Abstract

GH receptor (GHR) mediates important somatogenic and metabolic effects of GH. A thorough understanding of GH action requires intimate knowledge of GHR activation mechanisms, as well as determinants of GH-induced receptor down-regulation. We previously demonstrated that a GHR mutant in which all intracellular tyrosine residues were changed to phenylalanine was defective in its ability to activate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)5 and deficient in GH-induced down-regulation, but able to allow GH-induced Janus family of tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2) activation. We now further characterize the signaling and trafficking characteristics of this receptor mutant. We find that the mutant receptor's extracellular domain conformation and its interaction with GH are indistinguishable from the wild-type receptor. Yet the mutant differs greatly from the wild-type in that GH-induced JAK2 activation is augmented and far more persistent in cells bearing the mutant receptor. Notably, unlike STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation, GH-induced STAT1 tyrosine phosphorylation is retained and augmented in mutant GHR-expressing cells. The defective receptor down-regulation and persistent JAK2 activation of the mutant receptor do not depend on the sustained presence of GH or on the cell's ability to carry out new protein synthesis. Mutant receptors that exhibit resistance to GH-induced down-regulation are enriched in the disulfide-linked form of the receptor, which reflects the receptor's activated conformation. Furthermore, acute GH-induced internalization, a proximal step in down-regulation, is markedly impaired in the mutant receptor compared to the wild-type receptor. These findings are discussed in the context of determinants and mechanisms of regulation of GHR down-regulation.

Growth hormone is a peptide hormone predominantly derived from the anterior pituitary that critically affects growth and metabolism by binding to cell surface GH receptor (GHR) on multiple target tissues (1–3). GHR has an approximately 246-residue glycosylated GH-binding extracellular domain, a single transmembrane domain, and an approximately 350-residue intracellular domain that binds the Janus family of tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2) and possesses conserved tyrosine residues that are phosphorylated by JAK2 upon GH-induced GHR activation (3). GH action is triggered by inducing conformational changes in cell surface GHR that render receptor dimers more able to foster JAK2 activation and promote activation of downstream STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription), including STAT5 and STAT1, and other signaling cascades (3–12). GH-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT allows their effective nuclear translocation and DNA sequence-specific regulation of genes important in GH actions (13–16).

Cell surface GHR availability is a key determinant of GH responsiveness. GH-independent factors that regulate GHR abundance and mechanisms that govern changes in GHR abundance (down-regulation) in response to GH are critical in overall regulation of GH sensitivity. Ligand-independent determinants of GHR cell surface abundance include factors that regulate receptor gene expression (17, 18) as well as those that govern receptor protein stability, such as JAK2's propensity to chaperone nascent receptor to the cell surface and there protect the mature receptor from constitutive endocytosis and degradation (19–23), and susceptibility of the surface receptor to inducible metalloproteolytic processing (24–27).

Surface GHR abundance is also modulated by GH binding and resultant receptor internalization and degradation. However, the degree to which GH augments constitutive receptor turnover and the role of GH-induced receptor tyrosine phosphorylation in promoting receptor turnover are points of controversy. Some investigators, mainly relying on methods that track the fate of the ligand, conclude that GH only minimally increases receptor internalization and degradation (28–30). However, we and others (22, 31) noted that GH-induced JAK2 activation markedly reduces surface receptor; in particular, we tracked the fate of immunologically detectable receptor and found that a catalytically-inactive JAK2, a JAK2 mutant incapable of associating with GHR, or a receptor mutant deficient in JAK2 binding rendered GH far less able to promote receptor downregulation compared with expression of wild-type receptor and JAK2 (22). Furthermore, although a receptor mutant with all intracellular tyrosine residues changed to phenylalanine allowed acute GH-induced JAK2 activation, this tyrosine phosphorylation-defective receptor underwent markedly less GH-induced ubiquitination and was only modestly down-regulated (22).

Herein, we compare further the signaling and trafficking characteristics of the wild-type GHR with those of the all tyrosine-to-phenylaline (YF) mutant. We find that GH-dependent receptor down-regulation, assessed under either persistent or transient GH exposure and under conditions in which new protein synthesis is prevented, is substantially diminished for the YF mutant. Additionally, GH-induced JAK2 and STAT1 signaling are markedly prolonged in cells expressing the YF mutant, suggesting that impaired GH-induced receptor down-regulation has functional signaling consequences. Furthermore, using a surface biotinylation method to compare acute GH-induced receptor internalization, we find the YF mutant defective in the most proximal stage of ligand-induced down-regulation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Recombinant human (h)GH was kindly provided by Eli Lilly & Co. (Indianapolis, IN). Phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) and routine reagents were from Sigma Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Zeocin was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). G418 and hygromycin were from Mediatech, Inc. (Manassas, VA). Fetal bovine serum, gentamicin sulfate, penicillin, and streptomycin were from BioFluids (Rockville, MD). Sulfosuccinimidyl 2 biotinamido ethyl 1,3 dithiopropionate (EZ-link) and neutravidin beads were from Pierce Chemical Co. (Rockford, IL).

Antibodies

Anti-p-JAK2 rabbit antibody reactive with JAK2 that is phosphorylated at residues Y1007 and Y1008 (reflective of JAK2 activation) was from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY). Polyclonal anti-phospho-STAT5 was from Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA). Anti-STAT5 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyclonal anti-phospho-STAT1 and anti-STAT1 were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Polyclonal anti-GHRcyt-AL47 against the intracellular domain of GHR (32) and anti-JAK2AL33 (33) were previously. Anti-GHRext-mAb, reactive with the GHR extracellular domain, has been previously described (34, 35).

Cells and cell culture

γ2A-pGHR-JAK2 (referred to as “GHR cells”) and γ2A-MYFc8-JAK2 (referred to as “MYFc8 cells”) have been described elsewhere (22). Briefly, these are stable transfectants in which the wild-type porcine GHR or a porcine GHR mutant with each of its eight intracellular tyrosine residues are changed to phenylalanine (MYFc8) are coexpressed with murine JAK2 in the GHR- and JAK2-deficient γ2A human fibrosarcoma cell line. These stable cell lines were maintained in DMEM (1 g/liter glucose) (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 200 μg/ml G418, 100 μg/ml hygromycin B, and 100 μg/ml Zeocin.

Cell starvation, cell stimulation, protein extraction, electrophoresis, and immunoblotting

Serum starvation of cells was accomplished by substituting 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA (fraction V, Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) for serum in culture media for 16–20 h before experiments. Adherent cells were stimulated with hGH (indicated concentrations and duration) in DMEM (low glucose) with 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA at 37 C. For PMA treatment, previous protocols were followed (25). Stimulations were terminated by washing cells once with ice-cold PBS in the presence of 0.4 mm sodium orthovanadate (PBS-vanadate). Cells were harvested by scraping in ice-cold PBS-vanadate, and pelleted cells were collected by brief centrifugation. For protein extraction, pelleted cells were solubilized for 30 min at 4 C in lysis buffer (1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaF, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 10 mm benzamidine, 10 μg/ml aprotinin). After centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4 C, detergent extracts were electrophoresed under nonreducing or reducing conditions, as indicated. Resolution of proteins by SDS-PAGE, Western transfer, and blocking of Hybond-ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) with 2% BSA were performed as described elsewhere (19, 25, 34–37). Immunoblotting with anti-GHRcyt-AL47 (1:4000), anti-JAK2AL33 (1:4000), anti-STAT5 (1:1000), anti-p-JAK2 (1:1000), anti-STAT1 (1:1000), anti-p-STAT1 (1:1000), or anti-p-STAT5 (1:1000) with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit secondary antibodies (1:10000) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate; all from Pierce Chemical Co.), and stripping and reprobing were according to the manufacturer's suggestions.

Cell surface biotinylation and internalization assay

Cell surface biotinylation and the GHR internalization assay were carried out as described elsewhere (38, 39). Serum-starved GHR or MYFc8 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and incubated with 0.375 mg/ml EZ-Link-Sulfo-NHS-S-S-biotin or vehicle for 30 min at 4C. After removal of biotin, cells were either kept on ice (time point 0 min) or incubated at 37C with 500 ng/ml of GH for 2 min, 7 min or 15 min. After removal of surface-bound biotin by incubation with the reducing reagent sodium 2 mecaptoethanesulfonate and quenching of residual sodium 2 mecaptoethanesulfonate with iodoacetamide, cells were lysed. Biotinylated proteins in the lysate were recovered on immobilized NeutrAvidin (Pierce Chemical Co.) overnight, washed, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GHRcyt-AL47.

Results and Discussion

Mutation of GHR intracellular tyrosine residues alters the kinetics of GH signaling

Six tyrosine residues within the GHR intracellular domain are conserved across many species. Studies that either directly or indirectly assessed rat and porcine GHR tyrosine phosphorylation suggest that each of the conserved tyrosines may be phosphorylated in response to GH (40–44). Human GHR mutagenesis suggests that three of these tyrosine residues are critical, but redundant, for GH-induced STAT5 activation (45). To further study how intracellular domain tyrosine phosphorylation affects GH-induced signaling and receptor trafficking, we compared the wild-type porcine GHR to a porcine GHR in which all eight intracellular domain tyrosine residues are mutated to phenylalanine (MYFc8) (42). Expression vectors containing cDNA for each receptor were stably expressed, along with JAK2, in the GHR- and JAK2-deficient human fibrosarcoma cell, γ2A. The resulting cell lines [γ2A-pGHR-JAK2 (referred to as “GHR cells”) and γ2A-MYFc8-JAK2 (referred to as “MYFc8 cells”)] have been described elsewhere (22). The response of GHR and MYFc8 cells to acute stimulation with GH is shown in Fig. 1, A and B. As previously observed, treatment with GH for 15 min promoted robust JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation in both cells, approximately 2-fold greater in MYFc8 cells than in GHR cells. However, GH failed to cause STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation in MYFc8 cells, consistent with the requirement for GHR tyrosine phosphorylation for optimal STAT5 activation (46).

Fig. 1.

Altered kinetics of GH signaling in MYFc8 cells vs. GHR cells. A and B, Acute GH-induced JAK2 and STAT5 signaling. A, Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle or GH (500 ng/ml; 15 min). Detergent extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE and sequentially immunoblotted to detect phosphorylated and total JAK2 and phosphorylated and total STAT5. The figure shown is representative of six such experiments. B, Experiments (n = 6) such as those shown in panel A, but with 250 ng/ml GH, were analyzed denstiometrically. In each case, P-JAK2 signal was normalized for JAK2 signal and expressed as the normalized GH-induced JAK2 activation in MYFc8 cells relative to that in GHR cells. *, P < 0.05 between conditions. C and D, GH signaling time course. C, Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle for 60 min (left panel) or 5 h (right panel) or with GH (250 ng/ml) for the indicated durations before detergent extraction, SDS-PAGE, and sequential immunoblotting, as indicated. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments. D, Experiments (n = 4) such as those shown in panel C were performed for MYFc8 cells and analyzed densitometrically as in panel B. Normalized GH-induced JAK2 activation is expressed at each GH time point relative to the normalized signal obtained after 1 h of GH exposure. E, GH pulse and washout. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle (−) or GH (250 ng/ml) for 15 min, after which the GH was washed out and cells were incubated thereafter for 0, 15, 30, or 60 min, as indicated. Cells were then detergent extracted, and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by sequential immunoblotting, as indicated. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments.

We further evaluated signaling responses in short (0–60 min) and long (0–5 h) time course experiments exemplified by that shown in Fig. 1C. GH-induced JAK2 and STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation in GHR cells was rapid and transient, with both evident as soon as 5 min after GH exposure. As expected, JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation peaked before STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation, but both were largely dissipated after 1 h of GH exposure. In contrast, GH-induced JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation in MYFc8 cells was both rapid and remarkably sustained, persisting at high levels over the 5 h of continuous GH exposure (quantitatively displayed in Fig. 1D). Despite this, no GH-induced STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation was detected in MYFc8 cells at any point. We tracked GHR levels in both cells by immunoblotting with antiserum against the receptor intracellular domain. In GHR cells, mature wild-type receptor abundance decreased rapidly after as little as 15 min GH exposure and was nearly undetectable after 2 h of GH. In contrast (and similar to our previous findings), continuous GH exposure promoted modest loss of MYFc8 GHR in the MYFc8 cells before 2 h (more below). Thus, prolonged GH-induced JAK2 activation in MYFc8 cells is correlated to the relatively reduced GH-induced receptor down-regulation.

Reasoning that physiological GH exposure is generally more pulsatile than continuous, we explored whether the same findings ensued if GH exposure was more transient (Fig. 1E). GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle (−) or GH (+) for 15 min, after which the stimuli were removed by washout and refeeding of the cells with fresh buffer without GH for 0–60 min. As in Fig. 1, A–C, acute GH exposure for 15 min promoted enhanced JAK2 activation in MYFc8 cells compared with GHR cells. With GH washout, JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation rapidly dissipated in GHR cells. Similarly, acute STAT5 activation decreased progressively with incubation in fresh medium after washout in GHR cells and was not detected in MYFc8 cells. Notably, the sustained JAK2 activation seen with continuous GH exposure in MYFc8 cells was also observed, even 60 min after washout of the stimulatory GH pulse.

The stimulation/washout paradigm has been used to study the kinetics of deactivation of GH-induced JAK2/STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation (47–49). Those studies suggested that the process of deactivation of GH signaling is initiated by the GH pulse and continues after hormone withdrawal, much as we currently observe in GHR cells. Although deactivation may be mediated by phosphotyrosine phosphatase activity, it is less clear whether tyrosine phosphorylation of GHR itself is required for this deactivation (47); it is possible that both modulation (down-regulation) of GHR as well as postreceptor events may be necessary. In MYFc8 cells, GHR itself is not tyrosine phosphorylated, and deactivation of JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation is markedly impaired. We note that in the pulse-washout experiment in Fig. 1E, GH pulse-induced receptor down-regulation was substantial in GHR cells during the washout, but receptor down-regulation during the same phase was minimal in MYFc8 cells, mimicking findings obtained with continuous GH exposure in Fig. 1C. Thus, lack of GHR down-regulation per se may contribute substantially to the sustained JAK2 activation in MYFc8 cells.

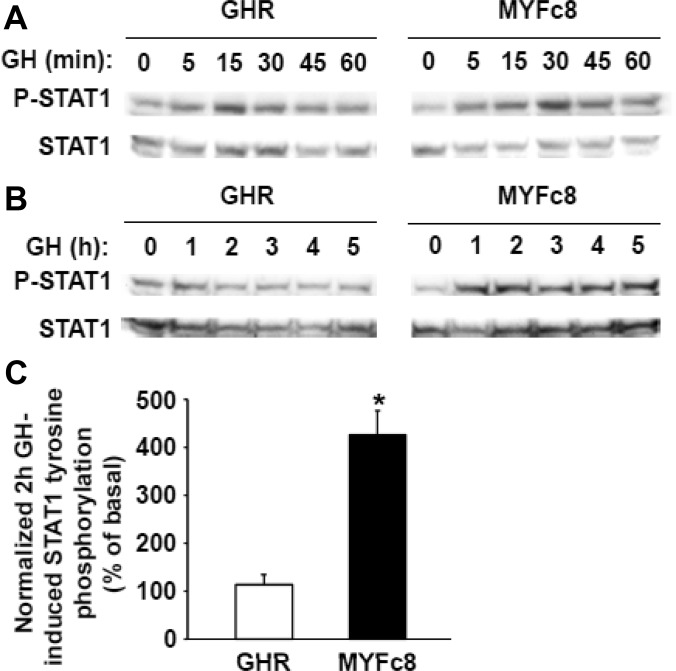

We also explored whether signaling downstream of JAK2 might also be sustained in MYFc8 cells. Because GH-induced STAT5 signaling is absent in those cells, we assessed GH-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1, which does not rely on GHR tyrosine phosphorylation (46) (Fig. 2). STAT1 was basally tyrosine phosphorylation in both GHR and MYFc8 cells. In GHR cells, GH transiently enhanced STAT1 tyrosine phosphorylation, peaking within 1 h (Fig. 2A, left panel). In contrast, markedly sustained GH-induced STAT1 tyrosine phosphorylation was observed in MYFc8 cells (Fig. 2B; quantitated in Fig. 2C), suggesting that sustained JAK2 activation exerted downstream signaling effects in those cells.

Fig. 2.

GH-induced STAT1 tyrosine phosphorylation in MYFc8 cells vs. GHR cells. A and B, Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle for 60 min (A) or 5 h (B) or with GH (250 ng/ml) for the indicated durations before detergent extraction, SDS-PAGE, and sequential immunoblotting, as indicated. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments. C, Experiments (n = 3) such as that shown in panel B, were analyzed denstiometrically. In each case, GH treatment for 2 h was compared with control treatment. P-JAK2 signal was normalized for JAK2 signal and expressed as the normalized GH-induced JAK2 activation in MYFc8 cells relative to that in GHR cells. *, P < 0.05 between conditions.

Mutation of GHR intracellular tyrosine residues does not affect GH-induced receptor disulfide linkage or PMA-induced receptor proteolysis

As degradation of the acutely GH-engaged receptor differed in GHR vs. MYFc8 cells even after GH washout, we further examined whether wild-type GHR and the MYFc8 GHR differed discernibly in terms of their ligand-binding extracellular domains. We took advantage of several assays that functionally probe extracellular domain conformation and response to GH.

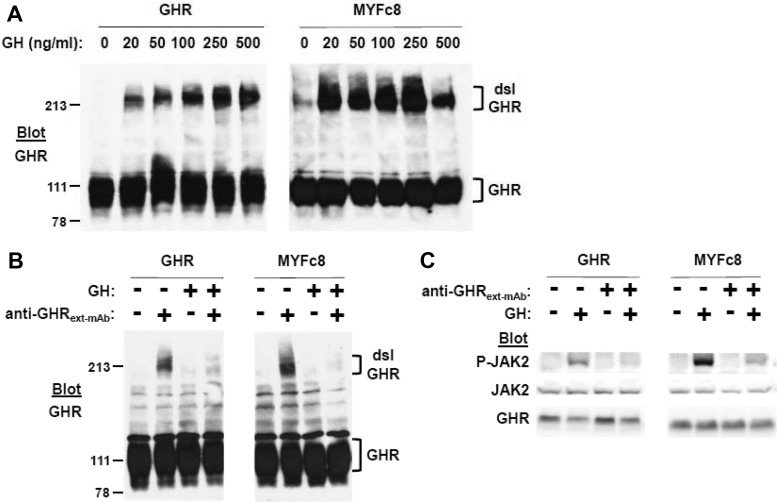

GHR extracellular domain contains seven conserved cysteine residues, six of which form three pairs of intrachain disulfide linkages; the remaining unpaired cysteine (cysteine-241 in human and rabbit GHR) is in the perimembranous stem region, several residues outside of the transmembrane domain (50, 51). We demonstrated in several cell types expressing either endogenous or transfected mouse, human, or rabbit GHR that GH promotes appearance of a disulfide-linked receptor form detectable by immunoblotting of cellular proteins resolved by nonreducing SDS-PAGE (21, 32, 34–36, 52). GH-induced GHR disulfide linkage is mediated by the unpaired cysteine (cysteine-241 or its equivalent) and biochemically reflects the acute GH-induced conformational changes associated with receptor activation (34, 36). We compared GHR and MYFc8 cells with regard to GH-induced receptor disulfide linkage (Fig. 3A). After acute exposure of cells to varying concentrations of GH, detergent lysates were resolved by nonreducing SDS-PAGE, and GHR were detected by immunoblotting. As for other species, porcine GHR (both wild-type GHR and MYFc8) underwent acute GH-induced disulfide linkage over a range of GH concentrations. Thus, mutation of all intracellular tyrosine residues did not alter the receptor's ability to undergo GH-induced conformational changes that approximate the unpaired cysteines in the stem region between GHR dimer partners.

Fig. 3.

GH-induced GHR disulfide linkage and anti-GHRext-mAb inhibition in MYFc8 cells vs. GHR cells. A, Acute GH-induced GHR disulfide linkage. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with GH (0–500 ng/ml, as indicated) for 15 min, before detergent extraction, SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, and anti-GHR immunoblotting. Positions of the disulfide-linked (dsl) and non-disulfide-linked GHR are indicated by brackets. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments. B, Anti-GHRext-mAb inhibition of GH-induced GHR disulfide linkage. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were pretreated with vehicle or anti-GHRext-mAb (18 μg/ml) for 10 min before treatment with vehicle or GH (500 ng/ml) for 15 min. Cells were then detergent extracted and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, followed by anti-GHR immunoblotting. Positions of the disulfide-linked (dsl) and non-disulfide-linked GHR are indicated by brackets. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments. C, Anti-GHRext-mAb inhibition of GH signaling. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were pretreated with vehicle or anti-GHRext-mAb (18 μg/ml) for 10 min before treatment with vehicle or GH (500 ng/ml) for 15 min. Cells were then detergent extracted, and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by sequential immunoblotting, as indicated. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments.

We previously reported preparation and characterization of a monoclonal antibody against the extracellular domain of the rabbit GHR (34–36). Anti-GHRext-mAb reacts with extracellular subdomain 2 that includes the interface between dimeric receptors in the GH-engaged assemblage and is a conformation-sensitive antibody; it can immunoprecipitate unliganded, but not GH-engaged, GHR (34, 36). Furthermore, pretreatment of cells bearing human or rabbit GHR with anti-GHRext-mAb prevents GH-induced receptor disulfide linkage and signaling by preventing GH-induced acquisition of the activated receptor conformation (34, 35). We tested the ability of anti-GHRext-mAb pretreatment to inhibit acute GH-induced GHR disulfide linkage (Fig. 3B) and GH-induced signaling (Fig. 3C) in GHR and MYFc8 cells. In GHR cells, GH-induced receptor disulfide linkage and JAK2 activation were dramatically inhibited by anti-GHRext-mAb pretreatment, indicating the antibody reacts with pig GHR in addition to rabbit and human GHR. Notably, the same pattern of inhibition was observed in MYFc8 cells. Thus, mutation of the intracellular tyrosine residues did not affect extracellular domain interaction with anti-GHRext-mAb or the antibody's inhibitory actions.

The third approach to probe the extracellular domain conformation of wild-type GHR vs. MYFc8 GHR was to compare susceptibility to inducible proteolysis. GHR of various species (mouse, rabbit, and human) are acutely cleaved in the perimembranous extracellular domain stem in response to protein kinase C activators and growth factors by the transmembrane metalloprotease TNF-α converting enzyme (ADAM-17) (24–27, 34, 53). This results in rapid loss of full-length GHR and transient accumulation of a receptor fragment (remnant) including remaining stem region amino acids, the transmembrane domain, and the intracellular domain. Interestingly, although cleavage occurs in the receptor extracellular domain, alteration of the transmembrane domain inhibits cleavability, despite permitting normal cell surface accumulation and GH-induced signaling (53). Likewise, JAK2, which binds to GHR's intracellular domain, enhances inducible receptor metalloproteolysis (26). Hence, the transmembrane and intracellular domains may influence sensitivity of the extracellular domain to proteolysis, presumably by subtly altering its conformation at or near the cleavage site. GHR cells and MYFc8 cells were treated with PMA for 0–30 min and extracted proteins were immunoblotted with anti-GHRcyt-AL47 to detect both full-length GHR and remnant (Fig. 4). PMA induced loss of GHR and accumulation of the remnant in both cells with very similar time courses. We conclude that intracellular domain changes resulting from mutation of the tyrosines did not affect the cell surface receptor's sensitivity to extracellular domain proteolysis by TNF-α converting enzyme.

Fig. 4.

PMA-induced GHR proteolysis in MYFc8 cells vs. GHR cells. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with PMA (0.1 μg/ml) for 0–30 min. Cells were then detergent extracted, and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by anti-GHR immunoblotting. The positions of GHR and the GHR remnant are indicated by brackets. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments.

Mutation of GHR intracellular tyrosine residues potentiates the survival of the GH-induced activated form of the receptor

The data in Figs. 1–4 collectively indicate that mutation of intracellular domain tyrosine residues renders the GHR deficient in allowing GH-induced STAT5 activation but augments the duration of GH-induced JAK2 and STAT1 activation. These dramatic changes in GH signaling are not associated with altered conformation of the receptor extracellular domain either absent of GH or in response to GH engagement. However, the pace of loss of the receptor itself differed for wild-type GHR vs. MYFc8 GHR cells treated with a high concentration of GH; the degree of GHR loss was approximately 2-fold greater in GHR cells compared with MYFc8 cells after 2 h of GH exposure (Fig. 1C; graphed in Fig. 5A). This aspect of GH responsiveness was further studied. We first examined effects on GHR abundance of prolonged (1.5 h) stimulation over a range (20–500 ng/ml) of GH concentrations in GHR vs. MYFc8 cells (Fig. 5B) to determine whether the differential effect was also observed at lower concentrations. Notably, treatment with as little as 20 ng/ml GH for 1.5 h markedly reduced steady-state GHR abundance in GHR cells, but not in MYFc8 cells. These results are in concert with observations in Fig. 1C and Ref. 22 that mutation of the intracellular tyrosine residues likely alters the fate of the GH-stimulated GHR, but differ from the recent conclusions of Putters et al. (30). Those authors compared cells stably expressing a wild-type GHR vs. a GHR with all intracellular tyrosines mutated (Fig. 6, C and D in that paper). It was interpreted that GH-induced (500 ng/ml for 1.5 h continuously; n = 2) GHR loss was similar for wild type and mutant. No other analysis (time course, concentration dependence) was reported. We cannot reconcile fundamental differences between our studies and those of Putters et al.; however, as noted by those authors, their stable transfectants differed considerably in terms of JAK2 abundance, whereas JAK2 levels in our GHR cells and MYFc8 cells were quite similar.

Fig. 5.

GH-induced GHR down-regulation and effects of CHX in MYFc8 cells vs. GHR cells. A, GH-induced GHR down-regulation. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with GH (250 ng/ml) for 2 h, before detergent extraction, SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting for GHR, as in Fig. 2C, above. GHR abundance after GH stimulation was normalized for abundance in control-treated cells for each cell type (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 between conditions. B, GH-induced GHR receptor down-regulation concentration dependance. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with GH (0–500 ng/ml, as indicated) for 1.5 h, before detergent extraction, SDS-PAGE, and sequential immunoblotting, as indicated. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of three such experiments. C–F, Effects of CHX treatment. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with CHX (20 μg/ml) for either 60 min or 5 h, as indicated, and with GH (250 ng/ml) for the indicated durations, before detergent extraction, SDS-PAGE (under nonreducing conditions in panel F), and immunoblotting with anti-GHR (panels C and F) or sequentially as indicated (panel E). Note that blots in the left and right panels of C and F were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figures shown are representative of three such experiments in each of panels C, E, and F. In panel D, relative abundance of GHR in GHR vs. MYFc8 cells treated with GH for 2 h compared with control treatment were densitometrically analyzed (n = 3), as in panel A above. *, P < 0.05 between conditions.

Fig. 6.

Surface biotinylation and GHR internalization assay in MYFc8 cells vs. GHR cells. A, Surface biotinylation. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle or biotin coupler, as in Materials and Methods. Cells were detergent extracted, and aliquots were precipitated with avidin beads and eluted or not precipitated before SDS-PAGE and anti-GHR immunoblotting. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. The figure shown is representative of two such experiments. B, Surface biotinylation does not affect GH-induced signaling. Serum-starved GHR cells and MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle or biotin coupler, as in Materials and Methods, before stimulation with vehicle or GH (500 ng/ml; 15 min). Cells were detergent extracted, and extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE and sequentially immunoblotted, as indicated. Note that blots in the left and right panels were actually contiguous (run on the same gel), but are separated for ease of visualization; exposures are thus processed identically and are comparable in the left and right panels. C, Internalization assay. Serum-starved GHR and MYFc8 cells were subjected to surface biotinylation and the internalization assay, as in Materials and Methods. GHR internalization (expressed as the % of total mature GHR detected by blotting) is plotted. (n = 4) *, P < 0.05 for GHR cells vs. MYFc8 cells at the indicated time point.

To better understand the differential effect of GH on receptor abundance in GHR cells vs. MYFc8 cells, we assessed receptor levels under conditions in which new protein synthesis was inhibited (Fig. 5C). This allowed us to better track by immunoblotting the fate of existing receptors without concern for potential effects of GH signaling on production of newly expressed receptors. GHR and MYFc8 cells were treated with GH for 0–60 min in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX) for 60 min (left panel) or with GH for 0–5 h in the presence of CHX for 5 h (right panel). Not surprisingly, both wild-type and MYFc8 GHR levels were less after 5 h of CHX compared with 60 min of CHX. However, with both CHX treatment regimens, GH-induced receptor loss was more rapid and of greater degree (∼1.9-fold greater loss in response to GH treatment for 2 h; Fig. 5D) for wild-type GHR than for MYFc8 GHR. These results are quite similar to those obtained in the absence of CHX (Fig. 5A) and suggest that the half-life of wild-type GHR was greatly lessened by GH treatment in comparison to the effect of GH on the half-life of MYFc8 GHR. We verified that CHX treatment did not alter the differences in signaling kinetics between GHR and MYFc8 cells observed in Fig. 1C. GH induced more transient JAK2 activation in GHR cells, but sustained JAK2 activation in MYFc8 cells (Fig. 5E). Thus, neither the prolonged activation of JAK2 nor the relative lack of receptor down-regulation we observed in MYFc8 cells depends on ongoing protein synthesis.

We also examined GH-induced GHR disulfide linkage in the presence of CHX (Fig. 5F). As expected, acute GH-induced receptor disulfide linkage was similar in GHR cells and MYFc8 cells in the presence of CHX (left panel). However, longer GH treatment in the presence of CHX (right panel) revealed that relative stabilization of MYFc8 GHR was most evident in the disulfide-linked receptor form. These data suggest that the activated form of the MYFc8 GHR induced by GH is particularly refractory to down-regulation and may be in such a conformation that it supports persistent activation or lack of deactivation of JAK2.

Mutation of GHR intracellular tyrosine residues reduces GH-induced internalization of the cell surface receptor

In principle, impairment of GH-induced down-regulation of the cell surface MYFc8 GHR compared with wild-type GHR might reside at any step in the down-regulation process, ranging from ligand-mediated endocytosis to postendocytic sorting to degradative organelles to resistance to degradation after entering the degradative compartment. GH-induced receptor ubiquitination was markedly reduced for the MYFc8 GHR compared with wild-type GHR (22). However, whether receptor ubiquitination per se is involved in GH-dependent down-regulation is unclear. Some workers (28, 54) have concluded that GH-induced ubiquitination of the GHR is not itself involved in down-regulation; others (55) suggest that GH-induced receptor down-regulation is intimately related to the function of GH-activated ubiquitin ligase action. Likewise, involvement of protein tyrosine phosphatases, some of which may interact with the tyrosine-phosphorylated GHR intracellular domain, in regulating the fate of the GH-engaged GHR (vs. the actions of GHR-associated tyrosine kinase) is unclear (44, 56).

Studies addressing GH-induced GHR internalization have often employed techniques that actually track the fate of the ligand (e.g. radiolabeled, fluorescent, or biotinylated versions of GH) as a proxy for the fate of the receptor. We asked whether GH-induced internalization of surface receptors differs for wild-type GHR vs. MYFc8 GHR by directly tracking the fate of the receptor, rather than the ligand. For this, we performed cell surface biotinylation (38) followed by assaying the degree of internalization of biotinylated GHR (39). This method employs biotin labeling of cell surface proteins at lysine residues under cold conditions via a thiol-sensitive coupling reagent, stimulation with GH at 37 C for varying duration, removal of remaining surface biotin by treating cells with a reducing agent, and assessment of internalized biotinylated GHR by precipitation of cell lysates with NeutrAvidin beads, SDS-PAGE, and anti-GHR immunoblotting of bead eluates (Fig. 6). We first verified that both wild-type GHR and MYFc8 GHR could be surface biotinylated and specifically recognized by avidin beads (Fig. 6). GHR cells or MYFc8 cells were treated with vehicle (−) or biotin coupler (+). Detergent extracts were either subjected to pull down by avidin beads and resolved by SDS-PAGE or resolved without precipitation by SDS-PAGE. Anti-GHR immunoblotting revealed that only biotinylated wild-type GHR and MYFc8 GHR were pulled down by the avidin beads, indicating the specificity of the process. We also verified that surface biotinylation did not alter GH's ability to bind and productively engage receptors (Fig. 6B). GH acutely promoted similar degrees of JAK2 and STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation within GHR cells or MYFc8 cells whether or not they were previously subjected to surface biotinylation.

Thus, surface biotinylation allowed specific detection of surface labeled GHR, but did not impair GH-GHR engagement. These are critical factors that allow us to track GH-induced internalization of surface GHR. As analyzed in several separate experiments (Fig. 6C), GH treatment of GHR cells produced the expected acute internalization of wild-type GHR over a period of 15 min. By comparison, GH-induced internalization of the MYFc8 mutant receptor, however, was markedly diminished. We emphasize that this type of experiment tracks the fate of GHR that were biotinylated at the cell surface rather than the fate of the ligand. Thus, potential alterations in the ligand dissociation characteristics or other ligand-specific trafficking issues between the GHR cells and MYFc8 cells could not affect our interpretation as they might if we tracked the fate of the ligand instead.

Although these data suggest that internalization from the cell surface of MYFc8 GHR in response to GH is markedly impaired compared with wild-type GHR, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that differences in internalization we detect are explained rather by altered (enhanced) recycling of internalized MYFc8 GHR vs. wild-type GHR. However, the acute time course employed makes this a very unlikely explanation of the findings. Rather, we favor the conclusion that MYFc8 GHR, likely because it cannot undergo tyrosine phosphorylation in response to GH, fails to engage internalization machinery at or near the cell surface and thus is deficient in the most proximal step of ligand-induced down-regulation. Future studies aimed at identification of the critical protein component(s) of the internalization machinery responsible for initiating normal GH-induced GHR down-regulation and isolation of specific receptor tyrosine residues required will be worthwhile. As a consequence of its defective internalization/down-regulation, we envision that MYFc8 GHR remains in a GH-induced activated conformation that potentiates prolonged activation of its associated tyrosine kinase, JAK2. Whether persistent JAK2 activation is contributed to by lack of recruitment of a regulatory protein tyrosine phosphatase to the vicinity of the receptor because of a lack of phosphorylated tyrosine-docking sites in the MYFc8 receptor intracellular domain is as yet unknown, but is also conceivable and worthy of further study.

Conclusions

We further characterized a GHR in which all intracellular tyrosine residues are replaced by phenylalanine. We previously found that GH caused no tyrosine phosphorylation of this mutant receptor or of STAT5, but allowed acute JAK2 activation, and that the mutant receptor was resistant to GH-induced down-regulation. Herein, we demonstrate that GH-induced JAK2 activation and STAT1 tyrosine phosphorylation are augmented and remarkably persistent in cells that express the mutant GHR compared with wild-type receptor-expressing cells. However, the mutant receptor undergoes normal acute disulfide linkage, is similarly susceptible as wild-type GHR to inhibition of GH signaling by a conformation-specific GHR antibody, and is equally sensitive as the wild-type receptor to inducible metalloproteolysis in the extracellular domain stem. Thus, mutation of the intracellular domain tyrosine residues does not affect the conformation of the extracellular domain or how it interacts with its ligand. We found that both resistance to down-regulation and persistence in JAK2 activation did not depend on continued protein synthesis or the sustained presence of GH. Moreover, the long-lived mutant GHR were enriched in the disulfide-linked form, which reflects the activated receptor conformation. By assaying internalization of cell surface receptors, we determined that the mutant receptor is deficient in GH-induced internalization, the most proximal step in its down-regulation. These data provide a framework for understanding the role of ligand-mediated internalization in regulating GH signal strength and quality.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate helpful conversations with Drs. X. Wang, Y. Zhang, Y. Huang, N. Yang, L. Liu, Y. Gan, D. Sun, P. Berry, K. Loesch, J. Xu, J. Messina, and X. Li (University of Alabama, Birmingham), Dr. S. Fuchs (University of Pennsylvania), and Dr. J. Kopchick (Ohio University) for provision of wild-type- and MYFc8-encoding plasmids.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK58259 (to S.J.F.) and a Veterans Affairs Merit Review award (to S.J.F.).

Parts of this work were presented at the 93rd Annual Endocrine Society Meeting in Boston, MA in 2011.

Disclosure Summary: L.D., J.J., and S.J.F. have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- CHX

- Cycloheximide

- GHR

- GH receptor

- JAK2

- Janus family of tyrosine kinase 2

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- YF mutant

- all tyrosine-to-phenylaline mutant.

References

- 1. Kaplan S. 1999. Hormonal regulation of growth and metabolic effects of growth hormone. In: Kostyo JL, Goodman HM, eds. Handbook of physiology. Chap 5 New York: Oxford University Press; 129–143 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Møller N, Jørgensen JO. 2009. Effects of growth hormone on glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism in human subjects. Endocr Rev 30:152–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carter-Su C, Schwartz J, Smit LS. 1996. Molecular mechanism of growth hormone action. Annu Rev Physiol 58:187–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frank SJ, Gilliland G, Kraft AS, Arnold CS. 1994. Interaction of the growth hormone receptor cytoplasmic domain with the JAK2 tyrosine kinase. Endocrinology 135:2228–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frank SJ, Yi W, Zhao Y, Goldsmith JF, Gilliland G, Jiang J, Sakai I, Kraft AS. 1995. Regions of the JAK2 tyrosine kinase required for coupling to the growth hormone receptor. J Biol Chem 270:14776–14785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sotiropoulos A, Perrot-Applanat M, Dinerstein H, Pallier A, Postel-Vinay MC, Finidori J, Kelly PA. 1994. Distinct cytoplasmic regions of the growth hormone receptor are required for activation of JAK2, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and transcription. Endocrinology 135:1292–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanderkuur JA, Wang X, Zhang L, Campbell GS, Allevato G, Billestrup N, Norstedt G, Carter-Su C. 1994. Domains of the growth hormone receptor required for association and activation of JAK2 tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 269:21709–21717 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Argetsinger LS, Campbell GS, Yang X, Witthuhn BA, Silvennoinen O, Ihle JN, Carter-Su C. 1993. Identification of JAK2 as a growth hormone receptor-associated tyrosine kinase. Cell 74:237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanner JW, Chen W, Young RL, Longmore GD, Shaw AS. 1995. The conserved box 1 motif of cytokine receptors is required for association with JAK kinases. J Biol Chem 270:6523–6530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu T, Goh EL, Lobie PE. 1998. Growth hormone stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation and association of p125 focal adhesion kinase (FAK) with JAK2. Fak is not required for stat-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem 273:10682–10689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown RJ, Adams JJ, Pelekanos RA, Wan Y, McKinstry WJ, Palethorpe K, Seeber RM, Monks TA, Eidne KA, Parker MW, Waters MJ. 2005. Model for growth hormone receptor activation based on subunit rotation within a receptor dimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12:814–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rowlinson SW, Yoshizato H, Barclay JL, Brooks AJ, Behncken SN, Kerr LM, Millard K, Palethorpe K, Nielsen K, Clyde-Smith J, Hancock JF, Waters MJ. 2008. An agonist-induced conformational change in the growth hormone receptor determines the choice of signalling pathway. Nat Cell Biol 10:740–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Udy GB, Towers RP, Snell RG, Wilkins RJ, Park SH, Ram PA, Waxman DJ, Davey HW. 1997. Requirement of STAT5b for sexual dimorphism of body growth rates and liver gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:7239–7244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Woelfle J, Chia DJ, Rotwein P. 2003. Mechanisms of growth hormone (GH) action. Identification of conserved Stat5 binding sites that mediate GH-induced insulin-like growth factor-I gene activation. J Biol Chem 278:51261–51266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Y, Jiang H. 2005. Identification of a distal STAT5-binding DNA region that may mediate growth hormone regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression. J Biol Chem 280:10955–10963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kofoed EM, Hwa V, Little B, Woods KA, Buckway CK, Tsubaki J, Pratt KL, Bezrodnik L, Jasper H, Tepper A, Heinrich JJ, Rosenfeld RG. 2003. Growth hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. N Engl J Med 349:1139–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwartzbauer G, Menon RK. 1998. Regulation of growth hormone receptor gene expression. Mol Genet Metab 63:243–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Edens A, Talamantes F. 1998. Alternative processing of growth hormone receptor transcripts. Endocr Rev 19:559–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He K, Wang X, Jiang J, Guan R, Bernstein KE, Sayeski PP, Frank SJ. 2003. Janus kinase 2 determinants for growth hormone receptor association, surface assembly, and signaling. Mol Endocrinol 17:2211–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He K, Loesch K, Cowan JW, Li X, Deng L, Wang X, Jiang J, Frank SJ. 2005. JAK2 enhances the stability of the mature GH receptor. Endocrinology 146:4755–4765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loesch K, Deng L, Wang X, He K, Jiang J, Frank SJ. 2007. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of growth hormone receptor in Janus kinase 2-deficient cells. Endocrinology 148:5955–5965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deng L, He K, Wang X, Yang N, Thangavel C, Jiang J, Fuchs SY, Frank SJ. 2007. Determinants of growth hormone receptor down-regulation. Mol Endocrinol 21:1537–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frank SJ, Fuchs SY. 2008. Modulation of growth hormone receptor abundance and function: roles for the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Biochim Biophys Acta 1782:785–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Y, Jiang J, Black RA, Baumann G, Frank SJ. 2000. TACE is a growth hormone binding protein sheddase: the metalloprotease TACE/ADAM-17 is critical for (PMA-induced) growth hormone receptor proteolysis and GHBP generation. Endocrinology 141:4342–4348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang X, He K, Gerhart M, Huang Y, Jiang J, Paxton RJ, Yang S, Lu C, Menon RK, Black RA, Baumann G, Frank SJ. 2002. Metalloprotease-mediated GH receptor proteolysis and GHBP shedding. Determination of extracellular domain stem region cleavage site. J Biol Chem 277:50510–50519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loesch K, Deng L, Cowan JW, Wang X, He K, Jiang J, Black RA, Frank SJ. 2006. JAK2 influences growth hormone receptor metalloproteolysis. Endocrinology 147:2839–2849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X, Jiang J, Warram J, Baumann G, Gan Y, Menon RK, Denson LA, Zinn KR, Frank SJ. 2008. Endotoxin-induced proteolytic reduction in hepatic growth hormone (GH) receptor: a novel mechanism for GH insensitivity. Mol Endocrinol 22:1427–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alves dos Santos CM, ten Broeke T, Strous GJ. 2001. Growth hormone receptor ubiquitination, endocytosis, and degradation are independent of signal transduction via Janus kinase 2. J Biol Chem 276:32635–32641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Kerkhof P, Smeets M, Strous GJ. 2002. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway regulates the availability of the GH receptor. Endocrinology 143:1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Putters J, da Silva Almeida AC, van Kerkhof P, van Rossum AG, Gracanin A, Strous GJ. 2011. Jak2 is a negative regulator of ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of the growth hormone receptor. PloS one 6:e14676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moulin S, Bouzinba-Segard H, Kelly PA, Finidori J. 2003. Jak2 and proteasome activities control the availability of cell surface growth hormone receptors during ligand exposure. Cell Signal 15:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Guan R, Jiang J, Kopchick JJ, Black RA, Baumann G, Frank SJ. 2001. Growth hormone (GH)-induced dimerization inhibits phorbol ester-stimulated GH receptor proteolysis. J Biol Chem 276:24565–24573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jiang J, Liang L, Kim SO, Zhang Y, Mandler R, Frank SJ. 1998. Growth hormone-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of a GH receptor-associated high molecular weight protein immunologically related to JAK2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 253:774–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang J, Wang X, He K, Li X, Chen C, Sayeski PP, Waters MJ, Frank SJ. 2004. A conformationally-sensitive GHR (growth hormone (GH) receptor) antibody: impact on GH signaling and GHR proteolysis. Mol Endocrinol 18:2981–2996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu J, Zhang Y, Berry PA, Jiang J, Lobie PE, Langenheim JF, Chen WY, Frank SJ. 2011. Growth hormone signaling in human T47D breast cancer cells: potential role for a growth hormone receptor-prolactin receptor complex. Mol Endocrinol 25:597–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang Y, Jiang J, Kopchick JJ, Frank SJ. 1999. Disulfide linkage of growth hormone (GH) receptors (GHR) reflects GH-induced GHR dimerization. Association of JAK2 with the GHR is enhanced by receptor dimerization. J Biol Chem 274:33072–33084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang N, Jiang J, Deng L, Waters MJ, Wang X, Frank SJ. 2010. Growth hormone receptor targeting to lipid rafts requires extracellular subdomain 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 391:414–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hammond DE, Carter S, McCullough J, Urbé S, Vande Woude G, Clague MJ. 2003. Endosomal dynamics of Met determine signaling output. Mol Biol Cell 14:1346–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Swaminathan G, Varghese B, Thangavel C, Carbone CJ, Plotnikov A, Kumar KG, Jablonski EM, Clevenger CV, Goffin V, Deng L, Frank SJ, Fuchs SY. 2008. Prolactin stimulates ubiquitination, initial internalization, and degradation of its receptor via catalytic activation of Janus kinase 2. J Endocrinol 196:R1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. VanderKuur JA, Wang X, Zhang L, Allevato G, Billestrup N, Carter-Su C. 1995. Growth hormone-dependent phosphorylation of tyrosine 333 and/or 338 of the growth hormone receptor. J Biol Chem 270:21738–21744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lobie PE, Allevato G, Nielsen JH, Norstedt G, Billestrup N. 1995. Requirement of tyrosine residues 333 and 338 of the growth hormone (GH) receptor for selected GH-stimulated function. J Biol Chem 270:21745–21750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang X, Darus CJ, Xu BC, Kopchick JJ. 1996. Identification of growth hormone receptor (GHR) tyrosine residues required for GHR phosphorylation and JAK2 and STAT5 activation. Mol Endocrinol 10:1249–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hansen LH, Wang X, Kopchick JJ, Bouchelouche P, Nielsen JH, Galsgaard ED, Billestrup N. 1996. Identification of tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain of the growth hormone receptor required for transcriptional signaling and Stat5 activation. J Biol Chem 271:12669–12673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stofega MR, Herrington J, Billestrup N, Carter-Su C. 2000. Mutation of the SHP-2 binding site in growth hormone (GH) receptor prolongs GH-promoted tyrosyl phosphorylation of GH receptor, JAK2, and STAT5B. Mol Endocrinol 14:1338–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Derr MA, Fang P, Sinha SK, Ten S, Hwa V, Rosenfeld RG. 2011. A novel Y332C missense mutation in the intracellular domain of the human growth hormone receptor does not alter STAT5b signaling: redundancy of GHR intracellular tyrosines involved in STAT5b signaling. Horm Res Paediatr 75:187–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yi W, Kim SO, Jiang J, Park SH, Kraft AS, Waxman DJ, Frank SJ. 1996. Growth hormone receptor cytoplasmic domain differentially promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 5b and 3 by activated JAK2 kinase. Mol Endocrinol 10:1425–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hackett RH, Wang YD, Sweitzer S, Feldman G, Wood WI, Larner AC. 1997. Mapping of a cytoplasmic domain of the human growth hormone receptor that regulates rates of inactivation of Jak2 and Stat proteins. J Biol Chem 272:11128–11132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gebert CA, Park SH, Waxman DJ. 1999. Termination of growth hormone pulse-induced STAT5b signaling. Mol Endocrinol 13:38–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ji S, Frank SJ, Messina JL. 2002. Growth hormone-induced differential desensitization of STAT5, ERK, and Akt phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 277:28384–28393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. de Vos AM, Ultsch M, Kossiakoff AA. 1992. Human growth hormone and extracellular domain of its receptor: crystal structure of the complex. Science 255:306–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Leung DW, Spencer SA, Cachianes G, Hammonds RG, Collins C, Henzel WJ, Barnard R, Waters MJ, Wood WI. 1987. Growth hormone receptor and serum binding protein: purification, cloning and expression. Nature 330:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frank SJ, Gilliland G, Van Epps C. 1994. Treatment of IM-9 cells with human growth hormone (GH) promotes rapid disulfide linkage of the GH receptor. Endocrinology 135:148–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang X, Cowan JW, Gerhart M, Zelickson BR, Jiang J, He K, Wolfe MS, Black RA, Frank SJ. 2011. gamma-Secretase-mediated growth hormone receptor proteolysis: mapping of the intramembranous cleavage site. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 408:432–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Govers R, ten Broeke T, van Kerkhof P, Schwartz AL, Strous GJ. 1999. Identification of a novel ubiquitin conjugation motif, required for ligand-induced internalization of the growth hormone receptor. EMBO J 18:28–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Landsman T, Waxman DJ. 2005. Role of the cytokine-induced SH2 domain-containing protein CIS in growth hormone receptor internalization. J Biol Chem 280:37471–37480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim SO, Jiang J, Yi W, Feng GS, Frank SJ. 1998. Involvement of the Src homology 2-containing tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 in growth hormone signaling. J Biol Chem 273:2344–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]