Abstract

We report two cases of fulminant toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis following intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) administration. Case 1: A 42-year-old female received IVTA for presumed non-infectious panuveitis. Within 2 months, she developed diffuse macular retinochoroiditis with optic disc edema. Upon starting anti-toxoplasmic therapy (ATT), her intraocular inflammation resolved with catastrophic damage to the disc and macula. Case 2: A 30-year-old male received IVTA for presumed reactivation of previously scarred toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Despite simultaneous ATT, within 6 weeks, he developed extensive, multifocal macular retinochoroiditis. He continued to require ATT for 18 months and later underwent vitrectomy with silicone oil placement for severe epiretinal proliferation. Aqueous tap polymerase chain reactions were found positive for Toxoplasma gondii in both cases. In conclusion, IVTA administration can lead to fulminant toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis even when used with appropriate ATT. Extreme caution should be exercised while administering depot corticosteroids in eyes with panuveitis of unknown origin.

Keywords: Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide, retinochoroiditis, toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of intraocular inflammation in the world. Based on serologic evidence, it is estimated to affect up to one-half of the United States population.[1]

In ocular toxoplasmosis, the retina harbors cysts of Toxoplasma gondii in their dormant form. The antigens of T. gondii as well as the immune response of the host are known to modulate overall disease activity. A transient lapse in host immunity causes parasite multiplication and cyst wall rupture, producing the trademark unilateral focal lesion of necrotizing inner retinitis. A prolonged immune lapse can result in the fulminate spread of retinal necrosis. Conversely, an excessive immune response manifesting as severe vitreous and retinal vascular inflammation, though instrumental in restricting the organism's spread, results in the disease's characteristic symptoms of ocular pain, redness and blurred vision. This can result in healing by massive chorioretinal scarring, vitreous opacification, neovascular proliferation and retinal traction.[2] Reactivation often occurs contiguous to the scar.

Therapy targeting both the parasite and host immunity should be optimally balanced, as fulminant toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis has been known to occur in patients on oral corticosteroids alone.[3] The typical regimens include pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and prednisolone as triple therapy with an addition of clindamycin in quadruple therapy for at least 4–6 weeks.[4] Oral prednisone dosages, ranging from a daily maximum 20 mg to 1.0–1.5 mg/kg have been reported. The use of intravitreal or subtenon's depot corticosteroids has been considered an absolute contraindication by some investigators.[5] They believe that high-dose corticosteroids in close proximity to ocular tissues can potentially lead to unchecked retinal necrosis despite simultaneous anti-toxoplasmic coverage. We describe two cases of fulminant ocular toxoplasmosis following intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide (IVTA) administration.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 42-year-old Costa Rican female previously diagnosed with left eye autoimmune panuveitis presented with redness, pain and decreased vision to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (BPEI). After failing to respond to a course of oral prednisolone therapy, the patient received IVTA in the left eye in Costa Rica, 2 months prior to presentation. Her symptoms rapidly deteriorated following the injection.

With a 1-year past history of receiving 3-monthly infusions of mitoxantrone for multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosed 15 years back for neurological manifestations, she had also been treated with intravenous methylprednisolone intermittently for many years during MS exacerbations.

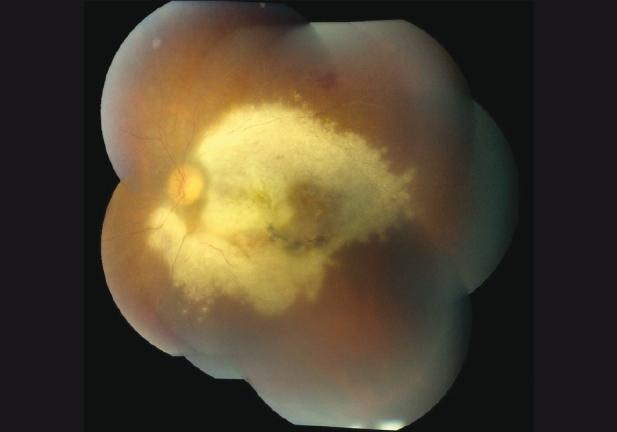

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in right eye and hand motions in left eye with a prominent afferent pupillary defect (APD). Left eye anterior segment revealed circumciliary congestion, “mutton-fat” keratic precipitates and moderate anterior chamber cells. Left eye posterior segment revealed moderate vitritis with suspended triamcinolone crystals, retinochoroiditis involving the entire macula and disc edema. Inferior macula showed a previous chorioretinal scar [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph of the posterior pole on presentation, Case 1

A presumptive diagnosis of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis was confirmed by an aqueous tap polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis for parasite antigen. IgG antibodies in high titers (250 IU) were present on serological assay. Within 2 months on oral double strength (DS) trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole twice daily and clindamycin 300 mg six hourly, vitreous inflammation resolved and the patient was left with a prominent macular scar, pale disc and BCVA of hand motions.

Case 2

A 30-year-old male presented to BPEI with decreased vision in the right eye for 4 months. During this interval, different community ophthalmologists treated him with various anti-toxoplasmic agents without improvement. He was given IVTA in the right eye 6 weeks prior to presentation and had worsened significantly since receiving the injection.

At presentation, the patient was on oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole DS twice daily and Clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours, as well as topical prednisolone acetate 1% hourly. The patient had been treated for right eye toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis 2 years back.

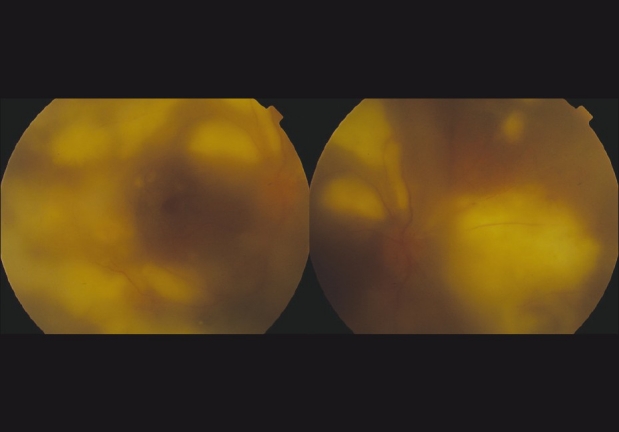

BCVA was 20/400 in right eye with an APD and 20/20 in left eye. Right eye anterior segment revealed uveitis similar to the former case. Right eye posterior segment revealed severe vitritis. Multifocal areas of retinitis were scattered throughout the posterior pole of the fundus, with several intraretinal hemorrhages in the mid-periphery [Fig. 2].

Figure 2.

Fundus photograph of the posterior pole on presentation, Case 2

The patient was diagnosed with fulminant recurrent toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis presumably exacerbated by IVTA. The diagnosis was confirmed by aqueous tap PCR. Oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole DS was replaced with clarithromycin 500 mg every 12 hours consequent to an allergic reaction to the former, while the rest were continued.

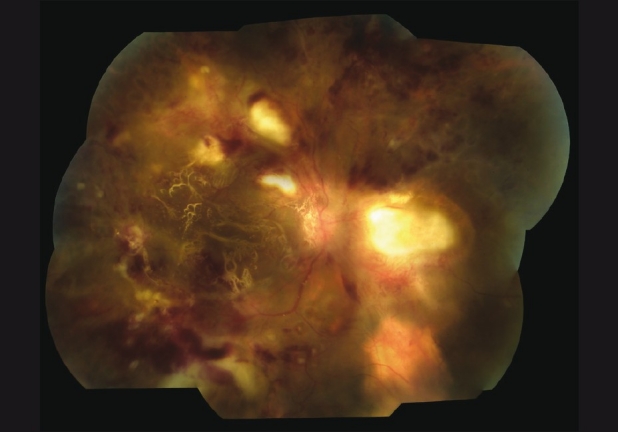

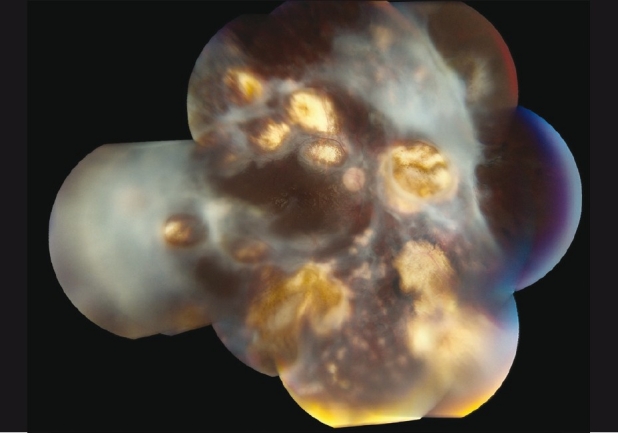

The patient then underwent pars plana vitrectomy with endolaser photocoagulation and silicone oil placement within a month for severe epiretinal neovascularization [Fig. 3]. Although initially improving to 20/80 with neovascularization regression, his retinitis persisted. After 18 months of anti-toxoplasmic therapy (ATT), the retinitis became inactive and his BCVA stabilized at 7/200 [Fig. 4].

Figure 3.

Fundus photograph of the posterior pole on 1-month follow-up, Case 2

Figure 4.

Fundus photograph of the posterior pole on 18-months follow-up, Case 2

Discussion

Recently, there has been an interest in the use of intravitreal corticosteroids as adjuncts in the treatment of severe ocular toxoplasmosis. Favorable outcomes in active toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis cases treated with intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone in four eyes and IVTA with oral anti-toxoplasmic agents in two eyes have been reported.[6,7]

However, tempering the positive outcomes described by these reports, Nobrega et al., reported a case of fulminant toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis following treatment with photodynamic therapy and IVTA for a presumed choroidal neovascular membrane with a devastating outcome similar to our first case.[8] This may be explained by the absence of appropriate anti-toxoplasmic coverage. However, Backhouse et al., described a case of fulminant toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis following IVTA despite simultaneous anti-toxoplasmic coverage, which led to a vitrectomy with silicone oil placement for cosmetic globe preservation similar to our second case.[9]

Given the high prevalence of toxoplasmosis in our patient population, it is prudent to strongly consider toxoplasmosis as an etiology for panuveitis before labeling it as autoimmune and proceeding with intravitreal corticosteroids, especially when the uveitis is unilateral. This can be accomplished by ordering serologic studies or by analyzing patient's aqueous humor by PCR when serologic studies are equivocal.[10]

Until the role of IVTA in the treatment of active ocular toxoplasmosis can be further elucidated, extreme caution should be exercised by the clinician.

References

- 1.Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment, Part I: epidemiology and course of disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:973–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins ES. Ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57:1–17. doi: 10.1136/bjo.57.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabates R, Pruett RC, Brockhurst RJ. Fulminant ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92:497–503. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engstrom RE, Jr, Hollang GN, Nussenblatt RB, Jabs DA. Current practices in the management of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:601–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor GR, Frenkel JK. Dangers of steroid treatment in toxoplasmosis. Periocular injections and systemic therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94:213. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910030093001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishore K, Conway MD, Peyman GA. Intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone for toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2001;32:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggio FB, Muccioli C, Belfort R., Jr Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide as an adjunct in the treatment of severe ocular toxoplasmosis. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:1080–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nóbrega MJ, Rosa EL. Toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis after photodynamic therapy and intravitreal triamcinolone for a supposed choroidal neovascularization: A case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70:157–60. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492007000100030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Backhouse O, Bhan KJ, Bishop F. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide as an adjunct in the treatment of severe ocular toxoplasmosis. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:1200–1. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montoya JG, Parmley S, Liesenfeld O, Jaffe GJ, Remington JS. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1554–63. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]