Abstract

Background:

Mentally retarded and chronic mentally ill are being certified using IQ Assessment and Indian Disability Evaluation and Assessment Scale (IDEAS). They have been granted various benefits including monthly pension, from Ministry of Social Welfare, Government of India. The monthly pension appears to be the strongest reason for seeking certification and applying for government benefits. The caregivers appear to have only partial information and awareness about the remaining schemes.

Objective:

The study aims to assess the severity of disability in the mentally retarded and mentally ill who are certified for disability benefits, as well as to assess the trends of utilization of disability benefits over a 3 year period.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective, file review based study of certificates of patients certified for mental disability in the period of January 2006 to December 2008. Certificates of a total of 1794 mentally retarded and 285 mentally ill were reviewed. The data regarding utilization of disability benefits was assessed.

Results:

Patients from rural areas did not avail any benefits other than the disability pension. Among Mentally Ill, Schizophrenia accounted for highest certifications. Males had higher disability compared to females, and Dementia showed highest disability as per IDEAS.

Conclusion:

Though initial hurdles due to disability measurement have been crossed, disability benefits are still elusive to the vast majority of the disabled. Proper awareness and education will help in reducing the stigma and in the effective utilization of benefits.

Keywords: Chronic mentally ill, disability benefits, psychiatric disability, IDEAS scale

INTRODUCTION

In India, majority of the 125 million mental ill require intensive rehabilitation services.[1,2] The transient nature of the disabilities of mental illnesses and the nature of the socio-occupational impairment posed a challenge for the measurement of the disability. As this was the major hurdle in including mental illnesses into the government's social welfare benefits under the Persons with Disability Act of 1995,[3] the Rehabilitation Committee of the Indian Psychiatric Society developed the Indian disability evaluation and assessment scale (IDEAS),[2] which is now recommended by the Government of India to measure psychiatric disability.[4]

The disabled are eligible for the following welfare schemes from the government:[5–9]

Disability pension/unemployment pension

Disabled person's scholarship

Insurance scheme for the mentally challenged

Adhara scheme helping to set up small shops

Telephone booth

Free education up to 18 years

Free legal aid

Aids and appliances (for multiple disabilities)

3% Job reservation (only cerebral palsy included)

Concessional bus passes

Railway concession

According to Census 2001,[11] there are 2.19 crore people with disabilities in India, who constitute 2.13% of the total population. Of these, 9,40,643 are in Karnataka state, with 92,631 being mentally disabled. 75% of all persons with disabilities live in rural areas, 49% are literates and only 34% are employed.

Chaudhury et al.[12] found more people with schizophrenia in the rural areas and with dementia in the urban areas, with mood and anxiety disorders approximately evenly distributed. They also found that 64% of patients with schizophrenia, around 30% with mood disorders, 16.7% of anxiety disorders, had a disability of more than 40% on the IDEAS scale.

Jahan and Singh[13] found that only 6% of the guardians of mentally retarded were aware of the persons with disabilities (PWD) Act. Singh and Nizamie[14] reported poor awareness and underutilization of disability benefits.

Hence, in practice, disability benefits are still elusive for persons with mental disorders.

Aims of the present study

To assess the severity of disability in the mentally retarded and mentally ill certified for disability benefits.

To assess the trends of utilization of government benefits among chronic mentally ill, over a 3-year period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective, file review based study. The disability certificates of all patients approaching either Government Wenlock District Hospital or any psychiatric disability assessment camp in the district of Mangalore during the period of January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2008 (total of 3 years) were included in the review.

The study was done at Government Wenlock District hospital, Mangalore, Karnataka.

All disability assessments and certification for the entire district of Mangalore are done at Wenlock District Hospital. As per the standard procedure, the government psychiatrist, who is a member of the Psychiatric Disability Certification Board, assesses the disability percentage in mentally retarded from the tabular column of the IDEAS schedule, when matched with IQ score. The disability in mentally ill is assessed using IDEAS scale as per the standard procedure.[10] After the government psychiatrist signs the disability certificates, they are then countersigned by other members, including the district surgeon. Even in the Disability Camps conducted by Social Welfare Department, Government of Karnataka, as well as by NGOs and self-help groups, the details of the certificates issued are entered in the Disability Register maintained at Wenlock District Hospital. Hence, all data from psychiatric disability assessments, whether at the OPD of Wenlock District Hospital or at disability assessment camps, were entered in the Disability Register. Though it was not mandatory, the Department of Psychiatry at Wenlock District Hospital had made a note of the different concession forms signed in the Disability Register. Income tax benefits, railway concession, and free bus pass involved different sets of forms, and all these data were entered in the Disability Register. These data were very useful in evaluating the different benefits/schemes the disabled were applying for. This gives a very inclusive sample, with least amount of selection bias.

The details collected included name, out-patient number, age, sex, psychiatric diagnosis, IQ/IDEAS global score, disability percentages and data regarding the utilization of benefits other than the disability pension.

The data were analyzed by Chi-square test, Student's unpaired “t” test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Pearson's coefficient of correlation, using SPSS version 16.0.[15]

RESULTS

Mental retardation

Out of a total 1794 who were assessed and certified during the 3-year period, 421 were seen in 2006, 931 in 2007 and 442 in 2008. A total of nine disability assessment camps, organized by the Department of Social Welfare, NGOs and self-help groups, were organized in 2007, while in 2008 there were four camps. 2006 did not have any peripheral disability assessment camps.

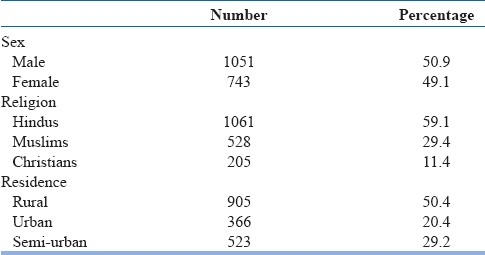

The socio-demographic profile [Table 1] revealed that the majority of the mentally retarded study population were males, Hindus, and from rural areas.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of certified mentally retarded

69 (3.8%) had borderline intelligence, 431 (24.1%) had mild MR, 579 (32.3%) had moderate MR, 523 (29.2%) had severe MR, and 191 (10.6%) were certified as having profound MR.

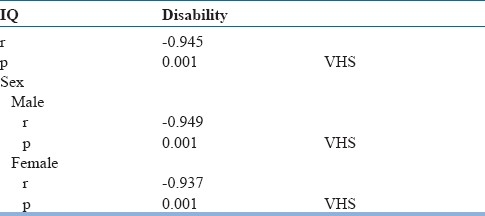

The IQ/SQ correlated negatively with the disability percentages for both males and females and this correlation was statistically very highly significant with r=–0.945 and P <0.001 [Table 2].

Table 2.

IQ correlation with disability

Across the years, the majority of certifications were in the moderate–severe retardation categories. Severe and profound retardation also showed a significant trend toward male sex. The disability percentage did not show any correlation with the utilization of benefits other than disability pension, while the place of residence showed a very high correlation. 99% of patients from rural areas did not avail any benefits other than the disability pension, which was very highly statistically significant with P <0.001. 6.6% of urban mentally retarded were availing special school education, while 6.8% were confined to rehabilitation/custodial care centers. 4.6% of the urban disabled availed income tax benefits.

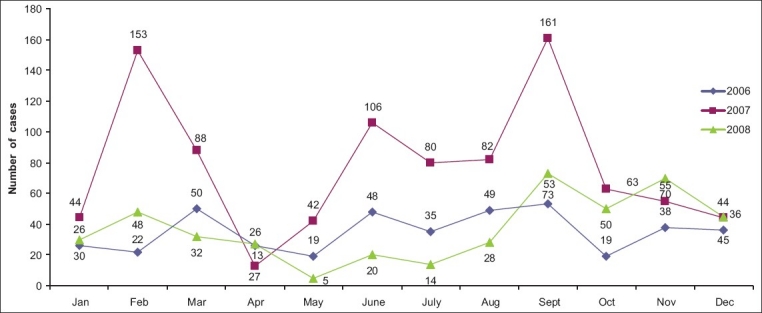

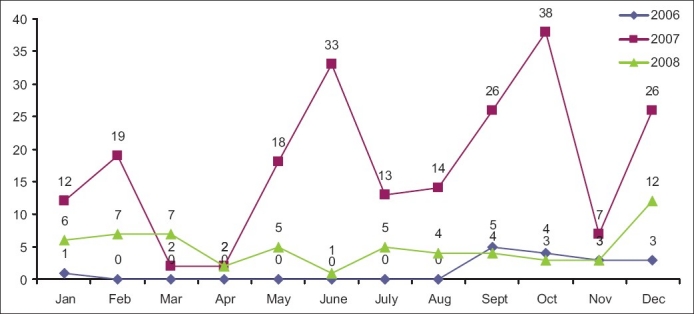

Of interest is the graph for 2007 showing a very high number of mentally retarded disability certifications, which was also statistically very highly significant (P<0.001) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The general trend in the number of cases of mentally retarded disability certifications across the 3 years

Mental illnesses

Of the 285 mentally ill who were certified as disabled in the 3-year period, 16 mentally ill were certified in 2006, 210 in 2007, and 59 in 2008.

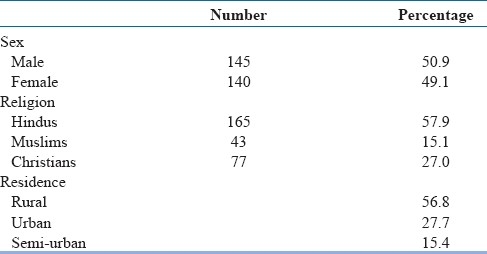

The socio-demographic profile [Table 3] shows that the majority of the mentally ill study population were males, Hindus, and from rural areas.

Table 3.

Socio-demographic profile of certified mentally ill

Of the clinical diagnoses, schizophrenia accounted for 65.3% and bipolar affective disorder accounted for 12.6%. 11.6% of cases were classified as chronic psychosis, of which many might be reclassified as having schizophrenia, according to recent ICD-10 criteria.[16] The disability was evenly distributed across different age groups, with no statistical difference obtained when either IDEAS global score or disability percentage was compared to age groups. Males had higher disability compared to females, which was statistically very highly significant with P<0.001 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

General trend of mental illness disability certifications across the 3 years

When the disabilities due to different clinical diagnoses were compared as per the IDEAS global scores, dementia showed the highest disability with a mean IDEAS global score of 16.67±1.15, which was statistically very highly significant with P<0.001.

99.4% of the disabled in rural areas had not availed any benefits other than disability pension, which was statistically very highly significant (χ2 =151.73; P<0.001). 62% of urban disabled were already residing in rehabilitation centers/custodial care centers. 47.6% of persons with a disability of more than 70% were not availing any benefits other than the disability pension, which is statistically very highly significant with χ2 =16.311 and P<0.001.

Again, the graph for 2007 shows a statistically very highly significant increase in the number of certificates (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Tracking the trends of utilization of the social welfare schemes for the mentally disabled gives the anchor points based on which we can replot our planning and resources for more effective utilization of the benefits by the target population. In this regard, the present study has brought into light several points which require attention and more research.

The statistically highly significant increase in the number of disability certifications in 2007 was probably due to the nine disability assessment camps organized. The increase in number corresponds to the camp dates during August–November. The dip in the number of certificates corresponds to the annual vacation during April. This understanding has implications toward planning of such camps and suggests a need for ongoing camps/referrals, rather than just being concentrated in certain months or in a certain year.

Earlier, disability among mentally retarded was calculated as the difference between 100 and IQ. However, the IDEAS schedule gives a much clearer method involving reading off from a tabular column. The current study shows that the IQ correlates negatively and in a very highly significant way with the disability percentage. This indicates the validity of the current disability percentage method as per IDEAS.

6.8% of the urban retarded, being confined to rehabilitation/custodial care centers, might be confounded by the fact that most of these centers are located in the city limits.

In the current study, among mental illnesses, schizophrenia accounted for majority of disability certifications and dementia was found to be the most disabling. However, the small sample size for dementia indicates the need for further research to be undertaken with a larger sample size.

Large numbers of the mentally disabled, especially from the rural areas, have not approached for any government benefits other than the disability pension. Earlier studies[13,14] have indicated the difficulty in getting disability certificates and also mentioned the poor awareness about the PWD Act. The current study also confirms poor awareness about the disability benefits and underlines the need for such awareness at all levels, from school teachers to parents/custodians of the disabled, to the organizers of Disability Camps. An exclusive education and awareness counter at Disability Camps would aid in spreading awareness in the peripheral outreach areas. This can be used in conjunction with other awareness programs like street plays, educating teachers, mass media, etc.

The authors also propose a single-window policy of benefits under the Department of Disabled Welfare/Ministry of Social Welfare, rather than making parents and guardians run around from railway stations to zilla panchayat offices for getting all the benefits. This would greatly reduce the caregiver burden, increase the approachability and also improve the utilization of government benefits.

This was a unique study conducted to assess the trends of utilization of government benefits among the chronic mentally ill. We have reviewed the trend of disability certifications over a long period of 3 years. This has included a large sample of 1794 mentally retarded and 285 mentally ill.

While the strong points of the government's disability assessment system have been discussed in this report, it has also highlighted the poor utilization of benefits other than the disability pension. The Indian Psychiatric Society has done laudable work in simplifying the disability assessment system. It has created an objective assessment method in an area of subjective disability.

The relevant government agencies which had earlier shown hesitation must now take notice and ensure that the disabled get their due benefits.

There were a few limitations of this study. This was a retrospective, file review based study. As the actual certifications are done during busy “Certification day Out Patient Days” and Disability Camps, more data regarding family history and comorbidity were missing and hence could not be used. A prospective study which also takes into consideration caregiver burden, awareness and satisfaction about the disability benefits from the government might be highly useful.

CONCLUSION

Mental disorders lead to significant socio-occupational dysfunction. Though initial hurdles due to disability measurement have been crossed, disability benefits are still elusive to the vast majority of the disabled. Proper awareness and education will go a long way in reducing the stigma and help in the effective utilization of benefits. Assessing the utilization of benefits assumes importance in this direction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to Mr. Shashidhar Kotian for his invaluable help with the statistical work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Turning Point. Mental Health and rehabilitation- Indian Context. [Last accessed on 2009 May 28]. Available from http://www.TurningPoint.org .

- 2.Thara R. Measurement of psychiatric disability. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:723–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amendments to PWD Act for Mentally Ill. [Last accessed on 2009 May 28]. Available from: www.acmiindia.org .

- 4.IDEAS (Indian Disability Evaluation and Assessment Scale) - A scale for measuring and quantifying disability in mental disorders. India: Indian Psychiatric Society; 2002. The Rehabilitation Committee of the Indian Psychiatric Society. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of Karnataka. Karnataka State Mental Health Rules 2007. [Last accessed on 2010 Nov 26]. Available from: karhfw.gov.in/Karnataka_state_mental_health_authority.pdf .

- 6.Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. National Policy for Persons with Disabilities, No.3-1/1993-DD.III. [Last accessed on 2010 Nov 26]. Available from: socialjustice.nic.in/nppde.php?pageid=3 .

- 7.Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (Disabilities Division), Government of India. Incentives to employers in the private sector for providing employment to the persons with disabilities. No. 2-4/2007-DDIII (Vol. II) [Last accessed on 2010 Nov 26]. Available from: www.nhfdc.org/incentdd.pdf .

- 8.Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. Acts/Rules and Regulations/Policies/Guidelines/Codes/Circulars/Notifications (Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities) [Last accessed on 2009 Jun 1]. Available from: http://socialjustice.nic.in/policiesacts3.html .

- 9.Directorate of Welfare of Disabled and Senior Citizens, Government of Karnataka. State Government Schemes. [Last accessed on 2008 Dec 20]. Available from: http://welfareofdisabled.kar.nic.in/schemes_stgov.html .

- 10.Guidelines for evaluation and assessment of mental illness and procedure for certification. Ministry of social justice and empowerment, Government of India. 2002. Feb 27th, [Last accessed on 2008 May 20]. Updated. Available from: http://social justice.nnic.in/disabled/mentguide.htm .

- 11.Census of India 2001-Data on Disability: Office of the Registrar General of India. [Last accessed on 2008 Jun 23]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/disability .

- 12.Chaudhury PK, Deka K, Chetia D. Disability associated with mental disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:95–101. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Nizamie SH. Disability: the concept and related Indian legislations. Mental Health Reviews. 2004. Accessed from http://www.psyplexus.com/mhr/disability_india.html. on Jan 1, 2009 .

- 14.Singh A, Nizamine SH. Disability: the concept and related Indian legislations. Mental Health Reviews. 2004. [Last accessed on 2009 Jun 5]. Available from: http://www.psyplexus.com/mhr/disability_india.html .

- 15.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Geneva: WHO; 1992. World Health Organization. SPSS Inc; SPSS 16.0 for windows.2008, SPSS Inc Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Geneva: WHO; 1992. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]