Abstract

Pythium aphanidermatum is one of the common causal pathogen of damping-off disease of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) grown in Manipur. A total of 110 indigenous Trichoderma isolates obtained from North east India were screened for their biocontrol activity which can inhibit the mycelial growth of P. aphanidermatum, the causal organism of damping-off in beans. Out of the total isolates, 32% of them showed strong antagonistic activity against P. aphanidermatum under in vitro condition and subsequently 20 best isolates were selected based on their mycelial inhibition capacity against P. aphanidermatum for further analysis. Different biocontrol mechanisms such as protease, chitinase, β-1,3-glucanase activity, cellulase and production of volatile and non-volatile compounds were also assayed. Based on their relative biocontrol potency, only three indigenous Trichoderma isolates (T73, T80 and T105) were selected for pot culture experiment against damping-off diseases in common beans. In greenhouse experiment, Trichoderma isolates T-105 significantly reduced the pre- and post-emergence damping-off disease incidence under artificial infection with P. aphanidermatum and showed highest disease control percentage.

Keywords: Biological control, Pythium aphanidermatum, Trichoderma isolates

Introduction

Modern agriculture is highly dependent on the use of chemical pesticides to control plant pathogens. Fungicides and fumigants commonly have drastic effects on the soil biota, as they are intentionally applied at much higher rates than herbicides and insecticides (Fraser 1994). These methods pollute the atmosphere, and are environmentally harmful, as the chemicals build up in the soil (Nannipieri 1994). Furthermore, the repeated use of such chemicals has encouraged the development of resistance among the target organisms (Goldman et al. 1994). Therefore, control of plant pathogens using microbial bioinoculants has been considered as a potential control strategy in recent years. For instance, integration of biocontrol agents with reduced doses of chemical agents has the potential to control plant pathogens with minimal impact on the environment (Chet and Inbar 1994). Therefore, search for these biological agents is increasing.

Beans (Vicia faba L.) is an important winter vegetable legume of North east India and considered as a meat and a skim milk substitute in diet for its high protein and nutritional quality (Chavan et al. 1989). Pythium damping-off is one of the major factors limiting the production of certain field crops in North east India. It is one of the major disease problems hampering the production of beans in this region. Pythium spp. are worldwide in distribution (Hendrix and Campbell 1973) that attack all stages of the various crops causing significant losses in yield. Trichoderma, a saprophytic fungus is known to be one of the best candidate of biocontrol agents. Modes of action of this fungus include mycoparasitism, antibiosis, competition for nutrients and space, tolerance to stress through enhanced root and plant development, solubilization and sequestration of inorganic nutrients, induced resistance, and inactivation of the pathogen’s enzymes (Scala et al. 2007). The antagonistic action of Trichoderma species against phytopathogenic fungi might be due to either by secretion of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes (Chet 1987; Di Pietro et al. 1993; Schirmbock et al. 1994) or by the production of antibiotics (Dennis and Webster 1971a, b; Claydon et al. 1987). They are known to be the most commonly used antagonists against Pythium aphanidermatum as they have more than one mechanism of action (Chet et al. 1981; Hadar et al. 1984; Krishnamurthy 1987; Kumar and Mukhopadhyay 1994, Shanmugam and Varma 1999; Hazarika et al. 2000; Manoranjitham et al. 2001). It also produces a large variety of volatile secondary metabolites such as ethylene, hydrogen cyanide, aldehydes and ketones which play an important role in controlling the plant pathogens (Vey et al. 2001). Although, exotic strains may be effective in diseases control, but, molecular technique-based evidence suggests that genotypes of beneficial microorganisms may be endemic to a biogeographical region (Cho Jae-Chang and Tiedji 2000). The endemic microbial pool of a region may contain highly efficient genotypes and is likely to perform better than the exotic strains. Due to the occurence of rich biodiversity in the Indo-Burma Biodiversity hot spot region, Manipur is likely to harbour useful Trichoderma isolates. So far, not much previous research has been done on the use of microbial agents for the control of damping-off diseases of beans in this region. Therefore, the present study describes the impact of different indigenous Trichoderma isolates in controlling of P. aphanidermatum the causal agent of damping-off disease in in vitro as well as in vivo conditions.

Materials and methods

Isolation of Trichoderma spp.

Soil samples were collected from agricultural fields of Imphal East and West districts of French bean growing fields of Manipur using TSM (Trichoderma selective medium) by the following modified method given by Tate (1995). Then, the colonies were transferred on PDA plates and incubated at 27 °C for 5–6 days followed by morphological identification based on colony characteristics (Gams and Bisset 1998) and microscopically according to the related literatures and identified on the basis of cultural and microscopic morphological characters (Barnett and Hunter 1972; Bissett 1991) using trinocular microscope.

Evaluation of antagonistic activity of Trichoderma species

The antagonistic effect of 110 Trichoderma isolates was evaluated against P. aphanidermatum in in vitro condition using dual culture technique (Coskuntuna and Özer 2008). Each Trichoderma spp. and P. aphanidermatum were cultured, separately, on PDA medium for 7 days at 25 °C. 4-day-old Trichoderma cultures were inoculated on one site of PDA plate and P. aphanidermatum cultures were inoculated at the opposite side of Petri dish and plates were incubated at 25 °C for 7 days. The colony interaction was assayed as percentage inhibition of the radial growth of the Trichoderma spp. towards the opponent antagonist using the following formula (Fokkema 1976):

where, A is the diameter of mycelial growth of pathogenic fungus in control and B is the diameter of mycelial growth of pathogenic fungus with Trichoderma isolate.

In vitro characterization of different biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma isolates

Production of volatile and non-volatile metabolites

Twenty selected Trichoderma isolates based on the mycelium inhibition assay against P. aphanidermatum were evaluated for the production of volatile inhibitory substances in in vitro conditions following the modified methods of Dennis and Webster (1971a). 5-mm disc of Trichoderma colony was inoculated centrally in petriplates containing PDA medium in triplicates. The petri plates were sealed at the edges and incubated at room temperature. After 5 days, the test pathogens were inoculated on fresh PDA and the lids of the petriplates inoculated with antagonist were replaced by the pathogen on PDA. The plates were fixed with cellophane-tape and incubated for another 7 days; whereas, control plates were inoculated with pathogen alone. Growth of P. aphanidermatum was measured after 5–6 days of incubation and the inhibition zones were recorded.

The production of non-volatile substances by the Trichoderma isolates against the test pathogen was studied using the method described by Dennis and Webster (1971b). Trichoderma isolates were inoculated in 100 ml sterilized potato dextrose broth (PDB) in 250 ml conical flasks and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C on a rotatory shaker set at 100 rpm for 15 days. The control flasks were not inoculated with any of the culture. The culture was filtered through Whatmann filter paper for removing mycelial mats and then sterilized by passing through 0.2 μm pore biological membrane filter. The filtrate was added to molten PDA medium (at 40 ± 3 °C) to obtain a final concentration of 10% (v/v). The PDA containing Petri dishes was inoculated with 5 mm mycelial plugs of the pathogens at the centre and plates were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C for 3 days or until the colony reached the plate edge. There were three replicates for each treatment. The inhibition zone of the mycelial growth in relation to growth of the controls was recorded.

Production of protease enzymes

Protease activity of Trichoderma isolates was determined using Skim milk agar medium (51.5/l) (Berg et al. 2002). Culture disc from 5- to 6-day-old Trichoderma cultures was inoculated on skim milk agar medium and incubated at 28 °C ± 2 °C for 3–4 days. Trichoderma with proteases activity gave a clearance zone around the colony indicating the production of protease enzymes.

Production of chitinase activity

Chitinase activity of the Trichoderma isolates was determined on chitin detection medium (Roberts and Selitrennikoff (1988).

Preparation of colloidal chitin: 5.0 g of chitin was added to 60 ml of conc. HCl (acid hydrolysis) by constant stirring using a magnetic stirrer at 4 °C and kept in refrigerator overnight. The resulting slurry was then added to 200 ml of ice-cold 95% ethanol and kept at 26 °C overnight (ethanol neutralization). Then it was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The pellet was repeatedly washed with sterile distilled H2O by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C until the smell of alcohol vanished. The final colloidal chitin was stored at 4 °C until further use.

Chitinase detection medium: The final chitinase detection medium per litre comprises 4.5 g colloidal chitin, 0.3 g magnesium sulphate, 3.0 g ammonium sulphate, 2.0 g potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 1.0 g citric acid monohydrate, 15 g agar, 0.15 g bromocresol purple and 200 μl of tween-80. The pH of the media was maintained at 4.7 and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. The fresh culture plugs of Trichoderma isolates to be tested for chitinase activity were inoculated into the sterile plates containing chitinase detection medium and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 2–3 days and observed for the coloured zone formation. Chitinase activity was identified due to the formation of purple coloured zone. The principle behind the formation of coloured zone is that the media is supplemented with a pH indicator dye, bromocresol purple which transforms the yellow colour of the media (in acidic here pH 4.7) into purple colour due to increase in pH. The pH increases because of the utilization of chitin by the Trichoderma and its breakdown into product N-acetyl glucosamine. Colour intensity and diameter of the purple coloured zone were taken as the criteria to determine the chitinase activity after 3 days of incubation.

Production of β-1,3-glucanases

For plate screening of β-1,3-glucanases activity, carboxy methyl cellulose agar (CMC agar) medium amended with laminarin was used according to the modified method given by El-Katatny et al. 2001. 1 l of CMCA contained 1 g of ammonium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.2 g of potassium chloride, 1 g of magnesium sulphate, 1 g of yeast extract and 1,000 ml of distilled water. A 6 mm culture disc was placed at the centre of the plate. Plates were incubated at 25 °C for 3 days. β-1,3-glucanases activity on the plates was observed by dipping in 0.1% congo red dye for 15–20 min followed by distaining with 1 N NaCl and then with 1 N NaOH for 15 min. The distaining was repeated twice. β-1,3-glucanase activity was recorded with the clearance zone formation.

Production of cellulase activity

To determine the production of cellulase activity from the Trichoderma isolates, 5 mm disc of Trichoderma cultures was inoculated on Czapek-mineral salt agar medium. 1 l of Czapek-mineral salt agar medium consist of 2.0 g of NaNo3, 1.0 g of K2HPO4, 0.5 g of MgSo4.7H20, 0.5 g of KCl, 5.0 g of CMC, 2.0 g of peptone, 20.0 g of agar and 1,000 ml of distilled H2O. Inoculated plates were incubated at 35 °C in an inverted position. After 2–5 days, the plates were flooded with 1% aqueous solution of hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide. The degree of cellulase activity production was observed according to the formation of a clearance zone formation around the colony (Aneja 2004).

After assessing the biocontrol properties exhibited by the selected 20 Trichoderma isolates under in vitro condition, only three isolates, T73, T80 and T105 were selected for further pot experiment under greenhouse conditions.

Antagonistic activity of the selected Trichoderma isolates in green house conditions

Based on various biocontrol potency exhibited by the indigenous Trichoderma isolates, three isolates viz. T73, T80 and T105 were selected for pot culture experiments against P. aphanidermatum under artificially infestation conditions. The experiment was designed under greenhouse conditions at IBSD, Imphal during May–August for 2 consecutive years in 2009–2010. Each pot was taken with 4 kg of sterilized, loamy, clay soil. 2 days before seedling, soil was infested with P. aphanidermatum at the rate of 5 g/kg soil. Simultaneously after 2 days of pathogen inoculation, soils were inoculated with Trichoderma isolates at 5 g/kg soil, and then pots were watered for 7 days before sowing. Six bean seeds were sown in each pot. Three pot replicates for each treatment. Pots were kept under greenhouse conditions till the end of the experiment. Disease incidence of pre-and post-emergence and survival (%) of bean plants were recorded after 15, 30 and 45 days, respectively. The percent disease incidence was calculated using the following formula.

|

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from all the experiments were analysed by analysis of variance ANOVA using SPSS Statistical Package. List significance difference (LSD) at 5% level of significance (P = 0.05) was used to compare the mean values of different treatments in the experiment.

Results

In vitro antifungal activity

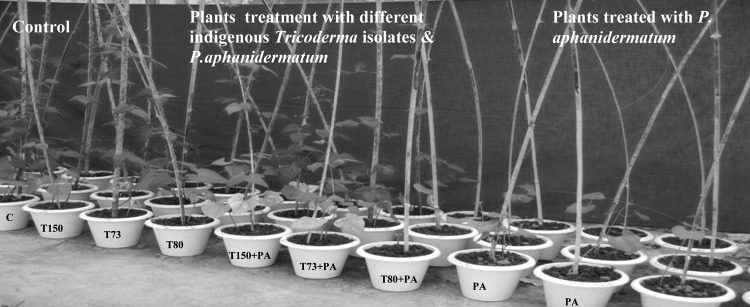

Out of the total Trichoderma isolates tested, 32% of them shows antifungal antagonistic activity in in vitro conditions against P. aphanidermatum the causal agents of damping-off disease in beans. Based on the dual plate assay results of mycelial growth inhibition, 20 potential Trichoderma isolates were selected for further characterization (Table 1; Fig. 1). Six isolates could significantly inhibit the external growth of P. aphanidermatum with the highest disease reduction percentage. The inhibition % was in the range of 4.16–84%. Maximum inhibition zone was exhibited by T105 (84%) while the lowest one was observed in T71 (4.16%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vitro antifungal activity of the selected Trichoderma isolates against P. aphanidermatum

| Sl. no. | Trichoderma isolates | Antifungal activity (inhibition zone in mm) Pythium aphanidermatum |

Disease incident % | Production of metabolites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile metabolites | Non-volatile metabolites | ||||

| 1 | T11 | 71.00 ± 2.08a | 11.25 | + | – |

| 2 | T21 | 48.33 ± 1.67c | 19.58 | – | – |

| 3 | T24 | 76.33 ± 1.86a | 15.41 | – | – |

| 4 | T37 | 42.33 ± 1.45c | 27.08 | – | – |

| 5 | T39 | 67.67 ± 1.45b | 15.41 | – | – |

| 6 | T41 | 62.67 ± 1.45b | 21.66 | – | – |

| 7 | T51 | 71.67 ± 0.89a | 10.41 | – | – |

| 8 | T61 | 70.00 ± 1.15a | 12.50 | – | – |

| 9 | T66 | 46.00 ± 1.00c | 42.5 | – | – |

| 10 | T68 | 49.00 ± 1.50c | 38.75 | – | – |

| 11 | T70 | 67.00 ± 1.08b | 16.25 | – | + |

| 12 | T71 | 12.33 ± 1.45d | 84.59 | – | – |

| 13 | T73 | 75.67 ± 1.20a | 5.41 | + | + |

| 14 | T77 | 48.33 ± 2.02c | 39.59 | – | – |

| 15 | T80 | 72.33 ± 1.45a | 9.59 | – | – |

| 16 | T83 | 42.33 ± 1.45c | 47.09 | – | + |

| 17 | T86 | 64.33 ± 2.33b | 19.59 | – | − |

| 18 | T89 | 40.00 ± 1.15c | 50.00 | + | + |

| 19 | T100 | 65.33 ± 1.45b | 18.34 | – | – |

| 20 | T105 | 76.67 ± 1.67a | 4.16 | + | + |

| 21 | Control | 80.00 ± 0.12a | 0 | – | – |

| LSD (P = 0.05) | 8.73 | ||||

Values are average of three replicates ± SEM

Values in the column followed by same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

Antagonistic activity of the Trichoderma islolate against the P. aphanidermatum.aTrichoderma isolate, bP. aphanidermatum

Production of volatile and non-volatile metabolites

After 7 days of incubation, the production of secondary metabolites was observed and it was found that only four Trichoderma isolates (T11, T73, T89 and T105) exhibited the production of volatile metabolites with maximum growth inhibition of P. aphanidermatum when compared to the other treatment; while, five Trichoderma isolates (T70, T73, T83, T89 and T105) showed the production of non-volatile compounds by inhibiting the growth of the P. aphanidermatum (Table 1).

Determination of different biocontrol enzymatic activity

The production of different types of hydrolytic enzymes by the selected 20 Trichoderma isolates was assayed. Results were recorded according to the diameter in mm produced in the enzyme detection plates.

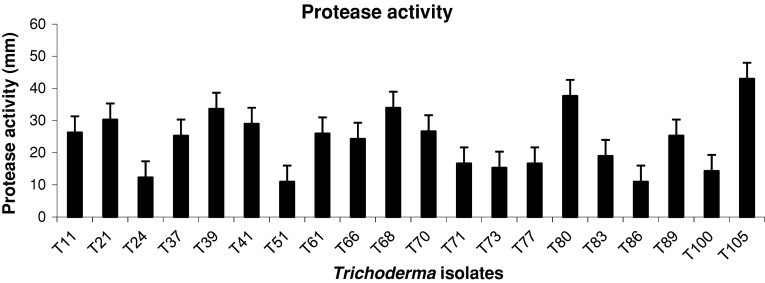

The protease activities produced by the different Trichoderma isolates range from 11 to 43 mm in diameter. The maximum activity was recorded in T105 (43 mm) followed by T80 (37.67 mm) and T68 (34 mm) while the least activity was recorded in T51 (11 mm) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Specific activity of protease from different selected Trichoderma isolates. (Each bar represents the average of three independent measurements)

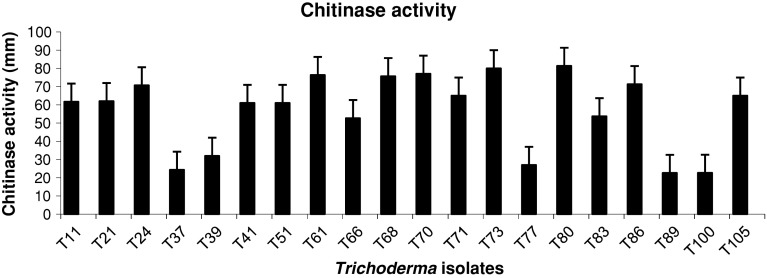

With the degree of the formation of purple colour zone on the chitin detection medium, the production of chitinase activity has been recorded. The chitinase activity of the selected 20 Trichoderma isolates varied from one another (Fig. 3). The highest activity was recorded in the case of T80 with a zone diameter of 81.33 mm followed by T73 (80 mm) and T61 (76.33 mm), while T89 produced minimum chitinase activity producing only 22.6 mm clearing zone diameter.

Fig. 3.

Specific activity of chitinase from different selected Trichoderma isolates. (Each bar represents the average of three independent measurements)

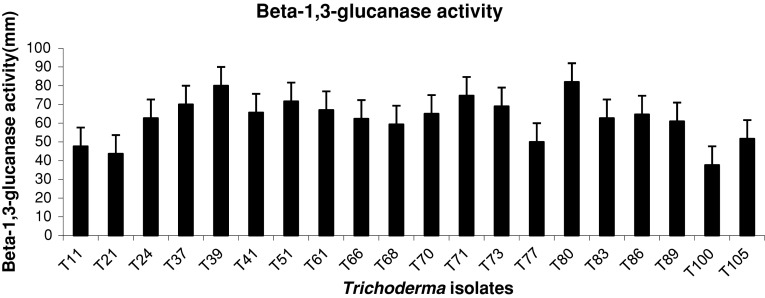

The data in Fig. 4 showed that T80 significantly produced maximum β-1,3-glucanase activity with 82 mm zone diameter which was followed by T39 (80 mm) and T73 (69 mm). Among the tested isolates, the least β1,3-glucanase activity was recorded in case of T100 (37.66 mm).

Fig. 4.

Specific activity of β-1,3-glucanase activity from different selected Trichoderma isolates. (Each bar represents the average of three independent measurements)

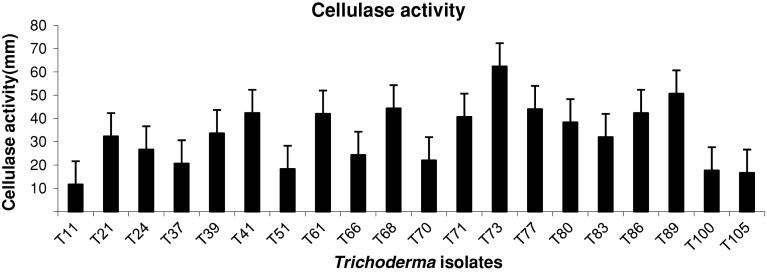

It is evident from the data in Fig. 5 that the highest cellulase activity was observed in case of T73 (62.33 mm), which was followed by T105 (50.67 mm) and T68 (44.33). The least cellulase activity was produced by T11 (11.67 mm).

Fig. 5.

Specific activity of cellulase activity from different selected Trichoderma isolates. (Each bar represents the average of three independent measurements)

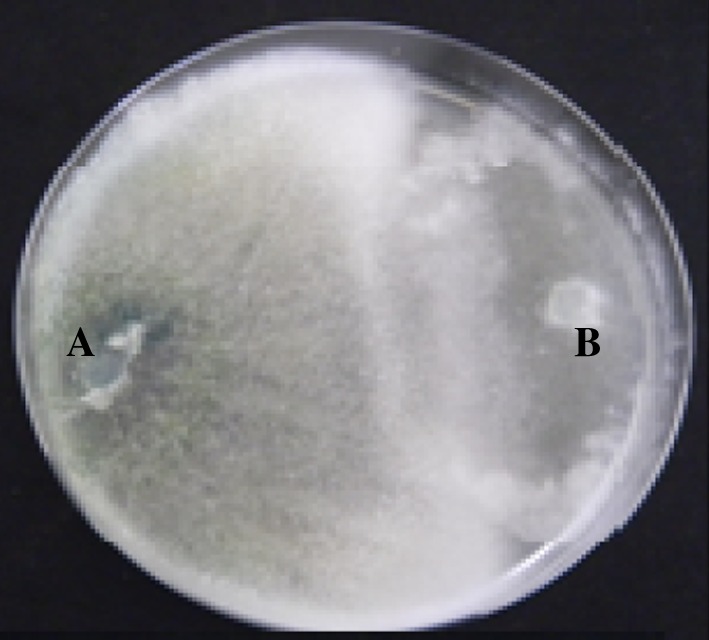

In greenhouse experiment

In controlled environmental conditions, soil treatments with T73, T80 and T105 significantly (P = 0.05) reduced the pre- and post-emergence damping-off disease incidence under artificial infection with P. aphanidermatum in greenhouse conditions (Table 2). The damping-off disease incidence at the pre-emergence caused by combined application of P. aphanidermatum and Trichoderma spp. was in the range of 9–22%. After 30 days of plantation, the growth patterns were observed and recorded. At this stage, T105 gave the highest reduction to disease incidence by 82.86%, followed by T73 (63.81%), and T80 (22.0%). At post-emergence stage, the disease incidence ranges from 5.8 to 8.2%. T105 gave the highest growth reduction of 90.72% to disease incidence followed by T73 (88.00%) and T80 (86.88%), respectively. The percentages of survival bean plants were in the range of 78.5–90.1 compared to 42.4% healthy bean plants in the control treatment. T105 gave 90.1% healthy plants, followed by T73 (87.2%), and T80 (78.5%), respectively (Table 2; Fig. 6). From this data, it is clear that the indigenous T105 isolates have a good potentiality of controlling the damping-off disease of beans caused by the P. aphanidermatum.

Table 2.

Effect of Trichoderma isolates treatments on the percentage of damping-off disease of bean plants under greenhouse condition (artificial infection)

| Trichoderma isolates | Disease assessment | Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damping-off in beans (by Pythium aphanidermatum) | Healthy plants (%) | ||||

| Pre-emergence | Post-emergence | ||||

| Incidence (%) | Reduction (%) | Incidence (%) | Reduction (%) | ||

| T73 | 22.0b | 58.09 | 7.5c | 88.00 | 87.2b |

| T80 | 19.0c | 63.81 | 8.2b | 86.88 | 78.5c |

| T105 | 9.0d | 82.86 | 5.8d | 90.72 | 90.1a |

| Control | 52.5a | 62.5a | 42.2d | ||

Means in each column followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to LSD test (P = 0.05)

Fig. 6.

Pot experiment of Trichoderma biocontrol efficacy in beans against P. aphanidermatum under greenhouse condition

Discussion

An important finding of the present study is the identification of indigenous Trichoderma isolates from the unique biodiversity hot spot zone of North east India as potential biocontrol agents. The results obtained indicate that the selected Trichoderma isolates can be a potential source of biocontrol agents for the control of damping-off disease in beans grown in this region which may be due to location specific and well adaptation with the existing environmental conditions of the region and also due to pathogen specificity. Maximum inhibition of the pathogen was observed with T105 (76.67 mm). Formation of inhibition zone against P. aphanidermatum in dual cultures could be explained on the basis of production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes by Trichoderma (El-Katatny et al. 2001). Fajola and Alasoadura (1975) found that culture filtrates of T. harzianum inhibit zoospore germination, germ tube elongation and mycelial growth of P. aphanidermatum causing the damping-off disease of tobacco. Formation of inhibition zone at the contact between Trichoderma and P. aphanidermatum in dual cultures could be explained on the basis of production of volatile and non-volatile metabolites as well as the production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes by Trichoderma (El-Katatny et al. 2001).

In the present study, we tested local Trichoderma isolates for the production of volatile and non-volatile compounds that can inhibit the growth of P. aphanidermatum in in vitro condition. From the result, it is evident that volatile compounds produced by Trichoderma suppress the mycelial growth of P. aphanidermatum and found effective when compared to the other treatments. The earlier studies also revealed that antimicrobial metabolites produced by Trichoderma are effective against a wide range of fungal phytopathogens e.g., Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, P. aphanidermatum, Curvularia lunata, Bipolaris sorokiniana and Colletotrichum gloeosporiodes (Xiao-Yan et al. 2006; Zivkovic et al. 2010).

The extracellular enzymes produced by Trichoderma isolates may be correlated with the antagonism. Results from the current study showed that most of the selected 20 Trichoderma isolates have given good enzymatic activities. Elad et al. (1982) reported that the isolates of T. harzianum, which were found to differ in their ability to attack Sclerotium rolfsii, Rhizoctonia solani and P. aphanidermatum, also differed in the levels of mycolytic enzymes produced by them. Trichoderma directly attacks the plant pathogen by excreting lytic enzymes such as chitinases, β-1,3-glucanases, proteases and cellulases (Elad et al. 1982; Haran et al. 1996) and also with the production of volatile and non-volatile metabolic compounds. In the present study, T105, T80. T80 and T73 isolates were observed to be the efficient producer of proteases, chitinases, β-1,3-glucanases and cellulases activity, respectively. Lorito et al. (1994) have shown the involvement of glucanases in mycoparasitism. Involvement of proteases in biocontrol processes has already been reported (Elad and Kapat 1999; Pozo et al. 2004). De marco and Felix (2002) observed that the biocontrol potential of an Indian Trichoderma isolates against C. perniciosa was due to protease activity. In the present study, T73, T89 and T86 were observed to be the efficient producer of cellulases enzymes. This might be one of the reasons for its biocontrol potentiality. As the cell wall of Pythium species is composed of cellulose and 1 β-1,3-glucan (Bartinicki-Garcia 1968), the enzymes produced by Trichoderma might be involved in hydrolysis of P. aphanidermatum cell wall during antagonism (Thrane et al. 1997). Lorito et al. (1994) reported the involvement of glucanases in mycoparasitism.

Our results revealed that the T73, T80 and T105 isolates, which were obtained from the rhizosphere soil of healthy bean plants, have been reported to have strong biocontrol activity against damping-off disease caused by P. aphanidermatum under in vitro as well as pot culture experiment thereby reducing the mycelial growth of the pathogenic fungi. Since the continuous use of chemical methods is not economical in long run thereby polluting the environment leaving harmful residues which may lead to development of resistant strains among the target organisms. Therefore, the above overall results indicated that the application of indigenous Trichoderma isolates in the pot experiment tended to reduce the incidence of pre- and post-emergence of damping-off disease of the beans (Table 2). These results agree with those recorded by Thrane et al. 1997. Biocontrol agents such as T73, T80 and T105 isolates used in the present study, may better be able to colonize the rhizosphere by inhibiting the pathogen community (Bennett and Whipps 2008b). Our results, based on soil treatments with the tested Trichoderma isolates demonstrated an effective reduction of incidence of damping-off disease in bean caused by P. aphanidermatum under in vitro as well as the pot experiment (El-kafrawy 2000; Gonzalez et al. 2005; Malik et al. 2005).

References

- Aneja KR. Experiment in microbiology, plant pathology and biotechnology. A text book. 4. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers; 2004. pp. 248–251. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett HL, Hunter BB. Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company; 1972. p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Bartinicki-Garcia S. Cell wall chemistry, morphogenesis and taxonomy of fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1968;22:87–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.22.100168.000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AJ, Whipps JM. Dual application of beneficial microorganisms to seed during drum priming. Appl soil Ecol. 2008;38:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2007.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg G, Krechel A, Ditz M, Sikora RA, Ulrich A, Hallmann J. Endophytic and ectophytic potato-associated bacterial communities differ in structure and antagonistic function against plant pathogenic fungi. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2002;51(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissett J. A revision of the genus Trichoderma II: infragenic classification. Can J Bot. 1991;69:2357–2372. doi: 10.1139/b91-297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan JK, Kute LS, Kadam SS. Broad bean-nutritional chemistry, processing and utilization. In: Salunkhe DD, Kadam SS, editors. CRC hand book of world legumes. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Chet I. Trichoderma-application, mode of action and potential as a biocontrol agent of soil borne plant pathogenic fungi. In: Chet I, editor. Innovative approaches to plant disease control. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chet I, Inbar J. Biological control of fungal pathogens. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1994;48:37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02825358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chet I, Harman GE, Baker R. Trichoderma hamatum, its hyphal interactions with Rhizoctonia solani and Pythium spp. Microb Ecol. 1981;7:29–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02010476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Jae-Chang, Tiedji JM. Biogeography and degree of endemicity of Fluorescent pseudomonas strains in soil. Appl Environ Microbial. 2000;66:5446–5448. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5448-5456.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claydon N, Allan M, Hanso JR, Avent AG. Antifungal alkyl pyrones of Trichoderma harzianum. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1987;88:503–513. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(87)80034-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coskuntuna A, Özer N. Biological control of onion basal rot disease using Trichodermaharzianum and induction of antifungal compounds in onion set following seed treatment. Crop Protection. 2008;27:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2007.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Marco JL, Felix CR. Characterization of a protease produced by a Trichoderma harzianum isolate which controls cocoa plant witches’ broom disease. BMC Biochemistry. 2002;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C, Webster J. Antagonistic properties of species groups of Trichoderma II. Production of volatile antibiotics. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1971;57:41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(71)80078-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C, Webster J. Antagonistic properties of species groups of Trichoderma I, production of non-volatile antibiotics. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1971;57:25–39. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1536(71)80077-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro A, Lorito M, Hayes C, Broadway K, Harman GE. Endochitinase from Gliocladium virens. Isolation, characterization, synergistic antifungal activity in combination with gliotoxin. Phytopathology. 1993;83:308–313. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-83-308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elad Y, Kapat A. The role of Trichoderma harzianum protease in the biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1999;105:177–189. doi: 10.1023/A:1008753629207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elad Y, Chet I, Henis Y. Degradation of plant pathogenic fungi by Trichoderma harzianum. Can J Microbiol. 1982;28:719–725. doi: 10.1139/m82-110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-kafrawy AA. Biological control of bean damping-off caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Egypt J Agric Res. 2000;80(1):57–70. [Google Scholar]

- El-Katatny MH, Gudelj M, Robra KH, Elnaghy MA, Gubitz GM. Characterization of a chitinase and an endo-β-1,3-glucanase from Trichoderma harzianum, Rifai T24 involved in control of the phytopathogen Sclerotium rolfsii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;56:137–143. doi: 10.1007/s002530100646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajola AO, Alasoadura SO. Antagonistic effects of Trichoderma harzianum on Pythium aphanidermatum causing the damping-off disease of tobacco in Nigeria. Mycopathologia. 1975;57(1):47–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00431179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema NJ. Antagonism between fungal saprophytes and pathogens on aerial plant surfaces. In: Dickinson CH, Preece TF, editors. Microbiology of aerial plant surfaces. London: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 487–505. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser PM. The impact of soil and crop management practices on soil macrofauna. In: Pankhurst CE, Doube BM, Gupta VVSR, Grace PR, editors. Soil biota-management in sustainable farming systems. Australia: CSIRO; 1994. p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Gams W, Bisset J. Morphology and identification of Trichoderma. In: Kubicek E, Harman GE, editors. Trichoderma and Gliocladium: basic biology, taxonomy and genetics. London: Taylor and Francis; 1998. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman GH, Hayes C, Harman GE. Molecular and cellular biology of biocontrol by Trichoderma spp. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:478–482. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez RM, Castellanos LG, Rames MF, Perez GG. Effectiveness of Trichoderma spp. for the control of seed and soil pathogenic fungi in bean crop. Fitosanidad. 2005;9(1):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hadar Y, Harman GE, Taylor AG. Evaluation of Trichoderma Koningii and T. hamatum from New York for biological control of seed rot caused by Pythium spp. Phytopathology. 1984;74:106–110. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-74-106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haran S, Schikler H, Chet I. Molecular mechanisms of lytic enzymes involved in the biocontrol activity of Trichoderma harzianum. Microbiology. 1996;142:2321–2331. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika DK, Sarmah R, Paramanick T, Hazarika K, Phookan AK. Biological management of tomato damping-off caused by Pythium aphanidermatum. Indian J Plant Pathol. 2000;18:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix FF, Campbell WA. Pythium as plant pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathology. 1973;81:738–741. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy AS (1987) Biological control of damping off disease of tomato caused by Pythium indicum. M.Sc. Ag. Thesis, TNAU, Coimbatore, pp 130

- Kumar DER, Mukhopadhyay AN. Biological control of tomato damping off by Gliocladium virens. J Biol Control. 1994;18:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lorito M, Hayes CK, Di Pietro A, Woo SL, Harman GE. Purification, characterization, and synergistic activity of a glucan-β-1,3-glucosidase and a N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase from Trichoderma harzianum. Phytopathology. 1994;84:398–405. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik G, Dawar S, Sattar A, Dawar V. Efficacy of Trichoderma harzianum after multiplication on different substrates in the control of root rot fungi. Int J Biol Biotechnol. 2005;2(91):237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Manoranjitham SK, Prakasam V, Rajappan K. Biocontrol of damping-off of tomato caused by Pythium aphanidermatum. Indian Phytopath. 2001;54:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nannipieri P (1994) The potential use of soil enzymes as indicators of productivity, sustainable framing systems In: Pankhurst CE, Doube BM, Gupta, VVSR, Grace PR (eds.) CSIRO, Australia, pp 238–244

- Pozo M, Baek JM, Garcia JM, Kenerley CM. Functional analysis of tvsp1, a serine protease—encoding gene in the biocontrol agent Trichoderma virens. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41:336–348. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WK, Selitrennikoff CP. Plant and bacterial chitinases differ in antifungal activity. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Scala F, Raio A, Zonia A, Lorito M. Biological control of fruit and vegetable diseases with fungal and bacterial antagonists: Trichoderma and Agrobacterium. In: Chincholkar SB, Mukerji KG, editors. Biological control of plant diseases. Binghamton: Howorth Press; 2007. pp. 150–190. [Google Scholar]

- Schirmbock M, Lorito M, Wang YL, Hayes CK, Arisan-Atac I, Scala F, Harman GE, Kubicek CP. Parallel formation and synergism of hydrolytic enzymes and peptaibol antibiotics, molecular mechanisms involved in the antagonistic action of Trichoderma harzianum against phytopathogenic fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4364–4370. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4364-4370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam V, Varma AS (1999) In vitro evaluation of certain fungicides against selected antagonists of Pythium aphanidermatum, the incitant of rhizome rot of ginger Abs. J Mycol Pl Pathol 28:70 Abs

- Tate RL. Variation in microbial activity in histosols and its relationship to soil moisture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;40:313–317. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.2.313-317.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrane C, Tronsmo A, Jensen DF. Endo-1,3-β-glucanase and cellulose from Trichoderma harzianum: purification and partial characterization, induction by and biological activity against plant pathogenic Pythium spp. Eur J Plant Pathology. 1997;103:331–344. doi: 10.1023/A:1008679319544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vey A, Hoagland RE, Butt TM (2001) Toxic metabolites of fungal biocontrol agents. Fungi as biocontrol agents: progress, problems and potential. In: Butt TM, Jackson CN (eds) CAB International, Bristol, pp 311–346

- Xiao-Yan S, Qing-Tao S, Shutao X, Xiu-lan C, Cai-Yun S, Yu-Zhong Z. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and high stability of Trochokonins from Trichoderma koningii SMF2 against plant pathogens against plant pathogens. FEMS Microbial LeM. 2006;260(2006):119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivkovic S, Stojanovic S, Ivanovic Z, Gavrilovic Tatjana Popovic V, Balaz J. Screening of antagonistic activity of microorganisms against Colletotrichum aculatum and Colletotrichum gloeosporiodes. Arch Biol Sci Belgrade. 2010;62(3):611–623. doi: 10.2298/ABS1003611Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]