Abstract

Background

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) patients are at high risk for acute respiratory illness (ARI).

Objective

Evaluate safety/efficacy of a proprietary extract of Panax quinequefolius, CVT-E002 (Afexa Life Sciences) to reduce ARI.

Methods

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial:293 subjects with early-stage, untreated CLL January-March, 2009.

Results

ARI days were common occurring on about 10% of days during the study period. There were no significant differences of the two a priori primary endpoints: ARI days (8.5 ± 17.2 for CVT-E002 vs. 6.8 ± 13.3 for placebo) or severe ARI days (2.9 ± 9.5 for CVT-E002 vs. 2.6 ± 9.8 for placebo). However, 51% percent of CVT-E002 vs. 56% of placebo recipients experienced at least one ARI (diff -5%, 95% C.I. -16%,7%); more intense ARI occurred in 32% of CVT-E002 vs. 39% of placebo recipients (diff -7%, 95% C.I. -18%, 4%), and symptom-specific evaluation showed reduced moderate-severe sore throat (p = 0.004) and a lower rate of grade ≥3 toxicities (p = 0.02) in CVT-E002 recipients. Greater seroconversion (4-fold increases in antibody titer) vs. 9 common viral pathogens was documented in CVT-E002 recipients (16% vs. 7%; p = 0.04).

Limitations

Serologic evaluation of antibody titers were not tied to a specific illness, but evaluated over the entire study period.

Conclusion

CVT-E002 was well tolerated.CVT-E002 did not reduce the number of ARI days or antibiotic use; however, there was a trend toward reduced rates of moderate-severe ARI and significantly less sore throat, suggesting the increased rate of seroconversion most likely reflects CVT-E002-enhanced antibody responses.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, respiratory infection, ginseng

1. Introduction

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is the most common adult leukemia accounting for nearly one-third of all leukemias [1,2]. Almost all cases of CLL occur in adults 50 and over with a median age at diagnosis in the mid-60's [2,3]. Median survival is 4-5 years after initiation of treatment, but early-stage patients often do not require treatment for many years after diagnosis [1]. Both the underlying CLL and its treatment result in immune compromise, particularly poor antibody responses, and infection is common [1,4]. The most common infections in CLL patients are acute respiratory infections (ARIs) [4]. Many of these ARIs are viral, but antibiotics are frequently prescribed since it is difficult to differentiate viral from bacterial infection. The rate of major infection, i.e. infection severe enough to require hospitalization or treatment with parenteral antibiotics, is 0.04, 0.06, and 0.14 per patient per month in patients being treated with chlorambucil, fludarabine or the combination, respectively [3]. Untreated CLL patients are more prone to infection than similar age patients with non-malignant co-morbidity (ie. myocardial infarction) based on data published over 30 years ago [5], but there are no more recent data, and those data included patients with a mix of CLL stages. Since the vast majority of CLL patients are over age 60, it is likely that immune senescence, the waning of immunity with advanced age, is also a risk factor for infection [6]. Recent studies [7] suggest the mean number of ARI days during the respiratory illness winter season within this age group is about 8 [7].

Strategies to prevent infection are problematic in CLL. Inadequate antibody responses render vaccines less effective [1-4]. Infusion of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been used in subjects with low serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) (< 500 mg/dl). However, IVIG use is controversial due to supply issues, lack of consensus on frequency of administration or dose, and questionable cost-effectiveness of this very expensive therapy (approximately $11,000,000/quality-adjusted life year gained) [2]. Prophylactic antibiotics are much less expensive, but this strategy likely enhances antimicrobial resistance, has poor compliance, and prophylaxis for common viral pathogens is not available [1-4]. Thus there is a pressing need for effective, low-cost interventions that enhance immunity, reduce infection risk and limit antibiotic use in CLL patients.

CVT-E002™, a patented mixture of polysaccharides isolated from Panax quinquefolius (Afexa Life Sciences, Edmonton, Canada) has been investigated as an immunomodulatory compound. The accumulated data on the mechanism of action indicates that CVT-E002 is an innate immune modulator, acting through toll-like receptors on the surfaces of these cells. This activation leads to increased numbers and function of cells within both the innate and adaptive immune systems [8-11]. CVT-E002 reduces the incidence of ARIs in adults [7,12-14]. Importantly, three of these studies [7,12,14] were performed in older adults, the population most affected by CLL. One study in healthy, community-dwelling seniors showed CVT-E002 reduced the number of days with respiratory illness symptoms by over 50% [12]. Another study was conducted in long-term care (nursing home) residents [7] with the main endpoint being laboratory-confirmed symptomatic influenza; 7/101 placebo recipients had confirmed influenza or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) illness vs. only 1/97 CVT-E002 recipients (p = 0.033). In the third study, conducted in 783 community-dwelling seniors [14], incidence of respiratory illness was decreased by one-third in the CVT-E002 recipients (p = 0.04).

In addition to older age, there are important parallels of subjects in published CVT-E002 studies [7,12,14] with CLL patients. Subjects in two studies [7,14] were highly immunized (> 90% received an influenza vaccine within two years); thus, most cases of influenza represented vaccine failure. Also, the characteristics of long-term care residents: older age, multiple co-morbidities, and impaired immunity including ineffective vaccine responses, closely resemble the population and immune milieu of CLL patients. Based on these parallels and the need for effective preventive measures for ARI in CLL patients, we performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of CVT-E002 to reduce ARI and the need for antibiotic treatment in CLL patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subject selection and enrollment

Subjects were enrolled between November 1 and December 31, 2008 at sites affiliated with the Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) Research Base of Wake Forest University's Comprehensive Cancer Center or the NCI's Cancer Trials Study Unit (CTSU). Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 18, phenotypic evidence of CLL (flow cytometry or bone marrow), ECOG (Zubrod) performance status ≤ 2, life expectancy > 12 months, and able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: HIV, cirrhosis, or autoimmune disease (e.g. multiple sclerosis), malignancy other than CLL (non-melanoma skin cancers & carcinoma in situ of the cervix were allowed), creatinine clearance ≤ 50 ml/min, SGOT (AST) or SGPT (ALT) ≤ 2.5 ULN, Total Bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × ULN, current or prior treatment with fludarabine, alemtuzumab, rituximab, IVIG, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, current or recent (w/in 3 months) therapy with chlorambucil, current treatment with corticosteroids ≥ equivalent 20 mg/day prednisone, use of antibiotic prophylaxis other than trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), current use of warfarin, allergy to ginseng products, or current use of other herbal products (and unwilling to discontinue).

Subjects were stratified by: use of prophylactic TMP-SMX (yes/no), serum IgG (≤ 500 mg/dL vs. > 500 mg/dL), and influenza vaccine status for the enrollment year (yes/no), and randomized (1:1) to receive CVT-E002 (200 mg twice daily) or matching placebo (microcrystalline cellulose) orally. Treatment continued from the time of enrollment through April 30, 2009 to allow for a consistent period of time during which all subjects were on protocol (January 1-April 30). This period encompassed the time of maximum respiratory tract infection and influenza risk (January-April) regardless of geography in the U.S.

2.2 Definitions and Main Outcomes

The main outcome measured was ARI days during a fixed three-month period (January 1-March 31). Subjects took CVT-E002/placebo for an additional month to ensure secondary endpoints were met and to encompass a potential late influenza season in the treatment period. All subjects were seen at enrollment, week 4, week 10 and end-of-study, and a follow-up phone call was performed 4 weeks later to assess any adverse events.

Subjects kept a daily symptom diary to determine the number of ARI days, and study personnel instructed subjects at enrollment regarding each item in the diary. Symptoms specifically queried daily included: cough, sore throat, nasal/sinus congestion, runny nose, feverishness, chills/sweats, myalgias (muscle aches), fatigue, headache, poor endurance or increased shortness of breath. Each symptom was rated on a 0-3 scale of severity (0=absent; 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe). If they felt feverish, subjects were asked to take their temperature orally with a home thermometer. Subjects also indicated whether symptoms limited participation in usual activities.

An “ARI day” was defined as any day on which the subject experienced ≥ 1 respiratory symptoms (cough, sore throat, nasal or sinus congestion, or runny nose) and ≥ 1 systemic symptom (feverishness, chills/sweats, myalgias, fatigue, headache, poor endurance or increased shortness of breath). Use of the rating scale for each symptom allowed the first validation of the instrument in CLL patients with other commonly used URI scales such as the modified Jackson criteria for “colds” [15] as later refined by Gwaltney [16]. Severe ARI days were defined as an ARI day + one of the following: fever (oral temperature > 100°F) or limited participation in usual activities.

Antibiotic use days (AUDs) were defined as days on which systemic (oral/parenteral) antibiotics were given once or multiple times for any reason, excluding prophylactic TMP-SMX. Subjects recorded the information on antibiotic use forms and entries were confirmed by study personnel during visits.

Toxicities were evaluated by the standard Common Toxicity Criteria – NCI Version 3.0. Any untoward adverse events were reported to the IRB and the CCCWFU Clinical Research Oversight Committee for further review.

2.3 Serologic responses to common respiratory viruses

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) was performed to detect virus-specific serum IgG for nine respiratory viruses: influenza A & B, RSV, parainfluenza (PIV) virus serotypes 1-3, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), and coronavirus 229E and OC43 per published methods [17-20]. Briefly, antigens were produced from virally infected whole cell lysates for all viruses except RSV. Purified viral surface glycoproteins were used as antigen for RSV EIA according to published methods [17]. Paired serum samples were screened at a single dilution and those showing a ≥ 1.5 increase in optical density reading from baseline to end-of-study specimens were further tested by full dilution to determine antibody titer. Serial two-fold dilutions of each sample were tested in duplicate. Seroconversion was defined as a ≥ 4-fold rise in antibody from baseline to end-of-study.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to assess baseline group differences in categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Fisher exact tests and Poisson regression were used to compare toxicities in the two groups. Efficacy outcomes were assessed over the three-month period between January and March (primary analyses) and toxicity outcomes over the entire study. Negative binomial regression was used to assess the effect of treatment arm on the rate of events. Exposure times were included in the models as not all subjects returned all diaries. The negative binomial model was used as the variances of the outcomes were greater than what was predicted by a Poisson model. In these models, age, gender, and strata were used as covariates. A Fisher s exact test was used to assess differences in the proportion of subjects with seroconversion vs. measured viral pathogens and Poisson regression was used to compare seroconversion rates.

Originally designed for a sample size of 112 patients per group, which would allow detection of a 30% difference in the number of ARI days with 90% power at the 5% two-sided level of significance, assuming a coefficient of variation of 80%, accrual was bolstered to account for an assumed 20% drop-out rate.

3. Results

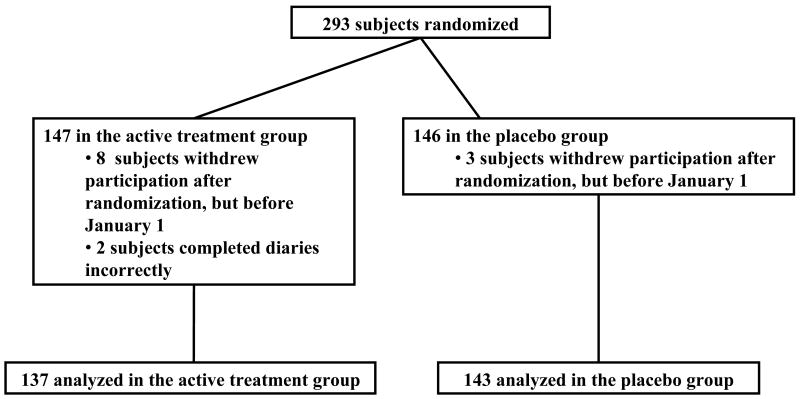

Two hundred ninety-three subjects were enrolled from November 1, 2008-December 31, 2008; 147 subjects were randomized to active drug and 146 to placebo (Figure 1). Twelve patients did not complete any diaries; 11 who decided not to participate in the study after being randomized, and one who refused to complete the diaries. One additional patient completed the diaries incorrectly. These 13 subjects were excluded, leaving 280 analyzed subjects, 137 in the active treatment group and 143 in the placebo arm. Table 1 shows subject characteristics in each group; there were no significant differences between groups in any of the characteristics. One hundred twenty subjects in the active treatment group and 125 subjects in the placebo arm completed the study. Reasons for withdrawal were similar between groups – only two subjects in the active group and one subject in the placebo group withdrew due to toxicity. In both groups, 92% of all daily diaries were completed and returned. Mean adherence with prescribed medication (by patient self-report on completed diaries) was 97% in both groups.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of subjects enrolled in the study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of evaluable subjects.

| Characteristic | CVT-E002 | Placebo | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| # (%) | # (%) | ||

| Total | 137 (100) | 143 (100) | |

| Age | .810 | ||

| Median (range) | 65 (43-87) | 66 (44-82) | |

| <50 | 6 (4) | 9 (6) | |

| (50-59) | 37 (27) | 30 (21) | |

| (60-69) | 46 (34) | 56 (39) | |

| (70-79) | 36 (26) | 44 (31) | |

| 80+ | 12 (9) | 4 (3) | |

| BMI | .927 | ||

| Median (range) | 27.9 (17-47) | 28.2 (18-41) | |

| Underweight-Normal (< 25) | 30 (22) | 34 (24) | |

| Overweight (25 – 30) | 57 (42) | 61 (43) | |

| Obese (>30) | 50 (36) | 48 (34) | |

| Strata | --- | ||

| 3 – TMP/SMX - Yes, IgG > 500, Influenza vaccine - Yes | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| 4 – TMP/SMX - Yes, IgG > 500, Influenza vaccine - No | |||

| 5 – TMP/SMX - No, IgG <= 500, Influenza vaccine - Yes | |||

| 6 – TMP/SMX - No, IgG <= 500, Influenza vaccine - No | |||

| 7 – TMP/SMX - No, IgG > 500, Influenza vaccine - Yes | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| 8 – TMP/SMX - No, IgG > 500, Influenza vaccine - No | 94 (69) | 99 (69) | |

| Race | .623 | ||

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Black | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| White | 136 (99) | 138 (97) | |

| Sex | .760 | ||

| Female | 59 (43) | 59 (41) | |

| Male | 78 (57) | 84 (59) | |

| ECOG Performance Status | .583 | ||

| 0 | 125 (91) | 133 (93) | |

| 1 | 12 (9) | 10 (7) | |

3.1 ARI Days and Antibiotic Use

An ARI occurred in 54% of subjects overall during the three-month primary study period of interest. The overall rate of ARIs was 0.09 per patient day; or, on average, subjects experienced an ARI approximately 1 of every 11 days. There were no significant differences in the two a priori primary endpoints: 1) ARI days were 8.5 ± 17.2 in the CVT-E002 recipients vs. 6.8 ± 13.3 in the placebo group (Rates: 10.5% ± 20.1% vs. 8.2% ± 15.6%, respectively, p = .23); 2) Severe ARI days 2.9 ± 9.5 in CVT-E002 recipients vs. 2.6 ± 9.8 in placebo recipients (Rates: 3.4% ± 11% vs. 3.1% ± 12%, respectively, p = .78), or the two a priori secondary endpoints: 1) Antibiotic use days were 1.8 ± 5.0 for CVT-E002 vs. 2.3 ± 7.1 for placebo, p = .37; 2) Jackson-defined cold days 2.1 ± 6.6 for CVT-E002 vs. 1.2 ± 3.2 for placebo, p = .23.

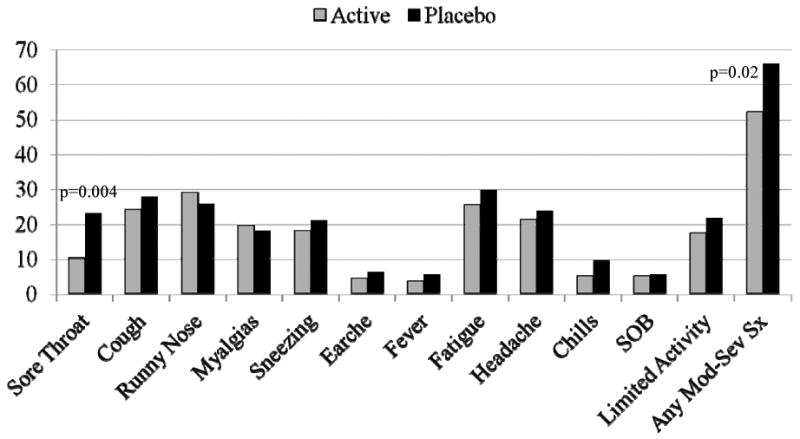

3.2 Incidence of ARI

When data were examined as the proportion of subjects experiencing an ARI, 51% of CVT-E002 recipients experienced at least one ARI day vs. 56% of placebo recipients (difference -5%, 95% C.I. -16%,7%, p = .42), and 27% of CVT-E002 recipients experienced at least one severe ARI day vs. 30% of placebo recipients (difference -3%, 95% C.I. -13%,8%, p = .57). More intense ARIs, defined as the occurrence of multiple mild symptoms or one or more moderate to severe symptoms, were experienced by 32% of CVT-E002 recipients vs. 39% in the placebo group (difference -7%, 95% C.I. -18%,4%, p = .22). Analysis of specific moderate-severe symptoms (sore throat, cough, runny nose, congestion, sneezing, earaches, myalgias, fever, fatigue, headache, chills and shortness of breath) showed a significantly lower rate of sore throat (p = 0.004) and any moderate-severe symptom (p = 0.02) in the CVT-E002 group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Respiratory illness symptoms reported as moderate-severe. The percent of subjects in each group reporting moderate-severe acute respiratory illness symptoms (worst reported severity Jan-Mar) is shown.

3.3 Seroconversion vs. common respiratory viruses

Of 191 subjects with serum specimens available at baseline and end-of-study, 22 experienced seroconversion to a common respiratory virus (Table 2); 15/91 CVT-E002 recipients vs. 7/100 in the placebo group (Table 2; p = 0.04). As seroconversion to > 1 virus could occur, we also determined that 27 seroconversions occurred in the 22 subjects for a seroconversion rate/cold season of 0.22 in CVT-E002 vs. 0.07 in placebo recipients (p = 0.005).

Table 2.

Number of subjects experiencing a seroconversion (≥ 4-fold rise in antibody titer) vs. nine common respiratory viruses during the entire study period; 191 subjects had serum samples available both at baseline and end-of-study and were thus included in the analysis. Totals are given both as proportion of subjects in each group experiencing seroconversion/cold season and, since individuals could seroconvert to > one virus, the rate of seroconversions/cold season by group is also shown.

| Virus | CVT-E002 (n=91) | Placebo (n=100) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| influenza A | 1 | 0 | 0.48 |

| influenza B | 1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| respiratory syncytial virus | 1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| human metapneumovirus | 6 | 1 | 0.06 |

| parainfluenza type 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| parainfluenza type 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.48 |

| parainfluenza type 3 | 1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| coronavirus 229E | 3 | 1 | 0.35 |

| coronavirus OC43 | 5 | 1 | 0.10 |

| Proportion of subjects with seroconversion/cold season | (1591) 16% | (7/100) 7% | 0.04 |

| Seroconversion rate/cold season | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.005 |

The study design did not allow for serologic sampling before/after each ARI episode so one cannot match a given ARI event with a specific viral etiology. However, of the 22 subjects experiencing seroconversion, 5 were asymptomatic throughout the study period – i.e. experienced no ARI days; four in the CVT-E002 group, and one in the placebo group, suggesting asymptomatic conversion. The five subjects had seroconversion vs. coronavirus 229E or PIV type 2 suggesting all influenza, RSV, hMPV, and PIV types 1 and 3 were likely symptomatic.

3.4 Immune and disease activity parameters

There were no significant differences in either group in pre- vs. post-WBC, platelet count, total serum IgG level, percent CD4 T cells, or beta-2 microglobulin. Given the short duration of the study one would not expect progression of CLL in many patients and there was no difference between groups pre- por post-intervention as measured by Rai Stage.

3.5 Safety

CVT-E002 was well tolerated. Toxicities were evaluated both as the number of patients experiencing toxicity and the rate over time as a subject could experience > 1 event; the overall number of subjects and rate of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs was not different between groups. The most commonly reported AEs in both groups (number of subjects in the active group vs. the placebo group) were: joint pain (47 vs. 58), insomnia (45 vs. 31), hyperglycemia (30 vs. 39), and headache (31 vs. 37). There was, however, a difference in the rate of severe (grade 3 or higher) toxicities reported between groups. From January 1-April 30, 13/142 subjects on the control arm compared to 8/135 on the CVT-E002 arm experienced at least one grade 3 or higher toxicity (p = .37). However, control patients experienced a greater cumulative number of grade 3+ toxicities (25 vs. 12, p = .02).

4. Discussion

Acute Respiratory Illness (ARI) is common in CLL. ARI symptoms occurred on 9% of all days from January 1 to March 31in enrolled subjects. CVT-E002 did not significantly reduce ARI days or antibiotic use though a trend was noted for CVT-E002-associated reductions in the rate of moderately-severe ARI and significant reductions were seen in the rate of either any mod-severe symptom, or mod-severe sore throat. A greater proportion of CVT-E002 recipients experienced seroconversion to common viruses (16% vs. 7%; p = 0.04).

Previous studies have noted high rates of respiratory infection in CLL patients (1-5), but nearly all prior studies examined patients with CLL in later stages that require treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the incidence of ARI in untreated, early-stage CLL patients. More than 50% of subjects in this study experienced at least one ARI. Further, ARI symptoms were reported on ∼9% of the 90 days from January 1st to March 31st, a rate similar to previously published data in healthy community-dwelling older adults [12]. The vast majority of days symptoms were mild and did not result in antibiotic use. The average number of antibiotic use days was ∼ 2 in both groups. The mild nature of ARI symptoms may have been due to relatively mild influenza activity during 2008-2009 (http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluactivity.htm); indeed, of 191 subjects with serologic data, only 3 episodes of influenza seroconversion were confirmed (Table 2). A limitation of this study is that symptoms and serology were used to identify ARIs – prospective surveillance using PCR or viral culture would have been preferable, but was beyond the scope of support available for this study.

In four prior randomized controlled studies in adult populations, CVT-E002 was safe and reduced ARI risk [7, 12-14]. This is the first study in CLL subjects; the safety and tolerability of CVT-E002 was again evident in this trial with no difference vs. placebo recipients. However, there was no effect on ARI illness days or antibiotic use, the a priori-defined endpoints. The lack of efficacy for reaching ARI endpoints in CLL patients could be due to multiple factors. The accumulated data on the mechanism of CVT-E002 indicates that CVT-E002 is an innate immune modulator, acting through toll-like receptors on the surfaces of these cells. This activation leads to increased numbers and function of cells within both the innate and adaptive immune systems [8-11]. However, there is no current method to measure blood/tissue levels of the “active compound” nor a measurable bioassay to allow a correlation of outcome with evidence of drug effect. It is possible that these pathways are not sufficiently influenced by CVT-E002 at the dose utilized to demonstrate clinical benefit in CLL patients, or that the toll-like receptor pathway is impaired in CLL patients. However, the results regarding seroconversion suggest otherwise (see below) and indicate that further study of higher doses of CVT-E002 is warranted. In addition, it is worth noting that the variability in the symptom-defined measures was far greater than that seen in previous studies in non-leukemic participants, which may have contributed to the failure to reach significance.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in CLL patients treated with an immune modulating agent to comprehensively evaluate seroconversion vs. multiple viral pathogens that cause ARI. The serologic data (Table 2) suggest 4-fold increases in antibody occurred more frequently in CVT-E002 recipients, reaching statistical significance for combined viral infection rates. Increased viral exposure risk in CVT-E002 recipients seems very unlikely. Further an increased risk for viral infection is not consistent with the clinical data that show a trend toward lower incidence of moderately-severe ARI in CVT-E002 recipients. The seroconversion data are much more consistent with enhanced immune responses as a result of CVT-E002 therapy. Sensitivity for detecting seroconversion rests on documenting a 4-fold rise in titer. CLL patients generally have impaired antibody responses [1,3-5]. Thus, a more likely explanation for the demonstrated seroconversion rate difference is a manifestation of CVT-E002 enhanced virus-specific antibody responses, a hypothesis being evaluated by our group and others.

5. Conclusions

In summary, ARI is a common complication in patients with untreated CLL with an average of one day in every ten being an ARI day during the winter respiratory virus season. CVT-E002 was well-tolerated, but did not reduce the number of ARI days, severe ARI days, the two a priori primary endpoint, or antibiotic use. CVT-E002 therapy, however, was associated with trends toward a reduced rate of more intense ARI and a significant reduction in the percent of subjects reporting moderately-severe sore throat, any moderate-severe symptom, or grade ≥3 toxicity. A significant increase in the rate of seroconversion vs. respiratory viral pathogens in CVT-E002 recipients most likely reflects augmented antibody responses. Future research should examine whether CVT-E002 can affect antibody titers after immunization in CLL patients, and whether higher doses of CVT-E002 might effectively reduce ARI incidence and severity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (grant 2U10CA81851-09-13) and Afexa Life Sciences, Inc. Presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2010 Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL.

Abbreviations list

- ARI

acute respiratory illness

- BMI

body mass index

- CCOP

Community Clinical Oncology Program

- CCCWFU

Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CTSU

Cancer Trials Study Unit

- CVT E002

proprietary polysaccharide extract of North American ginseng (Panax quinequefolius)

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- PIV

Parainfluenza virus

- RSV

Respiratory Syncitial virus

- TMP/SMX

trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Keating MJ, Kantarjian H. The Chronic Leukemias. In: Goldman, Ausiello, editors. Cecil Textbook of Medicine. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. pp. 1150–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens JM, Gramegna P, Laskin B, Botteman MF, Pashos CL. Chronic Lymphocytic Lekemia: Economic Burden and Quality of Life. Am J Ther. 2005;12:460–466. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000104489.93653.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison VA, Rai KR, Peterson BL, Kolitz JE, Elias L, Appelbaum FR, et al. Impact of Therapy with Chlorambucil, Fludarabine, or Fludarabine Plus Chlorambucil on Infections in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Intergroup Study Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9011. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3611–3621. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anaissie EJ, Kontoyiannis DP, O'Brien S, Kantarjian H, Robertson L, Lerner S, et al. Infections in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treated with Fludarabine. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:559–566. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twomey JJ. Infections Complicating Multiple Myeloma and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Arch Int Med. 1973;132:562–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.High KP. Infection as a Cause of Age-Related Morbidity and Mortality. Aging Res Rev. 2004;3:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McElhaney JE, Gravenstein S, Cole SK, Davidson E, O'Neill D, Petitjean S, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of a Proprietary Extract of North American Gensing (CVT-E200) to Prevent Acute Respiratory Illness in Institutionalized Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, Guilbert LJ, Ling L, Li J, Wu Y, Xu S, et al. Immunomodulating activity of CVT-E002, a proprietary extract from North American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001;53:1515–1523. doi: 10.1211/0022357011777882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, Guilbert LJ, Li J, Wu Y, Pang P, Basu TK, et al. A proprietary extract from North American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) enhances IL-2 and INF-γ productions in murine spleen cells induced by Con-A. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Predy GN, Goel V, Lovlin R, Basu TK. Immune modulating effects of daily supplementation of COLD-fX (a proprietary extract of North American ginseng) during influenza season in healthy adults. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2006;39:162–167. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal KL, Newton J, Patrick AJ. CVT-E002, a proprietary extract of North American ginseng, activates the vertebrate innate immune system to produce proinflammatory and anti-viral factors via MyD88 signaling. FASEB J. 2008;22:538. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McElhaney JE, Goel V, Toane B, Hooten J, Shan JJ. Efficacy of COLD-fX in the Prevention of Respiratory Symptoms in Community-Dwelling Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo Controlled Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:153–157. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Predy GN, Goel V, Lovlin R, Donner A, Stitt L, Basu TK. Efficacy of an extract of North American ginseng containing poly-furanosyl-pyranosyl-saccharides for preventing upper respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2005;173:1043–1048. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland S, Rittenbach K, Goel V, et al. Systematic Review of Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials of Daily Dosing of a North American Ginseng Extract (CVT-E002) J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:926. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson GG, Dowling HF, Spiesman IG, Boand AV. Transmission of the common cold to volunteers under controlled conditions. I. The common cold as a clinical entity. Arch Intern Med. 1958;101:267–78. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1958.00260140099015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwaltney JM, Jr, Hendley O, Patrie JT. Symptom severity patterns in experimental common colds and their usefulness in timing onset of illness in natural colds. Clin Inf Dis. 2003;36:714–23. doi: 10.1086/367844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falsey AR, Treanor JJ, Betts RF, Walsh EE. Viral respiratory infections in the institutionalized elderly: Clinical and epidemiologic findings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:115–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falsey AR, McCann RM, Hall WJ, Tanner MA, Criddle MM, Formica MA, et al. Acute respiratory tract infection in daycare centers for older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:30–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falsey AR, McCann RM, Hall WJ, Criddle MM, Formica MA, Wycoff D, et al. The “common cold” in frail older persons: Impact of rhinovirus and coronavirus in a senior daycare center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:706–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falsey AR, Erdman D, Anderson LJ, Walsh EE. Human metapneumovirus infections in young and elderly adults. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:785–790. doi: 10.1086/367901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]