Abstract

We studied prospectively the midlife handgrip strength, living habits, and parents’ longevity as predictors of length of life up to becoming a centenarian. The participants were 2,239 men from the Honolulu Heart Program/Honolulu–Asia Aging Study who were born before the end of June 1909 and who took part in baseline physical assessment in 1965–1968, when they were 56–68 years old. Deaths were followed until the end of June 2009 for 44 years with complete ascertainment. Longevity was categorized as centenarian (≥100 years, n = 47), nonagenarian (90–99 years, n = 545), octogenarian (80–89 years, n = 847), and ≤79 years (n = 801, reference). The average survival after baseline was 20.8 years (SD = 9.62). Compared with people who died at the age of ≤79 years, centenarians belonged 2.5 times (odds ratio (OR) = 2.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.23–5.10) more often to the highest third of grip strength in midlife, were never smokers (OR = 5.75 95% CI = 3.06–10.80), had participated in physical activity outside work (OR = 1.13 per daily hour, 95% CI = 1.02–1.25), and had a long-lived mother (≥80 vs. ≤60 years, OR = 2.3, 95% CI = 1.06–5.01). Associations for nonagenarians and octogenarians were parallel, but weaker. Multivariate modeling showed that mother’s longevity and offspring’s grip strength operated through the same or overlapping pathway to longevity. High midlife grip strength and long-lived mother may indicate resilience to aging, which, combined with healthy lifestyle, increases the probability of extreme longevity.

Keywords: Aging, Longevity, Inter-generational, Grip strength, Mortality, Human

Introduction

Recently, a study showed that those who survived 100 years needed less hospital care at a given age than their shorter lived contemporaries (Engberg et al. 2009), supporting centenarians as a model for healthy aging. Thus far, centenarian phenotype has been described, but studies have mostly been cross-sectional (Willcox et al. 2006a). Knowledge on early physiological predictors of exceptional longevity in humans is lacking. An appropriate approach to study predictors of human longevity is to follow a representative cohort of people studied earlier in life until their death, including cohort members who died at any age as well as long-lived groups of interest.

Long-lived people may have physiological reserve, which may be observed already in youth or midlife and which makes them less vulnerable to diseases, disability, and mortality in old age. Handgrip strength is a widely used measure of total body strength and a marker of physiological reserve during aging, with good strength protecting from disability and mortality (Rantanen et al. 1999, 2000). Handgrip strength declines at an approximate annual rate of 1% after midlife and may be a good biomarker of aging (Rantanen et al. 1998). Grip strength likely reflects the combined influences of genetic predisposition, acquired modifications of physical constitution, aging processes, and chronic diseases (Rantanen et al. 2003). Part of individual differences in handgrip strength may be explained by genetic and environmental factors also influencing aging and longevity (Rantanen et al. 2003). Genetic factors underlie 14–60% of individual differences in grip strength (Reed et al. 1991; Frederiksen et al. 2002; Tiainen et al. 2004; Silventoinen et al. 2008). Heritability of longevity ranges from 10% to 50% (Herskind et al. 1996; Mitchell et al. 2001; Yashin et al. 2000; Kenyon 2010). It is possible that there is overlap in genetic influences underlying grip strength and mortality. This is indirectly supported by studies showing that offspring of long-lived parents had, in their later life, better handgrip strength and less chronic diseases than offspring of parents with average life span (Frederiksen et al. 2002).

In addition to poor health and higher age per se, other well-known risk factors that strongly influence human mortality include physical activity (Hakim et al. 1988; Carlsson et al. 2007; Senchina and Kohut 2007; Nicklas et al. 2008; Autenrieth et al. 2009), smoking (Curb et al. 1990; Ferrucci et al. 1999), socioeconomic position (Rask et al. 2009), and social integration (Rask et al. 2009; Ford et al. 2006). These factors correlate with survival risk at least partly through their influence on biological processes influencing aging, such as inflammation, and risk for chronic age-related diseases (Jylhä et al. 2007; Kaptoge et al. 2010; Loucks et al. 2006; Willcox et al. 2006b).

We studied grip strength measured at the age of 56–68 years as a predictor of remaining length of life up to centenarian years among men born 1900–1909. We also assessed whether longevity of parents, smoking, and physical activity correlate with length of life and examined the possible role of these factors in underlying the association of grip strength with longevity.

Cohort

The participants are from the Honolulu Heart Program/Honolulu–Asia Aging Study which began in 1965. Briefly, the World War II Selective Service Registration file was used to identify 12,417 possibly eligible men of Japanese ancestry born from 1900 to 1919 and living on Oahu. In 1965–1968, 8,006 men participated in Exam 1. Of them, 2,239 were included in the current study based on birth date of June 1909 or earlier. Thus, at least 100 years had passed since the birth of all participants by June 2009, when the vital status was last updated. The accuracy of the birth year in the database was 99.9% when contrasted against social security information. At the baseline, the average age of participants was 62 years (range 56–68). Mortality records were collected from the beginning of the study based upon a review of newspaper obituaries and listings of death certificates filed with the Hawaii State Department of Health. Survival time was calculated as the time between Exam 1 and the date of death. In the analyses of survival times, the death dates for the surviving 13 centenarians were replaced with the date at the end of the surveillance. For further analyses, the participants were categorized into four groups based on their longevity: ≤79 years (reference), 80–89 years (octogenarian), 90–99 years (nonagenarian), and 100 or more years (centenarian).

All procedures of the study were in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kuakini Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants or family representatives if participants were unable to provide consent.

Predictors

Handgrip strength was measured using the Smedley Hand Dynamometer (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). While sitting, participant extended his arm in front of him on the table and gripped the dynamometer. If necessary, the tester held the dynamometer steady. The width of the handle was adjusted so that the second phalanx was against the inner stirrup. Three trials, with brief pauses, were allowed for each hand alternately. Subjects were encouraged to exert their maximal grip. The best result was chosen for analyses. In all analyses, grip strength was adjusted for height, weight, and age at Exam 1. Body weight and height were measured directly and expressed as kilograms and centimeters, respectively.

Socioeconomic status at Exam 1 was described on the basis of level of education (1 = primary school or less; 2 = junior or senior high school; 3 = technical school or university) and usual occupation (1 = physically heavy work, unskilled, semiskilled, skilled or farming; 2 = light work, sales or clerical, managerial, professional). Marital status was categorized as married vs. never married, widowed or divorced. The participants were asked about how many hours they spent in a day doing heavy activity outside work such as shoveling or digging or moderate activity such as gardening or carpentry. The hours were summed up to describe the physical activity level during leisure. Smoking status was categorized as follows: 1 = never smoked; 2 = former or current smoker. Pack years of smoking were calculated based on the number of cigarettes smoked per day and years smoked.

Age of mother and father was self-reported at Exam1 and at Exam 4 (1991–1992). The age at death remained uncertain for 251 mothers and 64 fathers. For them, their reported age at Exam 1 or 4 was used in the analyses. Excluding these people did not materially change the results. For logistic regression analyses, we categorized mother’s age as follows: 60 years or less, 61–79 years, and 80 years and older. There were 324 participants whose mother was dead at Exam 1 and who had again reported her age at death at Exam 4, 25 years later. The intra-class correlation (ICC) between these two measures was 0.876. For father’s longevity, the ICC was 0.907 (n = 413). Reported parental longevity was not biased as the correlation between birth year of the participant and mother’s (r = 0.02, p > 0.05) or father’s age (r = 0.014, p > 0.05) was practically zero.

Information about prevalent chronic conditions was collected based on self-reports and clinical health examination at Exam 1. Data on present vs. absent diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure (140/100 mmHg), heart attack, angina pectoris, other heart disease, and gout are analyzed here.

Analyses

General linear models were used to compare survival times between categories of baseline predictors and to compare baseline predictors as continuous variables between longevity groups. Potential confounders such as baseline age were added into the models as covariates and marginal means were reported. Disease prevalence and other categorical baseline variables were compared between longevity groups by cross-tabulation. Logistic regression models were used to assess the odds of becoming a centenarian (case) vs. dying at the age of 79 years or earlier (control) in tertiles of baseline grip strength and other predictor categories. The odds for surviving to become a nonagenarian or octogenarian were computed similarly. Several multiple logistic regression models were constructed to examine whether the other baseline predictors would explain the potential effect of grip strength on becoming a centenarian when compared with those who died at the age of 79 or earlier. First, each variable was added to the model one at a time, and the changes in the odds of highest vs. lowest and middle vs. lowest grip strength tertile were observed. Finally, all variables were included in the model.

Results

Of the 2,239 participants who had been born at least 100 years ago, 2,226 participants (99.4%) had died and their length of life was determined. Altogether, 47 people became centenarians. The average length of survival after baseline was 20.8 years (SD = 9.62) and mean length of life was 82.4 years (SD = 9.4). The age at baseline (62.0 years, SE = 0.60, range 56–68), educational background (primary school or less 13%, junior or senior high school 75%, technical school or university 12%) or type of work (heavy 21% or light 79%) did not differ according to longevity. In midlife, the proportions of never married, separated, or widowed men were 13% for those who lived ≤79 years, 8% for 80–89 years, 9% for 90–99 years, and 8% for centenarians (p = 0.005).

A significant gradient of higher handgrip strength and daily hours in physical activity were observed for increasing longevity (Table 1). The proportion of never smokers from lowest to highest longevity category was 24% for those who died at the age of ≤79 years, 31% for octogenarians, 41% for nonagenarians, and 65% for centenarians (p < 0.001). Long-lived men had more often long-lived mothers than men with shorter lives, but fathers’ longevity did not correlate with sons’ longevity. Even though the total prevalence of chronic conditions at baseline was low, a statistically significant declining trend for baseline chronic conditions was observed for increasing longevity (Table 2). The most common chronic conditions were diabetes and high blood pressure.

Table 1.

Differences in baseline characteristics according to longevity

| Longevity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −79 years (n = 801) | 80–89 years (n = 846) | 90–99 years (n = 545) | 100+ years (n = 47) | |||||||

| Baseline characteristics | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | F | p |

| Baseline age (years) | 61.9 | 0.100 | 62.2 | 0.097 | 62.0 | 0.121 | 62.3 | 0.414 | 1.12 | 0.339 |

| Height (cm)a | 159.9 | 0.201 | 159.8 | 0.195 | 159.1 | 0.024 | 158.1 | 0.820 | 3.50 | 0.015 |

| Weight (kg)b | 61.1 | 0.272 | 60.9 | 0.263 | 60.6 | 0.330 | 59.9 | 1.105 | 0.66 | 0.576 |

| Grip strength (kg)c | 34.5 | 0.180 | 35.3 | 0.174 | 35.7 | 0.217 | 35.8 | 0.728 | 6.93 | <0.001 |

| Pack years smoking | 31.5 | 0.960 | 25.2 | 0.947 | 19.9 | 1.169 | 14.1 | 4.019 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| PA/day (h)a | 3.0 | 0.960 | 3.2 | 0.094 | 3.3 | 0.116 | 4.0 | 0.399 | 2.8 | 0.038 |

| Age of mother | 69.0 | 0.620 | 70.1 | 0.595 | 74.6 | 0.748 | 76.5 | 2.529 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Age of father | 69.2 | 0.508 | 69.6 | 0.491 | 70.7 | 0.606 | 69.6 | 2.069 | 1.15 | 0.328 |

aAdjusted for age at baseline

bAdjusted for age and height at baseline

cAdjusted for age, weight, and height at baseline

Table 2.

Health condition at the baseline when participants were on average 62 years old according to survival category

| Longevity | χ 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −79 years (n = 801) | 80–89 years (n = 846) | 90–99 years (n = 545) | 100+ years (n = 47) | ||

| % | % | % | % | p | |

| Diabetes | 16 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0.001 |

| High blood pressure | 31 | 23 | 19 | 9 | <0.001 |

| Heart attack | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Angina pectoris | |||||

| Other heart disease | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0.073 |

| Gout | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0.003 |

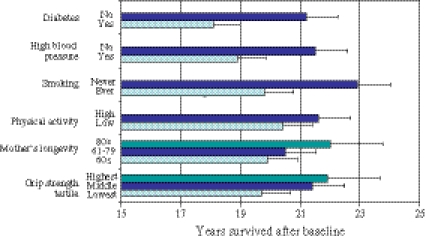

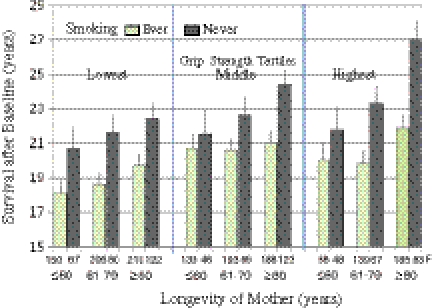

The adjusted length of life was 2.2 years longer among those in the highest tertile of grip strength distribution compared with the lowest third (Fig. 1). If the mother had survived to ≥80 years, the survival of offspring was 2.1 years longer compared with if the mother died at age ≤60 years. For never vs. ever smoking, the difference was 3.1 years. Figure 2 shows the average survival times in groups according to mother’s longevity, grip strength, and smoking status. For example, if the participants were in the highest grip strength tertile, their mother had survived ≥80 years, and they had never smoked, the average remaining survival time after baseline was 27.0 years (SE = 1.06). In contrast, for those in the lowest grip strength tertile, whose mothers died at age ≤60 years, and who had smoked, the survival time was 18.1 years (SE = 0.768). We examined all possible predictor interactions on survival, but none were statistically significant, suggesting that their influences may be additive (data not shown). The interactions of baseline age and baseline predictors on length of life were statistically not significant (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted mean lengths of survival (+SE) according to baseline predictors among 2,240 men with mortality followed up for 44 years. All differences are statistically significant with p ≤ 0.012. All values are adjusted for age at baseline

Fig. 2.

Adjusted mean lengths of survival (+SE) among never vs. ever smoking men according to grip strength at the age of 56–68 years and mothers’ longevity. The effects of smoking, grip strength, and mothers’ age were statistically significant (p < 0.001)

The centenarians had 2.5 times the odds of having belonged in the highest third of grip strength compared with those who died at the age of ≤79 years. The odds for never smoking were almost six times higher, respectively. Centenarians more than twice as often had a mother who survived 80 years or more than those who died at 79 years or younger (Table 3). Similar gradient associations but lower odds were observed for nonagenarians and octogenarian when compared with those who died at the age of 79 years or earlier. When we adjusted the grip strength model for each variable in Table 3 one at a time, we observed that adding smoking in the model increased the OR for becoming centenarian in the highest (OR = 3.03 95% CI = 1.42–6.42) and middle (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.10–7.21) grip strength tertiles due to the higher proportion of smokers in them. Adding mother’s age in the model decreased the grip strength OR’s to 2.43 (95% CI = 1.16–5.08) and 1.98 (95% CI = 0.81–4.85), respectively, suggesting that both of these variables operated through the same or overlapping pathways to longevity. Adjustment for other variables or including all variables in the model did not cause marked changes. Similarly, only minor changes in the OR’s of the grip strength tertiles in nonagenarian and octogenarian models were observed after corresponding adjustments in the models.

Table 3.

Bivariate effects of baseline predictors on the odds for surviving to become centenarian vs. dying at the age of 79 years or earlier

| 100+ vs. ≤79 years | 90–99 vs. ≤79 years | 80–89 vs. ≤79 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Grip strength tertilesa | ||||||

| Highest vs. lowest | 2.52 | 1.23–5.10 | 1.60 | 1.17–2.18 | 1.36 | 1.04–1.80 |

| Middle vs. lowest | 2.02 | 0.84–4.87 | 1.44 | 1.10–1.89 | 1.47 | 1.16–1.88 |

| Never vs. ever smokingc | 5.75 | 3.06–10.80 | 2.13 | 1.68–2.71 | 1.36 | 1.09–1.69 |

| Physical activity ((h)day) | 1.13 | 1.02–1.25 | 1.04 | 1.00–1.09 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.06 |

| No diabetesd | 2.84 | 0.87–9.30 | 2.07 | 1.45–2.96 | 1.63 | 1.22–2.19 |

| Normal blood pressured | 4.87 | 1.73–13.72 | 1.90 | 1.46–2.47 | 1.50 | 1.21–1.87 |

| Mother’s age | ||||||

| ≥80 vs. ≤60 years | 2.26 | 1.04–4.90 | 1.84 | 1.37–2.47 | 1.18 | 0.92–1.52 |

| 61–79 vs. ≤60 years | 0.82 | 0.33–2.05 | 1.30 | 0.96–1.76 | 1.01 | 0.78–1.31 |

Similar comparisons shown for nonagenarians and octogenarians. Logistic regression models

aAdjusted for age, height, and weight at Exam 1; cutoffs for tertiles 33 and 38 kg

bAdjusted for age, height and smoking (never/ever) at Exam 1

cAdjusted for age and height at Exam 1

dAdjusted for age at baseline

Discussion

The increasing longevity of populations will have enormous political and economic consequences (Olshansky et al. 2009). Centenarians may have delayed onset of disease and disability (Engberg et al. 2009; Willcox et al. 2007). Consequently, research on exceptional longevity will help us understand healthy aging and eventually to design interventions to minimize disease, disability, and premature mortality. The main results of our study following a cohort of men for 44 years until their death were that having good muscle strength, being physically active, not smoking, and absence of chronic conditions at the age of 62 years, as well as having a long-lived mother each contributed 1 to 3 years for the length of remaining life. The same variables also correlated with the likelihood of becoming a centenarian. These findings expand the earlier analyses showing that low midlife grip strength predicts an increased risk of disability and death (Rantanen et al. 1999, 2000; Cooper et al. 2010). Multivariate analyses suggested that mother’s longevity and son’s grip strength and longevity may be explained partly by the same genetic or environmental factors. This has not been reported before. An earlier study among people around the age of 70 observed that for every additional 10 years their parents had lived, their grip strength increased by 0.32 kg (95% CI = 0.00–0.63), and the risk of having, e.g., diabetes or hypertension decreased by approximately 20% (Frederiksen et al. 2002).

Contrary to earlier reports, paternal longevity did not correlate with son’s longevity in our data (Kemkes-Grottenthaler 2004). It is possible that during the lifetime of the fathers of our participants, certain influences related to premature mortality may have been experienced more often in males than in females. Alternatively, greater maternal longevity may be adaptive for the enhancement of offspring survival and reproduction. Interestingly, mitochondrial genes have been found to be potential contributors to human longevity and are heritable solely through maternal lines (De Benedictis et al. 1999).

Regardless of physiological reserve marked by grip strength or inheritance marked by maternal longevity, longevity was increased with physical activity and reduced with smoking—and, importantly, these influences were additive. Longevity appears in this cohort to be a result of accumulation of good inheritance, health, physiological reserve, and lifestyle choices. Our findings validate conclusions based on earlier cross-sectional or retrospective studies among centenarians (Engberg et al. 2009; Christensen et al. 2009; Hagberg and Samuelsson 2008).

The current cohort comprises a high proportion of exceptionally long-lived individuals. The majority of the overall birth cohort 1900–1909 had died before 1965 when the study started as for that cohort, the average life expectancy in the USA was 47.6–52.5 years (Arias 2004). Nevertheless, in the current cohort, becoming a centenarian was much rarer than anticipated in future cohorts. Some project that most babies born since 2000 in countries with long life expectancies will celebrate their 100th birthdays (Christensen et al. 2009).

Contrary to earlier studies, indicators of socioeconomic disparities did not correlate with longevity in the current study. Possibly, in our cohort, the living conditions and health care availability did not differ extensively according to social position. At the beginning of the study, the participants had already exceeded the average life span of their birth cohort and may represent a selected group of survivors where social position no longer correlated with survival.

There are several strengths to this study: the prospective design and over four decades of follow-up, essentially complete data on life span for a large number of men, and no study attrition. Importantly, handgrip strength an objective, validated measure of physiologic reserve and a potential biomarker of aging, and other pertinent data, were collected in a standardized manner at the baseline when participants were of average 62 years of age. Within a birth cohort, we compared the long-lived groups of interest with a shorter life span reference group, and therefore our study is not confounded by cohort effects. Finally, we were able to study actual years lived rather than estimate expected survival times.

The limitations of the study are that it comprised only men, only one ethnic group, and the parental longevity was reported by the participants and was incomplete for approximately 10%. On the other hand, utilizing a monoethnic group avoids problems inherent in many studies of human longevity, such as population stratification artifact. The cohort had, as a group, exceeded the average male life span of their US birth cohort when entering the study. The selective mortality which took place before this study started may have caused an underestimation rather than overestimation of the associations studied. The baseline of the current study was collected in the 1960s, which explains why data on several promising predictors of health and longevity under intensive research today were not collected. The prevalence of some mortality risk factors at the baseline of this study during the 1960s was at a different level than today, which may have resulted in the underestimation of the importance of some risk factors prevalent today. For example, the prevalence of obesity (body mass index of 30 or more) was much lower among our baseline participants (1%) than currently among white middle-aged men in the USA (34%; Flegal et al. 2010). Unfortunately, we were unable to study healthy aging phenotypes as outcomes. However, some studies show that among people surviving to very old age, disease onset is delayed (Engberg et al. 2009). Consequently, the current analyses on length of life most likely provide us with information about healthy aging as well.

The current findings suggest that having good grip strength and a long-lived mother may indicate physiological reserve and inherited resilience to aging processes, which may be enhanced with physical activity and diminished with smoking. The probability to survive to extreme old age is a sum of both constitutional and behavioral factors. People with less physiological resilience to aging process may enhance their longevity by healthy lifestyle choices. Our study provides unique information useful to scientist studying genetics of aging processes (Karasik 2011), while we at the same time have a public health message for individuals and practitioners who wish to promote healthy aging.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to the participants in the Honolulu–Asia Aging Study for their outstanding commitment and cooperation and to the entire Honolulu–Asia Aging Study staff for their expert and unfailing assistance. This work was financially supported by Academy of Finland and grants 5U01 AG19349, and 5UO1 AG017155, R01 AG027060-01) and contract N01-AG-4-2149 from the NIA, National Institutes of Health, and by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Arias E (2004) United States Life Tables, 2001. National Vital Statistic Reports 52(14), pp 1–39 [PubMed]

- Autenrieth C, Schneider A, Döring A, et al. Association between different domains of physical activity and markers of inflammation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(9):1706–1713. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a15512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson S, Andersson T, Lichenstein P, Michalesson K, Ahlblom A. Physical activity and mortality: is the association explained by genetic selection? Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(3):255–259. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R, Group MR, FALCon and HALCyon Study Teams Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curb JD, Marcus EB, Reed DM, MacLean C, Yano K. Smoking, pulmonary function, and mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 1990;1(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(90)90016-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis G, Rose G, Carrieri G, et al. Mitochondrial DNA inherited variants are associated with successful aging and longevity in humans. FASEB J. 1999;13(12):1532–1536. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.12.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg H, Oksuzyan A, Jeune B, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Centenarians—a useful model for healthy aging? A 29-year follow-up of hospitalizations among 40000 Danes born in 1905. Aging Cell. 2009;8(3):270–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Izmirlian G, Leveille S, et al. Smoking, physical activity, and active life expectancy. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(7):645–653. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Loucks EB, Berkman LF. Social integration and concentrations of C-reactive protein among US adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen H, McGue M, Jeune B, Gaist D, Nybo H, Skytthe A, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Do children of long-lived parents age more successfully? Epidemiology. 2002;13(3):334–339. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg B, Samuelsson G. Survival after 100 years of age: a multivariate model of exceptional survival in Swedish centenarians. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(11):1219–1226. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.11.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim AA, Petrovitch H, Burchfield CM, et al. Effects of walking on mortality among nonsmoking retired men. N Engl J Med. 1988;338(2):93–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801083380204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskind AM, McGue M, Holm NV, Sørensen TI, Harvald B, Vaupel JW. The heritability of human longevity: a population-based study of 2872 Danish twin pairs born 1870–1900. Hum Genet. 1996;97(3):319–323. doi: 10.1007/BF02185763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M, Paavilainen P, Lehtimäki T, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein as predictors of mortality in nonagenarians: the Vitality 90+ Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(9):1016–1021. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, et al. C-reactive protein concentrations and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participants meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9709):132–140. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasik D. How pleiotropic genetics of the musculoskeletal system can inform genomics and phenomics of aging. AGE. 2011;33(1):49–62. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9159-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemkes-Grottenthaler A. Parental effects on offspring longevity—evidence from 17th to 19th century reproductive histories. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31(2):139–158. doi: 10.1080/03014460410001663407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. The genetics of aging. Nature. 2010;464(7288):504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucks EB, Berkman LF, Gruenewald TL, Seeman TE. Relation of social integration to inflammatory marker concentrations in men and women 70 to 79 years. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(7):1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell BD, Hsueh WC, King TM, Pollin TI, Sorkin J, Agarwala R, Schäffer AA, Shuldiner AR. Heritability of life span in the Old Order Amish. Am J Med Genet. 2001;102(4):346–352. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas BJ, Hsu FC, Brinkley TJ, Chirch T, Goodpaster BH, Kritchebsky SB, Pahor M. Exercise training and plasma C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2045–2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky SJ, Goldman DP, Zheng Y, Rowe JW. Aging in America in the twenty-first century: demographic forecasts from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on an Aging Society. Milbank Q. 2009;87(4):842–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Masaki K, Foley D, Izmirlian G, White L, Guralnik JM. Grip strength changes over 27 years in Japanese-American men. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85(6):2047–2053. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, et al. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA. 1999;281(6):558–560. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Harris T, Leveille S, et al. Muscle strength and body-mass index as long-term predictors of mortality in Japanese-American men. J Gerontol: Med Sci. 2000;55(3):M168–M173. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.3.M168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Volpato S, Ferrucci L, Heikkinen E, Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Hand grip strength, cause-specific and total mortality in older disabled women: exploring the mechanism. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):636–641. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask K, O’Malley E, Druss B. Impact of socioeconomic, behavioral and clinical risk factors on mortality. J Public Health. 2009;31(2):231–238. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed T, Fabsitz RR, Selby JV, Carmelli D. Genetic influences and grip strength norms in the NHLBI twin study males aged 59–69. Ann Hum Biol. 1991;18(5):425–432. doi: 10.1080/03014469100001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senchina DS, Kohut ML. Imunological outcomes of exercise in older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(1):3–16. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2007.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silventoinen K, Magnusson PK, Tynelius P, Kaprio J, Rasmussen F. Heritability of body size and muscle strength in young adulthood: a study of one million Swedish men. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(4):341–349. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen K, Sipilä S, Alen M, et al. Heritability of maximal isometric muscle strength in older female twins. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96(1):173–180. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00200.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, Suzuki M. Exceptional human longevity. In: Karasek M, editor. Aging and age-related diseases: the basics. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 459–509. [Google Scholar]

- Willcox BJ, He Q, Chen R, et al. Midlife risk factors and healthy survival in men. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2343–2350. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, Shimajiri S, Kurechi S, Suzuki M. Aging gracefully: a retrospective analysis of functional status in Okinawan centenarians. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2007;15(3):252–256. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31803190cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashin AI, De Benedictis JW, Vaupel Q, et al. Genes and longevity: lessons from studies of centenarians. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(7):B319–B328. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.B319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]