Abstract

The human angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) gene is one of the most investigated candidate genes for cardiovascular diseases (CVD), but the understanding of its role among the elderly is vague. Therefore, this study focuses at: (a) testing the association of ACE polymorphism with CVD risk factors among the elderly, and (b) detecting the possible unequal distribution of ACE genotypes between senescent and younger segments of the European populations. The association of ACE I/D polymorphism with CVD health status [hypertension (HT), obesity, dislypidemia] in 301 very old subjects (88.2 ± 5 years; F/M = 221/80) was tested by means of logistic regression analysis. The meta-analysis of D allele frequency in general vs. elderly (80+ years) groups was conducted using all publicly available data for European populations comprising both age cohorts. Multiple multinomial logistic regression revealed that within this elderly sample, age (younger olds, 80–90 years), female sex (OR = 3.13, 95% CI = 1.59–6.19), and elevated triglycerides (OR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.29–4.95) were positively associated with HT, while ACE polymorphism was not. It was also established that the DD genotype was twice as high in 80+ cohort compared to general population of Croatia (p < 0.00001). This trend was confirmed by the meta-analysis that showed higher D allele frequencies in olds from nine of ten considered European populations (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.08–1.31). The data in elderly cohort do not confirm previously reported role of ACE DD genotype to the development of HT. Moreover, meta-analysis indicated that ACE D allele has some selective advantage that contributes to longevity in majority of European populations.

Keywords: Aged, Aged 80 and over, Longevity, ACE I/D polymorphism, Hypertension, Meta-analysis

Keywords: Life Sciences, Molecular Medicine, Geriatrics/Gerontology, Cell Biology

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are multifactorial diseases involving heart, brain, and peripheral circulation. They are among the leading causes of death and disease burden in both high- and low-income countries (Lopez et al. 2006). According to the information published by Central Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Croatia, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases were the most common cause of death in 2009 for both men and women, constituting over 39% of all deaths (Croatian Bureau of Statistics 1992).

The human angiotensin converting enzyme gene (ACE gene) is one of the most investigated candidate genes for CVD. It converts angiotensin I into a physiologically active angiotensin II, which is a potent vasopressor and aldosterone-stimulating peptide that controls blood pressure (BP) and fluid electrolyte balance. ACE also degrades bradykinin to inactive fragments, reducing the serum levels of endogenous vasodilators (Brewster and Perazella 2004; Fleming 2006). The insertion or deletion (I/D) of a 287-bp-long Alu repeat element in the intron 16 of this gene was proven associated with the altered levels of circulating ACE enzyme (Rigat et al. 1990) as well as with cardiovascular pathophysiologies (Cambien et al. 1992; Jeunemaitre et al. 1992a; Keavney et al. 1995). Some of the conducted studies showed positive association of DD genotype and increased risk of myocardial infarction and atherosclerosis (Agerholm-Larsen et al. 2000; Sayed-Tabatabaei et al. 2003). However, a great number of studies, including meta-analyses, associating ACE I/D with hypertension (HT), cardiomyopathy, and coronary arthery disease showed controversial results (Jeunemaitre et al. 1992b, 1997; Lindpaintner et al. 1995; Staessen et al. 1997; Sharma 1998; Dikmen et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2008; Vaisi-Raygani et al. 2010). Furthermore, recent studies have unravelled roles of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) and, particularly, its main effector molecule angiotensin II in inflammation, autoimmunity, and aging (Papadopoulos et al. 2000; Pueyo et al. 2000; Suzuki et al. 2003; Kitayama et al. 2006; de Cavanagh et al. 2007; Platten et al. 2009; Benigni et al. 2010).

Although widely explored, the contribution of ACE I/D and plenty other genetic and environmental risk factors across age spectrum is still unclear. Given the fact that our sample consists of 80 years old and older subjects in rather good physical and mental condition, it is plausible to expect that they have some protective factors that contributed to their good health and longevity. Therefore, we hypothesize that ACE I/D frequencies differ across population age distribution as a consequence of its association with CVD, its risk factors, and hence mortality.

As HT is recognized as one of the main CVD risk factors (Clarke et al. 2009), in this study, we will first investigate the effect of ACE I/D polymorphism on HT in a Croatian 80+ years population. Furthermore, we will test the association between ACE I/D polymorphism and longevity comparing our sample with previously reported frequencies for the general Croatian population aged 18–80 years (Barbalić et al. 2004). Finally, to test whether I/D allele frequency trend really exists, we will conduct a meta-analysis for both general and 80+ population for the allele frequency distribution in European populations.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A field study was carried out from 2007 to 2009. Participants were recruited from all 11 homes for elderly and infirm in the property of the City of Zagreb, and two private homes located in Zagreb County. The 80 years old and older residents were invited to participate voluntarily, and they all signed written, informed consent. Altogether, 301 examinees participated in this study (222 women, 79 men, age range 80–101 years, mean 88.2 ± 5 years). This sample represents 2.86% of the population of Zagreb City in the age group 80+ years (Croatian Bureau of Statistics 1992).

Study protocol

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Anthropological Research. It consisted of an extensive interview including the mini-mental state examination, the mini nutritional assessment, BP measurement, short anthropometry, ultrasound measurement of bone mineral density, and collection of venipuncture specimens for biochemical parameters and genetic analyses. Questionnaire included detailed questions regarding sociodemographic status, health status, medical history, nutritional habits, and examinee’s satisfaction with his/her quality of life. Trained examiners filled out a questionnaire during a face-to-face interview. Only subset of the obtained data is presented here and explained in more details.

Short anthropometry was undertaken following standard international biological programme protocol (Weiner and Lourie 1981). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by squared height in meters (kg/m2). On the basis of BMI (WHO Classification; WHO 2000), subjects were divided into three groups: underweight (BMI < 18.50 kg/m2), normal (BMI 18.50–24.99 kg/m2), and overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2).

BP was measured in a seated position by the physician using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer and stethoscope after participants rested for 15 min. The selection criteria for hypertensive cases were any of the following: systolic BP equal to or higher than 140 mmHg, diastolic BP equal to or higher than 90 mmHg, subject’s statement that she/he is hypertensive (indicating previous diagnosis of HT by personal physician), and subject’s drug treatment history of HT.

Whole blood samples were obtained by venipuncture and collected for every subject into three tubes for the following analyses: blood serum biochemical analyses, hematological analysis, and DNA extraction. Serum and blood cells analyses were performed following standard internationally agreed procedures. Biochemical analysis included triglyceride and cholesterol measurements [total, high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL and LDL), and atherosclerosis index].

ACE genotyping

DNA was extracted by a salting-out method (Miller et al. 1988). Genomic DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers 5′-CTG GAG ACC ACT CCC ATC CTT TCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAT GTG GCC ATC ACA TTC GTC AGA T-3′ (reverse). PCR cycling was in a touchdown regime described previously (Kalaydjieva et al. 1999).

The PCR products, 490-bp-long (I) and 190-bp-long (D) fragments, were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis using 2%-agarose gel and visualized with SYBR Gold stain.

A selection of studies for meta-analysis

In order to compare ACE I/D polymorphism D allele frequency distribution in Croatians and other Europeans in general and 80+ populations, electronic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE and Science Direct) were searched up to April 2010 for similar studies. The keywords used for the search were: (ACE I/D OR ACE id OR ACE indel OR ACE Alu) AND (longevity OR senescence OR general population). All languages were searched initially, but only English language articles were selected. Furthermore, the references of all selected publications were searched for additional studies. Slovakian 80+ age group was obtained through personal correspondence with Prof. Daniela Sivakova.

The primary search generated more than 647 potentially relevant articles, 38 of which met the inclusion criteria. Studies were selected if they met all of the following:

Studied populations were Europeans.

Studies contained D allele frequency data for general and/or older (80+ years) populations.

There were available data concerning D allele frequency for both age subsets from the same European country.

The studies of ten European populations satisfied the previous conditions: Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Spain, and United Kingdom. A list of selected studies is presented in Table 1. All participants in the conducted studies were Caucasians. If there was more than one study conducted in the same country for a certain age group, the reported D allele frequency was calculated by sample size weighting (pondering).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 43 studies included in the meta-analysis presented by countries

| Country | Reference | Age (years) | Age group | Sample size | Gender distribution M/F | Source of sample | Genotype distribution | Allele frequencies (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DD | ID | II | D allele | I allele | |||||||

| Croatia | Barbalić et al. 2004 | 18–80 | 1 | 172 | Not reported | Healthy general population | 38 | 94 | 40 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Present study | 80–101 | 2 | 301 | 79/222 | Population from retirement homes in Zagreb | 129 | 110 | 62 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |

| Denmark | Agerholm-Larsen et al. 1997 | 43.1 ± 0.2 | 1 | 3,191 | 1,737/1,454 | General population from Copenhagen | Not reported | 0.52 | 0.48 | ||

| Bladbjerg et al. 1999 | 20–64 | 1 | 199 | 124/75 | Healthy young blood donors | 51 | 102 | 46 | 0.51 | 0.49 | |

| Hadjadj et al. 2007 | 44.8 ± 11.0 | 1 | 382 | Not reported | EURAGEDIC study | Not reported | 0.51 | 0.49 | |||

| Bladbjerg et al. 1999 | >100 | 2 | 185 | 47/141 | Volunteers from centenarian population | 49 | 95 | 41 | 0.52 | 0.49 | |

| Finland | Fuentes et al. 2002 | 35–55 | 1 | 454 | 167/288 | FINRISK survey | Not reported | 0.57 | 0.43 | ||

| Islam et al. 2006 | 34.35 ± 3.16 | 1 | 224 | 121/103 | Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study | 79 | 106 | 39 | 0.59 | 0.41 | |

| Hadjadj et al. 2007 | 44.8 ± 11.0 | 1 | 468 | Not reported | EURAGEDIC study | Not reported | 0.56 | 0.44 | |||

| Myllykangas et al. 2000 | >85 | 2 | 203 | 40/163 | Vantaa 85+ study | 65 | 105 | 33 | 0.58 | 0.42 | |

| France | Marre et al. 1997 | 44 ± 9 | 1 | 346 | 180/166 | Healthy nondiabetic general population | 117 | 154 | 75 | 0.56 | 0.44 |

| Hadjadj et al. 2007 | 44.8 ± 11.0 | 1 | 273 | Not reported | EURAGEDIC study | Not reported | 0.54 | 0.46 | |||

| Schachter et al. 1994 | >99 | 2 | 338 | 44/294 | Centenarian population | 134 | 148 | 56 | 0.62 | 0.33 | |

| Blanche et al. 2001 | >100 | 2 | 560 | 94/466 | Centenarian population | 196 | 261 | 103 | 0.58 | 0.42 | |

| Richard et al. 2001 | >80 | 2 | 152 | Not reported | General population | 48 | 67 | 37 | 0.54 | 0.46 | |

| Germany | Schunkert et al. 1994 | 45–59 | 1 | 290 | 149/141 | General population of Augsburg | Not reported | 0.54 | 0.46 | ||

| Busjahn et al. 1997 | 34 ± 14 | 1 | 139 | 34/105 | 91 monozygotic and 41 dizygotic twins (included only one member of each pair) | 33 | 79 | 37 | 0.52 | 0.48 | |

| Mondry et al. 2005 | 41.24 ± 12.66 | 1 | 719 | 419/399 | General population of Weisswasser | 193 | 356 | 170 | 0.52 | 0.48 | |

| Luft 1999 | 80+ | 2 | 349 | Not reported | 80+ population of Berlin | 118 | 159 | 72 | 0.57 | 0.43 | |

| Italy | Arbustini et al. 1995 | 35 ± 13 | 1 | 290 | 210/80 | Healthy blood donors | 120 | 124 | 46 | 0.63 | 0.37 |

| Paterna et al. 2000 | 37.5 ± 9.3 | 1 | 201 | 74/127 | Healthy control for migraine patients (no history of CVD) | 75 | 101 | 25 | 0.62 | 0.38 | |

| Di Pasquale et al. 2004 | 25–55 | 1 | 684 | 443/241 | Healthy volunteers (free of CVD) | 225 | 335 | 124 | 0.57 | 0.43 | |

| Paolisso et al. 2001 | >100 | 2 | 41 | 15/26 | Healthy population | 15 | 20 | 6 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |

| Panza et al. 2003 | 100 ± 2 | 2 | 82 | 20/62 | Healthy population from Southern Italy | 38 | 34 | 10 | 0.67 | 0.33 | |

| Nacmias et al. 2007 | 102.4 ± 4.6 | 2 | 111 | 23/88 | Healthy control for Alzheimer disease patients (no neurological disorder) | 57 | 40 | 14 | 0.69 | 0.31 | |

| Corbo et al. 2008 | >77 (82.2 ± 4.8) | 2 | 151 | 73/78 | Healthy subjects in post-reproductive age: LONCILE study (Salerno, sothern Italy) | 61 | 71 | 19 | 0.64 | 0.36 | |

| Russia | Dolgikh et al. 2001 | 25–64 | 1 | 945 | 603/342 | WHO Monica (Novosibirsk population) | Not reported | 0.52 | 0.48 | ||

| Miloserdova et al. 2001 | 34.2 ± 2.37 | 1 | 50 | Not reported | Random sample of Moscow population | Not reported | 0.56 | 0.44 | |||

| Nazarov et al. 2001 | 32 ± 10 | 1 | 449 | 269/180 | 111 students of St Petersburg University and 338 blood donors (Russians of European and Siberian descent, 3:1) | Not reported | 0.50 | 0.50 | |||

| Miloserdova et al. 2001 | 83.17 ± 3.39 | 2 | 50 | Not reported | Random sample of Moscow population | Not reported | 0.68 | 0.32 | |||

| Slovakia | Dankova et al. 2009 | 40–60 (49.54) | 1 | 167 | 45/122 | Volunteers recruited at random (different localities in Slovakia) | 47 | 82 | 38 | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| Sivakova et al. 2009 | 82.85 ± 2.68 | 2 | 61 | Not reported | Physically and mentally fit volunteers from different regions of Slovakia | 20 | 27 | 14 | 0.55 | 0.45 | |

| Spain | Riera-Fortuny et al. 2005 | 60.2 ± 9.5 (35–79 years) | 1 | 182 | 127/55 | Healthy control coronary heart disease nor CVD risk factors | 67 | 83 | 21 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| Hernández Ortega et al. 2002 | 54 ± 10 | 1 | 315 | 223/92 | Randomly selected Gran Canaria Island population with no history of CVD | 137 | 132 | 136 | 0.64 | 0.36 | |

| Alía et al. 2005 | 44 | 1 | 104 | 46/58 | Healthy sarcoidosis controls | 34 | 51 | 19 | 0.57 | 0.43 | |

| Villar et al. 2008 | 18–75 | 1 | 364 | 182/182 | Randomly selected Canarian (Spanish) population from all seven islands | 152 | 155 | 57 | 0.63 | 0.37 | |

| Alvarez et al. 1999 | >85 | 2 | 117 | Not reported | Healthy Alzheimer controls | 43 | 58 | 16 | 0.62 | 0.38 | |

| United Kingdom | Samani et al. 1996 | 20–77 | 1 | 537 | 299/238 | Healthy control for CHD from Leicester (N = 237) and Sheffield (N = 300) | 158 | 259 | 120 | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| Sharma et al. 1997 | 41.4 ± 11.9 (19–70) | 1 | 146 | 59/87 | Volunteers attending the Regional Blood Transfusion Service | 44 | 63 | 39 | 0.52 | 0.48 | |

| Garrib et al. 1998 | 38.2 | 1 | 100 | Not reported | Healthy control for sarcoidosic patients | Not reported | 0.53 | 0.47 | |||

| Jackson et al. 2000 | 18–65 | 1 | 478 | Not reported | Blood donors from Cambridge | 135 | 241 | 102 | 0.53 | 0.47 | |

| Galinsky et al. 1997 | >79 | 2 | 270 | 100/170 | Cambridge City population (longitudinal study of cognitive function and aging) | 87 | 128 | 55 | 0.56 | 0.44 | |

| Kehoe et al. 1999 | 80.8 ± 4.5 | 2 | 111 | Not reported | Healthy Alzheimer controls (London population) | 41 | 48 | 22 | 0.59 | 0.41 | |

Age data in this table are not presented uniformly because they were reported differently in the papers: some authors preferred age range, others mean age (SD) or just reported that subjects were over a certain age. We divided them in two groups: group one, for subjects aged 18–80 years, and group two, for those aged 80+ years (or if the mean age of the entire group was 80+). Each study group consisted of both females and males. Genotype distribution is reported in absolute numbers.

Statistical analysis

We determined ACE ID genotype frequencies by direct counting, and allele frequencies were calculated from the genotype frequencies. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was evaluated by the Chi-square (χ2) test. We tested differences in CVD risk factors between sexes using Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s Chi-square test. Same factors were analyzed using t test in hypertensives vs. nonhypertensives.

Several multivariate logistic regression models were tested to verify the combined effect of several risk factors on HT, and the best regression model was taken into account. The following variables were tested: age, sex, BMI, waist/hip ratio, cholesterol (total, HDL, and LDL) and triglyceride serum levels, ACE ID genotypes and I and D alleles frequency. The analyses were performed by SPSS 10.0 statistical package for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Meta-analysis was performed to further investigate the association of ACE D allele with longevity in European populations using Stata 10 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The odds ratio (OR) was used to compare contrasts of alleles between general population and senescents. Data were combined using random effects method (Mantel-Haenszel) and fixed effects method (Der Simonian and Laird). The between-population heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ2-based Cochran’s Q statistic (Petiti 1994) and the inconsistency index (I2; Higgins et al. 2003). Publication bias or other small study related bias was evaluated using the rank correlation method of Begg and Mazumdar and fixed effects regression method of Egger et al. (1997).

To identify potential influential studies (countries), we calculated the effects estimates (ORs) by removing an individual study each time and then checked if the overall significance of the estimate or of the heterogeneity statistics was altered. Due to the composite nature of each country’s sample, cumulative and meta-regression analysis could not be assesed.

Results

The examined CVD risk factors are shown in Table 2. Women had significantly elevated total cholesterol (p < 0.000), LDL cholesterol (p < 0.000), and triglyceride level (p < 0.001) compared to men. The majority of the subjects were hypertensive, although the average BP was normal (below 140/90 mmHG), indicating adequate medical treatment. In Table 3, we compared the distribution of CVD risk factors in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Hypertensives were more likely to be younger (87.55 vs. 88.65 years) and to have elevated HDL cholesterol (p < 0.03).

Table 2.

Basic description of distribution of CVD risk factors among Croatian elderly subjects (80–101 years)

| Variable | Gender | N | Mean/prevalence | SD | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Male | 80 | 88.1 | 3.4 | 0.536 |

| Female | 221 | 88.4 | 3.7 | ||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | Male | 80 | 138.2 | 23.8 | 0.653 |

| Female | 221 | 132.6 | 22.8 | ||

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | Male | 80 | 73.7 | 11.7 | 0.431 |

| Female | 221 | 70.0 | 11.6 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Male | 80 | 27.6 | 4.8 | 0.450 |

| Female | 221 | 27.5 | 4.4 | ||

| Total cholesterol (>5.0 mmol/l) | Male | 33 | 41.2% | 0.000 | |

| Female | 161 | 72.8% | |||

| HDL cholesterol (F < 1.20; M < 1.0) | Male | 17 | 21.2% | 0.298 | |

| Female | 55 | 24.8% | |||

| LDL cholesterol (>3.0 mmol/l) | Male | 35 | 43.7% | 0.000 | |

| Female | 150 | 67.8% | |||

| Triglycerides (>1.70 mmol/l) | Male | 18 | 22.5% | 0.001 | |

| Female | 97 | 43.8% |

Differences between sexes were tested using Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables (cut-off values are listed in parenthesis)

Table 3.

Differences in CVD risk factors mean values in normotensives (NT) and hypertensives (HT) tested using independent samples t test

| Variable | HT status | N | Mean | SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | NT | 51 | 88.65 | 4.10 | 0.042 |

| HT | 250 | 87.55 | 3.35 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | NT | 45 | 27.38 | 4.24 | 0.321 |

| HT | 234 | 28.11 | 4.61 | ||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | NT | 51 | 5.87 | 4.06 | 0.522 |

| HT | 248 | 5.50 | 1.13 | ||

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | NT | 51 | 1.28 | 0.35 | 0.039 |

| HT | 248 | 1.39 | 0.35 | ||

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | NT | 50 | 3.23 | 0.84 | 0.290 |

| HT | 248 | 3.38 | 0.96 | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | NT | 51 | 1.83 | 1.61 | 0.146 |

| HT | 248 | 1.60 | 0.86 |

Of the investigated risk factors, multivariate logistic regression showed that age (younger olds, 80–90 years), female sex (OR = 3.13: 95% CI = 1.59–6.19), and elevated triglyceride concentration (OR = 2,53: 95% CI = 1.29–4.95) had significant influence on incidence of HT, while ACE genotype, BMI, waist/hip ratio, and cholesterol concentration did not (Table 4).

Table 4.

CVD risk factors in multivariate logistic analysis for the hypertension

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE I/D | ID versus II | 1.04 | 0.46–2.42 | |

| DD versus II | 1.04 | 0.44–2.45 | ||

| Age (younger olds are referent) | 0.90 | 0.82–0.98 | * | |

| Sex (males are referent) | 3.13 | 1.59–6.19 | ** | |

| Triglycerides (<1.70 mmol/l is referent) | 2.53 | 1.29–4.95 | *** | |

The best model included ACE I/D genotypes, age (younger olds, 80–90 years, and older olds, ≥91 years), sex, and triglyceride blood concentration (<1.70 mmol/l and ≥1.70 mmol/l)

*p = 0.01; **p = 0.001; ***p = 0.006

In order to test the association between ACE I/D polymorphism and longevity, we used previously reported frequencies for the general Croatian population (Barbalić et al. 2004). The genotype distribution in general population was compatible with HWE, but it was not the case in 80+ years population where we found a lack of heterozygotes (p = 0.000061, df = 1). The ACE genotype (II, ID, and DD) distribution differed significantly between two age cohorts with DD genotype being twice as frequent in senescents as in the younger cohort. D allele frequency was also higher in elderlies (Table 5). Both ACE I/D genotype (p < 0.00001) and allele (p < 0.001) distribution differences between general and 80+ population were statistically significant. The ACE genotype and allele distributions were not significantly different between our NT and HT senescent groups (p > 0.05).

Table 5.

ACE I/D genotype and allele frequencies in general and elderly (80–101 years) Croatian population

| Genotype distribution | Allele frequency | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DD | ID | II | D | I | |||

| Croatia — general (n = 172) | N | 38 | 94 | 40 | 170 | 174 | 344 |

| % | 22.1 | 54.7 | 23.3 | 49.4 | 50.6 | 100 | |

| Croatia — elderly (n = 301) | N | 129 | 110 | 62 | 368 | 234 | 602 |

| % | 42.8 | 36.5 | 20.5 | 61.1 | 38.9 | 100 | |

| χ2 = 22.045, df = 2 | χ2 = 12.304, df = 1 | ||||||

| p < 0.00001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

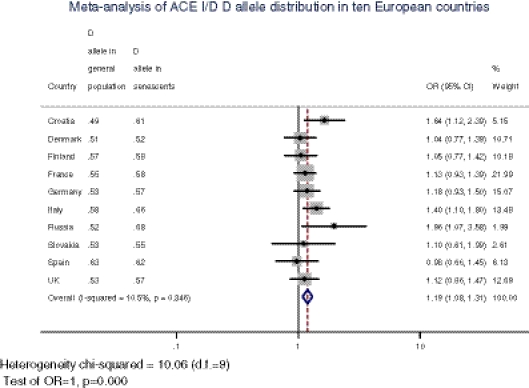

The results of the meta-analysis are presented in Fig. 1. In nine of ten analyzed countries (with the exception of Spain), D allele frequencies were higher in elderlies than in general population; individual ORs were statistically significant as well as the total OR amounting 1.19 (95% CI, 1.08–1.31; Fig. 1). Since the Cochrane Q test result indicated that the heterogeneity was low (I2 < 11%, p = 0.346), the data were pooled by means of the fixed effect model (Mantel–Haenszel method).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot displaying results of the fixed effects meta-analysis of ACE D allele distribution in two age cohorts of ten European countries on a logarithmic scale. Each country data include D allele frequencies in general population and elderlies, partial and overall odds ratios (ORs), and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as well as a contribution of each sample to the overall OR. The overall pooled OR is 1.19 (95% CI, 1.08–1.31, p = 0.0003). Horizontal line on forest plot represents a 95% CI for each study, and the size of the square corresponds to the weight of the study in the meta-analysis. The solid vertical line shows an OR of 1, and the dashed vertical line corresponds to the overall OR of the sample

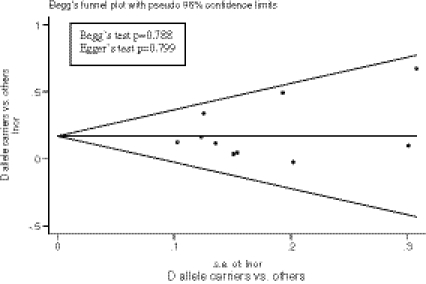

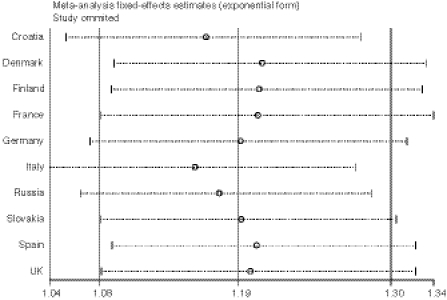

Using Begg’s (p > 0.788) and Egger’s test (p > 0.799) as well as by visual inspection of the funnel plot (Fig. 2), we found no evidence for publication bias. The influential analysis revealed that no single study (country) was responsible for the overall significance of the estimates (Fig. 3). After removing an individual study each time and recalculating the combined estimates, the overall estimates as well as the heterogeneity statistics remained nearly unchanged. For the includued studies performed by the same research group, we examined the materials and methods sections and assured that these studies contained no overlapping sets of individuals.

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot for the results of meta-analysis of D allele carriers compared to others (non-carriers). The symmetry of the plot indicates no publication or other small studies related bias. The results of the two formal tests for detecting such bias are listed

Fig. 3.

Influential meta-analysis plot with the effects estimates (ORs) after omiting an individual study each time

Discussion

Numerous worldwide conducted studies have demonstrated that elevated BP is one of the major risk factors for developing cardiovascular diseases. However, only few have tested the association between candidate genes and CVD risk factors in elderly cohort. This study provides information on the ACE I/D polymorphism, HT, dislypidemia, and BMI in Croatian elderly population. We did not confirm previously reported role of the investigated risk factors to the development of HT in our 80+ years cohort. Probably the most remarkable finding from this study is a detection of significantly more D allele carriers among elderlies than in general population, suggesting that ACE D allele contributes to good health and longevity.

The prevalence of HT in our 80+ subjects was thrice as high as the prevalence in Croatian general population 18–64 years (First Croatian Health Project; Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia 1995). It was also higher compared to hypertensives in the elderly Croatian population aged 65–80 years (83% vs. 63%; Škarić-Jurić et al. 2006). The NHANES data, a USA 30-year longitudinal study, presented the growth of prevalence of HT in adults across the age spectrum; 27.3% among participants younger than 60 years of age, 63.0% in those aged 60 to 79 years, and 74.0% in those aged 80 years or older (Lloyd-Jones et al. 2005). These findings are in concordance with pathophysiological changes that occur in the cardiovascular system with aging: decreasing elasticity of the aorta and great arteries, a dropout of myocytes that together with the increased left ventricular (LV) afterload results in modest LV hypertrophy, apoptosis of atrial pacemaker cells, and HT as a consequence of all that (Yin et al. 1982; Vaitkevicius et al. 1993; Cheitlin and Zipes 2001). However, some observations have shown that BP level is closely related to the risk of stroke and heart disease, but the association declines with increasing age (Prospective Studies Collaboration 1995). Considering our finding that HT is more prevalent in women than in men, it is not a surprise that in women, we also detected significantly elevated biochemical risk factors for CVD: total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride level.

Logistic regression of risk factors for HT showed statistically significant contribution of female sex, triglyceride concentration, and age (younger elderlies, <91 years) to the prevalence of HT. The higher prevalence of HT in women than in men in our study is consistent with the results of Martins et al. (2001), where he concluded that women have higher rates of HT than men as they age. The prevalence of CVD in women is low during the reproductive years and after menopause women’s risk rises from two to three times. Carlson et al. (2004) reported that a decrease in estrogen production leads to the development of atherosclerosis. In a recent review, Labreuche et al. (2010) found a positive association between elevated triglyceride levels and stroke and carotid atherosclerosis.

The role of the ACE gene in the pathogenesis of HT is well known and documented (Jeunemaitre et al. 1992a), yet many ACE I/D genotype distribution results in hypertensive vs. nonhypertensive subjects are contradictory (Szadkowska et al. 2006; Freitas et al. 2007; Miyama et al. 2007). Some explain this inconsistency with genetic and environmental heterogeneity between different ethnic groups (Bautista et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2007; Higaki et al. 2000; Jiménez et al. 2007; Companioni Nápoles et al. 2007) as well as ACE I/D polymorphism gene’s complex interaction with other genetic factors that contribute to the expression of HT (Nawaz and Hasnain 2008).

Previously reported results pointed to the association of ACE D polymorphism with HT in general Croatian population (Barbalić et al. 2006), while in 80+ years population, we did not confirm it. Our findings do not support population-specific, but age-conditioned association of ACE I/D genotype with HT.

The first study of ACE I/D genotype distribution within centenarians and controls, conducted by Schachter et al. (1994), reported unexpectedly frequent occurrence of DD genotype in the French centenarians compared with the control group (40% vs. 26%, p = 0.01). The experiment was repeated in 2000 with nearly twice that sample, but the results failed to confirm previous findings (Blanche et al. 2001). Neither the Rotterdam study results (Arias-Vasquez et al. 2005) nor the results of the Italian study (Nacmias et al. 2007) suggested any relation of ACE I/D polymorphism with longevity. Then again, Lufts group observed that in German population over 80 years, D allele occurred at higher frequency than in youngs (Luft 1999).

Considering widely investigated role of ACE I/D polymorphism in various diseases, namely, CVD, Alzheimer’s disease, sarcoidosis, and others, allele frequencies are reported in numerous studies for different age groups. Since the said longevity studies results were inconclusive, we conducted a meta-analysis in both healthy general and 80+ European populations. In the analysis, we included subjects that represented healthy controls for D allele frequencies in various diseases, as well as the subjects from previously mentioned longevity studies. It is possible that some relevant studies were not included in our review, as we limited our search to reports published in English. With the only exception of Spain, the results from all available countries were similar to ours; ACE gene D allele frequencies were higher in subjects 80+ years than in general adult population.

Schahter’s group proposed that the risk of developing CVD conferred by the D allele is redeemed by a possible long-term protective effect; such an effect may give some early selective advantage and/or a late reversal of its negative survival influence. They also suggested a potential relation of protective effect of DD genotype to other biological functions of ACE besides in RAS and kinin–kallikrein systems: neuroendocrine and immunomodulator functions related to ACE levels may contribute to overall survival and longevity (Ehlers and Riordan 1989; McGeer and Singh 1992; Costerousse et al. 1993). The association of DD genotype with longevity may also be derived from linkage disequilibrium to a closely mapping gene still to be identified. In addition, it is interesting to mention that a gene encoding for the human growth hormone also maps to chromosome 17q23, shows strong linkage to ACE, and appears to have an important role in senescence (McGeer and Singh 1992; Crisan and Carr 2000; Huang et al. 2007).

Comparing centenarians and middle-aged controls from Italy, France, and Denmark, Panza et al. (2003) reported a decrease, although statistically insignificant, in ACE I allele frequencies from North to South of Europe in both age groups. In 2004, Barbalić graphically presented the worldwide frequency distribution of ACE Alu insertion, where she reported lowest frequency of I allele in Africa, which increases toward Asia and Australia on one side and the Americas on the other with general Croatian population frequency of 50.06% falling within the range of European populations. We found no geographical gradient of ACE D allele in our meta-analysis, neither in general nor in 80+ populations.

In conclusion, we presented in this study that the ACE D allele was not associated with HT in Croatian senescent population, regardless of its well-known role in BP regulation and direct impact at CVD development. ACE DD genotype and D allele frequency were more frequent among the senescents than in general Croatian population. Such genetic differences, which were confirmed with meta-analysis including other European populations, indicate that D allele, apart from being CVD risk factor in middle–aged population, might have some, yet unrecognized, advantageous role in successful human aging.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science, Education, and Sports of the Republic of Croatia 196-1962766-2747 to N. Smolej Narančić. We would like to thank the study participants and the administration, medical teams, and employees of the homes for elderly and infirm. We are also grateful to Professor Daniela Sivakova for providing us raw data from 80+ years Slovakian population. We also appreciate help from our colleagues and friends, Professor Branka Janićijević and Ana Barešić, PhD student, in collecting field data.

References

- Agerholm-Larsen B, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Frikke-Schmidt R, et al. ACE gene polymorphism as a risk factor for ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agerholm-Larsen B, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. ACE gene polymorphism in cardiovascular disease: meta-analyses of small and large studies in whites. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:484–492. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.2.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alía P, Mañá J, Capdevila O, et al. Association between ACE gene I/D polymorphism and clinical presentation and prognosis of sarcoidosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2005;65(8):691–698. doi: 10.1080/00365510500354128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez R, Alvarez V, Lahoz CH, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme and endothelial nitric oxide synthase DNA polymorphisms and late onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:733–736. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbustini E, Grasso M, Fasani R, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme gene deletion allele is independently and strongly associated with coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995;74:584–591. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.6.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Vasquez A, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Schut AF, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme gene, smoking and mortality in a population-based study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005;35:444–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbalić M, Peričić M, Škarić-Jurić T, Smolej Narančić N. ACE Alu insertion polymorphism in Croatia and its isolates. Coll Antropol. 2004;28:603–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbalić M, Škarić-Jurić T, Cambien F, et al. Gene polymorphisms of the renin–angiotensin system and early development of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(8):837–842. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista LE, Ardila ME, Gamarra G, Vargas CI, Arenas IA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism and risk of myocardial infarction in Colombia. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(8):473–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benigni A, Cassis P, Remuzzi G. Angiotensin II revisited: new roles in inflammation, immunology and aging. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:247–257. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bladbjerg EM, Andersen-Ranberg K, Maat MP, et al. Longevity is independent of common variations in genes associated with cardiovascular risk. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1100–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanche H, Cabanne L, Sahbatou M, Thomas G. A study of French centenarians: are ACE and APOE associated with longevity? C R Acad Sci III. 2001;324:129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0764-4469(00)01274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster UC, Perazella MA. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and the kidney: effects on kidney disease. Am J Med. 2004;116:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busjahn A, Knoblauch J, Knoblauch M, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme and angiotensinogen gene polymorphisms, plasma levels, and left ventricular size: a twin study. Hypertension. 1997;29:165–170. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambien F, Poirier O, Lecerf L, et al. Deletion polymorphism in the gene for angiotensin-converting-enzyme is a potent risk factor for myocardial infarction. Nature. 1992;359:641–644. doi: 10.1038/359641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KJ, Eisenstat SA, Ziporyn T. The new Harvard guide to women’s health. Boston: Harvard University; 2004. pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cheitlin MD, Zipes DP. Cardiovascular disease in the elderly. In: Braunwald E, Zipes DP, Libby P, editors. Heart disease. 6. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001. p. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Emberson J, Fletcher A, et al. Life expectancy in relation to cardiovascular risk factors: 38 year follow-up of 19 000 men in the Whitehall study. BMJ. 2009;339:3513–3521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Companioni Nápoles O, Sautié Castellanos M, Leal L, et al. ACE I/D polymorphism study in a Cuban hypertensive population. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;378:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbo RM, Ulizzi L, Piombo L, Scacchi R. Study on a possible effect of four longevity candidate genes (ACE, PON1, PPAR-c, and APOE) on human fertility. Biogerontology. 2008;9:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerousse O, Allegrini J, Lopez M, Alhenc-Gelas F. Angiotensin I converting enzyme in human circulating mononuclear cells: genetic polymorphism of expression in T-lymphocytes. Biochem J. 1993;290:33–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2900033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan D, Carr J. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme: genotype and disease associations. J Mol Diagn. 2000;2:105–115. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census 1991. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dankova Z, Sivakova D, Luptakova L, Blazicek P. Association of ACE (I/D) polymorphism with metabolic syndrome and hypertension in two ethnic groups in Slovakia. Anthropol Anz. 2009;67(3):305–316. doi: 10.1127/0003-5548/2009/0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh EM, Inserra F, Ferder M, Ferder L. From mitochondria to disease: role of the renin–angiotensin system. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:545–553. doi: 10.1159/000107757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale P, Cannizzaro S, Paterna S. Does angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism affect blood pressure? Findings after 6 years of follow-up in healthy subjects. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikmen M, Günes HV, Degirmenci I, Özdemir G, Basaran A. Are the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and activity risk factors for stroke? Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64(2):212–216. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2006000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolgikh MM, Voevoda MI, Malyutina SK (2001) Age change of ACE gene genotypes and alleles frequencies in urban population of West Siberia. First workshop on information technologies application to problems of biodiversity and dynamics of ecosystems in North Eurasia (WITA-2001), Book of abstracts

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers MRW, Riordan JF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme: new concepts concerning its biological role. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5311–5313. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I. Signaling by the angiotensin-converting enzyme. Circ Res. 2006;98:887–896. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000217340.40936.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas SRS, Cabello PH, Moura-Neto RS, Dolinsky LC, Bóia MN. Combined Analysis of genetic and environmental factors on essential hypertension in a Brazilian rural population in the Amazon Region. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;88:393–397. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes RM, Perola M, Nissinen A, Tuomilehto J. ACE gene and physical activity, blood pressure and hypertension: a population study in Finland. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2508–2512. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01196.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky D, Tysoe C, Brayne CE, et al. Analysis of the apo E/apo C-I, angiotensin converting enzyme and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genes as candidates affecting human longevity. Atherosclerosis. 1997;129:177–183. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(96)06027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrib A, Zhou W, Sherwood R, Peters T. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene polymorphism in patients with sarcoidosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:137. doi: 10.1042/bst026s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjadj S, Tarnow L, Forsblom C, et al. Association between angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphisms and diabetic nephropathy: case-control, haplotype, and family-based study in three European populations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1284–1291. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Ortega E, Medina Fernández-Aceituno A, Rodríguez-Esparragón FJ, et al. The involvement of the renin–angiotension system gene polymorphisms in coronary heart disease. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55:92–99. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(02)76567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki J, Baba S, Katsuya T, et al. Deletion allele of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene in creases risk of essential hypertension in Japanese men: the Suita study. Circulation. 2000;101:2060–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Chen XH, Payne JR, et al. Haplotype of growth hormone and angiotensin I-converting enzyme genes, serum angiotensin I-converting enzyme and ventricular growth: pathway inference in pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17(4):291–294. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000239976.54217.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MS, Lehtimäki T, Juonala M, et al. Polymorphism of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and angiotesinogen (AGT) genes and their associations with blood pressure and carotid artery intima media thickness among healthy Finnish young adults—the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A, Brown K, Langdown J, et al. Effect of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene deletion polymorphism on the risk of venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:562–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, et al. Molecular basis of human hypertension: role of angiotensinogen. Cell. 1992;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeunemaitre X, Lifton RP, Hunt SC, Williams RR, Lalouel JM. Absence of linkage between the angiotensin converting enzyme locus and human essential hypertension. Nat Genet. 1992;1:72–75. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeunemaitre X, Inoue I, Williams C, et al. Haplotypes of angiotensinogen in essential hypertension. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;51:1448–1460. doi: 10.1086/515452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez PM, Conde C, Casanegra A, et al. Association of ACE genotype and predominantly diastolic hypertension: a preliminary study. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2007;8:42–44. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2007.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaydjieva L, Perez-Lezaun A, Angelicheva D, et al. A founder mutation in the GK1 gene is responsible for galactokinase deficiency in Roma (gypsies) Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(5):1299–1307. doi: 10.1086/302611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keavney BD, Dudley CR, Stratton IM, et al. UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS) 14: association of angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism with myocardial infarction in NIDDM. Diabetologia. 1995;38(8):948–952. doi: 10.1007/BF00400584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe PG, Russ C, McIlory S, et al. Variation in DCP1, encoding ACE, is associated with susceptibility to Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet. 1999;21:71–72. doi: 10.1038/5009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama H, Maeshima Y, Takazawa Y, et al. Regulation of angiogenic factors in angiotensin II infusion model in association with tubulointerstitial injuries. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labreuche J, Deplanque D, Touboul PJ, Bruckert E, Amarenco P. Association between change in plasma triglyceride levels and risk of stroke and carotid atherosclerosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindpaintner K, Pfeffer MA, Kreutz R, et al. A prospective evaluation of an angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphism and the risk of ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:706–711. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D. Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum: current outcomes and control in the ommunity. JAMA. 2005;294(4):466–472. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft FC. Bad genes, good people, association, linkage, longevity and the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26(7):576–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marre M, Jeunemaitre X, Gallois Y, et al. Contribution of genetic polymorphism in the renin–angiotensin system to the development of renal complications in insulin-dependent diabetes: Genetique de la Nephropathie Diabetique (GENEDIAB) study group. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(7):1585–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins D, Nelson K, Pan D, Tareen N, Norris K (2001) The effect of gender on age-related blood pressure changes and the prevalence of isolated systolic hypertension among older adults: data from NHANES III. J Gend Specif Med 4(3):10–13, 20 [PubMed]

- McGeer EG, Singh EA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme in cortical tissue in Alzheimer’s and some other neurological diseases. Dementia. 1992;3:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miloserdova OV, Slominsky PA, Limborska SA. Age-dependent variation of the allele and genotype frequencies in insertion–deletion polymorphism for the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene. Genetika. 2001;38(1):87–89. [Google Scholar]

- First Croatian health project: final report. Zagreb: Ministry of Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miyama N, Hasegawa Y, Suzuki M, et al. Investigation of major genetic polymorphisms in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in subjects with young-onset hypertension selected by a tar geted-screening system at university. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2007;29:61–67. doi: 10.1080/10641960601096968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondry A, Loh M, Pengbo L, Zhu AL, Nagel M. Polymorphisms of the insertion/deletion ACE and M235T AGT genes and hypertension: surprising new findings and meta-analysis of data. BMC Nephrol. 2005;6:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllykangas L, Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: a genetic association study in a population aged 85 or over. Neurosci Lett. 2000;292:195–198. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacmias B, Bagnoli S, Tedde A, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism in sporadic and familial Alzheimers disease and longevity. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz SK, Hasnain S. Pleiotropic effects of ACE polymorphism. Biochemia Med. 2008;19(1):36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarov IB, Woods DR, Montgomery HE, et al. The angiotensin converting enzyme I/D polymorphism in Russian athletes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:797–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza F, Solfrizzi V, D’Introno A, et al. Angiotensin I converting enzyme (ACE) gene polymorphism in centenarians: different allele frequencies between the North and South of Europe. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(03)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolisso G, Tagliamonte MR, Lucia D, et al. ACE gene polymorphism and insulin action in older subjects and healthy centenarians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:610–614. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos KI, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) gene polymorphism in sarcoidosis in relation to associated autoimmune diseases. J Intern Med. 2000;247:71–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterna S, Pasquale P, D’Angelo A, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene deletion polymorphism determines an increase in frequency of migraine attacks in patients suffering from migraine without aura. Eur Neurol. 2000;43(3):133–136. doi: 10.1159/000008151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petiti DB (1994) Meta-analysis decision analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis, Oxford University Press

- Platten M, Youssef S, Hur EM, et al. Blocking angiotensin-converting enzyme induces potent regulatory T cells and modulates TH1- and TH17-mediated autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14948–14953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903958106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospective Studies Collaboration Cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure and stroke: 13000 strokes in 450000 people in 45 prospective cohorts. Lancet. 1995;346:1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92836-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo ME, Gonzalez W, Nicoletti A, et al. Angiotensin stimulates endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 via nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by intracellular oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:645–651. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard F, Fromentin-David I, Ricolfi F, et al. The angiotensin I converting enzyme gene as a susceptibility factor for dementia. Neurology. 2001;56:1593–1595. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riera-Fortuny C, Real JT, Chaves FJ, et al. The relation between obesity, abdominal fat deposit and the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene I/D polymorphism and its association with coronary heart disease. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2005;29:78–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigat B, Hubert C, Alhenc-Gelas F, et al. An insertion/deletion polymorphism in the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene accounting for half the variance of serum enzyme levels. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1343–1346. doi: 10.1172/JCI114844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani NJ, O’Toole L, Martin D, et al. Insertion/deletion polymorphism in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and risk of and prognosis after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Duijn CM, Witteman JC. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphism and carotid artery wall thickness: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2003;34:1634–1639. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000077926.49330.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter F, Faure-Delanef L, Guenot F, et al. Genetic associations with human longevity at the APOE and ACE loci. Nat Genet. 1994;6:29–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunkert H, Hense H-W, Holmer S-R, et al. Association between a deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin converting enzyme gene and left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1634–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P. Meta-analysis of the ACE gene in ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:227–230. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Smith I, Maguire G, Stewart S, Shneerson J, Brown MJ (1997) Clinical value of ACE genotyping in diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Lancet 349:1602–1603 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sivakova D, Lajdova A, Basistova Z, Cvicelova Z, Blazicek P. ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism and its relationships to the components of metabolic syndrome in elderly Slovaks. Anthropol Anz. 2009;67(1):1–11. doi: 10.1127/0003-5548/2009/0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Škarić-Jurić T, Smolej Narančić N, Barbalić M, et al. (2006) Distribucija čimbenika rizika za kardiovaskularne bolesti u osoba starijih od 65 godina u Republici Hrvatskoj. In: Anic B, Tomek-Roksandic S (Eds.), 2nd Croatian gerontolological congress with international participation: book of abstracts. Liječnički vjesnik 128(1):64–65

- Staessen JA, Wang JG, Ginocchio G, et al. The deletion/insertion polymorphism of the angiotensin converting enzyme gene and cardiovascular-renal risk. J Hypertens. 1997;15:1579–1592. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, et al. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:881–900. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szadkowska A, Pietrzak I, Klich I, et al. Polymorphism I/D of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and disturbance of blood pressure in type 1 diabetic children and adolescents. Przegl Lek. 2006;63:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisi-Raygani A, Ghaneialvar H, Rahimi Z, et al. The angiotensin converting enzyme D allele is an independent risk factor for early onset coronary artery disease. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitkevicius PV, Fleg JL, Engel JH, et al. Effects of age and aerobic capacity on arterial stiffness in healthy adults. Circulation. 1993;88:1456–1462. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J, Flores C, Pérez-Méndez L, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is not associated with susceptibility and outcome in sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:488–495. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0937-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JS, Lourie JA. Practical human biology (International biological programme handbook No. 9) London: Academic; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 894. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Li J, Sheng W, Liu L. Meta-analysis of genetic studies from journals published in China of ischemic stroke in the Han Chinese population. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26(1):48–62. doi: 10.1159/000135653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin FCP, Spurgeon HA, Rakusan K, Weisfeldt ML, Lakatta EG. Use of tibial length to quantify cardiac hypertrophy: application in the aging rat. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:941–947. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.6.H941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YL, Zhou SX, Lei J, Zhang JM. Association of angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene polymorphism with ACE and PAI-1 levels in Guangdong Chinese Han patients with essential hypertension. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27(11):1681–1684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]