Abstract

Fbxw7α is a member of the F-box family of proteins, which function as the substrate-targeting subunits of SCF (Skp1/Cul1/F-box protein) ubiquitin ligase complexes. Using differential purifications and mass spectrometry, we identified p100, an inhibitor of NF-κB signalling, as an interactor of Fbxw7α. p100 is constitutively targeted in the nucleus for proteasomal degradation by Fbxw7α, which recognizes a conserved motif phosphorylated by GSK3. Efficient activation of non-canonical NF-κB signalling is dependent on the elimination of nuclear p100 through either degradation by Fbxw7α or exclusion by a newly identified nuclear export signal in the carboxy terminus of p100. Expression of a stable p100 mutant, expression of a constitutively nuclear p100 mutant, Fbxw7α silencing or inhibition of GSK3 in multiple myeloma cells with constitutive non-canonical NF-κB activity results in apoptosis both in cell systems and xenotransplant models. Thus, in multiple myeloma, Fbxw7α and GSK3 function as pro-survival factors through the control of p100 degradation.

Fbxw7 (F-box/WD40 repeat-containing protein 7; also known as Fbw7, hCdc4 and hSel10) is a member of the F-box family of proteins, which function as the substrate-targeting subunits of SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes1–3. Fbxw7 is an essential gene owing to its function in development and differentiation4–7. Mammals express three alternatively spliced Fbxw7 isoforms (Fbxw7α, Fbxw7β and Fbxw7γ) that are localized in the nucleus, cytoplasm and nucleolus, respectively5. The SCFFbxw7 complex targets multiple substrates, including cyclin E, c-Myc, Jun, Mcl1 and Notch (refs 5,7–9). In T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL), Fbxw7 is a tumour suppressor, and mutations in the FBXW7 gene, as well as overexpression of microRNAs targeting its expression, have been reported7,10,11. Moreover, mutations of FBXW7 have been found in a variety of solid tumours5. Interestingly, alterations of the FBXW7 gene have not been observed in multiple myelomas and B-cell lymphomas12,13.

The p100 protein belongs to the NF-κB family, which consists of five evolutionarily conserved and structurally related activator proteins (RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel (Rel), p50 and p52) and five inhibitory proteins (p100, p105 and the IκB proteins IκBα, IκBβ and IκBε). The NF-κB activators share a 300-amino-acid Rel homology domain (RHD) that controls DNA binding, dimerization and nuclear localization14. The five inhibitors are characterized by ankyrin repeat domains (ARDs) that bind the RHDs of NF-κB members to inhibit their activity, primarily by sequestering them in the cytoplasm.

p100 is the main inhibitor of the non-canonical, or alternative, NF-κB pathway15. In response to developmental signals, such as lymphotoxin (LTα1β2), B-cell activating factor (BAFF) and CD40 ligand15–20, p100 is dissociated from NF-κB dimers (p50:RelA), allowing their nuclear translocation21. Subsequent activation of the transcriptional response includes de novo synthesis of p100 (NFKB2 gene), leading to concomitant generation of p52 through a co-translational processing mechanism that requires IKKα-dependent phosphorylation of p100 on Ser 866 and Ser 870, and the activity of SCFβTrCP (refs 22–24). p52 preferentially binds RelB to activate a distinct set of gene targets involved in lymphoid development25,26. Whether and how p100 is regulated by protein degradation have not been investigated.

Constitutive activation of NF-κB is common in B-cell neoplasms27. Notably, many mutations in genes encoding regulators of non-canonical NF-κB activity have been identified in human multiple myelomas28,29 (for example, loss-of-function mutations in TRAF2/3 and cIAP1/2, gain-of-function mutations in NIK and C-terminal truncations of p100)13,28–30. These abnormalities result in a constitutively elevated level of NF-κB signalling, which is associated with glucocorticoid resistance and proteasome inhibitor sensitivity. The efficacy of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients and human multiple myeloma cell lines (HMMCLs) with inactivation of TRAF3 has been attributed in part to inhibition of the NF-κB pathway29.

Here, we show that Fbxw7α constitutively targets nuclear p100 for proteasomal degradation on phosphorylation of p100 by GSK3. Clearance of p100 from the nucleus is required for efficient activation of the NF-κB pathway and the survival of multiple myeloma cells.

RESULTS

Phosphorylation- and GSK3-dependent interaction of p100 with Fbxw7α

To identify previously unknown substrates of the SCFFbxw7α ubiquitin ligase, FLAG–HA-tagged Fbxw7α was immunopurified from HEK293 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1a) and analysed by mass spectrometry. As a negative control, we used FLAG–HA-tagged Fbxw7α (WD40), a mutant that lacks the ability to bind substrates, but not Skp1 and Cul1 (ref. 31 and Supplementary Fig. S1b). p100 peptides were identified in Fbxw7α immunoprecipitates, but not in Fbxw7α(WD40) purifications (Supplementary Fig. S1c), indicating that p100 may be a SCFFbxw7α substrate.

To investigate whether the binding between p100 and Fbxw7α is specific, we screened a panel of human WD40 domain-containing F-box proteins, as well as Cdh1 and Cdc20 (WD40 domain-containing subunits of an SCF-like ubiquitin ligase). Whereas p100, p105 and IκBα were detected in βTrCP immunoprecipitates, as previously reported24,32, Fbxw7α co-immunoprecipitated only p100 (Fig. 1a).

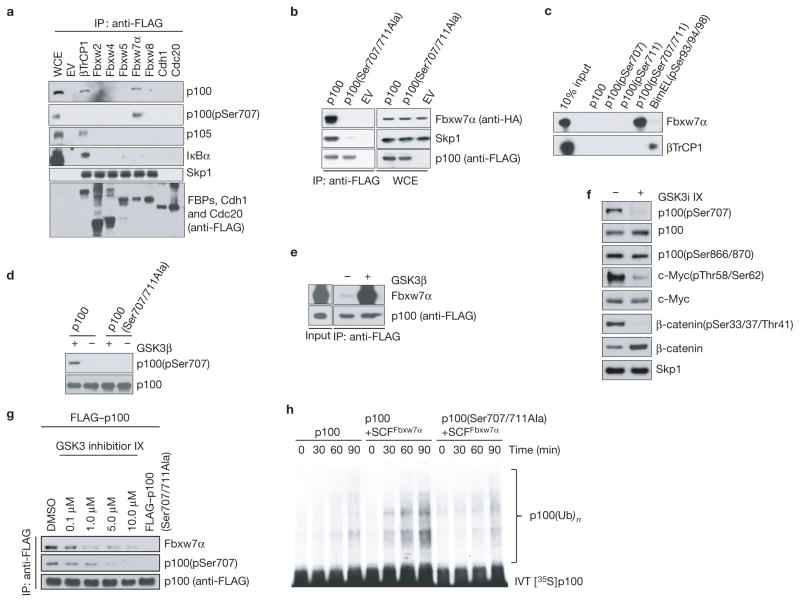

Figure 1.

p100 interacts with Fbxw7α through a conserved degron phosphorylated by GSK3. (a) p100 binds Fbxw7α. HEK293 cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding the indicated FLAG-tagged F-box proteins (FBPs), Cdh1 or Cdc20 and treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 6 h. FLAG-tagged immunoprecipitates (IPs) from cell extracts with anti-FLAG resin were immunoblotted as indicated. Lane 1 shows whole-cell extract (WCE) from empty vector (EV)-transfected cells. (b) Ser 707 and Ser 711 in p100 are required for the interaction with Fbxw7α. HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-tagged Fbxw7α and constructs encoding FLAG-tagged p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala). FLAG-tagged p100 was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts, followed by immunoblotting as indicated. The right panel shows whole-cell extract. (c) The p100 degron requires phosphorylation to bind Fbxw7α. In vitro-translated Fbxw7α and βTrCP1 were incubated with beads coupled to the indicated p100 peptides or BimEL peptide. Beads were washed and eluted proteins were immunoblotted as indicated. The first lane shows 10% of in vitro-translated protein inputs. (d) GSK3 phosphorylates p100 in vitro. In vitro-translated p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala) was incubated at 30 °C for 1 h in the presence or absence of GSK3β. Reaction products were immunoblotted as indicated. (e) GSK3-mediated phosphorylation of p100 is required for p100 binding to Fbxw7α in vitro. In vitro-translated, FLAG-tagged p100 was incubated with or without GSK3β before incubation with in vitro-translated Fbxw7α. FLAG-tagged immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted as indicated. 5% of inputs are shown. (f) GSK3 phosphorylates p100 in vivo. MEFs were treated with dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) or the GSK3 inhibitor GSK3i IX (5 μM). Cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated. (g) In vivo binding between p100 and Fbxw7α depends on GSK3 activity. Nfκb2−/− MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing FLAG-tagged p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala). Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of GSK3i IX for 12 h. FLAG-tagged immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted as indicated. (h) p100 is ubiquitylated in vitro in a degron- and SCFFbxw7α-dependent manner. [35S]-in vitro-translated (IVT) p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala) was incubated at 30 °C with a ubiquitylation mix. SCFFbxw7α was added to the reaction for the indicated times. Reactions were subjected to SDS–PAGE and analysed by autoradiography. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

Next, we systematically mapped the Fbxw7α-binding motif of human p100. A set of p100 mutants with serial deletions narrowed the binding motif to a C-terminal region between amino acids 702 and 720 (Supplementary Fig. S1d,e). This region contains a conserved sequence resembling the canonical Fbxw7 degradation motif (degron) S/TPPXS/E (Supplementary Fig. S1f). Further mutational analysis of p100 revealed Ser 707 and Ser 711 as residues contributing to its interaction with Fbxw7α (Supplementary Fig. S1g). A p100 mutant containing alanine substitutions at both Ser 707 and Ser 711 [p100(Ser707/711Ala)] failed to bind Fbxw7α (Fig. 1b).

To investigate whether serine phosphorylation plays a role in the interaction of p100 with Fbxw7α, we used immobilized, synthetic peptides spanning the candidate phosphodegron (amino acids 702–715 in human p100). Only a peptide doubly phosphorylated on Ser 707 and Ser 711 efficiently bound Fbxw7α (but not βTrCP; Fig. 1c), indicating that Fbxw7α binds doubly phosphorylated p100.

To further study the role of p100 phosphorylation, we generated a phospho-specific antibody against phospho-serine at position 707 (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b). Using this tool, we found that Fbxw7α, but not βTrCP, co-immunoprecipitated p100 phosphorylated on Ser 707, whereas βTrCP, but not Fbxw7α, co-immunoprecipitated p100 phosphorylated at Ser 866 and Ser 870 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S2c).

As previous studies have shown that Fbxw7 substrates are phosphorylated by GSK3 (ref. 5), we investigated whether this was the case for p100. GSK3 was able to phosphorylate p100 on Ser 707 in vitro and promoted its binding, but not the binding of p100(Ser707/711Ala), to Fbxw7α (Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Fig. S2d), confirming that only p100 phosphorylated on Ser 707 associates with Fbxw7α. We next asked whether p100 is a target of GSK3 in vivo. Treatment of mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) with a GSK3 inhibitor33 (GSK3i IX) markedly reduced the level of phosphorylation of Ser 707 on p100 to an extent similar to that observed for GSK3 phosphorylation sites in c-Myc and β-catenin (Fig. 1f). In contrast, phosphorylation of Ser 866/870 (the βTrCP degron) was unaffected by GSK3 inhibition. Furthermore, increasing doses of GSK3i IX decreased the affinity of Fbxw7α for p100 (Fig. 1g). Taken together, these results indicate that GSK3 phosphorylates p100 on the Fbxw7α degron, promoting binding to Fbxw7α.

Last, we reconstituted the ubiquitylation of p100 in vitro. Wild-type p100, but not p100(Ser707/711Ala), was efficiently ubiquitylated only when recombinant SCFFbxw7α was present in the reaction mix (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. S2e), supporting the hypothesis that Fbxw7α directly controls the ubiquitylation of p100.

Fbxw7α-mediated degradation of p100 occurs in the nucleus independently of NF-κB signalling

p100 is predominantly a cytoplasmic protein, but on a brief treatment of cells with the CRM1/exportin1 inhibitor Leptomycin B (LMB), p100 accumulated in the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. S2f,g), indicating that it actively shuttles between the cytoplasm and nucleus, as previously suggested34. Knockdown analysis of the Fbxw7 isoforms using established siRNAs targeting Fbxw7α, Fbxw7β and Fbxw7γ, either individually or all at once35,36, revealed that the α (nuclear) isoform regulates p100 cellular abundance (Supplementary Fig. S2h).

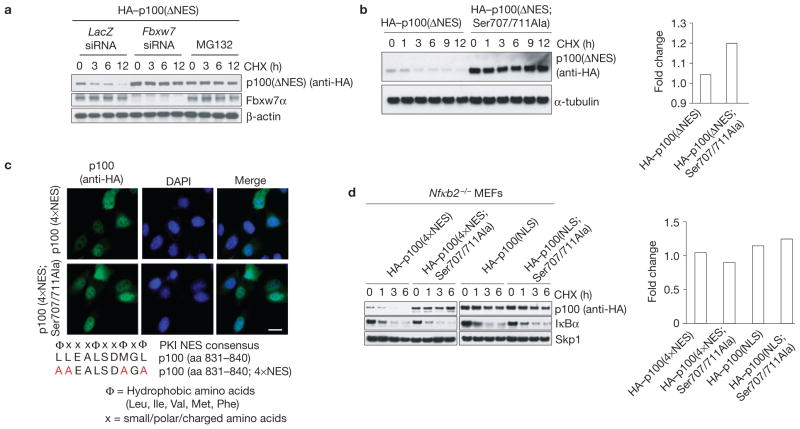

To expand our studies on the nuclear regulation of p100, we generated p100(ΔNES), a C-terminal deletion mutant of p100 that lacks the last 180 amino acids, but retains the Fbxw7α degron. p100(ΔNES) constitutively localizes to the nucleus34 (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Depletion of Fbxw7 or treatment of cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 increased the half-life of p100(ΔNES) (Fig. 2a). Moreover, mutation of Ser 707 and Ser 711 to alanine in the context of p100(ΔNES) significantly stabilized this largely nuclear protein (Fig. 2b). Next, on the basis of homology with NES consensus sequences, we identified the NES sequence in p100 (Fig. 2c). p100(4×NES), a p100 mutant in which alanine was substituted for four residues within the NES (Leu 831, Leu 832, Met 838 and Leu 840), mislocalized to the nucleus (Fig. 2c). p100(4×NES) exhibited a short half-life, and the Ser707/711Ala mutations stabilized the protein (Fig. 2d). In contrast, p100(NLS), a mutant in which the amino acids of the p100 nuclear localization signal (338KRRK341) were mutated to alanine (Supplementary Fig. S3b), was stable and unaffected by mutations in the Fbxw7α degron (Fig. 2d). We also found that retrovirally expressed wild-type p100 exhibited a short half-life in the nuclear fraction of Nfκb2−/− MEFs, and the Ser707/711Ala mutations stabilized nuclear p100 (Supplementary Fig. S3c). Furthermore, Fbxw7 silencing or treatment with MG132 stabilized nuclear p100 in cells pre-treated with LMB (Supplementary Fig. S3d).

Figure 2.

Fbxw7α controls p100 stability in the nucleus. (a) A constitutively nuclear mutant of p100 (p100(ΔNES)) is stabilized by proteasome inhibitor treatment or silencing of Fbxw7. HeLa cells were infected with a retrovirus expressing HA-tagged p100(ΔNES) and treated with either siRNAs or MG132. Cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times, and total cell lysates were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. (b) A constitutively nuclear mutant of p100 (p100(ΔNES)) is stabilized by mutation of Ser 707 and Ser 711 to alanine. HeLa cells were infected with retroviruses expressing either HA-tagged p100(ΔNES) or HA-tagged p100(ΔNES; Ser707/711Ala) and treated with cycloheximide for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated (left). mRNA levels of retrovirally expressed p100 were analysed by quantitative PCR (right). (c) Identification of an NES in p100. MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing either HA-tagged p100(4×NES) or HA-tagged p100(4×NES; Ser707/711Ala) and stained with an antibody against HA. Scale bar, 20 μm. The identified consensus NES is shown on the bottom. aa, amino acids. (d) A constitutively nuclear mutant of p100 (p100(4×NES)) is stabilized by mutation of Ser 707 and Ser 711 to alanine. Nfκb2−/− MEFs were infected with a retrovirus expressing HA-tagged p100(4×NES), HA-tagged p100(4×NES; Ser707/711Ala), HA-tagged p100(NLS) or HA-tagged-p100(NLS; Ser707/711Ala), treated with cycloheximide for the indicated times and total cell lysates were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated (left). IκBα is shown as a positive control for cycloheximide activity. mRNA levels of retrovirally expressed p100 were analysed by quantitative PCR (right). Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

To study how Fbxw7α influences levels of endogenous p100, we activated the non-canonical NF-κB pathway in MEFs using an antibody agonistic to the lymphotoxin-β receptor21 (anti-LTβR). In the nuclei of Fbxw7flox/flox MEFs, levels of p100 increased in parallel with p52 generation (Fig. 3a–c). In comparison, unstimulated Fbxw7−/− MEFs exhibited higher levels of nuclear p100 and this difference was particularly evident for the fraction of p100 phosphorylated on Ser 707 (Fig. 3b). On LTβR ligation, levels of cytoplasmic p100 decreased in Fbxw7flox/flox and Fbxw7−/− MEFs with similar kinetics (despite higher levels in knockout cells, possibly owing to its nucleus–cytoplasm shuttling). Pharmacologic inhibition of GSK3 produced results similar to loss of Fbxw7 (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

p100 is degraded by Fbxw7α and GSK3 independently of NF-κB signalling, but NF-κB proteins compete with Fbxw7α for binding to p100. (a) p100 accumulates in the nucleus on LTβR activation. MEFs were treated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies, fixed and stained with antibodies against the N- or C-terminus of p100 (green). A similar pattern was observed with an antibody against either the N-terminus (recognizing both p100 and p52) or the C-terminus (recognizing only p100). Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Levels of p100 are higher in Fbxw7 −/− MEFs than in Fbxw7flox/flox MEFs. MEFs were stimulated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies and collected at the indicated times. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. (c) Levels of p100 are increased on GSK3 inhibition. MEFs were incubated with GSK3i IX and stimulated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. (d) p52 induces the accumulation of nuclear p100. Nfκb2−/− MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing p100 and HA-tagged p52, fixed and stained with antibodies against the C-terminus of p100 (green) and the HA tag (red). DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. (e) p52 induces p100 accumulation in control cells, but not in cells depleted of Fbxw7. HeLa Tet-ON HA-tagged p52 cells were treated with siRNA against LacZ or FBXW7. Doxycycline (DOX) was added to cells at the indicated times. Total cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated. (f) p52 competes with Fbxw7α for binding to p100 in vivo. HEK293 cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding either FLAG-tagged p100 or FLAG-tagged p100(Ser707/711Ala). Increasing amounts of HA-tagged p52 plasmid were transfected. Proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell extracts with anti-FLAG resin (anti-FLAG), and the immunoprecipitates (IPs) were immunoblotted as indicated. The first lane shows cells transfected with an empty vector (EV). (g) The interaction of Fbxw7 with p100 is disrupted after treatment of cells with anti-LTβR. MEFs were treated with anti-LTβR for 18 h, collected, lysed and endogenous Fbxw7α was immunoprecipitated. Immunocomplexes were analysed by western blotting for the indicated proteins. Fbxw7−/− cells were used as a negative control. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

Together, these data support the hypothesis that Fbxw7α constitutively targets p100 for degradation in the nucleus.

NF-κB proteins compete with Fbxw7α for p100

The nuclear accumulation of p100 following LTβR ligation has been attributed to de novo synthesis37. We reasoned that stabilization of nuclear p100 also contributes to its elevated levels in the nucleus. As NF-κB proteins bind the ARD of p100, the Fbxw7α phosphodegron of p100 is located at the C-terminal end of the ARD (between the sixth and seventh ankyrin repeats) and NF-κB proteins (particularly p52 and RelB) accumulate in the nucleus on LTβR ligation, we investigated whether NF-κB proteins compete with Fbxw7α for p100 binding. Expression of exogenous p52 stabilized p100 (Fig. 3d,e), but this effect was no longer observed in cells depleted of Fbxw7 (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, p52 or RelB reduced the binding between p100 and Fbxw7α in a concentration-dependent manner both in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. S4a,b). Further evidence also supports a competition model. First, following LTβR ligation, the interaction of nuclear p100 with Fbxw7α decreased (Fig. 3g), whereas overall binding of RelA and RelB to p100 decreased in the cytoplasm and increased in the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. S4c). Second, deoxycholate analysis of p100–Fbxw7 complexes revealed that the fraction of p100 bound to Fbxw7α associates with RelB only through RHD:RHD interactions (Supplementary Fig. S4d). Together, these results indicate that NF-κB proteins induce the stabilization of p100 by competing with Fbxw7α for the ARD of p100.

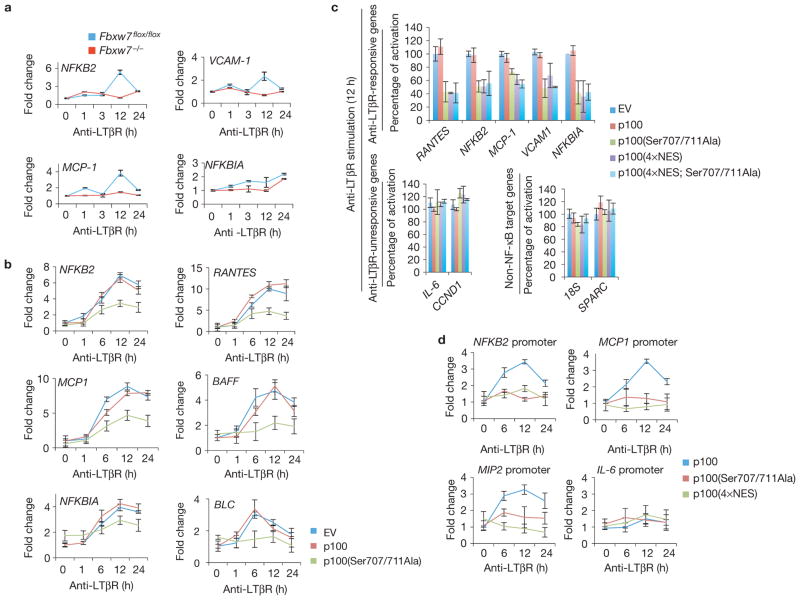

Clearance of nuclear p100 is required for efficient NF-κB activation

We next assessed the effect of Fbxw7 loss on the expression of NF-κB target genes with roles in lymphoid development and inflammation. LTβR stimulation in Fbxw7flox/flox MEFs induced the expression of several genes, including NFKB2, MCP-1, VCAM-1 and NFKBIA (Fig. 4a). This response was attenuated in MEFs lacking Fbxw7, which exhibited a significant reduction in the amplitude of target gene transcription. Consistently, expression of the stable p100(Ser707/711Ala) mutant, but not wild-type p100, inhibited the transcription of NF-κB target genes (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, treatment of cells with GSK3i IX also inhibited NF-κB activation following LTβR stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S5a). Similarly to our observations with anti-LTβR, Fbxw7 silencing or GSK3 inhibition attenuated the NF-κB response to either CD40L or TNF (Supplementary Fig. S5b–e). The latter finding is in agreement with a role for p100 as a general inhibitor of NF-κB signalling38.

Figure 4.

Clearance of p100 from the nucleus is crucial for non-canonical NF-κB signalling. (a) LTβR-dependent gene transcription is impaired in cells lacking Fbxw7. Fbxw7flox/flox and Fbxw7 −/− MEFs were treated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies and collected at the indicated times. Levels of the indicated mRNAs were determined by quantitative real-time PCR (±s.d., n = 3). The value for the amount of PCR product present in Fbxw7flox/flox MEFs was set as 1. (b) LTβR-dependent gene transcription is impaired in cells expressing stable p100(Ser707/711Ala). MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing empty vector (EV), p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala), stimulated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies and processed as in a. Levels of the indicated mRNAs were determined by quantitative PCR (±s.d., n = 3). The value for the amount of PCR product present in empty-vector-infected MEFs was set to 1. (c) LTβR-dependent gene transcription is impaired in cells expressing constitutively nuclear p100(4×NES). MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing empty vector, p100, p100(Ser707/711Ala), p100(4×NES) or p100(4×NES; Ser707/711Ala) and stimulated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies. After 12 h of stimulation, levels of the indicated mRNAs were determined by quantitative PCR (±s.d., n = 3) and normalized to the transcriptional activation measured in cells infected with empty vector. (d) LTβR-dependent binding of RelB to NF-κB elements is impaired in cells expressing p100(Ser707/711Ala) or p100(4×NES). MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing p100, p100(Ser707/711Ala) or p100(4×NES) and stimulated with agonistic anti-LTβR antibodies. DNA precipitated with an anti-RelB antibody was amplified by real-time PCR using primers flanking the indicated gene promoters (±s.d., n = 3). The LTβR-unresponsive promoter of IL-6 was used as a negative control. The value for the amount of PCR product present in MEFs infected with wild-type p100 was set as 1.

To further investigate the relevance of p100 accumulation in the nucleus, we investigated whether a constitutively nuclear p100 mutant is capable of inhibiting LTβR signalling. To this end, we expressed p100(4×NES) in MEFs and stimulated the cells with anti-LTβR. After 12 h of stimulation, the transcription of several LTβR-responsive genes (RANTES, NFKB2, MCP-1, VCAM-1 and NFKBIA), but not LTβR-unresponsive genes (IL-6, CCND1) or non-NF-κB target genes (18S, SPARC), was impaired by expression of the nuclear p100 mutant (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. S6a). The expression of stable p100(Ser707/711Ala) or a combined nuclear and stable p100 mutant (4×NES; Ser707/711Ala) impaired LTβR-dependent gene transcription to a similar extent (Fig. 4c), as did the expression of a constitutively cytoplasmic p100(NLS) mutant (Supplementary Fig. S6a). These results show that forced localization of p100 to either the nucleus or cytoplasm inhibits NF-κB signalling.

To analyse whether the transcriptional effect is a consequence of reduced binding of NF-κB proteins at the promoters of endogenous target genes, we carried out chromatin immunoprecipitation assays using an anti-RelB antibody. We found that, compared with wild-type p100, expression of p100(Ser707/711Ala) or p100(4×NES) decreased the LTβR-induced binding of RelB to NF-κB elements at the NFKB2, MCP1 and MIP2 promoters (Fig. 4d). RelB association with the promoter of the LTβR-unresponsive gene IL-6 was unaffected by p100 mutants. The expression of a combined nuclear and stable mutant (4×NES; Ser707/711Ala) impaired RelB enrichment to a similar extent as p100(Ser707/711Ala) (Supplementary Fig. S6b).

Thus, inefficient clearance of nuclear p100 (due to lack of Fbxw7, mutation of the p100 degron, GSK3 inhibition or mutation of the p100 NES) inhibits NF-κB target gene transcription on NF-κB pathway stimulation.

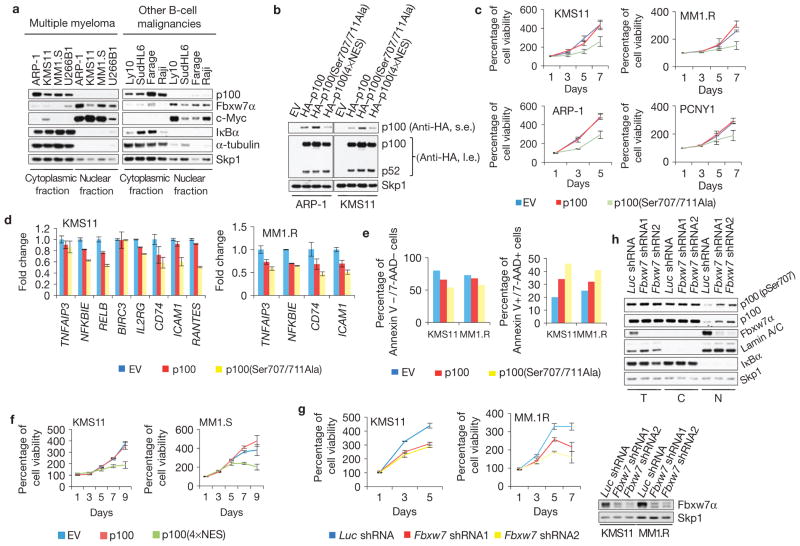

Fbxw7α-mediated degradation of p100 is necessary for the proliferation and survival of multiple myeloma cells

Multiple myeloma cells often exhibit and require elevated NF-κB activity27. We observed that, in HMMCLs, most p100 is localized in the cytoplasm, in contrast with Fbxw7α, which is exclusively nuclear (Fig. 5a). To assess the relevance of the Fbxw7α–GSK3–p100 regulatory axis in this cancer, we expressed our p100 mutants in four HMMCLs (KMS11, MM1.R, ARP-1 and PCNY1) that are characterized by elevated NF-κB activity due to mutations in the non-canonical pathway (that is, TRAF3-inactivating mutations)28,29. Compared with wild-type p100 or an empty vector, expression of p100(Ser707/711Ala) resulted in decreased proliferation of all four HMMCLs investigated (Fig. 5b,c). Moreover, NF-κB target gene transcription was reduced in cells expressing the stable p100 mutant (Fig. 5d). Accordingly, expression of p100(Ser707/711Ala) decreased cell viability and induced apoptosis (Fig. 5e). Similarly, either expression of p100(4×NES) or Fbxw7 knockdown (the latter inducing accumulation of p100 in the nucleus) decreased the proliferation rate of HMMCLs (Fig. 5b,f–h). These effects were not due to impairment of p100 processing because p52 generation was comparable in cells expressing wild-type p100 and the p100(Ser707/711Ala) mutant, depleted of Fbxw7 or treated with GSK3 inhibitors (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 5.

p100 degradation promotes multiple myeloma cell survival. (a) In B-cell lines, p100 is cytoplasmic, whereas Fbxw7α is largely nuclear. Subcellular fractionation was carried out on HMMCLs (ARP-1, KMS11, MM1.S and U266B1), DLBCL (Ly10, SudHL6 and Farage) and Burkitt’s lymphoma (Raji) cell lines. Lysates were immunoblotted as indicated. IκBα and α-tubulin, cytoplasmic controls. c-Myc, nuclear control. (b) Stable p100(Ser707/711Ala) and p100(4×NES) are correctly processed in HMMCLs. HMMCLs were infected with retroviruses encoding HA-tagged p100, p100(Ser707/711Ala), p100(4×NES) or empty vector (EV). Cell extracts were immunoblotted as indicated. Short exposure (s.e.) and long exposure (l.e.) are shown. (c) Expression of stable p100 mutant impairs HMMCL growth. HMMCLs were infected with retroviruses expressing p100, p100(Ser707/711Ala) or empty vector. Cell proliferation was monitored by MTS assay and normalized on empty vector at day 1, arbitrarily set as 100%. Error bars represent s.d., n = 4. (d) Stable p100 expression impairs NFκB-dependent transcription in HMMCLs. HMMCLs were infected as in c. Steady-state levels of the indicated mRNAs were analysed by quantitative PCR (±s.d., n = 3). PCR product amount in empty vector was set as 1. (e) Expression of stable p100 promotes apoptosis of HMMCLs. HMMCLs were infected as in c. At 72 h post-infection, cells were stained with Annexin V/7-AAD and analysed by flow cytometry. Apoptosis and cell viability were calculated as the percentage of Annexin V/7-AAD double-positive and double-negative cells, respectively. (f) Forced nuclear localization of p100 inhibits HMMCLs proliferation. HMMCLs were infected with retroviruses encoding p100, p100(4×NES) mutant or empty vector. Cell viability was monitored as in c. Values were normalized on the empty vector at time 0. Error bars represent s.d., n = 4. (g) Fbxw7 depletion impairs HMMCL growth. HMMCLs were infected with the indicated shRNA-encoding lentiviruses. Cell viability was monitored as in c (left panels). Values were normalized on Luc shRNA at time 0. Error bars represent s.d., n = 4. Fbxw7 protein levels were analysed by immunoblotting (right panel). (h) Fbxw7 depletion stabilizes nuclear p100. HMMCLs were infected as in g. Total (T), cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were immunoblotted as indicated. IκBα and Lamin A/C are cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

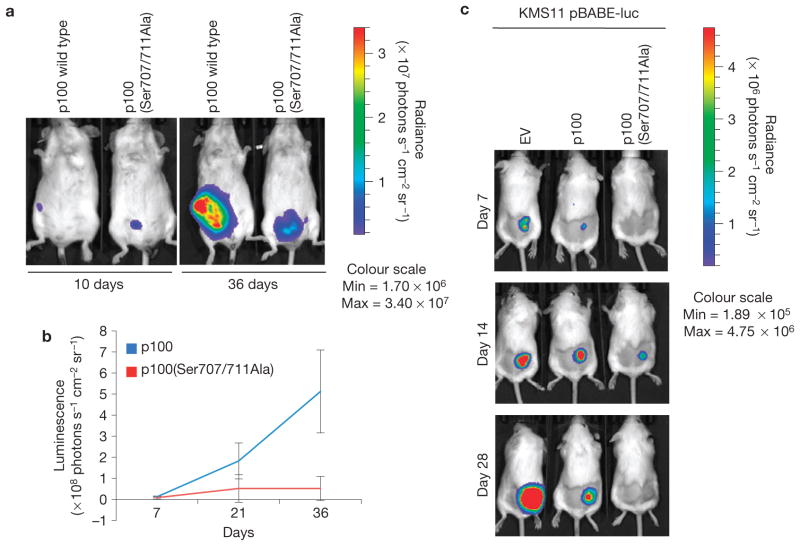

Finally, we transduced KMS11 cells with retroviruses encoding p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala) and a luciferase reporter cassette. Equal ratios of relative light units per cell number were injected intraperitoneally or subcutaneously into SCID Beige mice (Fig. 6a–c). The expression of p100(Ser707/711Ala) in KMS11 cells inhibited tumour growth, as revealed by in vivo imaging.

Figure 6.

Expression of a stable p100 mutant impairs the growth of HMMCLs xenotransplanted into immunodeficient mice. (a) KMS11 cells were infected with retroviruses expressing either p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala) and a firefly luciferase reporter, before intraperitoneal injection of SCID Beige mice. Cell growth was monitored by in vivo imaging. (b) Bioluminescence quantification of a with Living Image software (Xenogen). Error bars represent s.d., n = 3. (c) KMS11 cells were infected with retroviruses expressing a firefly luciferase reporter and an empty vector (EV), p100 or p100(Ser707/711Ala). Three days after infection, cells were injected subcutaneously into SCID Beige mice. Cell growth was monitored by in vivo imaging at 7, 14 and 28 days following injection. Bioluminescence was quantified with Living Image software (Xenogen).

Thus, constitutive p100 degradation by Fbxw7α/GSK3 sustains the survival of multiple myeloma cells with aberrant NF-κB activity.

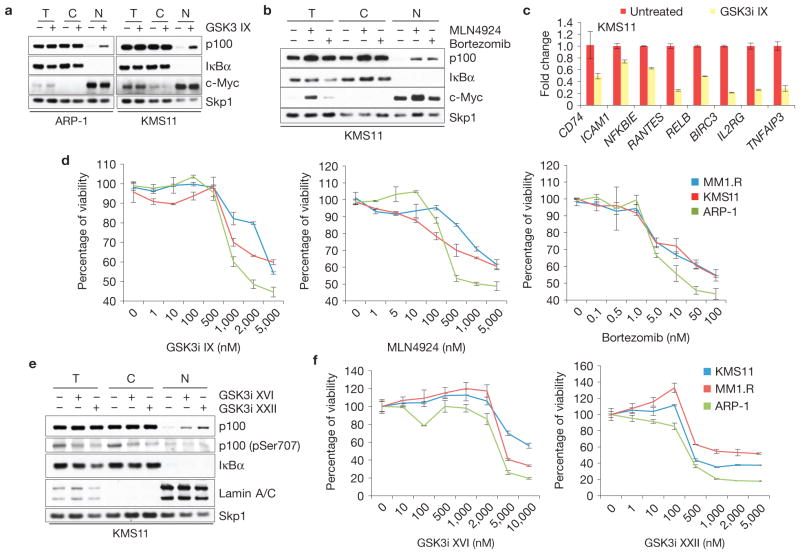

p100 stabilization contributes to the cytotoxic effect of GSK3 inhibition in multiple myeloma cells

Bortezomib, an inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, is used for the treatment of multiple myeloma39. Recently, the neddylation inhibitor MLN4924, which blocks the function of all Cullin–RING ligases (including SCFFbxw7α), entered phase I clinical trials for multiple myeloma40. As stabilization of nuclear p100 induces cell death in HMMCLs, we investigated whether chemical inhibition of GSK3 could be used as a therapeutic strategy in multiple myeloma. First, we treated ARP-1 and KMS11 cells with GSK3i IX. Cell fractionation revealed significant stabilization of p100 in the nucleus of these cells, similar to what was observed after bortezomib or MLN4924 treatment (Fig. 7a,b). Accordingly, NF-κB target gene transcription was inhibited after treatment of KMS11 cells with GSK3i IX (Fig. 7c), indicating an important role for GSK3 in sustaining aberrant NF-κB activity in HMMCLs. Next, we investigated whether inhibition of GSK3 affected the viability of HMMCLs. Similarly to treatment with bortezomib or MLN4924, GSK3 inhibition results in the death of HMMCLs (Fig. 7d). Comparable results were obtained using next-generation GSK3 inhibitors, such as GSK3i XVI and GSK3i XXII (Fig. 7e,f).

Figure 7.

Pharmacologic inhibition of GSK3, Cullin–RING ligases or the proteasome impairs the growth of multiple myeloma cells. (a) GSK3 inhibition induces nuclear accumulation of p100 in HMMCLs. KMS11 and ARP-1 cells were treated with GSK3i IX (2 μM for 8 h). Total (T), cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were isolated and analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. Cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, IκBα and c-Myc, respectively, are also shown. (b) Proteasome or Cullin–RING ligase inhibitors induce nuclear accumulation of p100 in HMMCLs. KMS11 cells were treated with either bortezomib or MLN4924 for 4 h. Total, cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. Cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, IκBα and c-Myc, respectively, are also shown. (c) NF-κB-dependent transcription is impaired in HMMCLs treated with a GSK3 inhibitor. KMS11 cells were treated with GSK3i IX and the steady-state levels of the indicated mRNAs were analysed by real-time PCR (±s.d., n = 3). The value for the amount of PCR product present in DMSO-treated cells was set as 1. (d) Inhibition of GSK3, Cullin–RING ligases or the proteasome decreases the viability of HMMCLs. KMS11, MM1.R and ARP-1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of GSK3i IX, MLN4924 or bortezomib. Cell viability was measured by MTS assay at 72 h after treatment and individually normalized to untreated cells (0 nM), arbitrarily set as 100%. Error bars represent s.d., n = 4. (e) Next-generation GSK3 inhibitors induce accumulation of nuclear p100 in HMMCLs. KMS11 cells were treated with GSK3i XVI or GSK3i XXII (5 μM and 1 μM for 8 h, respectively). Total, cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were isolated and analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. Cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, IκBα and Lamin A/C, respectively, are also shown. (f) Next-generation GSK3 inhibitors decrease the viability of HMMCLs. KMS11, MM1.R and ARP-1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of GSK3i XVI or GSK3i XXII. Cell viability was measured by MTS assay at 72 h after treatment. Each value was individually normalized on the DMSO-treated cells, arbitrarily set as 100%. Error bars represent s.d., n = 4. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

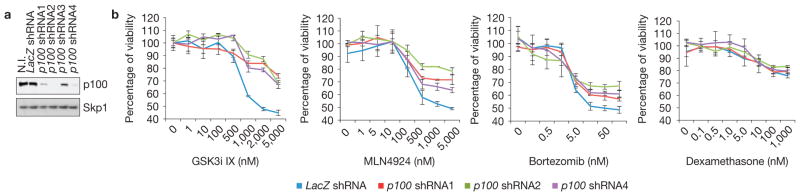

To assess whether the cytotoxic effect of GSK3i IX was attributable to p100 stabilization, we depleted p100 in ARP-1 cells using lentiviruses encoding three different short hairpin RNAs (Fig. 8a). Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of GSK3i IX, bortezomib, MLN4924 or dexamethasone and assayed for viability (Fig. 8b). p100 knockdown desensitized ARP-1 cells to GSK3i IX, indicating that the presence of p100 contributes to the cytotoxic effect of GSK3i IX. Instead, a milder desensitization to MLN4924 and, to an even lesser extent, bortezomib was detectable on p100 knockdown. Finally, p100 depletion had no effect on cells treated with dexamethasone, another clinically relevant compound used for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

Figure 8.

p100 contributes to the sensitivity of multiple myeloma cells to GSK3 inhibition. (a) Efficient knockdown of p100 in HMMCLs. ARP-1 cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding shRNAs targeting p100 or a control shRNA against LacZ. Cell extracts were then subjected to immunoblotting as indicated. (b) p100 knockdown desensitized ARP-1 cells to GSK3i IX. ARP-1 cells were infected with the indicated lentiviruses and treated with increasing concentrations of GSK3i IX, MLN4924, bortezomib or dexamethasone. Cell viability was measured by MTS assay at 72 h after treatment and normalized to the untreated LacZ shRNA (0 nM), arbitrarily set as 100%. Error bars represent s.d., n = 4. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that Fbxw7α promotes degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor protein p100. Phosphorylation of p100 on Ser 707 and Ser 711 by GSK3 is a prerequisite for the p100–Fbxw7α interaction. Although predominantly cytoplasmic, p100 shuttles continuously between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. We show that p100 degradation by Fbxw7α and GSK3 occurs in the nucleus, independently from NF-κB activation. However, although independent from NF-κB signalling, p100 clearance from the nucleus (through Fbxw7α-mediated degradation or nuclear exclusion by a newly identified nuclear export signal in the C-terminus of p100) is a prerequisite for binding of RelB at the promoters of target genes and efficient activation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. In fact, deletion of the Fbxw7 gene, inhibition of GSK3, expression of a stable p100 mutant or expression of a constitutively nuclear p100 mutant attenuates the NF-κB response. The function of Fbxw7α in the NF-κB response is consistent with mouse genetic data showing that conditional knockout of Fbxw7 in haematopoietic stem cells induces a significant decrease in the number of both immature and mature B cells41, which rely on BAFF-mediated NF-κB signalling for homeostasis42. Moreover, in agreement with our findings, fibroblasts from GSK3-deficient embryos exhibit reduced activation of NF-κB signalling43.

Whereas phosphorylation of p100 on Ser 707 is constitutive, phosphorylation of p100 on Ser 866/870 is induced by NF-κB stimuli, leading to p100 cleavage into p52 (refs 23,24). Accordingly, p52 can be generated from p100(Ser707/711Ala), but not from a p100(Ser866/870) mutant. Interestingly, cytoplasmic p100 is phosphorylated on both Ser 707 and Ser 866/870, whereas nuclear p100 is phosphorylated only on Ser 707. Furthermore, p100 phosphorylated on Ser 707 binds only nuclear Fbxw7α, whereas p100 phosphorylated on Ser 866/870 binds only βTrCP. Thus, differentially localized and modified fractions of p100 undergo distinct regulation by the ubiquitin proteasome system.

From yeast to mammals, inducible phosphorylation is the dominant mechanism controlling the recruitment of substrates to F-box proteins2,5. As phosphorylation of the p100 degron is constitutive, we investigated how Fbxw7α-mediated proteolysis of p100 is regulated. We found that NF-κB proteins are able to induce p100 stabilization through Fbxw7α displacement. These observations indicate that the nuclear accumulation of NF-κB proteins (p52 and RelB) induced by NF-κB signalling may lead to p100 stabilization through competition with Fbxw7α. Thus, we propose a control mechanism, in which recognition of a substrate by an F-box protein is negatively regulated by accumulation of the substrate’s interacting partners, physically disrupting the ligase–substrate interaction.

The mechanism of p100 degradation has implications for B-cell malignancies. Constitutive activation of the NF-κB pathway has been found in many lymphoid diseases and contributes to the malignant transformation of B-cell lineages, including plasma cells27–30. Pharmacologic inhibition of the proteasome28 or Cullin–RING ligases44 induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma and B-cell lymphoma cell lines, partially by inhibiting NF-κB. Here, we have shown that inhibition of GSK3-mediated signalling (for example, by expressing a phospho-defective mutant of p100 or through pharmacologic inhibition of GSK3) impairs the survival of HMMCLs both in cell systems and xenotransplant models. Interestingly, the toxicity of GSK3 inhibition can be substantially reduced by knockdown of p100. Thus, the intersection of Fbxw7–GSK3–p100 may serve as a potential intervention point for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Moreover, it is likely that the effects observed in multiple myeloma may be generalized to other B-cell neoplasms, especially those addicted to NF-κB.

Together, our studies have revealed an unexpected pro-survival role for Fbxw7. A number of cancers, including T-ALL, breast cancers, cholangiocarcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma and head and neck squamous carcinoma7,8,11,45, often carry hemizygous or homozygous mutations in the FBXW7 gene. Most cancer-associated FBXW7 point mutations result in the accumulation of substrates (for example, Notch, c-Myc, cyclin E and Mcl1) due to reduced binding. Interestingly, mutations of Fbxw7 have not been detected in 38 multiple myeloma samples13, 24 HMMCLs (L.B., W. M. Kuehl and M.P., unpublished results), 70 primary B-ALLs (I. Aifantis, personal communication, and ref. 12), 20 B-CLLs (ref. 12) and 13 DLBCLs (ref. 46). Our findings indicate that, in contrast to T cells, B cells are uniquely dependent on Fbxw7 function for survival. Although characterized as a tumour suppressor, Fbxw7 therefore functions as a pro-survival gene in multiple myeloma through its control of NF-κB activity.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/naturecellbiology

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank I. Aifantis, H. J. Cho, G. Franzoso, W. M. Kuehl and A. Ventura for reagents; B. Aranda-Orgilles for her contribution; and I. Aifantis, G. Franzoso, K. Nakayama, S. Reed and J. R. Skaar for critically reading the manuscript. M.P. is grateful to T. M. Thor for continuous support. This work was supported in part by grant 5P30CA016087-33 from the National Cancer Institute, a fellowship from the American Italian Cancer Foundation and NIH 5T32HL007151-33 to L.B., NIH T32 CA009161 grant to S.M. and grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM057587, R37-CA076584 and R21-CA161108) and the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation to M.P. M.P. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.B. conceived and directed the project. L.B. and S.E.M. designed and carried out most experiments. L.S. and O.O. helped with the mouse experiments. C.K. carried out the in vitro experiments shown in Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Figs S2d and S5b. V.B. and K.S.E-J. carried out the mass spectrometry analysis of the Fbxw7α complex purified by L.B. A.H. provided constructs, cell lines and advice. M.P. coordinated the work and oversaw the results. L.B., S.M. and M.P. wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints

References

- 1.Skaar JR, D’Angiolella V, Pagan JK, Pagano MS. F box proteins II. Cell. 2009;137:e1351–e1358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin–RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoeck JD, et al. Fbw7 controls neural stem cell differentiation and progenitor apoptosis via Notch and c-Jun. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1365–1372. doi: 10.1038/nn.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welcker M, Clurman BE. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onoyama I, et al. Conditional inactivation of Fbxw7 impairs cell-cycle exit during T cell differentiation and results in lymphomatogenesis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2875–2888. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson BJ, et al. The SCFFBW7 ubiquitin ligase complex as a tumor suppressor in T cell leukemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1825–1835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajagopalan H, et al. Inactivation of hCDC4 can cause chromosomal instability. Nature. 2004;428:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature02313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millman SE, Pagano M. MCL1 meets its end during mitotic arrest. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:384–385. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mavrakis KJ, et al. A cooperative microRNA-tumor suppressor gene network in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) Nat Genet. 2011;43:673–678. doi: 10.1038/ng.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neil J, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to γ-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhoondi S, et al. FBXW7/hCDC4 is a general tumor suppressor in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9006–9012. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman MA, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–472. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109 (Suppl):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senftleben U, et al. Activation by IKKα of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-κB signaling pathway. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dejardin E, et al. The lymphotoxin-β receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-κB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coope HJ, et al. CD40 regulates the processing of NF-κB2 p100 to p52. EMBO J. 2002;21:5375–5385. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weih F, Caamano J. Regulation of secondary lymphoid organ development by the nuclear factor-κB signal transduction pathway. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:91–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramakrishnan P, Wang W, Wallach D. Receptor-specific signaling for both the alternative and the canonical NF-κB activation pathways by NF-κB-inducing kinase. Immunity. 2004;21:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarnegar B, et al. Unique CD40-mediated biological program in B cell activation requires both type 1 and type 2 NF-κB activation pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8108–8113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402629101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basak S, et al. A fourth IκB protein within the NF-κB signaling module. Cell. 2007;128:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mordmuller B, Krappmann D, Esen M, Wegener E, Scheidereit C. Lymphotoxin and lipopolysaccharide induce NF-κB-p52 generation by a co-translational mechanism. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:82–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Sun SC. NF-κB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-κB2 p100. Mol Cell. 2001;7:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong A, Sun SC. Genetic evidence for the essential role of β-transducin repeat-containing protein in the inducible processing of NF-κB2/p100. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22111–22114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonizzi G, et al. Activation of IKKα target genes depends on recognition of specific κB binding sites by RelB:p52 dimers. EMBO J. 2004;23:4202–4210. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller JR, Siebenlist U. Lymphotoxin β receptor induces sequential activation of distinct NF-κB factors via separate signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12006–12012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staudt LM. Oncogenic activation of NF-κB. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000109. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annunziata CM, et al. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-κB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keats JJ, et al. Promiscuous mutations activate the noncanonical NF-κB pathway in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razani B, et al. Negative feedback in noncanonical NF-κB signaling modulates NIK stability through IKKα-mediated phosphorylation. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra41. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao B, Oehlmann S, Sowa ME, Harper JW, Pavletich NP. Structure of a Fbw7-Skp1-cyclin E complex: multisite-phosphorylated substrate recognition by SCF ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell. 2007;26:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orian A, et al. SCF(β)(-TrCP) ubiquitin ligase-mediated processing of NF-κB p105 requires phosphorylation of its C-terminus by IκB kinase. EMBO J. 2000;19:2580–2591. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solan NJ, Miyoshi H, Carmona EM, Bren GD, Paya CV. RelB cellular regulation and transcriptional activity are regulated by p100. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1405–1418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Drogen F, et al. Ubiquitylation of cyclin E requires the sequential function of SCF complexes containing distinct hCdc4 isoforms. Mol Cell. 2006;23:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sangfelt O, Cepeda D, Malyukova A, van Drogen F, Reed SI. Both SCF(Cdc4 α) and SCF(Cdc4 α) are required for cyclin E turnover in cell lines that do not overexpress cyclin E. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1075–1082. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.8.5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derudder E, et al. RelB/p50 dimers are differentially regulated by tumor necrosis factor-α and lymphotoxin-β receptor activation: critical roles for p100. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23278–23284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shih VF, et al. Kinetic control of negative feedback regulators of NF-κB/RelA determines their pathogen- and cytokine-receptor signaling specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9619–9624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson PG, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. New Engl J Med. 2005;352:2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah JJ, et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of MLN4924, a novel NAE inhibitor, in patients with multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2009;114:735–736. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson BJ, et al. Control of hematopoietic stem cell quiescence by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbw7. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1395–1408. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie P, Stunz LL, Larison KD, Yang B, Bishop GA. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3 is a critical regulator of B cell homeostasis in secondary lymphoid organs. Immunity. 2007;27:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoeflich KP, et al. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3β in cell survival and NF-κB activation. Nature. 2000;406:86–90. doi: 10.1038/35017574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milhollen MA, et al. MLN4924, a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, is active in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma models: rationale for treatment of NF-κB-dependent lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:1515–1523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stransky N, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morin RD, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.