Abstract

Fibroid most commonly presents in the reproductive age group and presence of fibroid with postmenopausal bleeding is a rare entity and all investigations and measures should be done to rule out leiomyosarcoma. A 45-year-old female had attained menopause 3 year back and developed postmenopausal bleeding since 2 months, with palpable mass, of 24 weeks size. Ultrasonography showed multiple whorled mass lesions, endometrium and myometrium could not be seen separately. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingoophorectomy was performed. Intraoperative findings showed 24 weeks uterine mass with size 17.5×15.5×11.5 cm and weight 1.9 kg with multiple, intramural fibroids. Cut section of removed specimen showed black and yellow necrotic and haemorrhagic areas with degenerative changes suggestive of malignancy. Histopathology reported epithelioid leiomyosarcoma.

Background

Leiomyosarcoma is a relatively rare form of cancer, comprising between 5 and 10% of soft tissue sarcomas, which are in themselves relatively rare.1 2 Leiomyosarcomas can be very unpredictable. They can remain dormant for long periods of time and recur after years. It is a resistant cancer, meaning generally not very responsive to chemotherapy or radiation. The best outcomes occur when it can be removed surgically with wide margins early, while small and still in situ. Uterine epithelioid leiomyosarcoma is an unusual smooth muscle neoplasm. It is distinguished on cytoarchitectural grounds from the majority of leiomyosarcomas that arise in the uterus.3 After excluding carcinosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma has become the most common subtype of uterine sarcoma. However, it accounts for only 1–2% of uterine malignancies. Most occur in women over 40 years of age who usually present with abnormal vaginal bleeding (56%), palpable pelvic mass (54%) and pelvic pain (22%).4 Signs and symptoms resemble those of the far more common leiomyoma and preoperative distinction between the two tumours may be difficult. Nevertheless, malignancy should be suspected by the presence of certain clinical behaviours, such as tumour growth in menopausal women who are not on hormonal replacement therapy.5 Occasionally, the presenting manifestations are related to tumour rupture (haemoperitoneum), extra-uterine extension (one-third to one-half of cases), or metastases. Only very rarely does a leiomyosarcoma originate from a leiomyoma. We report a case of epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of uterus.

Case presentation

A 45-year, para 3, presented with heavy postmenopausal bleeding since 2 days. She has attained menopause 3 years back. Her menstrual history was normal. Her general examination was normal. Abdominal examination revealed 24 weeks size uterine mass with well-defined margins and bosselated surface without any tenderness. It was mobile from side to side. Cervix was deviated to left side and pulled upwards. Clinically it was diagnosed as fibroid uterus with query malignant potential.

Investigations

Ultrasonography revealed enlarged uterus with multiple whorled mass lesions, largest of size 8.6×7.1 cm, not extending into the abdomen and pelvis, normal adnexa, endometrium and myometrium could not be seen separately. Blood group was B positive, haemoglobin-11.3 g%, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine-33.4%, total leucocyte count-7900 cu.mm, platelet count 279×103/μl, prothrombin time-16.5 s. Chest x-ray and ECG were normal.

Differential diagnosis

-

▶

Uterine fibroid with sarcomatous degeneration

-

▶

Endometrial stromatosis.

Treatment

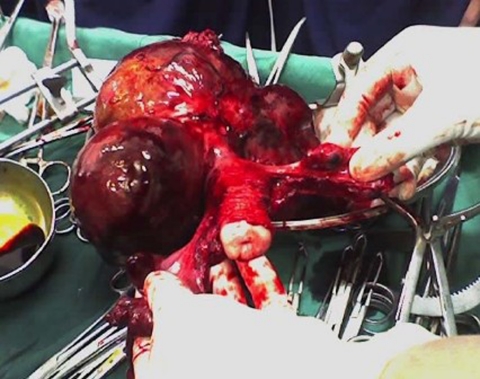

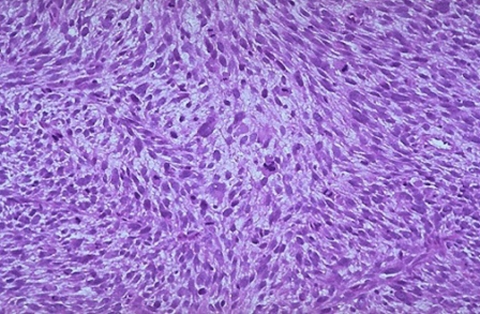

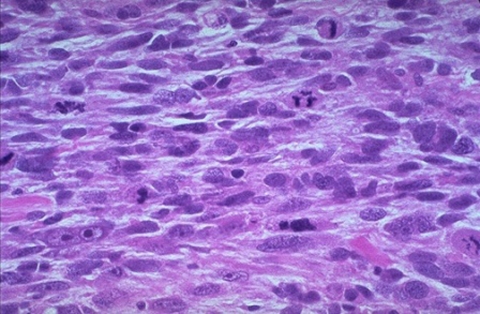

Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingoophorectomy was performed under general anesthesia. Intraoperative findings showed 24 weeks uterine mass with size 17.5×15.5×11.5 cm and weight 1.9 kg with multiple, intramural fibroids (figure 1). Cut section of removed specimen showed black and yellow necrotic and haemorrhagic areas with degenerative changes suggestive of malignancy (figure 2). Abdominal cavity was palpated for any secondaries or lymphadenopathy but it revealed no abnormality. Postoperatively she received one unit of blood transfusion and injectable antibiotics (third generation cephalosporins and metronidazole) for 2 days. Postoperative period was uneventful. Low power (10x) histopathology reported leiomyoma with sarcomatous degeneration (figure 3). With high power microscopy (100x) epithelioid leiomyosarcoma with more than 10 mitosis per 10 was seen (figure 4). CT scan abdomen and pelvis, done on 10th postoperative day was normal. She was discharged with necessary follow-up advice on 14th postoperative day.

Figure 1.

Postoperative specimen of the enlarged uterus.

Figure 2.

Cut section of the specimen: size 17.5×15.5×11.5 cm, weight-1.9 kg multiple, intramural fibroids. Black and yellow necrotic and haemorrhagic areas.

Figure 3.

Low power microscopy of the specimen showing leiomyoma with sarcomatous degeneration.

Figure 4.

High power microscopy showing epithelioid leiomyosarcoma with more than 10 mitosis per 10 high power fields.

Outcome and follow-up

She reported on 30 June 2011 and is asymptomatic.

Discussion

Uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS) are a rare and aggressive form of uterine cancer as compared with the more common endometrial carcinomas and are associated with a poorer prognosis. ULMS tumours account for approximately 1% of patients with uterine cancer with an estimated annual incidence of 0.64 per 100 000 women.6 7 ULMS are of high metastatic potential with 5-year overall survival rates varying between0 and 73%.8 9 ULMS occur primarily in women 40 to 60 years of age. The most frequent presenting symptoms are abnormal vaginal bleeding and pelvic or abdominal pain. The amount of bleeding ranges from spotting to menorrhagia and is often associated with foul-smelling vaginal discharge. Less common symptoms include weight loss, weakness, lethargy and fever. On pelvic examination, the uterus is often enlarged, and in some cases part of the tumour may prolapse through the cervical os and into the vaginal canal. Diagnosis is usually not made before surgery, thus many patients present with advanced disease. The rarity of these tumours has prevented the performance of large epidemiological studies to identify risk factors. Data regarding parity, onset of menarche, or age at menopause as risk factors are inconclusive.

Uterine leiomyosarcoma is an extremely uncommon cancer that affects as few as seven adult women in a million. The 5-year survival rates for women who are diagnosed in Stage I of the disease is around 50 to 65 per cent.10 11 If the disease is more advanced at the time of diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate for uterine leiomyosarcoma drops to 0 to 20 per cent. The poor prognosis is largely due to two factors, the high incidence of recurrence and the ease with which the disease can spread to other organs of the body through the blood and lymphatic systems.

The histopathologic diagnosis of uterine leiomyosarcoma is usually straight forward since most clinically malignant smooth muscle tumours of the uterus show the microscopic constellation of hyper cellularity, severe nuclear atypia, and high mitotic rate generally exceeding 15 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields (MF/10 HPF).12 13 Finally, mitotic count was also a significant factor in the subset of 97 stage I uterine LMSs, along with period and menopausal status in the study by Larson et al. Moreover, one or more supportive clinicopathologic features such as peri- or postmenopausal age, extra uterine extension, large size (over 10 cm), infiltrating border, necrosis and atypical mitotic figures are frequently present. Epithelioid and myxoid leiomyosarcomas, however, are two rare variants which may be difficult to recognise microscopically as their pathologic features differ from those of ordinary spindle cell leiomyosarcomas. In fact, nuclear atypia is usually mild in both tumour types and the mitotic rate is often 3 MF/10 HPF. In epithelioid leiomyosarcomas, necrosis may be absent and myxoid leiomyosarcomas are often hypo cellular. In the absence of severe cytologic atypia and high mitotic activity, both tumours are diagnosed as sarcomas based on their infiltrative borders.14 The minimal pathological criteria for the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma are more problematic and, in such cases, the differential diagnosis has to be made, not only with a variety of benign smooth muscle tumours that exhibit atypical histologic features and unusual growth patterns.

Very few cases are reported in the literature. Similar studies have been reported by Toyoshima et al15 whereby they observed a massive vaginal bleeding from a cervical tumour in a Japanese woman. A total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed. Histological findings led to a diagnosis of epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the uterine cervix. The patient underwent adjuvant chemotherapy and has been disease-free for over 20 months.16 Wang et al recently reported clinical pathological parameters such as tumour cell necrosis and lymphovascular invasion as the presenting symptom of epithelioid leiomyosarcoma and reviewed 27 cases (17 spindled, 5 epithelioid, 2 myxoid and 3 mixed) of leiomyosarcomas.16

The best chance for a cure is an isolated LMS tumour that was surgically excised with wide, clear margins, while it was small. Even some of these patients have recurrences or metastases, though the ‘still clear’ rate may be as high as 80 or 90% at 5 years. A larger, high-grade tumour is much more likely to recur or metastasise. The rate of recurrence or metastasis may be as high as 80% or more for these tumours. With a metastasis, if you can have it surgically excised with wide, clear margins, you may again have a chance for a cure. However, you are likely to get more metastases. If you are c-kit positive,17 if you respond to STI-571, choice is chemotherapy. Doxorubicin, the chemotherapeutic agent that is most successful against LMS so far, is not that successful. About 30% of the patients will experience a partial success rate. A very, very few may go into what looks like complete remission. The rest will not respond to doxorubicin. And the response does not last that long (months). Doxorubicin is also very toxic to heart, bone marrow and liver. Its cardio toxicity is so powerful, that there is a lifetime dosage of doxorubicin that must not be exceeded. Presently, in the literature, chemotherapy regimens containing doxorubicin are the chemotherapeutic choices with the highest response rates.18 There are, however, other choices of agents, and many clinical trials of other treatments going on.

Learning points.

-

▶

A uterine epitheliod leiomyosarcoma is a rare malignant (cancerous) tumour that arises from the smooth muscle lining the walls of the uterus (myometrium). Leiomyosarcoma is a form of cancer.

-

▶

The exact cause of leiomyosarcoma, including uterine leiomyosarcoma, is unknown. Leiomyosarcomas require a high index of clinical suspicion because uterine fibroid in a postmenopausal female complaining of per vaginum bleeding and abdominal distension is very rare and difficult to judge on basis of clinical examination.

-

▶

The 5-year survival rates for women who are diagnosed in Stage I of the disease is around 50 to 65 per cent. If the disease is more advanced at the time of diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate for uterine leiomyosarcoma drops to 0 to 20 per cent.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of my Rural Medical College, loni for all there support, Dr Dilip Bhavthankar for all his guidance, Dr Venkatramani, Principal, Rural Medical College for allowing me to present this case in Stanley Medical College, Chennai.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Norris HJ, Zaloudek CJ. Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. In: Blaustein A, ed. Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. Second Edition New York: Springer; 1982:352 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver MJ, Abraham JA. Leiomyosarcoma of the bone and soft tissue: a review. Electronic sarcoma update newsletter 2007;4 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buscema J, Carpenter SE, Rosenshein NB, et al. Epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Cancer 1986;57:1192–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Angelo E, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas: a review. Gynecol Oncol 2010;116:131–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perri T, Korach J, Sadetzki S, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: does the primary surgical procedure matter? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:257–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harlow BL, Weiss NS, Lofton S. The epidemiology of sarcomas of the uterus. J Natl Cancer Inst 1986;76:399–402 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartsich EG, Bowe ET, Moore JG. Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. A 50-year review of 42 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1968;32:101–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurman RJ, Norris HJ. Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. VI. Epithelioid smooth muscle tumors including leiomyoblastoma and clear-cell leiomyoma: a clinical and pathologic analysis of 26 cases. Cancer 1976;37:1853–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appleman HD, Helwig EB. Gastric epithelioid leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma (leiomyoblastoma). Cancer 1976;38:708–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livi L, Paiar F, Shah N, et al. Uterine sarcoma: twenty-seven years of experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;57:1366–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Major FJ, Blessing JA, Silverberg SG, et al. Prognostic factors in early-stage uterine sarcoma. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 1993;71(4 Suppl):1702–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaloudek CJ, Norris HJ. Mesenchymal tumors of the uterus. In: Fenoglio CM, Wolff M,eds. Progress in Surgical Pathology. Vol. 3 New York: Masson; 1981:1–35 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans HL, Chawla SP, Simpson C, et al. Smooth muscle neoplasms of the uterus other than ordinary leiomyoma. A study of 46 cases, with emphasis on diagnostic criteria and prognostic factors. Cancer 1988;62:2239–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkins K, Bell S, Kempson M, et al. Myxoid smooth muscle tumors of the uterus. Modern Pathol 2001;14:132A [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toyoshima M, Okamura C, Niikura H, et al. Epithelioid leiomyosarcoma of the uterine cervix: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:957–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang WL, Soslow R, Hensley M, et al. Histopathologic prognostic factors in stage I leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: a detailed analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:522–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rushing RS, Shajahan S, Chendil D, et al. Uterine sarcomas express KIT protein but lack mutation(s) in exon 11 or 17 of c-KIT. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Cearbhaill R, Hensley ML. Optimal management of uterine leiomyosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2010;10:153–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]