Abstract

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) constitute a heterogeneous category of soft tissue neoplasia composed mostly of uncommon tumors of diverse histology, different biology and varied outcomes. Substantial developments in immunohistochemistry (IHC), cytogenetics and molecular genetics of STS have caused a significant change in the classification and diagnosis of these tumors with a direct implication for clinical management and prognosis. In this review we discuss newer developments impacting diagnosis and prediction.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Soft tissue, Immunohistochemistry, Grading, Molecular, Pathology

Introduction

A large majority of soft tissue tumors are benign with a very high cure rate after surgical excision. Malignant mesenchymal neoplasms account for <1% of overall human burden of malignant tumors but they are life threatening and pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Close interaction of surgeons, oncologists and surgical pathologists has brought about a significant disease free survival for tumor which previously almost invariably fatal. The overall 5 year survival rate for STS in the limbs is now in order of 65–75%.

WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumors

The WHO classification (2002) of soft tissue tumors incorporates detailed clinical, histological and genetic data. The usual approach to soft tissue tumor classification is by presumed cell lineage. Tumors are categorized into adipocytic, fibroblastic or myofibroblastic, so called fibrohistiocytic, smooth muscle, pericytic, skeletal muscle, vascular, chondro-osseous and lastly “of uncertain differentiation” category.

Further the WHO working group divides STS into four categories: Benign, Intermediate (locally aggressive), Intermediate (metastasizing) and malignant [1, 2]. Benign soft tissue tumors do not recur locally and almost always cured by complete local excision.

Intermediate (locally aggressive) STS recur locally and are associated with an infiltrative locally destructive growth pattern. Lesions in this category do not have any evident potential to metastasize and typically require wide excision to ensure local control. Intermediate (rarely metastasizing) soft tissue tumor as often locally aggressive but in addition show well documented ability to give rise to distant metastasis in occasional cases. The risk of such metastasis is <2% and is not predictable on the basis of histomorphology. Malignant soft tissue tumors have significant risk of distant metastasis (ranging from 20% to almost 100% depending upon histological type and grade) in addition to the potential for locally destructive growth and recurrence [2, 3].

Grading

Unlike with other tumors the staging of STS is largely determined by grade. Unfortunately there is no generally agreed up on scheme for grading STS [4, 5]. The most widely used STS grading systems are French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group (FNCLCC) [6] and National Cancer Institute (NCI) [5]. Both systems have 3 grades and are based on mitotic activity, necrosis and differentiation which correlate well with the prognosis. However in addition to these criteria, the NCI system requires the quantification of cellularity and pleomorphism for certain subtypes of sarcomas which is difficult to determine objectively. The FNCLCC system is easier to use and appears slightly better in predicting prognosis than NCI system [6] (Table 1). The TNM staging system recommends the FNCLCC system but effectively collapses into high grade and low grade [7, 8], which means that FNCLCC grade 2 tumors are considered “high grade” for the purposes of stage grouping.

Table 1.

FNCLCC grading system: definition of parameters

| Tumour Differentiation | |

| Score 1 | Sarcomas closely resembling normal adult mesenchymal tissue (e.g., well differentiated liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma). |

| Score 2 | Sarcomas for which histological typing is certain (e.g. myxoid liposarcoma & conventional leiomyosarcoma) |

| Score 3 | Embryonal and undifferential sarcomas, Pleomorphic sarcomas, synovial sarcomas, osteosarcomas, PNET) |

| Mitotic Count | |

| Score 1 | 0–9 mitoses per 10 HFP* |

| Score 2 | 10–19 mitoses per 10 HFP* |

| Score 3 | ≥20 mitoses per 10 HFP* |

| Tumor Necrosis: determined on histologic sections | |

| Score 0: | No tumor necrosis |

| Score 1: | Less than or equal to 50% tumor necrosis |

| Score 2: | More than 50% tumor necrosis |

| Histological grade | |

| Grade 1 | Total score 2,3 |

| Grade 2 | Total score 4,5 |

| Grade 3 | Total score 6,7,8 |

Grading of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, and epithelioid sarcoma is not recommended [3].

Morphological Categories

While approaching soft tissue tumors the pathologist must look into architectural pattern, appearance of the cells, and the characteristics of the stroma. These categories can lend themselves to the development of a number of different diagnostics categories which can be further differentiated on the basis of morphological features as well as Immunohistochemical characteristics (Table 2).

Table 2.

STS: mophological categories and IHC parameters

| Morphological category | IHC parameters |

|---|---|

| Fascicular Spindle Cell Sarcomas | |

| Fibrosarcoma | Vimentin |

| Leiomyosarcoma | SMA, HHF 35, Calponin, Desmin +/− |

| Spindle cell RMS | Desmin+, Myogenin+ |

| Synovial sarcoma | S-100 +/−, EMA+ |

| MPNST | S-100 +, EMA- |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | CD34+, CD99−, CD31− |

| Myxoid Soft Tissue Sarcomas | |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | MDM 2 +,CD34 +/−, novel IHC antibody to the TLS/EWS-CHOP chimeric oncoproteins |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | Vim +, Synaptophysin +/−, EMA+/− |

| Myxoid DFSP | CD34 |

| Myxoid MFH (myxofibrosarcoma) | CD34 +, HMGA1 and HMGA2 |

| Botryoid Embryonal RMS | Desmin, Myogenin |

| Myxoid leiomyosarcoma | SMA, HHF 35, Desmin, Myogenin |

| Epitheloid Soft Tissue Sarcomas | |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Desmin, SMA |

| Epithelioid sarcoma | CK, EMA, Vimentin, CD34 +/− |

| Epithelioid angiosarcoma | CD31, Factor VIII, CD34, FLI-1 |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma | CD31, Factor VIII, CD34, FLI-1 |

| Extra gastrointestinal stromal tumor | CD117, CD34+/− |

| Malignant Rhabdoid tumor | Polyphenotypic, Loss of INI1 protein |

| Malignant mesothelioma | Calretinin, Thrombomodulin |

| Synovial sarcoma | EMA, Cytokeratin, S100 +/− |

| Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma | Vimentin |

| Clear cell sarcoma | HMB45, Melan1 EWSR1-ATF fusion |

| Round Cell Soft Tissue Sarcomas | |

| Alveolar RMS | Desmin, Myogenin |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of childhood | Polyphenotypic |

| Embryonal RMS | Desmin, Myogenin |

| Extraskeletal ES/PNET | CD99, FLI-1 |

| Round cell liposarcoma | S-100 |

| Small cell osteosarcoma | Vimentin |

| Malignant hemangiopericytoma | CD34 |

| Pleomorphic Sarcomas | |

| Pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma | Vimentin |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | Alpha 1 antitrypsin, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin |

| Pleomorphic liposarcoma | MDM2 and CDK4 |

| Pleomorphic RMS | Desmin, Myogenin |

| Pleomorphic MPNST | S100 |

| Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma | SMA, SMA, Desmin |

| Pleomorphic angiosarcoma | CD31, Factor VIII, CD34, FLI-1 |

| Chondro-Osseous STS | |

| Mesenchymal Chondrosarcoma | S-100 |

| Extra skeletal osteosarcoma | Vimentin |

| Clear Cell Lesions | |

| Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue | S-100, HMB45, NSE, CD57, EWSR1-ATF fusion gene |

| Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor | HMB45 , MelanA+/−, SMA +/− |

Pitfalls in the Diagnosis of STS

Certain reactive processes may mimic sarcomas. Therefore it is important to determine whether the lesion under study is a reactive process or a neoplasm. Some reactive lesions display a distant zonal quality. For example in nodular fascitis and ischemic fascitis one encounters a cuff of proliferating fibroblasts that surround a central hypocellular zone of fibrinoid change. Cells comprising reactive lesions often have the appearance of tissue culture fibroblasts with large vesicular nuclei, prominent nuclei and cytoplasmic basophilia. No atypical mitosis or nuclear atypia is usually seen.

It is not always possible to classify soft tissue tumors precisely based on biopsy material, especially FNA and core needle biopsy specimens. Although pathologists should make every attempt to classify lesions in small biopsy specimens, on occasion stratification into very basic diagnostic categories, such as lymphoma, carcinoma, melanoma, and sarcoma, is all that is possible. In some cases, precise classification is only possible in open biopsies or resection specimens.

Histologic classification of soft tissue tumors is sufficiently complex that, in many cases, it is unreasonable to expect a precise classification of these tumors based on an intraoperative consultation. Intraoperative consultation is useful in assessing if “lesional” tissue is present and in constructing a differential diagnosis that can direct proper resection of tissue. The role of frozen section in STS is limited only to assure the surgeon that he has obtained representative, adequate and viable tissue for diagnosis or to evaluate the margins.

Grading of sarcomas in small needle core biopsies is also frequently erroneous. Inappropriate sampling may lead to high grade lesion being diagnosed as low grade sarcoma. Core biopsy containing necrosis usually implies high grade sarcoma but necrosis should be coagulative and distinguished from hyaline change. Further necrosis reflective of prior therapy or surgical intervention does not upgrade a lesion. Grading becomes unreliable if chemotherapy and radiotherapy is given prior to biopsy [9].

Pathologists must proceed cautiously and consider IHC results in the context of all available data in a given case of soft-tissue tumors and to the demonstrated tendency to aberrant antigen expression in soft-tissue tumors. Pathologists must be aware not only of the typical profile and reported antigenic infidelities of a particular entity, but also of the pitfalls that can be introduced by technical factors, such as tissue processing and fixation as well as the IHC procedures. It is estimated that. IHC in fact adds confusion to the diagnostic process in 5% to 10% of cases [10].

Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Soft Tissue Tumours

With the implementation of immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics and molecular genetic analysis significant changes have been made regarding the classification and diagnosis of STS. These changes are relevant because they have direct implications for clinical management and prognosis. Many new entities have been recognized of which desmoplastic small round cell tumor and intimal sarcomas are examples. Some sarcoma entities lost in importance (e.g., the so-called malignant fibrous histiocytoma, hemangiopericytoma, and fibrosarcoma categories) [3].

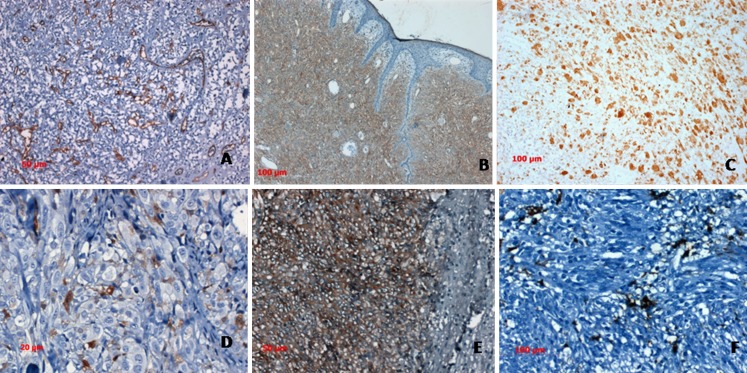

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) plays an important role in STS diagnosis. The diagnostic approach consists in ruling out a nonmesenchymal tumor, followed by trying to define mesenchymal cell lineage. A panel of immunostains, rather than single marker, should always be performed. This approach greatly eliminates the potential for misdiagnosis owing to anomalous expression of antigens (eg, cytokeratin in angiosarcoma) [11]. The routine use of a small, carefully selected panel based on patterns as enumerated in Table 2 is time and cost effective. The extent of sub-categorization of tumors should be driven by clinical relevance. For instance in cases of pleomorphic sarcoma treatment protocols do not discriminate between histologic subtypes with the possible exception of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma(RMS) which may be treated according to an RMS protocol, and Leimyosarcoma for which oncologists often use a specific chemotherapeutic agent. How far should one go with ancillary studies in trying to determine specific lineage and what are the clinical/prognostic implications is a question best answered by need driven requirements of treating oncologists [12] Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

a. Vascular network highlighted in CD 34 stain in a sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma b. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans showing diffuse CD 34 expression c. Diffuse desmin expression in a pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, d. HMB 45 in amelanotic melanoma, e. Diffuse CD117 in GIST and f. Focal SMA in GIST

There is little disagreement over the importance of separating pleomorphic sarcoma from pleomorphic nonmesenchymal malignancies. The main differentials are metastatic sarcomatoid carcinoma, metastatic melanoma, and, in some instances, an unusual hematolymphoid tumor with spindle cell features. The initial battery of IHC markers should always include a broad keratin (pancytokeratin), S100, and vimentin. A positive keratin result indicates primary carcinoma, positive S100 stain should be followed by additional melanoma markers. Hodgkin’s lymphomas, large cell lymphomas including anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and follicular dendritic cell tumor are distinguished using leucocyte common antigen (LCA) and CD30. It is important to remember that some of these tumors may be negative for leukocyte common antigen [11].

Synovial sarcoma is a unique soft tissue sarcoma showing both mesenchymal and epithelial differentiation. Despite its name, it is neither related to nor does it arise from synovial cells. Microscopically, biphasic, monophasic spindle cell, poorly differentiated, calcifying/ossifying and myxoid subtypes have been described [13]. Immunohistochemistry is particularly useful in the diagnosis of the monophasic spindle cell variant, which is more difficult to distinguish from other spindle cell sarcomas on morphologic grounds alone. Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare soft tissue sarcoma showing epithelial differentiation.Cytokeratins and EMA are strongly positive in almost all cases, mostly coexpressed with vimentin. CD34 is positive in about 50% with a strong membranous staining pattern. When positive, this stain is helpful in excluding carcinomas which are CD34 negative.

Despite their similar IHC staining profiles, clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue is clinically and genetically distinct from cutaneous melanoma. Like the latter, it is positive for melanocytic markers S100, HMB-45, and less consistently positive for melan 1. Melanocytic stains are helpful in separating clear cell sarcoma from other soft tissue sarcomas, distinction from cutaneous melanomas is based on tumor morphology, location, or genetic confirmation of the EWSR1-ATF fusion gene, which has been found in clear cell sarcoma but never in cutaneous melanoma.

Immunohistochemistry plays a major role in the differential diagnosis of round cell tumours including Ewing’s sarcoma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors (ES/PNET), alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma , and Merkel cell carcinoma. Strong CD99 membrane immunopositivity is usually seen in most ES/PNET. However, as with most differentiation markers, CD99 tends to be very sensitive but not specific [14].

Pathologists must proceed cautiously and consider IHC results in the context of all available data in a given case being aware of the demonstrated tendency to aberrant antigen expression in soft-tissue tumors. Pathologists must be aware not only of the typical profile and reported antigenic infidelities of a particular entity, but also of the pitfalls that can be introduced by technical factors, such as tissue processing and fixation as well as the IHC procedures. It is estimated that IHC in fact adds confusion to the diagnostic process in 5% to 10% of cases [10].

It is hoped that detection of tumor-specific alterations and validation through genetic analysis on larger samples will lead to development of new IHC antibodies. These new markers detect tumor-specific fusion proteins that are either over expressed or aberrantly expressed as a result of a translocation. Examples of such antibodies are ALK-1, WT-1, and FLI-1.

Molecular Pathology of STS

Molecular genetics of STS has developed at a rapid pace in recent years. Methodological advances including molecular ancillary techniques comprising of a vast array of polymerase chain reaction-based techniques, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), conventional and array-based comparative genomic hybridization, expression arrays, direct genome sequencing, and DNA methylation analysis have allowed better understanding of biology, identified new histogenetic concepts and built up robust diagnostic methods [15]. The more current textbooks including the current World Health Organization edition on tumors of soft tissue and bone reserve specific sections to include recent cytogenetic and molecular data [3]. The majority of sarcomas carry nonspecific genetic changes in a background of a complex karyotype. Many of these alterations have been detected in a small number of cases and confirmatory tests are not yet commercially available. Their diagnostic utility is therefore limited with the exception of some fluorescence in situ hybridization probes, which are being used with increasing frequency, in particular for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma, ES/PNET, and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma.

Soft tissue sarcomas can be divided in two categories: those with simple karyotypes and those with complex karyotypes [15]. Of the soft tissue sarcomas with relatively simple karyotypes, 15–20% bear specific reciprocal translocations which can be used as diagnostic markers. Some others are characterized by specific somatic mutations (e.g., cKIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) [16] or specific amplifications (e.g., MDM2 and CDK4 amplification in the well-differentiated/ dedifferentiated liposarcoma category [17], MYCN amplification in Neuroblastoma, Translocation FKHR (FOXO1A) in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma [18].

The Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1; also known as EWS) represents one of the most commonly involved genes in sarcoma translocations. In fact, it is involved in a broad variety of mesenchymal lesions which includes Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral neuroectodermal tumor, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, clear cell sarcoma, angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, and a subset of myxoid liposarcoma.14 EWSR1 maps on 22q12, and its coding sequence includes 17 exons. 19 EWSR1 rearrangement can be visualized by FISH. However, as in most instances a split-apart approach is used, the results of molecular genetics must be evaluated in context with morphology [19].

Soft tissue sarcomas with complex karyotypes account for about 50% of sarcomas. This sarcoma category includes most of spindle cell/pleomorphic sarcomas (myxofibrosarcoma, pleomorphic liposarcoma, etc.) as well as leiomyosarcomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and many other neoplasms [6]. Sarcomas with non-EWS translocations are spindle, polygonal or small round cell tumours with varying behaviour, which mostly occur in children or young adults. They include synovial sarcoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, infantile fibrosarcoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour [13].

In recent years, a characteristic translocation (X;17) resulting in a ASPL-TPE3 fusion gene has been found in alveolar soft part sarcoma [14, 20]. This fusion gene is not exclusive to alveolar soft part sarcoma but is also present in a pediatric variant of renal cell carcinoma [21]. A new immunohistochemical stain for TFE3 protein has been developed, which detects the over-expressed TFE3 protein in alveolar soft part sarcoma and in other ASPL-TFE3 fusion gene–positive tumors [21].

Apart from the obvious relevance of specific genetic aberrations for establishing a correct diagnosis, which is a prominent prognostic parameter in itself, the importance of the genetic aberrations on clinical outcome of STS is elusive. The currently used prognostication systems rely on relatively crude clinical parameters, such as tumor size, and histopathologic parameters such as morphologic subtype, grade, necrosis, vascular invasion, and growth pattern, all of which suffer from inter-observer variability there is no reason to believe that the pattern of genetic aberrations should be of less importance for the management of soft tissue sarcomas than for that of leukemias and lymphomas, where genomic analyses today constitutes an integral part of the routine diagnostic and prognostic profiling. However, there is clearly a need for further analyses, using cytogenetic as well as high resolution genomic techniques, on larger series of morphologically well-characterized tumors from patients with adequate follow-up to establish the spectrum of aberrations occurring within each type of soft tissue sarcoma, as well as to allow proper evaluation of the prognostic importance of characteristic genomic changes.

GIST is one of the examples in oncopathology where the understanding of the genetics of the tumor has lead to major changes in treatment following the development of specific tyrosine kinase blockers. Resistant mechanisms which develop in the course of the treatment are of keen interest for molecular pathologist and of importance for the patients. The role of predicting response of targeted therapy has been well established for KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors [22].

Biomarker-integrated approaches of targeted therapy for a number of solid tumors have been developed. Chemotherapeutic agents are designed to modulate, inhibit, or otherwise interfere with the function of specific molecular targets that are crucial to the malignancy of tumors, and thereby produce a positive clinical response. The role of the vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor in angiosarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and hemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumor has been evaluated. Several phase II trials in advanced soft tissue sarcoma patients have investigated the efficacy of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, as well as sunitinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib, VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors Although response rates and progression-free survival periods were generally low, several angiosarcoma, epitheloid hemangioendothelioma and hemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumour patients demonstrated response or durable disease stabilization on these therapies [23].

Standard reporting protocol (Table 3) recommended by College of American Pathologists should be used for histological reporting to allow generation of uniform and comprehensive reports [8]. In conclusion the histological diagnosis of STS is complex, and is aided by the use of immunohistochemistry which has been well established in routine pathological practice. The application of molecular and immunohistochemical techniques needs to be under strict protocol and results should be interpreted in the morphological context in order to avoid disastrous mistakes in tumor classification.

Table 3.

Standard reporting system for STS (based on AJCC/UICC/TNM)

| (A) Procedures |

| Biopsy |

| Resection |

| Intralesional resection |

| Marginal resection |

| Wide resection |

| Radical resection |

| Other (Specify) |

| Not specified |

| (B) Tumor site |

| Specify (If known) |

| Not specified |

| (C) Tumor size |

| Greatest dimension _______cm |

| Additional dimension ______cm |

| Cannot be determined |

| (D) Macroscopic Extent of tumor (Select All that apply) |

| Superficial |

| Dermal |

| Subcutaneous |

| Deep |

| Fascial |

| Subfascial |

| Intramuscular |

| Mediastinal |

| Intraabdominal |

| Retroperitoneal |

| Head & neck |

| Other (specify) |

| Cannot be determined |

| (E) Histological type (WHO, classification of STT) |

| Specify |

| Cannot determined |

| (F) Mitotic rate |

| Specify___/10HFP |

| (G) Necrosis |

| Not identified |

| Present-extent _______% |

| (H) Histological Grade (FNCLCC) |

| Grade I |

| Grade II |

| Grade III |

| Ungraded Sarcoma |

| Cannot be determined |

| (I) Margins |

| Positive/Negative |

| Indicate distance from all margins <1.5 cm |

| (J) Lymphovascular Invasion |

| Not identified |

| Present |

| Indeterminate |

| (K) Ancillary studies |

| IHC |

| Cytogenetics |

| Molecular Pathology |

| Others |

| (L) Pre-resection Treatment |

| No therapy |

| CT |

| RT |

| Therapy performed, type not specified |

| Unknown |

| (M) Treatment effect |

| Present specified______ |

| Not specified |

| (N) TNM code |

| (O) Comments |

References

- 1.Hogendoom PCW, Collin F, Daugaard S, et al. Changing concepts in the pathological basis of soft tissue and bone sarcoma tumor. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1644–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher CD (2006) The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology 48(1):3–12 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Oliveira AM, Nascimento AG. Grading in soft tissue tumors: principles and problems. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30(10):543–559. doi: 10.1007/s002560100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coindre JM, Trojani M, Contesso G, et al. Reproducibility of a histopathologic grading system for adult soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 1986;58(2):306–309. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860715)58:2<306::AID-CNCR2820580216>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillou L, Coindre JM, Bonichon F, et al. Comparative study of the National Cancer Institute and French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group Grading Systems in a population of 410 adult patients with soft tissue Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(1):350–362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edge SE, Byrd DR, Carducci MA, Compton CC, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind Ch (eds) UICC TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. Wiley-Liss, New York, NY, in press

- 9.Costa J, Wesley RA, Glatstein E, Rosenberg SA. The grading of soft tissue sarcomas: Results of a clinico pathologic correlation in a series of 163 cases. Cancer. 1984;53(3):530–541. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<530::AID-CNCR2820530327>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks JS. Immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors. Monogr Pathol. 1996;38:65–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folpe AL, & Cooper K (2007) Best Practices in diagnostic immunohistochemistry pleomorphic cutaneous spindle cell tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 131 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Heim-Hall J, Yohe SL. Application of immunohistochemistry to soft tissue neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:476–489. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-476-AOITST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher C. Soft tissue sarcomas with non-EWS translocations:molecular genetic features and pathologic and clinical correlations. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:153–166. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0776-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimura Y, Ohno T, Siddique H, et al. The EWS-ATF-1 gene involved in malignant melanoma of soft parts with t(12;22) chromosome translocation, encodes a constitutive transcriptional activator. Oncogene. 1996;12(1):159–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladanyi M (1995) The emerging molecular genetics of sarcoma translocations. Diagn Mol Pathol 4:162–173 Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y et al (1998) Gain-of-function mutations in c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 279:577–580 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Dei Tos AP. Lipomatous tumours. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2001;7:8–16. doi: 10.1054/cdip.2000.0056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bovée JVMG, Hogendoorn PCW. Molecular pathology of sarcomas: concepts and clinical implications. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plougastel B, Zucman J, Peter M, et al. Genomic structure of the EWS gene and its relationship to EWSR1, a site of tumor-associated chromosome translocation. Genomics. 1993;18:609–615. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romeo S, Angelo P, Tos D. Soft tissue tumors associated with EWSR1 translocation. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:219–234. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, Shmookler BM, Fetsch JF. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934–942. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Argani P, Antonescu CR, Illei PB, et al. Primary renal neoplasms with the ASPL-TFE3 gene fusion of alveolar soft part sarcoma: a distinctive tumor entity previously included among renal cell carcinomas of children and adolescents. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:179–192. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61684-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liegl-Atzwanger B, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CDM. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:111–127. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0891-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park MS, Ravi V, Araujo DM. Inhibiting the VEGF-VEGFR pathway in angiosarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and hemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumor. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:351–355. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833aaad4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]