Davidson-Ray L, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Quality of life with defibrillator therapy or amiodarone in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:999–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]