Abstract

We evaluate the efficacy of a family-based intervention over time among HIV-affected families. Mothers Living with HIV (MLH; n=339) in Los Angeles and their school-aged children were randomized to either an intervention or control condition and followed for 18 months. MLH and their children in the intervention received 16 cognitive-behavioral, small-group sessions designed to help them maintain physical and mental health, parent while ill, address HIV-related stressors, and reduce HIV-transmission behaviors. At recruitment, MLH reported few problem behaviors related to physical health, mental health, or sexual or drug transmission acts. Compared to MLH in the control condition, intervention MLH were significantly more likely to monitor their own CD4 cell counts and their children were more likely to decrease alcohol and drug use. Most MLH and their children had relatively healthy family relationships. Family-based HIV interventions should be limited to MLH who are experiencing substantial problems.

Keywords: HIV+ Mothers, Family interventions, Parenting behaviors, Sexual behavior, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

Mothers living with HIV (MLH) experience predictable challenges in maintaining healthy behaviors and medical regimens. Their children experience heightened stress, frequently demonstrate problem behaviors, and are less likely to successfully achieve developmental milestones [1, 2]. This study evaluated the efficacy of a family intervention designed to improve the behavioral, social, and mental health outcomes of MLH and their children.

In the early 1990s, in New York City (NYC), we demonstrated that meeting with other HIV-affected families in small groups benefitted both MLH and their children [2-5]. Project Teens and Adults Learning to Communicate (Project TALC) found that adolescents in the intervention compared to the control condition were significantly less depressed and anxious, reported fewer conduct problem behaviors, delayed sexual debut, had fewer sexual partners over time, used fewer drugs, had fewer children and at a later age, and, when they did have children, created better home environments for their babies. These substantial benefits must be replicated to justify broad diffusion of any evidence-based program [6].

The “gold standard” for the development of evidence-based practice is to replicate results in multiple efficacy trials. While the logic of this program of development is sound, the realities of changes in disease treatment can often complicate the possibility of such a linear development.

As the profile of the HIV pandemic is constantly shifting, prevention and care have changed from the early-1990s to today. With the introduction of increasingly effective antiretroviral therapies in 1996, the lifespan and quality of life for people living with HIV has increased dramatically [7]. The radical changes in medical treatment and community resources, since that time, necessitated that Project TALC adapt from its original implementation to minimize elements focused on parental death, bereavement, and custody planning, and instead emphasize skills needed to meet the daily challenges of living with a chronic illness. While this intervention trial was originally conceived as an efficacy trial of the original intervention, an unmodified version of the intervention would have been highly problematic given the changing nature of HIV care from the time of the first trial to the current trial. As such, readers may wish to consider this trial an efficacy test of an adaptation of a program with demonstrated efficacy.

In addition, the number of people infected with HIV has stabilized, regionally and in major cities [8]. HIV infection in the 1980s and 1990s was often linked to lifetime histories of injection drug use, which has historically been more of a problem on the U.S. east coast [9, 10]. The current study was mounted in Los Angeles (LA), California, 10 years after implementation of the New York City based (NYC) intervention. MLH enrolled in the LA study were either African-American or Latina, with low rates of injection drug use.

To increase sustainability, the TALC intervention was shortened from 24 to 16 sessions and we eliminated any focus on post-death family adjustment. We tested the hypothesis that MLH and their children who received the TALC intervention would demonstrate better adjustment over time in multiple areas than MLH and their children who did not receive the intervention. The primary hypotheses of the intervention trial were as follows: MLH mothers in the intervention condition, relative to those in the control condition, were hypothesized to show decreased engagement in unprotected sex with serodiscordant partners, reduced substance use, improved adherence to antiretrovirals, reduced numbers of missed medical appointments, and reduced emotional distress. Adolescents of MLH in the intervention condition, relative to those in the control condition, were hypothesized to have reduced substance use, reduced sexual risk-taking, reduced externalizing behaviors and reduced internalizing symptoms. For families, we hypothesized that the intervention would reduce family conflict and increase family cohesiveness.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all sites and voluntary informed consent was obtained from all MLH and their children. MLH aged 21 to 69 years were recruited in LA County between January 2005 and October 2006. MLH were recruited after being approached in clinic waiting rooms (n = 7 medical settings), being referred by providers or peers to study staff, approaching members of the study staff after presentations to support groups, or after reading promotional posters/flyers posted at participating agencies. The healthcare providers referring MLH to the study secured consent to contact potential participants.

We have published a detailed report on the recruitment and intervention retention issues which arose in the course of this study [11]. Approximately 53% of respondents were recruited directly from medical care settings, 42% from non-medical HIV/AIDS service organizations, and 5% from peer referral.

Recruitment

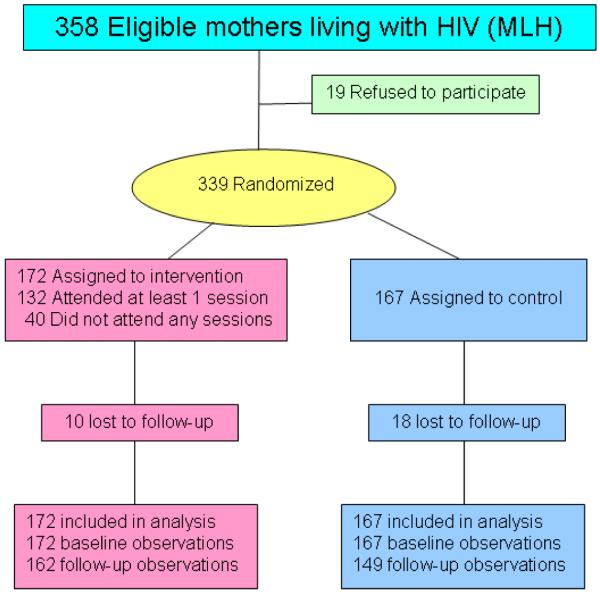

MLH were eligible for recruitment if they were mothers or primary female caregivers of at least one child between the ages of 6 and 20 years and were enrolled in HIV-related clinical care. Of the 358 eligible MLH (Fig. 1), 94% completed the baseline interview (n = 339) and 259 of their school-age children, aged 12 to 20 years, were enrolled (refusal rate: 6%; 52% of mothers had children age 6-11, 26% had one eligible child 12-20, 22% had multiple eligible children). All children of eligible mothers were allowed to enroll in the study. There were 14 perinatally infected youth in the study. As in the NYC study, all adolescents, regardless of age, participated in the same intervention groups. Randomization was conducted immediately after finishing the baseline interviews by telephoning a central data coordinator. Randomization was computerized and assigned each MLH to a condition with 50% probability.

FIGURE 1.

Study Randomization Design & Participant Flow.

Retention

Most mothers (68%) and their adolescents (71%) were assessed across all four time points (i.e., baseline and follow-ups at 6-, 12-, and 18-months). Follow-up rates for mothers were 84% at 6 months, 84% at 12 months, and 78% at 18 months. The percentage of mothers with at least one follow-up (92%) and mothers lost to follow up (8%) did not significantly differ between the MLH intervention and control conditions.

Assessment Procedures

Using laptop computers, an ethnically diverse team of interviewers administered audio computer-assisted self interviews to collect information from participants. Interviewer training included research ethics, emergency crisis protocols, intensive review of assessment protocols, and mock interviews. Quality assurance interviews were conducted initially with 20% of audio-taped interviews, which decreased to 10% over time. Interviewers met or exceeded expectations on 95% of tapes reviewed; remedial training was provided to interviewers when necessary. All participants were paid $30 (U.S.) as an incentive for completing each of the baseline, 6, and 12-month follow-up assessments, and received $35 for completing the 18-month follow-up assessment. MLH were compensated for transportation costs and child care for the intervention sessions they attended. Adolescents were provided with gifts valuing less than $10 per session.

Intervention for MLH and their children

MLH and their adolescents were randomized to the intervention or control condition [11]. MLH in the control condition were offered the intervention after 18 months. For MLH, intervention goals were to: 1) improve parenting while ill (i.e., reduce family conflict, improve communication, and clarify family roles); 2) reduce mental health symptoms; 3) reduce sexual and drug transmission acts; and 4) increase medical adherence and assertiveness with medical providers [12]. For adolescents, the intervention goals were to: 1) improve family relationships; 2) reduce mental health symptoms; 3) reduce multiple problem behaviors (e.g., drug use, criminal acts, school problems, teenage pregnancy); and 4) increase school retention. The intervention was delivered in either English- or Spanish-speaking groups of five to eight MLH, twice weekly for 1.5 to 2 hours each, over eight weeks (n = 16 sessions) [13]. MLH and Adolescent sessions met concurrently in separate groups for 12 of 16 sessions; 4 sessions included both adolescents and MLH together in the same group. (The intervention manual is available at http://chipts.cch.ucla.edu/manuals.) Overall, 77% of MLH attended at least one intervention session, and among women attending at least one session, 81% attended 12 or more of the 16 offered. Of the 116 eligible adolescents, 64% attended at least one session, and 66% attended 12 or more sessions.

Intervention facilitators attended weekly clinical supervision meetings where video tapes of sessions were reviewed with the clinical supervisor. In addition, 20% of videotapes were rigorously evaluated for treatment fidelity; remedial training was provided as needed.

MEASURES

Recent events covered behaviors over the past six months. Mothers’ Sociodemographics included age, gender, ethnicity, years of education, employment, number of persons living in the household, income per household member, and marital status. Conflict was measured by the Conflict Tactics Scale (Form A) [14] which measured the frequency from “never” to “every time” (0-6) of parent-child interactions. The 14 scale items included overall conflict, reasoning, verbal aggression, and violence. This measure has been assessed previously for reliability with samples of African American and Latina mothers [15].

Parenting behaviors were assessed on a 30-item Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory (Form A; AAPI) [16, 17], most of these subscales have been shown to be appropriate for minority participants [18]. For the present analysis, subscales for appropriate expectations (α = 0.51), obedience (α = 0.71), and role reversal (α = 0.78) were used. Family Functioning [19] was adapted to consist of 21 statements reflecting themes of cohesion (α = 0.88), expressiveness (α = 0.78), conflict (α = 0.60), sociability (α = 0.67), an external locus of control (α = 0.71), a democratic family style (α = 0.68), and laissez-faire style (α = 0.58).

Mental health was assessed by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [20] which has been tested on minority populations for validity and reliability [21]. In the present study, scales for anxiety, depression, and a global distress index (all α > 0.71) were used.

Self-reports of sexual behavior were obtained for the number of lifetime and recent sexual partners. Serodiscordant partners were defined as having either an unknown HIV serostatus or opposite serostatus from that of the mothers in the study.

Lifetime and recent prevalence of substance use, such as using alcohol, marijuana, and hard drugs (i.e., barbiturates, cocaine or crack, hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, opiates or painkillers) were measured [22]. Recent reports of use included the number of days of use over the past 90 days, grouped as: “never” (0), “used only once [in past 90 days]” (1), “less than one day a month” (2), “1 to 2 days a month” (3), “3 to 4 days a month” (9), “1 to 2 days a week” (12), “3 to 4 days a week” (36), “5 to 6 days a week” (60), or “every day or almost every day” (90).

HIV health-related variables were assessed for MLH and included self-reported CD4 count, annual number of doctor visits, self-reported 100% adherence to HIV medications over the past three days, and HIV-related coping style items from the Dealing with Illness Inventory [23, 24], in which items were grouped into positive (α = 0.84) and negative coping styles (α = 0.79).

Similar to mothers, adolescents’ demographics were assessed. School attendance, grade level, and most recent grade point average (GPA) were self-reported by the children. Conflict Tactics Scale, Family Functioning, AAPI, and BSI were also utilized with adolescents.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [25] was completed by MLH for children aged 6 to 18 years; children over the age of 12 completed the Youth Self-Report Inventory for themselves. The CBCL has been tested for validity in use with ethnic minority populations of youth [26]. Internalizing and externalizing symptom t-scores were calculated across the full set of items.

Multiple problem behaviors [2] were summed as the presence (1) or absence (0) of recent unprotected sexual intercourse, alcohol use prior to sexual intercourse, contact with the criminal justice system, suicide attempts, hard drug use, and lifetime pregnancy. All individual items were based on self-report, dichotomized and then summed to create the final composite score.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We calculated the needed sample size to compare family adjustment measures and HIV-transmission behaviors between MLH in the intervention and the control condition using RMASS2 software [27]. We assumed 80% power, a type I error of 0.05 for a two-sided test, four repeated measurements from baseline to 18 months at 6-month intervals, and an attrition rate of 5% between follow-ups.

Demographics and background characteristics were compared between MLH in the intervention and MLH in the control, as well as between MLH in the current study and MLH in the TALC study conducted in NYC 10 years earlier [2-5]. Chi-square tests were applied to categorical measures and t tests were applied to continuous measures. Mental health symptom comparisons were conducted separately for adolescent boys and girls in the current study using t tests [20].

Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted examining parent and adolescent outcomes over time using mixed-effect regression models using random intercepts and slopes from baseline to 18 months between the intervention and control samples. Covariates included treatment assignment for the HIV-affected samples and time from the baseline assessment; interaction effects were examined for both linear and quadratic effects. Quadratic effects were identified at the time point where the zero slope occurred (−ßlinear/2ßquadratic) and the slope changed valence.

Linear regressions were applied to continuous outcomes (PROC MIXED) and logistic regressions were applied to binomial outcomes (PROC GLIMMIX). Zero-inflated Poisson models (NLMIXED) [28] were applied to sexual behavior and substance use count data to account for the high proportion of zero counts; results are reported as two outcomes for the probability of engaging in the behavior (e.g., use or no use), and the frequency of engagement among those who engage in the behavior (e.g., frequency of use among users). Random effects were included in the models to account for correlations between nested observations (e.g., repeated observations over time for a MLH). Linear regressions on adolescent outcomes included random intercepts for each adolescent’s mother.

RESULTS

MLH were predominantly Latino (63%) or African-American (30%), 40 years of age, and had three children (Table 1). Typically, one child’s age was eligible for enrollment (62%; range 1-6). Most MLH had less than a high school education and were struggling to survive economically. Only one-third were employed and about half had health insurance.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Mothers Living with HIV (MLH) at Recruitment.

| MLH Intervention n = 172 |

MLH Control n = 167 |

Total n = 339 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 40.8 | (8.1) | 39.6 | (8.2) | 40.2 | (8.2) |

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| Latino | 111 | (64.5) | 118 | (70.7) | 229 | (67.6) |

| White | 5 | (2.9) | 7 | (4.2) | 12 | (.5) |

| African American | 52 | (30.2) | 39 | (23.4) | 91 | (26.8) |

| Other | 4 | (2.3) | 3 | (1.8) | 7 | (2.1) |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 112 | (65.5) | 105 | (63.3) | 217 | (64.4) |

| High school or GED | 59 | (34.5) | 61 | (36.7) | 120 | (35.6) |

| Currently employed | 45 | (28.8) | 44 | (28.0) | 89 | (28.4) |

| Financial status | ||||||

| Struggling to survive | 39 | (22.7) | 40 | (24.0) | 79 | (23.3) |

| Barely paying the bills | 70 | (40.7) | 65 | (38.9) | 135 | (39.8) |

| Have necessities | 51 | (29.7) | 49 | (29.3) | 100 | (29.5) |

| Comfortable | 12 | (7.0) | 13 | (7.8) | 25 | (7.4) |

| Mean number of children (SD) | 3.1 | (1.6) | 3.3 | (1.9) | 3.2 | (1.8) |

| Have romantic partner | 96 | (55.8) | 83 | (49.7) | 179 | (52.8) |

| Married to romantic partner | 31 | (32.3) | 31 | (37.3) | 62 | (34.6) |

| Sexual behavior | ||||||

| Number of sexual partners during lifetime | ||||||

| One | 35 | (21.2) | 34 | (21.1) | 69 | (21.1) |

| More than one | 130 | (78.8) | 127 | (78.9) | 257 | (78.8) |

| Number of sexual partners during past 6 months | ||||||

| None | 75 | (45.5) | 76 | (47.2) | 151 | (46.3) |

| One partner; protected sex only | 50 | (30.3) | 53 | (32.9) | 103 | (31.6) |

| One partner / unprotected discordant sexa | 40 | (24.2) | 32 | (19.9) | 72 | (22.1) |

| Mean number of unprotected discordant actsa | 3.4 | (17.7) | 1.0 | (3.6) | 2.2 | (12.9) |

| Substance use | ||||||

| Lifetime rates | ||||||

| Alcohol | 108 | (64.7) | 98 | (60.1) | 206 | (62.4) |

| Marijuana | 58 | (34.7) | 45 | (27.6) | 103 | (31.2) |

| Hard drugs | 67 | (40.1) | 66 | (40.5) | 133 | (40.3) |

| Rates during past 6 months | ||||||

| Alcohol | 36 | (21.3) | 44 | (26.8) | 80 | (24.0) |

| Marijuana | 16 | (9.5) | 14 | (8.5) | 30 | (9.0) |

| Hard drugs | 20 | (11.8) | 31 | (18.9) | 51 | (15.3) |

| Number of days using during past 3 months | ||||||

| Alcohol | 1.5 | (7.3) | 2.1 | (8.4) | 1.8 | (7.9) |

| Marijuana | 2.0 | (11.2) | 2.9 | (14.4) | 2.4 | (12.9) |

| Hard drugs | 1.4 | (9.0) | 4.9 | (18.5) | 3.1 | (14.6) |

| General health | ||||||

| Have health insurance | 90 | (52.3) | 87 | (52.1) | 177 | (52.2) |

| Mean number of visits to doctor during past year (SD) |

9.2 | (8.1) | 8.7 | (7.4) | 9.0 | (7.8) |

| Mean percent of missed visits (SD) | 0.2 | (0.2) | 0.1 | (0.2) | 0.1 | (0.2) |

| 100% Adherence to antiretrovirals | 105 | (80.2) | 95 | (72.5) | 200 | (76.3) |

| Undetectable viral load | 99 | (62.3) | 97 | (63.4) | 196 | (62.8) |

| Mental health, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Higher life expectancy | 38.3 | (7.1) | 37.9 | (6.7) | 38.1 | (6.9) |

| Brief Symptom Inventory global distress | 0.7 | (0.6) | 0.7 | (0.6) | 0.7 | (0.6) |

Discordant partner has opposite HIV serostatus as mother in the study or serostatus was unknown.

Note: None of differences between MLH intervention and MLH control were significantly different.

MLH reported few HIV-transmission acts at baseline: 29% only had one sexual partner during their lifetime. Only 55% were currently sexually active, 26% had unprotected sex with serodiscordant partners, 27% used alcohol, and 12% used hard drugs.

MLH were similar across conditions on age, ethnicity, education, perceived financial status, employment, the presence of a romantic partner, marital status, having health insurance, number of children, self-reported CD4 counts, and the number of medical visits during the past year (median = 6, range = 0-52). Consistent adherence to antiretroviral medications was also high and similar across conditions (76%); 63% had an undetectable viral load. Intervention MLH received their HIV diagnosis earlier compared to control MLH (8.5 vs. 7.0 years prior, t = 2.34, df = 330, P = 0.02).

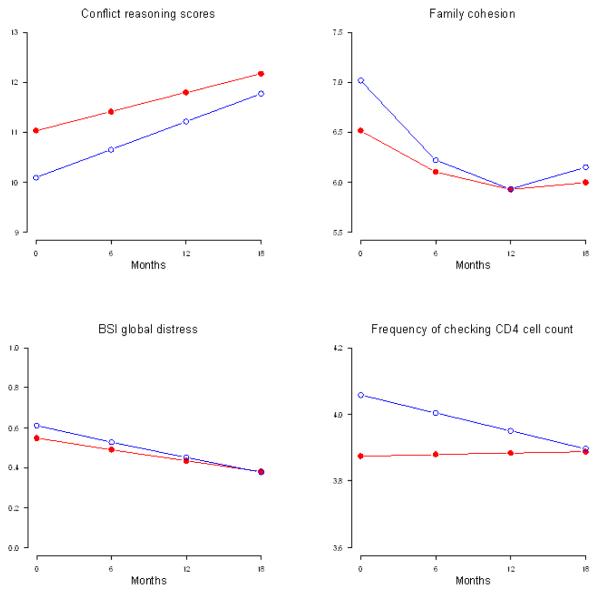

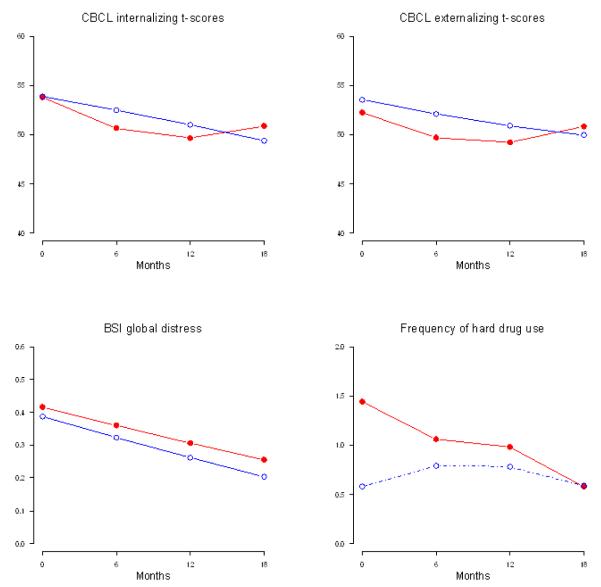

Figures 2 and 3 show adjusted mean scores for key outcomes estimated by the mixed-effect regression models for parents and adolescents. At baseline, MLH were similar across condition on family conflict, AAPI parenting measures, mental health, sexual behavior, and HIV-related coping. MLH differed across conditions on several of the Family Functioning scales. Intervention MLH reported higher levels of conflict (t = 2.05, df = 492, P = 0.04), having a less democratic style (t = −2.57, df = 487, P < 0.01), and lower levels of cohesion (t = −2.39, df = 490, P = 0.02). Intervention MLH were less likely to check their CD4 count (t = −2.57, df = 484, P = 0.01) and use hard drugs (t = −2.26, df = 817, P = 0.02) at baseline.

FIGURE 2.

Plots of Estimated Means over 18 months for Mothers by Intervention Condition ( ) and Standard Care Condition (o).

) and Standard Care Condition (o).

FIGURE 3.

Plots of Estimated Means over 18 months for Adolescents by Intervention Condition ( ) and Standard Care Condition (o).

) and Standard Care Condition (o).

For most outcomes, MLH did not significantly differ between the intervention and control condition over time. Significant differences that did occur tended to minimize baseline differences. For example, control MLH checked their CD4 counts more frequently than intervention MLH at baseline (t = 2.57, df = 484, P = 0.01) and decreased their frequency of checking relative to intervention MLH over time (Fig. 2; t = −2.08, df = 484, P = 0.04). Family cohesion (Fig. 2) decreases less in intervention MLH compared to control MLH over one year (linear est = 0.086, t = 2.33, df = 490, P = 0.02). However, family cohesion decreased in intervention MLH during the second year compared to control MLH (quadratic est = −.0037, t = − 1.95, df = 490, P = 0.05). Similarly, laissez-faire parenting decreased for 10 months and then increased over 18 months in intervention MLH compared to control MLH (linear est = −.069, t = −2.05, df = 485, P = 0.04; quadratic est = .0034, t = 1.97, df = 485, P = 0.05). Alcohol-using MLH drank more frequently in the intervention compared to the control Condition over time (t = 4.96, df = 338, P < 0.01).

Adolescents of MLH

The school-age children were 15 years old on average; 84% were in school, 16% were employed, and 27% had experienced sexual debut. Adolescents reported few problem behaviors: only 21% reported more than one problem act. On average, adolescents reported fewer mental health symptoms than normative samples of same-age peers at baseline; all comparisons were significantly different (t = −2.25 to −9.94, df = 964 for girls and 1699 for boys, all P < .05) except for female depression (t = −1.41, df = 964, P = 0.16). Ten percent reported clinically-significant internalizing or externalizing symptoms. Among the 43% who had been tested for HIV, 14% were HIV-positive.

At baseline, the MLH’s children were similar across condition in ethnicity, age, gender, school attendance, employment, and delinquency. At baseline, adolescents in the intervention and control conditions gave similar reports of their adjustment, GPA, mental health, and rated their parents’ skills on the AAPI and Family Functioning Scales similarly. CBCL t-scores remained in the normal range (t scores < 67) over time (Fig. 3). Compared to same-age peers, fewer youth of MLH were sexually active or used drugs. Similar to their parents, most adolescent outcomes did not significantly differ between intervention and control over time.

While alcohol, marijuana, and hard drug use rates remained similar across conditions, the frequency of use among users decreased significantly more in the intervention compared to the control condition (Fig. 3; t = −2.36, df = 256, P = 0.02 for alcohol users and t = −3.46, df = 256, P < 0.01 for hard drug users); the frequency of marijuana use increased in the intervention compared to the control condition (t = 5.97, df = 256, P < 0.01). Both CBCL internalizing and externalizing behaviors reported by MLH decreased significantly over time in both the intervention and control conditions at similar rates.

DISCUSSION

Ten years ago, a family intervention with MLH in NYC substantially benefited parents and children for over 6 years [2-5]. Not only did the family benefit, but grandchildren who were not yet born when the intervention was delivered also benefited. The parents’ and their adolescent children’s mental health and quality of life improved. Simultaneously, their problem behaviors, hard drug use, and sexual transmission risk decreased. The number of babies born to adolescent girls, their number of sexual partners, and unprotected sexual risk acts were significantly lower in response to the intervention.

Many of the benefits observed in NYC were not seen in the LA sample. Mental health symptoms, risky substance use and sexual acts, and adjustment indices were similar across the intervention and the standard care conditions in LA. The intervention had significantly fewer benefits. Rarely does the literature on behavioral interventions for persons living with HIV publish reports on null findings. We believe that it is important to share successes, as well as failures. Our power calculations make it clear that our non-significant results cannot be attributed to insufficient sample size. What we believe is that the differences in effectiveness observed across the two studies is likely due to changes in the risk profiles of MLH over the last 15 years in the epidemic in the United States. In 1994, when the NYC sample was recruited, NYC had 30% of all cases of MLH. The sociodemographic profile of MLH in the NYC sample reflected the sociodemographics very closely of MLH in the United States. Similarly, the LA sample, recruited 10 years later had very different risk profiles and the Latinos were from different countries (Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico compared to Mexico and South America). Yet, the LA sample also closely matched the national sociodemographic profile of the CDC’s profile of MLH in the United States in 2005-2006. Each sample reflected the sociodemographics of HIV at the time of their recruitment. The risk of the profile of each sample reflects the national profile of MLH at the time of recruitment.

Alternatively, the difference in intervention effectiveness from the NYC trial to the LA trial may be a result of selection bias in the sampling strategies of each cohort. The systems of care for HIV/AIDS in NYC during the 1993-1995 recruitment period were very different from the system of care in LA in the 2005-2006 period. In NYC a directory of all financially needy persons with AIDS was kept by the Division of AIDS Services in New York City; this directory was the sampling frame for the original trial. In LA, there was no comparable centralization of services and no comparable directory. As a result, in LA the sample was drawn from women currently seeking medical and/or social services for HIV/AIDS (with no restrictions on financial need) and were recruited in conjunction with their current engagement with services. In NYC those who had at one time sought care but who had not been recently engaged were sampled, as well as those who were actively seeking care. It is possible that this intervention is more effective among those persons who are less able to access services and care on their own and/or are more financially needy. Detailed records of engagement with services in the original trial were not kept and so this interpretation is speculative.

Moreover, a second possible selection bias may be at work based on city demographics. In NYC the sample was 75% U.S. born whereas in LA only 36% of the sample was U.S. born. In both trials, Latina was the dominant ethnicity, but in NYC the Latina women were largely native-born; whereas, in LA these women were primarily foreign-born in Mexico. Two possible complications arise. One, the TALC intervention may be more appropriate for native-born persons. Two, foreign-born Latinas may be less in need of intervention and will thus evidence smaller intervention gains. Mexican-born women have been reported to engage in fewer risk behaviors, have more positive coping styles, and are healthier than their native-born counterparts [29], suggesting this intervention may be more effective for families who are in greater need.

Finally, the difference in effectiveness may be a reflection of the changing dynamics of how HIV affects families in the United States. HIV-affected families have changed dramatically over the past 10 years: annual HIV incidence has stabilized and the length and quality of life have been extended [6, 7]. Table 3 demonstrates that our LA sample was substantially healthier and had fewer problem behaviors compared to the NYC sample of 1994 (e.g., less drug use, alcohol use, half the number of sexual partners, fewer mental health symptoms). The children of MLH in LA rated as well-adjusted, and adjustment improved over time. The immediate observation is that MLH in LA in 2005 were healthier and had fewer life domains needing improvement. Unfortunately, these data are not epidemiologic data and we cannot definitively assert that the populations of LA women living with HIV in 2005-2006 and NYC women living with HIV between 1993-1995 were different. But it is clear from our data that our two resulting intervention samples differed significantly with respect to risk and need across the two studies and we believe these differences are likely a contributing factor to the differences in efficacy seen across the two studies. HIV-affected families in the United States have a significant safety net: HIV has become a chronic disease. This study suggests that prevention services and interventions aimed at improving families’ adjustment must now be targeted to those in greatest need. This is not the condition globally, especially in high prevalence countries [30]. Adapted interventions for families living with HIV are currently being conducted in South Africa, China, and Thailand, where HIV is not yet a chronic illness and the need for family interventions remains [31].

TABLE 3.

Demographic profiles of HIV-positive mothers, New York 1994–1996 (n = 248) and Los Angeles 2005–2006 (n = 339).

| NY | LA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | * | ||

| African American | 35% | 27% | |

| Latina | 43% | 67.5% | |

| White | 12% | 3.5% | |

| Other | 1% | 2% | |

| Mean Age | 37.4 | 40.2 | * |

| Education | * | ||

| 8th grade or less | 12% | 36% | |

| Some high school | 35% | 28% | |

| High school grad | 28% | 14% | |

| Some college | 17% | 17% | |

| College grad | 8% | 5% | |

| Employed | 5% | 28% | * |

| Financial Status | * | ||

| Struggling to survive | 22% | 23% | |

| Barely paying bills | 33% | 40% | |

| Have necessities | 24% | 30% | |

| Comfortable | 22% | 7% | |

| Born in the United States | 75% | 36% | * |

| CD4+ Count | 188.7 | 519.6 | * |

| Current HIV transmission risk | |||

| Mean number of sex partners | 1.1 | 0.6 | * |

| Mean number of sex acts | 13.8 | 4.7 | * |

| Alcohol use | 64% | 24% | * |

| Injection drug use | 4% | 1% | * |

P < 0.01

We would like to raise three important issues around study design which we do not believe account for the differences in efficacy. First, we do not think the null findings should be attributed to changes in the intervention manual. The intervention, while reduced from 24 to 16 sessions, was primarily changed with respect to dropping the 8 weeks spent on custody planning and coping with bereavement. The core skills, intervention delivery modality, training procedures, and fidelity measurement were unchanged. Second, the measures used to assess outcomes were largely the same as those used in the prior trial, and most all of these measures have been effectively used with ethnic/racial minority populations of adults and adolescents previously. Third, the randomization would appear to have been effective. While there were some baseline differences across family cohesion, frequency of checking CD4 cell counts, and frequency of hard drug use, the samples were non-significantly different across most domains (e.g., for mothers: age, ethnicity, education, financial status, employment, self-reported CD4 cell counts, number of annual medical visits, family conflict, parenting measures, mental health, sexual behaviors, and HIV-related coping; for adolescents: age, gender, school attendance, employment, substance use, internalizing and externalizing behaviors).

The primary limitation of the current study is that we can only speculate as to the possible reasons for the intervention’s null findings. Certainly it would be more satisfying if we were able to pinpoint exactly the cause, but several possibilities present themselves as we discussed above. Ultimately, a combination of sampling biases and/or changes in the populations may be at work. It could be that families of Mexican-born women, relative to families of native-born Latinas, are less in need of intervention (i.e., the Healthy Hispanic Paradox). It could be that women who are healthier with respect to their HIV condition (i.e., higher CD4 counts) are less in need of intervention due to improvements in treatment, especially high-quality antiretroviral therapies. It could be that women who actively go to medical clinics and AIDS service organizations (i.e., proactive service utilizers relative to those who are merely in a registry) are less in need of intervention. Regardless, we believe that there is a central message to be gleaned across these multiple possibilities: interventions for people living with HIV are likely to be most effective if they are directed at those with greater need.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Adolescents of Mothers Living with HIV (MLH) at Recruitment.

| MLH Intervention n = 139 |

MLH Control n = 120 |

Total n = 259 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 14.8 | (2.3) | 15.0 | (2.5) | 14.9 | (2.4) |

| Male gender | 53 | (38.1) | 47 | (39.2) | 100 | (38.6) |

| Currently attending school | 118 | (86.1) | 99 | (82.5) | 217 | (84.4) |

| Currently employed | 21 | (15.1) | 20 | (16.7) | 41 | (15.8) |

| Sexual behavior | ||||||

| Number of sexual partners during lifetime | ||||||

| None | 97 | (72.4) | 85 | (71.4) | 182 | (71.9) |

| One | 14 | (10.4) | 11 | (9.2) | 25 | (9.9) |

| More than one | 23 | (17.2) | 23 | (19.3) | 46 | (18.2) |

| Number of sexual partners during past 6 months | ||||||

| None | 105 | (76.1) | 91 | (76.5) | 196 | (76.3) |

| One partner; protected sex only | 25 | (18.1) | 19 | (16.0) | 44 | (17.1) |

| One partner / unprotected discordant sexa | 8 | (5.8) | 9 | (7.6) | 17 | (6.7) |

| Mean unprotected discordant actsa | 0.0 | (0.1) | 0.1 | (0.5) | 0.0 | (0.3) |

| Unprotected, discordant acts under the influence of alcohol |

1 | (0.7) | 2 | (1.7) | 3 | (1.2) |

| Substance use | ||||||

| Lifetime rates | ||||||

| Alcohol | 56 | (41.2) | 46 | (38.7) | 102 | (40.0) |

| Marijuana | 31 | (22.8) | 31 | (26.1) | 62 | (24.3) |

| Hard drugs | 23 | (16.9) | 14 | (11.8) | 37 | (14.5) |

| Rates during past 6 months | ||||||

| Alcohol | 33 | (23.7) | 32 | (26.9) | 65 | (25.2) |

| Marijuana | 18 | (12.9) | 20 | (16.8) | 38 | (14.7) |

| Hard drugs | 11 | (7.9) | 9 | (7.6) | 20 | (7.8) |

| Number of days using during past 3 months | ||||||

| Alcohol | 1.6 | (6.8) | 1.8 | (6.8) | 1.7 | (6.8) |

| Marijuana | 2.8 | (13.8) | 5.9 | (20.7) | 4.3 | (17.4) |

| Hard drugs | 2.1 | (12.1) | 0.7 | (4.0) | 1.4 | (9.3) |

| Contact with the criminal justice system | ||||||

| Lifetime | 9 | (6.6) | 7 | (5.8) | 16 | (6.3) |

| Past 6 months | 8 | (5.8) | 3 | (2.5) | 11 | (4.2) |

| Pregnancy | ||||||

| Lifetime | 10 | (7.2) | 10 | (8.4) | 20 | (7.8) |

| During the study | 18 | (13.6) | 19 | (16.7) | 37 | (15.0) |

| Suicide attempts, past 6 months | 6 | (4.3) | 3 | (2.5) | 9 | (3.5) |

Discordant partner has opposite HIV serostatus as mother in the study or serostatus is unknown.

Note: None of differences between adolescents of MLH intervention and MLH control were significantly different.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant # R01MH068194 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Rotheram-Borus had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Registration number NCT00988390

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Hoffman D. A longitudinal study of the impact on young children of maternal HIV serostatus disclosure. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;7:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Gwadz M, et al. An intervention for parents with AIDS and their adolescent children. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1294–1302. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee M, Leonard N, et al. Four-year behavioral outcomes of an intervention for parents living with HIV and their adolescent children. AIDS. 2003;17:1217–1225. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200305230-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Lin YY, et al. Six year intervention outcomes for adolescent children of parents with HIV. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:742–748. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Stein JA, Lester P. Adolescent adjustment over six years in HIV-affected families. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flay BR, Biglan A, Boruch RF, et al. Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev Sci. 2005;6:151–175. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-5553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, et al. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:306–311. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marel R, Galea J, Smith RB, et al. Epidemiologic Trends In Drug Abuse: Vol. 2. Proceedings of the Community Epidemiology Work Group. US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, Md: 2006. Drug use trends in New York City; pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkowski B. Epidemiologic trends in drug abuse: Vol. 2. Proceedings of the Community Epidemiology Work Group. US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, Md: 2006. Patterns and trends in drug abuse in Los Angeles, California: a semiannual update; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice E, Lester P, Flook L, et al. Lessons learned from “integrating” intensive family-based interventions into medical care settings for mothers living with HIV/AIDS and their adolescent children. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1005–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Miller S, et al. An intervention for adolescents whose parents are living with AIDS. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;2:201–219. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lester P, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Elia C, et al. TALK: Teens and Adults Learning to Communicate. In: Lecroy CW, editor. Handbook of Evidence-Based Treatment Manuals for Children and Adolescents. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuire J, Earls F. Exploring the reliability of measures of family relations, parental attitudes, and parent-child relations in a disadvantaged minority population. J Marriage Fam. 1993;55(4):1042–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele B. Violence in our society. Pharos. 1970;33:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steele BF, Pollock CD. A psychiatric study of parents who abuse infants and small children. In: Hempe CH, Helfer RE, editors. The Battered Child. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutenbcher M. Psychometric assessment of the Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory in a sample of low-income single mothers. J Nurs Meas. 2001;9(3):291–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloom BL. A factor analysis of self-report measures of family functioning. Fam Process. 1985;24:225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. National Computer Systems, Inc; Minneapolis, MN: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, Ivankovich O. Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: A comparison of African American, Hispanic, and White Patients. Pain Med. 2005;6(1):88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong FL, Lightfoot M, Pequegnat W, et al. Effects of behavioral intervention on substance use among people living with HIV: The Healthy Living Project randomized controlled study. Addiction. 2008;103:1206–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Namir S, Wolcott DL, Fawzy FI, et al. Coping with AIDS: psychological and health implications. J Appl Social Psychol. 1987;17:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy DA, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Marelich W. Factor structure of a coping scale across two samples: do HIV-positive youth and adult use the same coping strategies? J Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;33:627–647. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. University of Vermont; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman RS, Khoury EL, Vega WA, Gil AG, Warheit GJ. Teacher and parent perceptions of behavior problems among a sample of African American, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic White students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23(2):181–197. doi: 10.1007/BF02506935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedeker H, Gibbons R, Waternaux C. Sample size estimation for longitudinal designs with attrition: comparing time-related contrasts between two groups. J Educ Behav Stat. 1999;24:70–93. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall D. Zero-inflated Poisson and binomial regression with random effects: a case study. Biometrics. 2000;56:1030–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sánchez M, Rice E, Stein J, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Acculturation, coping styles, and health risk behaviors among HIV positive Latinas. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(2):401–409. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9618-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter L, Sherr L. Editorial: strengthening families: a key recommendation of the Joint Learning Initiative on Children and AIDS. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Lee S-J, Thammawijaya P, et al. Stigma, social support, and depression among people living with HIV in Thailand. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1007–1013. doi: 10.1080/09540120802614358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]