Abstract

The majority of gastric cancer patients present with advanced, incurable disease and only a minority have localised disease that is suitable for radical treatment. A benefit has generally been demonstrated from adding chemotherapy to surgery for early disease though there are marked differences in how this is done globally. Whilst a perioperative approach, with chemotherapy given before and after gastric surgery is commonly used in the Europe and Australia most patients with operable gastric cancer in North America are treated with surgery and postoperative chemoradiation. In contrast, in East Asia, adjuvant fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy alone is used following D2 gastric resection surgery. However, despite the multimodality treatments, outcomes remain suboptimal as the majority of those treated for localised disease eventually relapse with incurable loco-regional or distant metastases. At the current time, an unmet need exists to further understand the biology of this aggressive disease and develop more efficacious therapies that can improve outcomes from this aggressive disease.

Keywords: Operable gastric cancer, Chemotherapy

Introduction

Despite advances in cancer management, gastric cancer continues to remain a challenging disease to treat. Almost one million new cases and over 738,000 deaths occur from gastric cancer every year, making it the fourth most common malignancy and second most common cause of cancer related death in the world [1]. A marked geographical variation exists, with more than 70% of cases occurring in developing countries and majority being in Eastern Asia [1]. In the Western world gastric cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, in contrast to Japan where patients are more commonly diagnosed at an early stage probably due to an established gastric cancer screening program [2]. Radical surgery is the only modality that can lead to potential cure for localised disease however most patients will relapse post curative resection with loco-regional or metastatic disease leading to poor overall survival [3, 4]. Various multimodality approaches using chemotherapy, radiation or a combination of both have been evaluated in the last few decades in an attempt to improve outcomes post surgery. We here reviewed the most relevant literature regarding the use of chemotherapy in operable gastric cancer, and discuss future strategies to potentially improve outcome.

Staging Investigations and Treatment Planning

All patients with gastric cancer should have a physical examination, liver function tests and renal function tests. A contrast CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis should be done to stage the disease and laparoscopy must be done for all patients with disease greater than T1N0 to rule out occult diaphragmatic disease. Endoscopic ultrasound and PET scan are usually recommended for GOJ carcinomas to further define the T and N stage for assessing tumour operability.

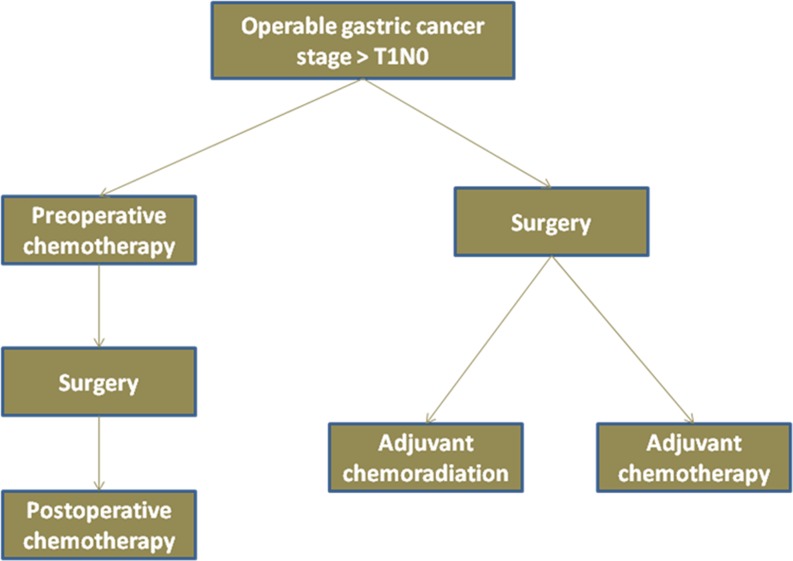

Given the multiple therapeutic strategies and resulting complexities in the management, patients with early gastric cancer are best served by using a multidisciplinary team approach, which should comprise of surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists, gastroenterologists, radiologists and pathologists. Whilst there are no data to support one approach over the other, practice at any particular centre is dictated by local expertise and experience of the treating team. Figure 1 displays the common strategies that are currently used across the world for the management of operable gastric cancer patients.

Fig. 1.

Strategies for integration of systematic therapy in operable gastric cancer

Surgery for Operable Disease

Surgery is an integral part of the definitive management of the patients with early gastric cancer and the extent of surgery is determined by the preoperative stage of the tumour. Whilst endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) may be used to treat very early disease (cancer limited to mucosa, which is ≤2 cm, histologically well differentiated with no evidence of ulceration) [5], most other patients will require a gastrectomy with lymph node dissection. As the incidence of lymph node involvement increases to more than 20% in the tumours involving submucosa and beyond (disease T1N0), these patients should be managed with a multimodality treatment approach as they are at high risk of developing relapse from occult micro-metastatic disease.

There is general agreement regarding the extent of surgery for the primary tumour (proximal, distal, subtotal or total gastrectomy) however the extent of lymphadenectomy (D1: removal of perigastric lymph nodes versus D2: removal of perigastric lymph nodes plus those along the celiac axis and left gastric, common hepatic and splenic arteries) continues to be a matter of great debate. D2 lymphadenectomy is frequently used in East Asia particularly in Japan however data from two large randomised trials conducted in western populations do not support its use over D1 dissection [6, 7]. Recently, the Dutch trial demonstrated a significantly lower locoregional recurrence and gastric cancer related death at 15 years from D2 resection, however in keeping with the initial results, no significant improvement in overall survival (28% versus 22%, p = 0.34) was demonstrated [8]. In spite of these data, extended lymphadenectomy (removal of at least 15 lymph nodes) with spleen preservation is commonly practiced in Western countries as it allows a more precise staging of the tumour and post operative treatment planning.

Adjuvant Treatment in Gastric Cancer

Despite radical surgery, most patients with early gastric cancer develop loco-regional or distant metastatic disease due to presence of occult disease at these sites at the time of initial presentation. Whilst the surgery is aimed at removing all macroscopic sites of disease it has no effect on the micro-metastatic disease that is already established. Both adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy seek to eradicate this micro-metastatic disease in the hope of improved outcomes. A survival benefit has been demonstrated from the addition of chemoradiation or chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting however no benefit has been proven from the usage of adjuvant radiotherapy alone [4, 9, 10].

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Multiple randomized studies, mostly conducted in East Asia have evaluated the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer over the last three decades however, most of them were underpowered to show a benefit and often used what would now be considered relatively less efficacious regimens [11–14]. Whilst it was generally felt until the late 1990s that adjuvant chemotherapy did not confer any benefit in operable gastric cancer [15]; a modest overall survival benefit has since been demonstrated on subsequent meta-analyses in this setting [16–20]. These analyses have mostly been based on the data from the trials conducted in the Far East and only two small randomized trials conducted in the Western populations have so far demonstrated a benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy [21, 22]. Recently, a large individual patient-level meta-analysis (n = 3838) containing data from 17 randomized studies has demonstrated a modest 6% absolute improvement in overall survival from postoperative adjuvant 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy in comparison to surgery alone (55.3% versus 49.6%; HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.76 – 0.90; P < 0.001). In contrast to previous meta-analyses that failed to demonstrate a benefit in Western patients from adjuvant chemotherapy, no significant heterogeneity across randomized studies or for the choice of chemotherapy regimen were reported in this meta-analysis, thereby suggesting a benefit in all patients [23].

The two largest and the most well-known randomised trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer are from East Asia, the ACTS-GC [10] and the CLASSIC [24] study, both of which were conducted to evaluate the role of chemotherapy after D-2 resection surgery (Table 1). The ACTS-GC study randomised 1059 Japanese patients with stage II or III D-2 resected gastric cancer to observation, or 1 year’s treatment with adjuvant S-1 chemotherapy [10]. S-1 is an orally active drug containing tegafur (5-fluorouracil prodrug), gimeracil (an inhibitor of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, which degrades fluorouracil) and oteracil (inhibits phosphorylation of fluorouracil in the GI tract) in a molar ratio of 1:0.4:1. At 3- years, a significant 10% improvement in overall survival was demonstrated from S-1 in comparison to surgery alone (80.1% versus 70.1%; p = 0.002), and updated results demonstrate an ongoing benefit at 5 years, with nearly 11% improvement in overall survival in comparison to the surgery alone arm (5 year overall survival 72.6% versus 61.4%; HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.81) [25]. More recently, results from the phase III Korean CLASSIC study have been reported [24]. In this trial, 1035 patients with stage II-IIIb gastric cancer were randomised after D2 resection surgery to adjuvant CAPOX (capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 bid, d1–14, q3w and oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2, d1, q3w x 8 cycles) or observation alone. The independent data monitoring committee recommended reporting of results following a significant pre-planned interim analysis that demonstrated significantly improved 3-year DFS with adjuvant CAPOX in comparison to surgery alone (74% versus 60%; HR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.44–0.72; p < 0.0001). There was also a non-significant trend towards improved overall survival (HR 0.74; 95% CI, 0.53–1.03; p = 0.0775), though the data are not yet mature for the analysis of overall survival. Based on these data, it is now clear that even after ‘optimal’ (D-2) gastric resection surgery, there is a benefit to be gained from targeting the micro-metastatic disease by using adjuvant chemotherapy. However in spite of these data and that from previous meta-analyses which support using adjuvant chemotherapy, it is seldom practiced outside East Asia due to a general perception about a lack of benefit from it in Western patients and also due to the availability of other proven strategies such as perioperative chemotherapy or adjuvant chemoradiation.

Table 1.

Practice changing clinical trials in operable gastric cancer

| Trial Name | Intervention (no of patients) | 5-year overall survival | HR (95% confidence intervals), P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intergroup 0116[28] | Surgery(277) | 41% | 1.31 (1.09–1.59) |

| Surgery + Adjuvant 5FU/LV chemoradiation (282) | 50% | p = 0.005 | |

| MAGIC[3] | Perioperative chemotherapy + surgery (253) | 36.3% | 0.75 (0.60–0.93) |

| Surgery (250) | 23.0% | p = 0.009 | |

| FFCD[36] | Perioperative chemotherapy + surgery (113) | 38% | 0.69 (0.50–0.95) |

| Surgery (111) | 24% | p = 0.003 | |

| ACTS-GC[25] | Adjuvant S-1 (529) | 72.6% | HR 0.65 (0.53–0.81) |

| Observation (530) | 61.4% | ||

| CLASSIC[24]* | Adjuvant CAPOX (520)* | 74% | HR 0.56; (0.44–0.72) |

| Observation(515)* | 60% | p < 0.0001 |

* Survival values given for CLASSIC study are for 3-year disease free survival

Adjuvant Chemoradiation

Given the high rate of relapse at the loco-regional site in patients with gastric cancer, adjuvant radiation and in particular adjuvant chemoradiation have also been evaluated in clinical trials. Although no benefit was demonstrated from the use of radiation post radical gastric surgery encouraging effects on local control and survival were seen from chemoradiation in some studies [9, 26, 27]. These data prompted evaluation of adjuvant chemoradiation on a much larger scale in the phase III US Intergroup 0116 study which randomised 556 patients post radical gastric surgery (stage 1B – IV) to observation alone or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy [4]. In the chemoradiation arm, patients received adjuvant treatment with five monthly cycles of chemotherapy with bolus 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin daily for 5 days. Radiation was given concurrently with cycle 2 and 3 with a lower dose of 5-FU. At 5 years of follow up, the chemoradiation arm demonstrated a significant improvement in median overall survival (36 months versus 27 months; p = 0.005) and progression free survival (HR 1.52; 95% CI, 1.23–1.86; p < 0.001) in comparison to the surgery alone arm (Table 1). Recently results with more than 10-year median follow up have confirmed an ongoing benefit from adjuvant chemoradiation, with a significantly improved disease free and overall survival (HR 1.51, p < 0.001; HR = 1.32, p = 0.004; respectively) in the tri-modality treatment arm [28]. Following the results from this trial, adjuvant chemoradiation was widely adopted as a standard therapy for treating patients after curative gastric surgery in North America; however to date there continue to be reservations elsewhere about this approach due to concerns about the quality of the surgery used and the toxicity that was seen with abdominal chemoradiation in this trial. Even though most patients in this study had a high-risk of relapse (more than 2/3 of patients had T3 or T4 tumours and 85% had positive lymph nodes on pathology), only 10% of these patients had D2 dissection and 54% had incomplete (D0) lymph node dissection. It is widely argued that the negative effect of ‘suboptimal’ surgery in leaving behind active lymph node disease was probably counterbalanced by the use of adjuvant chemoradiation, leading to a superior survival in the tri-modality arm although, a post-hoc analysis by the study authors demonstrated no difference in the treatment outcome by the level of surgery performed [29]. Furthermore, it is also felt that in the presence of adequate surgery (D2 dissection), there is little (if any) role for adjuvant chemoradiation. Although, previous retrospective analyses suggested a possible benefit from chemoradiation after gastric surgery, no benefit was seen in the recently reported Korean ARTIST trial [30–32]. In this prospective phase III trial, 458 patients were randomized post D2 gastric resection to either adjuvant cisplatin and capecitabine or cisplatin/capecitabine chemoradiation. After a median follow-up of 53.2 months, there was no significant difference in the 3-year disease-free survival, primary end point of the trial, between the two arms (78.2% versus 74.2%; p = 0.0862) though a significant benefit was demonstrated in a subgroup of patients with positive pathological lymph nodes (77.5% versus 72.3%; p = 0.0365). Nonetheless, at present, despite all the controversies and doubt, adjuvant chemoradiation continues to be widely practised in North America as one of the standard options for treatment of gastric cancer patients post curative surgery.

Despite tri-modality treatment outcomes remain generally suboptimal and hence alternative systemic strategies such as using combination chemotherapy with adjuvant chemoradiation have also been evaluated in recent times. One such strategy was used in the CALGB 80101 trial, which assessed the benefit of adding a triplet chemotherapy regimen (epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-FU [ECF]) to adjuvant 5-FU chemoradiation in patients (n = 546) with curatively resected adenocarcinoma of the stomach or GOJ [33]. However, this trial only used one cycle of full dose ECF regimen before chemo radiation and another two cycles of dose attenuated ECF were given post chemoradiation. Results from this trial were presented at the 2011 ASCO annual meeting where no significant difference in median overall (37 months versus 38 months; HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.80–1.34; p = 0.80) or disease free survival (30 months versus 28 months; HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.79–1.27; p = 0.99) was reported, implying no benefit from the addition of combination ECF chemotherapy to 5-FU chemoradiation. However, given the relatively low dose intensity of the ECF chemotherapy and the small number of cycles of triplet chemotherapy used, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions regarding the role of this strategy at this stage.

Perioperative Chemotherapy

Although adjuvant chemotherapy has demonstrated improved survival from gastric cancer, it is challenging to use it in most patients. Often post major surgery such as total gastrectomy, there can be long delays before patients are fit enough to start adjuvant chemotherapy, thus a number of patients are unable to have any post operative treatment, potentially leaving behind untreated micro-metastatic disease. Therefore, neoadjuvant chemotherapy has also been evaluated in gastric cancer as in general, it is much better tolerated than adjuvant chemotherapy, leading to a greater proportion of patients being able to have systemic treatment [34]. Additionally, the usage of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may lead to downsizing of the tumour which may facilitate a curative resection in a greater proportion of patients. With this in mind, the EORTC 40954 study (n = 144) evaluated the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in early gastric cancer however, the trial was closed early due to poor accrual [35]. An increased rate of R0 resection was seen (81.9% versus 66.7%, p = 0.036) with the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy but this did not translate into a benefit in overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.52–1.35; P = .466). Given the lack of supporting data, at this stage a purely neoadjuvant chemotherapeutic strategy should not be used in early gastric cancer. In contrast, a survival benefit from use of a perioperative (preoperative plus post operative chemotherapy) strategy has been demonstrated in two European randomised trials that are discussed below (Table 1).

The phase III UK Medical Research Adjuvant Gastric Cancer Study (MAGIC) randomised 503 patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, oesophago-gastric junction (OGJ), or lower oesophagus to either perioperative chemotherapy and surgery or surgery alone [3]. All patients were planned to receive three cycles of preoperative ECF (Intravenous epirubicin 50 mg/m2 and cisplatin 60 mg/m2 on day 1, and a continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil 200 mg/m2day for 21 days) chemotherapy and three cycles of the same chemotherapy after surgery. At a median follow up of 4 years, the addition of perioperative chemotherapy demonstrated a significant improvement in progression-free survival (HR 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53–0.81; p < 0.001) and overall survival (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.60–0.93; p = 0.009; five-year survival rate, 36% vs 23%). Importantly, the addition of preoperative chemotherapy did not increase complications from surgery and similar rates of postoperative morbidity and 30-day mortality were seen in both arms. In comparison to the surgery alone arm, a significantly higher proportion of patients treated with chemotherapy had curative resections (as deemed by the surgeon; 79.3% vs 70.3%; p = 0.03) and were also found to have significantly smaller tumours and lower nodal burden at surgery. There was no heterogeneity of treatment effect according to the site of primary tumour (stomach, GOJ or lower oesophagus). Although 91% of patients were able to complete 3 cycles of preoperative treatment, only 50% could complete all postoperative treatment, thereby highlighting the challenges involved in administering chemotherapy after radical gastric surgery.

The benefit from using a perioperative approach for early gastric cancer has also been confirmed by another European study, the phase III French FNCLCC ACCORD 07/FFCD 9703 trial [36]. 224 patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, GOJ or lower oesophagus were randomised to either surgery alone or surgery plus perioperative chemotherapy. In the experimental arm, 2–3 cycles of cisplatin & 5-flurouracil (5-fluorouracil 800 mg/m2/day as continuous intravenous infusion D1-5 and cisplatin 100 mg/m2 as a 1-h infusion, every 28 days) were given preoperatively, and 3–4 cycles of the same regimen postoperatively. Postoperative treatment was given in patients who tolerated pre operative treatment well and had no evidence of progressive disease after preoperative chemotherapy, for a total of 6 cycles. Similar to the results from the MAGIC trial [3], there was a clinically and statistically significant improvement in the five-year disease-free survival (34% versus 21%; HR: 0.69; 95% CI 0.50–0.95; p = 0.021) and overall survival (38% vs 24%; HR: 0.69; 95% CI 0.50–0.95; p = 0.02) for the group treated with perioperative chemotherapy in comparison to the surgery alone thereby, reinforcing the case for systemic therapy in gastric cancer. Although there was increased toxicity in the chemotherapy arm, postoperative morbidity was similar in the two groups. Furthermore, similar to the MAGIC trial [3], only 50% of patients could manage to have postoperative chemotherapy compared to nearly 87% who received at least 2 cycles of preoperative chemotherapy, again highlighting the importance of delivering chemotherapy before surgery in the treatment of early gastric cancer.

Based on the results from the MAGIC [3] and now the FNCLCC [36] study, perioperative chemotherapy is now widely practiced as standard treatment especially across Europe and Australia for treatment of operable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, GOJ or lower oesophagus. Additionally, this regimen is being used as a backbone to evaluate newer drugs in this setting, although capecitabine has largely replaced infusional 5-fluorouracil, due to the ease of administration and extrapolation from non-inferiority data reported in the advanced disease setting [37]. As preoperative chemotherapy leads to a higher rate of curative resections compared to surgery alone, adoption of a perioperative approach may allow treatment of a greater proportion of operable gastric cancer patients with systemic chemotherapy in contrast to using postoperative chemoradiation, where ideally, only patients with curative resection should be selected for adjuvant treatment [3, 4, 36].

Neoadjuvant Strategies

In contrast to stomach cancer where no benefit has been proven from a purely neoadjuvant chemotherapy approach, a benefit has been demonstrated from both neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation in clinical trials of oesophageal cancer [35, 38, 39]. As these trials also included patients with GOJ adenocarcinomas, a neoadjuvant chemotherapy approach may be used to manage these tumours, particularly the type I & type II GOJ adenocarcinomas which are generally treated similar to oesophageal cancers. In North America, most patients with GOJ tumours receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation though a perioperative approach is preferred in Europe, with neoadjuvant chemoradiation being reserved for bulky GOJ tumours with threatened circumferential resection margin. Given the data so far, a purely neoadjuvant approach should only be considered for patients with oesophageal or GOJ carcinomas, and patients with stomach cancer should not be treated routinely with this approach. .

Future Strategies for Management of Gastric Cancer

Although there have been advances in the treatment of early gastric cancer, outcomes still remain poor with the majority of patients eventually dying from disease relapse. An unmet need exists to develop more efficacious therapies and treatment strategies. Currently, several trials are planned or ongoing internationally using conventional approaches, novel therapeutic agents or imaging modalities to improve outcomes from this aggressive disease (Table 2). Amongst conventional approaches, the ongoing phase III CRITICS trial will evaluate the benefit of postoperative chemoradiation after gastric resection. Following 3 cycles of preoperative ECX chemotherapy and radical surgery, patients will be randomised into post operative cisplatin-capecitabine chemoradiation or postoperative ECX combination chemotherapy [40]. Another large randomised controlled study, the SAMIT trial, which recently completed accrual of 1495 early gastric cancer patients in a 2X2 design to adjuvant fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy with UFT or S-1, or sequential paclitaxel and then UFT or S-1, will evaluate the role of taxanes in the adjuvant setting [41].

Table 2.

Selected ongoing phase III trials of systemic therapy in operable gastric cancer

| Trial name (no of patients planned) | Eligible population | Treatment arms |

|---|---|---|

| ST03[50] (950) | Stage Ib-IV resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach or GOJ | Perioperative ECX 3 cycles before and 3 after surgery |

| Perioperative ECX + bevacizumab 3 cycles before and 3 after surgery followed by maintenance bevacizumab for 6 cycles. | ||

| CRITICS[40] (788) | Stage Ib-IV gastric cancer | Perioperative ECX chemotherapy before and after surgery |

| Preoperative ECX chemotherapy then adjuvant CX chemoradiation | ||

| SAMIT[41] (1495) | T3/T4 gastric carcinoma | Adjuvant S-1 for 11 months |

| Adjuvant UFT for 11 months | ||

| Adjuvant paclitaxel for 3 months followed by UFT for 8 months | ||

| Adjuvant paclitaxel for 3 months followed by UFT for 8 months |

It has become increasingly apparent that not all cancers are the same and there is marked inter- and intra-tumour variation and complexity at the molecular level, including in gastric cancer. Multiple intracellular pathways have been identified in various cancers which may allow selective modulation/targeting of the pathway as a strategy to control cancer growth. A notable example is the angiogenesis pathway which has been recognised as an important aspect of tumourigenesis for any cancer type. In patients with gastric cancer, increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) has been shown to confer a poor prognosis and increased tumour aggressiveness [42, 43]. Targeting of the angiogenesis pathway has been shown to be of benefit across many cancer types, including colon cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer [44–47]. Following on from encouraging results that were seen in the early phase studies, [48] the randomised phase III AVAGAST study evaluated the role of bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A in 774 patients with advanced gastric cancer [49]. Although there was no improvement in overall survival, the primary endpoint of the study, a significant improvement was seen in response rate and progression free survival.

In operable gastric cancer, a higher response rate to preoperative chemotherapy may potentially facilitate a greater rate of R0 resection and a longer duration of disease control may translate into improved survival. Currently, the UK MRC ST03 study is evaluating the role of bevacizumab in operable gastro-oesophageal cancer and aims to randomise 950 patients to perioperative ECF chemotherapy +/- bevacizumab [50].

Another example of targeted therapy is the recognition of HER-2 subtype, seen in about 20–25% of patients with advanced gastric cancer [51], though recent data report a much lower rate in East Asia in comparison to the West [52–54]. A significant improvement in response rate, progression-free and overall survival was demonstrated from the addition of trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against HER-2, to cisplatin-5FU chemotherapy in the phase III TOGA study, which pre selected patients with advanced gastric cancer for HER-2 over-expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and FISH test [55]. Given the significant benefit seen in the advanced disease setting, it is likely that a benefit may also be seen from using trastuzumab in early disease. A phase II Spanish trial is currently evaluating the role of role of trastuzumab with perioperative capecitabine and oxaliplatin chemotherapy without epirubicin [56]. Due to the risk of additive cardio-toxicity with anthracyclines, the evaluation of trastuzumab in combination with perioperative ECF chemotherapy is challenging.

Additional therapeutic targets such as c-met amplification/overexpression and FGFR2 amplification have been identified in even smaller subsets of gastric cancer, which may be the driver oncogenic abnormality at the cellular level [57, 58]. Indeed clinical trials with novel agents targeting these pathways are currently underway or planned for evaluating this further in the advanced disease setting [59, 60]. If found efficacious in the advanced disease setting, it is likely that these agents will be evaluated in early gastric cancer. This will hopefully allow oncologists to provide personalised treatment to cancer patients based on individual tumour characteristics. However, this is by no means an easy task as only a small proportion of operable gastric cancer patients will be eligible. Hence conducting a clinical trial that will benefit only a relatively small subgroup of patients will require a huge commitment of resources and significant global coordination between the various trial groups and pharmaceutical companies.

It is imperative that the current clinical trial research must also evolve and keep pace with the development that is currently being seen in the preclinical world of cancer therapeutics. Usually, clinical trials allow collection of high quality prospective clinical data which is essential for interpretation of any subsequent innovative research. All investigators and pharmaceutical companies must now endeavour to also collect tissue and blood in a standardised way as part of ongoing clinical trials for translational analysis which as we have seen frequently in recent times, is of immense importance to analyse benefit from any targeted agent. Given the selectivity of targeted agents, it is likely that not all patient groups will benefit and perhaps future translational research into potential biomarkers will help selecting patients for therapy leading to a more personalized approach rather than the current ‘one size fits all’ approach that has generally been used so far in the management of gastric cancer.

In parallel with the developments in targeted therapy, changes have also occurred in various imaging modalities which may now allow us to better define the tumour or even predict for patients who may respond to therapy. Indeed, in recent years, response evaluation on PET scan, as measured by a decrease in the tumour glucose standard uptake value (SUV), has been used to predict response to chemotherapy in many tumour types including tumours of the GOJ [61]. Following treatment with preoperative chemotherapy, early metabolic response in the tumour on the PET scan has been shown to correlate well with the clinical and pathological response and survival [62], and perhaps this strategy in future could allow us to identify patients who fail to respond to preoperative treatment, thereby providing an opportunity to use a salvage regimen.

Summary

Despite recent advances, outcomes remain generally suboptimal for early gastric cancer patients. Whilst it is clear that a benefit is seen from targeting the occult micro-metastatic disease with chemotherapy, there is marked variation in how this is done across the world. In recent years, an increased understanding of the disease biology and cancer in general has occurred, leading to many new therapeutic targets that are currently being tested in clinical trials. Ongoing research will hopefully identify new therapies that are efficacious and biomarkers that are predictive, bringing us one step closer to the goal of personalised treatment for gastric cancer patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge National Health Service funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre.

Conflicts of Interests

Dr Vikram K Jain has no conflicts of interest.

Dr Sheela Rao has consultant/advisory role for Roche, Merck Sereno, Pfizer, Celgene and Sanofi.

Prof Cunningham has received research funding from Roche and Amgen, and has participated in uncompensated advisory boards for Roche and Amgen.

Contributor Information

Vikram K. Jain, Phone: +44-208-6426011, Email: vikramjain02@gmail.com

David Cunningham, Phone: +44-208-6113750, Email: David.cunningham@rmh.nhs.uk.

Sheela Rao, Phone: +44-208-6613587, FAX: +44-208-6613890, Email: sheela.rao@rmh.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN 2008 (2010) Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. [http://globocan.iarc.fr]

- 2.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(957):419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(10):725–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s101200200000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Bonenkamp JJ, Klein Kranenbarg E, Songun I, Welvaart K, van Krieken JH, Meijer S, Plukker JT, et al. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2069–2077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, Sydes M, Fayers P. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(9–10):1522–1530. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(5):439–449. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallissey MT, Dunn JA, Ward LC, Allum WH. The second British Stomach Cancer Group trial of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy in resectable gastric cancer: five-year follow-up. Lancet. 1994;343(8909):1309–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, Furukawa H, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y, Imamura H, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1810–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima T, Nashimoto A, Kitamura M, Kito T, Iwanaga T, Okabayashi K, Goto M. Adjuvant mitomycin and fluorouracil followed by oral uracil plus tegafur in serosa-negative gastric cancer: a randomised trial. Gastric Cancer Surgical Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354(9175):273–277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lise M, Nitti D, Marchet A, Sahmoud T, Buyse M, Duez N, Fiorentino M, Dos Santos JG, Labianca R, Rougier P, et al. Final results of a phase III clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with the modified fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin regimen in resectable gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(11):2757–2763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.11.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coombes RC, Schein PS, Chilvers CE, Wils J, Beretta G, Bliss JM, Rutten A, Amadori D, Cortes-Funes H, Villar-Grimalt A, et al. A randomized trial comparing adjuvant fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin with no treatment in operable gastric cancer. International Collaborative Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(8):1362–1369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.8.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krook JE, O'Connell MJ, Wieand HS, Beart RW, Jr, Leigh JE, Kugler JW, Foley JF, Pfeifle DM. Twito DI: a prospective, randomized evaluation of intensive-course 5-fluorouracil plus doxorubicin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for resected gastric cancer. Cancer. 1991;67(10):2454–2458. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910515)67:10<2454::AID-CNCR2820671010>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermans J, Bonenkamp JJ, Boon MC, Bunt AM, Ohyama S, Sasako M, Van de Velde CJ. Adjuvant therapy after curative resection for gastric cancer: meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(8):1441–1447. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earle CC, Maroun JA. Adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection for gastric cancer in non-Asian patients: revisiting a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35(7):1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mari E, Floriani I, Tinazzi A, Buda A, Belfiglio M, Valentini M, Cascinu S, Barni S, Labianca R, Torri V. Ann Oncol. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of published randomised trials. A study of the GISCAD (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dei Carcinomi dell'Apparato Digerente) 2000;11(7):837–843. doi: 10.1023/a:1008377101672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panzini I, Gianni L, Fattori PP, Tassinari D, Imola M, Fabbri P, Arcangeli V, Drudi G, Canuti D, Fochessati F, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and a comparison with previous meta-analyses. Tumori. 2002;88(1):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janunger KG, Hafstrom L, Glimelius B. Chemotherapy in gastric cancer: a review and updated meta-analysis. Eur J Surg. 2002;168(11):597–608. doi: 10.1080/11024150201680005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun P, Xiang JB, Chen ZY. Meta-analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy after radical surgery for advanced gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96(1):26–33. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirera L, Balil A, Batiste-Alentorn E, Tusquets I, Cardona T, Arcusa A, Jolis L, Saigi E, Guasch I, Badia A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of adjuvant mitomycin plus tegafur in patients with resected stage III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3810–3815. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neri B, Cini G, Andreoli F, Boffi B, Francesconi D, Mazzanti R, Medi F, Mercatelli A, Romano S, Siliani L, et al. Randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy versus control after curative resection for gastric cancer: 5-year follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(7):878–880. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, Pignon JP, Rougier P, Sakamoto J, Sargent D, Sasako M, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1729–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, Lee KW, Kim YH, Noh SI, Cho JY et al (2012) Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sasako M, Kinoshita T, Furukawa H, Yamaguchi T, Nashimoto A, Fujii M, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y. Five-year results of the randomized phase III trial comparing S-1 monotherapy versus surgery alone for stage II/III gastric cancer patients after curative D2 gastrectomy (ACTS-GC study) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Supplement 8):viii225–viii249. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moertel CG, Childs DS, O'Fallon JR, Holbrook MA, Schutt AJ, Reitemeier RJ. Combined 5-fluorouracil and radiation therapy as a surgical adjuvant for poor prognosis gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(11):1249–1254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A comparison of combination chemotherapy and combined modality therapy for locally advanced gastric carcinoma. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer 1982, 49(9):1771–1777 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Macdonald JS, Benedetti J, Smalley S, Haller D, Hundahl S, Jessup J, Ajani J, Gunderson L, Goldman B, Martenson J. Chemoradiation of resected gastric cancer: a 10-year follow-up of the phase III trial INT0116 (SWOG 9008) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macdonald JS, Smalley S, Benedetti J, Estes N, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup M, Martenson JA (2004) Postoperative combined radiation and chemotherapy improves disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in resected adenocarcinoma of the stomach and gastroesophageal junction: Update of the results of Intergroup Study INT-0116 (SWOG 9008). In: 2004 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium [Abstract 6]: 2004

- 30.Kim S, Lim DH, Lee J, Kang WK, MacDonald JS, Park CH, Park SH, Lee SH, Kim K, Park JO, et al. An observational study suggesting clinical benefit for adjuvant postoperative chemoradiation in a population of over 500 cases after gastric resection with D2 nodal dissection for adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(5):1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coburn NG, Govindarajan A, Law CH, Guller U, Kiss A, Ringash J, Swallow CJ, Baxter NN. Stage-specific effect of adjuvant therapy following gastric cancer resection: a population-based analysis of 4,041 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(2):500–507. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J, Lim do H, Kim S, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Choi MG, Sohn TS, Noh JH, et al. Phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus cisplatin versus capecitabine plus cisplatin with concurrent capecitabine radiotherapy in completely resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: the ARTIST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(3):268–273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuchs CS, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Mamon HJ, Swanson R, Haller DG, Dragovich T, Alberts SR, Bjarnason GA et al (2011) Postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation for gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma using epirubicin, cisplatin, and infusional (CI) 5-FU (ECF) before and after CI 5-FU and radiotherapy (CRT) compared with bolus 5-FU/LV before and after CRT: Intergroup trial CALGB 80101. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr 4003)

- 34.Biffi R, Fazio N, Luca F, Chiappa A, Andreoni B, Zampino MG, Roth A, Schuller JC, Fiori G, Orsi F et al. Surgical outcome after docetaxel-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally-advanced gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol, 16(7):868–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Schuhmacher C, Gretschel S, Lordick F, Reichardt P, Hohenberger W, Eisenberger CF, Haag C, Mauer ME, Hasan B, Welch J, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for locally advanced cancer of the stomach and cardia: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized trial 40954. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5210–5218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, Conroy T, Bouche O, Lebreton G, Ducourtieux M, Bedenne L, Fabre JM, Saint-Aubert B, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1715–1721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, Middleton G, Daniel F, Oates J, Norman AR. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):36–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allum WH, Stenning SP, Bancewicz J, Clark PI, Langley RE. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(30):5062–5067. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, Kelly A, Keeling N, Hennessy TP. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dikken JL, van Sandick JW, Maurits Swellengrebel HA, Lind PA, Putter H, Jansen EP, Boot H, van Grieken NC, van de Velde CJ, Verheij M, et al. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and chemotherapy or by surgery and chemoradiotherapy for patients with resectable gastric cancer (CRITICS) BMC Cancer. 2011;11:329. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuburaya A, Yoshida K, Kobayashi M, Yoshino S, Miyashita Y, Morita S, Oba K, Buyse ME, Macdonald JS, Sakamoto J (2011) SAMIT: Preliminary safety data from a 2x2 factorial randomized phase III trial to investigate weekly paclitaxel (PTX) followed by oral fluoropyrimidines (FPs) versus FPs alone as adjuvant chemotherapy in patients (pts) with gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr 4017)

- 42.Kim SE, Shim KN, Jung SA, Yoo K, Lee JH. The clinicopathological significance of tissue levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor in gastric cancer. Gut Liver. 2009;3(2):88–94. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lieto E, Ferraraccio F, Orditura M, Castellano P, Mura AL, Pinto M, Zamboli A, De Vita F, Galizia G. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is an independent prognostic indicator of worse outcome in gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(1):69–79. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, Dickler M, Cobleigh M, Perez EA, Shenkier T, Cella D, Davidson NE. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(26):2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, Leighl N, Mezger J, Archer V, Moore N, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, Mannel RS, Homesley HD, Fowler J, Greer BE, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah MA, Ramanathan RK, Ilson DH, Levnor A, D'Adamo D, O'Reilly E, Tse A, Trocola R, Schwartz L, Capanu M, et al. Multicenter phase II study of irinotecan, cisplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5201–5206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kang Y, Ohtsu A, Van Cutsem E, Rha SY, Sawaki A, Park S, Lim H, Wu J, Langer B, Shah MA. AVAGAST: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of first-line capecitabine and cisplatin plus bevacizumab or placebo in patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:18s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Combination Chemotherapy With or Without Bevacizumab in Treating Patients With Previously Untreated Stomach Cancer or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer That Can Be Removed by Surgery [http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00450203?term=st03&rank=1]

- 51.Bang Y, Chung H, Xu J, Lordick F, Sawaki A, Lipatov O, Al-Sakaff N, See C, Rueschoff J, Cutsem EV. Pathological features of advanced gastric cancer (GC): Relationship to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positivity in the global screening programme of the ToGA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terashima M, Ochiai A, Kitada K, Ichikawa W, Kurahashi I, Sakuramoto S, Fukagawa T, Sano T, Imamura H, Sasako (2011) Impact of human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and ERBB2 (HER2) expressions on survival in patients with stage II/III gastric cancer, enrolled in the ACTS-GC study. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr 4013)

- 53.Shah MA, Janjigian YY, Pauligk C, Werner D, Kelsen DP, Jaeger E, Altmannsberger H, Robinson E, Tang LH, Barbashina VV et al (2011) Prognostic significance of human epidermal growth factor-2 (HER2) in advanced gastric cancer: A U.S. and European international collaborative analysis. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr 4014)

- 54.Park Y, Ryu M, Park H, Kim H, Ryoo B, Yook J, Kim B, Jang S, Kang Y (2011) HER2 status as an independent prognostic marker in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after curative gastrectomy. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr 4084)

- 55.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.An Open-label, Multi-center Study to Evaluate the Disease Free Survival Rate of a Perioperative Combination of Capecitabine (Xeloda), Trastuzumab (Herceptin) and Oxaliplatin (XELOX- Trastuzumab) in Patients With Resectable Gastric or Gasro-esophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma [http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01130337?term=trastuzumab+AND+gastric+cancer&rank=8]

- 57.Galluccio N, Ruzzo A, Canestrari E, Lorenzini P, d'Emidio S, Sisti V, Catalano V, Andreoni F, Zingaretti C, De Nictolis M et al (2011) C-MET gene copy number variation (CNV) analysis by quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay in Caucasian patients with gastric cancer (GC). J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl; abstr 4038)

- 58.Kunii K, Davis L, Gorenstein J, Hatch H, Yashiro M, Di Bacco A, Elbi C, Lutterbach B. FGFR2-amplified gastric cancer cell lines require FGFR2 and Erbb3 signaling for growth and survival. Cancer Res. 2008;68(7):2340–2348. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.AMG 102 Plus ECX for Unresectable Locally Advanced or Metastatic Gastric or Esophagogastric Junction Cancer [http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00719550?term=AMG+AND+gastric+cancer&rank=1]

- 60.Safety and Efficacy of AZD4547 Versus Paclitaxel in Advanced Gastric or Gastro-oesophageal Junction Cancer Patients (SHINE) [http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01457846?term=AZD4547+AND+gastric+cancer&rank=1]

- 61.Lordick F, Ott K, Krause BJ, Weber WA, Becker K, Stein HJ, Lorenzen S, Schuster T, Wieder H, Herrmann K, et al. PET to assess early metabolic response and to guide treatment of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: the MUNICON phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(9):797–805. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lordick F, Meyer Zum Bueschenfelde C, Herrmann K, Geinitz H, Schuster T, Friess H, Molls M, Schwaiger M, Peschel C, B. K (2011) PET-guided treatment in locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG): The MUNICON-II study. J Clin Oncol 29 (suppl 4; abstr 3)