Abstract

Context:

Bullous pemphigoid (BP), the most common autoimmune blistering disease, is mediated by autoantibodies. BP primarily affects the elderly and is characterized by the development of urticarial plaques surmounted by subepidermal blisters, and the deposition of immunoglobulins and complement at the basement membrane zone (BMZ) of the skin. BP is immunologically characterized by the development of autoantibodies targeting two structural proteins of the hemidesmosomes, BP180 (collagen XVII) and BP230 (BPAG1).

Case Report:

A 63 -year-old Caucasian female patient was evaluated for a 4 day history of several itching, erythematous blisters on her extremities. Biopsies for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) examination, as well as Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), immunohistochemistry (IHC) and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analysis were performed.

Results:

H&E demonstrated a subepidermal blister, with partial re-epithelialization of the blister floor. Within the blister lumen, numerous neutrophils were present, with occasional eosinophils and lymphocytes also noted. Within the dermis, a mild, superficial, perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and occasional eosinophils was identified, with mild perivascular leukocytoclastic debris. The PAS stain was positive at the BMZ, and around selected blood vessels, nerves and sweat glands. DIF revealed linear deposits of IgG and Complement/C3 and fibrinogen at the BMZ, and around selected dermal nerves, blood vessels and sweat glands. Strong granular deposits of IgE were also observed, colocalizing with monoclonal antibodies to Collagen IV (CIV). By IHC, positive CD45 staining of lymphocytes was seen surrounding selected dermal blood vessels, eccrine sweat glands, and nerves.

Conclusion:

The patient displayed IgG, IgE, and fibrinogen autoantibodies against the BMZ, as well as around some dermal nerves and sweat glands; their binding in the skin could trigger complement activation. In addition, the role of the dermal CD45 positive lymphocytes warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Bullous pemphigoid, IgE, nerves and sweat glands, autoantibodies

Introduction

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering disease primarily affecting elderly patients, and characterized by the development of urticarial plaques surmounted by subepidermal blisters and the deposition of both immunoglobulins and complement at the basement membrane zone (BMZ) of the skin. Immunologically, it is characterized by the development of autoantibodies targeting two important proteins of the hemidesmosomes, BP180 (collagen XVII) and BP230[1]. It is known that BP230 is an intracellular protein of the hemidesmosomal plaque, while BP180 is a transmembrane protein containing a collagenous extracellular domain. Significant experimental evidence indicates that BP180 is the primary target of the pathogenic autoantibodies. Autoantibodies are of both the IgG and IgE classes; their binding in the skin triggers complement activation, mast cell degranulation and additional migration of eosinophils, mast cells, and neutrophils[1–4].Discharge of proteases from these inflammatory cells may result in cleavage of the BMZ and subsequent blister formation. However, the initial triggers of BP autoantibody production remain obscure.

Case Report

A 63 year old female patient was referred with a four day history of several, severely pruritic, erythematous blisters and crusts on her extremities (arms and thighs) (Fig. 1). Skin biopsies for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E), as well as for periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed . In addition, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) with 0.1 M sodium chloride salt split skin were performed. In brief, DIF was performed utilizing skin cryosections, incubated with multiple fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies. The secondary antibodies were of rabbit origin, and included: a) anti-human IgG (γ chain), b) anti-human IgA (α chains), c) anti-human IgM (μ-chain), d) anti-human fibrinogen, and e) anti-human albumin (all used at 1:20 to 1:40 dilutions and obtained from Dako (Carpinteria, California, USA). We also utilized secondary antibodies of goat origin, including: a) anti-human IgE antiserum (Vector Laboratories, Bridgeport, New Jersey, USA) and b) anti-human C1q (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama, USA). Finally, monoclonal anti-mouse collagen IV (CIV) from Invitrogen(Carlsbad, California, USA) with a goat anti-mouse Texas red conjugated secondary antibody was utilized to highlight the basement membrane zone (BMZ). The slides were then counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dapi) (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) washed, coverslipped, and dried overnight at 4°C. IHC staining using anti human CD45 was performed using a Dako automatized dual endogenous flex system, following Dako technical instructions.

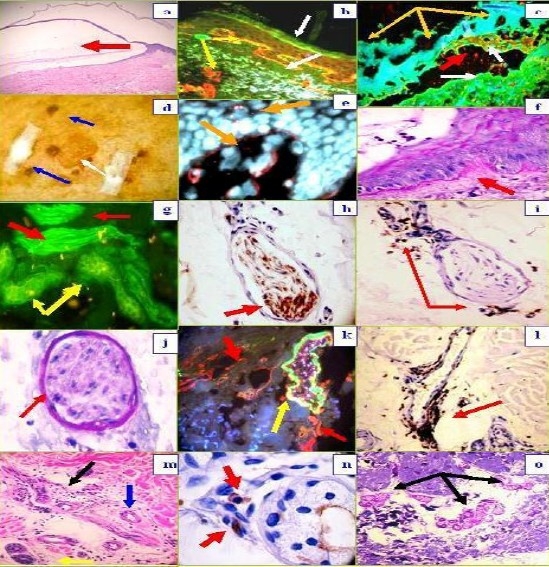

Fig. 1a.

H & E staining (100X) demonstrating the subepidermal blister (red arrow). 1b, DIF, positive staining with FITC conjugated anti-human IgE at the BMZ in a linear pattern (green staining, lower white arrow), colocalizing with the collagen IV(CIV) antibody (red staining, top yellow arrow). Please notice that CIV also stains the upper dermal blood vessel areas (lower yellow arrow). The epidermal corneal layer also shows some IgE reactivity (upper white arrow). 1c. DIF, showing destruction of epidermal keratinocytes, characterized by amorphous staining of cell nuclei with Dapi (blue staining, yellow arrows). The red arrow shows defragmented pieces of CIV in the blister lumen (red particles); the white arrows show positive staining with FITC conjugated antihuman fibrinogen, on both sides of the blister (epidermal and dermal). 1d , Shows a clinical blister (white arrow) and some adjacent crusts (blue arrows). 1e, DIF. Note the keratinocytes nuclei in blue (Dapi), and the mapping of the blister with CIV antibody (red staining, yellow arrows). Please note the delicate, trans-epidermal excretion of tiny fragments of CIV, seen as small red dots among the keratinocytes. 1f. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain, displaying pink positivity at the BMZ (red arrow). 1g. Positive staining of a nerve with FITC conjugated anti-human fibrinogen (green staining; red arrows), as well as against eccrine sweat glands (yellow arrows). 1h. The identity of the nerve was confirmed by colocalizing, positive S-100 IHC staining (brown staining, red arrow). 1i, 1l and 1n. In addition, we utilized IHC to confirm a significant lymphocytic infiltrate around dermal neurovascular package and eccrine sweat glands with CD45 (brown staining, red arrows) . 1j. PAS positive, pink staining of a nerve sheath (red arrow). 1k, DIF positive staining of a blood vessel wall with FITC conjugated Complement/C3 (green-yellowish staining, yellow arrow), colocalizing with CIV antibody (red staining, red arrows). 1m. H & E stain, showing lymphocytes infiltrating around dermal nerves (black arrow), eccrine sweat glands (yellow arrow) and an eccrine sweat gland ductus (blue arrow). 1o. PAS positive staining of eccrine sweat gland peripheral membranes (pink staining, black arrows).

In Figure 1, we highlight our most significant H & E, PAS, DIF and IHC results, including localization of the BMZ autoantibodies utilizing the IIF sodium chloride split skin technique[4]. The DIF results in the basement membrane zone of the skin (BMZ) were as follows: IgG, linear, ++; IgE, granular, ++; C3, linear, ++; fibrinogen, linear, ++; Complement/C1q, linear, +/-; albumin, linear, +/-; Fibrinogen, linear, ++, and collagen IV, linear, ++. Within the dermis, we observed IgE, fibrinogen and C3 perineural and sweat gland reactivity (++). Indirect immunofluorescence(IIF) performed on 1M NaCl salt split skin displayed the following results: IgG (+, linear, blister roof); IgA (+, linear, blister roof); IgM (+, linear, blister roof); IgE (+, dermal perivascular and perineural); Complement/C1q(+, linear, blister roof); Complement/C3 (+, linear, blister roof); Albumin(+, linear, blister roof); and Fibrinogen (+, linear, blister roof).

Examination of the H&E tissue sections demonstrated a subepidermal, tense blister, with partial re-epithelialization of the blister floor. No impetiginization of the epidermis was seen. Within the blister lumen, numerous neutrophils were present, with occasional eosinophils and lymphocytes also noted. Dermal papillary festoons were not observed (Fig. 1). Within the dermis, a mild, superficial, perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and occasional eosinophils was identified. Neutrophils were rare. Mild perivascular leukocytoclastic debris was present, but no frank vasculitis was appreciated. A PAS special stain displayed positivity at the basement membrane zone (BMZ), as well as around some dermal blood vessels, nerves and eccrine sweat glands (Fig. 1). The PAS special stain revealed no fungal organisms.

Discussion

Bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) may have indistinguishable clinical, histologic, and routine immunofluorescence features. Thus, these two diseases can be reliably distinguished 1) in seropositive cases by indirect immunoflrouescence (IIF) testing on salt lamina lucida split skin, 2) in research studies by direct immunoelectron microscopy and 3) in patients with circulating autoantibodies, by immunoblotting (IB) Western studies[4]. The use of these methods is limited by their availability and expense, and the requirement for circulating autoantibodies. In our case, following initial direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen, additional salt split skin studies utilizing 1.0 mol/L sodium chloride were performed. In EBA, the IgG linear BMZ deposits classically appear on the dermal side of a split specimen; in BP, predominantly or exclusively in the epidermal side. In our case, the salt split skin pattern favored the diagnosis of BP, with the additional features of IgE and fibrinogen also present on both sides of the NaCl induced blister.

Other differential diagnoses we considered included bullous impetigo, and a bullous arthropod bite reaction. In general, patient encounters with biting or stinging arthropods elicit localized reactions including pruritic macules, urticarial wheals and papular reactions[5,6]. Less frequently, localized bullous or hemorrhagic or disseminated papular reactions may be seen, particularly in children and immunologically naive adults[5,6]. With the exclusion of bee and wasp venom allergies, immediate-type allergic reactions to arthropod stings and bites are uncommon[5,6]. Thus, we considered a bullous arthropod bite reaction in our differential diagnosis, which could produce late-phase reactions including the development of sustained edema, vesicles, blisters, and/or intense pruritus[5,6].

Although IgG represents the most commonly documented immunoglobulin subclass in BP patients, several recent reports also highlight the importance of IgE; its binding in the skin triggers complement activation, and further accumulation of inflammatory cells[7–9]. Indeed, a correlation of IgE autoantibody with BP180 in a severe form of bullous pemphigoid has been described[8]. The case demonstrated positivity with IgG, IgE, fibrinogen and Complement/C3 against not only the BMZ, but also to dermal nerves, blood vessels and sweat glands.

The best chartacterized BP antigens are associated with hemidesmosomes. The hemidesmosomes are present at the BMZ (dermal/epidermal junction). The desmosomes are multi-protein complexes, promoting stable adhesion of epithelial cells to the underlying extracellular matrix[10]. Interactions between different hemidesmosomal components with each other have been studied; these interactions have been studied utilizing double hybrid and cell transfection assays. The results demonstrated that: BP180 binds not only to BP230, but also to plectin[10]. The interactions between these proteins are facilitated by the Y subdomain within the N-terminal plakin domains of BP230 and plectin, and residues 145-230 of the cytoplasmic domain of BP180. Relative to residues 145-230, different, but overlapping, sequences on BP180 mediate binding to integrin ß4 which, in turn, also associates with BP180 via its third fibronectin type III repeat. Further, sequences in the N-terminal extremity of BP230 mediate its binding to integrin ß4, which requires the C-terminal end of the connecting segment (up to the fourth fibronectin repeat of the integrin ß4 subunit)[10]. Based on this knowledge, we speculate that, given our patient's immunofluorescence positivity against the dermal sweat glands, possible epitope spreading between the BP180 and BP230 antigens could elicit reactivity to integrins and/or plectins expressed not only in multiple areas of the BMZ, but also in the dermal nerves, sweat glands and/or microvasculature[11]. In addition, serum from a patient with bullous pemphigoid was recently associated with neurological diseases, recognizing BP antigen in the skin and in the brain[12]. Eccrine syringofibroadenomatous hyperplasia has also been documented in some patients with BP[13,14].

We were able to demonstrate a direct correlation of our DIF and IIF/salt split skin positivity with positive PAS staining. Relative to patients who live in areas where DIF and IIF are not available, the PAS stain often shows a high correlation with the positivity of immunoglobulins and complement in autoimmune diseases, as shown in our case[15–17]. Specifically, PAS is a staining method often used to detect glycogen in tissues. The reaction of periodic acid selectively oxidizes glucose residues, creating aldehydes; these then react with the Schiff reagent, yielding a purple-magenta color. Thus, PAS staining is often utilized for staining structures containing a high proportion of carbohydrate macromolecules (i.e., glycogen, glycoproteins, or proteoglycans), typically found in neutrophils, fungal organisms and basal laminae. Positive PAS staining may be found in diverse autoimmune diseases, including vasculitides, autoimmune bullous diseases, autoimmune nephritis and Goodpasture's syndrome[15–17].

Finally, the significance in our case of abundant CD45 positive lymphocytes around the dermal sweat glands, sweat ducts and neurovascular packages remains unknown. Further investigation of our case features of 1) BP IgE/IgG/fibrinogen linear deposits at the BMZ, 2) auto-reactivity to dermal sweat glands and nerves and 3) CD45 positive infiltrating dermal lymphocytes may lead to a better understanding of this disease.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by the funding from Georgia Dermatopathology Associates, Atlanta, GA, USA.

References

- 1.Wong MM, Giudice GJ, Fairley JA. Autoimmunity in bullous pemphigoid. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:411–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woźniak K, Kowalewski C. Alterations of basement membrane zone in autoimmune subepidermal bullous diseases. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;40:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medenica L, Skiljević D. Diagnostic significance of immunofluorescent tests in dermatology. Med Pregl. 2009;62:539–546. doi: 10.2298/mpns0912539m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gammon WR, Kowalewski C, Chorzelski TP, Kumar V, Briggaman RA, Beutner EH. Direct immunofluorescence studies of sodium chloride-separated skin in the differential diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:664–670. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leverkus M, Jochim RC, Schäd S, et al. Bullous allergic hypersensitivity to bed bug bites mediated by IgE against salivary nitrophorin. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:91–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkisian EC, Boiko S. Acute localized bullous eruption in a boy.Bullous reaction to insect bites. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1329–1332. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690230109019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dresow SK, Sitaru C, Recke A, Oostingh GJ, Zillikens D, Gibbs BF. IgE autoantibodies against the intracellular domain of BP180. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwata Y, Komura K, Kodera M, et al. Correlation of IgE autoantibody to BP180 with a severe form of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:41–48. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Messingham KA, Noe MH, Chapman MA, Giudice GJ, Fairley JA. A novel ELISA reveals high frequencies of BP180-specific IgE production in bullous pemphigoid. J Immunol Methods. 2009;346:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koster J, Geerts D, Favre B, Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Analysis of the interactions between BP180, BP230, plectin and the integrin alpha6beta4 important for hemidesmosome assembly. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:387–399. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hertle MD, Adams JC, Watt FM. Integrin expression during human epidermal development in vivo and in vitro. Development. 1991;112:193–206. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Chen J, Wang B, Yao Y, Zuo Y. Sera from patients with bullous pemphigoid (BP) associated with neurological diseases; recognized BP antigen in the skin and brain. Br J Dermatol. 2009;6:1343–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomura K, Kogawa T, Hashimoto I, Katabira Y. Eccrine syringofibroadenomatous hyperplasia in a patient with bullous pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatologica. 1991;182:59–62. doi: 10.1159/000247740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura K, Hashimoto I. Eccrine syringofibroadenomatosis in two patients with bullous pemphigoid. Dermatology. 1997;195:395–398. doi: 10.1159/000245997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherber NS, Wigley FM, Scher RK. Autoimmune disorders: nail signs and therapeutic approaches. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horiguchi Y, Danno K, Ikai K, Imamura S. Colloid body formation in bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol Res. 1985;277:167–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00404311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danilewicz M, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M. The consequences for renal function of the glomerular deposition of PAS positive material in proliferative glomerulopathies.A quantitative study. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1997;143:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]