Abstract

Objective

This study investigates how shared decision-making (SDM) is defined by African-American patients with diabetes, and compares patients’ conceptualization of SDM with the Charles model.

Methods

We utilized race-concordant interviewers/moderators to conduct in-depth interviews and focus groups among a purposeful sample of African-American patients with diabetes. Each interview/focus group was audio-taped, transcribed verbatim and imported into Atlas.ti software. Coding was done using an iterative process and each transcription was independently coded by two members of the research team.

Results

Although the conceptual domains were similar, patient definitions of what it means to “share” in the decision-making process differed significantly from the Charles model of SDM. Patients stressed the value of being able to “tell their story and be heard” by physicians, emphasized the importance of information sharing rather than decision-making sharing, and included an acceptable role for non-adherence as a mechanism to express control and act on treatment preferences.

Conclusion

Current instruments may not accurately measure decision-making preferences of African-American patients with diabetes.

Practice Implications

Future research should develop instruments to effectively measure decision-making preferences within this population. Emphasizing information-sharing that validates patients’ experiences may be particularly meaningful to African-Americans with diabetes.

Keywords: shared decision-making, patient-provider communication, diabetes, African-American

1. Introduction

Patient-centered communication and shared decision-making (SDM) have been increasingly advocated by health care providers and have been recognized as quality of care measures. The 2001 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Crossing the Quality Chasm included patient-centeredness as one of six key components of quality health care and has defined patient-centeredness as care that “establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they require to make decisions and participate in their own care” [1]. Clearly, shared decision-making is at the core of patient-centered care. SDM recognizes the importance of having patients actively involved in their own care, a concept which is fundamental to many chronic disease models [2]. Shared decision-making has also been positively associated with health outcomes such as improved diabetes control, preventive health services use, lowered blood pressure, and fewer hospitalizations [3–7].

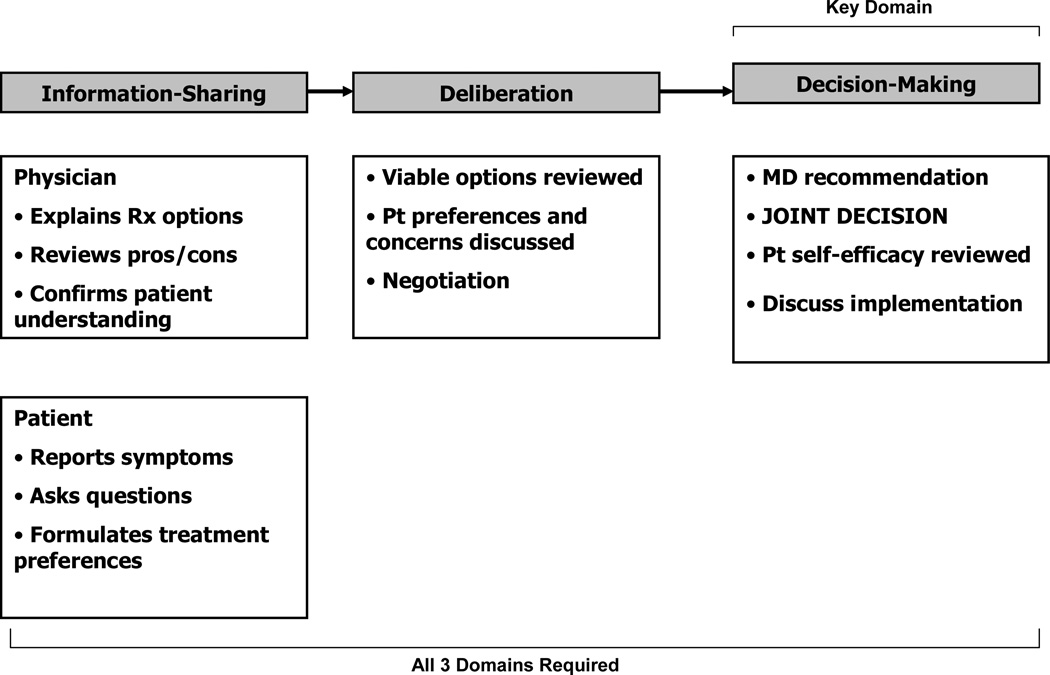

Despite this increased support of shared decision-making, there is currently no clear consensus about how SDM is defined or its central components; a recent systematic review found 31 distinct concepts used to describe SDM [8]. However, one-third of papers in the review utilized the SDM conceptual models based on the work of Cathy Charles and colleagues, which describe three sequential domains of SDM: information-sharing, deliberation and decision-making (Figure 1) [9–11].

Figure 1.

Charles Model of Shared Decision Making

In addition, there has been limited research exploring how patients conceptualize shared decision-making, but there is evidence of discrepancies between how SDM is conceptualized by researchers and how it is understood by patients [12–14]. For example, one population-based study in Wales compared in-depth interviews about decision-making preferences in cholesterol testing and diagnostic mammography to patients’ responses on the Control Preferences Scale (CPS) [15], an instrument measuring patient preferences for decision-making involvement [13]. The researchers identified several barriers to accurately measuring patient preferences using the CPS, including heterogeneity in patient definitions of a “decision” and differences in the rationale for preferences.

Similarly, Entwistle et al. found discrepancies between interviews and survey data on decision-making preferences among women in the United Kingdom, and suggested that future research investigate the key features of “participation” in decision-making, as defined by patients [12]. Charles et al. have acknowledged the potential for different patient perceptions about SDM and have called for research exploring the sociocultural and illness contexts in which patients understand and experience shared decision-making [9].

This study sought to investigate how shared decision-making is conceptualized by African-American patients with diabetes. We were interested in understanding this population for several reasons. First, there is evidence that disparities in shared decision-making exist between African-Americans and whites [17–19]. Second, there are significant racial disparities in diabetes outcomes. African-Americans have worse diabetes control, more diabetes complications and higher diabetes-related mortality than whites [20–22]. Consequently, understanding and addressing inequities in shared decision-making among patients with diabetes has the potential to reduce diabetes-related health disparities. And finally, because individualized diabetes care requires ongoing treatment decisions, diabetes management and control may be particularly sensitive to patient/provider decision-making patterns.

The primary goal of this study was to develop a SDM model based on African-American diabetes patients’ conceptualization of SDM. Furthermore, to better understand the relationship between our model and the existing SDM literature, a second aim was to compare/contrast our findings with the primary elements presented in the Charles SDM model, which contains the following three key elements:

Information-sharing. This model emphasizes the importance of bidirectional information-sharing, where both patients (and their families) and physicians (and other health care personnel) actively discuss symptoms, diagnoses, lifestyle issues, and other issues important in choosing a treatment plan [9–11].

Deliberation. In the Charles model, patients and providers review the pros and cons of treatment options and discuss patient preferences. For patients with diabetes (and other chronic diseases), Charles et al. assign a greater weight to patient preferences, since patients have expertise in judging the feasibility of implementing treatments within the outpatient setting [11].

Decision-making. In this model, decision-making is a joint endeavor in which patients and physicians agree on a treatment plan. Decision-making is the essential domain in this model; without active patient participation in the selection of a treatment plan, SDM has not occurred. For patients with diabetes (and other chronic diseases), the SDM model was expanded to include a discussion about implementation, during which patient self-efficacy to perform self-management tasks is reviewed [9–11].

2. Methods

We conducted 24 in-depth, individual semi-structured interviews and 5 focus groups (n=27) among African-Americans with diabetes. Consistent with guidelines of qualitative methodology, data collection and analysis were conducted simultaneously, and enrollment continued until theoretical saturation was met [23]. Moderators/interviewers experienced in discussing health topics and interpersonal communication were matched to patients on race/ethnicity, because research has shown that racial/ethnic concordance in qualitative research fosters a “safe environment” that facilitates conversation, accurate data collection, and comprehension of cultural phenomena [24, 25]. Each focus group consisted of 5–6 people and lasted approximately 90 minutes. Individual interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes.

2.1 Patient recruitment

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), a letter was sent to attending physicians in an urban academic Internal Medicine (IM) practice explaining the study and requesting permission to contact their patients for study participation. All physicians in the practice gave consent. Study participants were recruited using purposeful sampling [26]. Eligible patients included African-Americans with diabetes, ages 21 years and older, who had an established relationship with an attending primary care physician (PCP) (defined as at least 3 visits over the preceding 2 years with the same attending). Potential study participants were identified through computer-generated lists created by searching administrative databases for patient visit information and codes for diabetes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) (250.00 – 250.91). Patients were randomly identified and up to three attempts were made to contact them via telephone. In addition, culturally-appropriate, low-literacy recruitment materials describing the study were posted in the clinic waiting room and examination rooms. Study participants received a $15 gift card to a local grocery store as an incentive.

2.2 Study Instruments

Topic guides (questions used to guide the interview in a semi-structured route) were created for the in-depth interviews and focus groups with the goal of exploring the following: patient definitions and perceptions of shared decision-making, barriers and facilitators of SDM, and the perceived impact of race/culture on SDM. The guides were created based on constructs of the Charles SDM model [9–11], the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [27] and the Ecological Model (EM) [28], pilot-tested, and modified in an iterative way. The Charles model was used to explore patient definitions and perceptions of SDM; the TPB and EM were used to explore patient willingness to engage in SDM, perceived SDM barriers/facilitators and the impact of race on SDM. According to the TPB, behavior is determined by a person’s intention to perform it, perceived control (self-efficacy) over performing the behavior, and the weighted relative importance of the behavioral attitudes and subjective norms [27]. The Ecological Model expands the influences on behavior to include environmental factors such as institutional influences (i.e. institutional racism) and social institutions [28].The EM and TPB models have been used previously to explore choice intentions, consumer behavior and health promoting behavior of African-Americans with diabetes [27–30]. Although several models were used to inform the development of the interview guide, our primary focus was to develop a conceptual framework based on patients’ conceptualization of SDM. Consequently, the overall investigation was guided by a grounded theory approach [23, 31].

The topic guide for the in-depth interviews began with a single-question instrument about patient preference for decision-making style: 1. “I prefer to leave all decisions regarding my treatment to my doctor” (passive) 2. “I prefer that my doctor and I share responsibility for deciding which treatment is best for me” (shared), or 3. “I prefer to make the final selection about which treatment I receive” (autonomous). Patients were then asked open-ended questions about “good” and “bad” decision-making experiences, which were followed with probes about SDM components, SDM barriers/facilitators and the impact of race on SDM. Patients were then asked questions based on the TPB and EM models (i.e. What things affect your ability to “speak up” with your doctor about health matters?). Each focus group began with an open discussion about patients’ definitions and perceptions of shared decision-making.

2.3 Data Analysis

Because we were interested in understanding how patients conceptualize SDM, we limited the analysis of in-depth interviews to those patients who stated a preference for shared decision-making, in response to the single-item instrument about preferences for decision-making style. Interview transcripts were excluded if participants reported preferring an autonomous or passive role.

Individual interviews and focus groups were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim and imported into Atlas.ti 4.2 software for coding. The in-depth interview transcripts were analyzed before the focus groups were undertaken. Five coders independently reviewed and coded the first transcript, and then met to discuss the coding, create uniform coding guidelines, and enhance inter-rater reliability. Subsequently, each transcript was independently coded by 2 randomly assigned reviewers who then met to resolve discrepancies. Outstanding issues were resolved by the entire group. A codebook was developed using an iterative process where modifications were made to the codes, themes, and concepts that arose from new transcripts [32]. After all in-depth interview transcripts were coded, they were divided equally among the five reviewers for in-depth review and analysis. Summaries of the final themes and concepts were discussed by the entire research group in an iterative manner. These themes formed the basis of the focus group topic guide. The focus groups were ultimately coded in a similar fashion (using the codebook) and analyzed for additional codes and themes.

The use of semi-structured, or in-depth, individual interviews afford a deep level of understanding of individuals’ experiences, beliefs, and values on a circumscribed range of issues [33]. Focus groups, on the other hand, afford social interactions that stimulate group members to confirm, refute, or expand on other group members’ reports [34]. Because focus groups allow exploration of interaction on a given topic and provide evidence for similarities and differences in participants’ opinions, our focus groups enabled the elicitation of broader cultural experiences [32]. Thus, our follow-up focus groups provided a validation ground for themes extracted and used (in the topic guide) from the individual data.

We then compared the dominant SDM domains that arose from our data to those from the Charles SDM model. To further compare differences between how SDM has been conceptualized by researchers and how it is understood by patients, we categorized each transcript (by participants who all had reported preferring a shared role) as passive, shared or autonomous based on the following assessment: Patients who reportedly followed their physician’s advice regardless of their stated personal preference were categorized as passive; patients who reportedly agreed/disagreed openly with physician advice and patients who reportedly decided to adhere/non-adhere to physician advice were categorized as having a shared role in decision-making because these patients relied on their personal preferences to make a decision about treatment plans; those patients who selected a treatment plan themselves from several physician-described options were classified as autonomous. A single coder (MP) reviewed and categorized each of the transcripts, and the categorical assignments were subsequently reviewed by the research team until consensus was reached.

3. Results

3.1 Sample

Of the 24 originally conducted in-depth individual interviews, 21 persons (88%) reported preferring a shared role with their physicians, based on the single-question instrument about decision-making preferences (3 reported preferring an autonomous role; no participants reported preferring a passive role). Transcripts from these 21 persons were retained for this study. There were 27 persons who participated in the focus groups, thus increasing our total sample size to 48 participants.

Patient characteristics

The majority of study participants were female (85%), three-quarters were unmarried, and approximately half were 40 to 65 years old (Table 1). Sixty percent of study participants had received “some college” or more education; nearly half the study participants were retired and half had private health insurance.

Table 1.

Patient demographics (n= 48)

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, yrs) | 62 |

| 18–39 | 4 |

| 40–65 | 56 |

| > 65 | 40 |

| Female gender | 85 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 26 |

| Married/Living as married | 26 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 48 |

| Education | |

| Some high school or less | 5 |

| High school graduate | 35 |

| Some college | 39 |

| College graduate or higher | 21 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 16 |

| Unemployed | 37 |

| Retired | 47 |

| Income, $ | |

| <15,000 | 23 |

| 15,000–24,999 | 16 |

| 25,000–49,999 | 23 |

| > 50,000 | 23 |

| Refused | 14 |

| Living space | |

| Rent | 51 |

| Own | 47 |

| Other | 2 |

| Insurance status | |

| Uninsured | 0 |

| Medicare | 4 |

| Medicaid | 19 |

| Medicare + Medicaid | 21 |

| Private Insurance | 29 |

| Medicare + Private | 27 |

Shared Decision-Making

All patients in this study reported wanting to be involved in the decision-making process about health issues and “have a say”. Many reported wanting an equal relationship with their physicians. Participants in both the in-depth interviews and focus groups consistently expressed opinions that indicated a preference for shared decision-making.

“I think that it should be a ‘fifty-fifty’ process … where both should decide. I think maybe he should tell me and I should explain to him why I should get the treatment I think I should get. So maybe it should be ‘fifty-fifty’.”

“You should be very much involved in the decisions that are made about your health care…You know the possibilities and the effects, in terms of what is suggested you should do versus what you would want to do according to your own principles and beliefs.”

“They may be the doctor, but it is your body and you know it better then they do. They are only going by what you are saying in the first place. I want to be totally involved.”

Despite the general consensus about preferences for shared roles, there was heterogeneity among the group. When the 21 in-depth interview transcripts were analyzed, they were categorized by the research team as having the following decision-making preferences: passive roles (52%), shared roles (33%), and autonomous roles (14%). Diversity in SDM role preferences were further confirmed in the focus groups.

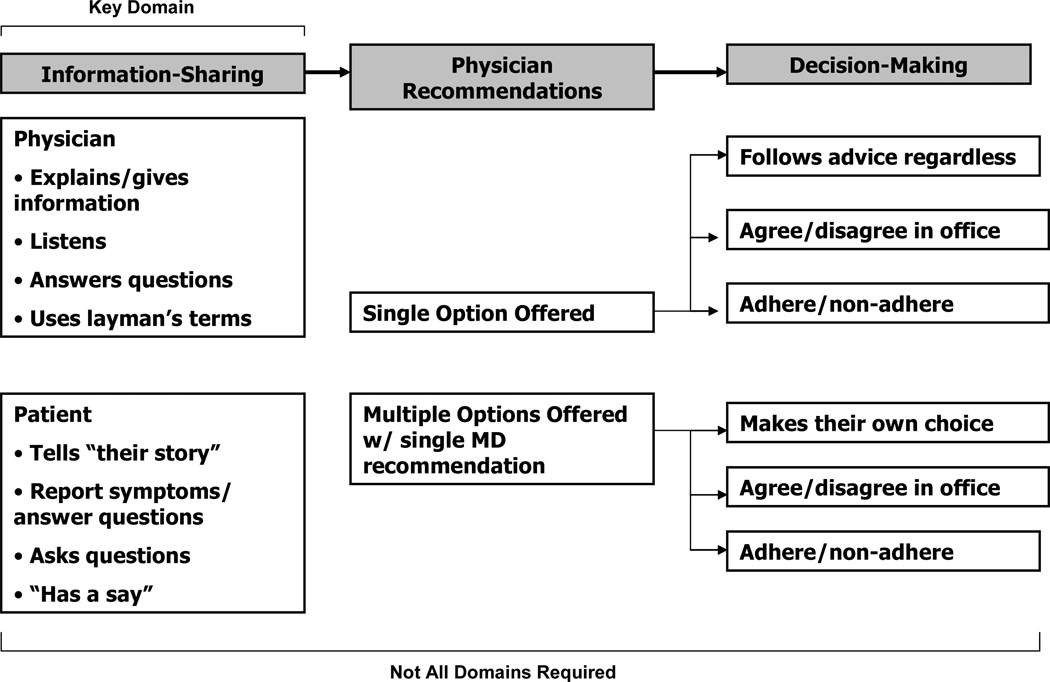

Three conceptual domains of shared decision-making were identified in this study: information-sharing, physician recommendations, and decision-making (Figure 2). Although the domains in our model were similar to the findings presented by Charles et al., we found important differences in how SDM was conceptualized by the African-American patients in our study.

Figure 2.

African-American Patient Model of Shared Decision Making

3.3.1 Information-Sharing

Information-sharing was the most frequently discussed domain among all participants, regardless of whether they were ultimately classified as passive, shared or autonomous.

“To me, [SDM] means two-way communication. You tell the doctor your problems, your story, and the doctor tells you what’s wrong. You’ve got to have both sides talking to one another. Sharing information.”

Many patients, particularly those categorized as passive, defined SDM exclusively on the existence of information-sharing. Consistent with the Charles model, our sample of African-American diabetes described information-sharing as a central SDM domain. Patients indicated that information-sharing is important for both physicians and patients. Physician information-sharing behaviors were primarily defined as those that facilitated clear, understandable communication “in layman’s terms” (Table 2, Section 1a).

Table 2.

African-American Patients’ Perceptions and Definitions of Shared Decision-Making (SDM) Domains

| 1a. Information-Sharing: Physician Actions | “He listened to me, and he’s taking in what you say, and he jumps right on it….he takes care of you…he understands how I feel…” (patient characterized as passive) “It isn’t that I don’t trust her, I just want her to listen to what I’m saying and act on it…” (patient characterized as passive) “She explained everything I needed to know about the situation…she explained them in layman’s terms…” (patient categorized as passive) “I would like to have a say…I think they should give me all the information when I ask, and they should tell me what’s wrong. And [when] I want to find out more about it, they should answer my questions.” (patient categorized as shared) “I liked the way she explained things to me and told me ‘why this’ and ‘why that’…you could talk to her about your problems or health or whatever and she would explain things to you…Both of us together make the decision and she lets me know what she thinks is best for me.” (patient categorized as shared) |

| 1b. Information-Sharing: Patient Actions | “I prefer that the doctor and I decide together… When he prescribes what he prescribes, I’m all for it. I want to have a say in things, but I go along with what he tells me.” (patient characterized as passive) “When the doctor [is] talking to you and explaining things, you are supposed to sit and listen and don’t interfere with the doctor…If there is something you want to know, ask the doctor and find out definitions of these different things.” (patient characterized as passive) “It kinda made me mad because I’m trying to tell them what my body can and cannot take. And I know some doctors tell you about your body, but I know my body better than anybody…” (patient characterized as shared) “There are doctors our there that will listen to you and tell you what’s going on right then and there, but then some doctors don’t know what they are doing…You are not going to know what’s wrong with me unless I tell you.” (patient characterized as shared) “God has given us this strength to speak up, to tell people what we think… the positives and the negatives. You just can’t sit here like a dummy and listen to [the doctor] say ‘Take this’ and ‘Take that.’ You have to question them…” (patient characterized as autonomous) |

| 2. Physician Recommendations | “No, we don’t talk about [my] needs or what I want. [The doctor] just tells me what he thinks I should do.” “I prefer that the doctor and I make decisions together … if the doctor gives me a recommendation and advice, I think I have choices. I think I should have choices…” “Is [the doctor] going to recommended one or the other or both of them? {moderator: She’s saying either one would be an acceptable choice.} See that what I’m saying…that it isn’t making any sense to me. Because you can either take one or the other, and if it’s suppose to be both of them then you take both of them, but if it’s not, then you take one or the other.” |

| 3a. Decision-Making: Passive patients | “She said that I should start taking insulin and diabetes pills (GOT LOUDER) that I don’t want to take anyway. And I try to do what is best for me but that’s it…. I am a praying person, loving the Lord, and I try to do what is best for [me]… I take all my medicines.” “We make decisions together and she gives me what I’m suppose to take and she knows what I’m suppose to take.” “I just take my medicine. She sends me through different things and whatever she prescribes I take…Everything seems to be all right so far… I haven’t had any problems.” |

| 3b. Decision-Making: Shared patients | “We sit in the office there and she tells me (laughs), she tells me what to do and if I don’t like it I’ll say ‘No I don’t want to do that.’ I’m 73 years old okay? Some things we just know we ain’t gonna do.” “She told me I need to go to the dermatologist … Now the lady up there at the check out desk- I told her that I didn’t want to go. That if this [skin growth] goes down, then I don’t see a reason to [operate]. So, I’ll have think about that… {moderator: Did you talk to your doctor about your preferences for one treatment or the other?} Well I didn’t tell [my doctor] about my preference for not messing with it … I just told her that I would go through with it. ” “See, when the doctor tells me what to do, then I can make up my mind whether or not to do [it].” |

| 3c. Decision-Making: Autonomous patients | “I want to have as much information [as possible], and I am interested in his recommendation. But I want to make the final decision.” “I want to talk to him and have him make a recommendation for what’s best for me but it’s my decision to decide whether I want to take this or not… I like that. I make the decision on whether I want to take it and he recommends saying I can either do this or do that, so if I have to have surgery or whatever let me be the one to call the shots.” |

Patients described information-sharing behaviors of patients as those that allowed them to “tell their story” (Table 2, Section 1b). More important than mere symptom reporting was the need to interact with physicians in such a way that patients’ experiences were “heard” and validated. Even the most passive patients, who were not able to describe an active role for themselves, wanted the sense of “having a say” with their provider.

3.3.2 Physician Recommendations

A second major SDM domain that emerged from our data is that of physician recommendations. Key to sharing in decision-making is a knowledge of, and physician recommendation for, treatment options.

“I prefer that my doctor and I share responsibility for deciding which treatment is best for me… I should know my choices and then along with my doctor, if I trust my doctor, then I think that she would give me good advice.”

Patients were interested in reviewing treatment options and often wanted to feel as though they “had choices”, even if they weren’t willing to actually choose among the available options. For some patients, having a doctor describe the options felt the same as having the doctor actually offer a range of options. In contrast to the Charles model, patients in our study did not describe deliberation over options or discussions about patient preferences. Rather, they described receiving final recommendations about treatment plans from their physicians (Table 2, Section 2).

However, a few patients were so unaccustomed to having more than one treatment plan described, that the concept of multiple, acceptable treatments was a new and confusing concept. There were a few patients who reported physician equipoise about treatment strategies, but these were usually accompanied by a single recommended treatment plan.

3.3.3. Decision-Making

Decision-making was the final major SDM domain that emerged from our data. Many participants considered the process of selecting, and acting upon, treatment options to be crucial to SDM.

“[SDM] is all about who gets to decide and how. See, it’s my body, so I want to decide what medicines I have to take every day. But the doctor, he knows more about the medicines, the side effects and all. So he wants to decide, too.”

Patients in this study described a process of decision-making wherein physicians would offer a treatment plan and patients would respond to the recommendation in one of several ways: following the recommendation regardless of the patient’s personal preferences, agreeing/disagreeing openly with the recommendation based on their personal preferences, or deciding to adhere or non-adhere to the recommendation once at home (Figure 2). Patients who described using adherence/non-adherence often noted that they would agree to the treatment plan in the doctor’s office, even if they were not sure about intentions to adhere to the plan. In those cases where multiple treatment options were presented to patients along with a recommendation, patients described responding by selecting their own treatment plan based on personal preferences, agreeing/disagreeing with the physician recommendation based on their personal preferences, or deciding to adhere or non-adhere to the recommendation once at home (Figure 2). This multi-pronged approach to decision-making provides a complex framework for understanding how decision-making actually occurs within clinical encounters, and helps us better define decision-making roles, based on patient definitions, for passive, shared and autonomous patients (Table 2, Sections 3a, 3b, and 3c). This domains contrasts with the Charles model, wherein physicians and patients mutually agree upon a treatment within the context of the clinical encounter.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that explores how shared decision-making is conceptualized by African-American patients. Our results suggest that African-American diabetes patients want to actively dialogue with their physicians, “have a say”, and share in the decision-making process. Nearly all patients reported preferring a shared role with their physician, and reported that the patient/provider relationship should be “fifty-fifty”.

Yet, patient perceptions of what it means to “share” in the decision-making process differed significantly from how shared decision-making has been conceptualized in the literature. Of the 21 patients who said they preferred a shared role with the single-question instrument, only one-third were categorized as such when their interviews were mapped onto domains of the Charles model. In the Charles model, the most widely utilized SDM conceptual model, bidirectional information-sharing, deliberation and decision-making are three domains that must all be present in order for shared decision-making to have occurred [9–11]. Moreover, the decision-making domain is seen as the most essential aspect of SDM.

Although patients described SDM domains that were generally consistent with the Charles model, key differences existed. First, many patients defined shared decision-making based on one domain or even a single element of a domain (i.e. the ability to “tell their story and be heard” by their physician). All domains of the Charles model were not necessary for most patients to have felt like meaningful sharing had occurred within the clinical encounter. In addition, information-sharing was the most salient SDM domain to patients in our study. Information-sharing was discussed more frequently than any other domain and was described most often as the defining element of shared decision-making. Our research suggests that information-sharing may be more important to African-American diabetes patients than helping to select a treatment plan. Such findings may not be limited to African-Americans, however. In a national survey of U.S. households, Levinson et al. found that patients had higher preference ratings for information-sharing than for decision-making [35]. Nonetheless, information-sharing may be particularly important to African-Americans, who typically have higher levels of provider mistrust and may place particular importance on relationship-building activities such as information-sharing [36, 37].

Although the Charles model has emphasized the importance of bidirectional information-sharing, physician behaviors (identifying the problem, explaining the disease process, presenting treatment options, discussing pros and cons of such options, making a recommendation, and clarifying patient understanding) have generally dominated the information-sharing domain in the literature [8]. While patients in our study wanted physician contributions during information-sharing (and stressed the importance of communicating in “layman’s terms”), they were also interested in patient contributions to the information-sharing process. Patients described the value of being able to “tell their story” and “be heard” by physicians. Having providers validate patient concerns and experiences was an important outcome of patient contributions to the information-sharing process.

Another important difference exists within the deliberation/physician recommendation domain. In the Charles model, there is a joint deliberation about treatment options, and preferences of the patient are discussed. In general, the patients in our study did not report such a deliberative process. This experience has been substantiated by Entwistle and colleagues, who videotaped physician consultations and found that few options were presented to patients during clinical encounters [14]. None of the patients in our study reported having their preferences sought by their physicians. If multiple treatment choices were described, patients felt like they had been offered, even if the physician ultimately proposed only one treatment plan.

Finally, patient descriptions of the decision-making domain differed from the Charles model. Rather than mutually agreeing upon a decision that results from co-deliberation, patients reported responding to physician recommendations either verbally (agreeing or refusing to follow the recommendation) or behaviorally (adhering or non-adhering to the recommendation). As such, “noncompliance” with treatment plans was often perceived by patients as an appropriate method for patients to express control and actively participate in treatment decisions. Moreover, such “decisions” about care often occurred at home, or in other circumstances outside of the clinical encounter, without the physician’s knowledge. This was particularly true of patients who felt too disempowered to verbally disagree with their physician and preferred more passive, non-confrontational expressions of their care preferences.

4.2 Conclusion

In summary, the vast majority of African-American diabetes patients in our study reported preferring a shared decision-making role with their providers, although this preference was primarily based on a SDM definition that emphasized information sharing rather than decision-making sharing. Because of such definitional differences, the patients in our study actually ranged from passive to autonomous, when categorized based on conceptual models by Charles et al. There were also significant differences in patient definitions of the decision-making domain, such that non-adherence to treatment plans was often viewed as a mechanism to exert patient control and act upon patient preferences for treatment, particularly among passive patients who wanted to avoid physician confrontation.

This study has several limitations. First, the study took place in an urban academic medical center within the midwest region of the United States; the majority of our patients were women and nearly half of patients were retired. As such, our findings may not be generalizable to all African-Americans with diabetes. Second, this research utilized a purposeful sample of patients. Consequently, patients who had particularly strong and/or negative communication experiences with their physicians may have been more likely to join the study. An important next step will be to conduct a cross-sectional study of diabetes patients to further explore SDM perceptions among a larger sample of African-Americans as well as other racial/ethnic groups.

Nonetheless, our study has several strengths. While it builds upon prior shared decision-making research, it focuses on a specific sociocultural and illness context, and in so doing, allows for a more meaningful understanding of how SDM can be operationalized among different populations. Second, our study also utilized a multi-method approach that enhanced our ability to accurately interpret our results.

4.3 Practice Implications

Our findings have important implications. First, current definitions and measures of SDM may not fully or accurately reflect patients’ understanding of what shared decision-making means to them, at least among African-Americans with diabetes. Consequently, emphasizing information-sharing, particularly that which empowers patients to “tell their stories” and have their experiences validated, may be more meaningful to such patients and strengthen the patient-provider relationship more so than efforts to engage patients in choosing a treatment plan. However, because most patients in our study had not experienced the joint deliberation and collaborative decision-making described in the literature, it will also be important to identify and address barriers to patient participation in these two domains before assuming that they are unimportant to African-Americans with diabetes. As such, developing culturally-tailored interventions that increase the self-efficacy of African-American patients in the SDM process is an essential area of future research. Similarly, it is important to find effective tools and strategies that assist busy practitioners in engaging this population in the decision-making process. These types of interventions have the potential to address patient and physician barriers to SDM among African-Americans with diabetes, and pave the way for all aspects of the Charles model to become more easily incorporated into clinical encounter. Finally, new instruments should be developed which can accurately measure patient preferences for decision-making roles within the sociocultural and illness contexts in which patients currently exist.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Diabetes Research and Training Center (DRTC) (P60 DK20595) and a DRTC Pilot and Feasibility Grant (P60 DK20595). Dr. Peek is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development program and the Mentored Patient-Oriented Career Development Award of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23 DK075006-01). Support for Dr. Chin is provided by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the NIDDK (K24 DK071933-01). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication. Dr. Peek had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

I confirm that all patient identifiers have been removed so the patients described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T, Wagner E, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;288:1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams RJ, Smith BJ, Ruffin RE. Impact of the physician’s participatory style in asthma outcomes and patient satisfaction. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86:263–271. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision-making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charles C, Gafini A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango) Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montori VM, Gafni M, Charles C. A shared treatment decision-making approach between patients with chronic conditions and their clinicians: the case of diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9:25–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Entwistle VA, Skea ZC, O’Donnell MT. Decisions about treatment: Interpretations of two measures of control by women having a hysterectomy. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:721–732. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davey HM, Lim J, Butow PN, Barratt AL, Redman S. Women’s preferences for and views on decision-making for diagnostic tests. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1699–1707. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Entwistle VA, Watt IS, Gilhooly K, Bugge C, Haites N, Walker AE. Assessing patients’ participation and quality of decision-making: insights from a study of routine practice in diverse settings. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Degner L, Sloan J. Decision making during serious illness: What role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley JG, Zia MJ, Hamilton N. Patient preferences for control in medical decision making: a scenario-based approach. Fam Med. 1996;28:496–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, Ford DE. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282:583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver MN, Goodwin MA, Gotler RS, Gregory PM, Stange KC. Time use in clinical encounters: are African-American patients treated differently? J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93:380–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. J Amer Med Assoc. 2001;286:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanting LC, Joung IM, Mackenbach JP, Lamberts SW, Bootsma AH. Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients: a review. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2280–2288. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter JS, Pugh JA, Monterrosa A. Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in minorities in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:221–232. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson RM, Barr PA, Edwards GJ, Funnell MM, et al. Using focus groups to identify psychological issues of urban black individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 1996;22:28–33. doi: 10.1177/014572179602200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson JS. Methodologic approach. In: Jackson JS, editor. Life in black America. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burnet D, Plaut A, Courtney R, Chin MH. A practical model for preventing type 2 diabetes in minority youth. Diabetes Educ. 2002;28:779–795. doi: 10.1177/014572170202800519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White KM, Terry DJ, Troup C, Rempel LA. Behavioral, normative and control beliefs underlying low-fat dietary and regular physical activity behaviors for adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:485–494. doi: 10.1080/13548500601089932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Britten N. Qualitative research: Qualitative interviews in medical research. Br Med J. 1995;311:251–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wackerbath SB, Streams ME, Smith MK. Capturing the insights of family caregivers: Survey item generation with a coupled interview/focus group process. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1141–1154. doi: 10.1177/104973202236582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making: A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1156–1163. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]