Abstract

Background:

Cervical cancer is one of the ten most frequent cancers in Turkey. It is well known that cervical cancer morbidity and mortality could be significantly reduced with an active cervical smear screening (Pap smear) program.

Aims:

The aims of this study were: 1) to evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of women about cervical smear testing; 2) to establish a cervical smear screening program and to evaluate the cervical cytological abnormalities that were found; 3) to determine the applicability, limitations and effectiveness of this screening in a primary health care unit.

Patients and Methods:

A total of 332 married women were included in our study. We collected data concerning socio-demographic and fertility characteristics, and knowledge about Pap smear testing was determined through printed questionnaires. A gynecological examination and Pap smear screening was performed on every woman in our study group.

Results:

Over ninety percent of our study group had never heard of and had not undergone Pap smear screening before. Of the 332 smears evaluated, 328 (98.8%) were accepted as normal, whereas epithelial cell anomalies were seen in 4 (1.2%), infection in 59 (17.7%), and reactive cell differences in 223 (67.2%) of the smears.

Conclusions:

The frequency of epithelial cell anomalies in our study group was less than the frequencies reported from Western countries. Knowledge regarding cervical cancer and Pap smear screening was very low. Pap smears can be easily taken and evaluated through a chain built between the primary health care unit and laboratory, and this kind of screening intervention is easily accepted by the population served.

Keywords: Cervical smear, cervical intraepithelial lesion, cervical cancer screening

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the seventh cancer in overall frequency, but the second most common cancer among women worldwide. An estimated 493,000 new cases and 274,000 deaths occurred from cervical cancer in the year 2002[1,2]. In general terms, cervical cancer is much more common in developing countries, where 83% of cases occur and where cervical cancer accounts for 15% of female cancers, with a risk before age 65 of 1.5%. In developed countries, cervical cancer accounts for only 3.6% of new cancers, with a cumulative risk (0 to 64) of 0.8%[3–5]. The estimated burden of neoplasia of the uterine cervix in the 27 EU member states sums up to 34,300 cases and 16,200 deaths. Romania, Lithuania and Bulgaria are the EU countries with the highest cervical cancer incidences and death rates[6].

According to official statistics the annual incidence of cervical cancer in the Republic of Turkey is 8 per 100,000[1]. In the year 2002, 4.9% of all cancers and 4.1% of all cancer deaths among women were due to cervical cancer[1]. In Turkey, cervical cancer is in the 8th most frequent cause of mortality and morbidity due to neoplasia in women. In the year 2007 the Ministry of Health of Turkey announced a cervical screening program (Pap smear testing) which will be integrated into routine primary health care services. The 6 key strategies of this prevention program for cervical cancer include the following: reaching a significant proportion of women in their 30s and 40s; using locally understood messages to increase the awareness of the disease; motivating women to get tested at once; making outpatient treatment widely available; arranging appropriate follow-up care; and evaluating the impact of the program on health outcomes.

This program has not begun yet, but training and education of the primary health care personnel, logistic support of the primary health care centers for Pap smear testing, and arrangements for the necessary follow-up procedures are proceeding. We hope that in the near future Pap smear testing will be a routine procedure throughout the primary health care system in the whole country.

The objectives of our study were as follows: 1) to evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of women about cervical smear testing; 2) to establish a smear screening program and to evaluate the cervical cytological abnormalities found; and 3) to determine the applicability, limitations and effectiveness of screening in a family medicine clinic.

Patients and Methods

Study participants

The study group included 332 married women who visited the Family Medicine Clinic in Bursa, Turkey. This clinic is a training center for medical students and serves as an outreach primary health care unit to a population of 10,000. Women who attended the clinic during a period of six months for various reasons were asked to participate to our study. Married women (currently or ever married), women without a hysterectomy, women without a history of any type of cancer, women who were not pregnant or who did not give birth recently were recruited. All the women were informed about the study and were asked to give their written consent. During the study period 443 women attended the clinic, of whom 27 were never married, 15 were pregnant, 9 gave birth recently, 2 had a history of cancer and 3 had had a hysterectomy. Thirty-eight women did not want to participate in the study. For these reasons a total of 94 women were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Uludag University.

Study instruments

In the first phase of the study, a questionnaire prepared by the authors was used to determine the women's socio-demographic and fertility characteristics, and the knowledge of the women regarding Pap smear testing. A total of 349 women answered the questionnaire. After the questionnaire was completed, women were invited to the family medicine clinic on a given date for Pap smear testing at the proper time of their menstrual cycle. The women were advised not to take a vaginal shower, have sexual intercourse, or use a tampon, gel or vaginal cream within 48 hours before coming to the clinic. Seventeen women did not come to their appointment, and were excluded from the study. The participation rate was 95.1%. In the second phase of the study, after a vaginal examination, cervical smears were taken from 332 women with a special endocervical brush. During the examination disposable speculums were used. All of the vaginal examinations were performed and all of the smears were taken by the same medical doctor who was trained for this procedure before the study. Smears were fixed with ethanol and sent to the laboratory at the end of every working day. The laboratory was accredited for cytological testing, and evaluations of the smears were made by a pathologist.

Cytologic tests

The conventional Pap smear test was used for cytology. The Pap smear has been the method of choice for cervical cancer screening since the 1950s, proving valuable for mass screening and enabling detection of lesions early enough for effective treatment[7]. The Pap smear has some limitations, however. The most important are its limited sensitivity, which is between 47-62%, and the subjective interpretation of the results[7]. On the other hand, Pap smear testing also has strengths, such as wide acceptance, meeting most of the criteria for a good screening test in settings with adequate resources, obtaining a permanent record of the test in the form of a slide, and having a high specificity of 60-95%[7]. Evaluation of the cervical cells was done using the Bethesda System 2001 as follows:

-

1)

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy

-

a)Organisms

- Trichomonas vaginalis

- Fungal organisms morphologically consistent with Candida spp.

- Shift in flora suggestive of bacterial vaginosis

- Bacteria morphologically consistent with Actinomyces spp.

- Cellular changes consistent with Herpes simplex virus.

-

b)Other non-neoplastic findings

- Reactive cellular changes

- Atrophy

-

a)

-

2)

Epithelial cell abnormalities

-

a)Squamous cell

-

Atypical squamous cells

- Of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

- Can not exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

- Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) encompassing: human papilloma virus (HPV)/mild dysplasia/CIN 1

- High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) encompassing: moderate and severe dysplasia, CIS/CIN 2 and CIN3 with features suspicious for invasion (if invasion is suspected)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

-

-

b)Glandular cell

- Atypical

- Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ

- Adenocarcinoma

-

a)

-

3)

Other malignant neoplasms

Statistical analyses

Socio-demographic data obtained in the first phase of the study and Pap smear results were recorded and statistical analyses were made with the SPSS V.11.0 program (SPSS Inc., Chicago ILL). Frequency distributions, descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were calculated. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Data are reported as mean values ± standard deviation.

Results

Socio-demographic and fertility characteristics:

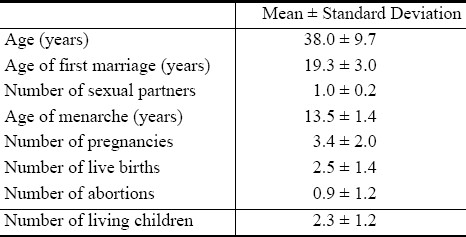

The mean age of the women in the study group was 38.0 ± 9.7 years. Most of the participants (96.4%) reported that they had one sexual partner during their lifetime, while 3.6% reported that they had two partners. Their educational attainments were as follows: 19.6% illiterate, 64.2% primary school, 14.7% high school and 1.5% university graduated. Most of the participants (93.7%) were housewives.

About 2/3 of the women reported that they had regular menses, while 19% reported they had irregular menses, and 14.8% reported that they were in menopause. The mean number of pregnancies for the women in the study group was 3.4 ± 2.0, but 4.5% of the study group had never had a pregnancy. Twenty-four percent of the participants said that they were not using any contraceptive method currently, while 37.3% were using a modern method and 38.7% a traditional method. The most commonly used contraceptive method was CI (coitus interruptus) (38.3%), followed by IUD (intrauterine device) (16.3%), condom (9.6%) and sterilization (5.4%).

Most women reported they had never smoked (73.5%), whereas 20.2% had smoked irregularly and 6.3% had quit smoking. Seventy-seven percent of participants reported no familial history of any type of cancer.

The percent of the participants who had never heard of Pap smear screening and had never undergone testing was 90.7%. Thirty-one women had one previous Pap smear screening. The reported results of the previous Pap smear screenings were as follows: normal (13); infection (15); malignancy (1); unknown (2). The socio-demographic and fertility characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and fertility characteristics of the participants

Vaginal examination and Pap smear

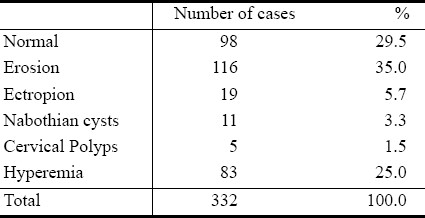

Before the vaginal examination and Pap smear the participants were asked about their gynecological complaints. According to their reports 12% had no complaints, 30% had one, 29% two, 19% three, and 10% more than three complaints. The most often reported complaint was vaginal discharge, followed by itching and lower genital tract burning. The results of the vaginal examination are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Vaginal examination results

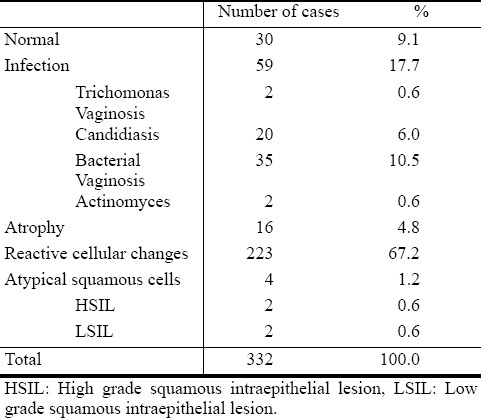

Of the 332 Pap smears, 9.1% were found to be normal, while 17.7% were evaluated as infection, 4.8% as atrophy, 67.2% showed reactive cellular changes and 1.2% as atypical squamous cells. Details of the Pap smear results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pap smear results

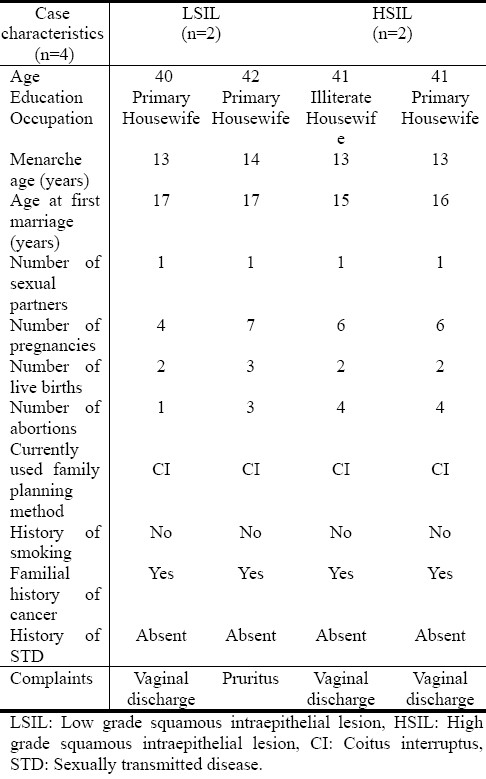

We found no statistically significant relationship between age, number of births, currently used family planning method and having reactive cellular changes or infection. The number of women with atypical squamous cells were inadequate (n=4) to perform a statistical analysis. Some characteristics of the participants with atypical cell changes are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Some characteristics of participants with atypical epithelial cell changes

The study group was not familiar with Pap smear testing; 91% had never heard of it. We found no statistically significant relationship between their knowledge and age (χ2 =1.251, P>.05) or educational attainment (χ2 =2.982, P>.05).

Discussion

Our Pap smear results showed a low rate of atypical cervical epithelial cell abnormalities among our study population. However, these results should be regarded cautiously due to the low sensitivity of Pap smear testing. We have not had the opportunity to evaluate our results with other more sensitive tests like AAT (acetic acid test) and HPV identification[8].

A few studies have been performed among Turkish women using the Pap smear test, and have also found low rates of atypical cervical cells. A hospital-based study between 1997 and 1999 among 24,178 women reported atypical cell abnormalities as 0.4%[9]. Another study among 3,013 women reported a frequency of atypical cell abnormalities of 1%[10]. A recent study done in a hospital setting found a frequency of atypical cells of 0.7%, but the frequency of cervical HPV colonization was 2.1%[11]. Another hospital-based study with 4487 patients reported the prevalence of LSIL as 4.2% and HSIL as 2.8%[12].

Studies in primary health care settings gave also low frequencies of atypical cell abnormalities of 1.7%[13] and 5.3%[14]. In our study the majority of Pap smears were evaluated as reactive cellular changes (67.2%), followed by infections (17.7%). Similar results were obtained from other studies done both in hospital or primary health care settings: 45% reactive cellular changes and 13.0% infections[9]; 23.4% reactive cellular changes and 50.6% infections[10]; 42.9% reactive cellular changes and 26.0% infections;[14] and 28.9% reactive cellular changes and 49.8% infection[13]. These results show that vaginal infections are important and may be a public health problem that should receive more attention.

The low frequency of atypical epithelial cell abnormalities in our study could be due to a low-risk population. Risk factors for cervical cancer are as follows[15]: persistent or chronic infection with oncogenic types of HPV (types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 58); immunodeficiency; high parity; tobacco smoking; coinfection with HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases; and long term (>5 years) use of oral contraceptives. The status of Turkish women according to these risk factors has been reported in some published reports.

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one published study in regarding the HPV infection prevalence among Turkish women[11]. This study reported a low general frequency (2.1%) of cervical HPV colonization. Forty-eight percent of HPV-positive cases were infected with types 16, 18 and 31 which are accepted as oncogenic variants. This study suggested that HPV infection with oncogenic types is not very common among Turkish women. There are insufficient data about immunodeficiency and HIV infection prevalence in Turkey, but the latest official statistics showed a low prevalence of HIV infection and AIDS cases. The total number of cases reported in the year 2008 was 2,412, of whom 750 were women, in a population of 73,000,000[16].

High parity is common in Turkey, and according to the Turkey Demographic and Health Survey 2003, the total fertility rate was 2.2 per thousand. Among our study group the mean number of pregnancies was 3.4 ± 2.0 and of live births was 2.5 ± 1.4 which could be considered high parity[6].

Cigarette smoking is a growing problem among Turkish women and studies have shown that about 40% - 50% percent of women were regular smokers[17]. Among our study group this percentage was 20.2%.

Oral contraceptives are not widely used by Turkish women, and only 4.7% of all married women of childbearing age use oral contraceptives[17]. In our study group the use of oral contraceptives was found to be 3.6%, which could be evaluated as low risk.

We conclude that among Turkish women the risk factors for cervical cancer are high parity, cigarette smoking and vaginal infections. In spite of these existing risk factors, studies both in hospital and primary health care settings have shown a low prevalence of atypical cervical cell changes. Modifying factors for risk should be further evaluated and other factors such as cultural characteristics, sexual patterns and sociological aspects should be taken into account. Some published studies have showed that circumcision and having only one sexual partner may have a negative impact on developing cervical cancer by decreasing the risk of HPV infection[18,19]. However, in men with low-risk sexual behavior and monogamous female partners, circumcision makes no difference to the risk of cervical cancer[20]. Menczer quotes research that male circumcision probably does not contribute to a lower incidence of cervical cancer in Jewish populations[21]. Since circumcision is a traditional and religious pattern among the Turkish population, all the husbands of the study group women were circumcised. Following culture and tradition, 96.4% of the women had had only one sexual partner, and all of the sexual partnerships were marital. Could all these patterns be linked with the low prevalence of atypical cervical cell abnormalities? These relationships should be further evaluated.

In our study, 90.7% of the study participants reported that they had not heard about Pap smears before. In previous studies, the percentages of women who had heard of Pap smear testing were reported to be 29.7% and 76.9%[22,23].

Conclusions

Although the relatively small size of our study group may have been a limitation, we believe that this study reveals some important issues. In conclusion we want to emphasize some key points.

Our study and other studies performed among Turkish women found a low prevalence of atypical epithelial cell changes, and cervical cancer among Turkish women has a lower morbidity and mortality compared to most developed countries. However, the risk of developing cervical cancer still exists among Turkish women. A high prevalence of genital infections and insufficient knowledge about HPV infection and its serotypical distribution could be a burden for controlling cervical cancer in the future.

Knowledge regarding cervix cancer and Pap smear testing appears to be very poor.

Pap smears can be easily taken and evaluated through a chain built between a primary health care unit and laboratory, and this kind of testing is easily accepted by the population being served. We followed up with 95% of our study group.

The cost of the Pap smear test was as low as $20 per test in our study and was covered by all the health insurance schemes that exist in Turkey. Service in all primary health care units is free of charge; no additional costs were accrued, and there were no transportation costs because the primary health care unit where the specimens were taken was within walking distance of the laboratory.

The announcement by the Ministry of Health that envisions Pap smear testing as a routine screening at primary health care units should be a reality in the very near future. This application will not only help prevent cervical cancer but will also create an opportunity for educating women and their husbands regarding this health issue.

Acknowledgments

Author's contributions

H. Celik-Mehmetoglu: planning and design of the study, the questionnaire, data acquisition process, interpretation of the results, drafting of the article and final approval.

G. Sadikoglu: planning and design of the study, presentation of results, critical revision of the content and final approval.

A. Ozcakir: planning and design of the study, critical revision of the article and final approval.

N. Bilgel: design of the study, preparation of the manuscript and final approval.

This study and manuscript has no conflict of interests.

The authors would like to acknowledge the editorial assistance of Dr. Belinda Peace.

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN 2000 database versión 1.0. IARC. 2002. (Accessed December 5, 2009, at http://www-dep.iarc.fr/globocan.database.pdf .

- 2.Ghim S, Poasu PS, Jenson AB. Cervical cancer: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment and future vaccines. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2002;3:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanta V, Krishnamurthi S, Gajalakshmi CK, Swaminathan R, Ravichandran K. Epidemiology of cancer of cervix: Global and national perspective. J Indian Med Assoc. 2000;98:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biennial report (2000-2001) Lyon: IARC; 2001. WHO/IARC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbyn M, Autier P, Ferlay J. Burden of cervical cancer in the 27 member states of the European Union: estimates for 2004. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(8):1423–1425. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planning and Implementing Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Programs: A Manual for Managers. Seattle: AACP; 2004. AACP -Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cronjé HS. Screening for cervical cancer in the developing world. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19(4):517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firat P, Mocan G, Sezgin Y, Karayazgan Y, Kilic T, Salici H. Three years experience in a university hospital review of 24,178 cases. Cytopathol. 2000;11:369. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuncer R, Uygur D, Kis S, et al. Pap smear results of Ankara Zubeyde Hanim Maternity Hospital in 1999 and 2000: analysis of 3,013 cases. MN Klinik Bilimler & Doktor. 2003;9(1):94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inal MM, Kose S, Yildirim Y, et al. The relationship between human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraephitelial neoplasia in Turkish women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(6):1266–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pata O, Polat A, Tok E, et al. Clinical importance of ASCUS and AGUS classification according to the Bethesda system. J Turkish German Gynecol Assoc. 2003;4(3):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isikli B, Ozalp S, Oner U, et al. Pap smear screening among married women living in Osmangazi University ALPU training area. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:60–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oner S, Demirhindi H, Erdogan S, Tuncer I, Akbaba M. Gynecologic examination findings and pap smear screening results of women in Dogankent, Turkey. TJPH. 2004;2(2):85–91. (Accessed March 17, 2009, at http://www.hasuder.org/file/TJPH_v2n2.pdf. ) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comphrensive Cervical Cancer Control. A Guide to Essential Practice. Geneva: WHO; 2006. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS- Turkey. HIV (+) & AIDS cases in Turkey. (Accessed August 12, 2009, at http://www.unaidsturkiye.org. )

- 17.Hacettepe University Institute of Population Studies, Ministry of Health General Directorate of Mother and Child Health and Family Planning, State Planning Organization and European Union. Ankara: 2004. Turkey Demographic and Health Survey, 2003. (Accessed March 12, 2009, at http://www.hips.hacettepe.edu.tr/tnsa2003eng/reports.htm. ) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1052–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castellsagué X, Bosch X, Muñoz N, Meijer CJLM, Shah KV, de Sanjosé S, et al. Male circumcision, penile human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1105–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivet C. Circumcision and cervical cancer is there a link? Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1096–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menczer J. The low incidence of cervical cancer in Jewish women: has the puzzle finally been solved? Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akyuz A, Guvenc G, Yavan T, Cetinturk A, Kok G. Evaluation of the Pap smear test status of women and of the factors affecting this status. Gulhane Med J. 2006;48:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirin A, Atan SU, Tasci E. Protection from cancer and early diagnosis applications in Izmir, Turkey: A pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(3):207–213. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]