Abstract

Context:

Evaluation of microhardness of root dentin provides indirect information on the change in mineral content of root dentin thereby providing useful information on the bonding quality of resin-based root canal sealers.

Aim:

This study evaluated the effect of 17% EDTA, MTAD, and 18% HEBP solutions on the microhardness of human root canal dentin using the Vickers microhardness test.

Materials and Methods:

Forty human single-rooted teeth were decoronated at the cementoenamel junction and sectioned longitudinally into buccal and lingual segments. Eighty specimens were divided into four groups (n=20). Group I was treated with distilled water (control), groups II, III, and IV were treated with 1.3% NaOCl as a working solution for 20 minutes followed by 17% EDTA, MTAD, and 18% HEBP respectively. The surface hardness of the root dentin was determined in each specimen with a Vicker's hardness tester. The values were statistically analyzed using the one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey multiple comparison tests.

Results:

There was a statistical significant difference among all the groups (one-way ANOVA; P<0.001). Among the experimental groups, HEBP showed the highest dentin microhardness (53.74 MPa, P<0.001). Least microhardness was found with MTAD (42.85 MPa, P<0.001).

Conclusions:

HEBP as a final rinse appears to be a promising irrigation protocol with less impact on the mineral content of root dentin.

Keywords: Chelating agent, ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid, HEBP, microhardness, MTAD™, sodium hypochlorite, smear layer

INTRODUCTION

The success of root canal therapy depends on the method and the quality of instrumentation, irrigation, disinfection, and three-dimensional obturation of the root canal. Endodontic instrumentation using either manual or mechanized techniques produces a smear layer and plugs of organic and inorganic particles of calcified tissue. The smear layer contains additional organic elements such as pulp tissue debris, odontoblastic processes, microorganisms, and blood cells in the dentinal tubules.[1]

A smear layer can create a space between the inner wall of the root canal and the obturating materials, thus preventing the complete locking and adherence of the root canal filling materials into the dentinal tubules.[2] It also contains bacteria and bacterial by-products and thus must be completely removed from the root canal system.[3] In addition, removal of the smear layer can allow intracanal medicaments to penetrate the dentinal tubules for better disinfection.[4]

Among the different root canal irrigants for removal of smear layer, sodium hypochlorite, (NaOCl), and ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) solution are commonly used. MTAD, containing 3% doxycycline, 4.25% citric acid, and detergent (Tween 80), has been shown to be clinically effective in removing the smear layer when used along with NaOCl.[5] However, few reports suggest that the microhardness of dentin decreases when they are exposed to NaOCl[6] or EDTA,[7] or MTAD.[8]

It has been indicated that microhardness determination can provide indirect evidence of mineral loss or gain in the dental hard tissues.[9] It has been reported that these kinds of chemical irrigants caused alterations in the chemical structure of human dentin and changed the Ca: P ratio of the dentin surface.[10] Any change in the Ca: P may change the permeability and solubility characteristics of dentin which may also affect the quality of its adhesion to root canal sealers.[11] This results in compromised sealer penetration and significant apical microleakage.[3] Moreover, EDTA and citric acid (component of MTAD) strongly reacts with sodium hypochlorite, thus rendering the latter agent ineffective.[12] Therefore it is necessary to find a new, safe, and effective irrigating regimen during root canal preparation.

A soft chelating irrigation protocol with etidronic acid, also known as 1-hydroxyethylidene-1, 1-bisphosphonate (HEBP) or etidronate, has been proposed as a potential alternative to EDTA or citric acid because of its chelating ability.[11–13] It shows no short-term reactivity with sodium hypochlorite.[12] However the effect of HEBP on microhardness of root dentin has not been evaluated so far in the literature.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of 18% HEBP solutions as a final rinse on the microhardness of human root canal dentin in comparison with 17% EDTA and MTAD using Vicker's microhardness test.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen preparation

Forty human single-rooted mandibular premolars, recently extracted for orthodontic reasons, were used for this study. The teeth were decoronated at the cementoenamel junction sectioned longitudinally starting from cervical with a low speed diamond saw (Isomet, Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, NY, USA). The separated buccal and lingual root segments were horizontally mounted in autopolymerising acrylic resin so that their dentin was exposed. The dentin surfaces of the mounted specimens were grounded smooth with a series of increasingly fine emery papers (Shor International Corporation, Mt. Vernon, NY, USA) under distilled water to remove any surface scratches, and finally polished with 0.1 μm alumina suspension (Ultra-Sol R, Eminess Technologies Inc., Monroe, NC, USA) on felt cloth.

Eighty mounted specimens were randomly divided into four groups (n=20). All the groups were treated with different irrigants as per the following protocol:[14]

Group I: The specimens were treated with distilled water (control).

Group II: The specimens were treated with 1.3% NaOCl (Prime Dental Products Ltd., Mumbai, India) for 20 minutes followed by 17% EDTA (Dent Wash Prime Dental Products Ltd., Mumbai, India) for 1 minute.

Group III: The specimens were treated with 1.3% NaOCl for 20 minutes followed by MTAD (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK, USA) for 5 minutes.

Group IV: The specimens were treated with 1.3% NaOCl for 20 minutes followed by 18% HEBP for 5 minutes.

HEBP solutions were freshly prepared by mixing the HEBP powder (Zschimmer and Schwarz Mohsdorf GmbH and Co., KG, Burgstadt, Germany) with bi-distilled water to w/v concentrations of 18%. The surface hardness of the root dentin was determined in each specimen with a Vicker's hardness tester (Matsuzawa MMT-7, Matsuzawa SEIKI Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The indentations were made with a Vicker's diamond indenter at a minimum of three widely separated locations. The locations were chosen in apical, middle, and cervical region of the root canal wall. The indentations were made on the cut surface of each specimen using 300 g load and a dwell time of 20 seconds. The values were averaged to produce one hardness value for each specimen. These measurements were converted into Vicker's numbers.

Statistical analysis

The microhardness data were tabulated and statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA and the inter group comparison of means was conducted using a post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test. Significance was established at P<0.05 level.

RESULTS

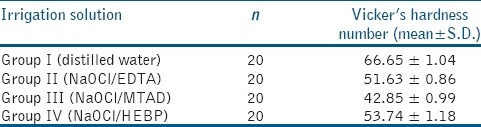

The mean and standard deviation values of the root dentin microhardness data for the control groups and 17% EDTA, MTAD, and 18% HEBP groups are listed in Table 1. The microhardness values of control (group I), EDTA treated (group II), MTAD treated (group III), and HEBP treated (group IV) groups were 66.65 ± 1.04, 51.63 ± 0.86, 42.85 ± 0.99, and 53.74 ± 1.18, respectively. The differences in microhardness were statistically significant for all the groups (P<0.001). Intergroup comparison showed that the reduction in microhardness was statistically significant among the experimental groups as well as between the experimental and control group (P<0.001).

Table 1.

The mean Vicker's hardness number value of three irrigating regimes on radicular dentin

DISCUSSION

Current concepts of chemo-mechanical preparation imply that chemicals should be applied on instrumented root canal surfaces in order to remove the smear layer following mechanical preparation.[14]

It has been proved that different irrigant activation protocols enhance the action of chelating agents.[15] But the objective of our investigation was only to assess the chemical action of chelating agent as final rinse on the microhardness of root dentin. Hence, none of the irrigant activation protocol was used in this study. The irrigating regimens in all the experimental groups were standardized to 20 minutes of 1.3% NaOCl, which represents the working solution, followed by a final rinse 17% EDTA for 1 minute in group II[16] MTAD for 5 minutes in group III[11] and 18% HEBP for 5 minutes in group IV.[11] The changes in the apatite/collagen ratio and flexural strength of mineralized dentin were also found to be insignificant with 1.3% NaOCl for 20 minutes.[17]

The process of the smear layer removal is usually more efficient in the coronal and middle third of the canals in the absence of surfactant.[18] A relatively small canal diameter in the apical one-third exposes the dentin to a lesser volume of irrigants and hence compromising the efficiency of smear layer removal.[6] Therefore tooth specimens were split longitudinally to ensure complete distribution of irrigants throughout the root canal system. The ability of Vicker's microhardness test to detect surface changes after chemical treatment with EDTA and citric acid solutions for smear layer removal has been demonstrated.[19] As microhardness of dentin may vary considerably within the same tooth,[20] three indentations were made in the cervical, middle, and apical root canal wall and the means for each sample were calculated.[19]

In our study, the microhardness of the root dentin specimens following exposure with chelating agents reduced drastically when compared with the nontreated specimens (control group). The microhardness of root dentin following MTAD as a final rinse was significantly less when compared to that of EDTA. This difference could be attributed to the increased depth of demineralization of MTAD (8–12 μm) in relation to EDTA (2–4 μm).[21] It has also been showed that MTAD and 5% citric acid had higher demineralization kinetics compared to 17% EDTA.[22]

HEBP-treated root dentin showed the highest microhardness next to the control group. This could be attributed to the larger intertubular dentin area available for hybridization when a soft chelating irrigation protocol using HEBP is applied.[23] It has been suggested that the total available area of intertubular dentin is an important aspect in the hybridization process. The major retention is provided by micromechanical interactions of the bonding agent with the collagen matrix and the underlying mineralized zone in the intertubular dentin.[24] Accordingly, HEBP increased the bond strength of resin-based sealers to root canal dentin compared with EDTA and MTAD.[11] Moreover, there is evidence that partial depletion of surface Ca++ may significantly alter the bond strength of some adhesive materials.[25]

The bonding quality of resin-based obturation material to root dentin has been evaluated following a soft chelating irrigation protocol by performing micropush-out[14] and shear bond strength assessment.[13] However, these bond strength values are useful only in indirect understanding the influence of a different irrigation protocol on dentin demineralization. The important aspect pertaining to the use of a soft chelating solution is the depth of demineralization which decides the sealing ability.[21]

CONCLUSION

Under the limitations of the study, HEBP as a final rinse appears to be a promising irrigation protocol with less impact on the mineral content of root dentin. However, further studies are required on the depth of demineralization and the sealing ability of resin-based sealers with the radicular dentin to provide more information on the clinical performance of HEBP.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sen BH, Wesselink PR, Turkun M. The smear layer: A phenomenon in root canal therapy. Int Endod J. 1995;28:141–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1995.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McComb D, Smith DC. A preliminary scanning electron microscopic study of root canals after endodontic procedures. J Endod. 1975;1:238–42. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(75)80226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pashley DH, Michelich V, Kehl T. Dentin permeability: Effects of smear layer removal. J Prosthet Dent. 1981;46:531–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(81)90243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haapasalo M, Orstavik D. In vitro infection and disinfection of dentinal tubules. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1375–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660081801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torabinejad M, Khademi AA, Babagoli J, Cho Y, Johnson WB, Bozhilov K. A new solution for the removal of the smear layer. J Endod. 2003;29:170–5. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slutzky-Goldberg I, Maree M, Liberman R, Helig I. Effect of sodium hypochlorite on dentin microhardness. J Endod. 2004;30:880–2. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000128748.05148.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Filho AM, Sousa-Neto MD, Savioli RN, Silva RG, Vansan LP, Pecora JD. Effect of chelating solutions on the microhardness of root canal lumen dentin. J Endod. 2011;37:358–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saghiri MA, Delvarani A, Mehrvazfar P, Malganji G, Lotfi M, Dadresanfar B, et al. A study of the relation between erosion and microhardness of root canal dentin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2009;108:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arends SJ, Ten Bosch JJ. Demineralization and remineralisation evaluation techniques. J Dent Res. 1992;71:924–8. doi: 10.1177/002203459207100S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennequin M, Pajot J, Avignant D. Effects of different pH values of citric acid solutions on the calcium and phosphorus contents of human root dentin. J Endod. 1994;20:551–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De-Deus G, Namen F, Galan J, Jr, Zehnder M. Soft chelating irrigation protocol optimizes bonding quality of Resilon/Epiphany root fillings. J Endod. 2008;34:703–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zehnder M, Schmidlin P, Sener B, Waltimo T. Chelation in root canal therapy reconsidered. J Endod. 2005;31:817–20. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000158233.59316.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kandaswamy D, Venkateshbabu N, Arathi G, Roohi R, Anand S. Effects of various final irrigants on the shear bond strength of resin-based sealer to dentin. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14:40–2. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.80737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopikrishna V, Venkateshbabu N, Krithikadatta J, Kandaswamy D. Evalution of the effect of MTAD in comparison with EDTA when employed as the final rinse on the shear bond strength of three endodontic sealers to dentine. Aust Endod. 2011;37:12–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2010.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caron G, Nham K, Bronnec F, Machtou P. Effectiveness of different final irrigant activation protocols on smear layer removal in curved canals. J Endod. 2010;36:1361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman LB, Bogis J, Cavlieri R, Lin PS. Scanning electron microscopic study of the effects of various irrigants and combinations on the walls of prepared root canals. J Endod. 1982;11:487–92. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(82)80073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zang K, Kim YK, Cadenaro M, Bryan TE, Sidow SJ, Loushine RJ, et al. Effects of different exposure times and concentrations of sodium hypochlorite/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid on the structural integrity of mineralized dentin. J Endod. 2010;1:105–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwanami M, Yoshioka T, Sunakawa M, Kobayashi C, Suda H. Spreading of root canal irrigants on root dentine. Aust Endod J. 2007;33:66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eldeniz AU, Erdemir A, Belli S. Effect of EDTA and citric acid solutions on the microhardness and the roughness of human root canal dentin. J Endod. 2005;31:107–10. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000136212.53475.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig RG, Gehring PE, Peyton FA. Relation of structure to the microhardness of human dentine. J Dent Res. 1959;38:624–30. doi: 10.1177/00220345590380032701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Godoy F, Loushine RJ, Itthagarun AL, Weller RN, Murray PE, Feilzer AJ, et al. Application of biologically-oriented dentin bonding principles to the use of endodontic irrigants. Am J Dent. 2005;18:281–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De-Deus G, Resi C, Fidel S, Fidel R, Paciornik S. Dentin demineralization when subjected to BioPure MTAD: A longitudinal and Quantitative Assessment. J Endod. 2007;33:1364–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De-Deus G, Zehnder M, Resi C, Fidel S, Fidel RA, Galan J Jr, et al. Longitudinal co-site optical microscopy study on the chelating ability of Etidronate and EDTA using comparative single-tooth model. J Endod. 2008;34:71–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tagami J, Tao L, Pashley DH. Correlation among dentin depth, permeability and bond strength of adhesive resins. Dent Mater. 1990;6:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(90)90044-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panighi M, G’ Sell C. Influence of calcium concentration on the dentin wettability by an adhesive. J Biomed Mat Res. 1992;26:1081–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820260809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]