Abstract

Painless obstructive jaundice is often associated with a malignant disease of the common bile duct or head of the pancreas. The authors present a unique case of a 62-year-old woman affected by an intrahepatic cystadenoma that extended into the common biliary duct. To our knowledge no previous case reports have been published on similar cases. After undergoing an en-block hepatic and bile duct resection, this patient is doing well without signs of recurrent disease.

Background

Cystadenomas are uncommon benign cystic neoplasms of the biliary system, of unknown aetiology and account for approximately 5% of all the hepatobiliary cystic masses.1 Most cystadenomas arise within the intrahepatic bile ducts.2 3 Very rarely these lesions are found in the extrahepatic biliary system and gallbladder.4

Women are more commonly affected with a mean age at presentation of 45 years.4 Preoperative diagnosis is challenging, since the radiologic features are non-specific.

We present a rare case of biliary cystadenoma with both intra and extrahepatic bile duct involvement. The literature on the radiologic and pathologic features of biliary cystadenomas, as well as approach to management, will be discussed.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old woman with a remote history of breast cancer and hypothyroidism presented to her primary care physician with 1 week history of dysuria and hyperpigmentation of her urine. Her physical examination was within the normal limits except for sclero-icterus. Thyroid replacement hormone therapy was the only medication she was on and her family and social history were non-contributory.

Investigations

Her physical examination was unremarkable. Liver function tests were abnormal, with an alkaline phosphatase of 215 U/l (normal: 32–92 U/l), aspartate aminotransferase of 266 U/l (normal: 15–41 U/l), alanine aminotransferase of 433 U/l (normal: 14–54 U/l), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase of 524 U/l (normal: 7–50 U/l) and a total bilirubin of 19 μmol/l (normal: 0–16 μmol/l). Carbohydrate antigen (CA19.9) 19–9 levels were within normal limits.

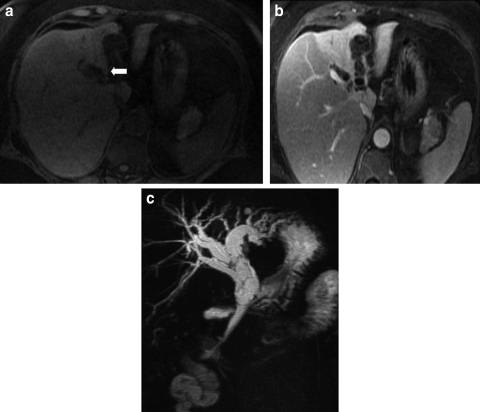

Contrast enhanced CT scan and MRI with pancreatography (MRCP) were performed and demonstrated diltation of the left intrahepatic, common hepatic and common bile ducts. The presence of enhancing septations within these ducts was demonstrated on MRI (figure 1A–C). In addition, the left hepatic lobe was atrophic and its parenchyma was hyperattenuating on CT (figure 2) with increased T2 signal on MRI.

Figure 1.

(A) Ultrafast gradient echo image shows dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts in the left lobe of the liver (arrow), with fine, hyperintense septations within the affected bile ducts. (B) Ultrafast gradient echo image, acquired 10 min post gadolinium administration, shows enhancement of the septations within dilated intrahepatic bile ducts. There is differential enhancement of the right and left hepatic lobes. The left hepatic lobe is atrophic due to chronic biliary obstruction. (C) Coronal projection MR angiogram shows dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts and common bile duct, with thin septations seen bile ducts.

Figure 2.

Axial portal-venous-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan shows dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts in the left hepatic lobe. There are subtle, fine septations within the dilated ducts. The left hepatic lobe is atrophic and there is differential enhancement of the hepatic lobes.

An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) did not demonstrate a communication between the biliary system and the cystic tumour. Cytopathology specimens obtained from brushings during ERCP were negative for malignancy.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for an intraductal, multi-cystic mass includes:

-

▶

hydatid cyst

-

▶

biliary cystadenocarcinoma

-

▶

and intraductal papillary mucinous tumour (IPMT).

Treatment

On laparotomy, atrophy of the left hepatic lobe and dilatation of the common hepatic duct were appreciated. An extended left hepatectomy, with common bile duct excision and Roux-en-Y right intrahepatic biliary-enteric anstomosis, was performed.5

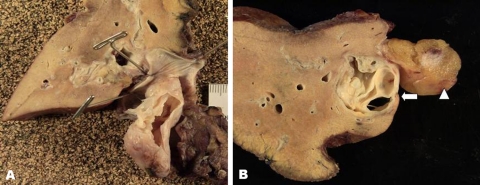

The gross examination of the surgical specimen demonstrated a multi-cystic, mucin-containing mass arising in the left hepatic duct that prolapsed into the common bile duct (figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

(A) Photograph of the resected left hepatic lobe and mass. The common bile duct has been opened. The intraductal mass prolapses through the common bile duct. A incision has been made in the mass and the internal septations are evident. (B) Photograph of the resected left hepatic lobe and mass shows a multi-septated mass within a dilated left intrahepatic bile duct (arrow). The round ligament can be seen adjacent to the dilated bile duct (arrowhead).

Outcome and follow-up

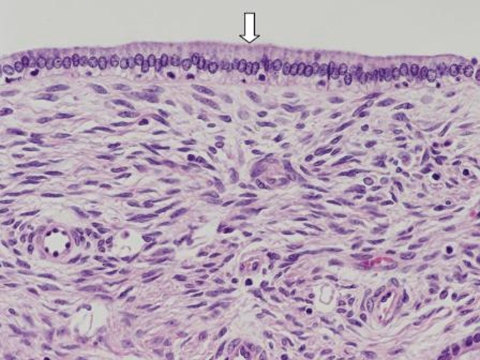

Microscopically, the cysts were lined with a single layer of mucinous columnar to cuboidal epithelium (figure 4). The stroma proliferating beneath the epithelium was composed of spindle cells, resembling ovarian stroma. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for oestrogen receptors and weakly positive for progesterone receptors. These findings were consistent with a biliary cystadenoma with ovarian-type stroma.

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of the resected mass shows a layer of columnar epithelium lining the mass (arrow), and the presence of ovarian-type stroma deep to the epithelial layer.

After more than 2-year follow-up postresection, the patient has been doing well, without any evidence of recurrence and with normalisation of her liver enzymes and serum total and direct bilirubin levels.

Discussion

The most common presenting symptoms in patients with cystadenomas are abdominal discomfort and pain.1 2 6–9 Other reported symptoms include jaundice, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, intolerance to fatty food and occasionally cholangitis.1 2 6–8

A summary of the more salient clinical and diagnostic characteristics of biliary cystoadenomas is reported in table 1. Rarely, a biliary cystadenoma is discovered incidentally during radiological investigations for other reasons.8 10 Liver function tests may be abnormally elevated.9 Elevated levels of serum CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) have been reported; however, this is a variable finding.9

Table 1.

Summary of clinical, haematological and radiological characteristics of cystoadenoma of the biliary ducts

| References | Clinical variables | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1–3,6–8 | Symptoms | Jaundice, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, intolerance to fatty food, cholangitis |

| 9 | Haematological tests | Elevated total bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP |

| 9 | Serum tumour markers | Occasional elevated Ca 19.9 and or CEA |

| 1,2,4,11,12 | Endoluminal tumour markers | Levels of Ca 19.9 and CEA might be elevated in the fluid aspirated from the lumen of the cysts |

| 4 | Radiological findings: CT | Multi-loculated, multi-septated intrabiliary neoplasms. Average size at the time of diagnosis=15 cm. On CT scan, the content of the cyst is usually hypoattenuating. Calcifications within the cyst walls and septation have been described. Possible irregular wall enhancement |

| 10 | Radiological findings: MRI | T1 and T2 signal intensity of the intracystic fluid can be variable depending on the protein concentration and presence or absence of blood |

| 6 | Histology | Presence of cysts lined with mucinous cuboidal or columnar epithelium. Ovarian-type stroma present in 85% of cases, exclusively in females |

| 16 | Differential diagnosis | Hydatid cyst, biliary cystoadenocarcinoma, intraductal papillary mucinous tumour (IPMT) |

| 2–4,6,9–11,18 | Natural history | Malignant transformation into cystoadenocarcinoma or sarcoma has been described. Cystoadenomas with ovarian-type stroma have better prognosis |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate amino transferase; CA 19.9, carbohydrate antigen 19.9; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

Histologically, cystoadenomas are characterised by the presence of cysts lined with mucinous cuboidal or columnar epithelium.6 An ovarian-type stroma is seen in 85% of cases and exclusively in females.4 A marsupial pseudocapsule separates the cystadenoma from the biliary epithelium.4 Elevated levels of CA 19-9 and/or CEA have been reported within the cysts themselves.1 2 4 11 12

Although the biliary cystadenoma is a benign entity, malignant transformation can occur, leading to cystadenocarcinoma.4 Sarcomatous transformation has also been described in one case.6 It has been suggested that cystadenocarcinomas arising from biliary cystadenomas with ovarian-type stroma have a relatively indolent course, whereas cystadenomas without ovarian-type stroma have a poorer prognosis.4

Most commonly, on radiologic imaging, these neoplasms appear as multi-loculated, multi-septated intrabiliary neoplasms. They are usually large at the time of presentation, with a mean tumour size of 15 centimetres.4 On CT, the intralesional content is usually hypoattenuating.

On MRI, the T1 and T2 signal intensity of the intracystic fluid can be variable, depending on the protein concentration and the presence or absence of blood products.10 But typically, as with any fluid containing mass, biliary cystadenomas are low signal on T1 and high signal on T2.13 There may be enhancement of the septations and cyst walls.2 7 14 Calcifications within the cyst walls and septations have been also reported by some authors.13 15

Irregular wall enhancement and the presence of papillary projections have been described and these findings should increase suspicion for biliary cystadenocarcinoma.13 14 Other unusual features include multiple masses, prolapse into the common duct and communication with a large intrahepatic duct.15

MRCP is helpful in evaluating the extent of disease, and can provide a roadmap of the bile ducts proximal to the lesion before surgical interventions, since these are often incompletely opacified on ERCP.10

Differential diagnosis for an intraductal, multi-cystic mass includes: hydatid cyst, biliary cystadenocarcinoma and intraductal papillary mucinous tumour. Certain clinical and radiologic findings can be helpful in differentiating a cystadenoma from these entities. For example, negative serologic testing and the absence of a peripheral eosinophilia can help exclude a hydatid cyst. An IPMT usually demonstrates communication with the bile ducts, a finding not typically seen with a biliary cystadenoma.16 Thus, dilatation of bile ducts distal to the tumour favours a diagnosis of a biliary IPMT.16 Also, it has been suggested that an IPMT is more likely to have prominent papillary excresences or mural nodularity16 and a prominent solid component with irregular enhancement raises the suspicion for a biliary cystadenocarcinoma1 2 13 14 17 that can be radiologically confirmed by the presence of lymphadenopathy and metastases.14 Unfortunately, due to the often non-specific imaging features of the biliary cystadenoma, accurate preoperative diagnosis is extremely challenging.

Although biliary cystadenomas are benign neoplasms, complete resection is advised as preoperative diagnosis is often questionable, as well as the risk of malignant transformation into cystadenocarcinoma or sarcoma is significant.2–4 6 9–11 18 There is a very high recurrence rate in incompletely resected biliary cystadenomas,1 2 6 7 and in those simply treated with aspiration, sclerosis, drainage, internal Roux-en-Y drainage or marsupialisation.8 Therefore excision, through partial hepatic resection, or complete enucleation is advised in all patients suitable for surgery.2 7 8 11 Enucleation must be approached cautiously due to the possibility of distortion of surrounding vascular structures and possible attachment to the Glissonian sheath.1 8

In order to improve the preoperative diagnostic specificity and decrease operative risks, a treatment algorithm has been recently proposed for patients with suspected biliary cystadenomas.11 The algorithm includes cyst aspiration to measure CEA and CA19-9 levels, and cyst wall biopsy whenever possible.11 The feasibility and usefulness of this algorithm needs to be validated by further studies and the current recommendation remains complete surgical resection whenever there is radiological suspicion of this condition.

Learning points.

-

▶

Biliary cystoadenomas are very rare tumours mostly affecting the intrahepatic ducts.

-

▶

Preoperative differential diagnosis with malignant cystoadenocarcinoma is very challenging.

-

▶

Surgical resection is recommended as biliary cystadenomas can degenerate in cystoadenocarcinomas and sarcomas.

-

▶

Ovarian-type stromal histological type is associated with better prognosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Mitchell P, et al. Cystadenomas of the liver: a spectrum of disease. Can J Surg 2001;44:371–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delis SG, Touloumis Z, Bakoyiannis A, et al. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: a need for radical resection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;20:10–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim K, Choi J, Park Y, et al. Biliary cystadenoma of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1998;5:348–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. A light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:1078–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pang YY. Brisbane 2000 terminology of liver anatomy and resections. HPB 2000;2:333–39 HPB (Oxford) 2002;4: 99–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voltaggio L, Szeto OJ, Tabbara SO. Cytologic diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma during intraoperative consultation: a case report. Acta Cytol 2010;54(5 Suppl):928–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz de Liano A, Olivera E, Artieda C, et al. Intrahepatic mucinous biliary cystadenoma. Clin Transl Oncol 2007;9:678–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas KT, Welch D, Trueblood A, et al. Effective treatment of biliary cystadenoma. Ann Surg 2005;241:769–73; discussion 773–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gadzijev E, Ferlan-Marolt V, Grkman J. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinoma. Report of five cases. HPB Surg 1996;9:83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin M, Mourra N, Honigman I, et al. Assessment of MRI and MRCP in diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. Eur Radiol 2006;16:407–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koffron A, Rao S, Ferrario M, et al. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: role of cyst fluid analysis and surgical management in the laparoscopic era. Surgery 2004;136:926–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas JA, Scriven MW, Puntis MC, et al. Elevated serum CA 19-9 levels in hepatobiliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma. Two case reports with immunohistochemical confirmation. Cancer 1992;70:1841–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortelé KJ, Ros PR. Cystic focal liver lesions in the adult: differential CT and MR imaging features. Radiographics 2001;21:895–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seidel R, Weinrich M, Pistorius G, et al. Biliary cystadenoma of the left intrahepatic duct (2007: 2b). Eur Radiol 2007;17:1380–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kehagias DT, Smirniotis BV, Pafiti AC, et al. Quiz case of the month. Biliary cystadenoma. Eur Radiol 1999;9:755–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim JH, Jang KT, Rhim H, et al. Biliary cystic intraductal papillary mucinous tumor and cystadenoma/cystadenocarcinoma: differentiation by CT. Abdom Imaging 2007;32:644–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veroux M, Fiamingo P, Cillo U, et al. Cystadenoma and laparoscopic surgery for hepatic cystic disease: a need for laparotomy? Surg Endosc 2005;19:1077–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson SW, Kruskal JB, Kane RA. Benign hepatic tumors and iatrogenic pseudotumors. Radiographics 2009;29:211–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]