Abstract

Aim:

The purpose of this in vitro study was to evaluate the ultrastructural changes of dentin induced after exposure to different intracoronal tooth bleaching agents.

Materials and Methods:

Dental discs of 1 mm thickness were prepared from coronal dentin of sixty-four human maxillary premolars. Experimental specimens were divided into four subgroups: 45% carbamide peroxide, 35% hydrogen peroxide, sodium perborate + 30% hydrogen peroxide, sodium perborate + water. The specimens were then evaluated under scanning electron microscope to determine diameter of dentinal tubules and chemical analysis.

Results:

There was significant difference between dentinal tubule diameter of all test and control groups with the exception of sodium perborate + water. Chemical analysis revealed that there was no significant difference between experimental subgroups regarding calcium and sulfur wt%.

Conclusions:

All bleaching agents increased dentinal tubule diameter and promote alterations in mineral content of dentin with the exception of Sodium perborate mixed with water.

Keywords: Bleaching, mineral content, tubule diameter

INTRODUCTION

Discoloration of non-vital teeth arises from hemorrhage caused by trauma, necrotic pulp tissue and endodontic material's remnants in the pulp chamber.

There are different peroxide releasing materials in various forms and concentrations used in both walking bleaching and thermocatalytic method for treating these problems.[1] In the walking bleaching, the most commonly used bleaching agents are hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate, either alone or in combination. The successful use of carbamide peroxide gel with different concentrations during the walking bleaching technique has also been reported in the literature.[2] Although these products are highly effective in lightening tooth color, the safety of some of these oxidizing agents is a subject for concern. Pulpal irritation, changes in the tooth structure, microleakage of restorations, reduced bond strength of composite restorations, external root resorption, and other alterations were associated with these agents.[3–7] Some researches have also shown that bleaching agents caused alterations in the chemical structure of human hard tissues. These materials changed the original ratio between the organic and inorganic components of the tissues and increased their solubility.[8] Haywood et al.[9] evaluated the effects of hydrogen peroxide released from a carbamide peroxide gel on tooth surfaces. They showed no difference in surface texture between treated and control areas using SEM analysis. A number of other SEM studies[10–15] also showed little or no topographic changes to bleached enamel. In contrast, Covington et al.[16] reported changes in surface morphology of bleached enamel. Several other studies[17,18] have reported varied morphological changes including pitting, “waviness” and increased surface roughness.

While studies on the effects of bleaching on morphological changes to dental hard tissue are contradictory, it is generally agreed that bleaching materials can alter tooth mineral contents. Potocnik and Gaspersic[19] using electron probe microanalysis demonstrated lowered concentrations of Ca and phosphorous (P) and with mean Ca/P value of all bleached samples decreasing after bleaching with 10% CP. Lee et al.[20] showed mineral loss from bovine enamel by a 30% HP solution. Al-Salehi et al.[21] also showed ion release from both enamel and dentine following bleaching with different concentration of hydrogen peroxide.

Recently, 45% carbamide peroxide has been introduced for in-office and walking bleaching. There is an absence of SEM reports of dental hard tissue alteration as a result of 45% carbamide peroxide application.

The purpose of this study was to compare the commonly used intracoronal bleaching materials with 45% carbamide peroxide regarding their effect on tubular diameter and mineral content of human dentin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of the specimens

Sixty-four human premolar teeth extracted for orthodontic reasons were used in this in-vitro study. The teeth were stored in normal saline at room temperature until required.

Occlusal surfaces were cut perpendicular to long axis of the root under water-cooling with a reciprocating diamond wire saw (precision wire diamond saw, Well, Germany)., then dental discs of 1 mm thickness were cut from remaining coronal portion after being mounted in epoxy-resin. Occlusal surfaces of specimens were polished with 800, 1200 and 2400 grits silicon carbide paper (Bisco. Inc). Then they were sectioned mesioditally into 2 halves, a mesial and a distal, with a diamond disk (Edenta AG, AU/SG, Switzerland) in such a manner that control and test fragments were obtained from the same tooth. Table 1 describes information regarding bleaching agents used in this study.

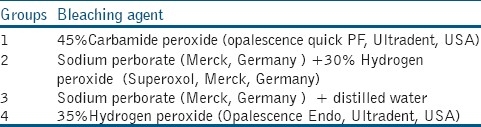

Table 1.

Bleaching agents used in each group

Bleaching procedure

Specimens in the four experimental subgroups were subjected to walking bleaching regimen as follow:

Group 1: 45%Carbamide peroxide gel was applied as a 1 mm thick layer on the polished specimens’ surface.

Group 2: A paste of sodium perborate mixed with 30% hydrogen peroxide was applied as a 1 mm thick layer on the polished specimens’ surface.

Group 3: A paste of sodium perborate mixed with distilled water was applied as a 1 mm thick layer on the polished specimens’ surface.

Group 4: 35%Carbamide peroxide gel was applied as a 1 mm thick layer on the polished specimens’ surface.

During the experimental period, old bleaching paste was cleansed by tap water, and each fresh bleaching paste was replaced 5, 10, and 15 days after the first placement. All of the specimens were stored in an environment of 37°C in 100% relative humidity for 20 days after the first placement.

Following the bleaching procedure, the specimens were ultrasonically cleaned in distilled water, air dried, mounted on aluminum stubs, gold sputter coated and then examined in a Vega II scanning electron microscope (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) using the backscattered electron mode to determine the diameter of dentinal tubules and surface histochemical analysis by energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) technique. The weight percentage of calcium, phosphorous, sulfur and potassium in the dentin of each specimen were measured.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Tukey test was done for pair-wise comparison between the means when the ANOVA was found to be significant. The significance level was set at P≤0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago II) for Windows analytical software (Microsoft, Inc. Redmond, WA, USA).

RESULTS

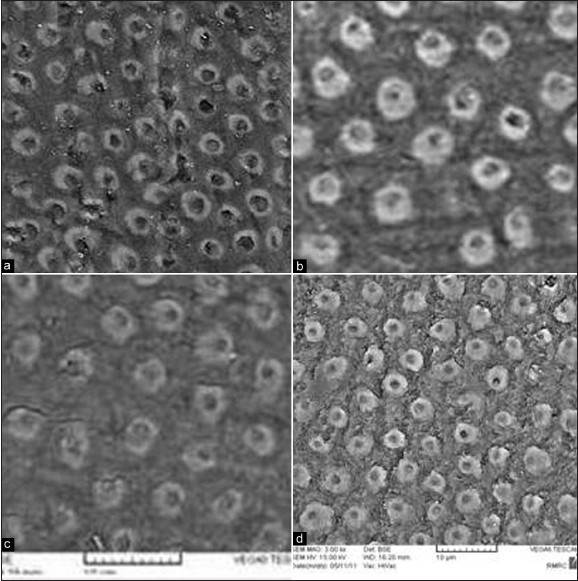

According to the SEM evaluations and statistical analyses regarding dentinal tubule diameter, there was significant difference between mean dentinal tubule diameters of all test subgroups and their corresponding control subgroups with the exception of sodium perborate mixed with water [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Electro-micrographs showed increased dentinal tubule diameter after bleaching with: (a) 45%carbamide peroxide (maximum increase), (b) sodium perborate + 30%H2O2, (c) sodium perborate + water (minimum increase), (d) 35%. H2O2

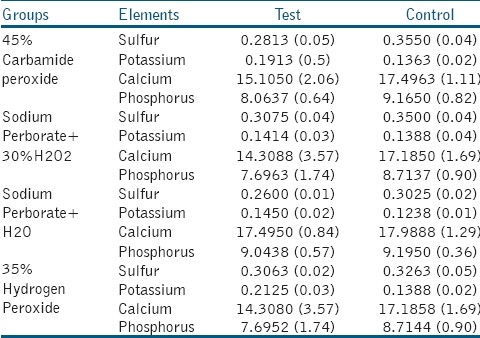

Chemical analysis revealed that there was no significant difference among control subgroups regarding mineral content but there was a significant reduction in weight percent of calcium in 35%hydrogen peroxide and Sodium perborate mixed with 30% hydrogen peroxide test subgroups and a significant reduction in phosphorus wt% in all experimental subgroups and reduction of calcium ions was consistently more than phosphorous ion except for that of sodium perborate mixed with water. A significant increase in potassium wt% has occurred after bleaching in test subgroups of 45%carbamide peroxide and 35%hydrogen peroxide; and there was a significant reduction in sulfur wt% in sodium perborate mixed with water and 45% carbamide peroxide subgroups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean (SD) of mineral content value (%)

DISCUSSION

The combined scanning electron microscope and energy-dispersive spectrometer enable simultaneous examination of tubule's diameters and organic and inorganic analysis of the specimens. The main advantage of this system is its ability to conduct an accurate and nondestructive analysis of the specimens.

According to the SEM results bleaching with all whitening agents caused a significant increase in tubule diameter with the exception of sodium perborate mixed with water. The greatest changes in tubule's diameters has been found in 45% Carbamide peroxide group in spite of the fact that its hydrogen peroxide concentration was lower than 35% hydrogen peroxide and also it showed a significant reduction in calcium content. This increase in dentinal tubule diameter might be caused by mineral loss and widening of tubule orifices as a result of oxidation of proteins.[22]

Findings of our study confirm the results of Heling et al. study who reported an increase in dentinal permeability to Streptococcus faecalis. Heling interpreted this increase in permeability as an increase in tubule diameter which has been documented directly in our study.[23]

According to the EDS, bleaching with each of four bleaching agents imparts changes in weight percent of calcium, phosphorus, potassium and sulfur of dentin. There was a reduction in Ca/P ratio in all experimental subgroups Bleaching agents can promote chemical alterations in the composition of the tooth, reducing the quantity of calcium and phosphate in enamel and dentin.[24] These elements are present in the hydroxyapatite crystals and reduction in their weight percent could be interpreted as demineralization. There was a reduction in sulfur levels and an increase in potassium in all groups. Rotstein et al.[3] studied the changes of chemical elements of teeth after bleaching with a solution of sodium perborate mixed with water, reported a significant reduction in the sulfur levels of cementum. A reduction in sulfur, a marker of proteoglycans present in the matrix of dental hard tissues, might indicate damage of the organic component of the matrix. However, calcium and phosphorus levels were maintained, indicating that the inorganic component was not affected.[3] Furthermore, some studies specified that hydrogen peroxide can change the hydroxyapatite structure, reducing the Ca/P ratio of the dental hard tissues.[3,25] Al-Salehi et al. demonstrated that calcium loss from enamel and dentine was more than that of phosphorous at all concentrations which effectively will reduce Ca/P ratio in the bleached samples.[21] A decrease in Ca/P ratio in bleached samples was also reported by other workers.[19,20]

Tanaka et al. reported that despite hydrogen peroxide penetrates to the mineralized tissues; carbamide peroxide decomposes to its components on the surface of tooth hard tissues and causes more surface demineralization.[26] Recently Chng et al used AFM and showed significant alterations in intertubular dentin, which were not evident in peritubular dentin indicates ultrastructural differences of these two structures.[27]

Mineral loss and increased tubular diameter can act as predisposing factors of cervical root resorption. Many researchers have reported that external cervical root resorption after intracoronal bleaching of discolored pulpless teeth has been associated with the use of highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide.[28,29] It was considered that, during bleaching, hydrogen peroxide diffused through the radicular dentin, particularly in the presence of cementum defects, to the surrounding periodontal tissues. External resorption may result either from an initiation of the inflammatory response caused by peroxides or from a secondary bacterial infection originating in patent dentinal tubules.[30] To avoid such a result, many researchers proposed that the use of hydrogen peroxide for intracoronal bleaching purpose should be avoided and protection of cervical and periodontal tissues must be emphasized in bleaching treatments.[31,32] Accordingly, 45% Carbamide peroxide is not a harmless material for intracoronal bleaching process.

CONCLUSION

Within the limits of this in vitro study, it can be concluded that: All intracoronal bleaching agents increased dentinal tubule diameter and promote alterations in organic and inorganic components of dentin with the exception of sodium perborate mixed with water. It is thought that sodium perborate does not need to be combined with 30% hydrogen peroxide solution.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Summit JB, Robbins JW, Hilton TJ, Schwartz RS, Santos JD. Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry: A Contemporary Approach. 3rd ed. Chicago: Quintessence Pub; 2006. pp. 437–63. Chapter 15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Oliviera DP, Teixeira EC, Ferraz CC, Teixeira FB. Effect of intracoronal bleaching agents on dentin microhardness. J Endod. 2007;33:460–2. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotstein I, Dankner E, Goldman A, Heling I, Stabholz A, Zalkind M. Histochemical Analysis of Dental Hard tissues following bleaching. J Endod. 1996;22:23–5. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(96)80231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tredwin CJ, Naik S, Lewis NJ, Scully C. Hydrogen peroxide tooth-whitening (bleaching) products: Review of adverse effects and safety issues. Br Dent J. 2006;200:371–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotstein I, Lehr Z, Gedalia I. Effect of Bleaching agent on inorganic components of human dentin and enamel. J Endod. 1992;18:290–3. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)80956-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crim GA. Post-operative bleaching: Effect on microleakage. Am J Dent. 1992;5:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heithersay GS. Invasive cervical resorption: An analysis of potential predisposing factors. Quintessence Int. 1999;30:83–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaves MG, Oliveira M, Pereira MN, Soares MR, Chaves Filho HD, Leite FP. Effects of external bleaching agents on dental tissues and cement-enamel junction. Dent Mater. 2010;26(Supplement 1):e67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haywood VB, Leech T, Heymann HO, Crumpler D, Bruggers K. Nightguard vital bleaching: Effects on enamel surface texture and diffusion. Quintessence Int. 1990;21:801–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst CP, Marroquin BB, Willershausen-Zonnchen B. Effects of hydrogen peroxide containing bleaching agents on the morphology of human enamel. Quintessence Int. 1996;27:53–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haywood VB, Heymann HO. Nightguard vital bleaching: How safe is it? Quintessence Int. 1991;22:515–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zalkind M, Arwaz J, Goldman A, Rotstein I. Surface morphology changes in human enamel, dentin and cementum following bleaching: A scanning electron microscopy study. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1996;12:82–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1996.tb00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oltu U, Gurgan S. Effects of three concentrations of carbamide peroxide on the structure of enamel. J Oral Rehabil. 2000;27:332–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2000.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonard JR, Eagle JC, Garland GE, Matthews KP, Rudd AL. Nightguard vital bleaching and its effects on enamel surface morphology. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2001;13:132–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2001.tb00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotz H, Duschner H, White DJ, Klukowska MA. Effects of elevated hydrogen peroxide ‘strip’ bleaching on surface and subsurface enamel including surface histomorphology, micro-chemical composition and fluorescence changes. J Dent. 2007;35:457–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covington JS, Friend GW, Lamoreaux WJ, Perry T. Carbamide peroxide tooth bleaching: Effects on enamel composition and topography. J Dent Res. 1990 Abstract 530(69:175) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon H, Spencer P, Gross K, Tira D. Characterization of enamel exposed to 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching agents. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Titley K, Torneck CD, Smith D. The effect of concentrated hydrogen peroxide solutions on the surface morphology of human tooth enamel. J Endod. 1988;14:69–74. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(88)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potocnik IK, Gaspersic D. Effect of 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching gel on ebamel microhardness. J Endod. 2000;26:203–6. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee K, Kim H, Kim K, Kwon Y. Mineral loss from bovine enamel by a 30% hydrogen peroxide solution. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33:229–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Salehi SK, Wood DJ, Hatton PV. The effect of 24h non-stop hydrogen peroxide concentration on bovine enamel and dentin mineral content and microhardness. J Dent. 2007;35:845–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin-Biedman B, Gonzalez-Gonzalez T, Lopes M, Lopes L, Vilar R, Babillo J, et al. Colorimeter and scanning electron microscopy analysis of teeth submitted to internal bleaching. J Endod. 2010;36:334–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heling I, Alex Parson MS, Rotstein I. Effect of bleaching agents on dentin permeability to Streptococcus faecalis. J Endod. 1995;21:540–2. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80981-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawamoto K, Tsujimoto Y. Efficacy of hydroxyl radical and hydrogen peroxide on tooth bleaching. J Endod. 2004;30:45–50. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bistey T, Nagy IP, Simo´ A, Hegedus C. In vitro FT-IR study of the effects of hydrogen peroxide on superficial tooth enamel. J Dent. 2007;35:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka R, Shibota Y, Manabe A, Miyazaki T. Micro-structural integrity of dental enamel subjected two tooth whitening regimes. Archs Oral Biol. 2010;55:300–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chng HK, Ramli HN, Yap AU, Lim CT. Effect of hydrogen peroxide on intertubular dentine. J Dent. 2005;33:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington GW, Natkin E. External resorption associated with bleaching of pulpless teeth. J Endod. 1979;5:344–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(79)80091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heller D, Skriber J, Lin LM. Effect of intracoronal bleaching on external cervical root resorption. J Endod. 1992;18:145–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81407-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powell LV, Bales DJ. Tooth bleaching: Its effect on oral tissues. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:50–4. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1991.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cvek M, Lindvall AM. External root resorption following bleaching of pulpless teeth with oxygen peroxide. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1985;1:56–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1985.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewinstein I, Hirschfeld 2nd, Stabholz A, Rotstein I. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate on the microhardness of human enamel and dentin. J Endod. 1994;20:61–3. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]