Abstract

Background

Obesity-associated hyperlipidemia and hyperlipoproteinemia are risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Recently, ceramide-derived sphingolipids were identified as a novel independent CVD risk factor. We hypothesized that the beneficial effect of RYGB on CVD risk is related to ceramide-mediated improvement in lipoprotein profile.

Methods

A prospective study of patients undergoing RYGB was conducted. Patients clinical data and biochemical markers related to cardiovascular risk were documented. Plasma ceramide subspecies (C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, C18:1, C20:0, C24:0, and C24:1), ApoB100 and ApoA-1 were quantified preoperatively, 3 and 6 months post-RYGB, as was Framingham risk score. Brachial artery reactivity testing (BART) was performed before and 6 months after RYGB.

Results

Ten patients (9 female; age 48 yrs; BMI, 48.5±5.8 kg/m2) were included in the study. At 6 months post-op, mean BMI decreased to 35.7±5.0 corresponding to 51.3±10.0 % excess weight loss. Fasting total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, free fatty acids, ApoB100, ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio and insulin resistance estimated from HOMA-IR were significantly reduced compared to pre-surgery values. The ratio of ApoB100/ApoA-1 correlated with a reduction in ceramide subspecies (C18:0, C18:1, C20, C24:0 and C24:1) (p<0.05). ApoB100 and the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio also positively correlated with the reduction in TG, LDL and HOMA-IR (p<0.05). BART inversely correlated with ApoB100 and total ceramide (p=0.05). Furthermore, the change in BART correlated with the decrease in C16:0 (p<0.03).

Conclusion

Our data suggests that improvements in lipid profiles and CVD risk factors after gastric bypass surgery may be linked to changes in ceramide lipid. Mechanistic studies are needed to determine if this link is causative or purely correlative.

Keywords: RYGB, bariatric surgery, cardiovascular risk, ceramide, sphingolipids, apolipoproteins, ApoB100, Apo A-1, ApoB100/Apo A-1 ratio

Introduction

Numerous risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been identified, not least of which are obesity and its related comorbidities such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus 1. So strong are the associations between metabolic and cardiac diseases that the term ‘cardiometabolic syndrome’ became popular over the last decade, to describe the array of metabolic, hemodynamic and renal abnormalities which accompany visceral obesity and associated insulin resistance 2. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular sequelae of obesity are not completely understood. Proposed hypotheses include an increase in intra-abdominal pressure and the role of adipose tissue as an active endocrine and paracrine organ 3. Adipocytes secrete numerous hormones, peptides and other molecules that affect metabolism, vascular function and glucose homeostasis 4. An array of pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted by adipose tissue contribute to a state of low-grade inflammation, which possibly mediates the links between obesity, CVD and insulin resistance 5, 6.

Novel risk factors implicated in the cardiometabolic syndrome include lipoproteins and the sphingolipid ceramide species 7. Sphingolipid, from which ceramides are derived, are major regulators of lipid metabolism; their synthesis has been shown to upregulate the expression of the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) which directly activate at least 33 lipid-related genes 8. Lipoproteins, a pseudomicellar structure comprised of a phospholipid and protein coat surrounding a core rich in cholesterol and triglycerides, transfer lipids from sites of production (e.g. liver and gut) to tissues where they are utilized for energy, membrane assembly, or hormone synthesis. Their fundamental protein components, apolipoproteins, are critical to the structure and function of lipoproteins – specifically for directing their metabolic fate 9. ApoA-1 and ApoB100 are the structural proteins responsible for transporting high density lipoproteins (HDL) and the very low density lipoprotein (VLDL)-low density lipoprotein (LDL) spectrum, respectively. ApoA-1 lipoproteins mediate reverse cholesterol transport, transferring excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues back to the liver where it can be excreted in bile. ApoB100 containing lipoproteins transport VLDL and remnant particles from liver and gut generally, to sites of utilization.

Elevated plasma ceramides and apolipoproteins are implicated in the development of atherosclerotic CVD through several mechanisms 10. In addition to their involvement in the transcriptional regulation of lipogenesis, increased ceramide and shpingomyelin (SM) content in oxidized remnant lipoproteins enhances their susceptibility for aggregation and retention in arterial walls. The ceramide metabolite, SM, reduces clearance of remnant lipoproteins by blocking access to lipoprotein lipase and Apolipoprotein E (ApoE), a ligand for LDL receptor binding 11. Inhibition of ceramide biosynthesis by myriocin, in an ApoE knockout murine model of atherosclerosis, significantly reduced atherosclerosis and improved hepatic and plasma lipids and lipoprotein levels 12. ApoA-1 levels have been inversely related to the risk of cardiac events such as myocardial infarction 13. The ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio is one of the strongest novel risk factors for coronary heart disease and may be more informative than actual levels of either lipoprotein alone 13, 14. Abnormal levels of adipose tissue and/or plasma ceramides, ApoB100 and the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio have also been reported in obese individuals, and correlate with the degree of insulin resistance and inflammation 15, 16.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for obesity and its associated state of metabolic disarray. The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is the most commonly performed and successful bariatric procedure in the US at present. In addition to substantial weight loss, RYGB leads to dramatic improvements in glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and CVD risk 17. However, the mechanisms underlying such effects have not been fully elucidated. We recently reported that improvements in the proinflammatory state and insulin sensitivity seen after gastric bypass surgery may be partly mediated by changes in ceramide levels 18. We now hypothesize that the beneficial effect of RYGB on cardiovascular risk is related to a ceramide-mediated improvement in lipoprotein profile, specifically to changes in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio. The primary aim of this study was to serially quantify apolipoproteins (ApoA-1 and ApoB100) and individual ceramide subspecies in the circulation of severely obese patients undergoing RYGB. We examined the relationship between apolipoproteins, the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio, and plasma ceramide levels, with clinical and laboratory-based indicators of cardiovascular risk pre- and postoperatively.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

This prospective longitudinal study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and all patients gave written informed consent. Our study cohort consisted of 10 severely obese patients undergoing laparoscopic RYGB, on the basis that they met the criteria for bariatric surgery as outlined by the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel report of 1991 19. Individuals with known autoimmune disease, cancer, thrombotic disorders, and valvular heart disease were excluded, as were those who were unable or unwilling to cooperate with post-operative follow-up. Consenting participants were evaluated at three time-points; preoperatively, 3 and 6 months post-RYGB. Each evaluation comprised a clinical and physical review, anthropometric measurements, cardiovascular risk assessment, and blood sampling for measurement of biochemical, metabolic, and inflammatory biomarkers. Blood samples were collected after a 12-hour fast using evacuated blood collection tubes containing EDTA. Laparoscopic RYGB was performed as described previously 20

Analytical Measurements

Fasting blood samples were analyzed for concentrations of the following biochemical markers: fasting plasma glucose, insulin, free fatty acids, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, ceramide subspecies (C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, C18:1, C20:0, C24:0, C24:1) and the apolipoproteins ApoA-1 and ApoB100. Ceramide species were quantified in prepared plasma samples by HPLC on-line electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry, as previously described 21. Ceramide subspecies were quantified (nmol/ml) using calibration curves and the ratios of the integrated peak areas of ceramide subspecies and internal standards. Total measured ceramide was calculated from the sum of C14:0, C16:0, C18:1, C18:0, C20:0, C24:0 and C24:1 ceramide subspecies. Plasma levels of ApoB100 and ApoA-1 were measured using the human apolipoprotein assay kit (#APO-62 K) and protocol available from Millipore (Billerica, MA), on a MILLIPLEX® MAP platform, according to the vendor’s guidelines.

Clinical measurements

Vascular reactivity was measured as a surrogate marker for endothelial function, by means of a brachial artery reactivity test at baseline and at the 6-month postoperative assessment 22. In this assessment, a normal response of the brachial artery to reactive hyperemia is 10–15% vasodilation; impaired relaxation (<10%) suggests subclinical atherosclerotic disease 23. Insulin resistance was estimated using the previously validated homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance 24. Cardiovascular risk was determined at baseline and at both time points post-operatively using the gender specific Framingham Coronary Heart Disease risk score developed by Wilson et al 25.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were perfor med using PASW Statistics programme version 18 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons over time for the apolipoproteins, ceramide species, and key outcome variables was performed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), and associations between variables were determined using Pearson’s correlation analyses. In all tests, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and surgical outcome

Ten patients (9 female, mean age for the group 48.6± 9.6 yrs and preoperative BMI 48.5±5.8 kg/m2) were included in this study. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are outlined in Table 1. All patients had at least one obesity-related comorbidity, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus and obstructive sleep apnea. Postoperative weight loss is also documented in Table 1; body weight and BMI had decreased significantly by 6 months postoperatively. The percent of excess weight loss (%EWL) at 3 and 6 months was 38.2±6.8% and 51.3±10.0%, respectively. Of three patients with diabetes mellitus, two experienced remission within the first 3 months postoperatively, as defined by the American Diabetes Association’s criteria of normal glycemic measures with no active pharmacologic therapy 26. The other diabetic patient had an improvement in glycemic indices and reduction in oral hypoglycemic requirements at 3 and 6 months post-RYGB.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and surgical outcomes [Mean ± SD]

| Pre-op | 3 months post- | 6 months post- | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGB | RYGB | |||

| N | 10 | 10 | 10 | - |

| Age, years | 48.6 ± 9.6 | - | - | - |

| Gender %M/F | 10/90 | - | - | - |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 30% | 10% | 10% | 0.107 |

| Hypertension | 90% | 50% | 50% | 0.292 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 80% | 50% | 40% | 0.197 |

| Obstructive Sleep | 30% | 10% | 0% | - |

| Weight (lb) | 294.2 ± 61.4 | 237.8 ± 55.8 | 217.7 ± 52.1 | 0.015 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 48.5 ± 5.8 | 38.8 ± 5.0 ^ | 35.7 ± 5.0 | <0.001 |

p-values represent the significance of the difference between preoperative and 6 month post-RYGB values.

The difference between preoperative and 3 month post-RYGB values is significant

BMI, Body mass index

Changes in metabolic indices, insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk post-RYGB

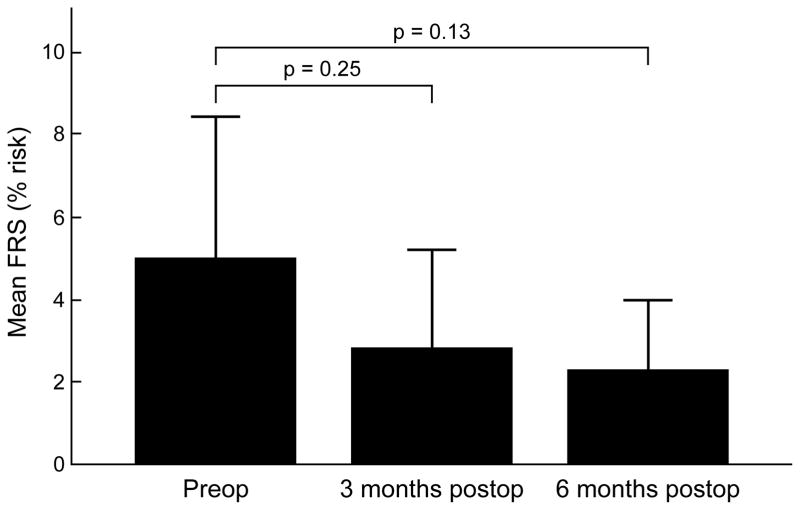

We have previously reported significant decreases in a variety of metabolic indices and proinflammatory markers after gastric bypass, observed in a larger cohort of patients inclusive of the ten current study participants 17. Specific results for the present group of patients are illustrated in Table 2. Herein, we again observed significant decreases in levels of fasting plasma insulin, free fatty acids, total cholesterol, low-density cholesterol, and HOMA-IR at both 3 and 6 months postoperatively. The mean % increase in brachial artery reactivity seen in these ten patients at 6 months was 4.2±10.1%. Although this change did not meet statistical significance (p=0.17), it is suggestive of an improvement in endothelial function. Ten-year cardiovascular risk, as measured by the FRS, decreased with surgical-induced weight loss. At 3 months the FRS had decreased by 33.5% and at 6 months by 43.6%, however these decreases were not statistically significant (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Metabolic markers, endothelial reactivity and Framingham risk score pre- and postoperatively [Mean ± SD]

| Pre-op | 3 months post- | 6 months post- | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGB | RYGB | |||

| N | 10 | 10 | 10 | - |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 0.33 |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 103.4 ± 42.0 | 91.9 ± 32.9 | 85.4 ± 19.4 | 0.24 |

| FPI (pg/ml) | 630.9 ± 389.5 | 338.2 ± 207.5 ^ | 302.7 ± 118.7 | 0.03 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 ^ | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.01 |

| FFA (mmol/l) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 ^ | 0.3 ± 0.2 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol | 209.6 ± 38.0 | 172.9 ± 35.9 ^ | 173.7 ± 41.8 | 0.06 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 130.5 ± 33.7 | 102.3 ± 25.9 ^ | 94.9 ± 28.0 | 0.02 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 50.0 ± 18.0 | 47.7 ± 14.4 | 59.2 ± 23.1 | 0.34 |

| Tg (mg/dl) | 144.9 ± 53.1 | 114.8 ± 39.4 | 115.1 ± 49.6 | 0.21 |

| Total ceramides | 8.8 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 0.05 |

| C14:0 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.25 |

| C16:0 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.06 |

| C18:0 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.04 |

| C18:1 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.13 |

| C20:0 | 0.38 ± 0.12 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.07 |

| C24:0 | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 0.21 |

| C24:1 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.67 |

| ApoA-1 (×106, ng/mL) | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 0.56 |

| ApoB100 (×106, ng/mL) | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 0.6 ^ | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 0.01 |

| ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio | 0.92 ± 0.3 | 0.78 ± 0.2 | 0.66 ± 0.2 | 0.04 |

| BART | 20.1 ± 6.9 % | 24.3 ± 6.3 % | 0.17 | |

| Framingham risk | 5.0 ± 4.4 % | 2.8 ± 3.1 % | 2.3 ± 2.2 % | 0.13 |

p-values represent the significance of the difference between preoperative and 6 month post-RYGB values.

The difference between preoperative and 3 month post-RYGB values is also significant

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FPI, fasting plasma insulin; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic model of assessment of insulin resistance; TG, triglycerides; FFA, fasting plasma free fatty acids; BART, Brachial artery reactivity testing; FRS, Framingham risk score (10 year risk)

Figure 1.

Framingham risk score (FRS) at baseline (preoperatively), 3 months and 6 months post RYGB.

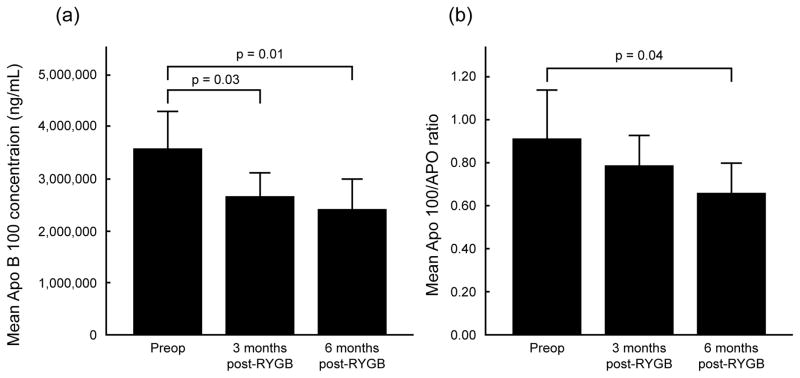

We also recently reported that plasma ceramide levels decrease post-RYGB, and that the decrease in total ceramide levels correlate with increased insulin sensitivity 18. Additionally, in this study we observed a significant decrease in levels of ApoB100 lipoprotein (average decreases of 22.9% at 3 months and 32.1% at 6 months, p= 0.01 and p=0.02, respectively) and a corresponding decrease in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio (average decreases of 4.5% at 3 months and 22.5% at 6 months, p= 0.27 and p=0.04, respectively), both of which are considered novel cardiovascular risk factors (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change in levels of apolipoprotein (Apo) B100 (a) and in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio (b) at 3 and 6 months after RYGB.

Correlation of apolipoprotein changes with ceramide levels and cardiovascular risk postoperatively

At 3 months post-RYGB, the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio correlated significantly with levels of total ceramides and C18:0, C18:1, C20:0, C24:0 ceramide subspecies (Pearson’s correlation coefficients illustrated in Table 3). At 6 months, there remained a trend toward decreasing ceramide levels in association with a continued decrease in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio although the correlations were no longer significant at this time point. The percent change in ApoB100 and in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio at both time points also showed interesting correlations with ceramide subspecies, and lipid levels. At 3 months, the % change in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio correlated with the % change in C18:1 (r=0.68, p=0.03), while the correlation with changes in total ceramide levels neared significance (r=0.56, p=0.09). The postoperative change in ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio also correlated significantly with the changes in total cholesterol, LDL, and triglyceride levels (p=0.01, p=0.01, and p=0.002, respectively). Furthermore, the change in this ratio correlated negatively with the % EWL (r= −0.62, p=0.05) reflecting the fact that the greater the weight loss postoperatively, the greater the decrease in ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio. At 6 months, the change in the apolipoprotein ratio correlated with the % change in C14:0 (r=0.69, p=0.03), and the % change in ApoB100 alone correlated with the change in triglyceride levels.

Table 3.

Correlation of ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio with plasma ceramide levels at 3 and 6 months post-RYGB

| Correlation with ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio: | Total ceramides | C14:0 | C16:0 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C20:0 | C24:0 | C24:1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months post-RYGB | ||||||||

| Pearson’s correlation | 0.86 | −0.33 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.60 |

| coefficient p-value | <0.01 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| 6 months post-RYGB | ||||||||

| Pearson’s correlation | 0.48 | −0.03 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.35 | −0.04 |

| coefficient p-value | 0.16 | 0.94 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.91 |

Changes in the apolipoprotein ratio and ceramide levels after surgery were observed to correlate with endothelial reactivity, and with clinical indicators of cardiovascular risk and insulin sensitivity. At 6 months post-RYGB, the decrease in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio correlated inversely with brachial artery reactivity (r=−0.72, p=0.02). The % change in FRS was closely associated with the % change in total ceramides (r=0.67, p=0.04), C14:0 (r=0.63, p=0.07), C18:1 (r=0.63, p=0.07), and C24:1 (r=0.66, p=0.05). Finally, the % change in total ceramides correlated with the % change in HOMA-IR (r=0.71, p=0.02), and with an improvement in BART (r=−0.74, p=0.03).

Discussion

This prospective study, examining the change in novel cardiovascular biomarkers in a bariatric patient population, is the first to explore the potential role of apolipoproteins and ceramides in mediating the cardiometabolic benefits of weight loss surgery. Building on previous reports from our research group which demonstrated that bariatric surgery induces significant reductions in plasma ceramides, pro-inflammatory markers, and other indicators of CVD 17,18, we now present preliminary data demonstrating that apolipoproteins are also significantly altered post-RYGB. We believe the changes in ApoB100 and the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio are likely to be mediated by the simultaneous decrease in ceramide production, given the significant correlations observed between these lipid moieties as well as with other risk factors for CVD. In addition to observing decreases in absolute values of ApoB100, the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio, and ceramides, the fact that we observed significant correlations between the percent changes in both apolipoproteins and ceramide levels strengthens the case that the intervention (RYGB) was responsible for alterations in these parameters. Baseline physiology levels often vary widely between individuals, particularly among obese individuals with states of metabolic disarray. Using the percentage change in parameters from baseline can therefore be a more robust method of analysis. We also observed that the postoperative percent change in the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio correlated with the percent change in total cholesterol, LDL, and TG levels, and with the improvement in patient’s endothelial reactivity as measured by BART. These interesting associations lead us to believe that gastric bypass was primarily responsible for reducing the risk of atherosclerotic CVD, as indicated by alterations in these risk factors, and that apolipoproteins and the ceramide sphingolipids could be the potential mediators’ of these effects.

It is well known that weight loss induces favorable changes in cholesterol levels, blood pressure, glycemic indices and weight-related diseases. Such effects are particularly evident following the dramatic weight loss that occurs after bariatric procedures such as RYGB. Accumulating evidence also suggests that surgically-induced weight loss is associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality, and overall mortality 27. However, the precise mechanisms underlying the reduction in CVD risk following weight loss are incompletely understood. Postulated mechanisms of cardiovascular protection include a decrease in inflammation, decreased intra-abdominal pressure as a result of reduced visceral fat, and improved endothelial function 28, 29. We hypothesized that changes in lipid metabolism also play a part in effecting the cardiovascular benefits of weight loss and bariatric surgery. Kullberg et al have previously demonstrated that weight loss resulting from a low-calorie diet or gastric bypass surgery resulted in significant lipid mobilization as soon as one month after intervention; the magnitude of these effects was greater among surgical patients despite equivalent weight loss 30. Caloric restriction and loss of adipose tissue mass has been shown to cause decreases in hepatic lipogenesis, hepatic VLDL-TG secretion, hepatic fat content, gene expression of hepatic chemokines, and hepatic fibrogenesis 31. It has also been shown previously that apolipoprotein secretion changes with weight loss, although data in this field is less consistent 32. Cholesterol levels have a direct effect on regulation of lipoprotein levels; individuals with hypercholesterolemia for example have increased Apo-B containing lipoproteins consequent in part to decreased clearance of particles by receptors 9. It is not surprising then that interventions such as bariatric surgery, which induce changes in cholesterol levels through weight loss or other mechanisms, would also affect lipoprotein concentrations. It is well reported that changes in an individual’s lipid profile affects CVD risk, and indeed mortality 33. However, this is the first time that an association has been identified between post-bariatric surgery changes in apolipoprotein levels, ceramide sphingolipids, and reduction in CVD risk.

Several findings from this and other reports 30 suggest that improvements in lipid metabolism after gastric bypass surgery may be weight-independent effects of the surgery, specifically due to its malabsorptive component. Evidence to support this includes the fact that changes observed in lipids, apolipoproteins, and ceramide levels occur early after surgery, even before significant weight loss occurs. Furthermore, patients with non-surgical induced malabsorptive diseases are known to have abnormal lipid metabolism and low plasma cholesterol 34. Interruption of the entero-hepatic cycle of bile acids and a decrease in the absorption of cholesterol result in enhanced bile acid synthesis from cholesterol, which stimulates uptake of cholesterol rich lipoproteins by the liver 34. These effects may partly explain the changes we observed in circulating apolipoprotein and ceramide levels post-RYGB.

The regulation of lipid metabolism by sphingolipids is known to occur through their regulation of genes that synthesize key proteins of cholesterol, phospholipid and fatty acid metabolism 35. Worgall et al have also demonstrated that ceramides correlate with increased transcription and expression of genes and proteins that mediate cholesterol metabolism, including the SREBP family of transcriptional factors. Although there is no direct evidence to date linking ceramide and lipoprotein levels, it is intuitive that as ceramides affect cholesterol levels at the transcriptional stage, then lipoprotein levels would also reflect properties of ceramide and sphingolipid metabolism. Sphingolipids have been indicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of metabolic diseases, including obesity and its associated states of insulin resistance and atherosclerosis 16. In fact sphingolipid metabolism, of which ceramides are a product, is activated by the constellation of proinflammatory markers and adipokines secreted form visceral fat 16. Ceramide signaling has also been shown to induce particular inflammatory responses in atherosclerotic lesions, such as smooth muscle cell proliferation. Additionally, these sphingolipid metabolites have been shown to contribute to the instability and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques 16. Decreasing the activity of sphingolipid and ceramide pathways, through weight loss or weight independent effects of gastric bypass surgery, may therefore be an important mechanism in CVD risk reduction. Data from this study, such as the inverse correlation observed between the ApoB100/ApoA-1 ratio and brachial artery reactivity at 6 months postoperatively, as well as the strong correlations between the percent change in total ceramide levels and the improvement in brachial artery reactivity and Framingham risk scores after gastric bypass, supports this hypothesis.

This pilot study had some limitations, particularly the small subject numbers. It is unlikely to be powered sufficiently to detect the relevance of much smaller changes in lipoprotein and ceramide levels on CVD risk. Larger prospective studies are necessary to further extrapolate the magnitude of the effect of sphingolipid metabolism and lipoprotein levels on atherosclerotic disease, and the extent of the effect of bariatric surgery on altering that relationship. Further, a correlation between variables does not prove causality; additional mechanistic studies are needed to determine if this link is indeed causative or purely associative.

Conclusion

This study is the first to show a relationship between altered ceramide levels after bariatric surgery in morbidly obese patients, and decreased risk factors for CVD such as lipoprotein and lipid levels, brachial artery reactivity, and the Framingham risk score for heart disease. The improvements observed in cardiovascular risk parameters as soon as 3–6 months after gastric bypass further highlight the major benefits of bariatric surgery, and support the development and application of surgical approaches for the treatment of obesity and for CVD risk reduction.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the surgical nursing staff of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, and the patients who volunteered for the advancement of research. This work was partially supported by a research grant from SAGES (SAB), National Institutes of Health grants R21 RR025346 (TK), RO1 DK089547, RO1 AG12834 (JPK), and Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Programs Grant K12 RR023264 (SRK).

Footnotes

Disclosures/Conflicts of interest

Dr. Brethauer is a speaker, consultant, and scientific advisory board member for Ethicon Endo-Surgery, speaker for Covidien, and receives research support from Bard/Davol. Dr. Schauer’s disclosures include: Ethicon Endo-Surgery: consultant, scientific advisory board member, research support; Remedy MD: board of directors; Stryker Endoscopy: scientific advisory board, educational grant; Bard/Davol: scientific advisory board, consultant; Gore: consultant, educational grant; Baxter: educational grant; Barosense, Surgiquest, Cardinal/Snowden Pencer: scientific advisory board; Covidien: educational grant; Allergan: educational grant; Surgical Excellence LLC: board of directors. Hazel Huang and Drs. Heneghan, Eldar, Gatmaitan, Kashyap, Kirwan, and Gornik have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castro JP, El-Atat FA, McFarlane SI, Aneja A, Sowers JR. Cardiometabolic syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5:393–401. doi: 10.1007/s11906-003-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Felton WL, 3rd, Nakatsuka M, Sismanis A. Increased intra-abdominal pressure and cardiac filling pressures in obesity-associated pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1997;49:507–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunzell JD, Hokanson JE. Dyslipidemia of central obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 1999;22 (Suppl 3):C10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazquez LA, Pazos F, Berrazueta JR, et al. Effects of changes in body weight and insulin resistance on inflammation and endothelial function in morbid obesity after bariatric surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:316–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly KR, Kashyap SR, O’Leary VB, Major J, Schauer PR, Kirwan JP. Retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) protein expression is increased in omental adipose tissue of severely obese patients. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:663–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident coronary heart disease in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2004;109:837–42. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116763.91992.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horton JD, Shah NA, Warrington JA, et al. Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12027–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534923100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcovina S, Packard CJ. Measurement and meaning of apolipoprotein AI and apolipoprotein B plasma levels. J Intern Med. 2006;259:437–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holewijn S, den Heijer M, Swinkels DW, Stalenhoef AF, de Graaf J. Apolipoprotein B, non-HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol for identifying individuals at increased cardiovascular risk. J Intern Med. 2010;268:567–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arimoto I, Saito H, Kawashima Y, Miyajima K, Handa T. Effects of sphingomyelin and cholesterol on lipoprotein lipase-mediated lipolysis in lipid emulsions. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hojjati MR, Li Z, Zhou H, et al. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10284–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walldius G, Jungner I, Holme I, Aastveit AH, Kolar W, Steiner E. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:2026–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walldius G, Jungner I, Aastveit AH, Holme I, Furberg CD, Sniderman AD. The apoB/apoA-I ratio is better than the cholesterol ratios to estimate the balance between plasma proatherogenic and antiatherogenic lipoproteins and to predict coronary risk. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:1355–63. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatmaitan P, Huang H, Talarico J, et al. Pancreatic islet isolation after gastric bypass in a rat model: technique and initial results for a promising research tool. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:532–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samad F, Hester KD, Yang G, Hannun YA, Bielawski J. Altered adipose and plasma sphingolipid metabolism in obesity: a potential mechanism for cardiovascular and metabolic risk. Diabetes. 2006;55:2579–87. doi: 10.2337/db06-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brethauer SA, Heneghan HM, Eldar S, et al. Early effects of gastric bypass on endothelial function, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk in obese patients. Surg Endosc. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1620-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H, Kasumov T, Gatmaitan P, et al. Gastric Bypass Surgery Reduces Plasma Ceramide Subspecies and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Severely Obese Patients. Obesity. 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.107. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2003;238:467–84. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089851.41115.1b. discussion 84–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasumov T, Huang H, Chung YM, Zhang R, McCullough AJ, Kirwan JP. Quantification of ceramide species in biological samples by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2010;401:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuvin JT, Patel AR, Sliney KA, et al. Peripheral vascular endothelial function testing as a noninvasive indicator of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1843–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01657-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takase B, Uehata A, Akima T, et al. Endothelium-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation in coronary and brachial arteries in suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1535–9. A7–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buse JB, Caprio S, Cefalu WT, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2133–5. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koh KK, Oh PC, Quon MJ. Does reversal of oxidative stress and inflammation provide vascular protection? Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:649–59. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosito GA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:605–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kullberg J, Sundbom M, Haenni A, et al. Gastric bypass promotes more lipid mobilization than a similar weight loss induced by low-calorie diet. J Obes. 2011;2011:959601. doi: 10.1155/2011/959601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein S, Mittendorfer B, Eagon JC, et al. Gastric bypass surgery improves metabolic and hepatic abnormalities associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1564–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Culnan DM, Cooney RN, Stanley B, Lynch CJ. Apolipoprotein A-IV, a putative satiety/antiatherogenic factor, rises after gastric bypass. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:46–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor F, Ward K, Moore TH, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD004816. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cachefo A, Boucher P, Dusserre E, Bouletreau P, Beylot M, Chambrier C. Stimulation of cholesterol synthesis and hepatic lipogenesis in patients with severe malabsorption. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1349–54. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300030-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worgall TS. Regulation of lipid metabolism by sphingolipids. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:371–85. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8830-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]