Abstract

Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) is an abundant protein of Escherichia coli and other enterobacteria with a multitude of functions. Although the structural features and porin function of OmpA were well studied, its role in the pathogenesis of various bacterial infections has been emerging for the past decade. The four extracellular loops of OmpA interact with a variety of host tissues for adhesion, invasion and evasion of host-defense mechanisms. This review describes how various regions present in the extracellular loops of OmpA contribute to the pathogenesis of neonatal meningitis induced by E. coli K1 and for many other functions. In addition, the function of OmpA like proteins such as OprF of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is also discussed herein.

Introduction

Bacterial infections contribute to significant mortality throughout the world. Globally important diseases such as tuberculosis kill millions of people every year. Other infections such as pneumonia, which can be caused by Streptococcus and Pseudomonas and food borne illnesses due to Shigella, Salmonella and Campylobacter, tetanus, typhoid, diphtheria, syphilis leprosy and meningitis contribute to high morbidity rates. In the USA, 71% of urinary tract infections, 65% of pneumonia episodes, 34% of surgical site infections, and 24% of bloodstream infections were due to Gram-negative bacilli. The rates of nosocomial infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria are even higher in many parts of the world. Since the emergence of antibiotic resistant strains is problematic to treat these infections, understanding the pathogeneses of various diseases by these bacteria would yield information to develop new preventative or therapeutic strategies. Bacterial pathogens have several surface structures that potentially interact with host tissues for attaching to and invasion, which include pili or fimbriae, outer membrane proteins (OMPs) and various secretion systems. Gram-negative bacteria contain several classes of OMPs that form monomeric or trimeric barrels to facilitate the transport of nutrients into the cell.

Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) is a multi-functional major outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli and other Enterobacteriaceae family. OmpA is a highly conserved protein among Gram-negative bacteria throughout evolution. In addition to its role as a structural protein, OmpA serves as a receptor for several bacteriocins namely colicin U, colicin L and bacteriocin 28b. It also serves as a receptor for several bacteriophages such as K3, Ox2 and M1. Furthermore, OmpA interaction with F-plasmid encoded outer membrane protein TraN is required for conjugal mating. The current understanding of the structure and assembly of OmpA is reviewed in previous sections and elsewhere [1,2]. OmpA is a beta-barrel protein that contains four extracellular loops and, a comparison of sequence similarities in the extracellular portions of various Gram-negative bacteria is shown in Fig. 1. Recently, OmpA has been shown to exist as two different allelic forms, ompA1 and ompA2. These two alleles have specific differences in the amino acids especially in loop 2 and 3 [3]. Here, the function of OmpA in the pathogenesis of various diseases by different bacteria is reviewed.

Fig. 1. Sequence homology of OmpA from various Gram-negative bacteria.

Representative pathogens for which OmpA has been shown to play a role in virulence were subjected to protein sequence alignment using the online ClustalW2 alignment tool (www.ebi.ac.uk/ClustalW2). The 4 loops of OmpA are shown within boxes and difference in amino acid sequences are highlighted in yellow. Cleavage site of the mature protein is indicated by arrowhead.

Pathogenesis of E. coli K1 induced neonatal meningitis – All round action of OmpA

Bacterial meningitis in the neonatal population is a serious central nervous system (CNS) infection distinguished by a severe inflammation of the meninges and the subarachnoid space. The mortality rates associated with this disease range from 20 to 30% of infected infants and reaches 100% if untreated. Though antibiotic treatment reduces mortality rates, 50% of survivors suffer neurological sequelae that include mental retardation, cortical blindness and hearing impairment. E. coli K1 is one of the prominent pathogens that cause meningitis in neonates. The bacterium colonizes nasopharyngeal or gastrointestinal sites initially and penetrates into circulation in which it multiplies to reach high-grade bacteremia. Subsequently, E. coli K1 interacts with brain microvascular endothelial cells, which comprises the lining of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), to bind to and invade. During these steps, the bacteria must evade host-defense mechanisms for which E. coli K1 has developed a variety of strategies for survival.

E. coli K1 OmpA role in evasion of complement attack

The first report for the role of OmpA in virulence was demonstrated in a neonatal rat model of E. coli K1 meningitis and by far the most extensively studied. E. coli K1 lacking OmpA expression were inefficient in inducing bacteremia in neonatal rats and embryonated chick embryo [4]. Serum survival is an important initial step for E. coli K1 to reach a threshold level of bacteremia and for subsequent crossing of the BBB. Several bacterial pathogens have developed strategies to evade complement mediated killing by interfering with complement activation [5]. Our studies have demonstrated that the serum resistance of E. coli K1 is due to OmpA binding to C4b binding protein (C4BP), which is the predominant serum inhibitor of C3b activation via the classical pathway. C4BP that bound to E. coli K1 acts a cofactor in Factor I-mediated cleavage of C4b to C4d and increases the dissociation of the classical pathway C3 convertase. The N-terminal extracellular loops of OmpA interact with complement control protein module 3 (CCP3) found in the alpha chain of C4BP to prevent complement-mediated killing [6]. Of note, synthetic peptides that represent sequences of CCP3 when pre-incubated with E. coli K1 increased serum killing. Logarithmic phase (LP) cultures of OmpA+ E. coli were more efficient in serum resistance than post-LP cultures. Increased binding of LP OmpA+ E. coli to C4BP is responsible for this resistance to serum killing due to concomitant decrease in C3b formation and other downstream proteins required for bacteriolysis [7].

Recent studies have demonstrated that mutations in loops 1, 2 and 4 of OmpA to alanines, three amino acids at a time in different positions of each of the loops, are involved in resisting serum bactericidal activity by E. coli K1 as these mutants were unable to bind C4BP efficiently (Fig. 2). Of note, mutation of three residues in Loop 4 increased the virulence of E. coli in the newborn mouse model of meningitis. Loop 4 mutant E. coli K1 caused high-level bacteremia in relatively shorter time than the wild type E. coli K1, indicating that this mutant is surviving efficiently during the initial stages of infection. In addition, Loop 4-mutant also induces greater production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12, and recruited more microglia, B cells, macrophages and granulocytes compared to E. coli K1 to the sites of infection. Therefore, it is possible that the binding of a serum protein that initiates serum killing depends on Loop 4 sequence during the initial stages of infection. Once the bacteria survive in serum, evasion of immunocyte-mediated killing is the next step for survival.

Fig. 2. C4b-binding protein interaction with E. coli K1 that express mutant OmpA.

Two dimensional structure of OmpA depicting regions of three or four amino acids mutated to alanines (A). E. coli K1 expressing either wild type or mutated OmpA were incubated with C4bp for 30 min, washed and the bound proteins were evaluated by flow cytometry. Previously published in J. Biol. Chem. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M110.178236

Role of OmpA in E. coli interaction with immune cells

Neutrophils or polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) provide first line of defense against invading microorganisms. Binding of microorganisms to PMN surface-receptors generates signals that regulate the response of the PMNs for killing of the microbial intruder, which requires delivery of the cellular bactericidal arsenal to the prey [8]. Killing may be achieved through production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by NADPH oxidase [9]. However, pathogenic microbes develop strategies to avoid PMN killing by suppressing ROS generation [10]. OmpA of E. coli K1 is shown to interact with gp96, a heat shock protein, expressed on the surface of neutrophils for entering and survive in the cells. The interaction of OmpA with gp96 increases the expression of TLR2 and suppresses the expression of TLR4 and CR3 in neutrophils. In addition, OmpA+ E. coli downregulates the expression of gp91phox, Rac1 and Rac2, the components of NADPH oxidase, thereby avoid killing by PMNs. Mutation of three amino acids in the extracellular loops of OmpA and their interaction with PMNs revealed that two regions in loops 1 and 2 are important for interaction. Loop 1 and Loop 2 mutants’ interaction with PMNs significantly increased expression of TLR4 and CR3, thereby increasing the phagocytic ability of PMNs. Of note, depletion of neutrophils or gp96 in newborn mice renders them to be resistant to E. coli K1 infection, indicating that PMNs are initial safe havens for E. coli for survival and multiplication.

The expression of OmpA also influences the entry and survival of E. coli K1 in macrophages. Opsonization with antibody or complement was not required for bacterial entry, indicating that OmpA interaction with a specific receptor is critical for entry into macrophages. Invasion of macrophages was also dependent on microfilament and microtubule condensation [11]. Although macrophages after infection with certain bacteria undergo apoptosis to limit the spreading of the pathogen, many bacterial pathogens developed anti-apoptotic mechanisms to extend the life of these cells for their own advantage. In a similar fashion, E. coli K1 prevents macrophage apoptosis by inducing the expression of anti-apoptotic protein BclXL. Surprisingly, OmpA+ E. coli K1 infected macrophages were resistant to staurosporine-induced apoptosis, indicating that the bacterium takes over the control of macrophage function [12]. An intriguing aspect of E. coli K1 interaction with macrophages is that OmpA was shown to bind the alpha chain of Fcγ receptor I (CD64a) in macrophages for entry and survival (Fig 3A and B). OmpA interaction with CD64a also prevented the association of the γ-chain and induced a tyrosine phosphorylation pattern distinct from Ig2a induced phosphorylation. The OmpA binding to CD64a enhanced the expression of additional CD64 and TLR2 molecules on the surface, whereas it suppressed the expression of TLR4 and CR3. Interestingly, CD64−/− mice were not susceptible to infection due to accelerated clearance of the bacteria as a result of increased CR3 expression (Fig. 3C) [13]. OmpA mediated interaction with macrophages suppressed the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β and other pro-inflammatory cytokines by preventing the phosphorylation of IκB, which in turn responsible for the suppression of NF-κB activation. Macrophages infected with OmpA+ E. coli were unresponsive to LPS induced NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory secretion [14].

Fig. 3. OmpA interaction with CD64 is critical of E. coli K1 survival in macrophages.

(A) RAW 264.7 macrophages were infected with OmpA+ E. coli or OmpA− E. coli for various times, washed, fixed and extracellular and intracellular bacteria were stained with anti-S-fimbria antibody. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophages were transfected with control short hairpin RNA (shRNA), FcγRI or CR3 shRNA and the cells were used for bacterial binding and invasion assays. Both the binding and entry of E. coli were significantly reduced in FcγRI− macrophages. (C) FcγRI−/− infant mice at Day 3 were infected with 103 cfu of E. coli K1, the brains were collected after 72 h, paraffin embedded and tissue sections stained with H and E. Wild type mice showed gliosis, neuronal apoptosis and neutrophil infiltration, whereas FcγRI−/− newborn mice showed no such pathology. Previously published in PLoS Pathogens, DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat. 1001203.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are vital for initiation and modulation of specific immune responses and are the most potent antigen presenting cells (APCs). Immature DCs sample the external environment and capture various antigens including whole bacteria in the periphery and submucosa. After ingestion of bacterial pathogens, DCs migrate to secondary lymphoid tissue where they present processed antigen to stimulate antigen-specific T cells. The activation of DCs relies on the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and abundant surface expression of MHC class II molecules resulting in so-called mature DCs, which are potent stimulators of naive T cells. E. coli K1 has been shown to invade and survive in dendritic cells (DCs), for which the OmpA expression again is critical. OmpA+ E. coli promotes its survival in DCs by suppressing DC maturation markers like CD40, HLA-DR and CD86 [15]. OmpA+ E. coli also induced the interaction of CD47 and thrombospondin-1, which has a negative regulation on the markers for DC maturation [16]. Previous studies have demonstrated that recombinant OmpA from Klebsiella pneumoniae interacts with TLR2. However, this interaction induced the maturation of DCs and production of IL-12, which is distinctly different from OmpA interaction when present in intact E. coli.

E. coli K1 OmpA interaction with brain endothelial cells for invasion

After reaching a certain threshold level of bacteremia, E. coli K1 interacts with the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to invade and enter the central nervous system. Our studies demonstrate that OmpA expression is crucial for E. coli K1 to invade human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMEC), which is an in vitro culture model for the BBB. The studies using OmpA− E. coli K1 showed it invades 25- to 50-fold less than OmpA+ E. coli K1 in HBMEC. Of note, anti-OmpA antibodies that recognize the N-terminal portions of OmpA significantly prevented the invasion of E. coli K1. In agreement with the role of N-terminal regions of OmpA, two synthetic peptides that represent the sequence of Loops 1 and 2 of OmpA significantly inhibited bacterial invasion of HBMEC [17]. Interestingly, one of these peptides had sequence homology to the Loop 2 of OmpA2, encoded by ompA allele 2, found commonly in pathogenic bacteria. In addition, E. coli K1 OmpA was found to interact specifically with GlcNAc1, 4GlcNAc (chitobiose) moieties present on the surface of HBMEC. The chito-oligomers also prevented the onset of meningitis in a rat model of hematogenous meningitis further substantiating the role of these sugars in E. coli K1 pathogenesis [18]. Computer modeling studies demonstrated that the extracellular loops are highly mobile, which upon interaction with chitobiose moieties initially stabilizes the three dimensional structure of OmpA for subsequent interaction with peptide backbone of the receptor [19](Fig. 4). Modeling studies also revealed that the chitobiose binds in two different grooves formed by Loops 1 and 2, and Loop 4 [20].

Fig. 4. Simulation snap shots of OmpA interaction with GlcNAc1, 4 GlcNAc moieties.

Wild-type OmpA binds to two GlcNAc1, 4GlcNAc moieties (chitobiose), one at the tips of loops 1 and 2, and second one near the membrane region at the base of loops 2 and 4. The simulations studies showed that OmpA structure stabilizes by 10 ns with more favorable free energy. In contrast, mutation of three amino acids in loop 2 (aa 61–64) to alanines renders the chitobiose unable to bind and exhibited less favorable energy. Previously published in J. Biol. Chem. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122804.

The receptor for OmpA on HBMEC was identified as Ecgp96, a homolog of gp96 belonging to the Hsp90 heat shock protein family [21,22]. OmpA interaction with Ecgp96 induces a cascade of cellular signals in HBMEC that aid in the successful invasion of the bacterium -[23–33]. It was demonstrated that the purified N-terminal portion of OmpA directly bound HBMEC while a mutant peptide lacking loop regions could not [34]. A recent study also employed E. coli K1 OmpA mutants that completely lacked the loop regions and showed that Loops 1 and 2 were critical for Ecgp96 binding [35]. However, complete deletion of loop regions might severely impair OmpA folding and localization in the outer membrane. A more logical model where selective amino acids in the loop regions were mutated to alanines was used in two different studies recently. One study showed that mutating specific residues in Loops 1, 2 and 4 to alanines significantly prevented bacterial binding and invasion of HBMEC [20]. Although lack of OmpA expression in E. coli K1 modulates the expression of type 1 fimbriae, some of the loop mutations did not affect expression of other surface structures including type 1 fimbriae, suggesting that OmpA interaction with Ecgp96 is truly required for HBMEC invasion. In addition, we have recently demonstrated that Ecgp96 interacts with TLR2 more efficiently upon infection with OmpA+ E. coli, not OmpA− E. coli and that the C-terminal portions of both these molecules are important to induce signaling events in HBMEC for invasion (unpublished data).

OmpA was also shown to be important for E. coli K1 invasion of astrocytes. OmpA expression induced actin re-arrangements in astrocytes. Intra-cerebral injection of E. coli K1 pre-incubated with recombinant OmpA (rOmpA) in C57BL/6 mice had a protective effect while those infected with bacteria alone died within 36 hours. rOmpA pre-incubation also prevented astrocyte activation and neutrophil infiltration in the brain [36].

Pathogenesis of meningitis and necrotizing enterocolitis by Cronobacter sakazakii – twisting the signal by OmpA

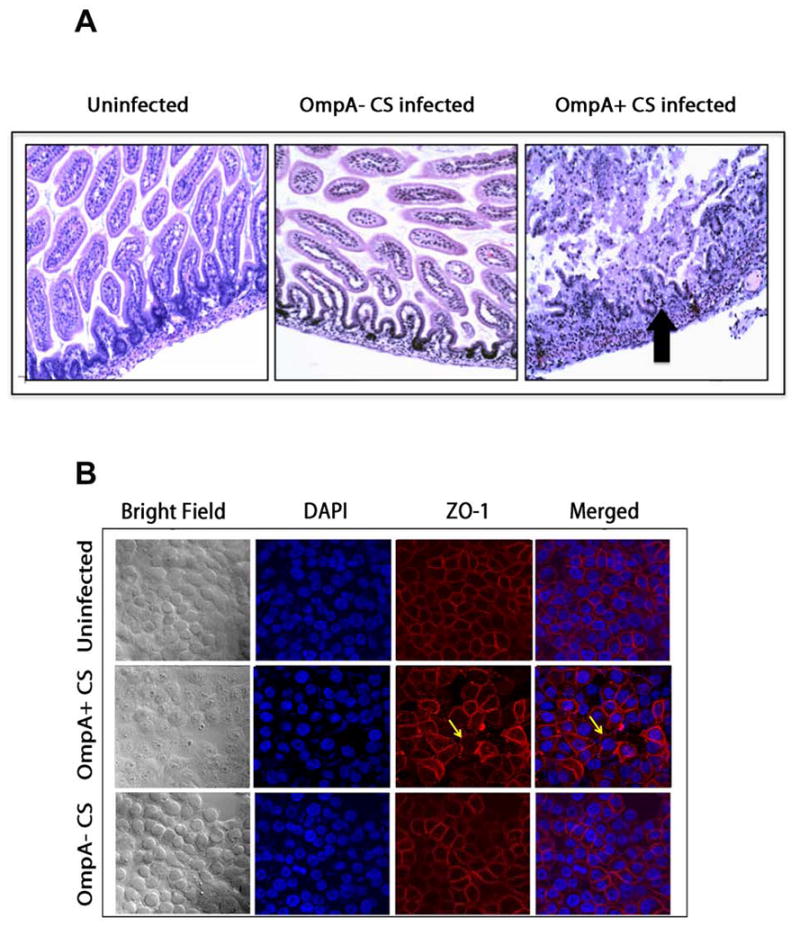

Cronobacter sakazakii (CS), earlier known as Enterobacter sakazakii is an emerging pathogen in neonates that causes necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and meningitis. NEC is an inflammatory intestinal disorder that affects 2%–5% of all premature infants and is associated with high mortality rates. OmpA of CS was required for bacterial invasion of INT407 intestinal cell line. Microtubule and microfilament condensation was also shown to be important for the invasion process [37]. Another porin OmpX along with OmpA was later shown to promote basolateral invasion of CS in epithelial cells [38]. OmpA of CS was also important for invasion of HBMEC but the invasion process required only microtubule condensation and not microfilaments [39]. In agreement with the requirement of OmpA expression, only OmpA+ CS induced meningitis in newborn mouse model of meningitis and was accompanied by neutrophil infiltration, gliosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 5A). CS has also been shown to induce NEC in newborn rat model under hypoxia conditions and in a mouse model. The binding of CS to enterocytes induced apoptosis of the cells by increasing the production of IL-6. Preceding to apoptosis, CS infected enterocytes produced significant quantities of inducible nitric oxide, which in turn is responsible for the disruption of tight junctions (Fig. 5B). Feeding newborn rats with Lactobacillus bulgaricus prior to infection with CS completely prevented the onset of NEC. Subsequent studies have shown that OmpA expression in CS is critical for the binding of the bacterium to enterocytes both in vitro and in animal models.

Fig. 5. OmpA+ CS induces NEC in newborn mice by disrupting the tight junctions.

(A) Newborn mice were infected with OmpA+ CS or OmpA− CS and intestines were processed for H and E staining. Arrow indicates the disruption of villi structure. (B) Confluent monolayers of Caco-2 cells were infected with OmpA+ CS or OmpA− CS for 4 h, washed, fixed and stained with anti-ZO-1 antibody followed by secondary antibody coupled to Cy3. Stained cells were imaged with confocal microscope LSM710. Previously published by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. in J. Immunology, DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100108

CS OmpA binds DC-SIGN (DC specific ICAM non-integrin) for survival in DCs but is not required for DC invasion. OmpA+ CS also induced the anti-inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 to prevent DC maturation. OmpA+ CS could not induce DC maturation and the infected DCs could not present antigens to T-cells despite pretreatment with LPS [40]. Intestinal epithelial cell monolayers pretreated with supernatant from OmpA+ CS/DC culture markedly enhanced membrane permeability and enterocyte apoptosis, whereas OmpA− CS/DC culture supernatant had no effect. Analysis of OmpA+ CS/DC co-culture supernatant revealed significantly greater TGFβ production compared to the levels produced by OmpA− CS infection. TGF-β levels were elevated in the intestinal tissue of mice infected with OmpA+ CS. Co-cultures of CaCo-2 cells, and DCs in a “double layer” model (CaCo-2 cells on the top of the filter and DCs at the bottom in transwell inserts) followed by infection with OmpA+ CS significantly enhanced monolayer leakage by increasing TGFβ production. These studies thus revealed a correlation between DCs and intestinal epithelial cells mediated by TGF-β.

Elevated levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were also observed in the double-layer infection model and suppression of iNOS expression inhibited the CS-induced CaCo-2 cell monolayer permeability even in the presence of DCs or OmpA+ CS/DC supernatant. Blocking TGFβ activity with a neutralizing antibody suppressed iNOS production and prevented apoptosis and monolayer leakage. Depletion of DCs in newborn mice protected against CS-induced NEC while adoptive transfer of DCs rendered the animals susceptible to infection. Therefore, CS interaction with DCs in intestine increases intestinal epithelium damage and the onset of NEC due to increased TGFβ production. In agreement with the role of DCs, infection of newborn mice at Day 3 with CS induced the recruitment of significantly greater number of DCs to the lamina propria in the intestine without change in the recruitment of other immune cells during the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). However, OmpA+ CS only survived in intestine and attached to enterocytes, indicating that CS interaction with DCs is a critical step in the pathogenesis.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis – OprF, the ortholog of OmpA

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is a ubiquitous Gram-negative bacterium that causes ventilator-associated pneumonia, chronic lung infections in CF patients, skin and soft tissue infections of burn victims, and bacteremia and sepsis in cancer patients. Flagella, pili, and lipopolysaccharide initially help PA to bind to the cell surface glycolipid asialo-GM1 during the lung damage. Subsequently, PA uses type III secretion system to inject virulence factors into the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. So far, four effector proteins have been identified in PA: ExoU, ExoS, ExoT, and Exo Y.

OprF of PA is widely considered as an ortholog of OmpA with significant amino acid similarity in their C-terminal domains [41]. It is a general porin that non-specifically allows diffusion of ionic particles and small polar nutrients. Recent advances in OprF porin biology has been reviewed in this series [42]. Being described as an anchoring protein and expressed on the cell surface, OmpA’s role in host-pathogen interaction has been recently getting more attention. OprF has been shown to be responsible for the adhesion to pulmonary epithelial cells, glial cells and Caco-2 cells. OprF also contributes to host pathogenicity in two metazoans models namely, the plant Cichorium intybus and the nematode C. elegans. The H103 strain of PA induced necrosis in the leaves of C. intybus 8 days after inoculation in the middle vein of its leaves while an OprF mutant of the same strain could only induce limited necrosis. PA was also able to kill C. elegans, which required ingestion of the bacteria by the worm and subsequent proliferation in the worm gut.

OprF surprisingly does not express in tandem with other adherence factors during colonization of cystic fibrosis (CF) lung. Pili and flagella expression are completely down regulated during this stage. OprF is essential for microaerobic growth of PA [43]. OprF binding to gamma interferon has been shown to upregulate another adhesin, LecA through quorum sensing. Activation of gamma interferon also increased expression of pyocyanin, which is another quorum sensing related virulence product. Activation of LecA and pyocyanin leads to the disruption of epithelial cell function [44]. OprF expression is also imperative for the formation of anerobic biofilms [45]. OprF mutants are deficient in adherence to animal cells and lack the ability to secrete ExoT and ExoS toxins via the type III secretion system. An OprF mutant was deficient in the production of signal molecules N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone and N-butanoyl-L-homoserine lactone, both of which regulate the timing and production of pyocyanin, elastase, lectin PA-1L and Exotoxin A. OprF is considered as a sensor and modulates quorum sensing to enhance bacterial virulence [46]. A recent study demonstrates the efficacy of two different vector types (Adc7 and Ad5 non- human primate vectors) cloned with oprF gene and their effect on anti-P. aeruginosa systemic and lung immunity in mice. Administration of AdC7OprF to the respiratory tract directly resulted in an increase of OprF-specific IgG and IgA in lung ELF, OprF-specific INF-γ in lung T-cells and OprF-specific IgG in serum compared to immunization with Ad5OprF. Furthermore, challenge with a lethal dose of P. aeruginosa to these animals increased the survival rates [47].

Acinetobacter baumannii – AbOmpA

Acinetobacter baumannii (Ab) is an emerging nosocomial pathogen that causes very severe to fatal pneumonia. The bacterium requires OmpA (AbOmpA) and invades epithelial cells in a zipper-like mechanism by a process with requires both microtubule and microfilament condensation. Presence of OmpA in A. baumannii induced severe lung pathology in a murine model of infection and bacterial burden in the blood while the OmpA− strain could not [48]. AbOmpA was further shown to localize to mitochondria and induce apoptosis in epithelial cells [49]. Transient expression of AbOmpA in epithelial cells led to the localization of the protein in the nucleus and required a novel monopartite nuclear localization signal (NLS). Mutation of NLS led to cytoplasmic localization of AbOmpA [50]. AbOmpA also induced apoptosis of DCs by targeting mitochondria and inducing production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [51].

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli – EHEC-OmpA

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains are responsible for frequent food- and waterborne outbreaks causing non-bloody diarrhea to bloody discharge in humans. A number of diarrheagenic intestinal pathogens including enteropathogenic E. coli, enterohemorragic E. coli and Citrobacter rodentium induce a characteristic adherence pattern upon binding to epithelial cells. An isogenic OmpA mutant of the non-invasive enteric pathogen EHEC showed reduced adherence on cultured HeLa cells, and anti-OmpA serum prevented EHEC binding to HeLa cells [52]. Further studies on EHEC adherence on alfalfa sprouts showed that OmpA was important for binding [53]. EHEC OmpA also induced murine dendritic cells (DCs) to secrete IL-1, IL-10 and IL-2. However, EHEC OmpA could induce DC migration across polarized epithelium [54].

Pasteurella multocida – PmOmpA

P. multocida is a small, Gram-negative, frequently found as a commensal in the upper respiratory tracts of many animals, especially cats and dogs. Humans often infected with P. multocida infection due to animal bite, scratch, or lick. P. multocida OmpA (PmOmpA) binds extracellular matrix proteins like heparin and fibronectin [55]. However, immunization of mice with recombinant PmOmpA did not protect the animal against bacterial challenge in spite of inducing potent serum IgG responses [56].

Klebsiella pneumonia - KpOmpA

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a capsulated Gram-negative pathogen that causes community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia. K. pneumoniae OmpA (KpOmpA) binds and activates DCs and macrophages and triggers cytokine production and DC maturation [57]. However, in airway epithelial cells KpOmpA modulates the inflammatory responses and is responsible for immune evasion. A mutant lacking OmpA triggers higher level of cytokine responses and is attenuated in a pneumonia animal model [58]. OmpA mutants activate IL-8 induction via NF-κB-dependent and p38- and p44/42-dependent pathways. In addition, OmpA mutants of K. pneumonia engage TLR2 and -4 to activate NF-κB. These strategies utilized by KpOmpA may facilitate pathogen survival in the hostile environment of the lung. OmpA gene showed a protective effect against Klebsiella pneumoniae when administered as a DNA vaccine [59].

Salmonella typhimurium – Sal-OmpA

The genus Salmonella contains over 2,000 serotypes and is one of the most important pathogens in the family Enterobacteriaceae, which cause diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramps up to 72 h post-infection. Salmonella typhimurium is one of the common Salmonella serovers that causes Salmonellosis. S. typhimurium OmpA (Sal-OmpA), although does not play a role in bacterial adherence or invasion, has been shown to be a potential vaccine candidate in various studies. Immune response during typhoid fever is predominantly directed against OmpA [60–62]. S. typhimurium OmpA also induces DC maturation via TLR4, p38 and ERK1/2 activation and further enhances Th1 polarization [63]. Sal-OmpA also induces DC maturation and profound activation of MHC II molecules. It also induces a CD4 and CD8 specific response when pulsed along with E7 and PADRE peptides and shows a promising, long term protective anti-tumor effect in mice [64].

Other bacteria and OmpA

Bacteroides vulgatus strains derived from ulcerative colitis (UC) patients revealed the presence of 2 OmpA variants. Tissue adherence of UC- derived strains was stronger than non UC- derived strains. Adherence of DH5-α transformed with OmpA of UC derived strains were also better than non-UC strains [65]. Reimerella anatipestifer OmpA has also been recently shown to be important for binding and invasion of Vero cells in vitro. The bacterium is a major disease causing agent in farm ducks [66].

Conclusion

OmpA has been the subject of many studies to unravel its structural features and porin activity. Its role in the pathogenesis of various bacterial infections is gaining importance lately. Despite its conservation throughout evolution among pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria, OmpA interacts with specific receptors for initiating pathogenesis in some Gram-negative bacterial infections. Computer modeling studies have indicated that OmpA extracellular loops are highly mobile, and thus a variety of three-dimensional structures have been proposed. In reality, the membrane architecture of OmpA in spatial arrangement may depend on the presence of other molecules of that particular pathogen, and thereby enhancing its virulence of certain pathogens. An OmpA homologue, OprF has been emerged as a virulence factor for Pseudomonas aeruginosa for its binding to eukaryotic cells and/or the production of other virulence factors. In addition, OprF is a target for gamma interferon to act as a sensor for quorum sensing leading to activation of virulence factors when in contact with the host. However, due to the emergence of antibiotic resistance strains, the treatment options for reducing Gram-negative bacterial infections will be limited in the future. Therefore, a greater understanding of the pathogenesis mediated by outer membrane proteins, such as OmpA and OprF may lead to development of novel anti-virulence drug targets.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this review was supported by NIH grants AI40567, AI73115, HD41525 and American Heart Association Grants-in Aid (to NVP) and Research Career Development Fellowships by Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

References

- 1.Koebnik R, Locher KP, Van Gelder P. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barriers in a nutshell. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:239–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosetta RN. Insights into the structure and assembly of Escherichia coli outer membrane protein A. FEBS J. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SG, Mahon V, Lambert MA, Fagan RP. A molecular Swiss army knife: OmpA structure, function and expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;273:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiser JN, Gotschlich EC. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) contributes to serum resistance and pathogenicity of Escherichia coli K-1. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2252–2258. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2252-2258.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooijakkers SH, van Strijp JA. Bacterial complement evasion. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasadarao NV, Blom AM, Villoutreix BO, Linsangan LC. A novel interaction of outer membrane protein A with C4b binding protein mediates serum resistance of Escherichia coli K1. J Immunol. 2002;169:6352–6360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wooster DG, Maruvada R, Blom AM, Prasadarao NV. Logarithmic phase Escherichia coli K1 efficiently avoids serum killing by promoting C4bp-mediated C3b and C4b degradation. Immunology. 2006;117:482–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood. 1998;92:3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer-Scholl A, Averhoff P, Zychlinsky A. How do neutrophils and pathogens interact? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sukumaran SK, Shimada H, Prasadarao NV. Entry and intracellular replication of Escherichia coli K1 in macrophages require expression of outer membrane protein A. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5951–5961. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5951-5961.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sukumaran SK, Selvaraj SK, Prasadarao NV. Inhibition of apoptosis by Escherichia coli K1 is accompanied by increased expression of BclXL and blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release in macrophages. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6012–6022. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6012-6022.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittal R, Sukumaran SK, Selvaraj SK, Wooster DG, Babu MM, Schreiber AD, Verbeek JS, Prasadarao NV. Fcgamma receptor I alpha chain (CD64) expression in macrophages is critical for the onset of meningitis by Escherichia coli K1. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001203. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvaraj SK, Prasadarao NV. Escherichia coli K1 inhibits proinflammatory cytokine induction in monocytes by preventing NF-kappaB activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:544–554. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mittal R, Prasadarao NV. Outer membrane protein A expression in Escherichia coli K1 is required to prevent the maturation of myeloid dendritic cells and the induction of IL-10 and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008;181:2672–2682. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittal R, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Prasadarao NV. Escherichia coli K1 promotes the ligation of CD47 with thrombospondin-1 to prevent the maturation of dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of neonatal meningitis. J Immunol. 185:2998–3006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasadarao NV, Wass CA, Weiser JN, Stins MF, Huang SH, Kim KS. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli contributes to invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:146–153. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.146-153.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasadarao NV, Wass CA, Kim KS. Endothelial cell GlcNAc beta 1–4GlcNAc epitopes for outer membrane protein A enhance traversal of Escherichia coli across the blood-brain barrier. Infect Immun. 1996;64:154–160. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.154-160.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Datta D, Vaidehi N, Floriano WB, Kim KS, Prasadarao NV, Goddard WA., 3rd Interaction of E. coli outer-membrane protein A with sugars on the receptors of the brain microvascular endothelial cells. Proteins. 2003;50:213–221. doi: 10.1002/prot.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascal TA, Abrol R, Mittal R, Wang Y, Prasadarao NV, Goddard WA., 3rd Experimental validation of the predicted binding site of Escherichia coli K1 outer membrane protein A to human brain microvascular endothelial cells: identification of critical mutations that prevent E. coli meningitis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37753–37761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prasadarao NV. Identification of Escherichia coli outer membrane protein A receptor on human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4556–4563. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4556-4563.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasadarao NV, Srivastava PK, Rudrabhatla RS, Kim KS, Huang SH, Sukumaran SK. Cloning and expression of the Escherichia coli K1 outer membrane protein A receptor, a gp96 homologue. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1680–1688. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.1680-1688.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sukumaran SK, Prasadarao NV. Escherichia coli K1 invasion increases human brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayer permeability by disassembling vascular-endothelial cadherins at tight junctions. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1295–1309. doi: 10.1086/379042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy MA, Prasadarao NV, Wass CA, Kim KS. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and interaction with focal adhesion kinase in Escherichia coli K1 invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36769–36774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy MA, Wass CA, Kim KS, Schlaepfer DD, Prasadarao NV. Involvement of focal adhesion kinase in Escherichia coli invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6423–6430. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6423-6430.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sukumaran SK, Quon MJ, Prasadarao NV. Escherichia coli K1 internalization via caveolae requires caveolin-1 and protein kinase Calpha interaction in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50716–50724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukumaran SK, Prasadarao NV. Regulation of protein kinase C in Escherichia coli K1 invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12253–12262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudrabhatla RS, Sukumaran SK, Bokoch GM, Prasadarao NV. Modulation of myosin light-chain phosphorylation by p21-activated kinase 1 in Escherichia coli invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2787–2797. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2787-2797.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudrabhatla RS, Selvaraj SK, Prasadarao NV. Role of Rac1 in Escherichia coli K1 invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selvaraj SK, Periandythevar P, Prasadarao NV. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli K1 selectively enhances the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maruvada R, Argon Y, Prasadarao NV. Escherichia coli interaction with human brain microvascular endothelial cells induces signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 association with the C-terminal domain of Ec-gp96, the outer membrane protein A receptor for invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2326–2338. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittal R, Prasadarao NV. Nitric oxide/cGMP signalling induces Escherichia coli K1 receptor expression and modulates the permeability in human brain endothelial cell monolayers during invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:67–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittal R, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Goth KA, Prasadarao NV. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide controls pathogen load and brain damage by enhancing phagocytosis of Escherichia coli K1 in neonatal meningitis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1292–1305. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin S, Lu G, Cai M, Kim KS. Escherichia coli outer membrane protein A adheres to human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:1199–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maruvada R, Kim KS. Extracellular loops of the Eschericia coli outer membrane protein A contribute to the pathogenesis of meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:131–140. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu HH, Yang YY, Hsieh WS, Lee CH, Leu SJ, Chen MR. OmpA is the critical component for Escherichia coli invasion-induced astrocyte activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:677–690. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a77d1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan Nair MK, Venkitanarayanan K. Role of bacterial OmpA and host cytoskeleton in the invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells by Enterobacter sakazakii. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:664–669. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181587864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim K, Kim KP, Choi J, Lim JA, Lee J, Hwang S, Ryu S. Outer membrane proteins A (OmpA) and X (OmpX) are essential for basolateral invasion of Cronobacter sakazakii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5188–5198. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02498-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singamsetty VK, Wang Y, Shimada H, Prasadarao NV. Outer membrane protein A expression in Enterobacter sakazakii is required to induce microtubule condensation in human brain microvascular endothelial cells for invasion. Microb Pathog. 2008;45:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mittal R, Bulgheresi S, Emami C, Prasadarao NV. Enterobacter sakazakii targets DC-SIGN to induce immunosuppressive responses in dendritic cells by modulating MAPKs. J Immunol. 2009;183:6588–6599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brinkman FS, Bains M, Hancock RE. The amino terminus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane protein OprF forms channels in lipid bilayer membranes: correlation with a three-dimensional model. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5251–5255. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5251-5255.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugawara E, Nagano K, Nikaido H. Alternative Folding Pathways of the Major Porin OprF of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEBS J. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hogardt M, Heesemann J. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during persistence in the cystic fibrosis lung. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu L, Estrada O, Zaborina O, Bains M, Shen L, Kohler JE, Patel N, Musch MW, Chang EB, Fu YX, Jacobs MA, Nishimura MI, Hancock RE, Turner JR, Alverdy JC. Recognition of host immune activation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science. 2005;309:774–777. doi: 10.1126/science.1112422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hassett DJ, Cuppoletti J, Trapnell B, Lymar SV, Rowe JJ, Yoon SS, Hilliard GM, Parvatiyar K, Kamani MC, Wozniak DJ, Hwang SH, McDermott TR, Ochsner UA. Anaerobic metabolism and quorum sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in chronically infected cystic fibrosis airways: rethinking antibiotic treatment strategies and drug targets. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1425–1443. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fito-Boncompte L, Chapalain A, Bouffartigues E, Chaker H, Lesouhaitier O, Gicquel G, Bazire A, Madi A, Connil N, Veron W, Taupin L, Toussaint B, Cornelis P, Wei Q, Shioya K, Deziel E, Feuilloley MG, Orange N, Dufour A, Chevalier S. Full virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires OprF. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1176–1186. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00850-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krause A, Whu WZ, Xu Y, Joh J, Crystal RG, Worgall S. Protective anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa humoral and cellular mucosal immunity by AdC7-mediated expression of the P. aeruginosa protein OprF. Vaccine. 2011;29:2131–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi CH, Lee JS, Lee YC, Park TI, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii invades epithelial cells and outer membrane protein A mediates interactions with epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi CH, Lee EY, Lee YC, Park TI, Kim HJ, Hyun SH, Kim SA, Lee SK, Lee JC. Outer membrane protein 38 of Acinetobacter baumannii localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1127–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi CH, Hyun SH, Lee JY, Lee JS, Lee YS, Kim SA, Chae JP, Yoo SM, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A targets the nucleus and induces cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:309–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee JS, Choi CH, Kim JW, Lee JC. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A induces dendritic cell death through mitochondrial targeting. J Microbiol. 2010;48:387–392. doi: 10.1007/s12275-010-0155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torres AG, Kaper JB. Multiple elements controlling adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4985–4995. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4985-4995.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres AG, Jeter C, Langley W, Matthysse AG. Differential binding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to alfalfa, human epithelial cells, and plastic is mediated by a variety of surface structures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8008–8015. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8008-8015.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torres AG, Li Y, Tutt CB, Xin L, Eaves-Pyles T, Soong L. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli O157:H7 stimulates dendritic cell activation. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2676–2685. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2676-2685.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dabo SM, Confer AW, Quijano-Blas RA. Molecular and immunological characterization of Pasteurella multocida serotype A:3 OmpA: evidence of its role in P. multocida interaction with extracellular matrix molecules. Microb Pathog. 2003;35:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(03)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dabo SM, Confer A, Montelongo M, York P, Wyckoff JH., 3rd Vaccination with Pasteurella multocida recombinant OmpA induces strong but non-protective and deleterious Th2-type immune response in mice. Vaccine. 2008;26:4345–4351. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeannin P, Magistrelli G, Goetsch L, Haeuw JF, Thieblemont N, Bonnefoy JY, Delneste Y. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA): a new pathogen-associated molecular pattern that interacts with antigen presenting cells-impact on vaccine strategies. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 4):A23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00383-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.March C, Moranta D, Regueiro V, Llobet E, Tomas A, Garmendia J, Bengoechea JA. Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane protein A is required to prevent the activation of airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9956–9967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.181008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurupati P, Ramachandran NP, Poh CL. Protective efficacy of DNA vaccines encoding outer membrane protein A and OmpK36 of Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 18:82–88. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00275-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonzalez CR, Isibasi A, Ortiz-Navarrete V, Paniagua J, Garcia JA, Blanco F, Kumate J. Lymphocytic proliferative response to outer-membrane proteins isolated from Salmonella. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37:793–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Udhayakumar V, Muthukkaruppan VR. Protective immunity induced by outer membrane proteins of Salmonella typhimurium in mice. Infect Immun. 1987;55:816–821. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.816-821.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh SP, Williams YU, Miller S, Nikaido H. The C-terminal domain of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium OmpA is an immunodominant antigen in mice but appears to be only partially exposed on the bacterial cell surface. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3937–3946. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3937-3946.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee JS, Jung ID, Lee CM, Park JW, Chun SH, Jeong SK, Ha TK, Shin YK, Kim DJ, Park YM. Outer membrane protein a of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium activates dendritic cells and enhances Th1 polarization. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jang MJ, Kim JE, Chung YH, Lee WB, Shin YK, Lee JS, Kim D, Park YM. Dendritic cells stimulated with outer membrane protein A (OmpA) of Salmonella typhimurium generate effective anti-tumor immunity. Vaccine. 2011;29:2400–2410. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sato K, Kumita W, Ode T, Ichinose S, Ando A, Fujiyama Y, Chida T, Okamura N. OmpA variants affecting the adherence of ulcerative colitis-derived Bacteroides vulgatus. J Med Dent Sci. 2010;57:55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu Q, Han X, Zhou X, Ding C, Zhu Y, Yu S. OmpA is a virulence factor of Riemerella anatipestifer. Vet Microbiol. 2011;150:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]