Abstract

Background

Pituitary antibodies have been reported with greater frequency in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis than in healthy controls, although there is significant variability in the strength of the association and the methodologies used.

Methods

We designed a nested case–control study to characterize the prevalence of pituitary antibodies at the time of the clinical diagnosis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, as well as at 2, 5, and 7 years before diagnosis. Active component female service member cases (n=87) and matched female controls (n=107) were selected using the Defense Medical Surveillance System database (DMSSD) between January 1998 and December 2007. Pituitary antibodies were measured by immunofluorescence using human pituitary glands collected at autopsy as the substrate.

Results

At diagnosis, pituitary antibodies were present in 9% of cases with Hashimoto's (8 of 87) and 3% of controls (3 of 107). When the data were analyzed using a conditional logistic regression model, which takes into account the matching on age and work status, pituitary antibodies increased the odds of having Hashimoto's thyroiditis by sevenfold (95% confidence interval from 1.3 to 40.1, p=0.028), after adjusting for components of the DMSSD-category-termed race and for thyroperoxidase antibodies. Before diagnosis, pituitary antibodies were positive in 3 of the 11 subjects (2 cases and 1 control) at the −2-year time point, and negative in all 11 subjects at the −5- and −7-year time points.

Conclusions

In summary, using a nested case–control design, we confirm that pituitary antibodies are more common in Hashimoto's thyroiditis and suggest that they appear late during its natural history.

Introduction

Hashimoto's thyroiditis is characterized pathologically by four features initially described in 1912: ectopic formation of lymphoid follicles within the thyroid gland, interstitial fibrosis and fat deposition, disrupted thyroid follicles, and transformation of the normal thyroid follicular cells into Hürthle cells (1). Initially considered a rarity, Hashimoto's thyroiditis has now become the most common autoimmune disease (2). Its prevalence is 0.8% when estimated from a review of published articles (3), 4.6% when estimated biochemically from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (4), and >5% when estimated from cytology of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirates of thyroid nodules (5). Hashimoto's thyroiditis can be managed relatively well in most patients by restoring the defective production of thyroid hormones when hypothyroidism develops, but earlier treatments based on disease pathogenesis rather than symptoms would be of value. Like the majority of the other autoimmune diseases (6), Hashimoto's thyroiditis is more common in women (F:M ratio > 10:1) and tends to associate in the same patient (co-morbidity) or the same family (familial aggregation) with other autoimmune diseases, which are often more difficult to manage than thyroiditis itself (7).

Among the diseases that have been reported in association with Hashimoto's thyroiditis is autoimmune hypophysitis (8). The extent of this association is difficult to estimate starting from the prospective of Hashimoto's thyroiditis since thyroiditis is a very common disease where tests of pituitary function or autoimmunity, however, are rarely performed. It might be more informative to look at this issue from the hypophysitis perspective. Approximately 600 patients with primary hypophysitis have been reported in the literature, 30 of which in association with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, yielding a 5% estimate of the association between these two endocrinopathies.

The tool most commonly used in the diagnostic immunology laboratory to detect and monitor an underlying autoimmune disease is the measurement of autoantibodies in the patient's serum. Autoantibodies have been viewed for many years as a mere accompaniment of the underlying disease, rather than mechanistically involved in disease causation. Recent times, however, have witnessed a resurgent interest in autoantibodies since it has been shown that they can predict the appearance of a frank clinical disease several years in advance. For example, antibodies to Ro and La precede by ∼5 years the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (9). In keeping with these findings, we have recently reported in a cohort of female U.S. military personnel that thyroperoxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies precede by at least 7 years the clinical diagnosis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis (10). Using the same patient cohort, we designed the present nested case–control study to assess the prevalence of pituitary antibodies at the time of the Hashimoto's thyroiditis diagnosis and to evaluate their presence prior to clinical diagnosis. We also performed a meta-analysis of previous studies that examined the prevalence of pituitary antibodies among patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Methods

Subjects

This study analyzed 194 active component female service members using a nested case–control design, a design particularly useful to identify biological precursors of disease. Men were excluded because Hashimoto's thyroiditis predominantly affects women so that an oversampling of men would have been required to obtain an acceptable sample size.

Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases (n=87) were selected from a cohort of 543,097 active component female service members between January 1998 and December 2007 using the Defense Medical Surveillance System database (DMSSD). This database maintains records of inpatient and outpatient medical diagnoses, which are coded by the International Classification of Disease, Clinical Modification 9 (ICD-9). Cases were those women who had either one inpatient or at least two outpatient diagnostic codes of Hashimoto's thyroiditis (ICD-9 245.2), and who also had at least four serum samples available for analysis during the serum collection interval specified previously. Of the total 543,097 women, 522 (0.1%) had a diagnosis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and of them 99 met our inclusion criteria.

Controls were apparently healthy female soldiers who did not have Hashimoto's thyroiditis or Graves' disease and who were on active duty on the case's diagnosis date and in the military for at least as long as the oldest serum date of the cases.

The budget for the study allowed the analysis of ∼200 serum samples, so that in the end 87 Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases and 107 age-matched controls became part of the study. The study used de-identified data and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the U.S. Military Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center.

Serum time points

Sera are collected biannually from all active-duty military personnel, as well as before and after each deployment, for human immunodeficiency virus testing. Sera are stored in large walk-in freezers at the Department of Defense Serum Repository (11). All cases and controls (n=194) were studied for pituitary antibodies on serum collected at the time of the clinical diagnosis±6 months. Cases and controls who tested positive for pituitary antibodies were also studied at three time points prior to the clinical diagnosis: 0.5–2 years, 2–5 years, and 5–7 years.

Pituitary, thyroperoxidase, and thyroglobulin antibodies

Pituitary antibodies were measured by immunofluorescence using human pituitary glands as substrate and the method described by Landek-Salgado et al. (12). In brief, a pituitary gland was collected at autopsy from the Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology as soon as possible to the time of death, embedded in O.C.T medium (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), and frozen. Frozen sections were cut on the cryostat (Leica CM1950, Bannockburn, IL), fixed in acetone, and incubated with sera from cases with Hashimoto's thyroiditis or controls, both diluted 1:10 in phosphate-buffered saline. After washing and adding a goat anti-human IgG antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate diluted 1:400, sections were examined with an AxioImager A2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with an AxioCam digital camera and processed with Adobe Photoshop. Sera were considered positive for pituitary antibodies when they produced a staining in the cytosol of numerous anterior pituitary cells.

Thyroperoxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies were measured using commercial kits (INOVA Diagnostics, Inc., San Diego, CA), as described by Hutfless et al. (10), considering positive a value >100 WHO units/mL.

Specificity of pituitary antibodies

To assess the tissue specificity of pituitary antibodies, we tested the positive sera against a control endocrine gland, a human thyroid gland collected at autopsy. To begin characterizing the pituitary cell specificity, the positive sera were tested by double immunofluorescence against growth hormone, the most abundant protein in the pituitary gland, and a candidate autoantigen. The double-immunofluorescence protocol is described in details by Guaraldi et al. (13). Briefly, human pituitary sections were incubated at the same time with the human sera (diluted 1:10) and a goat polyclonal antibody directed against growth hormone (sc-10364; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The human antibodies were then identified by the addition of a green-emitting (fluorescein isothiocyanate) anti-human immunoglobulin secondary antibody, and the hormone staining by the addition of a red-emitting (Cy5) anti-goat immunoglobulin antibody. Images of the same microscope field were acquired with the green and red filter and merged digitally to assess colocalization.

Statistical analysis and meta-analysis

The study aimed to assess whether Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases were more likely to have pituitary antibodies than age-matched controls, controlling for components (white and nonwhite) of the DMSSD-category-termed race, henceforth referred to as race, and thyroid autoantibodies. Since autoantibodies are known to differ by age and race, we eliminated the confounding effect of age by matching the study on age and we adjusted for race by including this in the conditional logistic regression model. Race was coded dichotomously as white and nonwhite as the majority of subjects in the DMSSD were designated as white. All analyses were performed with Stata statistical software, release 12 (College Station, TX), considering a p-value <0.05 statistically significant.

This study also reviewed the literature about pituitary autoimmunity/hypophysitis to identify those studies where pituitary antibodies were measured in both Hashimoto's thyroiditis and healthy controls. In particular, we have been systematically collecting all articles published on pituitary autoimmunity/hypophysitis in various languages. Articles are identified using PubMed [hypophysitis OR adenohypophysis OR infundibul* OR (lympho* AND hypophys*) OR (autoimmu* AND hypophys*) OR (Lympho* AND adenohypophys*) OR (autoimmu* AND pituit*)] and Google Scholar [hypophysitis] searches, as well as from citations found in the articles identified previously. A total of 748 articles have been published on this topic from 1925 to present, and are available for download at this website: http://pathology2.jhu.edu/hypophysitis/resources.cfm. Of them, 67 have reported on pituitary antibodies and of these 10 have measured pituitary antibodies in both patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and healthy controls, spanning a two-decade period from 1988 to 2008 (14–23). None of these 10 studies accounted for confounding factors such as age, race, or presence of thyroid antibodies in the published results. Meta-analysis was used to calculate a summary statistic (the odds ratio [OR]) for each study, followed by the calculation of a weighted average of the ORs across the studies using a fixed-effect model. Since 2 of the 10 studies (14,22) had zero in one cell of the 2×2 table, the Peto method was used for estimating summary ORs (24).

Results

Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases and controls were similar with respect to age, the matching factor, but tended to differ for race since cases were more likely to be white than controls (Table 1). Thyroperoxidase and thyroglobulin antibodies were, as expected, significantly higher in cases than controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Autoantibody Features of Hashimoto's Thyroiditis and Age-Matched Controls in Female Active-Duty Military Personnel, 1998–2007

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases | Controls | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 87 | 107 | |

| Agea at index dateb: mean (±SD) | 33 (±7) | 33 (±7) | 0.98 |

| Race: | |||

| White (n,%) | 57 (66%) | 56 (52%) | 0.06 |

| Nonwhite (n,%) | 30 (34%) | 51 (48%) | |

| TPO antibodies: mean (±SD) | 790 (±691) | 147 (±364) | <0.0001 |

| Tg antibodies: mean (±SD) | 394 (±560) | 50 (±133) | <0.0001 |

| Pituitary antibodies: n (%) posit. | 8 (9.2%) | 3 (2.8%) | 0.028c |

Age is the matching factor in this nested case–control study.

Index date is the clinical diagnosis date of the case. All data for cases and controls were collected relative to this date.

This p-value derives from the conditional logistic regression analysis (Table 2).

SD, standard deviation; TPO, thyroperoxidase.

Pituitary antibodies at diagnosis are more prevalent in Hashimoto's thyroiditis than in controls

Pituitary antibodies were found at the time of clinical diagnosis in 8 of 87 (9.2%) Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases and in 3 of 107 (2.8%) controls (Table 1). Analyzing the data using a conditional logistic regression model, which takes into account the matching, revealed that pituitary antibodies increased the odds of having Hashimoto's thyroiditis by sevenfold (95% confidence interval [CI] from 1.24 to 40.1), after adjusting for race and thyroperoxidase antibodies (p=0.028, Table 2). Regression analysis also showed that, not surprisingly, thyroperoxidase antibodies strongly predicted Hashimoto's thyroiditis (Table 2): for every 10 units increase in thyroperoxidase antibody titer, the odds of having Hashimoto's thyroiditis increased 10.002-fold (95% CI: 10.001–10.003, p<0.0001). In contrast, thyroglobulin antibodies were not contributory to the diagnosis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and were, therefore, not included in the final regression model. Pituitary antibodies did not correlate with the titer of thyroperoxidase or thyroglobulin antibodies, since they were equally found in subjects with or without thyroid antibodies (Table 3).

Table 2.

Conditional Logistic Regression Analysis to Assess the Odds of Having Hashimoto's Thyroiditis Based on Pituitary Antibodies, Race, and Thyroperoxidase Antibodies in Female Active-Duty Military Personnel

| Covariate | Odds ratioa | Lower 95% CL | Upper 95% CL | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pituitary antibodies at diagnosis versus no antibodies | 7.05 | 1.24 | 40.1 | 0.028 |

| White race versus nonwhite | 2.57 | 1.08 | 6.14 | 0.034 |

| TPO antibodies at diagnosis (continuous WHO units/mL) | 1.0002 | 1.0001 | 1.0003 | <0.0001 |

Odds ratios are estimated using a conditional logistic regression model matched on age and work status and adjusted for race and TPO antibodies.

Table 3.

Key Features of the 11 Female U.S. Soldiers Who Tested Positive for Pituitary Antibodies

| Clinical diagnosis | Age | Race | Tg antibodies (WHO U/mL) | TPO antibodies (WHO U/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | 27 | Unknown | 18.2 | 2.14 |

| Healthy | 39 | White | 39.7 | 10.4 |

| Healthy | 39 | African-American | 24.5 | 42.2 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 28 | Hispanic | 12.5 | 2.5 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 36 | White | 32.4 | 9.8 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 43 | White | 15.8 | 20.1 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 25 | White | 339.9 | 24.5 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 41 | African-American | 108.4 | 28.4 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 30 | White | 25.8 | 41.1 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 35 | African-American | 119.2 | 1318.3 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 36 | Unknown | 488.6 | 1612.8 |

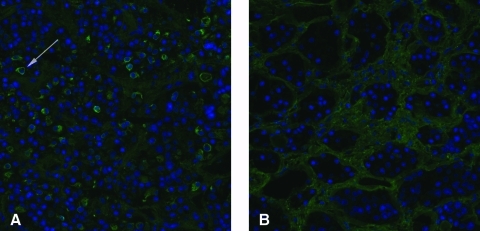

On immunofluorescence, the pattern of cytosolic positivity clustered around the periphery of the anterior pituitary cells and, combined to the negativity of the nucleus, gave to the cell the appearance of a ring (Fig. 1A, arrow). This pattern resembled the type 2 pattern reported by Bellastella and colleagues (25), although it involved only a fraction of the anterior pituitary cells. This ring pattern was similar in cases and controls. No reactivity was found against the posterior pituitary in all of the 194 subjects evaluated in this study.

FIG. 1.

Pituitary antibody immunofluorescence assay in a positive case with Hashimoto's thyroiditis (A) and in a negative control (B). The blue color identifies the nucleus of each anterior pituitary cell. The dim green highlights the connective tissue that delimitates the pituitary acini. The bright cytosolic green in (A) identifies the pituitary cells stained by the pituitary antibodies. An example of positive cell is indicated by the arrow. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/thy

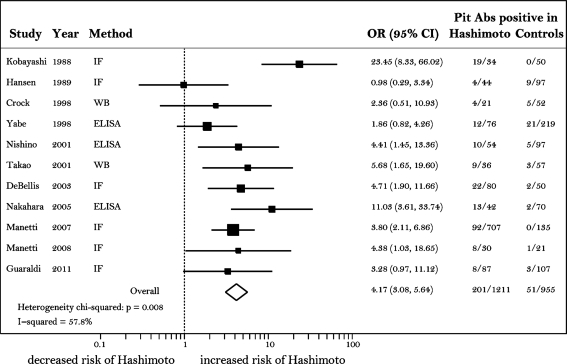

The increased frequency of pituitary antibodies in Hashimoto's thyroiditis observed in this study was in line with that reported in previous studies (Fig. 2). In particular, with the exception of the 1989 Hansen study (15), the other nine studies and the current study showed that pituitary antibodies are more common in Hashimoto's thyroiditis than in healthy controls, despite the use of different methods (immunofluorescence, western blotting, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) and protein substrates (human, monkey, and rat) (Fig. 2). The combined OR for all 11 studies (Fig. 2, diamond) was 4.2, with 95% CI ranging from 3.1 to 5.6.

FIG. 2.

Forest plot displaying the meta-analysis results of the previous 10 studies and the current study measuring the prevalence of pituitary antibodies in Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases and controls. Each study is represented by a square and a horizontal line. The square is the point estimate (the OR) and the line the CI. The area of the square reflects the weight that the study contributes to the meta-analysis. The combined-effect OR and its CI are represented by the diamond. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

When tested against a control endocrine tissue (the thyroid gland), the 11 subjects who were positive for pituitary antibodies became negative, indicating that the antibody recognition was specific for the pituitary gland (data not shown). When tested by double immunofluorescence for growth hormone, all 11 subjects did not show colocalization (data not shown), suggesting that their pituitary antibodies recognized antigens not present in the growth-hormone-producing cells. The identity of the pituitary autoantigens recognized by these antibodies remains to be discovered.

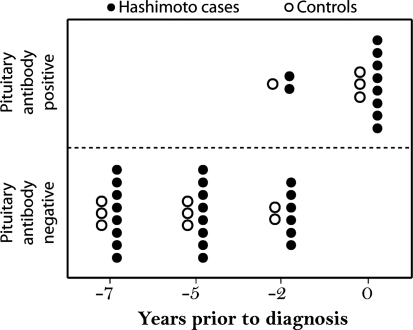

Pituitary antibodies tend to appear at the time of clinical diagnosis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis and are rarely found in prediagnostic time points

The 11 subjects (8 cases and 3 controls) who tested positive for pituitary antibodies at the time of the clinical diagnosis were also tested for the presence of pituitary antibodies in three serum specimens obtained prior to the clinical diagnosis. Only 3 of 11 subjects, 2 cases with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and 1 control, were also positive for pituitary antibodies at the −2-year time point (Fig. 3). All 11 subjects were negative at −5- and −7-year time points. Overall, these results suggest that pituitary antibodies appear near the time of the clinical diagnosis in those Hashimoto's thyroiditis patients who develop them.

FIG. 3.

Prevalence of pituitary antibody positivity in relation to the time of clinical diagnosis. Filled circles indicate cases with Hashimoto's thyroiditis; open circles indicate controls. Note that all the subjects who were pituitary antibody positive at the time of clinical diagnosis were negative at 5 and 7 years prior to diagnosis.

Discussion

This study reports that patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis are seven times more likely to have pituitary antibodies at the time of clinical diagnosis than healthy controls, thus confirming the trend revealed by most of the previous studies. When all studies are included in a meta-analysis, results indicate that the presence of pituitary antibodies increases the risk of having Hashimoto's thyroiditis by approximately fourfold. Further, this study reports for the first time that pituitary antibodies appear within two years of the clinical diagnosis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, but are absent at earlier time points.

Hashimoto's thyroiditis is known to cluster in the same patient (co-morbidity) and/or family (familial aggregation) with other autoimmune diseases (26), including autoimmune hypophysitis (8), suggesting shared genetic predisposition or environmental exposures. While the association between thyroid and pituitary autoimmunity has been described in a case report since 1962 (27) and in case–control studies since 1988 (14), the strength of this association and its significance have remained uncertain. Part of the uncertainty can be explained by the significant heterogeneity present between the studies. As indicated in Figure 2, the test for between-study heterogeneity was significant (p=0.008) and the percentage of variation attributable to between-study heterogeneity (the I-squared value) was substantial (57.8%). Removal of the Kobayshi study from the analysis, which was the one with the greatest influence on the overall meta-analysis summary estimate (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/thy), markedly reduced the between-study heterogeneity (p=0.212, I2=25.1%). Differences in the methodology that is used to detect the presence of pituitary autoimmunity are partly responsible for the observed variation. As indicated in Figure 2, of the 10 previously published studies, 5 used immunofluorescence (14,15,20,22,23), 3 used ELISA (17,18,21), and 2 used western blotting (16,19). Even within the same methodology, the substrates used for the assay were different. For example, for immunofluorescence, the authors used unfixed frozen sections of rat pituitary (14), unfixed frozen sections of baboon pituitary (20), unfixed frozen sections of Macaca mulatta pituitary (22,23), or Bouin-fixed paraffin sections of rat pituitary (15). Despite these differences, most studies conveyed the same general message that pituitary antibodies are more common in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis than in healthy controls. The only study that found no differences between patients and controls was the 1989 Hansen study that, by using Bouin-fixed tissue materials, might have resulted in the preservation of different autoantigens (15). The study subjects and the analytical methods could also represent a source of variation. For these reasons, we designed a nested case–control study where subjects were matched on age and work status, and used a multiple regression analysis to control for race and presence of thyroid autoantibodies to attenuate the source of variation due to analytical methods.

Our study also indicates that pituitary antibodies appear late in the natural history of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, perhaps implying that in this setting they are of modest clinical significance. In addition, the pattern of antibody positivity, although cytosolic, was huddled around the periphery of the anterior pituitary cells. This pattern corresponds to the type 2 pattern of Bellastella and colleagues, which has not been associated with pituitary dysfunction or progression toward hypopituitarism (25). Nevertheless, since analyses of pituitary function were not performed, the true significance of pituitary antibodies in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis remains to be ascertained.

In conclusion, pituitary antibodies are more frequent in Hashimoto's thyroiditis than in healthy controls and follow by several years the development of thyroid antibodies. Although the clinical significance remains to be determined, their detection can contribute to the understanding of disease clustering in patients with autoimmune endocrinopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Angie Eick-Cost, Special Studies Lead at the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, and Mrs. Ashley Cardamone from the Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University, for their help with the study. This work was supported by NIH grant DK080351 to P.C.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Hahsimoto H. Zur Kenntniss der lymphomatösen Veränderung der Schilddrüse (Struma lymphomatosa) Arch Clin Chir. 1912;97:219–248. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dogan M. Acikgoz E. Acikgoz M. Cesur Y. Ariyuca S. Bektas MS. The frequency of Hashimoto thyroiditis in children and the relationship between urinary iodine level and Hashimoto thyroiditis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24:75–80. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobson DL. Gange SJ. Rose NR. Graham NM. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–243. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollowell JG. Staehling NW. Flanders WD. Hannon WH. Gunter EW. Spencer CA. Braverman LE. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489–499. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staii A. Mirocha S. Todorova-Koteva K. Glinberg S. Jaume JC. Hashimoto thyroiditis is more frequent than expected when diagnosed by cytology which uncovers a pre-clinical state. Thyroid Res. 2010;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1756-6614-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitacre CC. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:777–780. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boelaert K. Newby PR. Simmonds MJ. Holder RL. Carr-Smith JD. Heward JM. Manji N. Allahabadia A. Armitage M. Chatterjee KV. Lazarus JH. Pearce SH. Vaidya B. Gough SC. Franklyn JA. Prevalence, relative risk of other autoimmune diseases in subjects with autoimmune thyroid disease. Am J Med. 2010;123:183 e181–e189. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caturegli P. Newschaffer C. Olivi A. Pomper MG. Burger PC. Rose NR. Autoimmune hypophysitis. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:599–614. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbuckle MR. McClain MT. Rubertone MV. Scofield RH. Dennis GJ. James JA. Harley JB. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1526–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutfless S. Matos P. Talor MV. Caturegli P. Rose NR. Significance of prediagnostic thyroid antibodies in women with autoimmune thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1466–E1471. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore M. Eisenman E. Fisher G. Olmsted SS. Santa PR. Zambrano JA. Monograph Series xxvii. Rand Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 2010. Harnessing full value from the DoD Serum Repository and the Defense Medical Surveillance System. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landek-Salgado MA. Leporati P. Lupi I. Geis A. Caturegli P. Growth hormone, proopiomelanocortin are targeted by autoantibodies in a patient with biopsy-proven IgG4-related hypophysitis. Pituitary. 2011 2011 Aug 23; doi: 10.1007/s11102-011-0338-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guaraldi F. Caturegli P. Salvatori R. Prevalence of antipituitary antibodies in acromegaly. Pituitary. 2011 2011 Oct 15; doi: 10.1007/s11102-011-0355-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi I. Inukai T. Takahashi M. Ishii A. Ohshima K. Mori M. Shimomura Y. Kobayashi S. Hashimoto A. Sugiura M. Anterior pituitary cell antibodies detected in Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves' disease. Endocrinol Jpn. 1988;35:705–708. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.35.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen BL. Hegedus L. Hansen GN. Hagen C. Hansen JM. Hoier-Madsen M. Pituitary-cell autoantibody diversity in sera from patients with untreated Graves' disease. Autoimmunity. 1989;5:49–57. doi: 10.3109/08916938909029142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crock PA. Cytosolic autoantigens in lymphocytic hypophysitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:609–618. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.2.4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yabe S. Kanda T. Hirokawa M. Hasumi S. Osada M. Fukumura Y. Kobayashi I. Determination of antipituitary antibody in patients with endocrine disorders by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot analysis. J Lab Clin Med. 1998;132:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishino M. Yabe S. Murakami M. Kanda T. Kobayashi I. Detection of antipituitary antibodies in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Endocr J. 2001;48:185–191. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.48.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takao T. Nanamiya W. Matsumoto R. Asaba K. Okabayashi T. Hashimoto K. Antipituitary antibodies in patients with lymphocytic hypophysitis. Horm Res. 2001;55:288–292. doi: 10.1159/000050015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bellis A. Bizzarro A. Conte M. Perrino S. Coronella C. Solimeno S. Sinisi AM. Stile LA. Pisano G. Bellastella A. Antipituitary antibodies in adults with apparently idiopathic growth hormone deficiency and in adults with autoimmune endocrine diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:650–654. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakahara R. Tsunekawa K. Yabe S. Nara M. Seki K. Kasahara T. Ogiwara T. Nishino M. Kobayashi I. Murakami M. Association of antipituitary antibody and type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase antibody in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Endocr J. 2005;52:691–699. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.52.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manetti L. Lupi I. Morselli LL. Albertini S. Cosottini M. Grasso L. Genovesi M. Pinna G. Mariotti S. Bogazzi F. Bartalena L. Martino E. Prevalence and functional significance of antipituitary antibodies in patients with autoimmune and non-autoimmune thyroid diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2176–2181. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manetti L. Parkes AB. Lupi I. Di Cianni G. Bogazzi F. Albertini S. Morselli LL. Raffaelli V. Russo D. Rossi G. Gasperi M. Lazarus JH. Martino E. Serum pituitary antibodies in normal pregnancy and in patients with postpartum thyroiditis: a nested case-control study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:805–809. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yusuf S. Peto R. Lewis J. Collins R. Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27:335–371. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellastella G. Rotondi M. Pane E. Dello Iacovo A. Pirali B. Dalla Mora L. Falorni A. Sinisi AA. Bizzarro A. Colao A. Chiovato L. De Bellis A. Predictive role of the immunostaining pattern of immunofluorescence and the titers of antipituitary antibodies at presentation for the occurrence of autoimmune hypopituitarism in patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes over a five-year follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3750–3757. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eaton WW. Rose NR. Kalaydjian A. Pedersen MG. Mortensen PB. Epidemiology of autoimmune diseases in Denmark. J Autoimmun. 2007;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goudie RB. Pinkerton PH. Anterior hypophysitis and Hashimoto's disease in a young woman. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1962;83:584–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.