Abstract

Calcium is required for many cellular processes including muscle contraction, nerve pulse transmission, stimulus secretion coupling and bone formation. The principal source of new calcium to meet these essential functions is from the diet. Intestinal absorption of calcium occurs by an active transcellular path and by a non-saturable paracellular path. The major factor influencing intestinal calcium absorption is vitamin D and more specifically the hormonally active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3). This article emphasizes studies that have provided new insight related to the mechanisms involved in the intestinal actions of 1,25(OH)2D3. The following are discussed: recent studies, including those using knock out mice, that suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 mediated calcium absorption is more complex than the traditional transcellular model; evidence for 1,25(OH)2D3 mediated active transport of calcium by distal as well as proximal segments of the intestine; 1,25(OH)2D3 regulation of paracellular calcium transport and the role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in protection against mucosal injury.

Keywords: intestine; transport; calcium; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; transient receptor potential vanilloid type 6 (TRPV6); calbindin; plasma membrane calcium pump PMCA1b; claudin-2; claudin-12; cadherin-17

Introduction

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), the hormonally active form of vitamin D, is the most significant factor controlling intestinal calcium absorption [1, 2]. Two modes of intestinal calcium absorption have been proposed: one is a saturable, active, transcellular process and the other mode is non-saturable, paracellular, occurs at luminal concentrations of calcium > 2 – 6 mmol/l and is driven, at least in part, by the integrity of tight junctions [3, 4]. Calcium absorption occurs in each segment of the small intestine and is determined by the rate of absorption and the transit time through each segment. In mammals most of the ingested calcium is absorbed in the lower segments of the small intestine (mostly in the ileum) where the transit time is longer compared to more proximal segments. Only about 8 −10% of calcium absorption takes place in the mammalian duodenum although its capacity to absorb calcium is more rapid than any other segment [3 – 7]. As the body’s demand for calcium increases as a result of a diet deficient in calcium or due to growth, pregnancy or lactation, synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 is increased resulting in the stimulation of active calcium transport [1, 2]. Although the duodenum has been a focus of research related to 1,25(OH)2D3 mediated active calcium absorption, 1,25(OH)2D3 regulation of calcium absorption in the ileum, cecum and colon has also been reported [8 – 14]. The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is expressed in all segments of the small and large intestine [15 – 17] and two targets of vitamin D (the calcium binding protein calbindin-D9k and the epithelial calcium channel TRPV6) are present in all segments of mouse and rat intestine [18,19]. Thus, although calcium is absorbed most rapidly in the duodenum compared to other segments, 1,25(OH)2D3 action in the distal segments of the intestine also contributes to the calcium absorptive process.

1,25(OH)2D3 Regulated Transcellular Intestinal Calcium Absorption

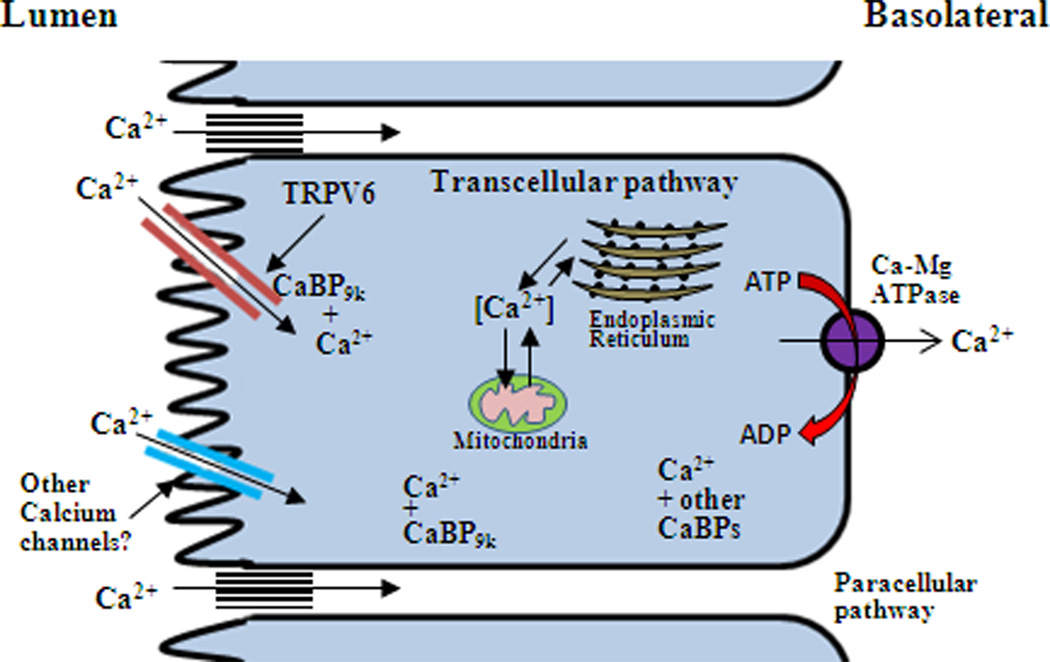

Transcellular calcium transport is believed to be comprised of three 1,25(OH)2D3 regulated steps: (1) the entry of calcium from the intestinal lumen across the brush border membrane, (2) the transcellular movement of calcium through the cytosol of the enterocyte and (3) the energy requiring extrusion of calcium against a concentration gradient at the basolateral membrane [3,4]. It has been reported that only 2 – 4 h after 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment to vitamin D deficient or normal animals is overall intestinal calcium absorption significantly increased [20; Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Time dependent effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on duodenal absorption of 47Ca in vitamin D deficient (top panel) and vitamin D replete (bottom panel) chicks. Chicks were injected (i.v.) with 1ug 1,25(OH)2D3 and duodenal calcium absorption was measured by the in situ ligated loop procedure. *Significant difference from zero time controls (p < 0.05). [from RH. Wasserman 2005 with permission; 3].

Although early studies noted that calcium uptake by brush border membrane vesicles isolated from vitamin D replete animals is enhanced compared to uptake by vesicles isolated from vitamin D deficient animals [21 – 23], the molecular basis of vitamin D dependent calcium entry was not known. In 1999 the apical epithelial calcium channel TRPV6 was cloned from rat duodenum, suggesting one mechanism of calcium entry [24]. TRPV6 is a membrane protein containing six transmembrane domains, a putative N-linked glycosylation site and a long C terminal tail [24,25]. TRPV6 is expressed in villi tips but not in villi crypts and is strongly calcium selective [25]. Calmodulin associates with the C terminal end of TRPV6 enabling acceleration of the rate of TRPV6 current inactivation [26]. Association of TRPV6 with S100A10-annexin 2 complex and Rab11a has been reported to be required for targeting and retention of TRPV6 to the plasma membrane and recycling of TRPV6 respectively [27, 28]. These TRPV6 associated proteins may represent additional components of regulated calcium entry into the intestinal cell. TRPV6 and the calcium binding protein calbindin-D9k are colocalized in the intestine and both are induced by 1,25(OH)2D3, under low calcium conditions and at weaning [29]. In VDR KO mice, TRPV6 mRNA is reduced in the duodenum by more than 90% and there is a 50% reduction in calbindin-D9k mRNA [30, 31]. These studies provide indirect evidence for a role of TRPV6 and calbindin-D9k in 1,25(OH)2D3 regulated intestinal calcium absorption. However, studies in TRPV6 knock out (KO) mice as well as in calbindin-D9k KO mice indicate that active calcium transport still occurs in these mice, suggesting compensation by other calcium channels and other calcium binding proteins [32 – 34]. Although TRPV6 may be redundant, transgenic mice overexpressing TRPV6 in the intestine have been reported to develop hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria and soft tissue calcification, indicating a direct role for TRPV6 in the process of intestinal calcium transport [35]. Transgenic expression of TRPV6 is accompanied by an increase in calbindin-D9k [35]. In addition, unlike TRPV6 or calbindin-D9k single KO mice which transport calcium in response to 1,25(OH)2D3 similar to wild type (WT) mice, 1,25(OH)2D3 mediated intestinal calcium transport is reduced by 60% in TRPV6/calbindin-D9k double KO mice [32]. Findings in the transgenic mice as well as in the double KO mice suggest that TRPV6 and calbindin-D9k can act together in certain aspects of the intestinal absorptive process. Early studies (prior to the identification of TPRV6) showed that a significant fraction of total intestinal calbindin is associated with intestinal brush borders and binds to “a specific protein”[36]. It is indeed possible, but has not as yet been investigated, that calbindin-D9k binds to TRPV6 and that a principal function of calbindin is as a modulator of TRPV6 calcium influx (facilitating high calcium transport rates by preventing calcium dependent inactivation). Only recently has it been reported that calcium binding proteins in addition to calmodulin can bind to calcium channels, indicating differential adjustment of calcium influx by different calcium binding proteins [37,38]. Calbindin-D9k may also act as a calcium buffer preventing toxic levels of calcium from accumulating in the intestinal cell. With regard to calcium in the cytosol, calcium may be bound to calbindin as well as to other calcium binding proteins. Calcium may also be sequestered by the endoplasmic reticulum and then could be released in the proximity of the basolateral membrane. At the basolateral membrane calcium is extruded by the intestinal plasma membrane ATPase (PMCA1b) [Fig. 2]. Previous studies have shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 and low calcium stimulate the synthesis of PMCA1b [39, 40]. Although it has been suggested that the sodium calcium exchanger present at the intestinal basolateral membrane (isoform NCX1) may also play a role in calcium extrusion, this cotransporter, at least in rat intestine, is not regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 [41].

Figure 2.

Model of vitamin D mediated intestinal calcium absorption. The traditional model of transcellular calcium transport consists of influx through an apical calcium channel (TRPV6), diffusion through the cytosol and active extrusion at the basolateral membrane by the plasma membrane ATPase (PMCA1b). Although entry of calcium has been reported to involve TRPV6, other calcium channels may also be involved. Calcium binding proteins including calmodulin and calbindin-D9k (CaBP9k) may be important for fine tuning calcium channel activity. In the cytosol calcium may be bound to calbindin as well as other calcium binding proteins. Calbindin as well as other calcium binding proteins may act to prevent toxic levels of calcium from accumulating in the cell. Calcium may also be sequestered by intracellular organelles ie. endoplasmic reticulum and mitochrondria which could also contribute to the protection of the cell against excessively high calcium. Increasing evidence supports regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 of paracellular calcium transport.

Effect of Other Hormones (Estrogen, Prolactin, Glucocorticoids) and the Effect of Aging on Active Intestinal Calcium Transport

During pregnancy and lactation active intestinal calcium transport is increased [42 – 44]. It has been reported that estrogens and prolactin, independent of vitamin D, stimulate active intestinal calcium transport [45,46]. Mechanisms include induction of TRPV6 by estrogen via estrogen receptor α and induction of TRPV6 by prolactin [45,47]. Prolactin also has cooperative effects with 1,25(OH)2D3 in induction of intestinal calcium transport genes and intestinal calcium transport [47]. In addition, prolactin has been reported to stimulate the transcription and expression of 1α(OH)ase [47].

Glucocorticoid treatment has been associated with bone loss leading to osteoporosis [48]. In addition to direct effects on bone, glucocorticoid treatment has been reported to result in decreased intestinal calcium transport which is associated with a decrease in TRPV6 and calbindin-D9k [49,50]. It has been suggested that the effect of glucocorticoids on duodenal calcium transporters can be independent of vitamin D [49, 51].

In aging there is a decrease in intestinal calcium absorption, increased PTH and age related bone loss [52, 53]. The decline in intestinal calcium absorption is correlated to a decrease in the expression of TRPV6 and calbindin-D9k (with no change or a small change in the concentration of intestinal VDR) [54 – 57]. It has been suggested that resistance of the intestine to 1,25(OH)2D3 action contributes to the age related decrease in net dietary calcium absorption, secondary hyperparathyroidism and bone loss [53, 56]. A better understanding the molecular basis of the calcium absorptive process, including the identification of novel proteins involved in various steps in this process, may lead to the identification of drug targets that could offset age and glucocorticoid related depression of calcium absorption.

Paracellular Intestinal Calcium Absorption

In addition to transcellular transport of calcium, calcium is also absorbed by the paracellular pathway that occurs through tight junctions and structures present within the intercellular spaces. The paracellular pathway functions throughout the length of the intestine but predominates in the more distal regions when dietary calcium is adequate or high [4]. Paracellular intestinal transport and its regulation by vitamin D, which has been a matter of debate [4, 58], remain much less defined compared to vitamin D mediated transcelluar transport of calcium. Claudins, a protein family of 24 members ranging in molecular weight from 20 – 27 kDa, are among the major components of tight junctions that form paracellular barriers and pores [59, 60]. Claudins were first purified and identified in 1998 [61]. Claudins are predicted to have 4 transmembrane helices. The first extracellular loop contains charged amino acids which determine the charge selectivity of paracellular transport [59, 60]. The expression pattern of claudins is variable among cell types. Some cells express a single claudin and others (for example intestine and kidney) express many [59, 60]. Studies by Fujita et al in 2008 showed that in VDR KO mice claudin-2 and -12 are downregulated in jejunum, ileum and colon compared to expression in WT mice (although claudin-7 and -15 are similarly expressed in VDR KO and WT mouse intestine) [62]. Using Caco-2 cells, 1,25(OH)2D3 was found to induce claudin-2 and -12 and knock down of these claudins impaired 1,25(OH)2D3 induced transport, supporting regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 of paracellular calcium transport [62]. Additional evidence supporting 1,25(OH)2D3 regulation of paracellular transport is provided by in vivo studies showing that non saturable as well as saturable intestinal calcium transport is enhanced by vitamin D [63, 64]. In the intestine 1,25(OH)2D3 has also been reported to downregulate cadherin-17 [32, 65, 66], a cadherin that is important for cell to cell contact [67] and aquaporin 8 (a tight junction channel) [65]. 1,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to have a direct effect on cadherin-17 transcription [66]. Although regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 of intercellular adhesion molecules has been shown and, at least in Caco-2 cells, alteration in the expression of specific claudins is associated with impaired 1,25(OH)2D3 induced calcium transport, further studies are needed to correlate regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 with paracellular properties. There is very little known related to the role of intercellular adhesion molecules in intestinal physiology. Although claudin-2 KO mice and cadherin-17 KO mice have been generated, their phenotype related to intestinal calcium absorption has not as yet been examined [68 and personal communication R. Gessner]. The discovery of intercellular adhesion molecules has provided for the first time a molecular level understanding of paracellular transport. In order to provide new insight into 1,25(OH)2D3 mediated regulation of the paracellular process further studies related to the physiological significance of intercellular adhesion molecules regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3, including studies with KO mice, are needed.

Role of 1,25(OH)2D3 in Protecting Against Mucosal Injury

In addition to intestinal calcium absorption, it has been suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier, protecting against mucosal injury. Evidence was obtained in studies showing that VDR KO mice are more susceptible to dextran sulfate sodium induced mucosal injury than WT mice [69]. Also, using Caco-2 monolayers, 1,25(OH)2D3 was found to induce tight junction proteins ZO-1, claudin-1 and claudin-2 and the adherin junction protein E-cadherin and to preserve the structural integrity of tight junctions in the presence of dextran sulfate sodium [69]. These studies suggest that, through upregulation of junction protein expression, 1,25(OH)2D3 maintains the integrity of the mucosal barrier. Junction proteins have multiple roles [59, 60]. They control paracellular transport but can also provide a barrier preventing exposure to bacteria and toxins. It is possible, depending on the physiologic input, that 1,25(OH)2D3, by regulating junction proteins, can regulate paracellular transport as well as maintain the integrity of the mucosal barrier.

1,25(OH)2D3 and Intestinal Phosphate Absorption

Although intestinal calcium absorption is the major biological function of vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D3 can also enhance intestinal absorption of dietary phosphate. In rats and humans phosphate absorption is highest in the jejunum (greater than the duodenum and greater than the ileum) [70, 71]. In mice the highest efficiency of phosphate absorption is in the ileum [72, 73]. It has been suggested that 1,25(OH)2D3 acts by affecting sodium dependent phosphate influx into the brush border membrane by regulating transcription of the intestinal type IIb sodium phosphate co-transporter (NaPi-IIb) [74]. However, this has been a matter of debate [75]. Although the mechanism is not clear, 1,25(OH)2D3 has been reported to regulate intestinal phosphate transport by an active, saturable process [76].

In summary

1,25(OH)2D3 mediated calcium absorption is more complex than the traditional three step model of transcellular calcium transport. Experimental evidence supports 1,25(OH)2D3 regulation of both transcellular active transport and paracellular absorption of calcium. In order to determine new approaches to sustain calcium balance, further studies are needed. Future directions include 1) identification of novel 1,25(OH)2D3 regulated proteins in different regions of the intestine 2) examination of calbindin-D9k as a modulator of calcium influx via TRPV6 and 3) correlation of the regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 of intercellular adhesion molecules with paracellular properties. A greater understanding of 1,25(OH)2D3 mediated intestinal calcium absorption will shed new light on both the control of calcium homeostasis and on the pathophysiology of impaired calcium absorption.

Highlights.

A major function of 1,25(OH)2D3 is intestinal calcium transport

The proximal and distal intestine contribute to the calcium absorptive process

TRPV6 and calbindin-D9k may act together in the calcium absorptive process

Active calcium absorption independent of TRPV6 or calbindin-D9k can occur

Evidence suggests that 1,25(OH)2D3 can also regulate paracellular calcium transport

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DK-38961-22

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DeLuca HF. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:S73–S87. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bikle D, Adams J, Christakos S. In: Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. 7th ed. Rosen C, editor. Washington, DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 2009. pp. 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasserman RH. In: Vitamin D. 2nd ed. Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux F, editors. San Diego: Academic; 2004. pp. 411–428. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasserman RH RH. J Nutr. 2004;134:3137–3139. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer CF. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1965;43:75–78. doi: 10.1139/y65-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus CS, Lengemann FW. J Nutr. 1962;77:155–160. doi: 10.1093/jn/77.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleet JC, Schoch RD. Chapter 19. In: Feldman D, Pike JW, Adams J, editors. Vitamin D. 3rd ed. San Diego: Academic; 2011. pp. 349–362. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Favus MJ. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:G147–G157. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.248.2.G147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vergne-Marini P, Parker TF, Pak CY, Hull AR, DeLuca HF, Fordtran JS. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:861–866. doi: 10.1172/JCI108362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer CF. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1965;43:75–78. doi: 10.1139/y65-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Favus MJ, Kathpalia SC, Coe FL, Mond AE. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:G75–G78. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1980.238.2.G75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barger-Lux MJ, Heaney RP, Recker RR. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;44:308–311. doi: 10.1007/BF02556309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DB, Walling MM, Levine BS, Gafter U, Silis V, Hodsman A, Coburn JW. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:G90–G96. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.240.1.G90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grinstead WC, Pak CY, Krejs GJ. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:G189–G192. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.247.2.G189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stumpf WE, Sar M, Reid FA, Tanaka Y, DeLuca HF. Science. 1979;206:1188–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.505004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue Y, Fleet JC. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1317–1327. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirst MA, Feldman D. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:315–319. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teerapornpuntakit J, Dorkkam N, Wongdee K, Krishnamra N, Charoenphandhu N. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E775–E786. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90904.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W, Na T, Wu G, Jing H, Peng JB. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36586–36596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasserman RH, Fullmer CS. J Nutr. 1995;125:1971S–1979S. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_7.1971S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bikle DD, Munson S, Zolock DT. Endocrinology. 1983;113:2072–2080. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-6-2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bikle DD, Morrissey RL, Zolock DT. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:2322–2328. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.11.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontaine O, Matsumoto T, Goodman DB, Rasmussen H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:1751–1754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng JB, Chen XZ, Berger UV, Vassilev PM, Tsukaguchi H, Brown EM EM, Hediger MA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22739–22746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng JB, Brown EM, Hediger MA. News Physiol Sci. 2003;18:158–163. doi: 10.1152/nips.01440.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derler I, Hofbauer M, Kahr H, Fritsch R, Muik M, Kepplinger K, Hack ME, Moritz S, Schindl R, Groschner K, Romanin C. J Physiol. 2006;577:31–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Graaf SF, Hoenderop JG, Gkika D, Lamers D, Prenen J, Rescher U, Gerke V, Staub O, Nilius B, Bindels RJ. EMBO J. 2003;22:1478–1487. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van de Graaf SF, Chang Q, Mensenkamp AR, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:303–312. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.303-312.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song Y, Peng X, Porta A, Takanaga H, Peng JB, Hediger MA, Fleet JC, Christakos S. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3885–3894. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Cromphaut SJ, Dewerchin M, Hoenderop JG, Stockmans I, Van Herck E, Kato S, Bindels RJ, Collen D, Carmeliet P, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13324–13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231474698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, Demay MB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9831–9835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benn BS, Ajibade D, Porta A, Dhawan P, Hediger M, Peng JB, Jiang Y, Oh GT, Jeung EB, Lieben L, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Christakos S. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3196–3205. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutuzova GD, Sundersingh F, Vaughan J, Tadi BP, S.E. Ansay SE, Christakos S, DeLuca HF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19655–19659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akhter S, Kutuzova GD, Christakos S, DeLuca HF. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui M, Fleet JC. J Bone Mineral Res. 2010;25:S59. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimura F, Wasserman RH. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1964–1972. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-5-1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harteneck C. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:303–310. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee D, Obukhov AG, Shen Q, Liu Y, Dhawan P, Nowycky MCMC, Christakos S. Cell Calcium. 2006;39:475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai Q, Chandler JS, Wasserman RH, Kumar R, Penniston JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1345–1349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghijsen WE, Van Os CH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;689:170–172. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghijsen WE, De Jong MD, Van Os CH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;730:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(83)90320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halloran BP, DeLuca HF. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:G473–G479. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1980.239.6.G473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boass A, Toverud SU, Pike JW, Haussler MR. Endocrinology. 1981;109:900–907. doi: 10.1210/endo-109-3-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brommage R, Baxter DC, Gierke LW. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G631–G638. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.4.G631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Cromphaut SJ, Rummens K, Stockmans I, Van Herck E, Dijcks FA, Ederveen AG, Carmeliet P, Verhaeghe J, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1725–1736. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pahuja DN, DeLuca HF. Science. 1981;214:1038–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.7302575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ajibade DV, Dhawan P, Fechner AJ, Meyer MB, Pike JW, Christakos S. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2974–2984. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patschan D, Loddenkemper K, Buttgereit F. Bone. 2001;29:498–505. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00610-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huybers S, Naber TH, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G92–G97. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00317.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee GS, Choi KC, Jeung EB. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290(296) doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00232.2005. E299-307.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feher JJ, Wasserman RH. Endocrinology. 1979;104:547–551. doi: 10.1210/endo-104-2-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ledger GA, Burritt MF, Kao PC, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL, Khosla S. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:3304–3310. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.11.7593443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pattanaungkul S, Riggs BL, Yergey AL, Vieira NE, O'Fallon WM, Khosla S. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4023–4027. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown AJ, Krits I, Armbrecht HJ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;437:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Abel M, Huybers S, Hoenderop JG, Van der Kemp AW, van Leeuwen JP, Bindels RJ. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F1177–F1183. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00038.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood RJ, Fleet JC, Cashman K, Bruns ME, DeLuca HF. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3843–3848. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.9.6176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halloran BP, Portale AA. In: Vitamin D. Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux FH, editors. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. pp. 823–838. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pansu D, Bellaton C, Bronner F. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:G32–G37. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.240.1.G32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:403–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Angelow S, Ahlstrom R, Yu AS. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F867–F876. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90264.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1539–1550. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujita H, Sugimoto K, Inatomi S, Maeda T, Osanai M, Uchiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Wada T, Kojima T, Yokozaki H, Yamashita T, Kato S, Sawada N, Chiba H. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1912–1921. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wasserman RH, Kallfelz FA. Am J Physiol. 1962;203:221–224. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.203.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dostal LA, Toverud SU. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:G528–G534. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.246.5.G528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kutuzova GD, Deluca HF. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;432:152–166. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Christakos S, Dhawan P, Ajibade D, Benn BS, Feng J, Joshi SS. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wendeler MW, Drenckhahn D, Gessner R, Baumgartner W. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muto S, Hata M, Taniguchi J, Tsuruoka S, Moriwaki K, Saitou M, Furuse K, Sasaki H, Fujimura A, Imai M, Kusano E, Tsukita S, Furuse M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8011–8016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912901107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, Ning G, Sun J, Hart J, Bissonnette M, Li YC. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208–G216. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00398.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee DB, Walling MW, Corry DB. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1986;251:G90–G95. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.251.1.G90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davis GR, Zerwekh JE, Parker TF, Krejs GJ, Pak CY, Fordtran JS. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:908–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marks J, Srai SK, Biber J, Murer H, Unwin RJ, Debnam ES. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:531–537. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Radanovic T, Wagner CA, Murer H, Biber J. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G496–G500. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00167.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu H, Bai L, Collins JF, Ghishan FK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C487–C493. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00412.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Capuano P, Radanovic T, Wagner CA, Bacic D, Kato S, Uchiyama Y, St-Arnoud R, Murer H. J. Biber. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C429–C434. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00331.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams KB, DeLuca HF. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1917–E1921. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00654.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]