Abstract

In view of appreciable improvements in health care services in India, the longevity and life expectancy have almost doubled. As a result, there is significant demographic transition, and the population of older adults in the country is growing rapidly. Epidemiological surveys have revealed enormous mental health morbidity in older adults (aged 60 years and above) and have necessitated immediate need for the development of mental health services in India. The present population of older adults was used to calculate psychiatric morbidity based on the reported epidemiological data. The demographic and social changes, health care planning, available mental health care services and morbidity data were critically examined and analyzed. The service gap was calculated on the basis of available norms for the country vis-à-vis average mental health morbidity. Data from a recent epidemiological study indicated an average of 20.5% mental health morbidity in older adults. Accordingly, it was found that, at present, 17.13 million older adults (total population, 83.58 millions) are suffering from mental health problems in India. A differing, but in many aspects similar, picture emerged with regard to human resource and infrastructural requirements based on the two norms for the country to meet the challenges posed by psychiatrically ill older adults. A running commentary has been provided based on the available evidences and strategic options have been outlined to meet the requirements and minimize the gap. There is an urgent need to develop the subject and geriatric mental health care services in India.

Keywords: Geriatric mental health, mental health morbidity, mental health needs, older adults

INTRODUCTION

Ever since independence, India is passing through a phase of rapid transition in almost all areas, be it social, demographic, health care or economic. The effects are reflected in social change, emerging nuclear family systems, increase in population due to improving health care services, economic growth reflected in industrialization, urbanization, infrastructural developments, etc. The 21st century India is quite different from the India around independence in late ‘40s and ‘50s. The transformed India has newer and newer challenges in almost all walks of life. A very rapidly emerging issue relates to developing services and care for the grey segment of the population whose numbers are growing every year.

THE GREYING INDIA: DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES

Aging of the population is one of the most significant components of demographic change besides other changes like rapid population movements, increase in life expectancy at birth, improving vital statistics, etc. A look at the vital statistics indicate that the infant mortality rate (under 1 year) reduced from 80/1000 in 1991 to 52/1000 in 2008; the crude death rate reduced from 160/1000 in 1970 to 80/1000 in 2008; the life expectancy increased from 49 years in the ‘70s to 64 years in 2008.[1] The net result is growth in the greying sector of the Indian population and the consequent change in the demographic pyramid.

The pace with which the population of older adults in India is growing (1951–5.3%, 1981–6%, 1991–6.8%, 2001–7.4%, 2006–7.5%; and projected for 2026–12.4%) is likely to become a challenge in the very near future.[2–4] The population projections and changing demographic scenario of India indicate that the growth of older Indian adults in absolute numbers is comparatively faster than that in the other regions of the World. The population of older adults aged 60 years and above increased from about 20 million in 1951[2] to 77 million in 2001[3] to 83.58 million in 2006, and is expected to increase to 173 million in 2026.[4] Thus, the number of older adults will approximately be doubled by the year 2026 (173 million) in comparison with the year 2006 (83.6 million) in India.

SOCIAL CHANGES

India traditionally lived in joint family set ups with agrarian economy where everyone shared responsibilities, financial gains, social obligations, etc. and elders got all the respect from junior members of the family. During the last 50 years, economic and technological changes have speeded up in such a way that the society as a whole was forced to change to suit rapid urbanization, industrialization and developments in information and communication technology. Rapid movements of population from ancestral dwellings to far away places in search of economic gains have led to disintegration in the joint family set ups. Further, national programs such as population control is further shrinking the size of the families. The number of children is getting lesser and lesser and they also move away for education and livelihood. As a result, nuclear families are emerging at a fast pace where older adults are being left in ancestral houses having little or no personal, personnel, emotional, economic, social support and care. Indian studies have reported that individuals of nuclear families are more susceptible to developing psychological problems than those of joint families[5–7] because of breakdown in the traditional support system.[8]

Further, the changing social scenario in the name of modernization is influencing the interpersonal relations in a negative manner. The members of traditional joint Indian families have been respecting and caring for their older adults dutifully. The modernization and emergence of nuclear families is gradually eroding these traditional living patterns to the extent that the Government of India had to incorporate an act for the care and protection of the older adults by their children – “The Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizen Act, 2007.” The demographic and social changes are adversely affecting the health and care of the older adults and development of health care services for them as well.

HEALTH CARE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENTS IN INDIA: THE ONGOING SCENARIO

The issue of providing physical and mental health care to older adults is deeply rooted in health care planning, development, management and various available health systems in India, such as Ayurvedic, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, Homeopath (AYUSH), etc. To look into the history of health planning and health care development in India, one will have to track down to the past.

India, one of the most ancient civilizations of the world, had concepts of environmental sanitation as evidenced in excavations of the Indus Valley (Mohenjodaro and Harppa), but any kind of health system was developed after the invasion in India by the Aryans around 1400 B.C., and probably during this period, Ayurveda and Siddha came into existence. These systems of health care remained embedded in Indian religious systems and educated unity of the physical, mental and spiritual aspects of life.[9] The concept of Bhavantu Sukhinh sarve Santu Niramaya (may all be free from disease and may all be healthy) was propounded by Indian sages. The Post-Vedic period (600 B.C.– 600 A.D.) was dominated by Buddhism and Jainism and, around the same period, medical education was introduced by the ancient universities of Taxila and Nalanda leading to the titles of Pranacharya and Pranavishara.[9] The hospital system was developed during the reign of Rahula Sankrityana (son of Buddha) for men, women and animals, which was further expanded by King Ashoka. The older adults were not categorized separately.

During the next reign (650–1250 AD), Muslim rulers around 1000 A.D. introduced the Arabic Medical system called Unani system in India. Following that, by the middle of the 18th century (1757), the British established their rule in India, which ended in 1947. The British system of medical care dominated the health care, and various public health plans and policies were developed and implemented during this period. However, even at that time there was no categorization for older adults separately for health care and thus the health care to older adults was provided considering them just extension of the adults.

The Government of India Act, 1935 amended 1919 Act granting more autonomy to the states, a Central Advisory Board of Health was set up in 1937 as a central committee to coordinate the public health activities in the country with the Public Health Commissioner as Secretary and members of various States as representatives. The Bhore committee was appointed in 1943 to survey the existing position of health condition and health organizations in the country as well as to make provisions for the future development. Principally, the Bhore Committee recommended integration of all kinds of health services through a public health system, consisting of sub-centers, primary health centers, rural hospitals, district hospitals, specialist hospitals and teaching hospitals. The allopathic system of health care has principally developed on these bases in the country and nearly similar emphasis is being laid down on indigenous systems of medicines such as AYUSH. Voluntary health agencies like NGOs, national and state health programs, unregistered medical practitioners and faith and folk healers provide additional health care support in the country. India is signatory to the Alma Ata declaration 1977 and thus was committed to provide health to all by the year 2000. In pursuit of this, health care for children and adolescents, adult women and men were categorized and developed but health care for older adults was not categorized and both physical and mental health care continued to be provided as for adults.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PROFILE OF MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS OF OLDER ADULTS

Till about a decade ago, older adults were considered to be an extension of adult population and, as a result, good epidemiological studies focusing on older adults alone were hardly carried out in India. Also, hardly ever did anyone think about developing health care services for this segment of the population. With the realization that they are distinct psychologically, biologically and socially, the approach to older adults is now changing in the country. Focused epidemiological studies are now being carried out and morbidity data is emerging. Reports of various epidemiological studies indicate a variable degree of mental health morbidity in older adults.[10–16] In Pondicherry (South India), psychiatric disorders among older adults were found to be 17.4%.[17] Another epidemiological study from Uttar Pradesh (North India) reported 43.3% of the elderly to be suffering from one or the other mental health problems as against 4.7% adults.[14]

Further, it has been reported that in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), e.g. India, cases of dementia will increase quickly,[18] and mental health conditions are an important cause of morbidity and premature mortality.[19] Higher mental health morbidity in the underprivileged class of the society is reported.[14]

The results of two of the largest epidemiological studies carried out in urban and rural Lucknow in North India with support from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) using a sound methodology revealed that 17.3% urban and 23.6% rural older adults aged 60 years and above suffer from syndromal mental health problems and 4.2 urban and 2.5% of rural older adults suffer from sub-syndromal mental health problems.[15–16]

Depression and dementia have been widely studied in older adults. The prevalence of dementia in India has been reported to be variable, from 1.4% to 9.1%.[14–16,20–24] In Indian studies, depression was thrice more common than mania, occurring for the first time after 60 years.[25] Depression was found to be a common diagnosis in the geriatric population.[15–16] The prevalence of major depression was reported to be around 60/1000 in the general population in an Indian Study.[26] The prevalence of neurotic depression in the rural elderly was found to be 13.5%. A recent report indicates that 5.8% of the urban and 7.2% of the rural older adults primarily suffer from mood (affective) disorders; 2.4% of the urban and 2.1% of the rural older adults are primarily suffering from neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and 0.6% of urban and rural older adults primarily suffer from psychotic disorders.

THE BURDEN OF MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN OLDER ADULTS

The burden of mental health problems has been calculated on the basis of a recent study carried out in the country.[15–16] The average prevalence of mental health problems both in rural and urban communities indicates that 20.5% of the older adults are suffering from one or the other problems.

[(Urban-17.3%+Rural-23.6%)/2=20.45%, i.e. 20.5%]

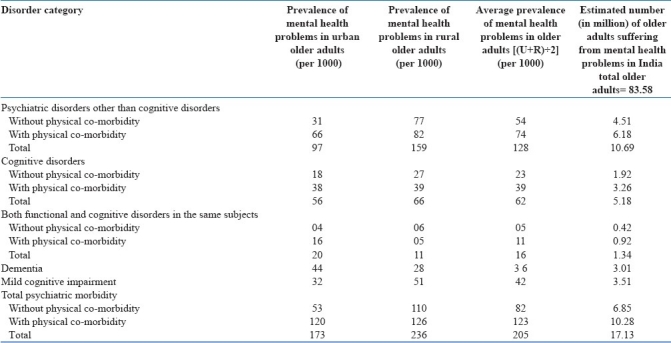

Translating this prevalence data over the current population of the older adults aged 60 years and above, which is 83.58 millions, figures out a terrifying picture of psychiatric disorders and burden of mental health problems in older adults of the country [Table 1].

Table 1.

Thus, 17.13 million older adults are suffering from one or the other diagnosable mental health problems in India. This in itself is testimony to the magnitude of the burden.

MENTAL HEALTH CARE FACILITIES FOR OLDER ADULTS IN INDIA

A search of the Indian literature on health care of older adults, particularly those suffering from mental health problems, opens up several articles.[27–31] However, these throw only scanty light on the development of geriatric care services in India. It is evident that the geriatric care is being provided by all kinds of health care agencies available in India without any specialization or focused approach. Most hospitals in the country do not have specialized geriatric care facilities. It is stated that lack of priority accorded to the healthcare needs of the elderly seem to perpetuate the low level of public awareness about mental health problems of old age.[32] Dementia and other mental disorders of older people remain hidden problems rarely brought to the attention of healthcare professionals and policy makers.

More than 70% of the older Indian adults live in rural areas,[30] and 52% of them do not have any income.[27] In rural areas, health and mental health care of older adults are met through quacks, faith and folk healers or the AYUSH practitioners as allopathic doctors and hospitals are available at a distance in urban areas and approaching urban hospitals is a real problem with older adults. Further, the health problems of older adults are not cared for as it is attributed just to ageing.

The mental health morbidity burden data and constitutional provisions to provide appropriate health care to all citizens in India necessitate development of not only geriatric physical health services but also geriatric mental health services if specialized services are to be provided. No formal survey has been carried out to indicate the percentage of psychiatrically ill older adults seeking various kinds of OPD/IPD allopathic or AYUSH treatment facilities and how many remain unattended or how many visit quacks, faith and folk healers? At present, all available health care facilities and service providers are stakeholders for health care of older adults. Specific and specialized services for older adults could not be developed as, until 1998, there was no government policy for older adults.

On an average, 10–15% of the hospital beds are occupied by the older adults.[27] The principles of health economics indicate that older adults require treatment for longer periods and are best kept at home for better resource utilization. But, the increase of female participation in the work force adversely affects the care of older adults at home. Insufficient place and lack of space in houses are rapidly eroding the rights of older adults.

Psychiatrically ill patients with physical comorbidity may find a place in a hospital but pure psychiatry patients are often refused hospitalization in general hospitals and may find place only in adult psychiatric hospitals where there is no specialization in terms of manpower, skills and infrastructure. This is the present state of affairs for mentally ill older adults in India. The research contributions of India in geriatric research are less than 1% in the world scientific literature. Extensive research on geriatric mental health using social, biochemical, genetics and molecular aspects is available from other parts of the world.[33] The Indian government is spending less than 0.1% of the GDP on geriatric health research and care, and this in itself is testimony to the fact that geriatric physical and mental health services are hardly available in the country. The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Govt. of India (2008), in its revised Integrated Programme for Older Persons has made provisions for mental health care and specialized care for the older persons to provide mental health care intervention programs to the elderly by offering financial supports to the organizations but, to the best of our knowledge, no center in the country has initiated any mental health activity under this provision. In the given situation, it appears futile to comment upon the available mental health care services for older adults in organized and non-organized sectors.

MENTAL HEALTH SERVICE REQUIREMENTS FOR OLDER ADULTS IN INDIA: “AN ESTIMATE”

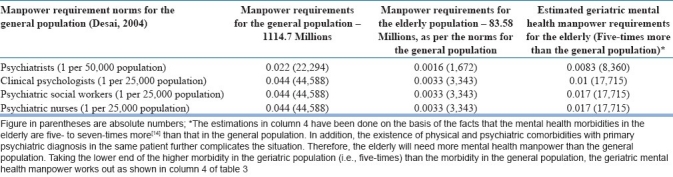

The manpower and physical infrastructure requirements to serve mentally ill older adults have been worked out on the basis of norms as provided in the Mental Health ACT, 1987, and relaxed and modified by the Gazette of India no. 252 [Table 2] and criteria of norms proposed by Desai et al. in terms of population [Table 3].[34–35] The country needs to arrange mental health care services for 17.13 million older adults in the immediate future. The estimate of manpower requirements have been worked out assuming that of the total mentally ill older adults, about 50% (8.56 million) might be seeking professional help and, of these, only 7–10% (0.59–0.86 million) will be in need of hospitalization (experience from a psychogeriatric hospital). In view of this, the requirements have been calculated taking an average of 8.5% (.72 million) of patients needing hospitalization as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Requirements (full figures) for geriatric mental health beds and manpower as per the Mental Health Act, 1987, norms

Table 3.

Manpower norms and requirements for the general population vis-a-vis for older adults and the proposed estimates

The manpower and other infrastructure requirements as estimated on the basis of both norms[34–35] [Tables 2 and 3] very clearly highlight the enormous need to meet the service challenges posed by the psychiatrically ill older adults in the country. The requirements based on both the estimations differ but are nearly similar in many respects. The assumptions that have been taken into account in calculating the requirements as per the Mental Health Act, 1987 norms, are based on the principles as laid down by Arie and Halpain[36–37] and on personal experience of the authors from a fully developed psychogeriatric hospital with both indoor and outdoor facilities.

Against these requirements, virtually speaking, there is hardly any infrastructure or manpower especially and specifically meant for Geriatric Mental Health. Therefore, one can only imagine and visualize the “gap” and the “requirements” for geriatric mental health services in India. The country will have to generate resources to minimize this vast gap if older adults are to be cared for and quality is to be added to their increasing quantity life.

The options

The present status of geriatric mental health care services has been enumerated in the preceding lines. The question is how to minimize the vast gap between geriatric mental health service requirements and available services? The following are the options:

Integration and training

This approach envisages deprofessionalization and decentralization of service and appears feasible on the face. Primary health care providers (medical and paramedical) will have to be trained in the skills of geriatric mental health care. In the shortest possible time, the cadre of primary health care providers will be available to make an early diagnosis and initiate treatment. At the same time, some minimum infrastructures (earmarking some of the existing beds) at least at district headquarter levels with provisions of medicines to treat and manage the older adults may be made available for geriatric mental health care. The additional requirements would be of psychogeriatric physicians, social workers, clinical psychologists and nurses to impart training.

This approach has promise to start services with minimum input and in minimum time. However, as per our experience, such strategies sound good on paper but fail in the field. The National Mental Health Program (NMHP) was started with similar objectives to deprofessionalize and decentralize general mental health care services to reach the unreached at peripheral levels in late ‘90s. Training manuals and training programs were developed and training of health providers was initiated with a very promising note. Within a decade, this method of implementation of NMHP was modified, perhaps because of its limited success. The NMHP is now being implemented as a District Mental Health Program (DMHP) in selected districts of each state of the country. A staff of a psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, social worker, nurse, office staff clerk, driver, nursing orderly and sweeper has been provided for each district under DMHP to provide mental health care. The program has provision of medicines as well. Although no formal evaluation has been done, the DMHP appears to be bearing fruits. Sooner or later, the approach of deprofessionalization and decentralization as proposed in this option may meet the same fate.

Integrating geriatric mental health in NMHP

The NMHP is now being implemented as DMHP. A short-term strategy could be to impart training in geriatric mental health to the general mental health specialists managing DMHP. From the allocated 10 beds for DMHP, few beds (20%) may be allocated to geriatric mental health, with provisions of medicines and thus the geriatric mental health services can be started with minimum inputs. The only requirement would be psychogeriatric trainers to train staff of the DMHP. This may be a viable proposition to start with. However, a good psychogeriatric service system would develop only when it will be manned by specially trained psychogeriatric medical and allied manpower. Rao and Shaji (2007) are of a similar opinion and propounded that specialized geriatric mental health services are possible only in general or teaching hospitals depending on the availability of trained manpower.

Manpower and infrastructure development

This is a sound approach. It is time taking and costly, but the outcome will be appreciable. A strategic planning needs to be done to materialize this approach. This approach would require development of teaching and training centers in the country in psychogeriatrics. A viable policy will have to be developed so that within the available resources, such teaching, training, clinical and research centers could be established. To start with, a minimum of one Department of Geriatric Mental Health in each state and union territory and units of Geriatric Mental Health in each medical college of the state/union territories can be established on the patterns of the state of Uttar Pradesh. Further, expansion of this strategy may be done depending on the size of the state and the available resources. Undoubtedly, it is a costly proposal but in the long term, as in case of NMHP, this will be the only viable option.

A national policy for geriatric mental health

Three options to develop psychogeriatric services have been proposed. Whatever option is undertaken, a policy at the highest level of healthcare will have to be formulated to formalize and implement. For services, policy and planning, sufficient research data is available from almost all corners of the country to formulate a viable policy to develop mental health care services for older adults. This should be immediately addressed to. It is also pertinent to mention here that as of date the geriatric mental health is not a recognized medical discipline in the country by the highest medical regulatory body, i.e. Medical Council of India (MCI). The subject should now be recognized as there is sufficient ground for recognizing geriatric mental health as a distinct medical subject as elsewhere in the world. Further, geriatric mental health education should be incorporated in undergraduate medical education as well. This will attract more and more people to join the subject and serve the mentally ill older adults. This will also help in allocating separate financial resources at the level of government.

CONCLUSIONS

It is to be emphasized that the subject of geriatric mental health/psychogeriatrics needs to be developed in India at the earliest in view of a spirally growing population of older adults and the high mental health morbidity in them. The options have been identified for this and initiatives should be undertaken to formulate a policy for developing services based on available research data, requirements, available infrastructure and gap. Equally important is to get the subject of geriatric mental health recognized to attract the medical and paramedical people to take up careers in the subject and to establish specialized psychogeriatric services in the country.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.UNICEF-India-Statistics.htm. [Last accessed on 2010 June 6]. available from: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/stats_popup10.html .

- 2.Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. India: Govt. of India; 1991. Aging in India. Occasional paper no. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banthia J K, editor. Reports and Tables on Age: Series-1 India. Census of India: Controller of Publications (Delhi), Govt. of India; 2001. Census. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of social Defense, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. India: 2008. NISD. Age care in India: National Initiative on care for elderly. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Kumar R. Three hundred urban families—a psychiatric study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1967;9:280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Mahendru RK, Kumari P. A psychiatric survey of 500 rural families. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:183. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sethi BB, Gupta SC, Mahendru RK, Kumari P. Mental health and urban life-study of 850 families. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124:243–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.124.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra HD. Family structure, dynamics and psychiatric disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:335–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao KN. The Nations Health, -6: Director, Publications Division (Delhi), Govt. of India. 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramchandran V, Menon M Sarda, Murthy B Ram. Psychiatric disorders in subjects aged over fifty. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;22:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao AV, Madhavan T. Gerospsychiatric morbidity survey in a semi-urban area near Madurai. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:258–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prakash R, Chaudary SK, Singh U. A study of morbidity pattern among geriatric population in the urban area of Udaipur, Rajastan. Indian J Community Med. 2004;119:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava RK, editor. Multi-centric study to establish epidemiological data on health problems in elderly. WHO-Govt. of India Report. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiwari SC. Geriatric psychiatric morbidity in rural northern India: Implications for the future. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:35–48. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari SC, Kar AM, Singh R, Kohli VK, Agarwal GG. An epidemiological study of prevalence of neuro-psychiatric disorders with special reference to cognitive disorders, amongst (urban) elderly- Lucknow study. New Delhi: ICMR Report; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiwari SC, Kar AM, Singh R, Kohli VK, Agarwal GG. An epidemiological study of prevalence of neuro-psychiatric disorders with special reference to cognitive disorders, amongst (urban) elderly- Lucknow study. New Delhi: ICMR Report; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Premarajan KC, Danabalan M, Chandrasekar R, Srinivasa DK. Prevalence of psychiatry morbidity in an urban community of Pondicherry. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:99–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prince M. The need for research on dementia in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:993–1000. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prince M, Livingston G, Katona C. Mental health care for the elderly in low-income countries: A health systems approach. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:5–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramachandran V, Menon MS, Ramamurthy B. Family structure and mental illness in old age. Indian J Psychiatry. 1981;23:21–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra V, Ganguli M, Pandav R, Johnston J, Belle S, DeKosky ST. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in rural India: the Indo-US study. Neurology. 1998;51:1000–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vas CJ, Rajkumar S, Tanyakitpisal R, Chandra V. Alzheimer's Disease: The brain killer. New Delhi: WHO; 2001. p. 50. (208). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaji KS, Kishore NR Arun, Lal K Praveen, Pinto C, Trivedi JK. Better mental health care for older people in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:367–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaji S, Promodu K, Abraham T, Roy KJ, Verghese A. An epidemiological study of dementia in a rural community in Kerala. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:745–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao AV. Psychiatric morbidity in the aged. Indian J Med Res. 1997;106:361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao AV, Madhavan T. Depression and suicide behaviour in the aged. Indian J Psychiatry. 1983;25:251–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnakumar A. The old and the ignored. Chennai: 21 Frontline-India's National magazine from the publishers of The Hindu; 2004. pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meisheri YV. Geriatric services-need of the hour. [Last accessed on 2010 May 25];J Postgrad Med (online) 1992 38:103. Available from: http://www.jpgmonline.com/text.asp?1992/38/3/103/703 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swami HM, Bhatia V. Primary geriatric care in India. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2003;34:147–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gargadharan KR. Global aging roundtable 2005 white house conference on aging. Remarks by K.R. Gangadharan, Heritage Hospital, Hyderabad, India. 2005 (cited on 2010 May 25) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingle GK, Nath A. Geriatric health in India: Concerns and solutions. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:214–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.43225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao TS, Shaji KS. Demographic aging: Implications for mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:78–80. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao TS, Praveena B, Rao J. Geriatric mental health: Recent trends in molecular neuroscience. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:3–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai NG, Tiwari SC, Nambi S, Shah B, Singh RA, Kumar D, et al. Urban mental health services in India: How complete or incomplete? Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:195–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Mental Health Act. Act no. 14 of 1987- together with Central Mental Health Authority Rules, 1990 and State Mental Health Rules, 1990 with short notes. Lucknow: EBC Publishing (P) Ltd; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arie T. Morale and planning of psychogeriatric services. Br Med J. 1971;3:166–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5767.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halpain MC, Harris MJ, McClure FS, Jeste DV. Training in geriatric mental health: Needs and strategies. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1205–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]