Summary

Recent studies have demonstrated alterations in the cortisol awakening response (CAR) and brain abnormalities in adults with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). While adolescents with T2DM exhibit similar brain abnormalities, less is known about whether brain impairments and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis abnormalities are already present in adolescents with pre-diabetic conditions such as insulin resistance (IR). This study included 33 adolescents with IR and 20 without IR. Adolescents with IR had a blunted CAR, smaller hippocampal volumes, and greater frontal lobe atrophy compared to controls. Mediation analyses indicated pathways whereby a smaller CAR was associated with higher BMI which was in turn associated with fasting insulin levels, which in turn was related to smaller hippocampal volume and greater frontal lobe atrophy. While we had hypothesized that HPA dysregulation may result from brain abnormalities, our findings suggest that HPA dysregulation may also impact brain structures through associations with metabolic abnormalities.

Keywords: Adolescence, CAR, Obesity, Hippocampus, Frontal Lobes, Cortisol

1. Introduction

The current obesity epidemic has led to the proliferation of a large population of insulin resistant adolescents (Sinha et al., 2002). Cortisol, a steroid hormone that plays a crucial role in glucose regulation as well as homeostatic responses to stressors such as obesity, is of particular importance for those with insulin resistance (Bjorntorp and Rosmond, 2000). Cortisol levels vary throughout the day according to a fairly standard diurnal profile, necessitating the consideration of when, and under what conditions, cortisol levels should be collected. The cortisol awakening response (CAR) consists of a 50–75% increase in salivary free cortisol levels that occurs approximately 30 minutes after waking up in the morning (Clow et al., 2004). The CAR has gained attention as a good indicator of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis integrity because of its ease of collection, intra-individual stability, and sensitivity to subtle changes in the axis (Wüst et al., 2000).

Studies examining the link between obesity and insulin resistance to CAR have produced mixed findings. In a study of young and middle age adult men and women (23–51 years of age), Therrien et al. (2007) found that obese men had a higher CAR than did lean men, while the CAR did not differ between obese and lean women. In contrast to these findings, higher BMI was unrelated to the CAR in a study involving 3956 men and women aged 50–74 years old (Kumari et al., 2010). Another study, however, found that obese women aged 15–44 had a blunted CAR (Ranjit et al., 2005). Higher fasting insulin levels have also been shown to be related to a lower CAR in middle aged and elderly adults (Bruehl et al., 2009a). Although no studies have yet examined whether adolescents with obesity or insulin resistance exhibit altered CARs, there is some evidence for alteration of the HPA axis in obese children. Compared to children without insulin resistance and lean children, serum cortisol levels are elevated in pre-pubertal children with obesity and pubertal children with insulin resistance (Reinehr and Andler, 2004). Higher baseline cortisol levels in 8 to 13 year old Latino youth have also been shown to be predictive of decreased insulin sensitivity over a one year period (Adam et al., 2010).

Causal relations between HPA axis dysregulation and diabetes associated factors are still not well understood (Bjorntorp and Rosmond, 2000). According to the “peripheral hypothesis”, cortisol production is altered as a consequence of obesity. Meanwhile, in the “central hypothesis”, dysregulation of central systems (such as abnormalities in HPA axis feedback control) is considered the cause of obesity. While we have chosen to focus on the cortisol component of the HPA axis, other researchers have demonstrated that disruption of circadian cycles, which emanate predominantly from the hypothalamus, can impact metabolic processes (Huang et al., 2011). Consistent with the “central hypothesis”, animal models have also shown that genetically induced perturbations to the hypothalamic based circadian cycle resulted in obesity (Ando et al., 2011). The “central hypothesis” was further bolstered by recent research providing evidence that prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids induces alterations in the HPA axis and that these alterations may mediate the development of obesity and T2DM later in life (Reynolds, 2010). While these issues have yet to be conclusively settled, overall evidence seems to support the “central hypothesis” (Bjorntorp and Rosmond, 2000). Based on the “central hypothesis” model, HPA axis dysregulation would be related to obesity and insulin resistance in both adults and adolescents (Bjorntorp, et al., 1999).

Alterations in the CAR may be linked to hippocampal and frontal volume changes as the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors targeted by cortisol are concentrated in those brain areas (Hinkelmann, 2009). Medial temporal lobe and frontal regions play an inhibitory role in the regulation of the HPA axis through negative feedback, and thus have been hypothesized to be specifically related to the CAR (Fries et al., 2009; Clow et al., 2010). Patients with hippocampal lesions exhibit a blunted CAR (Buchanan et al., 2004) and among those without lesions, a smaller hippocampal volume has also been associated with a smaller CAR (Pruessner et al., 2007). Evidence for direct associations between the CAR and frontal lobe functioning is more limited (Fries et al., 2009). However, one study has demonstrated a smaller CAR in patients who had damage to the frontal and temporal lobes (Wolf et al., 2005). Evidence is scant when looking at these associations in adolescents. A study of healthy pre-pubertal children found no relation between serum cortisol levels and hippocampal volumes, but did find a relationship between serum cortisol and regional variations in hippocampal surface morphology (inward or outward deformations of the hippocampus relative to a reference hippocampus), such that outward deformations of the anterior segment and inward deformations of lateral aspects of the medial segment were related to higher cortisol levels (Wiedenmayer et al., 2006). These associations have yet to be studied in an adolescent population.

Given that the hippocampii (and possibly the frontal lobes) play a role in regulating the CAR, we hypothesize that changes in the CAR may conversely also exert an effect on hippocampal and frontal lobe volumes. Based on our interpretation of previous literature we hypothesized that there is a relation between CAR and hippocampal and frontal lobe volumes mediated by the development of obesity and increases in fasting insulin. The reasoning behind this hypothesis is as follows: according to the central hypothesis described above, HPA axis dysregulation, detected by blunting of the CAR, may lead to the development of obesity and subsequent insulin resistance (Bjorntorp and Rosmond, 2000). Meanwhile, both obesity and T2DM (the combination of a severe insulin resistance and beta cell failure) have been associated with smaller hippocampal and frontal lobe volumes in adults (Bruehl et al., 2009a; Bruehl et al., 2009b; Raji et al., 2010). Adolescents with T2DM, when compared with matched obese adolescents without insulin resistance, show both hippocampal and frontal lobe volume reductions (Bruehl et al., 2011), which adds some support for our hypothesis that fasting insulin levels may mediate volume reductions in the brain. While this hypothesis has not been tested directly, some preliminary support comes from findings that adults with insulin resistance exhibit cognitive deficits that are similar to those associated with T2DM (Bruehl et al., 2010). Thus, the purpose of this study was first to examine whether obesity and insulin resistance in adolescents were associated with alterations in the CAR, hippocampus, and frontal lobes, and then to use mediation models to examine whether BMI and elevated fasting insulin levels mediated the relationships between CAR and hippocampal or frontal lobe volumes.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Fifty three adolescent volunteers (33 with insulin resistance, and 20 controls without insulin resistance) participated in the study. Participants were recruited through internet advertisements and through a related study of diabetes prevention that targeted obese adolescents in NYC public schools. Participants came to the laboratory for an evaluation that included medical evaluation and an MRI scan. We excluded adolescents for participation if they had significant medical conditions (other than polycystic ovary disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or T2DM), sexual development tanner stage < 4, BMI > 50 (as they would not fit in the MRI scanner), pregnancy, major psychiatric illness (including substance abuse), taking any prescribed psychoactive medication), and mental retardation or significant learning disability. Participants with T2DM, were however, excluded from this analysis. Saliva samples were collected by each participant at home. The study was approved by the local institutional board of research associates. All participants gave informed written assent and informed written consent was provided by participants if older than 18 years of age or their parents for those younger than 18. Descriptive statistics for each group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by group: Mean (SD).

| Control group (n = 20) | Insulin Resistant (n = 33) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 18.11 (1.86) | 17.51 (1.78) |

| Gender (F/M) | 12/8 | 20/13 |

| Education (in years) | 11.85 (1.90) | 11.64 (2.07) |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25.49 (6.04) | 34.74 (7.51) |

| Fasting Insulin level (μIU/mL) * | 5.28 (1.95) | 21.02 (13.78) |

| Average Wake up Time | 7:25 (47 mins) | 7:21 (36 mins) |

p < .001

2.2. Definition of Insulin Resistance

Determination of insulin resistance was made based on the fasting glucose and insulin levels using the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI = 1/(Log10(fasting insulin) + Log10(fasting glucose))) (Katz et al., 2002). Participants with a QUICKI score ≤ 0.35 were classified as insulin resistant. Those with a score > 0.35 were classified as not insulin resistant.

2.3. Cortisol Assessment

Participants were given Salivette sampling devices (Salivette, Sarstedt, Nuembrecht, Germany) and received instructions on how to collect saliva samples at home. Moreover, participants received a printout with written instructions. They were instructed to collect samples at wake-up, 15, 30, and 60 min post-wake-up and then at 1100h, 1500h, and 2000h. The instruction sheet also contained a table on which they were asked to indicate the exact times at which they collected saliva as well as their wake-up time. This table allowed us to monitor whether participants followed the indicated schedule. Furthermore, the verbal and written instructions indicated that participants should refrain from eating, drinking, or putting anything in their mouths until after collecting the 60 minute post-wake-up sample. Moreover, they were asked not to eat, drink, smoke, or brush teeth for at least 30 minutes before each collection. Participants kept the Salivettes in the freezer before bringing them to the laboratory on their next visit. At the laboratory they were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

2.4. Assays

Insulin was measured using our certified hospital clinical laboratory. Free salivary cortisol was analyzed by chemi-luminescence assay (CLIA) with a sensitivity of .25 nmol/l (IBL, Hamburg, Germany). These assays were used to calculate the cortisol awakening response, the physiologically normal increase in cortisol seen shortly after waking. To allow for individual differences in the timing of the cortisol awakening response, we first examined each individual’s cortisol levels at 15, 30, and 60 minutes post awakening to determine their peak level. We then subtracted the level at awakening from this peak level. Thus, the CAR was calculated by measuring the maximum difference between the wake-up cortisol value (0 mins) and the morning cortisol values (15, 30, or 60 mins) (Pruessner, Wolf, et al., 1997).

2.5. Neuroimaging

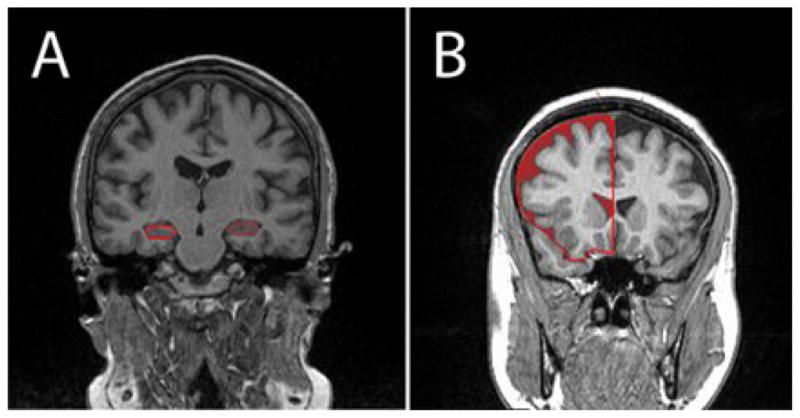

Adolescents were scanned using a 1.5-T Siemens Avanto MRI system. Structural images were acquired using a T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo acquisition (TR 1300 ms; TE 4.38 ms; TI 800ms; FOV 250 × 250; 196 slices; slice thickness 1.2mm; NEX 1; Flip angle 15°). Signal-intensity-normalized coronal images were used to manually draw regions of interest (ROIs) including hippocampus, superior-temporal-gyrus, and frontal lobe as seen in Figure 1. Intracranial vault (ICV) volume was drawn on sagittal images. Our parcellation methods have been shown to be highly reliable (Convit et al., 1997, 1999, 2001) and more details on the methods can be found in Gold et al. (2007). Atrophy in the frontal lobe was determined using a threshold procedure to determine the volume of CSF in the frontal lobe. ROIs were drawn blind to group membership or participant identity. Brain volumes were residualized to the intracranial vault volume in order to control for differences in head size.

Figure 1.

1.5-T MRI Coronal images with regions of interest (ROI) outlined for volumetric analysis of A) hippocampus and B) frontal lobe CSF.

2.6. Statistical analyses

The distributions of all variables were first inspected. Frontal lobe atrophy and insulin were highly positively skewed, and thus a natural log transformation was applied to each variable to normalize the distributions. BMI was missing for one subject, thus analyses using BMI have a sample size of 52. Cortisol levels at afternoon time points were also missing for 6 participants and thus between group differences on diurnal decline are based on a sample size of 47.

Independent samples t-tests and Chi-squared tests were used to determine whether groups differed on demographic or medical characteristics and to examine group differences in the CAR and brain volumes.

Pearson’s correlations were used to first establish associations among variables. Based on these findings, mediation analyses were then conducted using MED3C in SPSS (Hayes et al., 2010) in order to further examine pathways of relations between the CAR, BMI, fasting insulin levels, and brain volumes. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 18.

3. Results

3.1. Medical and Demographic Characteristics

Groups did not differ on demographic characteristics including SES, ethnicity, age, or gender. As expected, insulin resistant participants had higher fasting insulin levels, and higher BMI than controls (all p < .001).

3.2. Salivary Cortisol: Diurnal Profile and CAR

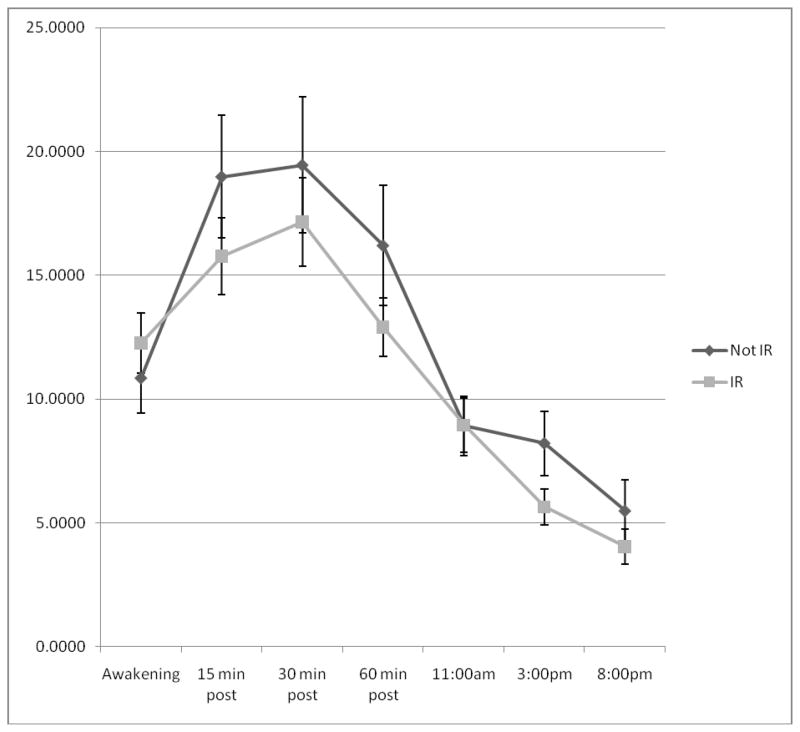

Independent samples t-tests indicated that there were no between group differences in awakening cortisol levels; t(51) = −.75, p = .46, nor were there differences in afternoon diurnal decline from 1100h to 2000h; t(50) = −.73, p = .47. As shown in Figure 2, however, adolescents with IR tended to have lower afternoon cortisol levels than adolescents without IR.

Figure 2.

Cortisol profiles of adolescents with and without IR.

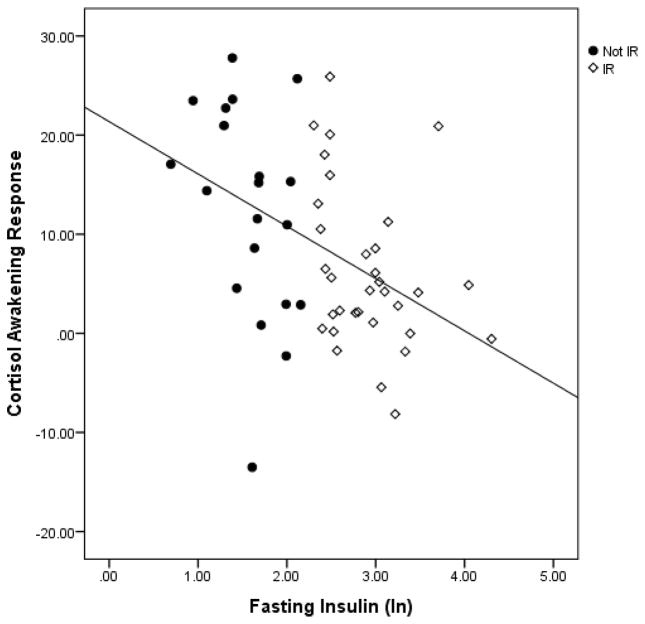

Participants with insulin resistance had a smaller cortisol awakening response than control participants; t(51) = 2.35, p = .02. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, in the sample as a whole, CAR was also significantly correlated with fasting insulin levels (r = −.44, p =.001). This relation remained significant when controlling for age, gender, and wake up time (r= −.45, p =.001).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot indicating the relationship between fasting insulin levels and CAR.

3.3. Brain Volumes

Independent samples t-tests indicated that participants with insulin resistance had smaller ICV-adjusted hippocampal volumes, t(51) = 3.46, p = .001, and greater ICV-adjusted atrophy in the frontal lobe, t(51) = −2.65, p = .01. The superior temporal gyrus served as a control region and as expected, there were no between group differences, t(51) = .83, p = .41. In the sample as a whole, higher insulin levels were associated with smaller ICV-adjusted hippocampal volumes (r = −.39, p = .004) and greater ICV-adjusted frontal lobe atrophy (r =.46, p < .001).

3.4. Associations between CAR and Brain Volumes

CAR significantly correlated with both ICV-adjusted hippocampal volume (r = .30, p = .03) and with ICV-adjusted frontal lobe atrophy (r = −.32, p = .02). To test our hypothesis that BMI and fasting insulin levels would mediate relations between the CAR and brain volumes, we next tested two multiple step mediation models in which CAR predicted BMI, which in turn predicted insulin, which in turn predicted the volume of the hippocampus and frontal lobe atrophy (in separate models). Analyses were conducted using MED3C in SPSS (Hayes et al., 2010) and controlled for age, gender, and wakeup time Findings indicated that the indirect effects of CAR on both the volume of the hippocampus and frontal lobe atrophy through BMI and insulin were significant (Hippocampus, CI: .001, .02; Frontal lobe atrophy, CI: −.02, −.003).

4. Discussion

Overall, we found that adolescents with insulin resistance exhibited a blunted CAR and had smaller hippocampal volumes and greater frontal lobe atrophy than did demographically-matched non-insulin resistant adolescents. These results extend prior findings of relations between insulin resistance and HPA axis alterations in children, which have mainly relied on single time point measures of serum cortisol (Reinehr and Andler, 2004; Adam et al., 2010). We also found some evidence that adolescents with IR had no difference in afternoon diurnal cortisol slopes but may exhibit lower levels of cortisol throughout the day, which is consistent with results indicating that when compared with lean women, obese women had lower cortisol levels in the afternoon although they had no difference in the afternoon slope of decline (Ranjit, et al., 2005). Moreover, our findings demonstrate that adolescents with insulin resistance exhibit HPA axis alterations prior to developing diabetes, indicating that disruptions in the HPA axis may be present in pre-clinical forms of marked insulin resistance prior to the development of the diabetic phenotype.

We also found support for two parallel mediation models in which the relationships between the CAR and hippocampal volume and frontal lobe atrophy, were mediated by BMI and fasting insulin levels. The first pathway of this model, in which higher BMI was related to a smaller CAR, is consistent with findings of Kumari et al. (2010). While our analyses do not allow us to confirm any causal direction, a model in which a blunted CAR predicts increased BMI, which then leads to increases in fasting insulin levels, is consistent with the “central hypothesis”, which posits that dysregulation of the HPA axis is a cause rather than an outcome of obesity and insulin resistance (Bjorntorp, et al., 1999; Bjorntorp & Rosmond, 2000). Furthermore, our results suggest that fasting insulin levels, which indicate insulin resistance when elevated, may play a role in the pathway by which obesity affects the brain. While, the underlying mechanisms of this pathway are not yet known (Bruehl et al., 2011 – pg 6 for one possible explanation), a causal role for insulin resistance is further suggested both by evidence that adults with type 1 diabetes (which is not preceded by insulin resistance) do not have hippocampal reductions (Lobnig et al., 2006) and by evidence that adults with insulin resistance exhibit cognitive deficits that are similar to those of adults with T2DM (Bruehl et al., 2010).

Although these mediation models suggest a particular progression, we cannot make any causal claims, and it is likely that these processes are related cyclically. While disruptions in central regulatory systems may in turn lead to obesity, to subsequent insulin resistance, and then to brain alterations, these brain alterations may lead to further dysregulation of the HPA axis. The hippocampus and frontal lobes have been demonstrated to play an important role in the inhibitory feedback loop regulating the HPA axis, as these regions contain high concentrations of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors (Hinkelmann, 2009). Thus, alterations in these areas may lead to poorer inhibition of the HPA axis and thus to higher cortisol levels, which would be consistent with the higher serum cortisol levels that have been found in insulin resistant children (Reinehr and Andler, 2004; Adam et al., 2010). These regions have also been specifically hypothesized to regulate the CAR (Fries et al., 2009; Clow et al., 2010) as hippocampal lesions (Buchanan et al., 2004) and smaller hippocampal volumes in healthy participants (Pruessner et al., 2007) have been associated with a smaller CAR. Thus it is possible that relations between the CAR and hippocampal volumes, as well as relations between the CAR and frontal lobe atrophy, are bidirectional.

As noted throughout the discussion, this study is limited in its ability to make causal claims, and thus a smaller hippocampus or greater frontal lobe atrophy may have been the cause rather than the outcome. Further longitudinal work is necessary to demonstrate causal relations in the mediation pathways presented. In addition, our relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of these results. Furthermore, there may be problems related to the salivary samples themselves since study participants were responsible for recording the time of collection of their own samples, and adolescents are often not as reliable as adults. We mitigated this issue by looking for the maximum cortisol response among three early morning time points, limiting the importance of the participant’s recorded collection time. The collection of samples on only one day was not ideal – collecting samples over multiple days has been shown to allow for a more stable estimate of the CAR and comparing cortisol levels across at least two days can help to determine whether or not participants complied with the saliva collection protocol (Clow, et al., 2004). Moreover, having additional reminders such as text messages or alarms might help in assessing whether adolescents complied with the saliva collection schedule.

In conclusion, we find a blunted CAR, smaller hippocampal volume, and greater frontal lobe atrophy in adolescents with insulin resistance. Moreover, we find some support for a mediation model in which blunting of the CAR is associated with higher BMI, which in turn predicts higher fasting insulin levels, which in turn is associated with brain abnormalities. Thus, our results suggest that HPA dysregulation is not only a result of brain abnormalities, but may also play a role in metabolic alterations that in turn may cause brain abnormalities.

Table 2.

Brain volumes in cm3 (average of left- and right- hemispheres; mean (SD)).

| Brain Volumes (cm3) | Control group (n= 20) | Insulin Resistant (n = 33) |

|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus* | 5.85 (.63) | 5.35 (.61) |

| Superior temporal gyrus | 47.42 (4.62) | 46.50 (5.60) |

| Frontal lobe atrophy* | 8.08 (3.30) | 12.90 (6.40) |

| ICV | 1177.33 (92.35) | 1188.11 (105.05) |

p < .01

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health DK 083537 and, supported in part by grant 1UL1RR029893 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Role of Funding Source

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health DK 083537 and, supported in part by grant 1UL1RR029893 from the National Center for Research Resources. The funding sources had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Antonio Convit designed the study, wrote the protocol, and was involved in preparation of the manuscript. Will Wedin conducted literature searches and aided in preparation of the manuscript. Aziz Tirsi under the supervision of Antonio Convit conducted the brain volume measurements and aided in the statistical analyses and interpretation of the data. Alexandra Ursache conducted the statistical analyses, interacting with Antonio Convit constructed the conceptual arguments in the interpretation of the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam TC, Hasson RE, Ventura EE, Toledo-Corral C, Le K, Mahurkar S, Lane CJ, Weigensberg MJ, Goran MI. Cortisol is negatively associated with insulin sensitivity in overweight Latino youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4729–4735. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H, Kumazaki M, Motosugi Y, Ushijima K, Maekawa T, Ishikawa E, Fujimua A. Impairment of peripheral circadian clocks precedes metabolic abnormalities in ob/ob mice. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1347–1354. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp P, Holm G, Rosmond R. Hypothalamic arousal, insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 1999;16:373–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björntorp P, Rosmond R. Obesity and cortisol. Nutrition. 2000;16:924–936. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl H, Sweat V, Hassenstab J, Polyakov V, Convit A. Cognitive impairment in nondiabetic middle-aged and older adults is associated with insulin resistance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32:487–493. doi: 10.1080/13803390903224928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl H, Sweat V, Tirsi A, Sha B, Convit A. Obese adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus have hippocampal and frontal lobe volume reductions. Neurosci Med. 2011;2:34–42. doi: 10.4236/nm.2011.21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl H, Wolf OT, Convit A. A blunted cortisol awakening response and hippocampal atrophy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009a;34:815–821. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl H, Wolf OT, Sweat V, Tirsi A, Richardson S, Convit A. Modifiers of cognitive function and brain structure in middle-aged and elderly individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Brain Research. 2009b;1280:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TW, Kern S, Allen JS, Tranel D, Kirschbaum C. Circadian regulation of cortisol after hippocampal damage in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clow A, Thorn L, Evans P, Hucklebridge F. The awakening cortisol response: methodological issues and significance. Stress. 2004;7:29–37. doi: 10.1080/10253890410001667205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clow A, Hucklebridge F, Stalder T, Evans P, Thorn L. The cortisol awakening response: More than a measure of HPA axis function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit A, de Leon MJ, Tarshish C, De Santi S, Tsui W, Rusinek H, George AE. Specific hippocampal volume reductions in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit A, McHugh PR, Wolf OT, de Leon MJ, Bobinski M, DeSanti S, Roche A, Tsui W. MRI volume of the amygdala: a reliable method allowing separation from the hippocampal formation. Psychiatry Res Neuroimag. 1999;90:113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit A, Wolf OT, de Leon MJ, Patalinjug M, Kandil E, Cardebat D, Scherer A, Saint Louis LA, Cancro R. Volumetric analysis of the pre-frontal regions: findings in aging and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimag. 2001;107:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay F, Khan A, Cintra A, Davani B, Ling ZC, Andersson A, Ostenson CG, Gustafsson J, Efendic S, Okret S. Pancreatic beta cells are important targets for the diabetogenic effects of glucocorticoids. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2094–2098. doi: 10.1172/JCI119743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries E, Dettenborn L, Kirschbaum C. The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. Int J Psychophysiol. 2009;72:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SM, Dziobek I, Sweat V, Tirsi A, Rogers K, Bruehl H, Tsui W, Richardson S, Javier E, Convit A. Hippocampal damage and memory impairments as possible early brain complications of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:711–719. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ, Myers TA. Mediation and the estimation of indirect effects in political communication research. In: Bucy EP, Holbert RL, editors. Sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures, and analytical techniques. Routledge; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkelmann K, Moritz S, Botzenhardt J, Riedesel K, Wiedemann K, Kellner M, Otte C. Cognitive impairment in major depression: Association with salivary cortisol. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Ramsey KM, Marcheva B, Bass J. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2133–2141. doi: 10.1172/JCI46043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron AD, Follmann DA, Sullivan G, Quon MJ. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2402–2410. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M, Chandola T, Brunner E, Kivimaki M. A nonlinear relationship of generalized and central obesity with diurnal cortisol secretion in the Whitehall II study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4415–4423. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobnig BM, Kroemeke O, Optenhostert-Porst C, Wolf OT. Hippocampal volume and cognitive performance in long-standing type 1 diabetic patients without macrovascular complications. Diabetic Medicine. 2006;23:32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Wolf OT, Hellhammer DH, Buske-Kirschbaum A, von Auer K, Jobst S, Kaspers F, Kirschbaum C. Free cortisol levels after awakening: A reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sciences. 1997;61:2539–2549. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner M, Pruessner JC, Hellhammer DH, Pike GB, Lupien SJ. The associations among hippocampal volume, cortisol reactivity, and memory performance in healthy young men. Psychiatry Res. 2007;155:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji CA, Ho AJ, Parikshak N, Becker JT, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Hua X, Leow AD, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Brain structure and obesity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:353–364. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit N, Young EA, Raghunathan TE, Kaplan GA. Modeling cortisol rhythms in a population-based study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinehr T, Andler W. Cortisol and its relation to insulin resistance before and after weight loss in obese children. Horm Res. 2004;62:107–112. doi: 10.1159/000079841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RM. Corticosteroid-mediated programming and the pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;122:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B, Tamborlane WV, Banyas B, Allen K, Savoye M, Rieger V, Taksali S, Barbetta G, Sherwin RS, Caprio S. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance among children and adolescents with marked obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:802–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therrien F, Drapeau V, Lalonde J, Lupien SJ, Beaulieu S, Tremplay A, Richard D. Awakening cortisol response in lean, obese, and reduced obese individuals: effect of gender and fat distribution. Obesity. 2007;15:377–385. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenmayer CP, Bansal R, Anderson GM, Zhu H, Amat J, Whiteman R, Peterson BS. Cortisol levels and hippocampus volumes in healthy preadolescent children. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:856–861. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf OT, Fujiwara E, Luwinski G, Kirschbaum C, Markowitsch HJ. No morning cortisol response in patients with severe global amnesia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüst S, Federenko I, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress, and the free cortisol response to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:707–720. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]