Abstract

Aim:

The aim is to review and discuss the strategies available for the regeneration of tooth tissues based on principles of tissue engineering.

Background:

Tissue engineering is a multidisciplinary approach that aims to regenerate functional tooth-tissue structure based on the interplay of three basic key elements: Stem cells, morphogens and scaffolds. A number of recent clinical case reports have revealed the possibilities that many teeth that traditionally would be treated byapexification may be treated by apexogenesis.

Materials and Methods:

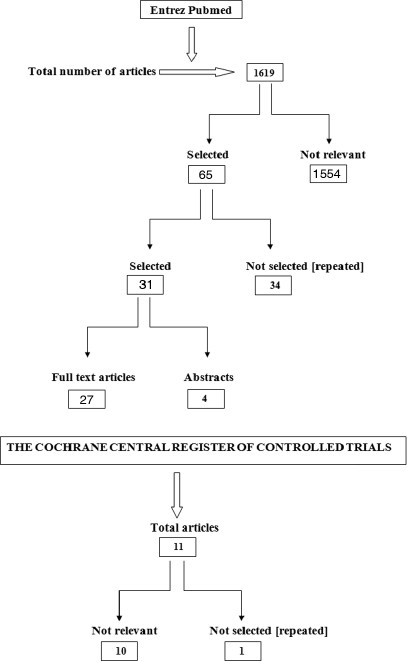

Electronic and hand search of scientific papers were carried out on the Entrez Pubmed, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases using specific keywords. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were predetermined. The search yielded 1619 papers; out of which 65 were identified as conforming to the predetermined inclusion criteria and the remaining 1554 were excluded. Out of 65 papers, 34 papers were excluded again as different key words led to the same publications. Only 31 papers were selected, out of which 27 full-text papers were found and 4 papers were included based on only the abstracts. These 31 papers formed the basis of this review. The data were extracted from the selected studies. The data were synthesized by pooling the extracted data.

Conclusion:

The field of tissue engineering has recently shown promising results and is a good prospect in dentistry for the development of the ideal restorations to replace the lost tooth structure.

Keywords: Immature permanent tooth, pulp regeneration, pulp revascularization, pulp necrosis

INTRODUCTION

The most common cause of pulp necrosis in an immature tooth is caries or trauma which arrests further root development. These immature, necrotic, permanent teeth with open apex and thin, fragile walls are difficult to treat endodontically.[1–5] The traditional treatment involves inducing an apical barrier (apexification) with calcium hydroxide or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA). These procedures do not strengthen the walls. The long-term calcium hydroxide therapy for apexification may further weaken the thin walls and leave the teeth even more prone to fracture. Root wall strengthening with composite limits the possibility of root canal retreatment if need arises in future.[3,4]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Structured electronic search of scientific papers published up to August 2011 was carried out on the Entrez Pubmed, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases using combination of the following specific keywords: Pulp regeneration, pulp revascularization, pulp necrosis, immature permanent tooth, tissue engineering, pulp vitality and regenerated dentin. The electronic search was supplemented by hand-searching through the following journals: Journal of Endodontics, International Endodontic Journal, Dental Traumatology, Pediatric Dentistry, American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, and Advanced Dental Research. The inclusion criteria set for this review were: Case reports and case series on regeneration potential of pulp-dentin complex in necrotic, immature, permanent teeth, studies evaluated pulp vitality, studies evaluated any discoloration of teeth, studies evaluated radiographical and/or histological outcomes, and studies done on healthy animal models. Exclusion criteria consisted of studies that did not meet the above inclusion criteria. Studies that did not evaluate regeneration potential of pulp-dentin complex, radiographical and/or histological evaluation of treatment outcome, pulp vitality in necrotic, immature, permanent teeth and review papers were excluded.

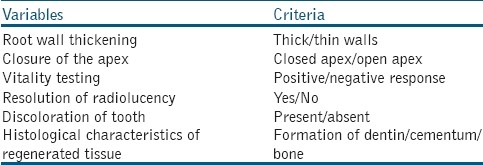

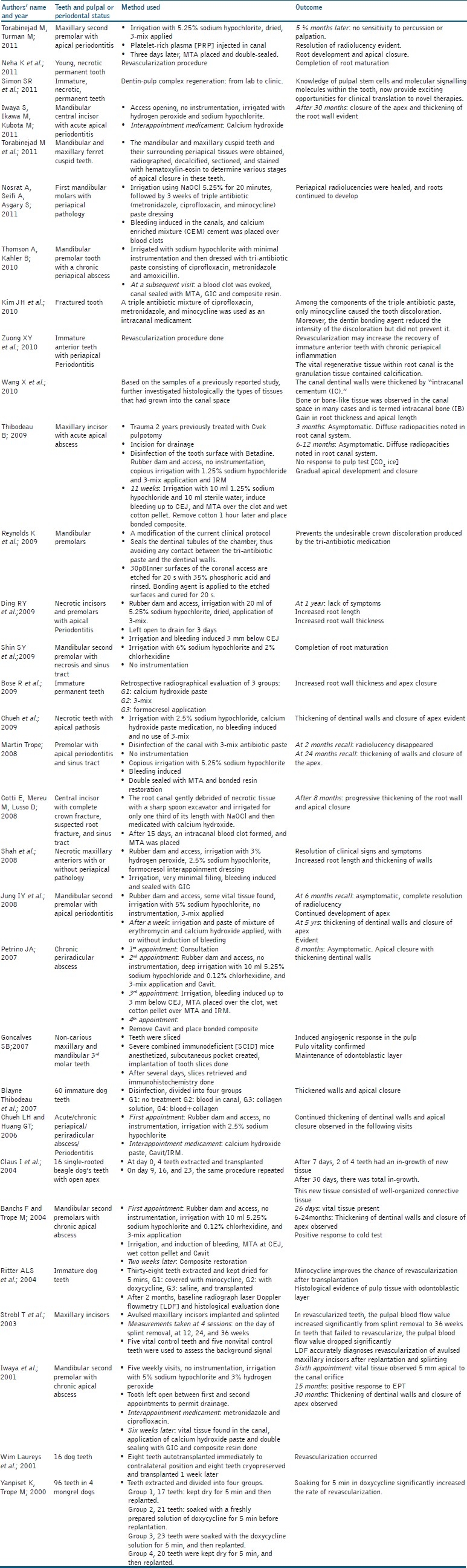

The search yielded 1619 papers; out of which 65 were identified as conforming to the predetermined inclusion criteria and the remaining 1554 were excluded. Out of 65 papers, 34 papers were excluded again as different key words led to the same publications. Only 31 papers selected, out of which 27 full-text papers were found and 4 papers were included based on only the abstracts. These 31 papers formed the basis of this review. Of the papers were selected, the data extracted were: Evaluation of increase in the thickness of the root walls and apex closure, evaluation of pulp vitality, evaluation of resolution of radiolucency, evaluation of discoloration of teeth, and evaluation of the histological characteristics of regenerated tissues [Table 1]. The following data were synthesized: Continued root growth, positive or negative response to pulp vitality testing, resolution of radiolucency, discoloration of teeth following 3-mix antibiotic paste application, and histological characteristics of regenerated tissue as dentin, cementum, or bone. The selected 31 studies have been evaluated in detail in the study characteristics table [Table 2] [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Evaluated outcome measures in various studies

Table 2.

Study characteristics

Figure 1.

Search flowchart

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Among the included papers, the case reports and case series have described the outcomes of treatment in patients who presented with immature permanent teeth with apical pathosis with or without associated sinus tract.[1–15] Some of these cases were associated with a dens evaginatus, where the thin occlusal tubercle often fractures, predisposing the tooth to bacterial infection and pulpal necrosis as often seen in mandibular premolars.[3,7,10] The outcome of previous case reports and series[1–14] indicated that it is possible to treat the necrotic and immature permanent tooth, leading to clinically symptom-free tooth, and radiographical evidence of resolution of apical periodontitis,[1–14] and continuing increase in the thickness of dentinal walls,[1–10,16–29] and apicalclosure[1–10,16–29] or further development of root length. Tables 1 and 2 show the various outcome measures evaluated across the various studies. This biological result is remarkable, given the typically poor prognosis of these cases. After analyzing these case reports and series, it is understood that the following endodontic protocols had been followed for the treatment of necrotic immature permanent teeth. The procedure had been done in two to three visits.

In the first visit, disinfection of the root canal system had been carried out. This is considered the vital step for the success of the regeneration procedure. Local anesthesia was administered. Tooth to be treated was isolated with rubber dam. The tooth was disinfected using betadine (10% Povidone Iodine Topical Solution).[16] Access was gained and drainage of pus was done if present. Working length was determined with radiograph (2-3 mm short of the apex). No instrumentation was done but instead the canal was copiously irrigated with 20 ml of 1.25% to 5.25% NaOCl, saline and 2% chlorhexidine.[1–11,16–19] An effort was made to stay within the confines of the root canal. The root canal was dried using sterile paper points. A creamy paste of equal proportions of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin and minocycline (triple antibiotic paste)[1–11,16–19] was placed in the root canal using a lentulo spiral in a slow speed handpiece or a reamer. Alternatively a combination of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin and cefaclor was used to overcome the discoloration due to minocycline. Access cavity was sealed with cotton pellets and Intermediate Restorative Material (IRM). Patient was reviewed after 2-3 weeks. Alternatively, some studies have used formocresol, calcium hydroxide instead of antibiotic paste for disinfection of the root canal system.

In the second visit, under local anesthesia without vasoconstrictor (facilitates bleeding) and rubber dam isolation, disinfection with betadine, the tooth was re-entered. The antibiotic paste was removed (and replaced if necessary) using 20 ml of 1.25-/5.25% NaOCl, saline and 2% chlorhexidine and dried to make space for a blood clot. No instrumentation of the canal was performed. The apical tissues beyond the confines of the root canal were stimulated with a sterile endodontic file or reamer or aesthetic needle to induce bleeding into the canal space. Approximately 15 minutes were allowed for the blood clot to reach a level that approximated the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). White MTA (preferably to avoid discoloration of the crown) or grey MTA was applied over the blood clot. A cotton pellet moistened with sterile water was placed over the MTA and the access was temporarily sealed with IRM. After 24 hours, the access cavity was sealed with GIC and composite. However, some studies have not used MTA. Instead, the access opening was sealed with GIC extending 4 mm into the coronal portion of the root canal and showed similar results.[9] The procedure had also been done using different matrices like Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP)[20] instead of inducing blood clot as a matrix. The patient was reviewed every 3 months to monitor for the development of root and closure of the apex till it was accomplished.

The use of the 3 Mix-MP triple antibiotic paste was developed by Hoshino and colleagues.[19] It consists of ciprofloxin, metronidazole, and minocycline. It is effective for disinfection of the infected necrotic tooth, setting conditions for the subsequent revascularization of the tooth. This triple antibiotic mixture has high efficacy. In a preclinical study on dogs, the intracanal delivery of a 20-mg/mL solution of these three antibiotics via a lentulo spiral resulted in greater than 99% reduction in mean colony-forming unit (CFU) levels.[2] The only disadvantage with 3-mix is the coronal discoloration caused by minocycline.[14] Sealing the dentinal tubules of the chamber prevents the undesirable crown discoloration produced by tri-antibiotic medication (minocycline) whilst maintaining the revascularization potential of the pulp.[19] The novel approach seals the dentinal tubules of the chamber, thus avoiding any contact between the tri-antibiotic paste and the dentinal walls. The inner surfaces of the coronal access are etched for 20 s with 35% phosphoric acid and rinsed. Bonding agent is applied to the etched surfaces and cured for 20 s. Then, a Root Canal Projector with a size 20 K-file inside the projector is placed into the prepared access to maintain patency. The space between the projector and the coronal dentine is sealed with flowable composite and light-cured for 30 s. The projector is then removed by engaging it with a Hedstrom file. If crown discoloration occurs, treatment by intracoronal bleaching with sodium perborate should be attempted. In addition, the use of white MTA instead of grey MTA should also be considered. The modified protocol described is an attempt to avoid the undesired crown discoloration. A safer and more reliable technique for antibiotic dressing is using a 20G needle with a backfill approach.[19] This novel approach prevents the undesirable crown discoloration produced by the tri-antibiotic medication.

In non-vital teeth treatment was administered with evoking of an intracanal blood clot. The initiation of blood clot is thought to provide a fibrin scaffold with platelet-derived growth factors that promotes regeneration of tissue within the root canal system. Whereas, in partially vital teeth treatment was administered without an attempt to trigger bleeding and the formation of an intracanal blood clot. Claus I et al.[24] and Ritter ALS[22] have described histological findings of the regenerated tissues. Histological findings of the new tissues showed a well-vascularized, cell-rich connective tissue. Ritter ALS and Strobl H[23] conducted studies to evaluate the efficacy of Laser Doppler Flowmetry (LDF) in diagnosing revascularization of avulsed permanent maxillary central incisors after replantation and splinting. The data indicate that an accurate LDF reading can be established at the 12-week follow-up appointment, which is much earlier than would be expected from standard sensitivity tests.[21,23]

This revascularization procedure induces root maturation. This can be a better alternative to conventional calcium hydroxide apexification. The crucial step for revascularization is disinfection of the necrotic root canal system. This can be achieved with combination of antibiotics.[1,2,6] In addition, the remaining dental pulp stem cells in the apical papilla (SCAP)[5–7,10–11,16–18] play a vital role in successful revascularization. These stem cells in the apical papilla can survive pulp necrosis because of its abundant blood supply. There are case reports based on the concept that revascularization is possible in a partially necrotic tooth.[7–9] The stem cells in the apical papilla differentiate into secondary odontoblasts to deposit dentin and help in root maturation. Most case reports have followed the protocol of no canal instrumentation to preserve these vital stem cells.[1–8,19]

The limitation of the revascularization procedure is that there is no human histological evaluation following the procedure.[24,28] Radiographical evaluation has been reported on human case series while histological evaluation has only been reported in animal studies.[22–24,28] Both these evaluations of recent reports have shown evidence of successful revascularization. In addition, there are successful reports of revascularization in teeth after replantation.[22,30] In this case, the necrotic, but, uninfected pulp in an avulsed tooth acts as a scaffold permitting growth of tissue from the periapical tissue. Ingrowth of tissue occurs easily in teeth with open apex and short root length. However, calcification of the canal can occur which makes the tooth difficult to treat endodontically in future, if required.

In 1960s, Nygaard-Ostby and Hjortdal attempted revascularization. This was in a necrotic, infected tooth with apical periodontitis, but it was unsuccessful. This could be attributed to the limited number of instruments and materials available about 50 years back. With currently available technology, it could be possible to effectively disinfect an infected pulp space and apply the scientific tissue engineering principle to regenerate the tissue.

The case reports and case series clearly demonstrate that under certain circumstances, teeth with necrotic pulps and open apices are capable of regenerating tissues within the root canals that cause continued hard tissue deposition, root lengthening, closure of the apices, and responding to cold, EPT and/or LDF. There are animal histological evaluations of the new tissues which conform that the tissues are dentin or cementum, or bone [Table 2].[21,28] Since, these procedure results in restoration of some of the functional properties of involved teeth, it is appropriate to identify this technique as regeneration of pulp-dentin complex and restrict the use of the term revascularization. Based on the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Resources [Yale University], all case reports, case series score the evidence level of 4 and the animal studies score the evidence level of 5. Despite the low level of evidence, these reports that are actual observations in patients can be the basis for future studies at higher levels of evidence.

We are now at a stage in which engineering a complex tissue, such as the dental pulp, is no longer an unachievable dream[31,32] Rather, we see tissues that look and behave very much like a human dental pulp being engineered in laboratories throughout the world. Collectively, there has been a tremendous increase in our clinical tools (i.e., materials, instruments and medications). Moreover, recent case reports from multiple investigators support the feasibility of developing biologically based regenerative endodontic procedures designed to restore a functional pulp-dentin complex. In short, the question is no longer “can regenerative endodontic procedures be successful?” Instead, the important question facing us is “what are the issues that must be addressed to develop a safe, effective, and consistent method for regenerating a functional pulp-dentin complex in our patients?”

This review shows that there are promising clinical and radiographical results on human subjects and histological results on animal studies. Based on current trends, it can be concluded that the pulp-dentin complex has the potential to regenerate in necrotic, immature, permanent teeth. However, studies with higher levels of evidence are needed to confirm the findings.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trope M. Regenerative potential of dental pulp. J Endod. 2008;34:S13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hargreaves KM, Geisler T, Henry M, Wang Y. Regeneration potential of the young permanent tooth: What does the future hold? J Endod. 2008;34:S51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwaya SI, Ikawa M, Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:185–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.017004185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banchs F, Trope M. Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: New treatment protocol? J Endod. 2004;30:196–200. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chueh LH, Huang GT. Immature teeth with periradicular perodontitis or abscess undergoing apexogenesis: A paradigm shift. J Endod. 2006;32:1205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thibodeau B. Case Report: Pulp revascularization of a necrotic, infected, immature, permanent tooth. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding RY, Cheung GS, Chen J, Yin XZ, Wang QQ, Zhang CF. Pulp revascularization of immature teeth with apical periodontitis: A clinical study. J Endod. 2009;35:745–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goncalves SB, Dong Z, Bramante CM, Holland GR, Smith AJ, Nor JE. Tooth slice-based models for the study of human dental pulp angiogenesis. J Endod. 2007;33:811–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah N, Logani A, Bhaskar U, Aggarwal V. Efficacy of revascularization to induce apexification/apexogenesis in infected, non vital, immature teeth: A pilot clinical study. J Endod. 2008;34:919–25. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung IY, Lee SJ, Hargreaves KM. Biologically based treatment of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: A case series. J Endod. 2008;34:876–87. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chueh LH, Ho YC, Kue TC, Lai WH, Chen YH, Chiang CP. Regenerative endodontic treatment for necrotic immature permanent teeth. J Endod. 2009;35:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nosrat A, Seifi A, Asgary S. Regenerative endodontic treatment (revascularization) for necrotic immature permanent molars: A review and report of two cases with a new biomaterial. J Endod. 2011;37:562–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwaya S, Ikawa M, Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with periradicular abscess after luxation. Dent Traumatol. 2011;27:55–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2010.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JH, Kim Y, Shin SJ, Park JW, Jung IY. Tooth discoloration of immature permanent incisor associated with triple antibiotic therapy: A case report. J Endod. 2010;36:1086–91. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuong XY, Yang YP, Chen WX, Zhang YJ, Wen CM. Pulp revascularization of immature anterior teeth with apical Periodontitis. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010;28:672–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thibodeau B, Teixeira F, Yamauchi M, Caplan DJ, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2007;33:680–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin SY, Albert JS, Mortman RE. One step pulp revascularization treatment of an immature permanent tooth with chronic apical abscess: A case report. Int Endod J. 2009;42:1118–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laureys W, Beele H, Cornelissen R, Dermaut L. Revascularization after cryopreservation and autotransplantation of immature and mature apicoectomized teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofaci Orthop. 2001;119:346–52. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.113259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds K, Johnson JD, Cohenca N. Pulp revascularization of necrotic bilateral bicuspids using a modified novel technique to eliminate potential coronal discolouration: A case report. Int Endod J. 2009;42:84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torabinejad M, Turman M. Revitalization of tooth with necrotic pulp and open apex by using platelet-rich plasma: A case report. J Endod. 2011;37:265–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bose R, Nummikoski P, Hargreaves K. A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. J Endod. 2009;35:1343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritter AL, Ritter AV, Murrah V, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of replanted immature dog teeth after treatment with minocycline and doxycycline assessed by laser doppler flowmetry, radiography, and histology. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-4469.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strobl H, Gojer G, Norer B, Emshoff R. Assessing revascularization of avulsed permanent maxillary incisors by laser Doppler flowmetry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1597–603. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claus I, Laureys W, Cornelissen R, Dermaut LR. Histologic Analysis of Pulpal revascularization of autotransplanted immature teeth after removal of the original pulp tissue. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2004;125:93–9. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrino JA. Revascularization of necrotic pulp of immature teeth with apical periodontitis. Northwest Dent. 2007;86:33–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torabinejad M, Corr R, Buhrley M, Wright K, Shabahang S. An animal model to study regenerative endodontics. J Endod. 2011;37:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson A, Kahler B. Regenerative endodontics--biologically-based treatment for immature permanent teeth: A case report and review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:446–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Thibodeau B, Trope M, Lin LM, Huang GT. Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2010;36:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cotti E, Mereu M, Lusso D. Regenerative treatment of an immature, traumatized tooth with apical periodontitis: Report of a case. J Endod. 2008;34:611–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanpiset K, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth after different treatment methods. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2002;16:211–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2000.016005211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neha K, Kansal R, Garg P, Joshi R, Garg D, Grover HS. Management of immature teeth by dentin-pulp regeneration: A recent approach. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e997–1004. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon SR, Berdal A, Cooper PR, Lumley PJ, Tomson PL, Smith AJ. Dentin-pulp complex regeneration: From lab to clinic. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:340–5. doi: 10.1177/0022034511405327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]