Abstract

Inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) shows beneficial effects in animal models of polycystic kidney disease (PKD); however, two clinical trials in patients with autosomal dominant PKD failed to demonstrate a short-term benefit in either the early or progressive stages of disease. The stage of disease during treatment and the dose of mTOR inhibitors may account for these differing results. Here, we studied the effects of a conventional low dose and a higher dose of sirolimus (blood levels of 3 ng/ml and 30–60 ng/ml, respectively) on mTOR activity and renal cystic disease in two Pkd1-mutant mouse models at different stages of the disease. When initiated at early but not late stages of disease, high-dose treatment strongly reduced mTOR signaling in renal tissues, inhibited cystogenesis, accelerated cyst regression, and abrogated fibrosis and the infiltration of immune cells. In contrast, low-dose treatment did not significantly reduce renal cystic disease. Levels of p-S6RpSer240/244, which marks mTOR activity, varied between kidneys; severity of the renal cystic phenotype correlated with the level of mTOR activity. Taken together, these data suggest that long-term treatment with conventional doses of sirolimus is insufficient to inhibit mTOR activity in renal cystic tissue. Mechanisms to increase bioavailability or to target mTOR inhibitors more specifically to kidneys, alone or in combination with other compounds, may improve the potential for these therapies in PKD.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is an important cause of renal failure and results from a mutation in the PKD1 or PKD2 gene. The disease is characterized by progressive deterioration of kidney function because of the formation of thousands of epithelium-derived cysts and fibrosis, leading to renal failure beyond mid-life.

The majority of patients (85%) carry a mutation in PKD1. This gene encodes the protein polycystin-1, which forms multi-protein complexes at the cell membrane and functions in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, signal transduction, and mechanosensation.1–5

A plethora of cellular changes have been observed in cystic epithelium-like cells or tissues, including aberrant Ras/Raf/ERK activation, cAMP accumulation, as well as altered activation of G-proteins, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), PI3-kinase, Jak2-STAT1/3, NFAT, TGFβ, and NF-κβ signaling.6–12 Although there are currently no reliable therapies available and clinical management of ADPKD is mainly focused on managing complications, it is anticipated that new therapeutic interventions targeting these key molecular changes in PKD might prove effective. Clinical trials testing the efficacy of mTOR inhibitors were recently evaluated.13–19

mTOR plays a central role in regulating cell growth by integrating signals from growth factors, nutrients, and cellular energy levels. mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase that forms two distinct physical and functional complexes, TOR complex 1 (TORC1) and TOR complex 2 (TORC2).20 TORC1 is particularly sensitive to mTOR inhibitors (e.g., rapamycin, sirolimus) and regulates translation, cell proliferation, and cell growth. Activation of tuberin, a GTPase-activating protein upstream of TORC1, can cause activation of TORC1. Previously, in vitro studies showed that the C-terminal domain of polycystin-1 interacts with tuberin. This led to the hypothesis that defects in polycystin-1 in ADPKD could promote disruption of the tuberin-TORC1 complex, leading to increased mTOR activity.10

Indeed, mTOR inhibitors effectively ameliorate cyst growth and preserve renal function in a variety of animal models for PKD, including a Pkd1-mutant model.10,21–24 Conflicting results have been obtained in the clinical setting. Although a retrospective study has suggested a significant reduction in renal and hepatic cyst volumes in ADPKD patients receiving mTOR inhibitors after kidney transplantation, two subsequent clinical trials have not shown a clear beneficial effect in ADPKD, both in early and more progressive stages.10,17,18 Possible factors confounding the interpretation of these results could be the stage of disease during treatment and the dose of mTOR inhibitors used.

We have generated several unique well controlled mouse models mimicking PKD, from early phase with epithelium-like cell proliferation to late stages with massive fibrosis and inflammation (Happé et al., 2011, unpublished data).11,25,26 These Pkd1 models were used to investigate the effects of low and high doses of sirolimus at different stages of the disease to determine whether a conventional low dose is as effective at reducing cyst formation and fibrosis as a higher dose, whether conventional low-dose sirolimus inhibits mTOR activity in cystic kidneys, and whether sirolimus is equally effective when initiated later in the disease course compared with early administration.

The overall results from our study indicate that sirolimus can indeed slow down different stages of PKD, but that higher than expected doses of the drug are necessary to obtain a therapeutically useful effect.

Results

Low-Dose Levels of Sirolimus Do Not Significantly Improve the Renal Cystic Phenotype, Whereas High-Dose Levels Do

Sirolimus was administered at different time intervals via food at a high dose (100 mg/kg chow) or a conventional low dose (10 mg/kg chow). Details of the experimental set-up are available in Figure 1.

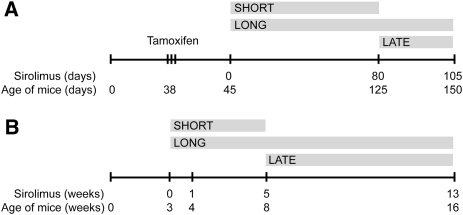

Figure 1.

Study design. (A) iKsp-Pkd1del mice, treated with tamoxifen to disrupt the Pkd1 gene at days 38–40. At day 45, sirolimus was started for the short-term (approximately 80 days) and long-term (105–110 days) treatment groups. At 80 days, the short-term group was sacrificed and treatment was started for the late group. These mice were treated for 25–30 days. (B) For Pkd1nl,nl mice, treatment was started at 3 weeks of age for the short-term (5 weeks) and long-term (13 weeks) treatment groups. At 5 weeks, the short-term group was sacrificed and treatment was started for the late group.

Model 1

Inducible Pkd1-deletion (iKsp-Pkd1del) mice were treated with tamoxifen to inactivate Pkd1 at postnatal days 38–40. Seven days after gene disruption, mice were randomized into controls and the different treatment groups, including a nontreated control group, a group treated with conventional “early start” low-dose sirolimus, a group treated with early start high-dose sirolimus, as well as groups with late start low-dose and high-dose sirolimus. Mice were sacrificed at previously determined time points (Figure 1) or when blood urea (BU) concentrations were >20 mmol/L, usually close to the scheduled dates. Kruskal–Wallis testing indicated that the median dates of sacrifice were not significantly different between the groups (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared test, 5.835; P=0.054). In addition, subgroups of mice were sacrificed after 80 days of treatment (Figure 1A). Mice treated with high- or low-dose sirolimus showed blood levels of 22.93±13.44 ng/ml and 2.47±1.19 ng/ml, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1).

Short Treatment

Eighty days of sirolimus administration in the iKsp-Pkd1del model significantly prevented the increase in two kidney weight/body weight ratios (2KW/BW) (Supplemental Figure 2, A and C) in the high-dose treatment group (mean 1.94%±0.27%; P=0.004) compared with the untreated group (mean 3.48%±0.80%); however, low-dose treatment did not show a significant effect (2.5%±0.58%; P=0.058) (Figure 2A).

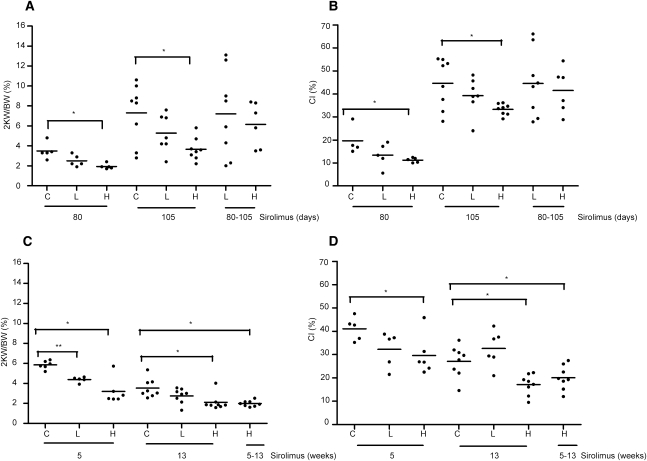

Figure 2.

2KW/BW ratios and cystic indices. (A) The 2KW/BW ratios and (B) the cystic indices are indicated for controls (untreated mutants) and for iKsp-Pkd1del mice receiving chow with high-dose (100 mg/kg chow) or low-dose (10 mg/kg chow) sirolimus. Mice were treated for approximately 80 days, 105 days, or from day 80 to 105/110 (80–105). (C) The 2KW/BW ratios and (D) cystic indices are indicated for Pkd1nl,nl mice receiving chow with high-dose or low-dose sirolimus for 5 weeks, 13 weeks, or from weeks 5 to 13. Data are presented as mean values. A t test for equal variances was used except for the high-dose versus control groups at 13 weeks, in which a t test for unequal variances was used. *P<0.05. **P<0.001 compared with untreated mutants. CI, cystic index; C, controls; L, low-dose sirolimus; H, high-dose sirolimus.

Correspondingly, the renal cystic index was significantly reduced in the high-dose treatment group (11.24%±1.0%) compared with the untreated group (19.69%±6.38%; P=0.075); however, low-dose treatment showed a mild, albeit insignificant, effect on the cystic index (13.44%±5.25%) (Figure 2B).

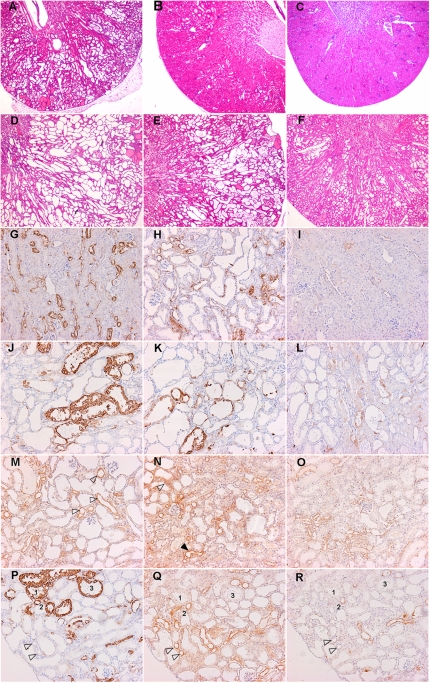

In the high-dose group, in which cyst formation is strongly inhibited, there were hardly any tubular dilations observed and renal tissue architecture appeared almost unaffected, whereas mild dilations and small cortical cysts were detected in the untreated group. Some kidneys in the low-dose group showed mild dilations and small cortical cysts as in untreated mice, whereas other kidneys appeared almost normal as in the high-dose group (Figure 3, A–C).

Figure 3.

Cyst formation and signaling in iKsp-Pkd1del mice. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of renal sections from iKsp-Pkd1del mice at (A through C) 80 days or (D through F) 105 days of treatment. A and D show mice receiving no treatment, B and E show mice receiving low-dose sirolimus, and C and F show mice receiving high-dose sirolimus. Renal sections stained with p-S6RpSer240/244 (G through L, P), p-Aktser473 (M through O, Q), or p-ERK1/2Thr202/Tyr204 (R). (M and N) Arrowheads indicate more or less intense p-Aktser473 signal (black and white arrowhead, respectively). (P through R) Dilated tubules 1–3 are positive for p-S6RpSer240/244 but negative for p-Aktser473 and p-p90 RSKThr359/Ser363 arrowheads indicate tubules negative for p-S6RpSer240/244, positive for p-Aktser473, and with most of the cells negative for p-p90 RSKThr359/Ser363.

Prolonged Treatment

After prolonged treatment (105 days), 2KW/BW ratios were also significantly lower in the high-dose group (3.66%±1.13%; P=0.009) compared with the untreated group (7.3%±2.94%). In the low-dose group, 2KW/BW was lower but not significantly different, due to variability (5.27%±1.88%) (Figure 2A). Again, a similar pattern was observed for the cystic index, which was significantly reduced in the high-dose–treated group (33.3%±2.4%, P=0.022) compared with the untreated group (44.6%±10.88%) and a low-dose showed no significant effect (39.30%±7.88%) (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 2, A–C).

Although mice receiving long-term treatment with high-dose sirolimus displayed dilated tubules (Figure 3F), this phenotype was much milder compared with the untreated group showing large- and medium-sized cysts (Figure 3D), Mice receiving low-dose sirolimus demonstrated a pathology varying from severe to mildly cystic (Figure 3E). Data are not shown for fibrosis in iKsp-Pkd1del mice because the amount of fibrosis in late-stage PKD is relatively low (mice have a fast synchronized proliferative phenotype).

Late Treatment

Although high-dose sirolimus resulted in lower 2KW/BW ratios after short and prolonged treatment, it did not have a significant effect on the 2KW/BW ratio and cystic index when introduced at more advanced stage of disease (after 80 days of control food regime) (Figure 2, A and B). These high-dose–treated and low-dose–treated mice showed a massive cystic phenotype comparable with untreated controls (not shown).

Model 2

In Pkd1nl,nl mice, treatment was started upon weaning at 3 weeks of age (day 21) and mice were fed high- or low-dose sirolimus or control chow for 5 or 13 weeks. The animals were sacrificed at 8 and 16 weeks of age (Figure 1B).

In the late-start treatment groups, mice received control chow for the first 8 weeks and were switched to high-dose sirolimus for the next 8 weeks. Sirolimus blood concentrations measured for mice treated with high dose were 34.93±10.64 in young mice and 76.01±29.67 ng/ml in adult mice. Blood concentrations measured for low-dose–treated mice were 3.13±2.95 and 3.02±0.86 ng/ml, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1B).

Early Treatment

Mice treated with high-dose sirolimus for 5 weeks showed significantly lower 2KW/BW ratios (3.19%±1.28%; P=0.003) compared with untreated mutants (5.86%±0.41%); however, mice treated with low-dose sirolimus also showed significantly lower 2KW/BW ratios (4.39% ±0.27%; P=0.00008) (Figure 2C). 2KW/BW decreased even further after 13 weeks of high-dose treatment (2.11%±0.79%; P=0.005) compared with 5 weeks of treatment, whereas the low-dose group (2.76%±0.75%) showed no significant difference compared with untreated mutants (3.53%±0.94%; P=0.088) (Supplemental Figure 2, B and D).

The cystic index was significantly lower in mice that received high-dose sirolimus after 5 weeks (29.6%±8.5%; P=0.027) and 13 weeks of treatment (17.1%±4.44%; P=0.004) (Figure 2D) compared with untreated groups (41.1%±5.01% and 27.10%±6.76%, respectively). No significant difference was measured for groups that received low-dose sirolimus after 5 weeks (32.2%±7.6%) and 13 weeks of treatment (32.6%±7.7%), respectively.

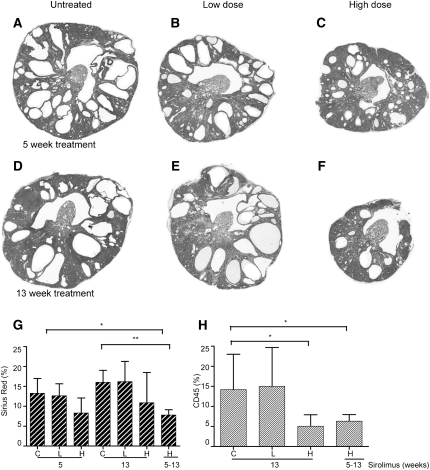

To note, characteristic for this model is a reduction in kidney volume between the age of 4 and 16 weeks as well as an increase in fibrosis and immune cell infiltrations over time (Happé et al., unpublished data). Hence, the untreated mutants also showed a reduced 2KW/BW ratio and cystic index at week 13 compared with weeks 1 and 5 of the experiment (Figure 4, A–F and Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Cyst formation and fibrosis in Pkd1nl,nl mice. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of renal sections from Pkd1nl,nl mice at 5 weeks (A through C) or 13 weeks (D through F) of treatment. A and D show mice receiving no treatment, B and E show mice receiving low-dose sirolimus, and C and F show mice receiving high-dose sirolimus. (G) Fibrotic index indicated by percentage of Sirius red–stained tissue or (H) index for infiltrating immune cells indicated by percentage of CD45 stained tissue for Pkd1nl,nl mice receiving control or low-dose or high-dose sirolimus food for 5 weeks, 13 weeks, or from weeks 5 to 13. *P<0.05. **P<0.001 compared with untreated mutants.

Interstitial fibrosis is a major factor contributing to renal failure in ADPKD. We used Sirius red to identify extracellular matrix (collagen) deposition. In untreated and low-dose–treated Pkd1nl,nl mice, fibrosis and inflammation strongly increase between 8 and 16 weeks of age (weeks 5 and 13 of the experiment). The increase in infiltrating immune cells is particularly dramatic, as visualized by CD45 staining. Both fibrosis and immune infiltrates are less abundant in the high-dose sirolimus–treated group and tissue architecture seems to be better preserved; however, it is notable that the fibrotic index was not significantly different from untreated mutants because of one mouse with high levels of fibrosis. Furthermore, fibrosis is significantly lower in the late high-dose treatment group compared with mice untreated at 5 weeks (the starting point of late treatment) (Figure 4, G and H and Supplemental Figure 4).

Late Treatment

In the group in which high-dose sirolimus was started at 11 weeks of age (week 8 of the experiment), Pkd1nl,nl mice showed a significant reduction in the 2KW/BW ratio and cystic index (1.99%±0.29%; P=0.0019) (Figure 2C) compared with the untreated group (20.10%±5.18%; P=0.036) (Figure 2D). These mice received control food for 8 weeks and were then switched to a high-dose sirolimus diet for the next 8 weeks.

Both fibrosis and immune infiltrates were significantly less abundant in this late-start group and were similar to the long-term high-dose treatment group (Figure 4, G and H and Supplemental Figures 2 and 4, B and D).

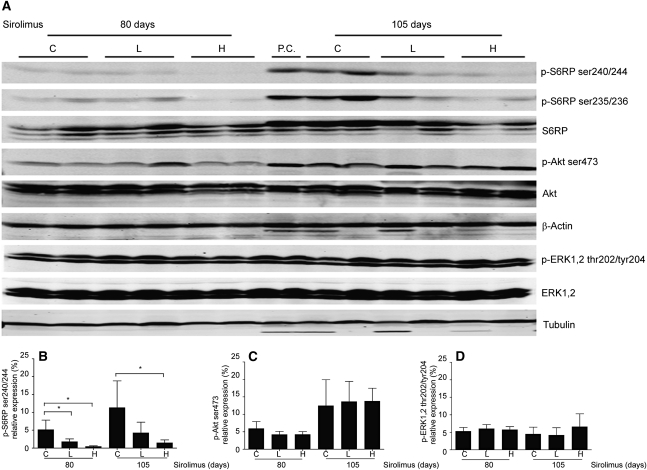

Sirolimus Treatment Reduces mTOR Signaling

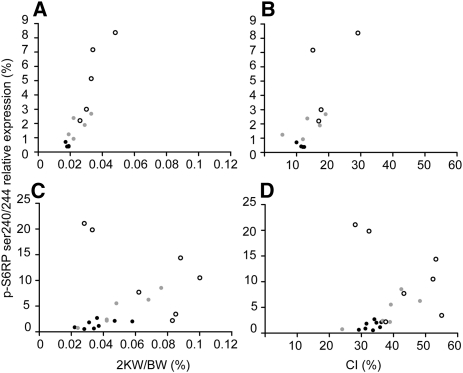

At early stages of PKD, mTOR signaling was strongly inhibited by a high dose of sirolimus. Staining for p-S6RpSer240/244 was very weak to negative in iKsp-Pkd1del mice treated with high-dose sirolimus (iKsp-Pkd1del, 80 days treatment) (Figure 3, H and I) and was moderately reduced with low-dose treatment (not shown). Concomitantly, Western blot analysis showed strongly reduced levels of p-S6RpSer240/244 for high-dose (P=0.016) and low-dose treatment (P=0.044) compared with untreated controls (Figure 5, A and B). After long-term treatment, p-S6RpSer240/244 levels increased in all groups compared with short-term treatment but were significantly lower upon high-dose treatment (P=0.013) compared with controls. Low-dose treatment resulted in lower, although more variable, levels of p-S6RpSer240/244 and cystic phenotype. In general, the progressiveness of the cystic phenotype correlated well with the S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios (i.e., mice with the lowest S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios showed the lowest 2KW/BW ratios and cystic indices) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Altered signaling upon sirolimus treatment. (A) Western blots of total kidney lysates from controls and iKsp-Pkd1del mice receiving 80 or 105 days of treatment (see Figure 1) with high-dose (100 mg/kg chow) or low-dose sirolimus (10 mg/kg chow). Ratios for (B) p-S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp, (C) p-Aktser473/total Akt, and (D) p-ERK1/2Thr202/Tyr204/total ERK obtained by densitometric analysis of Western blots. Mean ± SD indicated for high-dose/short-term (n=4), low-dose/short-term (n=5), untreated/short-term (n=5), high-dose/long-term (n=8), low-dose/long-term (n=6), and untreated/long-term (n=7) groups. *P<0.05 compared with untreated mutants. C, controls; L, low-dose sirolimus; H, high-dose sirolimus.

Figure 6.

Association between the S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios and the cystic phenotype. Association diagrams between the S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios and (A) 2KW/BW ratio (Rs=0.914, P<0.01; n=14) or (B) cystic index (Rs=0.731, P<0.01; n=13) after short-term sirolimus treatment. Association between the S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios and (C) 2KW/BW ratio (Rs=0.508, P<0.05; n=21) or (D) cystic index (rs=0.503, P<0.05; n=21) after long-term sirolimus treatment. White dots, untreated mice; gray dots, low-dose treatment; black dots, high-dose treatment. CI, cystic index.

Similar data were obtained with p-S6RpSer235/236 (Figure 5A). Total S6Rp levels were not significantly different between the groups.

After 80 days, tissue sections of untreated iKsp-Pkd1del mice showed groups of small or moderately sized cysts and dilated tubules in cortex that were partly p-S6RpSer240/244 positive, as well as a subset that was entirely strongly positive (Figure 3H). In addition, many positive dilated tubules were observed in the corticomedullary region, although there was variation in intensity (Supplemental Figure 2C). A similar expression pattern was observed in untreated mice after 105 days. Overall, one-third of cysts and dilated tubules were entirely positive, one-third were partially positive, and one-third were negative for p-S6RpSer240/244 (Figure 3J). Upon high-dose sirolimus treatment, the number of positive cysts and tubules was lower, as was the number of positive cells per cyst. The majority of small cysts and dilated tubules were negative (Figure 3L). Low-dose treatment was more similar to untreated mutants than to high-dose treated animals, although with variability in intensities (Figure 3K).

A similar pattern was observed in the Pkd1nl,nl mice. Larger cysts showed a few strongly positive cells and in all small and medium-sized cysts staining varied from negative to entirely positive; however, the majority had few positive cells (not shown). Interstitial cells, around cysts, are often also p-S6RpSer240/244 positive. There are small areas of preserved tissue in the cortex. As in wild-type kidneys, mTOR activity was seen in all segments but was found most frequently in distal (dilated) tubules (Supplemental Figure 5, E and F). Less than half of the largest cysts were partially positive, frequently with a small number of cells that are sometimes intensely positive (Supplemental Figure 5B). In general, the inner medulla was virtually negative in both models at all time points. Strong staining was observed in immune cell infiltrate regions.

Our data suggest that Pkd1 gene disruption induces mTOR signaling at early stages and that sirolimus can slow down but not prevent increased signaling over time. We studied other signaling molecules reported to be affected in PKD that also influence mTOR activity, such as activation of Akt and ERK1/2.27

Using Western blot analysis, low levels of p-AktSer473 were detected in mildly affected tissues (untreated, 80 days), which were similar upon low- and high-dose treatment (Figure 5, A and C). The p-Aktser473 levels increased in all groups over time. In distal tubules, a more intense signal was generally observed in collecting ducts and in some small cysts, and weak staining was detected in the remaining nephron segments and cysts (Figure 3, M–O). Analysis of sequential sections stained for p-S6RpSer240/244 and p-AktSer473 showed that many of the proximal cysts positive for p-S6RpSer240/244 were negative for p-AktSer473 and vice versa, as was particularly evident in iKsp-Pkd1del mice (Figure 3, P and Q). Although some (dilated) distal tubules or collecting ducts that stained positive for p-S6RpSer240/244 were negative for p-AktSer473, the majority of these nephron segments were also weak to moderately positive for p-AktSer473. The inner medulla was positively stained (not shown).

Levels of p-ERKThr202/Tyr204 were not significantly different between the three groups after short- or long-term treatment (Figure 5D). Most activity was seen in distal, dilated, and undilated tubules and in some moderately sized cysts, as indicated by expression of p-p90RSKThr 359/Ser363. Note that p-S6RpSer240/244–positive segments mostly did not express p-p90RSKThr 359/Ser363 (Figure 3R).

Discussion

A high dose of sirolimus, given in the early stage of disease, strongly reduced cyst formation and 2KW/BW ratios in an inducible Pkd1-deletion mouse model for ADPKD. When a conventional low dose of sirolimus was given (approximately 3 ng/ml in blood), the cystic index and 2KW/BW ratios were more variable and were generally not significantly different from untreated mutants. When treatment was initiated at a more advanced stage of disease, even a high-dose treatment lacked significant effects on cyst formation.

In the second model, Pkd1nl,nl mice had reduced levels of Pkd1 gene expression and enlarged kidneys25 with areas of large cysts intermixed with relatively normal renal parenchyma. In this mouse model, the size of cysts decreased, the cysts collapsed, and the amount of fibrosis and immune infiltrates gradually increased over time (Happé et al., 2011, unpublished data) between 4 and 16 weeks. Therapeutic effects can particularly be analyzed on alterations characteristic for progressive stages of PKD in these mice. Interestingly, high- and low-dose sirolimus treatment in the early disease stage significantly accelerated cyst regression. In addition, high-dose treatment started at a more advanced stage accelerated cyst regression (e.g., 2KW/BW ratios and cystic indices were strongly reduced). A slight, but not significant, increase in apoptosis in animals treated for 1 or 5 weeks may explain the accelerated regression. We saw a significant reduction in apoptosis only after cyst regression at 13 weeks, which may reflect the fact that the treated kidneys regressed faster (Supplemental Figure 6, A and B).

Our data indicate that mTOR inhibitors may work effectively against cyst formation and disease progression when used at a high enough dose and with adequate timing. It should be noted, however, that although the two models used in this study are orthologous to the main form of human ADPKD, both have characteristics that are different from those in the human disease. In ADPKD, phenotypic manifestations such as increased proliferation, extracellular matrix production, and altered fluid transport occur due to sporadic (damage) events accumulating over time, leading to progressive renal disease. In the inducible Pkd1-deletion mouse model, gene inactivation is synchronized and cyst formation is more rapid than in humans. In Pkd1nl,nl mice, there is an early onset of disease that overlaps the phenotype of patients carrying two missense mutations (incompletely penetrant alleles) and ADPKD.28

Two clinical trials recently tested the effects of mTOR inhibitors in patients.17,18 In a study by Walz et al., patients with advanced ADPKD (stage 3 or 4 CKD), treated with everolimus for 2 years, showed a reduced increase in renal volume without improvement in renal function over time. Moreover, the estimated GFR disappointingly declined more rapidly in the everolimus group than in the placebo group.17 It was suggested that a lack of beneficial effect may be because the renal tissue was already significantly and irreversibly damaged.29 This is in line with our observations in the groups of late-start treatment in iKsp-Pkd1del mice.

In a study by Serra et al., 18 months of sirolimus treatment in early stage ADPKD patients (stage 1 and 2) did not slow down the increase in renal volume.18 Interestingly, the effects we observed with low-dose sirolimus treatment seem to mirror the results from these PKD clinical trials. The blood sirolimus levels measured in mice receiving a low dose of approximately 3 ng/ml (both models) are similar to doses used in patients after transplantation and in the above-mentioned clinical trials. The blood sirolimus levels measured in mice receiving a high dose, however, are roughly 10–20 times higher (model 1, 23 ng/ml; model 2, 57 ng/ml). It should be noted that the high dose is well tolerated in the mice but is beyond the levels that could be tolerated by humans. Previous studies also showed beneficial effects of rapamycin in two orthologous PKD mouse models.30,31 High-dose sirolimus (blood level of 22 ng/ml) has been shown to reduce cyst growth in Pkd2WS25/- mice without improvement of renal function,31 whereas rapamycin reduced cyst growth and improved renal function in a conditional Pkd1-knockout model. In this model, drug levels in circulation were not measured.30

Similar to findings in the clinical studies, a low-dose mTOR inhibitor is not consistently effective in inhibiting cyst formation but tends to promote cyst regression. Supporting the latter, patients receiving mTOR inhibitors after transplantation in retrospective studies have shown decreasing renal and liver cystic volumes.10,32 The effect of mTOR inhibition on cyst volume regression may be caused by increased apoptosis and/or by a potential effect on fluid reabsorption as suggested for fetal lung epithelia.30,33 Nonetheless, our results support the concept of cyst regression by mTOR inhibitors when used at high enough concentrations.

At later stages of PKD, a dramatic increase in interstitial fibrosis and infiltrating immune cells can be seen in patients and in Pkd1nl,nl mice. We observed a strong decrease in infiltrates and fibrosis in Pkd1nl,nl mice receiving high-dose sirolimus, but not in the conventional low-dose–treated mice. Strikingly, reduced fibrosis was observed in Pkd1nl,nl mice receiving late treatment. A possible explanation could be that the balance between profibrotic and antifibrotic factors is shifted toward antifibrosis.34 On the other hand, we did not measure Sirius red staining intensity but only measured the stained area, which in combination with cyst regression may also affect the results.

One of the purposes of our study was to examine the importance of a dose-related clinical effect. We observed that bioavailability was different between the two models for the high-dose treatment. A likely explanation is the difference in genetic background of the mouse strains. In addition, there is large patient variability in the oral bioavailability of rapamycin. This is partly due to differences in metabolism by cytochrome P4503A4 (CYP3A4) and in countertransport by a multidrug efflux pump, intestinal P-glycoprotein.35 The latter indicates that drug blood levels are not sufficient indicators for bioactivity. Bioavailability of rapamycin also depends on the administration protocol, such as intraperitoneal injection, gavage, or food.36 Because our experiments indicate that the sirolimus dose is critical to achieve an optimal effect on PKD in mice, it is difficult to compare our data with a previously published study on the Pkd1-deletion model, for which the blood levels have not been reported and intraperitoneal injection was used.30

Our results indicate that low-dose sirolimus does not significantly reduce mTOR activity in renal epithelia over time and that levels of the p-S6RpSer240/244 varied between kidneys, similarly to the cystic phenotype. The progressiveness of the cystic phenotype generally correlated well with the S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios. Consistent with our experimental data in the low-dose group are results from a reported clinical case showing no clear differences in total kidney and cyst volumes between the two kidneys of an ADPKD donor that were engrafted in two different recipients, one of them receiving and the other not receiving immunosuppressive sirolimus treatment for 5 years. Interestingly, the mean blood sirolimus level of 3.68 ng/ml is similar to our low-dose treatment. It is also interesting that biopsies from the sirolimus-treated patient did not show reduced mTOR activity.37 These experimental and clinical results suggest that the bioavailability of sirolimus with regard to inhibiting mTOR pathway signaling is critical and, in these cases, likely insufficient.

High-dose sirolimus effectively reduced mTOR activity, especially in short-term treatment. However, long-term treatment eventually could not prevent cyst formation, which correlated with the increase in renal p-S6Rp levels with time. This was not caused by inadequate intake because blood levels were not reduced over time (data not shown). Rather, negative feed-back loops mediated by effector molecules downstream of mTOR (e.g., p-S6 kinase) onto key upstream signaling molecules (e.g., PI3K),27,38 as well as cross-talk with other signaling cascades, may eventually diminish the total mTOR activity. It should also be considered that other related signaling processes driving cystogenesis may become more important during disease progression. In addition, our immunohistochemical data for p-S6RpSer240/244 indicate that a substantial proportion of cysts were almost negative. This could either be a reflection of cellular variations of mTOR activity in time or because the signaling pattern is more complex. Therefore, it may be necessary to implement complementary therapeutic molecular targeting strategies when using mTOR inhibitors as long-term PKD therapy.

Adverse side effects of mTOR inhibitors will be a concern if high doses of the medication are needed in the long term; however, there is less concern in this regard in the short term, as shown in a shorter, 6-month feasibility trial.16 It is well known that mTOR inhibitors often have a wide range of side effects, including increased cholesterol and triglyceride levels, as we also found in our experimental study (Supplemental Material).

The cell functions via the complex network of signaling cascades and polycystin-1 seem to be a key regulator. Therefore, pathologic alterations are accompanied by changes in these cellular signaling pathways during disease progression. This concept implies that targeting inhibition of cyst formation via various signaling pathways simultaneously, either by combination therapy or by a multi-target drug, may overcome decreased drug efficacy after prolonged administration and also reduce side effects.12 Because the cystic phenotype correlates with the level of mTOR activity in diseased kidneys, increasing bioavailability using new analogs or directing mTOR inhibitors more specifically to kidneys may improve therapeutic effects against PKD in the future.

Concise Methods

Experimental Animals

The inducible kidney-specific Pkd1-deletion mouse model (tam-KspCad-CreERT2; Pkd1lox2-11; lox2-11, referred to as iKsp-Pkd1del) and tamoxifen treatments were previously described.26,39 The Pkd1 gene was inactivated in male adult mice at postnatal days 38–40 by oral administration of 5 mg of tamoxifen per day (Sigma) for 3 consecutive days.

The mouse model with the hypomorphic Pkd1 allele, Pkd1nl,nl, was previously described.25 Mice were crossed back to a full C57BL/6J (Bl6) genetic background and to a full 129Ola/Hsd (Ola) genetic background. By breeding Bl6 male × Ola female, F1 mice with a 50/50 genetic background of Bl6 and Ola were generated, and Pkd1nl,nl male and female mice were used for these experiments. These mice develop severe bilateral cystic kidneys, extensive renal fibrosis, and progressive immune cell infiltration; however, they exhibit increased survival compared with the previously published Bl6 model (Happé et al., 2011, unpublished data).

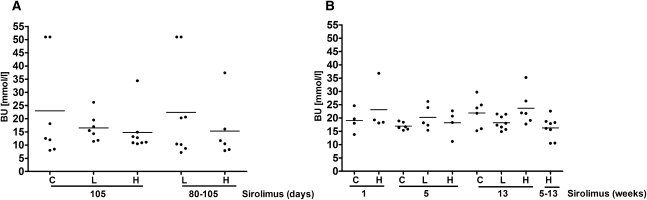

Mice were sacrificed at previously determined time points (Figure 1) or when BU concentrations were >20 mmol/L, indicating renal failure (Figure 7). BU concentrations were measured using the Reflotron Plus system (Roche Diagnostics). Renal tissues were harvested from all animals and extrarenal tissues were collected from iKsp-Pkd1del mice after 105 days of treatment and from Pkd1nl,nl mice after 5 weeks of treatment (n=3 per time point).

Figure 7.

BU levels in iKsp-Pkd1del and Pkd1nl,nl mice. BU measured at moment of sacrifice in (A) iKsp-Pkd1del mice receiving no treatment, after long-term and late sirolimus treatment, and in (B) Pkd1nl,nl mice receiving high-dose and low-dose sirolimus for 1, 5, and 13 weeks and from weeks 5 to 13. Data are presented as mean values.

The experiments were approved by the local animal experimental committee of the Leiden University Medical Center and the Commission on Biotechnology in Animals of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture.

Sirolimus Treatment

Male iKsp-Pkd1del mice were initially fed regular rodent chow. Approximately 7 days after tamoxifen administration, animals in the treatment groups received sirolimus-supplemented chow (Wyeth Pharma) in a dose of 100 mg/kg chow (high dose) or 10 mg/kg chow (low dose). Sirolimus was mixed with regular chow (SSNIFF Spezialdiaeten). Control mice were fed the same chow without supplementation. Mice were treated for 79 days (approximately 80 days) or 105 days. In addition, sirolimus treatment was started in two groups at 87 days upon Pkd1 gene disruption and the animals were treated with either high- or low-dose sirolimus for 105–110 days (Figure 1A).

In Pkd1nl,nl male and female mice, treatment was started upon weaning at day 21 (Figure 1B) and mice were fed on high-dose, low-dose, or control chow for 1, 5, or 13 weeks. In the late-start treatment groups, mice received control chow for the first 8 weeks and were switched to the high dose for the next 8 weeks. Mice were sacrificed at 4, 8, and 16 weeks of age.

Sirolimus Blood Concentrations

Blood samples for sirolimus concentration measurements were obtained from the tail vein at several time points for both models. Samples were collected with EDTA-dipotassium salt-coated capillary tubes (Sarstedt) and sirolimus concentrations were determined using standardized high-performance liquid chromatography methods.

Total Cholesterol, Triglycerides, and Hemoglobin

Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein of the conditional model at 6, 14, or 16 weeks of treatment, or from the hypomorph model after 8 and 13 weeks of treatment. Samples were collected with capillary tubes coated with lithium and heparin (Sarstedt), and plasma was isolated by 5-minute centrifugation at 8000 rpm. Samples were stored at −20°C, and triglyceride and total cholesterol levels were assayed using commercially available kits (1488872 and 236691; Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Samples were processed using a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices) and the data were analyzed using SoftMax Pro V5 software.

Hemoglobin concentrations were measured using the Reflotron Plus (Roche Diagnostics).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues including kidney, spleen, liver, mesenteric, submandibular, and iliac lymph nodes were harvested and fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde solution overnight (O/N), embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Paraffin-embedded kidney sections (4 μm) were processed with standard periodic acid–Schiff and Sirius red staining procedures. For immunohistochemical analyses, sections were deparaffinized and processed for heat-mediated antigen retrieval, and 0.01M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) was used for anti-phospho-S6Rp (Ser 240/244), anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-phospho-p90RSK (Thr 359/Ser363), and Ki67.

After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity for 20 minutes in 0.1% H2O2, sections were pre-incubated for 1 hour with 5% normal goat serum in 1% BSA in PBS and were further incubated with primary antibody O/N. After incubation with secondary antibody, sections were exposed to rabbit envision horseradish peroxidase (Dako Cytomation) for 30 minutes, and immune reactions were visualized by incubation diaminobenzidine as a chromogen for 10 minutes. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (1:4), dehydrated, and mounted.

Snap-frozen kidneys were sectioned (4 μm), fixed with acetone for 10 minutes, and incubated for 1 hour with anti-CD45, followed by 30 minutes incubation with secondary antibody and 10 minutes incubation with diaminobenzidine.

Cystic Index Analyses

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained kidney cross-sections were used to determine the cystic index. Specimens were scanned in a Panoramic Midi Tissue scanner (3D Histech Ltd) and were processed using a MIRAX Viewer (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH) at ×1 magnification. The renal tissue area was determined using Image J software (National Institutes of Health) and images were than edited for the extraspecimen area, followed by measurement of only the cystic lumen area. The cystic index for each mouse was calculated as a percentage of the area of cystic lumen divided by the area of renal tissue plus lumen.

Fibrosis and Immune Cell Infiltrate Profile Analyses

Paraffin-embedded renal sections of 5- and 13-week–treated Pkd1nl,nl mice were stained for Sirius red, scanned in a Panoramic Midi Tissue scanner and processed using a MIRAX Viewer at ×1 magnification. Blood vessels and regions of papilla were excluded from analyses. Images were analyzed using Image J software and the amount of fibrosis was calculated as the percentage of Sirius red signal in total tissue area.

For immune cell infiltration analyses, renal cryosections of 13-week–treated Pkd1nl,nl mice were stained for CD45, and eight images (×20 magnification) were taken per mouse using a spectral imaging microscope (Nuance Multispectral Imaging System; Cambridge Research & Instrumentation Inc). Images were analyzed using Image J software and areas of immune cell infiltration and total specimen area were determined for each image. The percentage of immune cell infiltrates was calculated as the percentage of CD45 signal in total image tissue for each mouse.

Western Blot Analyses

Snap-frozen kidneys were ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle and protein extract was prepared in Fos-RIPA lyses buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Na-DOC, 1% Triton-X-100, 1% NP-40) with phosphatase inhibitors 50 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4, as well as a 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After three 5-second pulses of sonication on ice, samples were incubated for 45 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was collected after 10 minutes of centrifugation at 14,000×g and protein concentrations were determined by the BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Thirty micrograms of total kidney lysate was used for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc) were blocked for 1 hour in 4% nonfat dry milk in PBS and incubated O/N at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in 5% BSA in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, followed by 1 hour incubation with secondary antibodies. Signals were visualized and quantified for integrated intensity using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Westburg).

Levels of p-S6Rp, S6Rp, p-Akt, and Akt were corrected for α-tubulin as well as levels of p-ERK1/2Thr202/Tyr204 and total ERK for β-actin.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-p-S6Rp (Ser 240/244) (Cell Signaling #2215); anti-p-S6Rp (ser235/236) (Cell Signaling #2211); anti-S6Rp (Cell Signaling 5G10 #2217); anti-p-ERK 1,2 (Thr 202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling #9101); anti-ERK1 (k-23) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-94); anti-p-p90 RSK (Thr 359/Ser363) (Cell Signaling #9344); anti-p-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling #3787); anti-p-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling #9271); mixture of anti-Akt1 (Upstate #07-416); anti-Akt2 (Upstate #07-372); rat anti-mouse CD45 (Pharmingen #0111D 30-F11); rabbit anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling #4967); mouse anti-α-tubulin (Calbiochem #CP06); anti-Ki-67 (Nova Castra); and anti-caspase-3 (Becton Dickinson). The following secondary antibodies were used: goat-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (DyLight 800 conjugated); goat-anti-mouse IgG (H+L), (DyLight 680 conjugated; PerbioScience #35571 and 35518); and rabbit anti-rat IgG horseradish peroxidase (Dako #0450).

Statistical Analyses

For all parameters, statistical significance was determined by two-sample t tests after testing equality of variances using the F test. The 2KW/BW ratios and cystic indices were also analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Spearman’s test was used to determine associations between the S6RpSer240/244/total S6Rp ratios and 2KW/BW ratios or cystic indices.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frans Prins for assistance with image analysis, Amanda Pronk and Sjoerd van den Berg for cholesterol and lipid analysis, Daniela Salvatori for histopathology analysis, Johan W. de Fijter for discussion, and Bruno Guigas for antibodies.

This research was supported by grants from HSP Huygens (HSP-HP.07/1164-G) and the Polycystic Kidney Disease Research Foundation (175G08a).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2011040340/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wilson PD: Polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 350: 151–164, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheffers MS, van der Bent P, Prins F, Spruit L, Breuning MH, Litvinov SV, de Heer E, Peters DJM: Polycystin-1, the product of the polycystic kidney disease 1 gene, co-localizes with desmosomes in MDCK cells. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2743–2750, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, Elia AE, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J: Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet 33: 129–137, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu AS, Kanzawa SA, Usorov A, Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Peters DJ: Tight junction composition is altered in the epithelium of polycystic kidneys. J Pathol 216: 120–128, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharif-Naeini R, Folgering JHA, Bichet D, Duprat F, Lauritzen I, Arhatte M, Jodar M, Dedman A, Chatelain FC, Schulte U, Retailleau K, Loufrani L, Patel A, Sachs F, Delmas P, Peters DJ, Honoré E: Polycystin-1 and -2 dosage regulates pressure sensing. Cell 139: 587–596, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi T, Nagao S, Wallace DP, Belibi FA, Cowley BD, Pelling JC, Grantham JJ: Cyclic AMP activates B-Raf and ERK in cyst epithelial cells from autosomal-dominant polycystic kidneys. Kidney Int 63: 1983–1994, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnould T, Kim E, Tsiokas L, Jochimsen F, Grüning W, Chang JD, Walz G: The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene product mediates protein kinase C alpha-dependent and c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent activation of the transcription factor AP-1. J Biol Chem 273: 6013–6018, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Boletta A, Liu L, Qian F, Xu PN, Germino FJ, Germino GG: PKD1 induces p21(waf1) and regulation of the cell cycle via direct activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a process requiring PKD2. Cell 109: 157–168, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boca M, Distefano G, Qian F, Bhunia AK, Germino GG, Boletta A: Polycystin-1 induces resistance to apoptosis through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 637–647, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shillingford JM, Murcia NS, Larson CH, Low SH, Hedgepeth R, Brown N, Flask CA, Novick AC, Goldfarb DA, Kramer-Zucker A, Walz G, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Weimbs T: The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 5466–5471, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassane S, Leonhard WN, van der Wal A, Hawinkels LJ, Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, ten Dijke P, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ: Elevated TGFbeta-Smad signalling in experimental Pkd1 models and human patients with polycystic kidney disease. J Pathol 222: 21–31, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonhard WN, van der Wal A, Novalic Z, Kunnen SJ, Gansevoort RT, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ: Curcumin inhibits cystogenesis by simultaneous interference of multiple signaling pathways: In vivo evidence from a Pkd1-deletion model. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F1193–F1202, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres VE, Harris PC: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The last 3 years. Kidney Int 76: 149–168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Vanslembrouck R, van Oijen MG, Hoffmann AL, Dekker HM, de Man RA, Drenth JP: Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 137: 1661–1668, e1–e2, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, Kubly VJ, Bergstralh EJ, Li X, Kim B, King BF, Glockner J, Holmes DR, 3rd, Rossetti S, Harris PC, LaRusso NF, Torres VE: Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1052–1061, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perico N, Antiga L, Caroli A, Ruggenenti P, Fasolini G, Cafaro M, Ondei P, Rubis N, Diadei O, Gherardi G, Prandini S, Panozo A, Bravo RF, Carminati S, De Leon FR, Gaspari F, Cortinovis M, Motterlini N, Ene-Iordache B, Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G: Sirolimus therapy to halt the progression of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1031–1040, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walz G, Budde K, Mannaa M, Nürnberger J, Wanner C, Sommerer C, Kunzendorf U, Banas B, Hörl WH, Obermüller N, Arns W, Pavenstädt H, Gaedeke J, Büchert M, May C, Gschaidmeier H, Kramer S, Eckardt KU: Everolimus in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 363: 830–840, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serra AL, Poster D, Kistler AD, Krauer F, Raina S, Young J, Rentsch KM, Spanaus KS, Senn O, Kristanto P, Scheffel H, Weishaupt D, Wüthrich RP: Sirolimus and kidney growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 363: 820–829, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torres VE, Meijer E, Bae KT, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang JJ, Czerwiec FS: Rationale and design of the TEMPO (Tolvaptan Efficacy and Safety in Management of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and Its Outcomes) 3-4 Study. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 692–699, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN: TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124: 471–484, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu M, Arcaro A, Varga Z, Vogetseder A, Le Hir M, Wüthrich RP, Serra AL: Pulse mTOR inhibitor treatment effectively controls cyst growth but leads to severe parenchymal and glomerular hypertrophy in rat polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1597–F1605, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao Y, Kim J, Schrier RW, Edelstein CL: Rapamycin markedly slows disease progression in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 46–51, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zafar I, Belibi FA, He Z, Edelstein CL: Long-term rapamycin therapy in the Han:SPRD rat model of polycystic kidney disease (PKD). Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2349–2353, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wüthrich RP, Serra AL: Mammalian target of rapamycin and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Transplant Proc 41[Suppl]: S18–S20, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Dauwerse JG, Baelde HJ, Leonhard WN, van de Wal A, Ward CJ, Verbeek S, Deruiter MC, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ: Lowering of Pkd1 expression is sufficient to cause polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet 13: 3069–3077, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Leonhard WN, van der Wal A, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ: Kidney-specific inactivation of the Pkd1 gene induces rapid cyst formation in developing kidneys and a slow onset of disease in adult mice. Hum Mol Genet 16: 3188–3196, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Distefano G, Boca M, Rowe I, Wodarczyk C, Ma L, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Pandolfi PP, Boletta A: Polycystin-1 regulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent phosphorylation of tuberin to control cell size through mTOR and its downstream effectors S6K and 4EBP1. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2359–2371, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vujic M, Heyer CM, Ars E, Hopp K, Markoff A, Orndal C, Rudenhed B, Nasr SH, Torres VE, Torra R, Bogdanova N, Harris PC: Incompletely penetrant PKD1 alleles mimic the renal manifestations of ARPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1097–1102, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grantham JJ, Chapman AB, Torres VE: Volume progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The major factor determining clinical outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 148–157, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shillingford JM, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Weimbs T: Rapamycin ameliorates PKD resulting from conditional inactivation of Pkd1. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 489–497, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zafar I, Ravichandran K, Belibi FA, Doctor RB, Edelstein CL: Sirolimus attenuates disease progression in an orthologous mouse model of human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 78: 754–761, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian Q, Du H, King BF, Kumar S, Dean PG, Cosio FG, Torres VE: Sirolimus reduces polycystic liver volume in ADPKD patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 631–638, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otulakowski G, Duan W, Gandhi S, O’brodovich H: Steroid and oxygen effects on eIF4F complex, mTOR, and ENaC translation in fetal lung epithelia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 457–466, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bridle KR, Popa C, Morgan ML, Sobbe AL, Clouston AD, Fletcher LM, Crawford DH: Rapamycin inhibits hepatic fibrosis in rats by attenuating multiple profibrogenic pathways. Liver Transpl 15: 1315–1324, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rangan GK, Nguyen T, Mainra R, Succar L, Schwensen KG, Burgess JS, Ho KO: Therapeutic role of sirolimus in non-transplant kidney disease. Pharmacol Ther 123: 187–206, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Gruijl FR, Koehl GE, Voskamp P, Strik A, Rebel HG, Gaumann A, de Fijter JW, Tensen CP, Bavinck JN, Geissler EK: Early and late effects of the immunosuppressants rapamycin and mycophenolate mofetil on UV carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer 127: 796–804, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canaud G, Knebelmann B, Harris PC, Vrtovsnik F, Correas JM, Pallet N, Heyer CM, Letavernier E, Bienaimé F, Thervet E, Martinez F, Terzi F, Legendre C: Therapeutic mTOR inhibition in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: What is the appropriate serum level? Am J Transplant 10: 1701–1706, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Efeyan A, Sabatini DM: mTOR and cancer: Many loops in one pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22: 169–176, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Leonhard WN, van de Wal A, Breuning MH, Verbeek S, de Heer E, Peters DJ: Transgenic mice expressing tamoxifen-inducible Cre for somatic gene modification in renal epithelial cells. Genesis 44: 225–232, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]