Abstract

Background:

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death in multicellular organisms, found in a wide variety of conditions, including inflammatory process, everywhere in the body, including the cornea and conjunctiva.

Aim:

To evaluate the effect of a new topical formulation of sphingosine-1 phosphate on preventing apoptosis of the corneal epithelium.

Setting:

Medical University.

Materials and Methods:

We tested several formulations suitable for topical application. Twenty-five rabbits were distributed among five groups. Group 1 comprised the controls. In Group 2, 20% ethanol was applied topically for 20 seconds; in Group 3, 50 μM topical sphingosine-1 phosphate was applied 2 hours prior to 20% ethanol application. In Group 4, 200 μM topical sphingosine-1 phosphate was applied 2 hours before the 20% ethanol application. In Group 5, only 200 μM topical sphingosine-1 phosphate was applied. Apoptosis was evaluated using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) assay. Pairwise comparisons were performed using t-tests with Scheffe's correction. Data were analyzed using STATA 9.0 statistical software.

Results:

A suspension of sphingosine-1 phosphate in the presence of Montanox 80 was stable and could be formulated without sonication. Epithelial apoptosis was detected only in Groups 2 and 3. Conclusion: Sphingosine-1 phosphate can prevent ethanol-induced apoptosis in the corneal epithelium of rabbits.

Keywords: Apoptosis, corneal epithelium, formulation, sphingosine-1 phosphate

Apoptosis involves a highly controlled, complex system of effector cascades that lead to the programmed death of single cells. It may occur after refractive surgery, with epithelial healing during dry eye syndrome, or as a response to infections or to toxic iatrogenic drops, or after topical application of alcohol. It plays a key role in cellular homeostasis and is implicated in various processes such as embryogenesis, development of malignancies, and aging or neurodegenerative diseases. Apoptosis is characterized by cytoplasmic and chromatin condensation, followed by DNA fragmentation, and is mediated by activation of specific cysteine proteases named caspases.[1] Dying cells that undergo the final stage of apoptosis are broken apart in several vesicles called apoptotic bodies. These are engulfed by phagocytes. This removal of dying cells occurs in an orderly manner, without eliciting an inflammatory response. Sphingolipids in the plasma membrane appear to modulate apoptosis.[2] Some sphingolipids, such as ceramide and sphingosine, behave as proapoptotic mediators, while others, such as sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), are inhibitory.[2]

Studies utilizing S1P in vivo describe its solubilization in a formulation of 5% polyethylene glycol, 2.5% ethanol, and 0.8% Tween-80.[3–5] However, this formulation presents difficulties that we attempted to circumvent by evaluating new, less complex formulations with the potential for topical application. In this study, we also attempted to determine whether S1P in novel formulations could provide protection from apoptosis induced by the application of 20% ethanol to the corneal epithelium.

Materials and Methods

White New Zealand rabbits, aged 7–9 weeks, weighing 1.5 kg each, and supplied by a certified breeder, were distributed into five groups of five animals each. The rabbits underwent surgery with general anesthesia using intramuscular injections of ketamine hydrochloride (250 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.5 mg/kg). Only the right eyes of each animal were treated. Group 1 comprised the negative controls where only topical tretracaine (Novartis, Pharma, SAS, Huningue, France) was applied. In Groups 2, 3, and 4, 20% ethanol was applied for 20 seconds to obtain a corneal epithelial apoptosis[6] [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

One milliliter of 20% alcohol solution is instilled into a small holding well on the corneal surface for 20 seconds to induce epithelial apoptosis

In Groups 3 and 4, S1P was applied 2 hours before ethanol application, at a concentration of 50 μM in Group 3 and at 200 μM in Group 4. In Group 5, only S1P was applied. Animals were sacrificed 4 hours after administration of the above-described premedication, using an intravenous injection of pentothal (0.05 g/kg). The eyes were enucleated and immediately fixed.

All experiments were humanely performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and with the animal ethics committee approval. S1P occurs as a white powder and was preserved at –20°C. Recommendations in the literature (http://www.avantilipids.com/SyntheticSphingosine-1-phosphate.asp) describe the following directions that were followed: add S1P to methanol:water 95:5 (0.5 mg/ml); heat the mixture (45°C–65°C methanol boiling point) and sonicate until a suspension is achieved; transfer the desired amounts of methanol:water stock solution to a glass vessel; remove the methanol:water solution using a stream of dry nitrogen; place the glass vessel into a warm (approximately 50°C) water bath; rotate the glass vessel during evaporation to form a thin film of S1P on the tube wall; and store the S1P at –20°C in a closed container. The S1P may then be preserved at –20°C for a maximum duration of 1 year. For subsequent use, it is advisable to re-suspend the S1P in bovine serum albumin (4 mg/ml) at 37°C in order to achieve a 125 μM S1P concentration.

After enucleation, 25 eyeballs were immediately fixed for 24 hours in 10% buffered formaldehyde. After fixation and gross examination, each cornea was removed behind the cornea and embedded in paraffin. Four-micron sections were cut from the paraffin blocks and stained with standard hematoxylin–eosin–saffron.

Sections were then examined for the presence of apoptosis using the commercially available DeadEnd Colorimetric terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) System (Promega), France. Determinations were performed in triplicate. Sections were cut at 4-micron intervals, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Following proteinase K permeabilization, the tissue was treated with an equilibration buffer. Slides were treated with the reagent mixture for 60 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was stopped in SSC buffer. After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity with hydrogen peroxide, the reaction was developed using streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and diaminobenzidine and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. A slide treated with DNase was used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

For microscopic analyses, retinal areas were randomly examined according to the pathological area. The cell count was carried out in a double-blind manner and the mean of the results obtained by the two observers is presented. Pairwise comparisons of the means of the number of nuclei at different times after surgery or after treatment were performed using t-tests with Scheffe's correction. The overall effect of time after surgery on the number of nuclei was assessed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data were analyzed using STATA 9.0 statistical software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

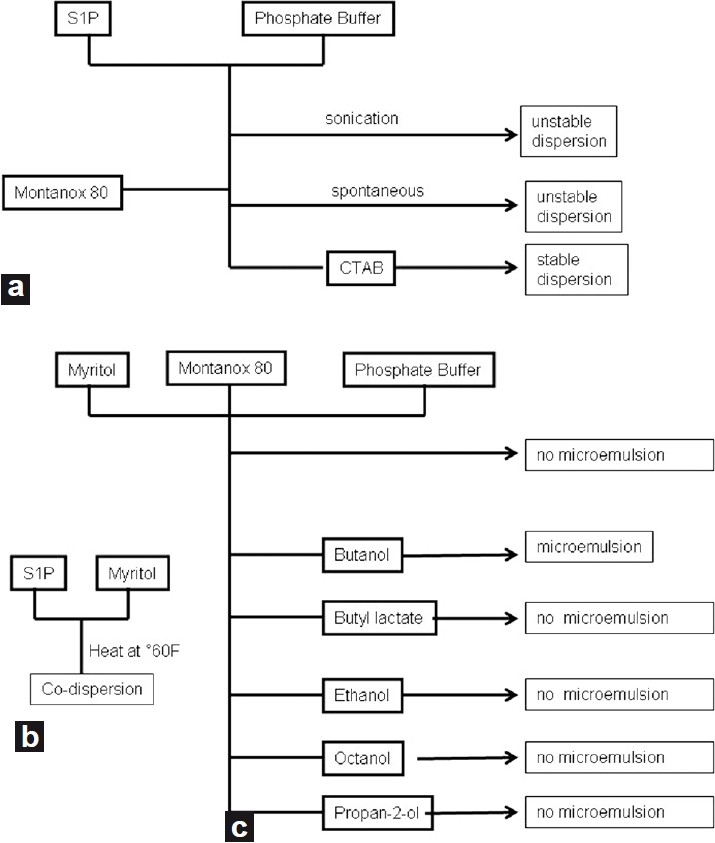

Being a lipid, S1P does not disperse spontaneously. The chemical structure of S1P, which is nearly amphiphilic, may allow its solubilization or its co-dispersion in water using a surfactant such as polysorbate 80 (Tween-80 or Montanox 80). Surfactants are compounds that modify the tension between two surfaces. The polysorbate 80 surfactant is biocompatible and has been utilized in many pharmaceutical formulations. It is associated with low toxicity (lethal amount 50 oral > 16 ml/kg). We evaluated an average weight proportion of 10% Montanox 80 (5 mg of phosphate buffer, 1 mg of S1P, 0.5 mg of Montanox).

The aqueous dispersion of the S1P in a phosphate buffer was possible. However, this preparation, without surfactant, was unstable as a precipitate formed after 24 hours. Consequently, to improve the stability of dispersion, we chose to add a surfactant. With the use of Montanox 80, there was dispersion similar to the sample prepared without surfactant, but even without sonication, the suspension was much more stable. Indeed, this preparation remained stable at room temperature for at least 1 month [Fig. 2].

Figure 2.

Diagram summarizing the test formulation of S1P (a) in aqueous medium, (b) in oily medium, (c) preparation of the eye drop micro-emulsion

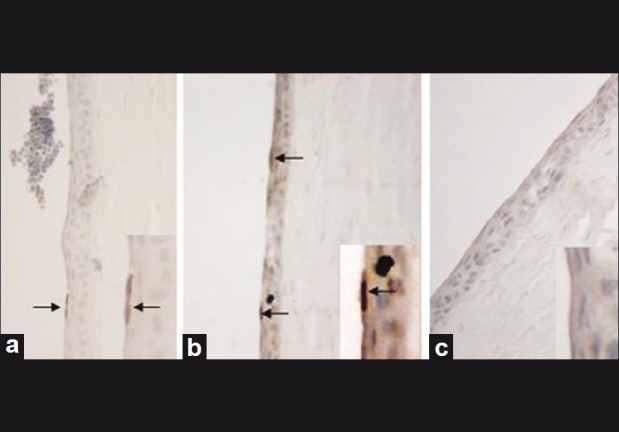

Using light microscopy, the epithelial cells in Groups 1, 4, and 5 did not show any morphologic changes. Conversely, in Groups 2 and 3, hydropic degeneration was found in all layers of epithelial cells. With the TUNEL assay, apoptosis was detected in all layers of the corneal epithelium in Groups 2 and 3. The mean apoptotic index was 10% (±3) in Group 2 (ethanol application alone) and 9.5% (±4) in Group 3 (cornea treated with ethanol and 50 μM S1P application) [Fig. 3]. However, no apoptosis was observed in Group 1 (negative control) or Group 4 (cornea treated with ethanol and 200 μM S1P application), or in Group 5 (only S1P application) [Fig. 3]. The apoptotic index in Groups 2 and 3 was found to be statistically higher than in all other groups (P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

(a): Apoptotic cells were observed in all layers of corneal epithelium after 20% ethanol exposure in Group 2 and (b) in Group 3. (c) No apoptosis was observed with 200 μM S1P application before ethanol aggression. Eye sections were prepared and labeled by TUNEL (×400 magnification)

Discussion

Apoptosis may occur after refractive surgery, with epithelial healing during dry eye syndrome, or as a response to infections or to toxic iatrogenic drops. After photoablation, keratocyte apoptosis is a rapid process occurring within 4 hours after corneal surgery.[7] The long-term use of preservatives in topical drops leads to epithelial apoptosis.[8,9] One example is benzalkonium chloride which, according to the concentration applied, can result in apoptosis or necrosis.[10] Apoptosis lies at the heart of corneal scar formation under these circumstances and is now a potential target for therapeutic intervention.[6] Dying cells that undergo the final stage of apoptosis are broken apart in several vesicles called apoptotic bodies. These are engulfed by phagocytes. This removal of dying cells occurs in an orderly manner without eliciting an inflammatory response.

In somatic cells, S1P prevents the activation of caspases exposed to analogues of ceramide.[11] Exogenous S1P can modulate cell proliferation, act on cytoskeletal remodeling and adhesion molecule expression, and inhibit apoptosis.[12] While ceramide is involved in stopping cell growth and apoptosis, S1P is, on the contrary, involved in proliferation and cell survival.[13] In fact, the dynamic balance between the intracellular concentration of ceramide and S1P has been proposed to be a biological sensor that determines whether the cell should live or perish.[14] Changes to this balance are current topics of research to stop or voluntarily induce apoptosis.

Premature menopause induced by irradiating female mice can be prevented by pre-treatment with S1P.[3] The same effect was observed with chemotherapy-induced apoptosis.[4] Spermatogenesis, in animal models, can also be protected from radiation-induced apoptosis by local injections of S1P.[5] Although the S1P action was known in a few tissues, its properties were not defined for the cornea. Its action on the eye was described for the retina. Retinal apoptosis during retinal detachment is associated with in vivo production of ceramide; S1P injected into the vitreous cavity can prevent the photoreceptor apoptosis.[15] However, in these studies, the SIP formulation was complex and unstable. We have developed an easier and more efficacious formulation for use. Thanks to its amphiphilic properties, the S1P can be dispersed in water in the presence of 10% Montanox 80, a surfactant. This simple formulation, stable at room temperature, can be applied topically. Corneal apoptosis is detectable very early in corneal keratocytes after Excimer laser treatment.[16] Moreover, some preservatives are important contributors to corneal inflammation and apoptosis.[17] Our novel formulation of S1P may prove to be useful in the prevention of these pathological responses.

Our studies show that a formulation, in which the active ingredient is S1P, can be achieved through its stable dispersion in a phosphate buffer in the presence of Montanox 80 (10%). We also demonstrate that the pre-treatment of a rabbit eye with S1P topical drops protects against early ethanol-induced corneal epithelial apoptosis, opening the door for a number of interesting therapeutic possibilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. T. Levade and Dr. H. Etchevers for constructive comments.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Creagh EM, Conroy H, Martin SJ. Caspase-activation pathways in apoptosis and immunity. Immunol Rev. 2003;193:10–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuvillier O, Andrieu-Abadie N, Ségui B, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Tardy C, Bonhoure E, et al. [Sphingolipid-mediated apoptotic signaling pathways] J Soc Biol. 2003;197:217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita Y, Perez GI, Paris F, Miranda SR, Ehleiter D, Haimovitz-Friedman A, et al. Oocyte apoptosis is suppressed by disruption of the acid sphingomyelinase gene or by sphingosine-1-phosphate therapy. Nat Med. 2000;6:1109–4. doi: 10.1038/80442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hancke K, Strauch O, Kissel C, Gobel H, Schafer W, Denschlag D. Sphingosine 1-phosphate protects ovaries from chemotherapy-induced damage in vivo. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otala M, Suomalainen L, Pentikäinen MO, Kovanen P, Tenhunen M, Erkkilä K, et al. Protection from radiation-induced male germ cell loss by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:759–67. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilgihan K, Konuk O, Hondur A, Akyürek N, Ozogul C, Hasanreisoglu B. Effect of topical vitamin E on ethanol-induced corneal epithelial apoptosis. J Refract Surg. 2005;21:761–3. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20051101-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helena MC, Baerveldt F, Kim WJ, Wilson SE. Keratocyte apoptosis after corneal surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:276–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baudouin C, Pisella PJ, Fillacier K, Goldschild M, Becquet F, De Saint Jean M, et al. Ocular surface inflammatory changes induced by topical antiglaucoma drugs: Human and animal studies. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:556–63. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Saint Jean M, Debbasch C, Brignole F, Rat P, Warnet JM, Baudouin C. Toxicity of preserved and unpreserved antiglaucoma topical drugs in an in vitro model of conjunctival cells. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20:85–94. doi: 10.1076/0271-3683(200002)20:2;1-d;ft085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuvillier O, Rosenthal DS, Smulson ME, Spiegel S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate inhibits activation of caspases that cleave poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and lamins during Fas- and ceramide-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2910–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel S, Cuvillier O, Edsall LC, Kohama T, Menzeleev R, Olah Z, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in cell growth and cell death. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;845:11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kester M, Kolesnick R. Sphingolipids as therapeutics. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:365–71. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, Vanek PG, Coso OA, Gutkind S, et al. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–3. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranty ML, Carpentier S, Cournot M, Rico-Lattes I, Malecaze F, Levade T, et al. Ceramide production associated with retinal apoptosis after retinal detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:215–24. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachtlin J, Langenbeck K, Schrander S, Zhang EP, Hoffmann F. Immunohistology of corneal wound healing after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 1999;15:451–8. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19990701-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debbasch C, Brignole F, Pisella PJ, Warnet JM, Rat P, Baudouin C. Quaternary ammoniums and other preservatives’ contribution in oxidative stress and apoptosis on Chang conjunctival cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:642–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debbasch C, Brignole F, Pisella PJ, Warnet JM, Rat P, Baudouin C. Quaternary ammoniums and other preservatives’ contribution in oxidative stress and apoptosis on Chang conjunctival cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:642–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]