Abstract

Objective:

We examined the effectiveness of a 2-month-long home-based cognitive retraining program together with treatment as usual (TAU; psychoeducation and drug therapy) on neuropsychological functions, psychopathology, and global functioning in patients with first episode schizophrenia (FES) as well as on psychological health and perception of level of family distress in their caregivers.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-five FES patients were randomly assigned to either treatment group receiving home-based cognitive retraining along with TAU (n=22) or to control group receiving TAU alone (n=23). Patients and caregivers received psychoeducation. Patients and one of their caregivers were assessed for the above parameters at baseline, post-assessment (2 months) and at 6-months follow-up assessment.

Results:

Of the 45 patients recruited, 12 in the treatment group and 11 in the control group completed post-intervention and follow-up assessments. Addition of home-based cognitive retraining along with TAU led to significant improvement in neuropsychological functions of divided attention, concept formation and set-shifting ability, and planning. Effect sizes were large, although the sample size was small.

Conclusions:

Home-based cognitive retraining program has shown promise. However, further studies examining this program on a larger cohort with rigorous design involving independent raters are suggested.

Keywords: Cognitive retraining, first-episode schizophrenia, psychoeducation, global functioning, psychopathology

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is characterized by cognitive deficits present in several cognitive domains in the prodromal, symptomatic, and chronic stages.[1–4] Cognitive deficits and negative symptoms impair social functioning, work performance, and community functioning.[5–10]

Cognitive retraining has emerged as a treatment modality to reduce cognitive deficits, with the expectation that improvement of cognition would result in clinical improvement as well as improvement of psychosocial functioning.[11,12] Meta-analytic studies have shown moderate to large effect sizes.[13–15] Cognitive retraining studies till date have been carried out in chronic schizophrenia patients, with only a handful of studies examining remediation of cognitive deficits in early phase of the illness.[16–19]

Although cognitive deficits are known to exist prior to the onset of illness, only four studies with randomized control design have examined the effect of cognitive retraining in the early phase of the illness with mixed results.[16–19] Eack et al.[16] compared cognitive enhancement therapy (CET) with enriched supportive therapy (EST). Wykes et al.[17] examined the 3-month long cognitive remediation therapy (CRT). Ueland and Rund[18] and Delahunty et al.[20] studied the effect of a 30-hour cognitive remediation program. Only two of the above four studies have found clinically significant change after cognitive retraining.[16,17] In both studies, improvement occurred in the targeted cognitive functions and social functioning, with reduction of negative symptoms. The results have shown that instituting cognitive remediation early in the course of the illness benefits the patient.

These programs were carried out in hospital setting by a therapist. Longer durations combined with frequent hospital visits would increase treatment costs and limit wider application. The high cost of treatment combined with the hassle of daily hospital visits makes treatment adherence difficult in cognitive retraining. Hence, there is a need to develop a cognitive retraining program which is easy to implement and inexpensive. A home-based cognitive retraining program may be the answer as it eliminates daily hospital visits, making it user friendly. The reduction in costs due to reduced staff costs in the hospital and the reduction of travel cost to the patient might enable a longer duration of treatment at a lower cost.

The present study was carried out with an aim to develop a cognitive retraining program targeting a range of cognitive functions known to be impaired in schizophrenia. It was also aimed to make this cognitive retraining program home based, with a minimum level of monitoring by a family member. Such a program would reduce the financial and personal burden of visiting the hospital frequently. The intervention program would then be a cost-effective treatment for schizophrenia. The efficacy of the program in first-episode schizophrenia patients was tested by comparing it with routine treatment given in our hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample consisted of 45 patients with an International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) diagnosis of schizophrenia in the first episode of illness. Based on the clinical history and clinical examination, diagnosis as per the ICD-10 criteria was made by the resident psychiatrist, and concurred by the consultant psychiatrist. Duration of illness was less than 2 years. Patients spoke English or Kannada or Hindi fluently, had adequate visual and hearing ability, and had minimum education up to 5th grade. Patients with a diagnosis of mental retardation, presence of neurosurgical conditions or neurological condition other than schizophrenia, and those who had undergone electroconvulsive therapy in the past 6 months were excluded. One member who was identified as patient's primary caregiver (parent/spouse/sibling/relative) living with the patient for at least the past 6 months and actively involved in taking care of the patient, not having any current psychiatric illness, was included in the study. The research study was approved by the National Institute's ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from the patients as well as the caregivers.

Assessment of patients

Psychopathology profile of patients was obtained using the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).[21] Disability in overall functioning was assessed using the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule-II (WHODAS-II).[22] The neuropsychological tests administered were: Digit Vigilance test,[23] Color Trails test,[24] Triads test[25] to assess attention; finger tapping test[26] to assess motor speed; Digit Symbol Substitution[27] to assess mental speed; Token test[28] to assess verbal comprehension; Animal Names test,[23] verbal N-back – Task,[29] Stroop test,[25] Tower of London,[30] Wisconsin card sorting test (WCST)[31] to assess various executive functions; Rey's auditory verbal learning test (RAVLT)[32] to assess verbal learning and memory and Rey Osterrieth complex figure test (CFT)[33] to assess visuo-constructive ability and visual memory.

The scores on the neuropsychological tests were compared with norms appropriate to that of the subject's gender, age, and education. Indian norms for the tests in the neuropsychological battery have been developed based on literacy [illiterates, school educated (1st to 10th std), and college educated (11th std and above)], age [young adults (16–30 years), middle-aged adults (31–50 years), and older adults (51–65 years)], and sex (males and females). In each of the above intersections of gender × age × education, 30 normal volunteers were tested. Percentile scores were calculated for each test variable in each of the above intersection groups.[25] The 15th percentile score (1 SD below the mean) was taken as the cut-off score.[34] Whether the patient had paid fulltime or part-time employment or was not at all employed was also noted.

Assessment of caregivers

The caregivers were assessed based on general General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28)[35] and the Scale for Assessment of Family Distress (AFD).[36] GHQ-28 was used to measure the overall psychological health. The Likert scoring method of 0–1–2–3 with a threshold score of 39/40 was used. The AFD is a self-rating scale for assessment of family distress experienced due to an ill member in the family. The scale has a list of 25 different behaviors and option for allowing caregivers to mention any other behavior causing distress. The severity of distress was captured on a 5-point rating scale. The symptoms were grouped under four categories, viz., activity related, self-care related, aggression related, and depression related. The severity of distress was measured using a 5-point rating scale (0=no distress, 1=minimal distress, 2=moderate distress, 3=marked distress, and 4=intense distress).

Design

The study used a randomized controlled design. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly allocated to either the treatment group or the control group. The experimental group received a 2-month home-based cognitive retraining program along with treatment as usual, which included drug treatment and psychoeducation. Control group received treatment as usual (drug treatment and psychoeducation). Both groups received three sessions of psychoeducation. The tests / tools were administered to patients and caregivers at baseline (prior to the intervention), post-assessment (after the intervention), and at 6-month follow-up (4 months after completion of the intervention). The first author SH assigned the patients to the two groups using random allocation method. She carried out the assessment of patients and caregivers as well as conducted the psychoeducation sessions.

Intervention

Home-based cognitive retraining program

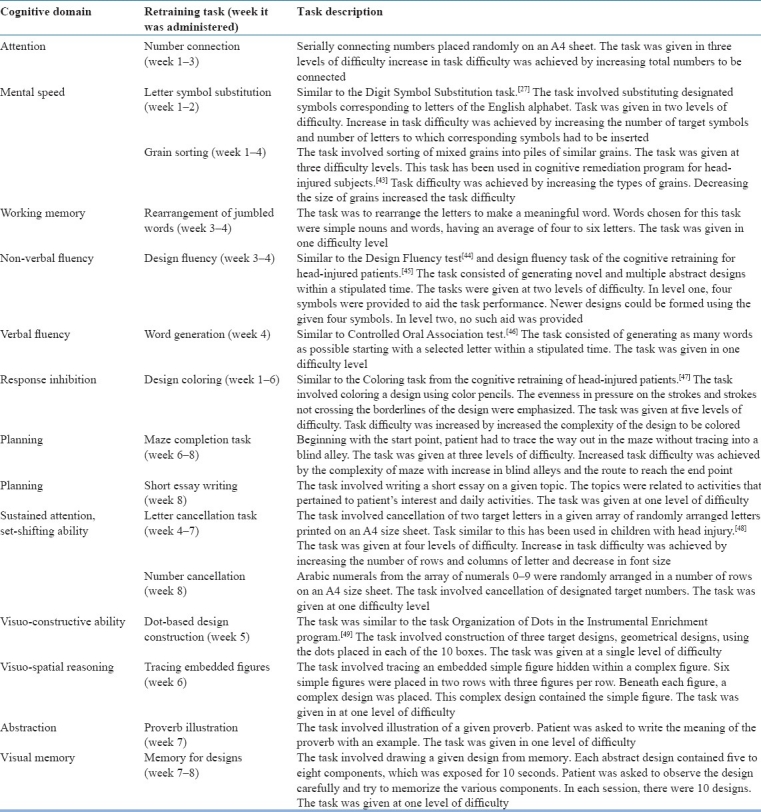

The tasks in the retraining program were presented in a graded fashion. The task difficulty increased gradually as the retraining program progressed. The program included tasks that could be performed by the patient in the home setting, with a minimum level of monitoring by the caregiver. A brief description of the cognitive retraining tasks and domains targeted has been given in Table 1.

Table 1.

A brief description of the home-based cognitive retraining program

The program consisted of two sets which were printed in a booklet form. Tasks for week 1-4 were given in Set 1, while those for week 5–8 were given in Set 2. The patient was given Set 1 after the baseline assessment. Set 2 was given to the patient 1 month later. In each set, the tasks for each week were marked separately using a color marker. The number of tasks to be carried out each day was also designated. The patient and caregiver were instructed on how to perform each task. The task was also demonstrated. The patient was instructed to note the time taken to complete each task. Based on the instructions given, the caregiver was asked to monitor the session without being over involved or punitive.

After the initiation of the home-based cognitive retraining program, the researcher met the patient and caregiver twice, once after completion of 4th week and the second time after completion of 8th week. The researcher reviewed the performance on the retraining program during this meeting. Completion of two-thirds of the tasks given for each week was considered as adequate compliance. The caregiver and patient were asked to telephone the researcher to clarify doubts at any time during the retraining.

Psychoeducation session

As per the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines for treating schizophrenia patients,[37] psychoeducation was provided to all patients along with medication. Three psychoeducation sessions at pre-assessment, 1-month follow-up, and post-assessment were held with the caregivers and the patients in both groups. Each session lasted 45 minutes to 1 hour. The psychoeducation session gave information regarding the nature of diagnostic symptoms, prevalence, average age of onset, course of the illness, nature of positive and negative symptoms, types of cognitive deficits, and importance of positive feedback and emotional support by the caregivers.

Adherence to treatment (home-based cognitive retraining program)

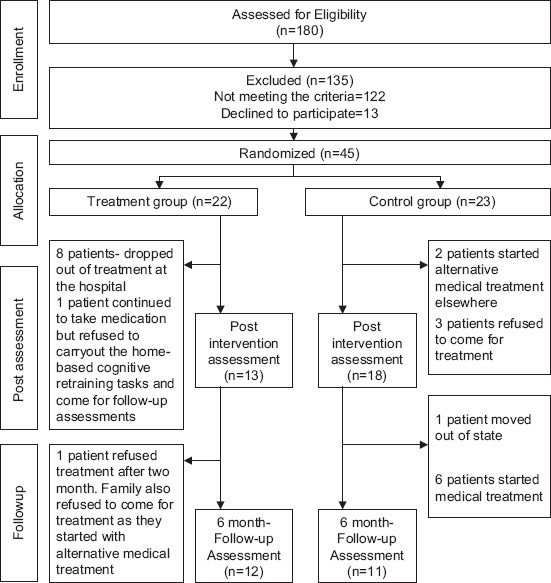

Of the 22 patients who were recruited into the treatment group, 13 completed the 2-month home-based cognitive retraining program [Figure 1]. All patients completed minimum of two-thirds of the retraining program. The least adhered to and completed task was the short essay writing task and the proverb illustration task, which only 7 of 13 patients completed. The performance on each of the cognitive retraining tasks was measured quantitatively, such as time taken to complete the task or errors committed or total correct responses. Two tasks – the short essay writing task and illustration of proverb task – were assessed qualitatively.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients recruited in the present study

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patient group

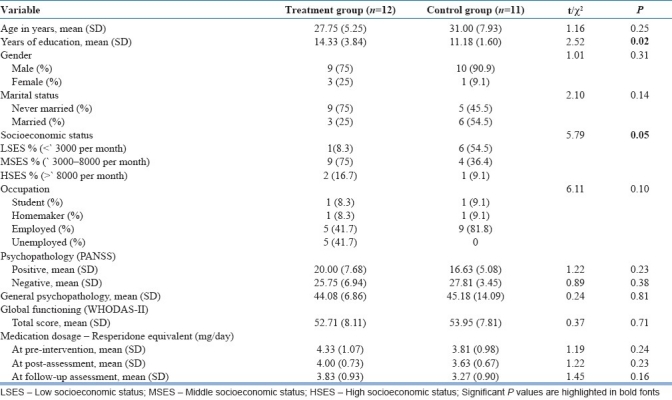

A total of 45 patients and their caregivers were enrolled in the study. Twenty-two patients were randomized to the treatment group and 23 to the control group. Figure 1 depicts the sample allocation details and dropout of patients in treatment and control groups at post-intervention and follow-up assessments. The socio-demographic and clinical details of the patients who completed the study are depicted in Table 2. Analysis of data was carried out on the patients who completed the follow-up assessment (n=12 in treatment group, n=11 in control group). The two groups did not differ in the clinical variables of duration of illness, distribution of subtypes of schizophrenia, and symptomatology or level of overall functioning. However, the treatment group had better education and socioeconomic status than the control group.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and clinical details of the patient group

In the treatment group, 58.3% of patients were in gainful employment and the rest were unemployed. In the control group, all were in gainful employment.

Variables which were skewed logarithmic transformations were performed to normalize data prior to analyses. The two groups were compared on all variables at baseline using t-test (Bonferroni correction employed). At baseline, the two groups did not differ in the neuropsychological test scores, level of general psychopathology, and global functioning.

Characteristics of the caregivers’ group

In the treatment group, 66.7% were males with an average age of 39.00±10.41 years and a mean education of 12.75±3.93 years. The relation was parent 33.3%, spouse 16.7%, siblings 41.7%, and others 8.3%. In the control group, 45.5% were males with an average age 36.18±13.45 years and a mean education of 9.00±2.44 years. The relation was parent 45.5%, spouse 45.5%, and sibling 9.1%.

Effect of intervention on patients – Cognitive functions, psychopathology and global functioning

The treatment and control groups were compared across the three time points with the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (with education as a covariate) using the statistical package for the social sciences version 15.0. The dependent measures in patients were scores on the neuropsychological tests, severity of psychopathology, and level of global functioning. The dependent measures in the caregivers were measures of general health and level of family distress. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated to measure the extent of improvement due to treatment.

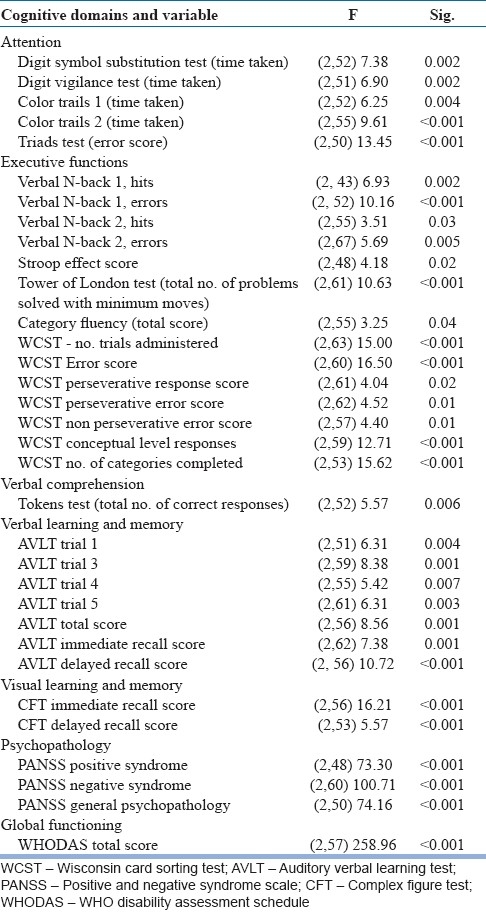

The significant treatment effect showed that treatment as usual improved neuropsychological variables mental speed (finger tapping test), sustained attention (Digit Vigilance test), focused attention (Color Trails 1 and 2), divided attention (Triads test), category fluency (Animal Names test), verbal working memory (verbal N-back 1 and 2), response inhibition (Stroop test), planning (Tower of London test), concept formation and set-shifting ability (WCST), verbal learning and memory (AVLT), visual learning and memory (CFT), global functioning (WHODAS-II), and decrease in positive syndrome, negative syndrome, and general psychopathology - PANSS from the baseline assessment to post-assessment as well as from post-assessment to follow-up assessments [Table 3].

Table 3.

Treatment effect – Shows the variables on which treatment effect was significant

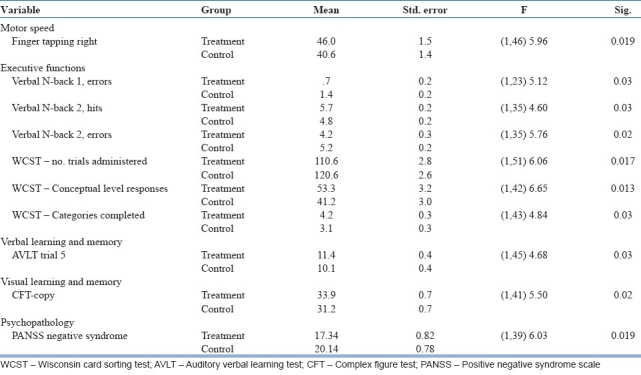

In addition, the significant group effects showed that cognitive retraining improved cognition and reduced negative symptoms. As shown in the group effect (two groups compared across three time points) and by the post hoc comparisons, the treatment group had significantly lesser negative symptoms and better performance in the neuropsychological tests assessing motor speed (finger tapping right hand), verbal working memory (verbal N-back 1 and N-back 2), concept formation and set-shifting ability (WCST), verbal learning (AVLT), and visuo-constructive ability (CFT-copy) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Group effect – Showing the variables on which the two groups were significantly different

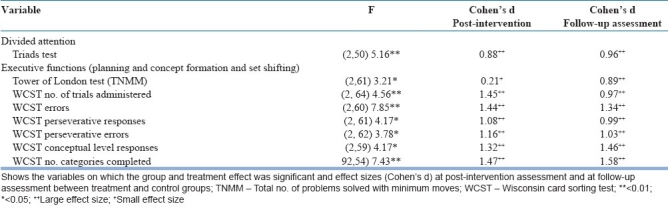

The group × treatment effect showed that treatment group had significant improvement in the neuropsychological domains of divided attention (Triads test), planning (Tower of London test), concept formation and set-shifting ability (WCST) in the experimental group. The effect sizes between the treatment and control groups were large in the post-assessment and follow-up assessment, with one exception. This was the total number of problems solved with minimum moves in the Tower of London test, where the effect size was small [Table 5]. The interaction effect on global functioning or psychopathology was not significant.

Table 5.

Interaction effect (group × treatment)

Effect of intervention on caregivers – Psychological health, family distress

The group effect and the interaction effects were nonsignificant on the measures of psychological health and perception of level of family distress between the caregivers of the two groups.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study which has developed and examined the effect of home-based retraining program in first-episode schizophrenia patients. The significant interaction effect has shown that addition of cognitive retraining to treatment as usual led to improvement in executive functions such as divided attention, planning, concept formation and set-shifting ability, following treatment. The large effect sizes indicate the improvement to be substantial. Further, the improvement sustained for 6 months even though treatment had ceased. The improved cognition in the treatment group cannot be attributed to practice on the neuropsychological tests as the control group also underwent the pre-, post- and follow-up assessments. Supplementing the interaction effect is the group effect which has shown better motor speed, verbal working memory, concept formation and set-shifting ability, verbal learning, and visuo-constructive ability. Since the two groups were comparable at baseline on the above functions, the significant group effect may be attributed to the effect of intervention.

Several factors could have played a role in the improvement observed. First, cognitive functions were targeted employing the bottom-up method. Basic cognitive functions such as attention and mental speed were targeted in the initial phase of the retraining program, followed by higher-order cognitive functions such as planning and set-shifting ability later in the program. Secondly, tasks were arranged in increasing level of task difficulty, thereby not taxing the patient unduly, and facilitated learning. Thirdly, improvement in executive functions may have had a cascading effect on improving other functions such as motor speed, verbal learning, and visuo-constructive ability. Fourthly, the very fact that patient was made to feel less “patient-like” by placing the responsibility of carrying out cognitive retraining by himself/herself with very minimal involvement by the caregiver may have enhanced motivation. Also, the gradual increase in difficulty would have helped to sustain motivation to perform the tasks. Medalia and Choi[12] have highlighted the fact that motivation mediates adherence and improvement in cognitive functions via cognitive remediation programs.

The present study also found a reduction in negative symptoms as seen by the group effect similar to the findings by Wykes et al.[17] The observed decrease in negative symptoms may be attributed to the improvement in executive functions. Negative symptoms are associated with poor executive functions.[38,39] The present results found improvement in seven functions of which four (divided attention, concept formation and cognitive flexibility, verbal working memory, planning) were executive functions. Goal-directed behavior is improved by executive functions.[40] It may be hypothesized that improved executive functions improved goal directedness which was reflected as reduced negative symptoms.

The additional improvements noted above, attributable to cognitive retraining, have not included further improvements of global outcome. Addition of cognitive retraining may have resulted in changes in global functioning which may not have been picked up during the interview and assessment carried out using the WHODAS.

Improvement in measures of psychological health and family distress did not differ significantly between the groups following intervention. The caregivers in the present sample had probably not reached the level of distress that is generally observed in chronic illness group. When a patient and caregiver visit hospital in the initial phase of the illness, the family has little knowledge of the causes, symptoms, and management of the illness. Tolerance will be high toward changes in patient's behavior and symptoms. It is known from previous studies that improved caregivers’ knowledge about the illness leads to decrease in relapse and rehospitalization.[41,42] The increased knowledge gained through psychoeducation may have improved the psychological health as well as resulted in decrease in perceived level of distress.

The present study had significant dropout of patients from recruitment period to follow-up assessment period. Patients who dropped out of treatment either started medical treatment elsewhere or refused to come for treatment. Refusal of treatment could reflect family members’ difficulty in accepting the diagnosis of the illness or avoidance of stigma attached with a diagnosis of psychiatric illness or stigma associated with visiting a tertiary mental hospital where the study was carried out.

This study had several limitations such as small sample size, significant dropout, and absence of independent rater who was blind to the allocation of patients to the two groups. Using a quantitative method to measure even subtle changes in global functioning and occupational functioning could have added to the strength of the study. In spite of these limitations, the 2-month-long home-based cognitive retraining program has improved cognitive functions and decreased negative symptoms. Increasing the duration of the home-based retraining program and combining it with other social skills’ training program may improve cognition, clinical functioning, and overall functioning further.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Bilder, Goldman R, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, et al. First-episode schizophrenia: Characterization and clinical correlates. Neuropsychological Trends. 2007;2:7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, Reiter G, Bell L, Bates JA, et al. Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: Initial characterization and clinical correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:549–59. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg W. The course of cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia. In: Sharma T, editor. Cognition in Schizophrenia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rund BR, Melle I, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Midboe LJ, et al. The course of neurocognitive functioning in first-episode psychosis and its relation to premorbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis, and relapse. Schizophr Res. 2007;91:132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanello A, Perrig L, Huguelet P. Cognitive functions related to interpersonal problem-solving skills in schizophrenia patients compared with healthy subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2006;142:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penades R, Boget T, Catalan R, Bernardo M, Gasto C, Salamero M. Cognitive mechanisms, psychosocial functioning, and neurocognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:219–27. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryson G, Bell MD. Initial and final work performance in schizophrenia: cognitive and symptom predictors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:87–92. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000050937.06332.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green MF. Cognitive impairment and functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disoder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 9):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medalia A, Choi J. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:353–64. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9097-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Bellack AS. A review of cognitive training in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:359–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtz MM, Seltzer JC, Shagan DS, Thime WR, Wexler BE. Computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: What is the active ingredient? Schizophr Res. 2007;89:251–60. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Cooley SJ, DiBarry AL, Montrose DM, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia: Effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1468–76. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.11.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wykes T, Newton E, Landau S, Rice C, Thompson N, Frangou S. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007;94:221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueland T, Rund BR. A controlled randomized treatment study: The effects of a cognitive remediation program on adolescents with early onsetpsychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:70–4. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueland T, Rund BR. Cognitive remediation for adolescents with early onset psychosis: A 1-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delahunty A, Reeder C, Wykes T, Newton E, Morice R. Revised manual for cognitive remediation for executive functioning deficits. London: South London and Maudsley NHS Trust; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. WHODAS II. [Last accessed on 2002]. website (available from: http://wwwwhoint/icidh/whodas/ )

- 23.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological assessment. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Elia LF, Satz P, Uchiyama CL, White T. Color trails test. U S A: Psychological assessment resources Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao SL, Subbakrishna DK, Gopukumar K. NIMHANS Neuropsycholoy Battery-2004. Bangalore: NIMHANS Publication; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, norms and commentary. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wechsler D. WAIS-R manual. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Renzi E, Vignolo LA. The token test: A sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain. 1972;85:665–78. doi: 10.1093/brain/85.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith EE, Jonides J. Storage and executive processes in the frontal lobes. Science. 1999;283:1657–61. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shallice T. Specific Impairments of Planning. Philosophical transactions of Royal Society of London. 1982;13:199–209. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milner B. Effects of different brain lesions on card sorting. Arch Neurol. 1963;9:90–100. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maj M, Satz P, Janssen R, Zaudig M, Startace F, D’Elia LF, et al. WHO Neuropsychiatric AIDS study, cross sectional phase II: Neuropsychological and neurological findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:51–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyers J, Meyers K. Rey Complex Figure and Recognition Trial: Professional Manual. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heaton RK, Grant I, Butters N, White DA, Kirson D, Atkinson JH. The HNRC500-neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1:231–51. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9:139–45. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gopinath PS, Chaturvedi SK. Measurement of distressful psychotic symptoms perceived by the family: Preliminary findings. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:3435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guidelines for Treatment of Schizophrenia. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2004. APA. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heydebranda G, Weiserb M, Rabinowitzc J, Hoff A, DeLisie LE, Csernansky JG. Correlates of cognitive deficits in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuepbach D, Keshavan MS, Kmiec JA, Sweeney JA. Negative symptom resolution and improvements in specific cognitive deficits after actute treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;53:249–61. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ylvisaker M, Szekeres SF, Feeney TJ. Cognitive Rehabilitation: Executive Functions. In: Ylvisaker M, editor. Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation: Children and Adolscents. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leff J. Working with the families of schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(Suppl, 23):71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cassidy E, Hill S, O’Callaghan E. Efficacy of a psychoeducational intervention in improving relatives’ knowledge about schizophrenia and reducing rehospitalisation. Eur J Psychiatry. 2001;16:446–50. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra A. Neuropsychological rehabilitation in head injury: Home based approach. Bangalore: NIMHANS, Bangalore University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones-Gotman M, Milner B. Design fluency: The invention of nonsense drawings after focal cortical lesions. Neuropsychologia. 1977;15:653–74. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(77)90070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nag SA, Rao SL. Remediation of attention deficits in Head Injury. Neurol India. 1999;47:32–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benton AL, Hamsher KS. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. New York: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao SL. Neuropsychological sequelae after head injury and its treatment. Q J Surg Sci. 1998;34:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ajayan P. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation in Head Injured Children. Bangalore: NIMHANS; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feuerstein R, Hoffman M. Instrumental Enrichment Teacher's Manuals: Jerusalem ICELP Press and Skylight. 1995 [Google Scholar]