Abstract

Introduction

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) is the second most frequent metabolic bone disease with the spine being a common site of manifestation. Still, neither the disease’s etiology nor reasons for its manifestation at preferred skeletal sites are understood. The aim of the current study was therefore to perform a histologic and histomorphometric analysis of PBD biopsies of the spine to achieve a more detailed understanding concerning PDB activity and characteristics.

Materials and methods

Out of 754 cases with histologically proven PDB, 101 cases were identified to have involvement of the spine. A total of 29 individual vertebral body biopsies were available for histologic and histomorphometric analysis and were compared to age- and sex-matched spinal bone specimens obtained from skeletal-intact individuals at autopsy. Histomorphometric results were correlated with vertebral body height, disease location and iliac crest biopsies.

Results

In the majority of patients, PDB was located in the lumbar spine (62.2%). The cervical spine was affected in 8.2% of all cases with involvement of the second vertebral body (C2) in every other case. In comparison to age-matched individuals, histomorphometric analysis of vertebral body biopsies revealed a significant increase both in trabecular bone volume as well as osteoid parameters. In comparison to histomorphometric data obtained for extra-spinal skeletal locations affected by PDB (iliac crest), no differences in bone micro-architecture or disease activity were observed.

Conclusion

Disease activity in terms of osteoblast and osteoclast number does not appear to be significantly associated with disease location when spinal and iliac bone biopsies are compared. However, a positive correlation between vertebral body height and density in skeletal-intact individuals and disease incidence was observed leading to the conclusion that vertebral body height and possibly at least the spine bone volume together with bone density might play an important role in the incidence of PDB.

Keywords: PDB (Paget disease of bone), Spine, Histology, Histomorphometry, Osteoclasts

Introduction

The spine has been reported to be the second most commonly affected site in Paget disease of bone (PDB), a chronic metabolically active bone disease [1–7]. Monostotic pagetic involvement of the spine is rarely described, and polyostotic cases are more common [8]. Still, it can be challenging to detect all sites affected by PDB with the help of conventional X-ray alone. Therefore, in order to differentiate between monostotic and polyostotic disease manifestations, scintigraphic bone scans (99mTc-bisphosphonate) are routinely used. In those cases where the patient’s clinical presentation, typical elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase (sALP) or radiological imaging does not lead to a definite diagnosis, invasive diagnostic techniques such as needle biopsies might become necessary.

A previous study performed by our group reported on 754 cases with histologically proven PDB [1]. Histological samples obtained from the iliac crest were analyzed with the help of histomorphometry and the results were noteworthy. A total of 101 patients (13.4%) presented with spinal involvement of the disease. Due to the lack of histological data on PDB of the spine, we therefore performed histological and histomorphometric analyses of vertebral body biopsies available from the cohort’s patients with spinal PDB manifestation.

This study’s aim was therefore to present the first histological evaluation of a series of vertebral body biopsies from a large cohort of patients with monostotic and polyostotic spinal PDB manifestation. Consequently, our goal was to achieve a better understanding of the disease’s activity in different spinal locations and in comparison to extra-spinal locations like the iliac crest.

Materials and methods

Epidemiological data of PDB samples and control specimens

The files of the Hamburg Bone Register at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf were searched for cases diagnosed as PDB. Here, biopsies of a total of 754 PDB cases were collected between January 1972 and March 2010. Iliac crest biopsies were performed in all patients to characterize skeletal and bone turnover status at tissue level in general or to prove polyostotic involvement of PDB in particular.

Out of the 754 cases reviewed by Seitz et al. [1], 101 cases presented with monostotic or polyostotic involvement of the spine. Those were reviewed in a retrospective study between January 1972 and March 2010. Seventy-two of these cases were obtained from consultatory work, whereas 29 cases were obtained at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. Details of all patients, including patient history, treatment course and clinical complications, were recorded; sALP levels were determined in units per liter (U/L) at the time of diagnosis. Characteristic histopathologic features were compared with radiologic findings for each patient. A total of 29 spinal PDB cases (4 cervical spine, 4 thoracic spine, 21 lumbar spine) were available for histological and histomorphometric analysis. In those cases, a vertebral body biopsy—in addition to an iliac crest bone biopsy—was performed to confirm the diagnosis of a spinal manifestation of Paget disease. In cases with histopathologically proven PDB of the pelvis (i.e., polyostotic paget), where based on clinical and radiological findings spinal disease manifestation was certain, no spinal biopsies were available.

Moreover, 29 autopsy cases served as controls for PDB biopsies. The complete spinal column was harvested from those skeletal-intact individuals with no recorded bone disease within the first 48 h post-mortem (16 male; 13 female). Matched-pair block specimens were extracted and served as control samples. This study was carried out according to existing rules and regulations of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. All patients died in accidents or of acute disease. Review of hospital records and whole body autopsy reports were used to exclude individuals with cancer, diabetes, glucocorticoid medication or donors on other drugs known to affect calcium metabolism. Therefore, patients with severe liver or kidney disease or periods of longer immobilization were excluded. Iliac crest biopsies were obtained from all autopsy cases to furthermore exclude general and metabolic skeletal diseases. These specimens served as reference values for PDB specimens.

Undecalcified histology of PDB biopsies and control specimens

All 29 PDB biopsies were evaluated for histological confirmation of the diagnosis. Biopsies of similar size were extracted from the block specimens of skeletal-intact autopsy control specimens. PDB and control biopsies were embedded undecalcified in methylmethacrylate and cut into sections of 4-μm thickness using a k-microtome (Jung, Heidelberg, Germany). Histological evaluation of all specimens was made following standard staining procedures as described before [9].

Quantitative static histomorphometry

Parameters of static histomorphometry were quantified on von Kossa/van Giesson- or Toluidine blue-stained undecalcified sections of vertebral body specimens from 29 patients with manifestation of PDB of the spine and set in direct comparison to 29 autopsy block obtained from skeletal-intact donors. Analyses of bone volume per tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), osteoid volume (OV/BV), osteoid surface (OS/BS) and fibrous tissue (FbI/Pm), as well as the determination of osteoblast (NOb/BPm) and osteoclast numbers (NOc/BPm) and surface indices (ObS/BS and OcS/BS), were carried out according to the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) standards [10] using the Osteomeasure histomorphometry system (Osteometrics, Atlanta, GA, USA) connected to a Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), both for PDB and control cases.

The data obtained here were compared to and correlated with histomorphometric findings of iliac crest bone biopsies with clinically and histologically proven PDB. A detailed description of these iliac crest biopsies can be found in the publication described above by Seitz et al.

Radiologic documentation of control samples and measurement of vertebral body heights

Vertebral bodies of all 29 control samples were dissected at autopsy, contact X-ray images were taken (Faxitron X-ray LLC, Lincolnshire, IL, USA) and vertebral body heights were measured morphometrically (ImageJ, Sun Microsystems Inc. N.I.H., USA) prior to histologic preparation. Histologic preparation was performed as described above.

Radiologic assessment of PBD of the spine

Conventional X-ray images that had been taken while establishing the PDB diagnosis were available for the majority of patients, but was not performed systematically. In selected cases, images documenting the disease’s course were available.

Statistical analysis

For statistical evaluation, two tailed Student’s t test was performed to reveal differences between control and PDB groups using the software SPSS Version 17.0. For all tests, p values <0.05 were considered as “statistically significant”, while p values <0.01 were considered as “strongly significant”. Pearson’s correlation was used for correlation coefficient and a p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic data

In our cohort of 754 patients, 101 cases involving the spine (13.4%) were recorded. The majority of cases were found in male patients (60.4%), whereas 39.6% were female. A total of 62 patients (61.4%) presented with polyostotic skeletal manifestation, while only 39 patients (38.6%) had monostotic involvement. In contrast to these findings, in the entire cohort of 754 patients more than 75% of patients presented with monostotic disease manifestation. The peak incidence of spinal PDB was found at 65.02 (SD ± 11.55) years of age with a small number of cases occurring in the fourth and fifth decade. A steady increase in cases was noted from the sixth decade onward and a peak disease incidence was reached during the eight decade.

The lumbar spine was the most common site of PDB manifestation (62.2%), followed by the thoracic spine (29.6%). In 8.2% of patients, the cervical spine was involved. Here, four cases (50%) showed disease manifestation of C2. In each case, conventional X-ray images of the affected spinal segment were performed to document disease extent and to visualize a potential biopsy site. Here, typical radiological changes of pagetic vertebral bodies consisted of enlargement in width and height and reduced translucency leading to a typical “ivory vertebra” appearance. Serum ALP levels were elevated in 86.0% of patients with an average level of 256.05 U/L (SD ± 182.74). The normal range for serum ALP set by our institution’s laboratory was 50–130 U/L.

Histological and quantitative static histomorphometry data

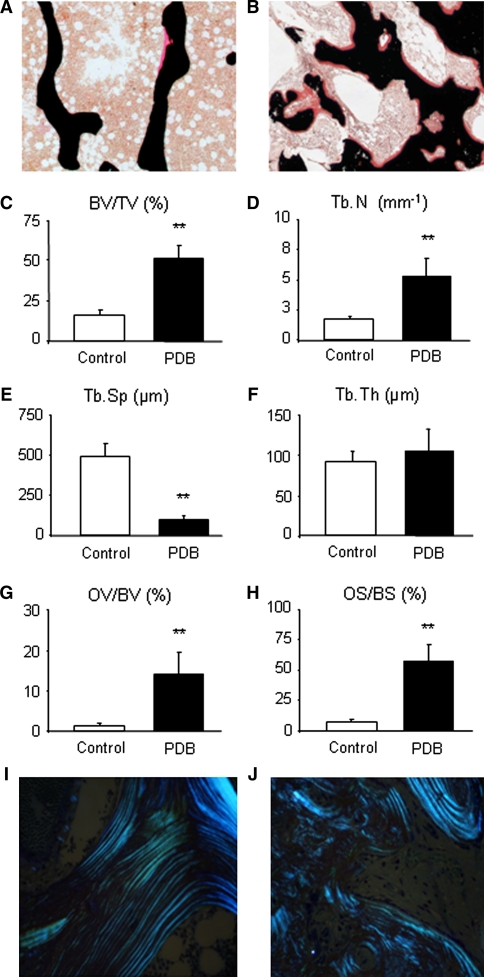

When comparing bone biopsies obtained from skeletal-intact donors at autopsy with biopsies obtained from patients with PDB, significant changes of structural parameters of trabecular bone (i.e., trabecular number, thickness, spacing, and connectivity) were observed for all cases of PDB. Von Kossa/Van Giesson staining of non-decalcified spinal bone specimens displayed typical changes of trabecular micro-architecture (Fig. 1a, b). Histomorphometric quantification of trabecular bone volume revealed a >2-fold increase in biopsies derived from PDB patients (BV/TV: 15.95 ± 3.24% vs. 48.06 ± 13.48%; p ≤ 0.001). This finding was accompanied by an increase in trabecular number (Tb.N: 1.72 ± 0.26 mm−1 vs. 5.06 ± 1.72 mm−1; p ≤ 0.001) and a decrease of trabecular separation (Tb.Sp: 494.05 ± 83.14 μm vs. 90.58 ± 28.94 μm; p ≤ 0.001). Interestingly, trabecular thickness (Tb.Th: 91.64 ± 12.81 μm vs. 98.55 ± 33.43 μm; p = 0.150) was not significantly altered (Fig. 1c–f). Moreover, the degree of mineralization in PDB samples appeared severely changed when compared with control specimens. PDB patients showed a significant increase in osteoid volume (OV/BV: 1.36 ± 0.64% vs. 13.69 ± 5.48%; p ≤ 0.001; Fig. 1g) and osteoid surface (OS/BS: 6.78 ± 2.90% vs. 54.72 ± 15.88%; p ≤ 0.001; Fig. 1h). Moreover, using polarized light, we analyzed control samples where regular orientation and even distribution of collagen fibers were observed (Fig. 1i). In sharp contrast to these observations, PDB samples showed patterns of collagen fiber distribution lacking orientation where no uniform directions could be detected. Here, a rather random distribution indicative of woven bone was observed (Fig. 1j). When histomorphometric parameters were compared to data obtained for iliac crest biopsies, neither statistically significant differences for trabecular parameters such as BV/TV, Tb.Th., Tb.N. nor for osteoid parameters (OV/BV, OS/BS) were observed.

Fig. 1.

Trabecular bone characteristics of spinal PDB biopsies. a Histological Von Kossa/van Giesson staining of a bone specimen harvested from a skeletal-intact donor at autopsy and b that of a PDB biopsy showing typical pagetic changes (50× magnification). Note the increase in bone and osteoid volume (indicated by red staining) leading to a dense trabecular architecture and a significant increase in c bone volume (BV/TV), due to an increase in d trabecular number (Tb.N) and a decrease in e trabecular separation (Tb.Sp). f Trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) is not significantly changed. Additionally, g osteoid volume (OV/BV) and h osteoid surface (OS/BS) are significantly increased, indicating a mineralization deficiency in all PDB samples. i With the help of polarized light, correct orientation of collagen fibers in one uniform direction can be detected in healthy individuals. j PDB biopsies typically show a random distribution of collagen fibers indicative of woven bone (both 200× magnification). Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 29). *Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) and **highly significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) as determined by Student’s t test

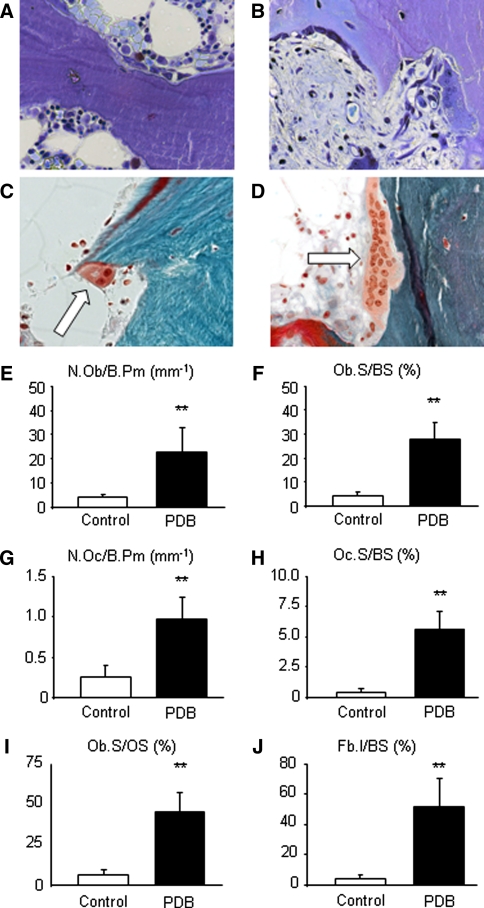

To determine the observed difference’s cellular basis, we used toluidine blue staining to visualize and quantify the number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. A great increase in cell size and number was observed for both cell types. Multi-nucleated osteoclasts with >12 nuclei per cell were frequently detected at the trabecular bone surface (Fig. 2a–d). Histomorphometric analysis revealed a fivefold increase of osteoblast number (N.Ob/B.Pm: 4.03 ± 1.30 mm−1 vs. 21.27 ± 10.51 mm−1; Fig. 2e) and surface (Ob.S/BS: 4.41 ± 1.48% vs. 26.35 ± 8.53%; Fig. 2f) in PDB patients. Osteoclast numbers (N.Oc/B.Pm: 0.26 ± 0.15 mm−1 vs. 0.92 ± 0.33 mm−1; p ≤ 0.001) and surface (Oc.S/BS: 0.35 ± 0.19% vs. 5.37 ± 1.78%; p ≤ 0.001) were increased to a similar extent in PDB lesions (Fig. 2g–h). Pagetic osteoclasts displayed an altered morphology (i.e., an increased size and number of nuclei). To verify if the increase in osteoid volume described above was caused by a defect in bone matrix mineralization or a result of increased osteoblast activity, we finally evaluated the osteoblast surface relative to the osteoid surface. Here, a significant increase in Ob.S/OS (5.41 ± 1.37% vs. 46.08 ± 14.40%; p ≤ 0.001; Fig. 2i) was observed in comparison to control individuals, suggesting, that the increase in osteoid rather results from an increased osteoblast number and function. In addition, whereas fibrosis was absent in healthy individuals, we found that >50% of the bone surface was covered with fibrotic tissue in PDB patients (Fb.I/BS: 1.0 ± 0.3 vs. 55.43 ± 19.56%; p ≤ 0.001; Fig. 2j).

Fig. 2.

Cellular characteristics of spinal PDB biopsies. a Toluidine blue staining of a block specimen of a skeletal-intact donor and b PDB patient (400× magnification). Note the increase in osteoblasts and osteoclasts, covering the trabecular surface. c Masson-Goldner staining (400× magnification) of a specimen from a skeletal-intact donor showing a regular sized osteoclast (white arrow) with two visible nuclei. d Note the increase in osteoclast size in this giant osteoclast with >12 nuclei displayed here in Masson-Goldner staining (400× magnification) in a PDB sample. Histomorphometric analysis revealed a significant increase in e osteoblast number (N.Ob/B.Pm) and f surface (Ob.S/BS), as well as g osteoclast number (N.Oc/B.Pm) and h surface (Oc.S/BS). i Additionally, an increase in osteoblast number per osteoid surface (N.Ob/OS) was found as an indirect sign of accelerated bone formation as a result of increased osteoblast activity. j Whereas fibrous tissue (Fb.I/BS) is rarely found in healthy individuals, it was found to cover more than 50% of the bone surface in PDB samples. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 29). *Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) and **highly significant differences (p < 0.001) as determined by Student’s t test

When the histomorphometric parameters described above were compared to data obtained for iliac crest biopsies, no statistically significant differences for cellular parameters were observed.

Correlation of histomorphometric data related to each spinal segment

After histomorphometric parameters for trabecular bone architecture had been assessed for PDB biopsies of the spine, they were analyzed with respect to location (lumbar spine L1–L5, thoracic spine Th1–Th12, cervical spine C1–C7). It was of interest to detect cellular or trabecular changes characteristically occurring in certain locations. Therefore, all affected vertebral bodies were compared to one another singularly (e.g., L1 vs. Th 12) and spinal segments were compared to one another (e.g., lumbar vs. thoracic spine).

Comparison of histomorphometric parameter BV/TV measured in skeletal-intact autopsy specimens revealed significantly greater bone density in the cervical spine when compared with the lumbar spine (Fig. 3; p < 0.05). In contrast to this finding, no differences in terms of disease activity, trabecular micro-architecture or parameters of non-mineralized bone (osteoid) were observed between the segments analyzed (Fig. 3). Also, disease extent appeared similarly pronounced in most spinal segments and comparable in all vertebral bodies analyzed.

Fig. 3.

Correlation of trabecular bone parameter BV/TV and osteoid parameter OV/BV with PDB location in the spine. a When trabecular parameter BV/TV (bone volume per tissue volume) was used to compare average bone density of cervical with lumbar vertebral bodies, significantly greater values were observed for the cervical spine in healthy individuals. b PDB samples on the other hand revealed severe increases in BV/TV values, but did not show differing disease manifestation in any spinal location. c Analysis of non-mineralized bone (osteoid) parameter OV/BV (Osteoid volume per bone volume) in healthy control individuals did not show differences between cervical, thoracic or lumbar segments. d Spinal bone biopsies obtained from PDB patients revealed severely increased osteoid volumes, which was equally pronounced in all spinal segments analyzed. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 29). *Statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) as determined by Student’s t test

Correlation of disease activity with biological markers and clinical features

According to ASBMR standards, disease activity was defined as both osteoblast and osteoclast numbers per bone perimeter (NOb/BPm and NOc/BPm, respectively), as well as surface indices for osteoblasts and osteoclasts per bone surface (ObS/BS and OcS/BS, respectively) and osteoid surface (ObS/OS). All parameters described above were correlated with biological marker sALP, clinical features such as monostotic or polyostotic involvement and sex. Neither osteoblast nor osteoclast numbers showed significant correlations with sALP levels and did not appear to be significantly associated with sex, or monostotic or polyostotic involvement.

Correlation of histomorphometric data obtained from iliac crest biopsies of PDB patients

In addition to comparing vertebral bodies to one another and spinal segments among each other, histologic changes typical of PDB in the spine were compared to histomorphometric data obtained for iliac crest biopsies from this cohort’s patients. Comparison of iliac crest biopsies with spinal biopsies did not reveal any significant differences. Both, cellular parameters as well as trabecular and osteoid parameters showed very comparable results; therefore, no differences in disease activity or disease severity were observed.

Correlation of disease frequency with location in the spine

Finally, vertebral body heights measured for skeletal-intact donors were set into relation with disease occurrence of PDB of the spine. In autopsy specimens, vertebral body heights of the cervical spine (C1–C7) were found to measure 13.5 mm (±1.7) on average, whereas vertebral bodies of the thoracic spine (Th1–Th12) were significantly larger with an average height of 20.2 mm (±3.2). As expected, the lumbar spine (L1–L5) presented with the largest vertebral bodies where the average height measured 27.8 mm (±1.7). When vertebral body heights measured in skeletal-intact individuals were set into correlation with disease occurrence and location in PDB cases, statistically significant correlations were observed (Pearson’s correlation coefficient = 0.83; p < 0.05) indicating that the occurrence of PDB of the spine appears to be associated with vertebral body height independent of disease activity.

Discussion

Few comparative histological analyses or histomorphometric data of bone biopsies extracted from bones affected by PDB can be found in today’s literature [11]. The limited amount of data available might be due to the mostly straightforward diagnostic steps usually consisting of the patient’s complaints together with a typical increase in sALP and characteristic radiological changes. Additionally, improvements in the quality of radiological imaging have made invasive procedures like bone biopsies infrequent. Also, rapid improvement of clinical symptoms and decrease of sALP levels after adequate antiresorptive therapy is regularly found [1–7]. Some case studies include histological samples, mainly obtained from the iliac crest, where descriptions of typical disease characteristics can be found. Unfortunately, these studies mostly present decalcified histology where evaluation of non-mineralized bone (osteoid) was not possible. In 1980, Meunier et al. [11] for the fist time presented a histomorphometric analysis of 72 PDB cases describing typical changes of both bone architecture and cellular parameters found in PDB. Almost 30 years later, Seitz et al. [1] performed a study analyzing an even larger cohort consisting of 754 patients with histologically proven PDB. Here, 247 iliac crest biopsies of non-decalcified bone samples were evaluated histologically. The results were noteworthy, as next to a detailed description of the disease’s epidemiology, emphasis was laid on skeletal distribution. A total of 101 of the cohort’s patients presented with PDB involving the spine. In addition to iliac crest biopsies, biopsies of the affected vertebral body were available for 29 individuals. Our primary objective was therefore to accomplish a first histological analysis of those samples and to compare these findings to matched-pair samples from skeletal-intact individuals. Furthermore, a detailed comparison of spinal data with data obtained for iliac crest biopsies was performed.

Our analysis of biopsies obtained from skeletal-intact control subjects revealed that the lumbar spine possesses a significantly lower bone volume per tissue volume (BV/TV) when compared with cervical spine samples. Also, as described in previous studies, the lumbar spine can be associated with significantly greater vertebral height and bone volume when compared with the thoracic and the cervical spine [12].

Since the majority of PDB cases of the spine were found in the lumbar spine, we hypothesized that due to the specific disease allocation of PDB and the variations in trabecular architecture observed in healthy control specimens, different spinal segments in PDB might present with different disease activities and bone remodeling characteristics. However, when cellular and trabecular parameters of different spinal segments were compared with one another, no significant differences were observed. With the observation in mind that in healthy individuals the cervical spine presented with significantly greater BV/TV values than the lumbar spine, these are most interesting data. The convergence of all trabecular characteristics in PDB patients indicates that the former greater bone density in the cervical spine is not maintained throughout the disease and that a maximum increase of all trabecular parameters might have been reached. Also, disease activity, measured by cellular parameters like osteoblast and osteoclast numbers, did not differ significantly in any of the spinal segments, which might further support the hypothesis that a maximum disease activity in the segments analyzed might have been reached.

Next to a close examination of the control subject’s trabecular characteristics, average vertebral body heights in skeletal-intact individuals were measured and correlated with the distribution of PDB in the spine. Here, a positive correlation was observed. The greater the vertebral body height, the more likely it became that the vertebral body showed pagetic changes. Together with the observation that vertebral bodies with lower BV/TV values are more commonly affected by the disease, it can further be speculated that vertebral body height and size might play an additional role in PDB incidence. This speculation is supported by the fact that in this study, C2 presented as one of the primary disease locations if involvement of the cervical spine was found. This does not contradict reports that identify the atlanto-axial region as a rare disease location [13, 14]. However, detailed analyses of affected C2 vertebral bodies have up to date not been performed. Therefore, no explanation for this rare observation can be found. C2 is significantly larger than the other six cervical vertebrae, but its bone architecture does not appear to differ significantly from other vertebral bodies [15].

It has been speculated that biomechanical factors such as increased loading on the lumbar spine may contribute to the high prevalence of PDB cases in this region [3]. This might be a possible explanation for the higher disease occurrence in the lumbar spine, but this assumption would also lead to the conclusion that within the cervical spine the atlas should be affected more often than C2. Among the 101 cases evaluated in this study, only one case of atlas involvement was found. We therefore believe that next to biomechanical properties, other factors such as bone density, bone size or even the vertebral body’s blood supply might influence the occurrence of PDB.

We further hypothesized that spinal segments affected by PDB might present with different trabecular micro-architectural and cellular characteristics when compared with bone biopsies obtained from extra-spinal locations. As an extra-spinal reference location, we chose the most common site of PDB, the iliac crest. Biopsy samples were readily available due to the study performed by Seitz et al. [1]. We are aware of the fact that in terms of trabecular architecture, vertebral bodies do not differ greatly from the iliac crest. Interestingly though, this comparison did not reveal any significant differences for the trabecular or cellular parameters. One possible explanation for the lack of differences could be that the disease’s initial lytic phase, which represents a mainly osteoclastic activity, is infrequently detected in bones with a high trabecular/cortex ratio like vertebra and ilium [16]. Additionally, radiological studies were able to confirm that vertebral involvement during the time of diagnosis is virtually always complete [16]. This might again strengthen the hypothesis that in most biopsies taken from vertebra or iliac crest, a maximum disease activity and possibly a mixed osteoblastic/osteoclastic phase might have been reached. In order to clarify this issue, it would be helpful to include biopsies from long bones such as the femur or tibia. Here, disease progression has been reported to be slower and in early stages of the disease different phases might be found [16].

As a limitation of this study, it needs to be pointed out that no systematic follow-up data of our cases documenting the disease’s course or progression are available. Also, as cases date back to 1972, clinical data are clearly limited. Histological differences in disease activity were neither observed in different spinal locations nor in comparison to iliac crest biopsies. Therefore, one of the studies initial intentions to investigate if disease activity in different locations could have an influence on its medical treatment had to be displaced. Hopefully, future studies with a histological background will be able to aid in the advancement of medical treatment options in PDB.

Additionally, missing follow-up data together with similar disease activities in all locations analyzed clearly limit the study’s clinical relevance. However by presenting a series of rare spinal PDB biopsies, we believe to have established a unique study with more of a histological background than a clinical one. As no systematic approach to PDB of the spine is available and PDB activity in the spine does not differ significantly from PDB of the iliac crest, we decided to narrow our conclusions down to our histological findings.

One aspect of the study’s clinical relevance is that PDB is a frequent bone disease with spinal manifestation in approximately 13% of patients. Spinal surgeons need to be aware of spinal manifestation of PDB when differential diagnoses of bone lesions are in question. As cellular activity in our samples was generally high, one therapeutic consequence is that medical suppression of osteoclast activity might be of paramount importance. Our recommendation would be that in cases requiring surgical interventions, the activity of pagetic lesions should be blocked prior to invasive actions.

The time from the beginning of pagetic changes in bone to presentation of the maximum disease manifestation can only be estimated. Due to the findings described above, it could be speculated that skeletal elements with lower BV/TV might present with faster disease progression. This, however, does not appear to be likely since disease activity was very similar in different skeletal segments analyzed in this study leading to the careful estimation that, independent of the disease location, disease extent in most segments might be comparable. This conclusion could be contradicted by the assumption that at the time the PDB biopsy was taken, a maximum disease activity might have already been reached, leading to an equalization of all parameters presented in this study. Another factor that might have had an effect on our results is that biopsies, independent of their spinal location, were either obtained under CT-guidance from the center of the vertebral body or as block specimens from similar locations. ASBMR standards recommend examination and evaluation of trabecular bone from exactly this location if the diagnosis of Paget’s disease is in question. However, radiologically the most frequent mechanisms of vertebral body expansion appear to be periosteal bone apposition and endosteal bone absorption, which are usually responsible for vertebral body enlargement and increased bone marrow space [17, 18]. It can therefore be discussed if biopsies taken from periosteal surface where new bone formation radiologically appears to predominate might have revealed even higher disease activities than the ones described in this study. In this context, the activities of bone remodeling in spinal areas might differ from extra-spinal locations such as the iliac bone.

In summary, this study presents the first comparative analysis of a large collection of histologically proven PDB samples obtained from vertebral bodies and compares these findings to data from skeletal-intact age-, location- and sex-matched individuals. Since neither the disease’s etiology nor reasons for its preference of the spine, next to other skeletal sites, are known, this study might lead to a better understanding of the skeletal distribution of PDB. Pagetic manifestation in vertebral bodies appears to be associated with bone size and vertebral body height, in general, and bone density, in particular. Disease activity does not show differences in the spinal segments involved or when comparing spinal to extra-spinal disease manifestations.

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

J. M. Pestka and S. Seitz contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Seitz S, Priemel M, Zustin J, Beil FT, Semler J, Minne H, Schinke T, Amling M. Paget’s disease of bone: histologic analysis of 754 patients. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:62–69. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman RD. Musculoskeletal manifestations of Paget’s disease of bone. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1121–1127. doi: 10.1002/art.1780231008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meunier PJ, Salson C, Mathieu L, Chapuy MC, Delmas P, Alexandre C, Charhon S (1987) Skeletal distribution and biochemical parameters of Paget’s disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 217:37–44 [PubMed]

- 4.Hadjipavlou A, Lander P. Paget disease of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1376–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirra JM, Brien EW, Tehranzadeh J. Paget’s disease of bone: review with emphasis on radiologic features, Part I. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24:163–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00228918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirra JM, Brien EW, Tehranzadeh J. Paget’s disease of bone: review with emphasis on radiologic features, Part II. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24:173–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00228919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davie M, Davies M, Francis R, Fraser W, Hosking D, Tansley R. Paget’s disease of bone: a review of 889 patients. Bone. 1999;24:11S–12S. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis RJ, Jacoes B, Marchisello PJ, Bullough PG (1977) Monostotic Paget’s disease of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 127:208–211 [PubMed]

- 9.Amling M, Werner M, Posl M, Maas R, Korn U, Delling G. Calcifying solitary bone cyst: morphological aspects and differential diagnosis of sclerotic bone tumours. Virchows Arch. 1995;426:235–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00191360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meunier PJ, Coindre JM, Edouard CM, Arlot ME. Bone histomorphometry in Paget’s disease. Quantitative and dynamic analysis of pagetic and nonpagetic bone tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1095–1103. doi: 10.1002/art.1780231005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Limthongkul W, Karaikovic EE, Savage JW, Markovic A. Volumetric analysis of thoracic and lumbar vertebral bodies. Spine J. 2010;10:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saifuddin A, Hassan A. Paget’s disease of the spine: unusual features and complications. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:102–111. doi: 10.1053/crad.2002.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown HP, LaRocca H, Wickstrom JK. Paget’s disease of the atlas and axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:1441–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoganandan N, Pintar FA, Stemper BD, Baisden JL, Aktay R, Shender BS, Paskoff G, Laud P. Trabecular bone density of male human cervical and lumbar vertebrae. Bone. 2006;39:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.01.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vande Berg BC, Malghem J, Lecouvet FE, Maldague B. Magnetic resonance appearance of uncomplicated Paget’s disease of bone. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2001;5:69–77. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadjipavlou AG, Gaitanis LN, Katonis PG, Lander P. Paget’s disease of the spine and its management. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:370–384. doi: 10.1007/s005860100329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lander PH, Hadjipavlou AG. A dynamic classification of Paget’s disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:431–438. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B3.2942548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]