Abstract

Background

The difficulties of recruiting individuals into mental health trials are well documented. Few studies have collected information from those declining to take part in research, in order to understand the reasons behind this decision.

Aim

To explore patients' reasons for declining to be contacted about a study of the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy as a treatment for depression.

Design and setting

Questionnaire and telephone interview in general practices in England and Scotland.

Method

Patients completed a short questionnaire about their reasons for not taking part in research. Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with a purposive sample to further explore reasons for declining.

Results

Of 4552 patients responding to an initial invitation to participate in research involving a talking therapy, 1642 (36%) declined contact. The most commonly selected reasons for declining were that patients did not want to take part in a research study (n = 951) and/or did not want to have a talking therapy (n = 688) (more than one response was possible). Of the decliners, 451 patients agreed to an interview about why they declined. Telephone interviews were completed with 25 patients. Qualitative analysis of the interview data indicated four main themes regarding reasons for non-participation: previous counselling experiences, negative feelings about the therapeutic encounter, perceived ineligibility, and misunderstandings about the research.

Conclusion

Collecting information about those who decline to take part in research provides information on the acceptability of the treatment being studied. It can also highlight concerns and misconceptions about the intervention and research, which can be addressed by researchers or recruiting GPs. This may improve recruitment to studies and thus ultimately increase the evidence base.

Keywords: cognitive behaviour therapy, depression, non-participation, qualitative research/mixed methods, randomised controlled trials

INTRODUCTION

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for evaluating the effectiveness of healthcare interventions. Poor recruitment reduces the power of the study,1 can lead to early closure of the study,2,3 or limit the generalisability of results.4 If there is a high non-participation rate, this may also lead to sampling bias, delays in completion, and increased study costs.5–10

Studies have identified factors affecting participation in RCTs by exploring motivations for participation, such as altruism.8,11,12 Few studies have investigated patients' reasons for not taking part in research, possibly because of the potential ethical and practical difficulties in accessing people who have already declined.12,13 Studies have focused on describing demographic characteristics associated with non-participation, such as educational level or age,13–15 but there is little consistency in findings. In addition, the majority of research into why individuals do not participate has been quantitative,2,4 providing limited insight into the views of those who have declined to take part, and the existing qualitative literature has largely focused on concerns about randomisation.16

The evidence on non-participation of different patient groups and in different settings needs to be expanded.12 Reasons for non-participation may be specific to a particular research topic or population.13 Particular difficulties are reported in relation to recruiting primary care patients into mental health trials.17–22 These include GPs' concerns about protecting the vulnerable patient and introducing a request for research participation within a potentially sensitive consultation.17,20 For patients, non-participation can be driven by preference for or against a particular treatment, or uncertainty related to the treatment or research process.2,19

Many patients with depression express a preference for ‘talking therapies’,23–26 but while access to psychological therapies is improving,27 there is little evidence that the demand for psychological therapies will be as high as has been suggested.28 The objective of this study was to explore patients' reasons for declining to be contacted about a study of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) as a treatment for depression in the context of the CoBalT study. This is a multicentre RCT investigating the effectiveness of CBT given in addition to usual GP care (that includes antidepressant medication) in reducing depressive symptoms in primary care patients with treatment-resistant depression, compared to usual GP care alone.

METHOD

The CoBalT study

Participants were recruited to the CoBalT study through 73 GP practices in Bristol, Exeter, and Glasgow and surrounding areas. Eligible patients were those aged 18–75 years, currently taking antidepressants, who had done so for at least 6 weeks at an adequate dose, and who had adhered to their medication, had a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)29 score of >13, and met International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 criteria for depression assessed using the Clinical Interview Schedule — revised version.30

How this fits in

Particular difficulties are reported in relation to recruiting primary care patients into mental health trials but little is known about why people do not take part in research. Using a mixed-methods approach, this study identified patients' reasons for declining contact in a study about the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Patients declined due to: previous negative experiences of talking therapy; misgivings about the therapeutic encounter because they considered themselves ineligible or misunderstood the treatment intervention. These concerns, if identified, could be addressed by the research team or GP, to improve recruitment to studies.

Recruitment to the study and data collection

While a small number of individuals were referred directly to the study by collaborating GPs, the majority were identified through a search of the GP practices' computerised records. This search identified those receiving repeat prescriptions of antidepressant medication. Potentially eligible patients were mailed an invitation letter on GP-headed notepaper asking for their consent to be contacted by the research team about a study looking at the effectiveness of a type of talking therapy (CBT) as a treatment for depression, given in addition to antidepressants. An information leaflet about the study accompanied this letter. Those who agreed to contact were mailed a questionnaire asking about their depressive symptoms and use of antidepressant medication, in order to identify those with treatment-resistant depression. A reminder letter was sent after 2 weeks.

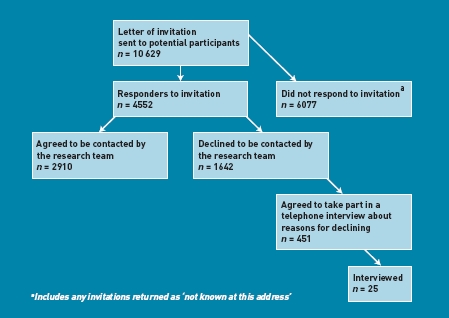

The number of patients mailed a letter inviting them to take part in the CoBalT study by their GP, those declining contact, and the number who agreed to be interviewed about their reasons for not taking part are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of response to letter of invitation to participate in study.

The invitation letter included a short questionnaire. Those who did not want to be contacted were asked to complete and return this directly to the research team. This questionnaire asked for information on the patient's age, sex, and reason(s) for non-participation, using a series of five closed responses and one open ‘other’ category (Box 1). Individuals were asked to tick all boxes that applied and indicate whether they would be willing to take part in a short telephone interview to discuss their reasons for declining participation. The questionnaire was brief, to maximise the likely response. These data were collected throughout the recruitment period for the trial (January 2009 to September 2010).

Box 1. Decliner questionnaire: reasons for not wanting to take part in CoBalT

I do not want to take part in a research study

I am not depressed

I do not want to have talking therapy

I am too busy

I am not taking antidepressants

If other, please specify: ……………………………

In-depth interviews were held with a subgroup of those who had returned the decliner questionnaire and indicated willingness to take part in a telephone interview. Recruitment to the qualitative study was an ongoing process conducted as questionnaires were returned to the research team, to ensure individuals were interviewed within 1 month of declining to be contacted further about the trial. This was done to minimise recall bias. Researchers who received completed decliner questionnaires contacted the researcher responsible for conducting the interviews, to inform her that a questionnaire had been received and to provide the information she needed to purposefully sample potential interviewees. This researcher purposefully sampled individuals who indicated that they did not want to take part in a research study and/or did not want a talking therapy. Ticking ‘other reason’ was not part of the sampling criteria for telephone interviews. It was felt that interviewing these individuals would provide the most insight into what factors regarding the study and intervention were affecting recruitment. The researcher also aimed for maximum variation in relation to study site, patient age, and sex. Interviews were carried out until data saturation was reached (n = 25)

The telephone interviews were conducted between March and September 2009. Interviews were carried out early in the trial, ensuring that problems perceived by patients regarding the study or intervention could be fed back and changes made to the invitation letter and patient information leaflet if necessary. A topic guide was used to ensure consistency across the interviews. This guide consisted of a series of open-ended questions that related to a number of topic areas: patient recollection of being approached about the study; clarity and quality of the information they received; understanding of the trial and the interventions; reasons for declining; and their views on talking therapies and CBT. With consent, the interviews were audiorecorded and fully transcribed.

Data analysis

Analysis of the quantitative data was undertaken using Stata (version 11.2). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the age and sex of the potential study participants, and reasons for declining to be contacted. Free-text responses in the box detailing ‘other’ reasons for declining to be contacted were analysed qualitatively, coding for themes and subthemes. Interview transcripts were read and re-read by two researchers, to identify emerging themes and develop a coding frame. Once the coding frame was agreed, each transcript was coded using NVivo, and subthemes within reasons for declining identified. Themes and their content were then discussed between the same two researchers until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Decliners: quantitative findings

Those who responded to the invitation letter from the GP were older (n with available data = 4312, mean age = 50.4 years [standard deviation {SD} = 13.6 years]) than those who did not respond (n = 5809; mean age = 46.0 years [SD = 13.2]; t-test P<0.001). Females were more likely to respond to the invitation to participate than male (responders, n with available data = 4419, n female = 3137 (71.0%) versus non-responders: n = 5967, n female = 4040 (67.7%); χ2 test P<0.001). Among those who responded, those who agreed to be contacted were younger (t-testage P<0.001) than those who declined contact, but there were no differences in sex (χ2 testsex P = 0.180). Females were more likely to agree to be telephoned about their reasons for declining (decliners — agree to telephone interview n = 446, n female = 334 [74.9%] versus decliners — no telephone contact n with available data = 1166, n female = 791 [67.8%]; χ2 test P = 0.006). There were no differences in age between those who did or did not agree to take part in a telephone interview (agreed to telephone interview, n with available data = 427, mean age = 53.5 years [SD = 13.2 years] versus not agreed to telephone interview, n = 1138, mean age = 54.5 years [SD = 12.8]; t-test P = 0.160) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age and sex of those approached to take part in the studya

| Responders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Non-responders | Agreed to contact | Declined contact | Agreed to take part in telephone interview about reasons for decliningb |

| Mean age, years, (SD) | 46.0 (13.2) n = 5809 | 48.2 (13.5) n = 2747 | 54.2 (12.9) n = 1565 | 53.5 (13.2) n = 427 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 4040 (67.7) n = 5967 | 2012 (71.7) n = 2807 | 1125 (69.8) n = 1612 | 334 (74.9) n = 446 |

SD = standard deviation.

Data on age and sex were not available for all.

Subset of all those who declined (column 4).

Of the 1642 individuals who declined to be contacted by the research team, 1555 gave one or more reasons for declining. Most often, patients stated that they did not want to take part in a research study and/or did not want to have a talking therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reasons for declining to be contacted by the research team

| Reason | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| I don't want to take part in a research study | 951 (61) |

| I do not want to have talking therapy | 688 (44) |

| Other | 531 (34) |

| I am too busy | 311 (20) |

| I am not depressed | 306 (20) |

| I am not taking antidepressants | 98 (6) |

Individuals were able to indicate more than one reason, hence percentages do not add up to 100%.

Thematic analysis of the free-text (‘other reason’) answers showed that these mainly clustered under the following themes: ineligibility (n = 180); current and past counselling (n = 65); managing condition (n = 94); impossible due to condition (n = 53); and feelings about the therapeutic encounter (n = 37) (Box 2), where n = number of responders whose comments endorsed each heading; multiple responses were permitted.

Box 2. ‘Other reason’ main themes

Perceived ineligibility

I am taking antidepressant for hot flushes/OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder)/arthritis/sleep problems/social anxiety/agoraphobia/PMT (premenstrual tension)

Depression a result of disability and chronic pain

Already seeing a counsellor/therapist

Too many health and personal problems

Experiences of previous counselling

I have tried CBT/talking therapy before; not helpful/helpful

On past experience, it would be more stressful

Feeling they were managing their condition

Feel OK on antidepressants

Manageable level — don't want to destabilise

Living with my condition

Unable to take part because of their symptoms

Suffer panic attacks around people

Back and leg problems restrict ability to go far

I find it difficult to go out of my house alone

Negative feelings about the therapeutic encounter

Can't face talking about mental breakdown

Embarassment/shame talking about condition

Talking when feeling really depressed would make me worse

Decliners: qualitative findings

In total, 25 patients were interviewed (Table 3) for between 6 and 20 minutes. The mean age of the interviewees was 52.7 years (SD = 15.9 years).

Table 3.

Characteristics of those interviewed

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Site | |

| Bristol | 9 (36) |

| Exeter | 9 (36) |

| Glasgow | 7 (28) |

| Sex, female | 17 (68) |

| Age, years | |

| 18–39 | 6 (24) |

| 40–59 | 5 (20) |

| 60–75 | 14 (56) |

Reasons for declining

Four main themes emerged when analysing the data regarding reasons for non-participation: previous experience of a talking therapy; feelings about the therapeutic encounter perceived ineligibility; and misunderstandings about the research. Patients were not declining research itself but the study intervention. Most of the patients' explanations fell under the first two themes. Data pertaining to these themes are presented next. Where participants have been quoted, information is provided on their sex, age, and research centre.

Experiences of previous counselling

Nine patients interviewed stated they had declined to take part because they had previously had counselling and found it a negative experience. This was either because they felt it had been ineffective in dealing with their problem, or because the process of disclosure in therapy had caused them to feel uncomfortable; therapists, however, were not mentioned:

‘I've tried talking therapy before and it just didn't work for me basically … as soon as I stopped having it, everything went back to the same to be honest, it just didn't have that long-term effect.’ (Exeter, female 20 years)

‘Many years ago, they called it counselling [and] I wasn't convinced. It just seemed more of a chat to try and look in to my background and what have you and I didn't think that was really hitting the problem properly.’ (Exeter, male 70 years)

‘I've tried it before and I did nae feel comfortable with it … telling people all my family details and things like that, you know what I mean?’ (Glasgow, male 60 years)

Previous counselling experience was not always negative; for example, one patient felt that they had gained all they could from the talking therapy they had had in the past:

‘I just felt like it wasn't something I was particularly interested in at the moment. Having had CBT … I just felt that I had gained what I could from it.’ (Bristol, female 24 years)

Negative feelings about the therapeutic encounter

Seven patients reported that they had declined because of negative associations with the therapeutic encounter. People did not want to ‘rake up the past’, which they saw as likely to worsen their symptoms:

‘I believe it would be helpful for other people, but not for me right at this moment in time, I'm getting, I'm trying to get my life back on track and I, I'm trying to block it [the past] out … I just don't want to go through it at the moment.’ (Bristol, female 41 years)

‘I suppose because I didn't want to bring up old memories … it's like opening up old wounds sort of thing.’ (Bristol, male 53 years)

‘… at the time I didn't want to talk about it because I thought it might bring back the depression again.’ (Exeter, female 69 years)

Others had serious misgivings about therapy due to embarrassment, anxiety, or being a private person with no wish to talk about personal issues:

‘I did think I don't want to do that. I don't want to be, err, go to anyone and speak face-to-face with anyone … about my life and personal things.’ (Exeter, female 69 years)

‘Well, I er, I feel too embarrassed … I don't really talk to many people. I certainly didn't want everyone to know what I'm suffering from.’ (Glasgow, female 63 years)

‘I just … that's one of my things; I just get nervous going and because I didn't have to go I said no. Trying anything new and waiting I get nervous.’ (Glasgow, female 63 years)

Perceived ineligibility to take part in the trial

Five of the patients did not feel they met the eligibility criteria for the trial. They explained they no longer felt depressed or that the situation causing their depression had changed for the better. For some, depression was not their primary cause for concern, as other health conditions were perceived as having more of an impact:

‘I don't believe I'm suffering with depression … I think it is anxiety and I've had no sign of it now for 5 or 6 months since I have been back on this low dose of medication.’ (Bristol, male 68 years)

‘Well at the moment I've got other health problems … and I didn't want to be bothered with any more things to have to sort of connect me with hospitals … I'm diabetic, got asthma, and chronic kidney disease.’ (Bristol, female 63 years)

In these cases, people commonly thought the depression only existed because of their primary ongoing ‘physical’ conditions and, as such, talking therapy would not be of use:

Patient (P): ‘I don't think all the amount of talking in the world will sort of improve my frame of mind you know? I am on antidepressants for years as my conditio n [rheumatoid arthritis] has got worse … erm I mean it's related to my illness really you know from that point of view.’

Interviewer (I): ‘And you think talking to someone wouldn't help?’

P: ‘Not from my point of view, I can't see that it would.’ (Bristol, Female 61 years)

Misunderstandings about the research

Three patients interviewed had found the invitation letter unclear and, in particular, it was presumed that group therapy was being offered:

P: ‘[Declined because] it would it be in a group of people.’

I: ‘No, it wouldn't have been, it would have been one to one.’

P: ‘Oh well, I don't mind doing one to one.’

I: ‘OK and when you got the [invitation] letter, did you open it and immediately think “I don't want to do this” or …’

P: ‘No, I just didn't understand it to start with.’ (Exeter, female 61 years)

‘I presume[d] it would be, like, a group of people discussing their problems etc, and how they felt.’ (Exeter, female 63 years)

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study explored the reasons why patients declined to be contacted when approached about a study of the effectiveness of CBT (in addition to antidepressants) as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression. The initial invitation letter sought permission to mail out a screening questionnaire to determine their potential eligibility. The main reasons for declining to be contacted by the research team at this initial stage were that people did not want talking therapy or to take part in research. Where patients had provided an alternative (free-text) explanation of the decision to decline contact, explanations included ineligibility, past counselling experiences, and feelings about the therapeutic encounter. Qualitative interviews were carried out to provide further insight into quantitative findings.

Patient interviews focused on the nature of the intervention rather than declining research itself. Those who did not want talking therapy referred to a previous negative experience of talking therapy, because either they felt it was ineffective or it made them feel uncomfortable. Patients expressed misgivings about the therapeutic encounter and declined because they did not like the thought of disclosing personal details, and/or they would be anxious about a face-to-face session with a therapist.

Others regarded themselves as ineligible for the trial because they were no longer depressed, the situation causing their depression had changed, or other health conditions were more important and not ‘fixable’ with a talking therapy. Some patients declined as they believed it was group therapy being offered. Sometimes these themes would overlap in accounts, for example, past experience of counselling could negatively influence feelings about the therapeutic encounter. Interview data confirmed and expanded the questionnaire findings. Reasons for non-participation were often complex and did not simply reflect a reluctance to be involved in research.

Strengths and limitations

Few studies have interviewed those who decline to participate in research. A strength of this study was the mixed-methods approach, utilising quantitative and qualitative data to investigate reasons for non-participation, thus providing breadth and depth of information.

Patients who responded to the decliner questionnaire and invitation to participate in a telephone interview about their reasons for non-participation were a self-selected group, which may limit the generalisability of the findings. Generalisability may also be limited due to individuals with strong opinions being more likely to respond, and by the purposeful sampling approach used to identify interviewees. The study mainly interviewed females over the age of 60 years but this reflected the sex and age balance among those who responded and declined. The absence of accounts from younger males is a weakness in the study.

The decliner questionnaire was short, to encourage completion, and information on reasons for non-participation was mainly gathered in relation to five closed-answer questions. Patients were, however, given the opportunity to detail ‘other reasons’, and analysis of the free-text responses was in line with the interview findings.

Interviews were relatively short, possibly due to them being conducted by telephone. However, many patients said they would not have taken part in a face-to-face interview. Well-planned telephone interviews can gather the same material as those held face to face.31

Comparison with existing literature

Unlike previous studies about non-participation,4,7,12–14 this study further explored reasons for declining research contact given in questionnaire form through qualitative interviews. In keeping with previous research,13 the current study's participants were not declining research itself. The findings draw attention to a previously hidden aspect of reported difficulties in recruitment to mental health trials,17–22,32 namely that a prior negative experience of the same (or similar) intervention influences non-participation. The findings that previous talking therapy experiences and concerns about the therapeutic encounter can influence participation also provide a counterbalance to the reported patients' desire for talking therapy;23–26 little is heard about the negative views of such treatments.

The study data support previous studies showing how misunderstandings about the intervention on offer can influence people's decision to participate in research.13 The study findings highlight important concerns that can be actively addressed by clarifying information provided to potential participants, and attending to anxieties about the intervention.

Implications for practice and research

Collecting information about those who decline to take part in research is a relatively simple way to learn about the acceptability of treatments being studied. In pilot studies for large-scale RCTs, gathering such information may be useful in refining recruitment estimates. Researchers recruiting to trials need to be sensitive to the patients' prior experience of the same (or a similar) intervention being studied, their feelings about the intervention, and their views on their potential eligibility. Comorbid physical disease may impact on an individual's perception about the appropriateness of a psychological treatment.

The difficulties of recruiting patients with depression through the GP consultation have been well documented.17–22 This study highlights that it is the nature of the intervention that is the patients' focus when deciding whether to participate. Given the increasing reliance on letters of invitation to participate in research studies sent by collaborating GPs, this study emphasises the need to ensure clarity in the invitation letter and highlights the importance of using a mixed-methods approach to explore why patients refuse to take part in research during the initial recruitment phase. Similarly, when recruitment takes place in the consultation, GPs need to explore patients' reasons for declining to address any concerns or misconceptions about the research. This could increase recruitment to studies and thus ultimately contribute to increasing the evidence base.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients, practitioners and GP surgery staff who took part in this research. We would like to acknowledge additional support that has been provided by the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), Scottish Mental Health Research Network (SMHRN), Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) and Scottish Primary Care Research Network (SPCRN). We would also like to thank those colleagues who contributed to the COBALT study through recruitment and retention of patients or provision of administrative support. Finally, we are grateful to a number of colleagues who have been involved with the CoBalT study as co-applicants but who have not participated in drafting this manuscript: John Campbell, Tim Peters, Debbie Sharp, Sandra Hollinghurst and Bill Jerrom.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme (project number: 06/404/02). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HTA programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the report.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from West Midlands Research Ethics Committee (ref 07/H1208/60) and research governance approval from Bristol, South Gloucestershire, North Somerset, Devon, and Plymouth Teaching Primary Care Trusts and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Community and Mental Health Partnership. The trial is registered under ISRCTN38231611.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Halpern SD, Karlawish JH, Berlin JA. The continuing unethical conduct of underpowered clinical trials. JAMA. 2002;288(3):358–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prescott RJ, Counsell CE, Gillespie WJ, et al. Factors that limit the quality, number and progress of randomised controlled trials. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3(20):1–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sibthorpe BM, Bailie RS, Brady MA, et al. The demise of a planned randomised controlled trial in an urban Aboriginal medical service. Med J Aust. 2002;177(4):222–223. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham NS, Young JM, Solomon MJ. A systematic review of reasons for nonentry of eligible patients into surgical randomized controlled trials. Surgery. 2006;139(4):469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, et al. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(12):1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mapstone J, Elbourne D, Roberts I. Strategies to improve recruitment to research studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub3. MR00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, et al. What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials. 2006;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-9. http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/7/1/9 (accessed 1 Mar 2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fayter D, McDaid C, Ritchie G, et al. Systematic review of barriers, modifiers and benefits involved in participation in cancer clinical trials. York: University of York; 2006. CRD report 31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewison J, Haines A. Overcoming barriers to recruitment in health research. BMJ. 2006;333(7562):300–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7562.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovato LC, Hill K, Hertert S, et al. Recruitment for controlled clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials. 1997;18(4):328–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tallon D, Mulligan J, Wiles N, et al. Involving patients with depression in research: survey of patients' attitudes to participation. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(585):134–141. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X567036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp L, Cotton SC, Alexander L, et al. TOMBOLA group. Reasons for participation and non-participation in a randomized controlled trial: postal questionnaire surveys of women eligible for TOMBOLA (Trial of Management of Borderline and Other Low-grade Abnormal smears) Clin Trials. 2006;3(5):431–442. doi: 10.1177/1740774506070812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams B, Irvine L, McGinnis AR, et al. When ‘no’ might not quite mean ‘no’; the importance of informed and meaningful non-consent: results from a survey of individuals refusing participation in a health-related research project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettersson C, Lindén-Boström M, Eriksson C. Reasons for non-participation in a parental program concerning underage drinking: a mixed method study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:478. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nechuta S, Mudd LM, Biery L, et al. Attitudes of pregnant women towards participation in perinatal research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(5):424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Featherstone K, Donovan JL. ‘Why don't they just tell me straight, why allocate it?’ The struggle to make sense of participating in a randomised controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(5):709–719. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hetherton J, Matheson A, Robson M. Recruitment by GPs during consultations in a primary care randomized controlled trial comparing computerized psychological therapy with clinical psychology and GP care: problems and possible solutions. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2004;5:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairhurst K, Dowrick C. Problems with recruitment in a randomized controlled trial of counselling in general practice: causes and implications. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1996;1(2):77–80. doi: 10.1177/135581969600100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz T, Fisher P, Katz A, Feder G. The feasibility of a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial of homeopathic treatment of depression in general practice. Homeopathy. 2005;94(3):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason VL, Shaw A, Wiles NJ, et al. GPs' experiences of primary care mental health research: a qualitative study of the barriers to recruitment. Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):518–525. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King M, Broster G, Lloyd M, Horder J. Controlled trials in the evaluation of counselling in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44(382):229–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodford J, Farrand P, Bessant M, Williams C. Recruitment into a guided internet based CBT (iCBT) intervention for depression: lesson learnt from the failure of a prevalence recruitment strategy. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(5):641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prins MA, Veerhak PFM, van der Meer K, et al. Primary care patients with anxiety and depression: need for care from the patient's perspective. J Affect Disord. 2009;119(1–3):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwight-Johnson M, Meredith LS, Hickey SC, Wells KB. Influence of patient preference and primary care proclivity for watchful waiting on receipt of depression treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(5):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brody DS, Khaliq AA, Thompson TL. Patients's perspectives on the management of emotional distress in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):403–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health. End of the ‘prozac nation’— more counselling, more therapy, less medication to treat depression. Press release 16 May 2006. http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/releases/43363.php (accessed 1 Mar 2012)

- 28.Layard R. The case for psychological treatment centres. BMJ. 2006;322(7548):1030–1032. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7548.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck A, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd edn. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. manual. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22(2):465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wakefield M. Differences in health estimates using telephone and door-to-door survey methods — a hypothetical exercise. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22(2):223–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt CJ, Shepherd LM, Andrews G. Do doctors know best? Comments on a failed trial. Med J Aust. 2001;174(3):144–146. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]