Abstract

Background

Some patients who undergo lower extremity bypass (LEB) for critical limb ischemia ultimately require amputation. The functional outcome achieved by these patients after amputation is not well known. Therefore, we sought to characterize the functional outcome of patients who undergo amputation after LEB, and to describe the pre- and perioperative factors associated with independent ambulation at home after lower extremity amputation.

Methods

Within a cohort of 3,198 patients who underwent an LEB between January, 2003 and December, 2008, we studied 436 patients who subsequently received an above-knee (AK), below-knee (BK), or minor (forefoot or toe) ipsilateral or contralateral amputation. Our main outcome measure consisted of a “good functional outcome,” defined as living at home and ambulating independently. We calculated univariate and multivariate associations among patient characteristics and our main outcome measure, as well as overall survival.

Results

Of the 436 patients who underwent amputation within the first year following LEB, 224 of 436 (51.4%) had a minor amputation, 105 of 436 (24.1%) had a BK amputation, and 107 of 436 (24.5%) had an AK amputation. The majority of AK (75 of 107, 72.8%) and BK amputations (72 of 105, 70.6%) occurred in the setting of bypass graft thrombosis, whereas nearly all minor amputations (200 of 224, 89.7%) occurred with a patent bypass graft. By life-table analysis at 1 year, we found that the proportion of surviving patients with a good functional outcome varied by the presence and extent of amputation (proportion surviving with good functional outcome = 88% no amputation, 81% minor amputation, 55% BK amputation, and 45% AK amputation, p = 0.001). Among those analyzed at long-term follow-up, survival was slightly lower for those who had a minor amputation when compared with those who did not receive an amputation after LEB (81 vs. 88%, p = 0.02). Survival among major amputation patients did not significantly differ compared with no amputation (BK amputation 87%, p = 0.14, AK amputation 89%, p = 0.27); however, this part of the analysis was limited by its sample size (n = 212). In multivariable analysis, we found that the patients most likely to remain ambulatory and live independently despite undergoing a lower extremity amputation were those living at home preoperatively (hazard ratio [HR]: 6.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.94–49, p = 0.058) and those with preoperative statin use (HR: 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2–2.1, p = 0.003), whereas the presence of several comorbidities identified patients less likely to achieve a good functional outcome: coronary disease (HR: 0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.9, p = 0.003), dialysis (HR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9, p = 0.02), and congestive heart failure (HR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8, p = 0.005).

Conclusions

A postoperative amputation at any level impacts functional outcomes following LEB surgery, and the extent of amputation is directly related to the effect on functional outcome. It is possible, based on preoperative patient characteristics, to identify patients undergoing LEB who are most or least likely to achieve good functional outcomes even if a major amputation is ultimately required. These findings may assist in patient education and surgical decision making in patients who are poor candidates for lower extremity bypass.

INTRODUCTION

Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease represents a major health care concern for the American population, affecting over 12 million patients, and manifests in its most severe form as critical limb ischemia (CLI) in nearly 1 million elderly Americans. 1 A recent study published in Circulation estimated that the economic burden of CLI patients alone was over 3.1 billion dollars annually in the United States, because of the high incidence of limb loss and the need for long-term assisted care.2 While the development of new treatment modalities in the last decade has resulted in a rise in endovascular approaches to peripheral arterial disease, with an apparent modest decline in resultant amputations, it remains that over 100,000 major (above- or below-knee) amputations are still performed annually in Medicare patients.3 For many patients suffering from CLI, undergoing a major lower extremity amputation remains a feared and realistic possibility, especially among high-risk subgroups such as African Americans,4 those of low socioeconomic status, and those with severe diabetes mellitus, dialysis dependence, or older age.5–8

However, despite such a large number of amputees from CLI, functional outcomes after major lower extremity amputation have not been well described. Most evidence consists of single-institution retrospective reviews, and important patient determinants, such as mortality, ambulation status, independent living status, and progression to higher-level amputation, have yet to be explored in broad, multicenter settings.9–11 Little high-quality data exist to guide the expectations of patients and surgeons, both in terms of the functionality CLI patients can realistically expect to achieve after surgery and which patient-related factors determine the extent of their rehabilitation.

Therefore, to better delineate the functional outcomes after major lower extremity amputation, as well as to identify the patient-level factors associated with achieving good functional status even in the setting of a major amputation, we studied patients who underwent lower extremity amputation after failed attempt at revascularization in the Vascular Study Group of New England (VSGNE). This dataset is well suited to address these questions, as the VSGNE contains extensive patient-level details along with 1-year functional outcomes in a broad sample of patients undergoing lower extremity bypass (LEB) from both community and academic institutions.

METHODS

Subjects and Database

We used data that were collected prospectively within the VSGNE. This cooperative quality improvement initiative was developed in 2002 to include both community and academic medical centers to study regional outcomes in vascular surgery and has grown to include 19 hospitals and over 90 vascular surgeons. Details on this registry have been published previously,12 and further information can be obtained at www.vsgne.org. The Institutional Review Board at Dartmouth Medical School reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Only patients who underwent open infrainguinal bypass procedures were included in our study population. Inflow for the bypasses included iliac, femoral, or popliteal vessels. Bypass targets could be above-knee, below-knee, popliteal, tibial, or pedal vessels. Also included in the analysis were patients who underwent concomitant endovascular lower extremity procedures, such as angioplasty or stent, at the time of the bypass. LEB could be performed in an in situ fashion with reversed vein, vein cuff or adjuncts, or with prosthetic conduit.

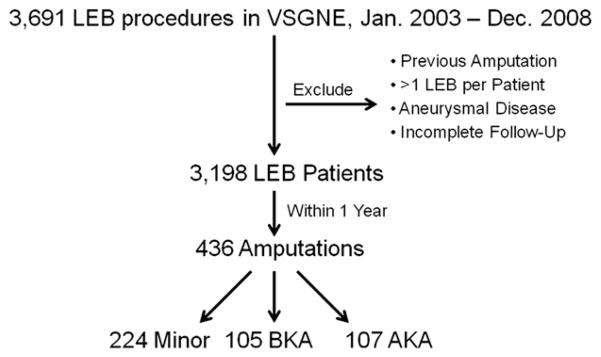

Defining the Cohort and Exposure

Our unit of analysis was the patient. We identified 3,691 LEB procedures performed between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2008. For this analysis, we selected only the first LEB procedure performed on an individual patient to avoid analytic confounding secondary to within-patient dependence. It has been shown that multiple bypass grafts in the same person do not act independently, and therefore, second and third bypass events for this study were excluded, as they would be confounded by the first.13 We also excluded patients who had a previous lower extremity amputation, underwent their LEB for aneurysmal disease, or lacked sufficient follow-up data (Fig. 1). This left us with 3,198 LEB patients. Of this cohort, 436 subjects underwent a lower extremity amputation within 1 year of their LEB. If patients underwent more than one amputation of the same limb, they were only included once and only their highest level of amputation occurring within the first year after LEB was analyzed. Patients with the exposure of interest in our analysis (those with amputation) were divided by level of amputation into the following categories: above-knee, below-knee, and minor amputations. We defined major amputation as either below-knee or above-knee amputations. Minor amputations were defined as those of forefoot or toe.

Fig. 1.

Patient selection. Representation of patient selection, exclusion, and creation of the investigated cohort.

For all patients, data on medical comorbidities, demographics, operative characteristics, and medication regimens were entered into the VSGNE data-base by trained surgeons, nurses, or clinical data abstractors. Over 70 variables were collected on each patient perioperatively and at 1-year follow-up as per the VSGNE published protocol.12

Outcome Measures

Using measures described in prior work,14 we designated our main outcome metric as a “good functional outcome” after lower extremity amputation. We defined a “good functional outcome” as the patient both ambulating independently or with assistance and living at home at times of follow-up. This was evaluated at time of hospital discharge and at 1 year after LEB. The VSGNE tracks ambulation and living status for patients before surgery, at hospital discharge, and at 1-year follow-up. Ambulation status is classified as independent, with assistance (use of cane, walker, prosthesis, or other assistive device), wheelchair-bound, or bedridden. Living status is characterized as living at home, in a nursing home, in a rehabilitation facility, or dead. Secondary outcome measures described are mortality, hospital length of stay, need for return to the operating room, and level of amputation in the setting of bypass graft patency versus thrombosis.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed patient characteristics at the time of LEB for variation across levels of subsequent amputation by chi-squared tests. We assessed the proportion of patients who achieved a good functional outcome at the time of hospital discharge and at long-term follow-up and compared these by amputation level. For the univariable analysis, the tests of significance used were chi-squared for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. As not all follow-up visits occurred at exactly 1 year after LEB, we used life-table analysis to examine variation in our main outcome at long-term follow-up. Mean follow-up time for the cohort was 374 days (range, 0–70 months). Level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

To assess which patient variables are related to a good functional outcome at hospital discharge after LEB in those patients who had or would progress to an amputation, we created a multivariable logistic regression model. Levels of association were described in odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values for categorical variables measured at discharge. Furthermore, we created a Cox proportional hazards model to analyze which patient variables at the time of LEB are associated with long-term functional outcome in those patients who had an amputation. Levels of association were described in hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI and p-values.

All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) and STATA (the STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2008, we studied 3,198 LEB patients within our cohort. The majority of patients who underwent LEB were male (69.6%), smoked (84%), and had hypertension (85.5%). Virtually all were of white race (99%). In terms of comorbidities, 36.7% had coronary disease, 48.1% had diabetes, and 7.1% were on dialysis. The extent of disease was also typical for a large cohort of patients undergoing LEB, with a little over one-third having claudication and 61.5% having either tissue loss or rest pain.

Amputations Following LEB

Within this cohort, 436 patients received a lower extremity amputation within 1 year of their LEB. Of note, only 16 (4%) of these amputations (8 fore-foot or toe, 2 below-knee, and 6 above-knee) occurred in patients who had an LEB performed for claudication. Before undergoing amputation, 25 (6%) patients underwent a thrombectomy/thrombolysis or revision for an occluded bypass graft. Of the 436 amputations performed, 224 were minor (forefoot or toe), 105 were below-knee, and 107 above-knee (Fig. 1).

These three groups were overall quite similar (Table I) regarding age, sex, and medical comorbidities. However, there were several differences in patient characteristics by level of amputation. For example, the rate of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was highest among patients who would undergo a minor or below-knee amputation (45.1% and 46.7%, respectively) and significantly lower among patients who would proceed to above-knee amputation (29.9%, p = 0.03 across groups). Additionally, patients who would progress to an above-knee amputation tended to have their LEB performed to a more proximal target. Thus, 22.4% of above-knee amputees had an above-knee popliteal target compared with only 14.3% of below-knee amputees and 16.1% of minor amputees, though the overall variation in choice of distal bypass target did not significantly vary across all groups (p = 0.14) (Table I).

Table I.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Underwent LEB n (%) |

Minor amputation n (%) |

Below-knee amputation n (%) |

Above-knee amputation n (%) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n = 3,198 |

Total n = 224 |

Total n = 105 |

Total n = 107 |

||

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Male gender | 2,225 (69.6) | 164 (73.2) | 67 (63.8) | 69 (64.5) | 0.12 |

| Right side | 1,654 (51.7) | 119 (53.1) | 55 (52.4) | 45 (42.1) | 0.15 |

| White race | 3,165 (99) | 222 (99.1) | 104 (99) | 104 (97.2) | 0.35 |

| Living home preoperatively | 3,078 (96.3) | 211 (94.2) | 104 (99) | 103 (96.3) | 0.15 |

| Independently ambulatory preoperatively | 2,517 (78.7) | 146 (65.2) | 67 (63.8) | 57 (53.3) | 0.09 |

| Age | |||||

| <40 | 19 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.33 |

| 40–50 | 157 (4.9) | 8 (3.6) | 9 (8.6) | 9 (8.4) | |

| 50–60 | 601 (18.8) | 27 (12.1) | 20 (19.1) | 18 (16.8) | |

| 60–70 | 909 (28.4) | 59 (26.3) | 27 (25.7) | 28 (26.2) | |

| 70–80 | 935 (29.2) | 72 (32.1) | 30 (28.6) | 32 (29.9) | |

| 80–90 | 523 (16.4) | 51 (22.8) | 18 (17.1) | 19 (17.8) | |

| 90–100 | 54 (1.7) | 6 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Smoking (prior or current) | 2,686 (84) | 166 (74.1) | 85 (81) | 85 (79.4) | 0.39 |

| Hypertension | 2,733 (85.5) | 197 (87.9) | 91 (86.7) | 94 (87.9) | 0.94 |

| COPD | 946 (29.6) | 60 (26.8) | 24 (22.9) | 37 (34.6) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes | |||||

| No diabetes | 1,659 (51.9) | 65 (29) | 30 (28.6) | 47 (43.9) | 0.03 |

| Non–insulin-dependent diabetes | 792 (24.8) | 58 (25.9) | 26 (24.8) | 28 (26.2) | |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 746 (23.3) | 101 (45.1) | 49 (46.7) | 32 (29.9) | |

| Coronary disease | 1,172 (36.7) | 91 (40.6) | 43 (41) | 48 (44.9) | 0.75 |

| Dialysis | 226 (7.1) | 28 (12.5) | 19 (18.1) | 18 (16.8) | 0.34 |

| Congestive heart failure | 529 (16.5) | 57 (25.4) | 21 (0.2) | 30 (28) | 0.38 |

| Tissue loss/rest pain | 1,966 (61.5) | 206 (92) | 96 (91.4) | 74 (69.2) | 0.17 |

| Previous arterial bypass | 745 (23.3) | 45 (20) | 34 (32.4) | 29 (27.1) | 0.05 |

| Operative characteristics of LEB | |||||

| Graft origin - common femoral artery | 2,133 (66.7) | 145 (64.7) | 64 (61) | 70 (65.4) | 0.75 |

| Graft recipient | |||||

| Above knee | 977 (30.6) | 36 (16.1) | 15 (14.3) | 24 (22.4) | 0.14 |

| Below knee | 1,173 (36.7) | 68 (30.4) | 23 (21.9) | 36 (33.6) | |

| Tibial | 755 (23.6) | 76 (33.9) | 42 (40) | 33 (30.8) | |

| Tarsal | 288 (9) | 44 (19.6) | 25 (23.8) | 14 (13.1) | |

| Anesthesia type | |||||

| General anesthesia | 2,511 (78.5) | 176 (78.9) | 77 (73.3) | 88 (82.2) | 0.08 |

| Epidural | 225 (7) | 22 (9.9) | 6 (5.7) | 6 (5.6) | |

| Spinal | 459 (14.4) | 25 (11.2) | 22 (21) | 13 (12.2) | |

| Conduit type | |||||

| Autogenous vein | 2,179 (68.1) | 182 (56.4) | 81 (25.1) | 60 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| Prosthetic | 1,018 (31.8) | 42 (37.2) | 24 (21.2) | 47 (41.6) | |

| Completion study performed | 1,940 (60.7) | 137 (61.2) | 84 (0.8) | 64 (59.8) | 0.002 |

| Concomitant ipsilateral proximal angioplasty/stent | 223 (7) | 14 (6.3) | 5 (4.8) | 7 (6.5) | 0.97 |

| Return to operating rooma | 400 (12.5) | 121 (54) | 48 (45.7) | 31 (29) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative myocardial infarction | 139 (4.4) | 15 (6.7) | 7 (6.7) | 8 (7.5) | 0.96 |

| Wound infection | 166 (5.2) | 18 (8) | 8 (7.6) | 12 (11.2) | 0.57 |

| Graft infection | 13 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.60 |

| Preoperative medication regimen | |||||

| Antiplatelet agent | |||||

| None | 841 (26.3) | 58 (25.9) | 32 (30.5) | 37 (34.9) | 0.29 |

| Aspirin use | 2,016 (63) | 146 (65.2) | 65 (61.9) | 56 (52.8) | |

| Clopidogrel use | 61 (1.9) | 9 (4) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Aspirin and clopidogrel use | 278 (8.7) | 11 (4.9) | 6 (5.7) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Preoperative statin use | 1,979 (61.9) | 121 (54) | 61 (58.1) | 57 (53.3) | 0.76 |

| Preoperative beta-blocker use | |||||

| No beta–blocker | 654 (20.5) | 28 (12.5) | 17 (16.4) | 25 (23.4) | 0.18 |

| Perioperative beta-blocker | 712 (22.3) | 45 (20.1) | 20 (19.2) | 19 (17.7) | |

| Chronic beta-blocker | 1,825 (57.1) | 151 (67.4) | 67 (64.4) | 63 (58.9) | |

Description of patient characteristics before and at the time of initial LEB surgery for the entire patient cohort. Comparison of patient characteristics among those who progressed to amputation, stratified by highest amputation level received.

LEB, lower extremity bypass.

Reasons for return to OR: infection, bleeding, thrombosis, revision.

Regarding functional status at baseline, most patients who underwent LEB ambulated independently at home before surgery. As shown in Table I, 96.3% of patients lived at home and 78.7% ambulated independently before their LEB procedure. Of the patients who underwent an amputation, a comparable 95.9% lived at home before their LEB. However, only 61.9% of amputees after LEB were ambulating independently before undergoing LEB (p < 0.001).

Functional Outcomes at Hospital Discharge Following LEB

An overall good functional outcome (ambulation with/without assistance and disposition to home) at hospital discharge after LEB was obtained by 45.1% of those who received a minor amputation, 45.7% of those who received a below-knee amputation, and 39.3% of those who received an above-knee amputation (p < 0.001). Specifically, those who underwent a below-knee amputation had a higher likelihood of being discharged to home versus those who received an above-knee amputation (50.5 vs. 43%, p = 0.34, Table II). Similarly, below-knee amputees were less likely to go to a nursing home after their LEB compared with above-knee amputees (16.2 vs. 24.3%, p = 0.23). Even those who only received a minor amputation were discharged to home only 47.8% of the time, whereas 73.6% of LEB patients that would not progress to amputation went home after their operation (p < 0.001).

Table II.

Functional outcomes at hospital discharge

| Outcome measure | No amputation mean (95% CI) or n (%)

|

Minor amputation mean (95% CI) or n (%)

|

Below-knee amputation mean (95% CI) or n (%)

|

Above-knee amputation mean (95% CI) or n (%)

|

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n = 2,755 | Total n = 224 | Total n = 105 | Total n = 107 | ||

| In-hospital outcome | |||||

| Length of stay (days) | 6.1 (5.9, 6.2) | 13.1 (12.1, 14.3) | 12 (10.6, 13.5) | 10.5 (9.3, 11.8) | <0.001 |

| Return to the operating room | 199 (7.2) | 121 (54) | 48 (45.7) | 31 (29) | <0.001 |

| Death | 50 (1.8) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (3.8) | 2 (1.9) | 0.47 |

| Discharge outcome | |||||

| Living status at discharge | n = 2,752 | n = 224 | n = 105 | n = 107 | |

| Home | 2,026 (73.6) | 107 (47.8) | 53 (50.5) | 46 (43) | <0.001 |

| Rehabilitation facility | 411 (14.9) | 57 (25.5) | 31 (29.5) | 33 (30.8) | |

| Nursing home | 265 (9.6) | 57 (25.5) | 17 (16.2) | 26 (24.3) | |

| Dead | 50 (1.8) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (3.8) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Ambulation at discharge | n = 2709 | n = 221 | n = 99 | n = 104 | |

| Independent | 1,593 (58.8) | 63 (28.5) | 20 (20.2) | 31 (29.8) | <0.001 |

| With assistance | 971 (35.8) | 120 (54.3) | 53 (53.5) | 44 (42.3) | |

| Wheelchair | 113 (4.2) | 26 (11.8) | 23 (23.2) | 24 (23.1) | |

| Bedridden | 32 (1.2) | 12 (5.4) | 3 (3) | 5 (4.8) | |

Outcomes at hospital discharge from LEB, comparing those who did not receive a subsequent amputation with those who necessitated an amputation, stratified by amputation level.

CI, confidence interval.

Regarding ambulation, below-knee and above-knee amputees were equally likely to ambulate independently or with assistance at hospital discharge (73.7 vs. 72.1%, p = 0.87). Patients who underwent a minor amputation were more likely to ambulate with or without assistance but less so than patients who did not have an amputation after LEB (82.8 vs. 94.6%, p < 0.001). For further details, please see Table II.

The timing of amputation following LEB was different across the different amputation levels. Of the 224 patients who had a minor amputation, 100% received their amputation before discharge from their LEB procedure. Conversely, most major amputations were performed after patients were discharged from their bypass procedure, as 63.8% of below-knee amputations and 83.2% of above-knee amputations occurred after hospital discharge (p < 0.001).

Functional Outcomes at 1-Year Follow-up

At 1 year after their LEB, the proportion of patients living at home had increased across all amputation groups (compared with the time of hospital discharge) (Table III). Those who had received an above-knee amputation, however, were significantly less likely to live at home when compared with those with a below-knee amputation (60.5 vs. 81%, p =0.004). Conversely, above-knee amputees were more likely to live in a nursing home 1 year after LEB than below-knee amputees (31.4 vs. 11.9%, p = 0.003). Minor amputees were less likely to live in a nursing home, but still twice as likely as those who did not progress to amputation after LEB (7.4 vs. 3.8%, p = 0.04).

Table III.

Functional outcomes at long-term follow-up

| Outcome measure | No amputation n (%)

|

Minor amputation n (%)

|

Below-knee amputation n (%)

|

Above-knee amputation n (%)

|

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n = 1,940 | Total n = 205 | Total n = 99 | Total n = 95 | ||

| Death within 1 year | 183 (9.4) | 31 (15.1) | 11 (11.1) | 8 (8.4) | 0.05 |

| Living status at 1 year follow-up | n = 1648 | n = 175 | n = 84 | n = 86 | |

| Home | 1,398 (84.8) | 127 (72.6) | 68 (81) | 52 (60.5) | <0.001 |

| Nursing home | 63 (3.8) | 13 (7.4) | 10 (11.9) | 27 (31.4) | |

| Dead | 187 (11.4) | 35 (20) | 6 (7.1) | 7 (8.1) | |

| Ambulation at 1-year follow-up | n = 1508 | n = 142 | n = 83 | n = 80 | |

| Independent | 1,320 (87.5) | 115 (81) | 22 (26.5) | 11 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| With assistance | 131 (8.7) | 21 (14.8) | 32 (38.6) | 22 (27.5) | |

| Wheelchair | 48 (3.2) | 5 (3.5) | 29 (34.9) | 45 (56.3) | |

| Bedridden | 9 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.5) |

Outcomes at 1-year follow-up from LEB, comparing those who did not receive a subsequent amputation with those who necessitated an amputation, stratified by amputation level.

Ambulation status at 1-year follow-up was significantly worse for major amputees. Of below-knee amputees, 65.1% were ambulatory with or without assistance, and only 41.3% of above-knee amputees ambulated independently or with assistance at long-term follow-up (p = 0.003). Above-knee amputees were therefore more likely to use a wheelchair compared with below-knee amputees (56.3 vs. 34.9%, p = 0.008). Minor amputees were overall much more likely to ambulate with or without assistance and even equaled the rate of ambulation achieved by LEB patients without subsequent amputation (95.8% and 96.2%, respectively, p = 0.9). Further details are delineated in Table III.

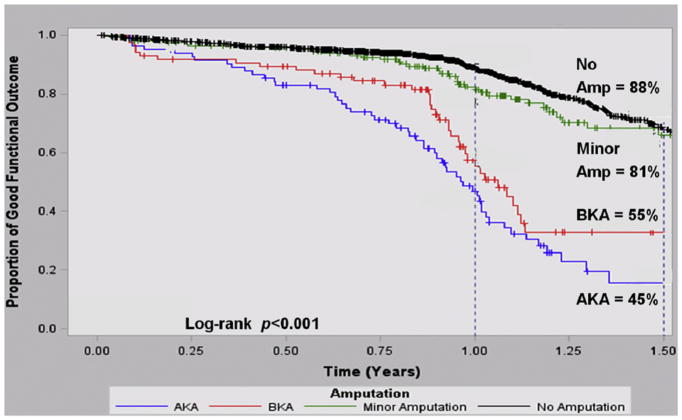

Using life-table analysis, we calculated the overall good functional outcome (ambulation with or without assistance at home) at long-term follow-up and stratified these results by amputation level (Fig. 2). Of the patients available at 1-year follow-up after their LEB, 88%of those who did not receive a subsequent amputation had a good functional outcome. A significantly lower rate of good functional outcome was achieved by those who only had a minor amputation (81 vs. 88%, p < 0.01). Comparatively, 55% of those who received a below-knee amputation and only 45% of those who underwent an above-knee amputation had a good functional outcome ( p=0.001 across groups).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot for good functional outcome. Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating the proportion of lower extremity bypass (LEB) patients who have a good functional outcome (independent ambulation at home), stratified by no amputation and amputation levels.

Multivariable Predictors of a Good Functional Outcome at Discharge

We constructed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify perioperative factors associated with a good functional outcome at hospital discharge after LEB. Variables associated with a good functional outcome in patients who had an amputation are depicted in Table IV. We found that the patients most likely to be ambulatory after LEB were those who ambulated independently before surgery (OR: 3.31, 95% CI: 2.02–5.45). The patient factors most closely associated with a poor functional outcome at hospital discharge included return to the operating room (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.28–0.71), age 70–79 years (OR: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.12–0.93), and age 80 years or greater (OR: 0.12, 95% CI: 0.01–0.35). In addition, CLI as an indication for LEB, as evidenced by tissue loss or rest pain, proved to have a negative association with a good functional outcome (OR: 0.09, 95% CI: 0.01–0.73), as did the presence of congestive heart failure (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.2–0.64).

Table IV.

Factors associated with good functional outcome at hospital discharge

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independently ambulatory preoperatively | 3.3 | 2.0–5.5 | <0.001 |

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| <50 | Reference | – | – |

| 50–59 | 0.8 | 0.3–2.4 | 0.69 |

| 60–69 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.8 | 0.39 |

| 70–79 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.9 | 0.04 |

| 80 or greater | 0.1 | 0.04–0.4 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.4 | 0.2–0.6 | <0.001 |

| Tissue loss/rest pain | 0.1 | 0.01–0.7 | 0.03 |

| Return to OR | 0.4 | 0.3–0.7 | <0.001 |

Area under the curve = 0.79.

These are risk factors determined by logistic regression to be significantly associated with a good functional outcome (independent ambulation at home) at the time of hospital discharge from LEB in patients who would progress to any level of amputation (minor, below-knee, or above-knee).

Multivariable Predictors of a Good Functional Outcome at 1-Year Follow-up

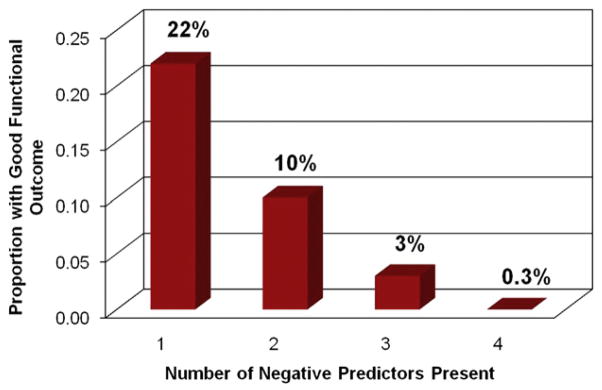

To identify patient-level factors associated with a good functional outcome at long-term follow-up, we constructed a Cox proportional hazards model. Variables linked to a good functional outcome in amputees at 1-year follow-up from index LEB are shown in Table V. We found that the patients most likely to ambulate with or without assistance at home in the long term were those who lived at home preoperatively (HR: 6.8, 95% CI: 0.94–49.2) and those who used a statin medication before surgery (HR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.17–2.11). Conversely, those patients who had a right-sided bypass or significant medical comorbidities were less likely to achieve a good functional outcome at long-term follow-up, as evidenced by the presence of coronary disease (HR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.45–0.85), dialysis (HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.31–0.9), and congestive heart failure (HR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.34–0.82). Figure 3 depicts that the presence of each of these negative predictors has an additive effect, such that patients who have all four predictors at the time of LEB have a 0.3% chance of achieving a good functional outcome when undergoing an amputation.

Table V.

Factors associated with good functional outcome at long-term follow-up

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right side | 0.7 | 0.54–0.96 | 0.02 |

| Living home preoperatively | 6.8 | 0.94–49.17 | 0.058 |

| Coronary disease | 0.6 | 0.5–0.9 | 0.003 |

| Dialysis | 0.5 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.02 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.5 | 0.3–0.8 | 0.005 |

| Preoperative statin use | 1.6 | 1.2–2.1 | 0.003 |

These are risk factors determined by Cox Proportional Hazards model to be significantly associated with a good functional outcome (independent ambulation at home) at 1-year follow-up from LEB in patients who would progress to any level of amputation (minor, below-knee, or above-knee).

Fig. 3.

Impact of negative predictors on outcome. Proportion of amputees with a good functional outcome that had one, two, three, or all four of the negative predictors present at time of LEB.

Secondary Outcomes

In-hospital Outcomes

We found that hospital length of stay after initial LEB was a mean of 10.5 days for those who received an above-knee amputation, 12 days for those who received a below-knee amputation, and 13.1 days for those who underwent a minor amputation (Table II). The patients who did not progress to amputation after LEB had a hospital length of stay half as long as those who would necessitate an amputation (mean, 6.1 days, p < 0.001 across groups). Return to the operating room after LEB occurred among 29% of those who received an above-knee amputation, among 45.7% of those who received a below-knee, and among 54% of those who would necessitate a minor amputation. In comparison, only 7.2% of patients who did not undergo an amputation after LEB returned to the operating room (p < 0.001 across groups).

Almost all minor amputations occurred in the setting of a patent LEB graft (89.7%). In contrast, 29.4% of below-knee and 27.2% of above-knee amputations took place in the setting of a patent LEB graft; the majority of major amputations were associated with graft thrombosis (70.6% and 72.8%, respectively).

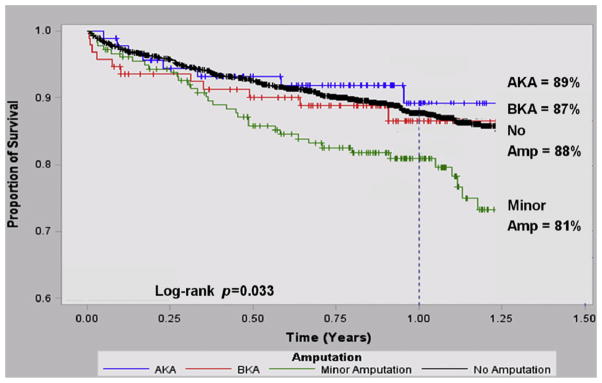

Survival

In-hospital death after LEB occurred in 1.9% of patients who received an above-knee amputation, in 3.8% of those who progressed to a below-knee amputation, in 1.3% of those who underwent a minor amputation, and in 1.8% of those who did not need an amputation after LEB (p = 0.465) (Table II).

We calculated long-term survival by life-table analysis, stratified by amputation level, as shown in Figure 4. Survival at 1 year after LEB was 88% for those who did not progress to amputation. Those who underwent a subsequent minor amputation had a significantly lower survival (81%, p = 0.02). Survival among below-knee amputees (87%, p = 0.14) and above-knee amputees (89%, p = 0.27) did not significantly differ when compared with those who did not receive an amputation; however, this part of the analysis was limited by the smaller group sizes for below-knee and above-knee amputees (n = 212 patients).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival. Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating the proportion of LEB patients who survived after LEB, stratified by no amputation and amputation levels.

DISCUSSION

In the current era of new diagnostic and therapeutic advances for CLI, the goal of limb preservation has become even more paramount. However, it remains that a given subset of patients suffer a prolonged recovery, significant economic burden, and limited functionality despite multiple revascularization attempts, even if they do, in fact, salvage their limb. The question thus arises whether we can identify patients at the time of revascularization that may achieve better functional outcomes in the setting of subsequent clinical failure of their procedure. This study presents initial answers to that question by describing 1-year functional outcomes of patients who lost their limb after infrainguinal bypass and by comparing that outcome among amputation levels. Secondly, we analyzed variables at the time of revascularization and their impact on functional outcome in the setting of subsequent amputation, which enables physicians to risk-stratify vascular patients before they are faced with limb loss.

In this multicenter regional analysis of vascular amputees, we demonstrated that subjects who undergo an amputation after LEB have worse functional outcomes than patients who do not undergo an amputation after LEB. Patients with a major amputation were nearly 50% less likely to have a good functional outcome at 1 year when compared with patients who did not have an amputation after LEB. Furthermore, we showed that the functional status achieved by amputees is directly related to the level of amputation. We were also surprised to discover that even a minor amputation can significantly decrease functionality, as shown by the 7% lower rate of patients who were ambulatory at home after a toe or forefoot amputation compared with those who underwent LEB alone.

Many believe that, whenever possible, a more distal amputation is preferred for improved function. Physiologic studies have demonstrated that a below-knee amputation versus an above-knee amputation is associated with lower energy expended with prosthetic use and therefore results in better ambulation rates.15 A single-center series of vascular amputees reported by Nehler et al.10 had similar findings. In reviewing 5 years of records of vascular patients who underwent a major amputation at either a university or Veterans Affairs hospital in Colorado, they found that 61% of below-knee amputees were ambulatory either indoors or outdoors 10.3 months after surgery. That number was much lower for above-knee amputees, at only 24%. They did not investigate the effect of a minor amputation on subsequent functionality. Taylor et al.16 reported a larger series of vascular amputees with longer follow-up from a single institution in South Carolina. Of their patients who underwent a below-knee, through-knee, or above-knee amputation, 55% maintained ambulation with or without prosthesis, and 73% maintained independent living status at 1-year follow-up. We found our regionally obtained ambulation and living rates in amputees after LEB to be remarkably similar, with 53% of major amputees ambulating with or without assistance and 71% living independently at 1 year.

In our cohort, functional status at the time of LEB had the highest predictive impact on functionality after a subsequent amputation. In subjects that ultimately underwent amputation, those that were ambulatory before LEB were three times more likely to ambulate on hospital discharge after LEB, and those who lived at home before LEB were seven times more likely to live independently in the first year after LEB. The impact of functionality before surgery on long-term ambulation rates has been equally described through the VSGNE registry for patients who undergo lower extremity revascularization 17 and should thus be greatly considered when evaluating any patient for LEB.

Our multivariable model demonstrated that patients with a right-sided LEB had a lower likelihood of achieving an overall good functional outcome following amputation. The statistical significance of this variable may be in part due to the relatively small sample size of our cohort as reflected in the wide range of the 95% CIs (0.54–0.96), which additionally approaches one. However, this finding may reflect a physiologic occurrence. Since 90%of individuals with normal gait have right leg dominance,18,19 it is possible that our result may show the larger inherent functional loss when operating on or amputating part of the dominant lower limb as opposed to the nondominant leg. Further work at a larger sample size would obviously be necessary to confirm this finding.

Furthermore, we outlined that negative predictors of a good functional outcome, such as coronary disease, congestive heart failure, older age, or dialysis dependence can inform patients and physicians at the time of LEB on a patient’s decreased likelihood of being ambulatory and living independent if faced with an amputation. Nehler and Taylor found similar relationships. Nehler et al. showed that older age was associated with lower rates of ambulation after amputation.10 Taylor et al. described that preoperative ambulation status, older age, level of amputation, and medical comorbidities such as end-stage renal disease were similarly associated with the functional outcome of amputees.16 Our analysis expands on these findings to show that the presence of each of these patient variables has a linear additive effect on long-term outcome, such that if all are present at the time of LEB, a patient has a virtually zero chance of ambulating and living independently after a subsequent amputation.

Lastly, we were surprised to find that long-term survival is not influenced by the level of major amputation. However, it is important to note that our patient cohort is a selected population of vascular amputees that were deemed healthy enough to undergo LEB. Survival following primary amputation is not directly informed by our study and remains a topic of debate. While a study by Cruz et al.11 demonstrated that actuarial survival after major amputation is not affected by amputation level in a vascular patient cohort from an Arkansas Veterans Affairs hospital, a larger series of vascular amputees reported by Aulivola et al.9 from a university hospital in Boston, MA, shows the opposite. They found that 74.5% of below-knee amputees were alive after 1 year compared with only 50.6% of above-knee amputees. This may represent a difference in underlying medical comorbidities, as their analysis included all amputations performed for vascular disease.

In certain high-risk patients, it is often difficult to determine whether a primary amputation or several extensive attempts at revascularization will provide a better functional outcome. We believe vascular surgeons can use the information presented herein as a preoperative counseling and decision-making tool in this setting. Elderly patients with congestive heart failure, for example, may learn of their lower chance at a good functional outcome after amputation and therefore prepare accordingly preoperatively. On the contrary, younger, healthier, and functionally independent patients that lack acceptable bypass conduit, a good distal target, or other important technical features may be better candidates for primary amputation, given their slightly higher likelihood of a good functional outcome thereafter.

Our study has several limitations. First, as mentioned previously, our cohort is limited to patients who have received an amputation only after previously having undergone an infrainguinal bypass. By nature of our dataset, primary amputations are not captured, and we are thus unable to directly compare how patients with a primary amputation fare differently than those with an amputation following LEB. We have therefore put into place the collection of primary amputations in the database and plan on such a comparison in a future analysis. Second, our database tracks patients for only 1 year and therefore does not allow us to comment on more long-term results. Third, the nature of our regional demographics limits our results to patients of primarily white race. Understanding that amputation rates are higher among other racial subsets,4 our future work will focus on a more diversified representation of racial and ethnic backgrounds. Fourth, we used two measures (ambulation and living status) to determine functionality. Although these may approach the overall functionality of the vascular patient after an intervention, they are limited in their scope and generalizability. The description of functional status (after both LEB procedures and amputations) and quality of life in vascular patients has undergone a recent evolution.20,21 Traditional outcome measures for LEB (mortality, graft patency, and limb salvage22–24) have recently been complemented by functional measures such as ambulation and living status.10,14 The VSGNE database was specifically designed to prospectively capture such functional outcomes, and thus, our main outcome metric of a “good functional outcome” combines these measures into one objective variable.

Lastly, while quality-of-life instruments, such as the short-form 36 or the VascuQol assessments, have been used on occasion in large randomized trials to examine patient functional outcomes,25,26 these instruments were not used in this study, as the cost associated with the administration of these surveys was prohibitive within our regional registry. Current assessment tools, such as the VascuQol or Nottingham Health Profile, focus on patients with claudication and may not be generalizable to patients with severe CLI. Disease-specific, validated quality-of-life instruments represent the next step in answering the question of when a primary amputation may provide an improved functional or quality outcome from the patient’s view instead of further attempt at revascularization. A better understanding of this decision will require a patient-centered measurement tool designed to evaluate patient-level quality of life, specifically in CLI patients who undergo surgery or amputation. Our future work will aim to develop these instruments.

CONCLUSIONS

In our region, functional outcomes following amputation after LEB are directly influenced by the level of amputation. Further, it is possible, based on preoperative patient characteristics, to identify those patients before LEB who are most likely to achieve good functional outcomes even in the setting of major amputation. More importantly, we are able to risk-stratify those patients at time of LEB who are least likely to achieve a good functional outcome when faced with a subsequent amputation. These findings may assist in patient education and surgical decision making in patients who are poor candidates for lower extremity revascularization.

Acknowledgments

The primary authors thank Yuanyuan Zao for help with the statistical analysis of this project. They also thank Michelle Bergeron, RN; Margaret Russell, RN; Robert Cambria, MD; Daniel Berges, MD; and Jen Eldrup-Jorgensen, MD, for their efforts in abstracting additional patient data that were originally unavailable.

P.P.G.’s work was supported by K08 Award from the NHLBI (1K08HL05676-01). The Vascular Study Group of New England is supported by a grant by from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), under Cooperative Agreement Award number 18-C-24 91674/1/01.

Footnotes

Presented at the 21st Annual Winter Meeting of the Peripheral Vascular Surgery Society, Steamboat Springs, CO, January 28-30, 2011.

References

- 1.Egorova NN, Guillerme S, Gelijns A, et al. An analysis of the outcomes of a decade of experience with lower extremity revascularization including limb salvage, lengths of stay, and safety. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:878–885.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peacock J, Keo H, Yu X, et al. The incidence and health economic burden of critical limb ischemia and ischemic amputation in Minnesota: 2005–2007. Circulation. 2009;120:S1148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodney PP, Beck AW, Nagle J, Welch HG, Zwolak RM. National trends in lower extremity bypass surgery, endovascular interventions, and major amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen LL, Hevelone N, Rogers SO, et al. Disparity in outcomes of surgical revascularization for limb salvage: race and gender are synergistic determinants of vein graft failure and limb loss. Circulation. 2009;119:123–130. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.810341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landry GJ. Functional outcome of critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:A141–A148. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schanzer A, Mega J, Meadows J, Samson RH, Bandyk DF, Conte MS. Risk stratification in critical limb ischemia: derivation and validation of a model to predict amputation-free survival using multicenter surgical outcomes data. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1464–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abou-Zamzam AM, Jr, Gomez NR, Molkara A, et al. A prospective analysis of critical limb ischemia: factors leading to major primary amputation versus revascularization. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virkkunen J, Heikkinen M, Lepantalo M, Metsanoja R, Salenius JP. Diabetes as an independent risk factor for early postoperative complications in critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aulivola B, Hile CN, Hamdan AD, et al. Major lower extremity amputation: outcome of a modern series. Arch Surg. 2004;139:395–399. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nehler MR, Coll JR, Hiatt WR, et al. Functional outcome in a contemporary series of major lower extremity amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz CP, Eidt JF, Capps C, Kirtley L, Moursi MM. Major lower extremity amputations at a Veterans Affairs hospital. Am J Surg. 2003;186:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cronenwett JL, Likosky DS, Russell MT, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Stanley AC, Nolan BW. A regional registry for quality assurance and improvement: the Vascular Study Group of Northern New England (VSGNNE) J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.012. discussion 101,102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marubini E, Braga M, Leite ML, Petroccione A, Pirotta N SINBA Group. “Within patient”-dependent outcomes in graft occlusion after coronary artery bypass. Control Clin Trials. 1993;14:296–307. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, et al. Determinants of functional outcome after revascularization for critical limb ischemia: an analysis of 1000 consecutive vascular interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.015. discussion 55,56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher SV, Gullickson G. Energy cost of ambulation in health and disability: a literature review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1978;59:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor SM, Kalbaugh CA, Blackhurst DW, et al. Preoperative clinical factors predict postoperative functional outcomes after major lower limb amputation: an analysis of 553 consecutive patients. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodney PP, Likosky DS, Cronenwett JL. Predicting ambulation status 1 year after lower extremity bypass. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1431–1439.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadeghi H, Allard P, Prince F, Labelle H. Symmetry and limb dominance in able-bodied gait: a review. Gait Posture. 2000;12:34–45. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matava MJ, Freehill AK, Grutzner S, Shannon W. Limb dominance as a potential etiologic factor in noncontact anterior cruciate ligament tears. J Knee Surg. 2002;15:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung J, Bartelson BB, Hiatt WR, et al. Wound healing and functional outcomes after infrainguinal bypass with reversed saphenous vein for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalbaugh CA, Taylor SM, Blackhurst DW, Dellinger MB, Trent EA, Youkey JR. One-year prospective quality-of-life outcomes in patients treated with angioplasty for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.04.045. discussion 302,303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517–538. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landry GJ, Moneta GL, Taylor LM, Jr, Edwards JM, Yeager RA, Porter JM. Long-term outcome of revised lower-extremity bypass grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:56–62. discussion 62,63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conte MS, Bandyk DF, Clowes AW, et al. Results of PREVENT III: a multicenter, randomized trial of edifoligide for the prevention of vein graft failure in lower extremity bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:742–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.12.058. discussion 751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forbes JF, Adam DJ, Bell J, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL) trial: health-related quality of life outcomes, resource utilization, and cost-effectiveness analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:43S–51S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazari FA, Gulati S, Rahman MN, et al. Early outcomes from a randomized, controlled trial of supervised exercise, angioplasty, and combined therapy in intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]