Abstract

The major mode of HIV/AIDS transmission in China is now heterosexual activities, but risk for HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) may differ among different strata of female sex workers (FSWs). Respondent-driven sampling was used to recruit 320 FSWs in Guangdong Province, China. The respondents were interviewed using a structured questionnaire, and tested for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and Chlamydia. The street-based FSWs had lower education levels, a higher proportion supporting their families, charged less for their services, and had engaged in commercial sex for a longer period of time than establishment-based FSWs. The proportion consistently using condoms with clients and with regular non-paying partners was also lower. The prevalence of syphilis, gonorrhea, and Chlamydia was higher among street-based sex workers. Being a street-based sex worker, having regular non-paying sex partners, and having non-regular non-paying partners were independent risk factors for inconsistent condom. Street-based FSWs had more risk behaviors than establishment-based FSWs, and should therefore be specifically targeted for HIV as well as STD intervention programs.

Keywords: Behavior, HIV/AIDS, HIV, STD, Female sex workers

Introduction

Guangdong Province is situated in the southern part of the Chinese mainland and adjacent to Hong Kong. It was the first province in China to adopt the economic reform and open-door policy in 1978. Guangdong Province is amongst the six provinces in China reporting the highest numbers of HIV/AIDS cases. The epidemic of HIV/AIDS was largely confined to injection drug users (IDUs) in Guangdong Province before 2007 [1]. However, heterosexual transmission has increasingly been the source of infections in recent years. In Guangdong Province in 2009, the most common transmission mode was heterosexual contact, and accounted for 52.4% of reported HIV/AIDS cases [2]. The results from the HIV sentinel surveillance among sexual transmitted disease (STD) clinic patients in Guangdong Province also suggested increasing HIV transmission through heterosexual contact [3]. The risk behaviors among female sex workers (FSWs) are likely to determine how fast the HIV epidemic will spread to the general population. Understanding their risk behaviors and associated factors are important for predicting the future of the HIV epidemic in China.

Although the major risk practices identified among FSWs are injection drug use and not using condoms [4], previous studies have shown that HIV risk behaviors vary among different kinds of sex workers. The STD prevalence survey of FSWs conducted in Surabaya, Indonesia in 1993 indicated that sex workers in brothels, streets, and nightclubs used condoms infrequently (14, 20, and 25%, respectively), whereas sex workers in massage parlors, barber shops, and on-call were about three to five times more likely to have used condoms than those in nightclubs (adjusted ORs 3.5, 4.9, and 4.2, respectively) during their last paid sexual encounter [5]. Abellanosa et al. [6] reported that unregistered FSWs were at a higher risk for HIV infection than registered FSWs in the Philippines. Pickering et al. classified FSWs in a trading town on the trans-Africa highway into three classes, based on amount charged and the residence of clients [7, 8]. A study of FSWs conducted in Bali, Indonesia in 1992–1993 classified FSWs into four groups: (1) women working in low-cost complexes supervised by a pimp in the Denpasar area; (2) mid-priced women who rented rooms within family complexes or bungalows; (3) women working in high-cost houses in and around Denpasar; and (4) independent workers at Kuta tourist resorts [9]. A study conducted in Guyana identified two groups of FSWs. One was streetwalkers who belonged to the “lower” socio-economic stratum, and the other was sex workers in bars and hotels who belonged to a “higher” stratum [10]. However, Tran et al. [11] reported no significant differences in condom use between “middle-” and “low-class” FSWs in Vietnam.

According to the formative study preceding this quantitative study, two main types of FSWs were identified in Guangdong Province, establishment-based and street-based. Establishment-based FSWs work in bars, clubs, massage parlors, karaoke bars, and hotels, and provide sex services on a part-time basis to supplement their regular salaries. Street-based FSWs meet their clients on the streets or other places and have no other occupation.

Since 1997, in Guangdong Province, three HIV sentinel surveillance sites were set up in re-education centers. The results from the sentinel surveillance showed that HIV prevalence was steady, varying from 0.0 to 2.27%, and was correlated with injection drug use between 1997 and 2008. Three more behavioral surveillance sites for community-based FSWs were set up in 2005. The HIV prevalence from the surveillance sites for community-based FSWs was usually 0.0% between 2005 and 2008, except for 0.5% in Zhuhai and 0.24% in Shenzhen in 2006 [3]. Due to the lack of visibility of street-based sex workers, most behavioral surveillance among FSWs in Guangdong Province sample sex workers in establishments and miss street-based sex workers. A representative sample of community-based FSWs was needed to understand their HIV/STI prevalence and risk behaviors. Additionally, comparison of the risk behaviors between the establishment- and the street-based sex workers not only expanded upon by the results of the current behavioral surveillance, but can serve as guidance for future intervention programs targeting FSWs.

Due to their illegal status and the hidden nature of the FSWs, a special method was needed to obtain a more representative sample for the population; namely, respondent-driven sampling (RDS), which has been used to recruit hidden populations such as IDUs and men who have sex with men (MSM). It is a variant of chain-referral sampling that offers an incentive for being interviewed and an additional incentive for recruiting peers. It has been reported to reduce the biases generally associated with chain-referral methods [12]. It also provides estimates of the variability of indicators and strategies to compute standard errors for population estimates [13, 14]. The Vietnamese Ministry of Health conducted a survey using RDS to assess HIV prevalence, risk factors, and service utilization among FSWs in 2004. The program showed that RDS could include the less visible FSWs and may provide better estimates for the population [15].

This study used RDS to recruit FSWs in the community, and to estimate the risk behaviors and STD prevalence among both establishment- and street-based FSWs, and their correlates associated with risk behaviors. Previous surveillance did not use RDS; therefore, for comparability between the venue-based and community-based samples in our study, we felt that it was advisable to use the same recruitment strategy.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The source population was FSWs who lived or worked in the study county. FSWs were defined as those who had provided sex for cash or other goods such as drugs in the past 6 months. It excluded those who exchanged sex for gifts or other material rewards from their steady non-commercial partners. Only FSWs 18 years or older were included.

This cross-sectional study was carried out from August 2006 to January 2007. RDS was used to recruit participants into the study. Four “seeds” were recruited, including one street-based sex worker and three establishment-based sex workers. After the seeds completed the study, each of them was given three coupons to recruit any type of FSW into the study. All new recruits were offered a dual incentive: (1) to participate; and (2) to recruit up to three of their peers into the study. The participants were offered $20 U.S. compensation for their time and transportation for the interview, examination, and sample donation. A second incentive of $6 U.S. was offered for each referral who successfully completed the interview. Referral was terminated when equilibrium with respect to key variables was reached. Overall, the equilibriums with respect to social and demographic characteristics, including education level, age group, having been married, currently supporting family, and work venue were obtained after two to ten waves. In total, 864 recruitment coupons were distributed, of which 316 (36.6%) were returned, indicating a response rate of 36.6%.

An office in the local Dermatology and STD Hospital was the setting for the interviews. The eligible participants underwent a face-to-face interview with specially trained female counselors, using a standardized questionnaire to collect information on HIV infection risk behaviors and potential correlates. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part included questions about their knowledge and attitudes about HIV/AIDS, and some basic demographic information. The second part queried about their sexual and/or drug use-related behaviors. For the second part, the participants had the option of being interviewed face-to-face by the interviewer or using a CD player with pre-recorded questions and an answer sheet [16]. Twenty participants opted to use the CD player, and all others opted for face-to-face interviews. The entire interview lasted 30–60 min.

After each interview, the participant received a free examination by a female gynecologist at the outpatient clinic of the hospital. A cervical swab was collected for testing for gonorrhea and Chlamydia. A 5-ml blood sample was also collected for testing for HIV and syphilis.

Both the interviews and testing were anonymous. No identifying information was collected, although the specimens were linked with the interview data through study numbers.

The study was approved by the UCLA IRB (#G04-08-030) and by the Guangdong Province CDC IRB in 2006.

Testing Methods

Blood samples were collected for HIV and syphilis testing. Serum samples were screened for antibodies to T. pallidum by the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test (Rongsheng Bio-technical Company, Shanghai, China). Positive specimens were confirmed by T. pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA). Syphilis infection was defined as being positive for both RPR and TPHA, and HIV antibody testing was done by ELISA (Gibiai Biotechnical Co., Beijing, China). If the test was positive, two further assays (the original assay plus a different assay) were conducted in parallel. If both were negative, the result was recorded as HIV-negative. If both were positive or there was discordance in the results, the specimen was sent to a confirmatory laboratory for western blot testing.

Cervical swabs were rolled in a culture plate and incubated in a CO2 jar at 37°C for 24 h. The Thayer–Martin selective culture media was used for culturing N. gonorrhea. For confirmatory testing, the oxidase and sugar fermentation tests were performed. Typical colonies of oxidase-positive, gram-negative diplococci on T–M culture media with a positive glucose fermentation test were used as criteria for identification of N. gonorrhea. Chlamydia was diagnosed by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing.

All testing was conducted in the laboratory of the Zhaoqing Dermatology and STD Hospital. HIV-positive blood samples were also sent to the HIV Confirmatory Center of the Guangdong CDC for HIV antibody testing (ELISA assay, Organon Teknika, Netherlands).

Data Analysis

The data were entered using Epidata. The data were double-entered by two researchers independently, and were checked to assure accuracy and completeness.

The participants were categorized as either establishment- or street-based FSWs according to their work venues (the main places where they solicited or met their clients, as indicated during their interviews; not through the location of the original seed). The establishment-based sex workers included those who meet their clients in karaoke bars, night clubs, bars, massage bars, hair/beauty salons, and hotels (guesthouses); we also classified two participants who usually met their clients through “mummies'” (pimps) into this category, since the mummies (pimps) are usually based in such establishments. Street-based sex workers included those who meet the clients in the streets, the participants' own rented apartments, parks, malls, and/or construction sites.

Inconsistent condom use was treated as the dependent variable. It was defined as not using condoms 100% of the time for all sex acts during the past week, including any type of intercourse (oral, vaginal, or anal) with any type of partner (clients, regular non-paying partners, or non-regular non-paying partners). Consistent condom use was defined as using condoms 100% of the time for all sex acts during the past week. Types of sex partners were classified into three categories: clients who paid for sex, regular non-paying partners such as spouses and lovers who had a steady relationship with the participants, and non-regular non-paying partners who were non-paying casual partners.

Prevalence of risk behaviors and potential correlates were described by measuring frequency distribution. The characteristics and related behaviors between establishment- and street-based FSWs were compared using both the specific estimated prevalence (EPP) adjusted for the RDS sampling, using RDSAT, and the crude specific prevalence (SPP). Comparisons between the two groups were performed using the χ2 or Fisher's exact tests for crude proportions and t-test for continuous variables.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the associations of independent variables with the outcome variable (inconsistent condom use), simultaneously adjusting for potential confounders, using SAS. The individualized weights generated for the dependent variables, using RSDAT, were used to weight the data set for multivariate analysis [17]. Variables were selected into the multivariate model based on prior knowledge of the relationship between them and inconsistent condom use. If there was no prior knowledge, variables were selected depending on how much their presence/absence affected the confidence intervals of other variables in the model. The cut-off level of change of the confidence intervals of these variables of interest was predefined as 10%.

Results

Introduction of Recruitment Process (RDS)

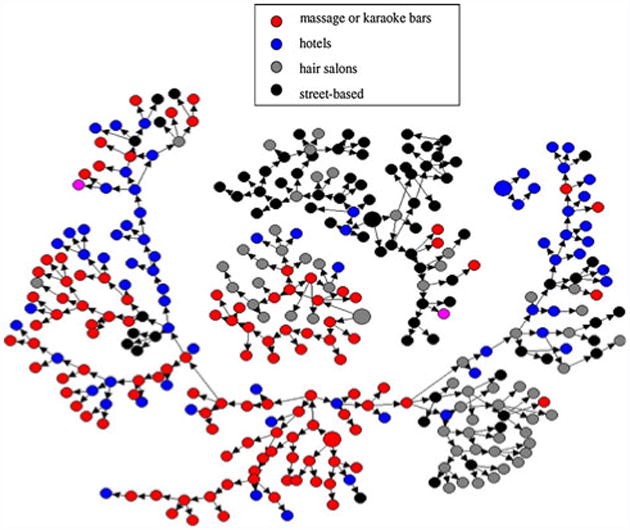

A total of 320 participants, including the four seeds, were recruited into the study. The respondence rate was 36.6%. The street-based seed sex worker recruited 65 participants, and the three establishment-based seed sex workers recruited 209, 3, and 39 participants. The longest recruitment tree had 16 recruitment waves. Figure 1 depicts the recruitment tree by venues of the participants.

Fig. 1. Recruitment tree by work venus of FSWs.

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 320 participants, 241 (75.3%) were establishment-based sex workers and 77 (24.1%) were street-based sex workers (two of the participants had unknown work venues). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants. Establishment-based sex workers had higher education levels than the street-based sex workers, and a higher proportion of the street-based sex workers were currently supporting their families than the establishment-based sex workers. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the establishment- and street-based female commercial sex workers.

| Characteristics | EPP (95% CI) (%) | SPP | χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment-based FSWs (N = 241) | Street-based FSWs (N = 77) | Establishment-based FSWs (N = 241) | Street-based FSWs (N = 77) | ||

| Age group | |||||

| 18–29 years | 67.9 (57.7–78.0) | 67.6 (47.2–84.3) | 71.8 | 70.1 | 0.078 |

| 30–48 years | 32.1 (22.0–42.3) | 32.4 (15.7–52.8) | 28.2 | 29.9 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Han ethnicity | 97.3 (95.0–99.1) | 96.4 (91.9–99.6) | 97.1 | 94.8 | 0.917 |

| Minorities | 2.7 (0.9–5.0) | 3.6 (0.4–8.1) | 2.9 | 5.2 | |

| Education* | |||||

| Illiterate | 4.3 (1.3–7.3) | 8.3 (0.0–18.1) | 2.5 | 5.2 | 10.438 |

| Primary school (1–6 years) | 34.0 (27.0–42.3) | 40.2 (27.5–57.6) | 26.3 | 29.9 | |

| Middle school (7–9 years) | 51.2 (42.5–60.0) | 50.0 (32.0–64.6) | 57.5 | 63.6 | |

| High school (10–12 years) | 9.9 (5.4–14.3) | 1.5 (0.0–5.6) | 12.5 | 1.3 | |

| Higher (over 12 years) | 0.5 (0.0–1.4) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.3 | 0.0 | |

| Registered residency | |||||

| Guangdong | 8.6 (3.2–15.1) | 2.9 (0.0–8.6) | 7.9 | 3.9 | 1.441 |

| Not Guangdong | 91.4 (84.9–96.8) | 97.1 (91.4–100.0) | 92.1 | 96.1 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Ever married | 59.1 (50.1–67.4) | 60.3 (44.7–77.7) | 52.5 | 48.1 | 0.462 |

| Never married | 40.9 (32.6–49.9) | 39.7 (22.3–55.3) | 47.5 | 51.9 | |

| Cohabitation | |||||

| Living with partner | 41.1 (32.6–49.0) | 33.7 (24.2–44.8) | 42.9 | 40.3 | 0.168 |

| Not living with partner | 58.9 (51.0–67.4) | 67.3 (55.2–75.8) | 57.1 | 59.7 | |

| Supporting family** | |||||

| Supporting family | 82.6 (77.2–87.7) | 93.2 (86.5–99.0) | 82.6 | 93.5 | 5.539 |

| Not supporting family | 17.4 (12.3–22.8) | 6.8 (1.0–13.5) | 17.4 | 6.5 | |

| Sources of income other than commercial sex | |||||

| Other sources of income | 54.5 (46.3–62.5) | 51.1 (34.4–66.8) | 46.4 | 45.5 | 0.023 |

| No other source | 45.5 (37.5–53.7) | 48.9 (33.2–65.6) | 53.6 | 54.5 | |

EPP estimated population proportion, SPP sample population proportion

P = 0.03;

P = 0.02

Health-Related Behaviors Among the FSWs

As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences between establishment- and street-based sex workers (P > 0.05) regarding reported genital discharge, genital ulcer/sores, or diagnosed STDs. Compared with the street-based FSWs, a higher proportion of the establishment-based sex workers had been tested for HIV (25.0% vs. 2.3%, P < 0.05). None of the FSWs had injected drugs, although 9.0% of the establishment- and 5.0% of the street-based sex workers had used “ecstasy” (P > 0.05).

Table 2. Health-related behaviors and sexual behaviors among establishment- and street-based FSWs.

| EPP (95% CI) (%) | SPP | χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment-based FSW (N = 241) | Street-based FSW (N = 77) | Establishment-based FSW (N = 241) | Street-based FSW (N = 77) | ||

| Had genital discharge within the past 12 months | 44.0 (34.5–53.5) | 45 (30.9–59.3) | 52.7 | 52.0 | 0.015 |

| Had genital ulcer/sore(s) within the past 12 months | 5.8 (2.4–9.3) | 2.1 (0.0–6.5) | 5.9 | 1.3 | 2.677 |

| Diagnosed with a STD within the past 12 months | 3.4 (1.0–6.3) | 6.5 (0.8–13.4) | 3.6 | 5.5 | 0.474 |

| Ever tested for HIV* | 25.0 (16.2–35.3) | 2.3 (0.0–7.4) | 27.1 | 1.3 | 23.101 |

| Ecstasy use | 9.0 (5.1–13.5) | 5.0 (1.4–10.9) | 10.4 | 7.8 | 0.455 |

| Age at sexual debut | 19.3a | 18.8a | 1.97b | ||

| Age at first commercial sex | 24.6a | 25.2a | 0.70b | ||

| Duration of being a CSW (months)* | 16.0 | 36.0 | 4.8129c | ||

| Charge for commercial sex (RMB/Yuan)* | 200.0 | 100.0 | 7.7740c | ||

| Numbers of sex partners | |||||

| Number of clients in the past week** | 4 | 6 | 1.9001c | ||

| 0–6 | 72.4 (65.3–78.8) | 67.2 (55.5–78.2) | 66.8 | 61.0 | 8.4466 |

| 7–13 | 22.4 (17.2–28.2) | 32.8 (21.8–44.5) | 26.6 | 39.0 | |

| 14–30 | 5.2 (2.0–9.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 6.6 | 0.0 | |

| Number of regular non–paying sex partners in the past week | |||||

| 0 | 52.9 (45.6–60.2) | 56.0 (42.0–68.1) | 53.8 | 46.8 | 1.1435 |

| 1–2 | 47.1 (39.8–54.4) | 44.0 (31.9–58.0) | 46.2 | 53.2 | |

| Number of non-regular non-paying partners in the past week | |||||

| 0 | 89.7 (84.6–94.7) | 82.9 (65.9–94.9) | 92.5 | 89.6 | 0.6465 |

| 1–3 | 10.3 (5.3–15.4) | 17.1 (5.1–34.1) | 7.5 | 10.4 | |

EPP estimated population proportion, SPP sample population proportion

P < 0.0001;

P = 0.015

Mean and median

t value and P value for the t-test

z value and P value for Wilcoxon test

Sexual Behaviors Among FSWs

Table 2 indicates that the ages at sexual debut and at first commercial sex were not significantly different between the establishment- and street-based sex workers. The median duration of being a sex worker was 16 months among establishment-based sex workers, and 36 months among street-based sex workers (P < 0.05). The median charge for commercial sex was 200 RMB Yuan (approximately $US 30) among establishment-based sex workers, and 100 RMB Yuan (approximately $US 15) among street-based sex workers (P < 0.05).

The medians for numbers of clients during the past week among the establishment- and street-based FSWs were four and six, respectively, which was not significant (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences in the numbers of regular non-paying partners and non-regular non-paying partners between the two groups.

Condom Use with Sex Partners

Table 3 presents condom use with clients and non-paying partners. The proportions inconsistently using condoms with clients for any type of intercourse were significantly higher among the street-based sex workers (P < 0.05). The overall proportions of inconsistent condom use with clients in the past week were 72.2% (ranging 59.0–83.7%) among street-based sex workers and 30.9% (23.3–38.3%) among establishment-based sex workers. Furthermore, the street-based sex workers were more likely to agree to sex without condoms when offered more money. A lower proportion had tried to persuade their clients to use condoms, and they had less success with those negotiations.

Table 3. Condom use with sex partners among establishment- and street-based FSWs.

| EPP (95% CI) (%) | SPP | χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment-based FSWs | Street-based FSWs | Establishment-based FSWs | Street-based FSWs | ||

| Condom use with clients during last encounter* | |||||

| Yes | 93.9 (90.5–97.2) | 92.8 (87.1–97.5) | 95.0 (227/239) | 88.3 (68/77) | 4.173 |

| No | 6.1 (2.8–9.5) | 7.2 (2.5–12.9) | 5.0 (12/239) | 11.7 (9/77) | |

| Frequency of condom use when having vaginal sex with clients in the past week** | |||||

| Consistent condom use | 74.9 (67.5–82.3) | 28.2 (16.8–41.4) | 80.2 (190/237) | 23.4 (18/77) | 83.826 |

| Inconsistent condom use | 25.1 (17.7–32.5) | 71.8 (58.6–83.2) | 19.8 (47/237) | 76.6 (59/77) | |

| Frequency of condom use when having oral sex with clients in the past week** | |||||

| Consistent condom use | 50.0 (34.7–67.9) | 0.0 (–) | 53.4 (39/73) | 6.3 (2/32) | 20.803 |

| Inconsistent condom use | 50.0 (32.1–65.3) | 100.0 (–) | 46.6 (34/73) | 93.8 (30/32) | |

| Frequency of condom use when having anal sex with clients in the past week* | |||||

| Consistent condom use | 0.0 (–) | 50.6 (–) | 57.1 (4/7) | 0.0 (0/8) | 6.234 |

| Inconsistent condom use | 100.0 (–) | 49.4 (–) | 42.9 (3/7) | 100.0 (8/8) | |

| No condom use if offered more money** | |||||

| Might agree | 25.5 (17.6–34.2) | 79.2 (65.5–90.2) | 21.2 (49/231) | 82.9 (63/76) | 93.894 |

| Would not agree | 74.5 (65.8–82.4) | 20.8 (9.8–34.5) | 78.8 (182/231) | 17.1 (13/76) | |

| Frequency of success when trying to persuade clients to use condoms** | |||||

| Less than 100% | 54.8 (45.7–62.7) | 75.6 (62.9–86.2) | 55.8 (130/233) | 77.6 (59/76) | 24.187 |

| Almost 100% | 31.7 (25.2–39.3) | 3.1 (0.4–7.0) | 33.9 (79/233) | 5.3 (4/76) | |

| Never persuaded | 13.5 (7.9–20.5) | 21.4 (11.2–33.1) | 10.3 (24/233) | 17.1 (13/76) | |

| Condom use last time having sex with regular non-paying partners* | |||||

| Yes | 32.7 (21.7–37.6) | 26.6 (17.3–39.8) | 42.3 (69/163) | 27.9 (17/61) | 3.925 |

| No | 67.3 (62.4–78.3) | 73.4 (60.2–82.7) | 57.7 (94/163) | 72.1 (44/61) | |

| Condom use in past week when having sex with regular non-paying partners* | |||||

| Consistent condom use | 19.4 (9.8–24.1) | 16.7 (0.0–39.2) | 21.8 (27/124) | 4.8 (2/42) | 6.298 |

| Inconsistent condom use | 80.6 (75.9–90.2) | 83.3 (60.8–100.0) | 78.2 (97/124) | 95.2 (40/42) | |

| Condom use when last having sex with non-regular non-paying partners | |||||

| Yes | 100.0 (–) | 58.6 (–) | 70.0 (14/20) | 75.0 (6/8) | 0.070 |

| No | 0.0 (–) | 41.4 (–) | 30.0 (6/20) | 25.0 (2/8) | |

| Frequency of condom use in past week when having sex with non-regular non-paying partners | |||||

| Consistent condom use | 100.0 (–) | 0.0 (–) | 4.7 | 6.5 | 0.240 |

| Inconsistent condom use | 0.0 (–) | 100.0 (–) | 95.3 | 93.5 | |

EPP estimated population proportion, SPP sample population proportion

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01

The street-based sex workers had a lower proportion of condom use with regular non-paying partners than establishment-based sex workers (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in condom use with non-regular non-paying partners between the two groups (P > 0.05).

HIV and STD Status

None of the participants were HIV-positive. The prevalence of syphilis, gonorrhea, and Chlamydia among the establishment-based sex workers were 5.7, 8.5, and 3.2%, respectively; correspondingly, among street-based sex workers, they were 15.6, 12.8, and 6.0%, respectively. The difference in prevalence of syphilis between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05). STD infection was defined as having one of the three aforementioned STDs. The prevalence of any of the three STD infections was 16.9% among establishment-based sex workers and 30.1% among street-based sex workers (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4. Prevalence of HIV and STDs among establishment- and street-based FSWs.

| EPP (95% CI) (%) | SPP | χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment-based FSWs (N = 241) | Street-based FSWs (N = 77) | Establishment-based FSWs (N = 241) | Street-based FSWs (N = 77) | ||

| HIV | – | – | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

| Syphilis* | 5.7 (2.6–8.8) | 15.6 (6.3–29.3) | 5.4 | 14.3 | 6.6119 |

| Gonorrhea | 8.5 (3.9–14.1) | 12.8 (5.9–23.6) | 7.6 | 14.3 | 3.1456 |

| Chlamydia | 3.2 (1.1–5.8) | 6.0 (0.7–11.6) | 4.2 | 6.5 | 0.6738 |

| One of the above* | 16.9 (10.7–23.8) | 30.1 (19.2–44.5) | 16.0 | 28.6 | 5.9948 |

EPP estimated population proportion, SPP sample population proportion

P = 0.01

Correlates for Inconsistent Condom Use

Consistent condom use was defined as 100% consistent condom use with all types of sex partners for all types of intercourse during the past week. Multivariate logistic regression showed that being a street-based sex worker and having regular non-paying partners and/or non-regular non-paying partners were independently associated with inconsistent condom use during the past week, after controlling for potential confounders (see footnote to Table 5). The adjusted OR for inconsistent condom use among street- versus establishment-based sex workers was 4.2 (2.0–8.9) (see Table 5).

Table 5. Factors associated with inconsistent condom use: results from multivariate logistic regression (N = 297).

| Independent variable | AOR | 95% CI for AOR |

|---|---|---|

| Street-based FSWa* | 4.244 | 2.027, 8.888 |

| Having regular non-paying partners* | 5.969 | 2.888, 12.340 |

| Having non-regular non-paying partners** | 4.942 | 1.741, 14.030 |

The model controlled for demographic characteristics (including age, years of education, nationality, marriage status, living with sex partner, supporting family), number of clients in the past week, duration of being a sex worker, and charge for commercial sex

P = 0.0001;

P < 0.003

Reference group was the establishment-based FSWs

Discussion

The street-based sex workers had engaged in riskier behaviors when having sex with both commercial and regular non-paying partners. The proportion of inconsistent condom use with clients during the past week was 72.2% (59.0–83.7%) among street-based sex workers and 30.9% (23.3–38.3%) among establishment-based sex workers. The street-based sex workers had a lower proportion of condom use with clients during any type of intercourse. The 2005 behavioral surveillance conducted among establishment-based sex workers may thus give an overly optimistic impression regarding the risk behaviors among FSWs, since it did not include the more risky population, street-based sex workers. The comprehensive behavioral surveillance in Guangdong Province in 2005 showed that 97.1% of FSWs used condoms during their last commercial sex act, which was similar to the proportion among the establishment-based sex workers in our study, but was much higher than among street-based sex workers.

The results of our study suggest that a fairly high proportion of FSWs engage in anal sex with clients, and do not consistently use condoms. Street-based sex workers had a higher proportion engaging in anal sex with clients and a lower proportion of condom use for anal sex during the past week (10.4% of them engaged in anal sex, but none used condoms consistently) than establishment-based sex workers (3.1 and 46.6%, respectively). These two risk factors put FSWs at greater risk for HIV and other STDs, and increase the likelihood that they will infect their partners. Although nobody in our study was found to be HIV-positive, HIV risk behaviors were not unusual among the FSWs.

A higher proportion of the street-based sex workers were supporting their family than establishment-based sex workers, which suggested greater economic pressure among the street-based sex workers. They also had a longer duration in sex work, and charged less than establishment-based sex workers, which imposed further economic pressure. Half (51.9%; 40/77) of the street-based sex workers had previously been establishment-based sex workers. The street-based sex workers were more likely to agree to sex without condoms when offered more money, which also reflected greater economic pressure. Thus, economic pressure may explain in part why street-based sex workers engage in more risk behaviors than establishment-based sex workers.

The street-based FSWs were less educated than the establishment-based sex workers, and less likely to successfully negotiate condom use. This suggests that street-based sex workers may have less knowledge and are less skillful in negotiation. A lower proportion of street-based FSWs had ever been tested for HIV, which suggested that street-based FSWs may have lower self-perception of their risk for HIV infection or more fear of testing. This study also revealed that the prevalence of STDs was higher among street-based FSWs than among establishment-based FSWs; street-based FSWs were more vulnerable to infection. Thus, street-based FSWs should be specifically targeted in future HIV and STD intervention programs. The intervention programs targeting FSWs should, in the future, not only emphasize health education, including improving knowledge and enhancing negotiation skills for condom use, but also address their economic issues.

Condom use among both establishment- and street-based sex workers was much lower with regular non-paying partners than with clients. Having regular non-paying sex partners and having non-regular non-paying sex partners were independently associated with inconsistent condom use. This indicates that the non-paying partners of FSWs need to be targeted by intervention programs. To the extent that they have sex with other partners who also have other partners, they may increase the spread of STDs and HIV to the general population.

None of the participants had injected drugs, and only a few reported that their partners had ever injected drugs. This may be the main reason why no participants in our study were HIV-positive. Tran et al. [18] found that FSWs in Hanoi were much more likely to be HIV-infected if they injected drugs. The extent of the HIV epidemic among FSWs is determined in part by the overlap of IDUs and FSWs. Although the HIV epidemic is concentrated among IDUs in Guangdong Province, HIV prevalence is not high among FSWs, due to the small overlap between the two populations. The HIV sentinel surveillance conducted in rehabilitation centers showed the HIV prevalence among FSWs varied from 0.0 to 1.68% in 2008 and 2009 in Guangdong Province, while the surveillance conducted in the community showed no HIV among FSWs (0.0%) [19]. In a prefecture in Guangdong Province where the HIV prevalence among IDUs was over 20%, no FSWs were found to be HIV-positive in a study conducted there in 2005, which used two-stage cluster sampling to recruit FSWs in the community. Since drug-using FSWs are more likely to be put into re-education centers, the proportion of IDUs among FSWs in the HIV sentinel surveillance conducted in the re-education centers showed a higher proportion of overlap of the two populations. Ding et al. [20] reported that only 2.2% of the FSWs were IDUs in a study in Zhengzhou, and that two of the 621 FSWs were HIV-positive. Lau et al. [21] reported that 3.2% of the 15,379 FSWs surveyed in Sichuan Province were IDUs, and no FSWs in Hong Kong were HIV-positive [22].

Although no participants in our study were found to be HIV-positive, risk behaviors were frequent among them. This study found a relatively high prevalence of STDs among FSWs, which reflects a high frequency of risk behaviors. FSWs are a potentially important bridge for spreading the HIV epidemic into the general population if the prevalence increases in other risk groups or among their clients. Thus, FSWs and their clients/partners should be particularly targeted for intervention efforts.

RDS was used to sample FSWs in this study. It is a new form of chain referral sampling that strives to produce an unbiased indicator for population estimates by adjusting for the biases inherent in the referral recruitment when the sample reaches “equilibrium” [12]. In this program, the overall equilibrium with respect to social and demographic characteristics, including age group, education level, marriage status, currently supporting family, and working venues, was obtained after two to ten waves for most seeds, but it was reached on only one parameter, “currently supporting family”, for the seed ending in two waves. However, the number of the participants recruited by the four seeds ranged from three to 209. The sample was dominated by the 209 participants recruited by one of the four seeds, which may have resulted in selection bias.

Although RDS can reduce the non-response bias through a dual financial incentive and peer pressure, it may still suffer from non-response bias. Because we did not collect information on persons who rejected the coupons in our study, we could not compare the characteristics of those who accepted a coupon to those who rejected it, nor could we evaluate the selection bias of seeds. There was also a high probability of information bias. Some participants might not provide accurate information on certain sensitive questions such as sexual behavior and drug use. The information on condom use and drug use may have suffered from social desirability biases. Finally, this study was cross-sectional, which does not permit causal inferences. Nonetheless, this study identifies the need to provide intervention programs for sex workers, particularly street-based sex workers in Guangdong, and identifies non-regular partners as a particularly risky group of sex worker partners.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zunyou Wu, Feng Deng, Ruiheng Xu and Yurun Zhang, for their valuable support. We are grateful to the staff of the Institute of HIV/AIDS Control and Prevention, Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the staff of the Zhaoqing Dermatology and STD Hospital and Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Zhaoqing Prefecture for their contributions to the conduct of the study, and to Wendy Aft for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript. This study was supported by NIH Fogarty International Center training grant D43 TW000013.

Contributor Information

Yan Li, Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China; Department of Epidemiology, UCLA School of Public Health, Box 951772, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772, USA.

Roger Detels, Department of Epidemiology, UCLA School of Public Health, Box 951772, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772, USA, detels@ucla.edu.

Peng Lin, Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China.

Xiaobing Fu, Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China.

Zhongming Deng, Zhaoqing Institute of Health Inspection, Zhaoqing, China.

Yongying Liu, Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China.

Guohua Huang, Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Zhaoqing Prefecture, Zhaoqing, China.

Jie Li, Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, China.

Yihe Tan, Zhaoqing Dermatology and STD Hospital, Zhaoqing, China.

References

- 1.Lin P, Wang Y, Li Y, Liu J, Zhao J, Kim A. HIV infection—Guangdong Province, China, 1997–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(15):396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health, Guangdong. Update on HIV/AIDS epidemic in Guangdong. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province. HIV/AIDS epidemiology annual report 2008 in Guangdong Province, China. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. Guidelines for second generation HIV surveillance. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joesoef MR, Kio D, Linnan M, Kamboji A, Barakbah Y, Idajadi A. Determinants of condom use in female sex workers in Surabaya, Indonesia. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(4):262–5. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abellanosa IP, Manalastas R, Ghee AE, et al. Comparison of STD prevalence and the behavioral correlates of STD among registered and unregistered FSWs in Manila and Cebu City, Philippines. NASPCP Newslett. 1995 Apr-Jun;:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pickering H, Okongo M, Nnalusiba B, Bwanika K, Whitworth J. Sexual networks in Uganda: casual and commercial sex in a trading town. AIDS Care. 1997;9(2):199–207. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gysels M, Pool R, Nnalusiba B. Women who sell sex in a Ugandan trading town: life histories, survival strategies and risk. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(2):179–92. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P. Factors related to condom use among four groups of female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Educ Prev. 1998;10(1):34–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter KH, Harry BP, Jeune M, Nicholson D. HIV risk perception, risk behavior, and seroprevalence among female commercial sex workers in Georgetown, Guyana. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1997;1(6):451–9. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891997000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran TN, Detels R, Lan HP. Condom use and its correlates among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(2):159–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34:193–239. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston LG, Sabin K, Mai TH, Pham TH. Assessment of respondent driven sampling for recruiting FSWs in two Vietnamese cities: reaching the unseen sex worker. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6 Suppl):i16–28. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9099-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Detels R. An approach to improve validity of response in a sexual behavior study in a rural area of China. AIDS Behav. 1999;3(3):243–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.RDS Incorporated. RDS analysis tool v5.6 user manual. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran TN, Detels R, Long HT, Lan HP. Drug use among female sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam. Addiction. 2005;100:619–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Guangdong Province. HIV/AIDS epidemiology annual report of Guangdong (2008) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding Y, Detels R, Zhao Z, et al. HIV infection and sexually transmitted diseases in female commercial sex workers in China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(3):314–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau JT, Zhang J, Zhang L, et al. Comparing prevalence of condom use among 15,379 FSWs injecting or not injecting drugs in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(11):908–16. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3180e904b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau JT, Ho SP, Yang X, Wong E, Tsui HY, Ho KM. Prevalence of HIV and factors associated with risk behaviors among Chinese female sex workers in Hong Kong. AIDS Care. 2007;19(6):721–32. doi: 10.1080/09540120601084373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]