Abstract

Objective:

The aims of this study were (a) to describe the sociodemographic and clinical profile of women with unplanned pregnancies and consequent exposure to psychotropic drugs, (b) to describe the nature and timing of psychotropic exposure during pregnancy among these women, and (c) to examine the outcome of decisions related to pregnancy following consultation at a perinatal psychiatric service.

Materials and Methods:

Women attending the perinatal psychiatry services referred for accidental exposure to psychotropics were assessed by structured interviews for the following details: sociodemographic details, clinical details, psychotropic drug use, advice given in the clinic, and outcome related to this advice.

Results:

Fifty-three women were referred for counseling related to unplanned pregnancies and consequential psychotropic exposure. Forty-two women (79%) sought consultation in the first trimester. More than a third of the women, 19 (36%), were taking more than one psychotropic medication during the first consultation. Only 11 (20%) women had received any form of prepregnancy counseling prior to becoming pregnant. Of the 37 women who came for follow-up in the clinic, 35 (94%) of them continued the pregnancy.

Conclusions:

Unplanned pregnancies in women with mental illness are common and result in exposure to multiple psychotropic medications during the first trimester. Majority of women did not report of having prepregnancy counseling and which needs to be an integral part of treatment and education.

Keywords: Mental illness, pregnancy, psychotropics polytherapy

INTRODUCTION

Majority of mental illnesses affect women in their reproductive period. Following the advent of newer psychotropics with relatively minimal effects on fertility, more women are conceiving and are also planning for pregnancy.[1,2]

However, a large number of these pregnancies continue to be unplanned.[3,4] Hence, the chance of fetal exposure to psychotropic drugs, especially in the first trimester is high. With current pharmacological treatment being mostly symptom based, polytherapy is a rule rather than an exception.[5,6] This in turn increases the chance of women with unplanned pregnancies being on multiple drugs. There is ample evidence of an increase in teratogenicity with polypharmacy.[7–13] There is also emerging literature regarding involvement of transporter proteins that influence the extent of placental transfer of drugs and are also involved in the protective barrier function of the placenta. This fetal-placental circulation is established by 21 days’ gestation, which is fully formed by the end of the fourth month of gestation.[14] Moreover, safety of all psychotropic drugs in pregnancy has not been established and some drugs have documented evidence of teratogenicity.[15–17]

Four kinds of problems have been documented with psychotropic use in pregnancy. These include teratogenicity (which has received the maximum attention), labour-related problems, perinatal complications, and more recently metabolic disorders among mothers.[15,16,18,19,20] On the other hand, pregnancy is no more considered as protective against mental illness and evidence of untoward effects of pregnancy towards the health of both mother and fetus has been reported specially if drugs are discontinued.[21,22] Fear of teratogenicity may lead some mothers to discontinue medications abruptly, hence increasing the risk of relapse of the illness during pregnancy, which in turn may put both the mother and fetus at risk.[21,23] Thus, treating or preventing relapse of mental illness during pregnancy and puerperium is a clinical and ethical duty, in addition to avoiding or minimizing fetal or neonatal drug exposure.[24]

While studies have focused on specific complications related to the various psychotropics and on the effect of altering treatment, there is not much data on particulars such as the clinical profile of psychiatrically ill women who have unplanned pregnancies, the nature of psychotropic drugs that they are exposed to and decision-making following counselling about psychotropic exposure. Specialized perinatal services for mentally ill women are available in very few centers and are sparse in the developing world.[25,26] Women with severe mental illness are often not provided any information regarding effects of psychotropic medication on pregnancy apart from major teratogenicity and most women end up having unplanned pregnancies and minimal prepregnancy counseling.[27]

If this is true in the developed world, factors such as low education, inadequate psychiatric services, and poor control over contraception among women with severe mental illness in the developing world may lead to even higher number of unplanned pregnancies. Unfortunately, there is not much data related to the extent of this problem or to factors that are associated with unplanned pregnancies.

This study was conducted to assess the profile of women who were referred for accidental exposure to medications during pregnancy at a specialized perinatal psychiatry service in India. The aims of the study were threefold: firstly, we wanted to describe the sociodemographic and clinical profile of women with unplanned pregnancies and exposure to psychotropic drugs as a consequence. Secondly, it was our aim to describe the nature and timing of psychotropic exposure during pregnancy among these women, and finally, we wanted to examine the outcome of decisions related to pregnancy following consultation at the perinatal psychiatric unit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study sample was chosen from the perinatal psychiatry clinic, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India. The Hospital is a tertiary care psychiatry center that caters to mental health needs of the population in and around Bangalore city in South India and also handles referrals from other parts of India. The outpatient perinatal psychiatry service which is the first of its kind in South Asia, was started to provide specialized services for mentally ill women with perinatal psychiatric issues. These are in the form of pre-pregnancy counseling, planning pregnancy, handling accidental exposure to psychotropics in pregnancy and to mothers with post partum psychiatric illnesses and their infants. Pre-pregnancy counseling is an approach, which helps women with mental illness to take informed decisions regarding conception by weighing the risks and benefits of psychotropic medication. This service was initiated in the year 2006 and women either walk in directly or are referred from adult psychiatry consultants and local obstetricians.

On the whole, 180 women with different pregnancy-related issues were registered in the perinatal psychiatry clinic over two years. Of the 180 women, 53 were referred for counseling related to unplanned pregnancies and consequential psychotropic exposure. Data was collected on all the above parameters after obtaining informed consent.

Using a structured interview, data was collected from multiple sources including the women themselves, clinical records and a significant relative (usually spouse or primary care taker), on the following - sociodemographic details, clinical details, psychotropic drug use, advice given in the clinic, and outcome of this advice. Sociodemographic details included age, marital status, religion, socioeconomic status, background, and years of marriage. Clinical details included - psychiatric diagnosis, duration of the current episode, and current mental status assessed clinically. Psychotropic drug use included details regarding the nature and dose of psychotropics and the timing and of exposure with respect to pregnancy. Information on folate supplementation was also collected. The number of follow-ups, nature of advice provided, and obstetric liaison services provided were documented. Patients were advised for regular antenatal checkups and with ultrasound scanning of fetus for anomalies between 18–20 weeks. Clinical diagnosis was made by two consultant psychiatrists using the International Classification of Diseases 10.[28] Pregnancy outcome included details regarding continuation of pregnancy, nature of delivery, birth weight, any neonatal problems, and congenital anomalies. This data was collected by authors as part of routine clinical care in the service.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 11. The analyses were aimed at describing the basic sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of the sample using frequency statistics and measures of central tendency.

RESULTS

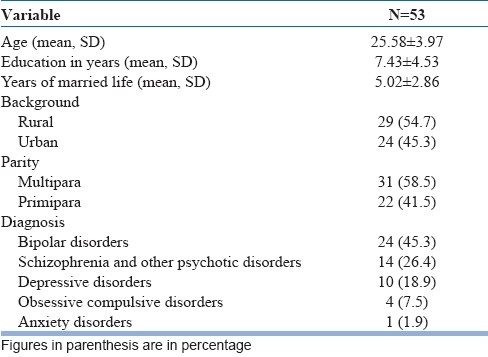

Women presented in the second decade with a mean age of 25.58 years (SD = 3.97) and were from both urban 24 (45%) and rural 29 (55%) backgrounds. More than half (n=28 ,53%) had received a high school education and all women were married. A total of 22 women (41.5%) were primiparous. The demographic details and the diagnoses are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio demographic and clinical profile

Clinical details - 38 (72%) of the 53 women were diagnosed to have a severe mental illness. Twenty-four women (45%) had bipolar affective disorder (mania or mixed affective type), 14 (26.4%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, 10 women had depression (19%) and the rest 5 (9%) women had anxiety disorders. Thirty-one (59%) women were symptomatic during the first consultation in the perinatal clinic based on clinical assessment. Past history of psychiatric illness during pregnancy, postpartum period was present in 16 (30%) women, and 27 (51%) women had at least one previous hospitalization for mental illness. Family history of postpartum illness was documented in one woman. History of past medical termination of pregnancy due to psychotropic exposure was found in 6 (11%) women.

Nature and timing of exposure to psychotropic medication

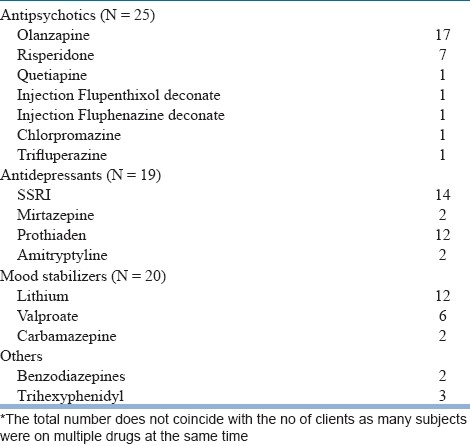

Forty-two (79%) of the 53 women sought consultation in the first trimester. Nineteen (45%) of the 42 women sought consultation within 4–8 weeks of conception and the rest 23 (55%) women in the 8–12 weeks of pregnancy. Eleven (21%) women sought consultation in the second trimester. More than a third of these women (n=19, 36%), were taking more than one psychotropic medication during the first consultation, while four women (7.5%) were taking three drugs at the first contact. Based on data in the records and self report, only 11 (20%) women had received any form of prepregnancy counseling, which included taking informed decisions regarding conception, by weighing the risks and benefits of psychotropic exposure to the fetus. 42 women did not report receiving any information about the need to plan pregnancies or the impact of psychotropics on maternal or fetal health. Details of drugs used during the first contact have been given in Table 2. Among 25 women who were on antipsychotics, Olanzapine was most commonly used (17/25) (57%) and among 20 women who were on mood stabilizers lithium was most commonly used (12/20) (66.7%). In this sample, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (73.7%) was the commonly used antidepressants. None of the women were on folate supplementation during conception or first trimester.

Table 2.

Psychotropic medication during the first consultation

Outcome of pregnancy

Sixteen (30%) women dropped out after the first consultation. However, of those who kept contact with the clinic (37/53), two women underwent a medical termination of pregnancy and the rest 35 women decided to continue pregnancy. Five women were lost to follow up during subsequent consultations. Pregnancy outcome details were available in 30 of the 53 women (56%). Nineteen women had vaginal delivery, among them 2 had vaginal delivery with forceps and 11 had caesarean sections. Apgar scores were available in 6 women, all of which were within normal ranges and details regarding the perinatal syndrome were not available. Congenital anomalies were not reported in any of the above live births.

DISCUSSION

The above study gives a glimpse of the profile of women with mental illness who have unplanned pregnancies. Several important findings emerge from this study, which has relevance for clinical practice. Firstly, almost one-third of the women (36%) were on multiple drugs and several of these drugs were there with established risk of teratogenicity (lithium, valproate, carbamazepine). Secondly, 51% of these women had a history of past psychiatric hospitalization and almost all were under the care of a psychiatrist. Despite this, evidence of formal pre-pregnancy education and counselling was available only in 13 (20%). Even these 13 women had unplanned pregnancy and exposure to psychotropics in spite of pre-pregnancy education. Thirdly, polypharmacy, particularly a combination of mood stabilizers with antidepressants/antipsychotics was seen in 13 women (24.5%), which needs to viewed seriously in light of emerging evidence of increased risk to the fetus with polypharmacy.[13] Fourthly, only 34% women had sought consultation in the first 4–8 weeks of pregnancy and all others delayed it to the later part of the first trimester or to the second trimester. This delay in consultation, once the maximum risk period for teratogenicity is over, often leads to dilemmas in decision making about continuation or termination of pregnancy. It also hampers the opportunity to rationalize treatment using least number of drugs with minimal effective dosage during the first trimester of pregnancy. The fact that majority of the (95%) women who were followed up had decided to continue their pregnancy also has important implications for clinical practice and stresses on the need for preventive measures in minimizing fetal exposure of psychotropics.

Among the psychotropics, the most commonly used drug was olanzapine, 17 (57%). While there has been no major teratogenic risk reported with olanzapine, concerns have been raised in the recent literature regarding its role in gestational diabetes among pregnant women and large for gestational age babies (LGA).[19,20,29,30] The risk for gestational diabetes may be more among women with obesity or a family history of diabetes. Women in our study were largely unaware of these risks and had not been told about them.

None of the women in the above study were prescribed folate supplementations despite being on valproate and carbamazepine. Folate supplementation is considered essential for women who are on psychotropics and are at risk for pregnancy mainly during conception and first trimester.[31]

The findings from this study have important implications for clinical practice. All women undergoing treatment for mental illness who are in the reproductive age group must be counseled about the impact of psychotropics on pregnancy and the fetus. In addition, education regarding planning of pregnancy in order to decrease the number of medications and use of the lowest effective dose of drug must be stressed. Most women at the time of consulting us were clinically symptomatic, it is hence important to involve the partner or spouse and a family member in this discussion. It is possible, that when symptomatic, women are careless about contraception and/or pregnancy goes undetected in the early stages. Finally, women need to be told to report as early as possible if they even suspect pregnancy in order to minimize risks and plan a safe pregnancy. Reproductive issues such as contraception and pregnancy, need to be part of routine clinical assessment and information on each follow-up.

Women in our study were from both urban and rural areas of South India, however, their educational levels were low. It is possible that women with a better educational background make more informed choices about pregnancy when on psychotropics. Also, women in India often do not have control over contraception issues and are expected to have children soon after marriage regardless of mental illness or treatment. This often precludes chances of discussion regarding a planned pregnancy. However, given our findings of polypharmacy and most women contacting the psychiatrist late in the first trimester, active efforts in this direction may still be worthwhile. Culturally suitable models of pre pregnancy counseling and planning are needed for women with severe mental illness given the important implications. So while our findings may not be generalisable to all settings and cultures, it has important implications for women in most underprivileged and developing country settings.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Gregoire A, Pearson S. Risk of pregnancy when changing to atypical antipsychotics. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:83–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickson RA, Edwards A. Clozapine and fertility. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:582–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.582b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller LJ, Finnerty M. Sexuality, pregnancy and childrearing among women with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:502–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.5.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coverdale JH, Turbott SH, Roberts H. Family planning needs and STD risk behaviours of female psychiatric outpatients. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:69–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman LS. Comorbid medical illness in psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2:256–63. doi: 10.1007/s11920-996-0019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George TP, Krystal JH. Comorbidity of psychiatric and sub-stance abuse disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2000;13:327–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headley J, Northstone K, Simmons H, Golding J. ALSPAC Study Team. Medication use during pregnancy: Data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of parents and children. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:355–61. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malm H, Martikainen J, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ. Finnish Register-Based Study. Prescription drugs during pregnancy and lactation—a Finnish register-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;50:127–33. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malm H, Martikainen J, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ. Prescription of hazardous drugs during pregnancy. Drug Saf. 2004;27:899–908. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olesen C, Steffensen FH, Nielsen GL, Berg L de Jong-van den, Olsen J, Sørensen HT. Drug use in first pregnancy and lactation: A population-based survey among Danish women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;55:139–44. doi: 10.1007/s002280050608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donati S, Baglio G, Spinelli A, Grandolfo ME. Drug use in pregnancy among Italian women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;56:323–8. doi: 10.1007/s002280000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacroix I, Damase-Michel C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Prescription of drugs during pregnancy in France. Lancet. 2000;356:1735–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peindl KS, Masand P, Mannelli P, Narasimhan M, Patkar A. Polypharmacy in pregnant women with major psychiatric illness: A pilot study. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:385–92. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000300124.83945.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JS, Newport DJ, Stowe ZN, Donovan JL, Pennell PB, DeVane CL. The emerging importance of transporter proteins in the psychopharmacological treatment of the pregnant patient. Drug Metab Rev. 2007;39:723–46. doi: 10.1080/03602530701690390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: Dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:592–606. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen LS, Rosenbaum JF. Psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: Weighing the risks. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton SW, Misri S, Corral MR, Perry KF, Kuan AJ. Antipsychotic medication during pregnancy and lactation in women with schizophrenia: Evaluating the risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:959–65. doi: 10.1177/070674370204701008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viguera AC, Cohen LS, Baldessarini RJ, Nonacs R. Managing bipolar disorders during pregnancy: Weighing the risks and benefits. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:426–36. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichman CL. Atypical antipsychotic use in pregnancy: A retrospective review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:53–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis M, Kallini B. Maternal use of antipsychotics in early pregnancy and birth outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:279–88. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318172b8d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viguera AC, Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Risk of occurrence of bipolar disorder in pregnant and non pregnant women after discontinuation of lithium maintenance. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;1157:1509–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blehar MC, Depaulo JR, Gershon ES, Reich T, Simpson SG, Nurnberger JI., Jr Women with Bipolar disorder: Findings form the NIMH genetics initiative sample. Psychopharmacol bull. 1998;34:239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen LS, Atshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or dis-continue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295:499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai G, Chandra PS. Ethical challenges in managing pregnant women with mental illness. Indian J Med Ethics. 2009;2:75–7. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2009.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wan MW, Moulton S, Abel KM. The service needs of mothers with schizophrenia: a qualitative study of perinatal psychiatric and antenatal workers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulkarni J, McCauley-Elsom K, Marston N, Gilbert H, Gurvich C, de Castella A, et al. Preliminary findings from the National Register of Antipsychotic Medication in Pregnancy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:38–44. doi: 10.1080/00048670701732723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magalhães PV, Kapczinski F, Kauer-Sant’anna M. Use of contraceptive methods among women treated for bipolar disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:183–5. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0060-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Classification of Disease. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newham JJ, Thomas SH, MacRitchie K, McElhatton PR, McAllister-Williams RH. Birth weight of infants after exposure of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Prospective comparison study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:333–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermuri MP, Rasgon NL. A case of olanzapine-induced gestational diabetes mellitus in the absence of weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1989. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1222e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stowe Z, Leibenluft E, Cohen L, Miller L, et al. Management of bipolar disorder during pregnancy and the post partum period. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:608–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]