Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the visual system of patients suffering from type I or VI mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) by recording the visual evoked cortical potential (VECP).

Methods

Two patients with MPS VI and 2 patients with MPS I were tested before and after enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). A control group of 20 subjects was tested for statistical comparison. VECP was elicited by monocular stimulation with 1-Hz phase-reversal checkerboard patterns at 0.5 and 2 cycles per degree and with 16° of visual field. In all patients, both eyes were tested. VECP amplitude and latency were measured and compared with tolerance limits obtained from controls.

Results

MPS I and VI patients have a severe visual impairment that can be quantified by measuring VECPs. Even after several weeks of ERT, the visual impairment remained unaltered, indicating that the treatment had no significant influence on the visual conditions of MPS patients. Visual responses to high spatial frequencies were more deeply impaired than responses to low spatial frequencies. This can be explained by the kind of damage in the visual system that preferentially targets the eye optics.

Conclusion

VECPs can be used to monitor the degree of visual impairment of MPS patients and to check ERT efficacy.

Key words: Mucopolysaccharidosis, Enzyme replacement therapy, Visual evoked cortical potential, Glycosaminoglycans

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) are a rare group of inherited metabolic diseases with an incidence of about 1:25,000 in newborns worldwide and are characterized by the accumulation of complex molecules called glycosaminoglycans (GAG) in many tissues and organs. This accumulation is due to low or none lysosomal enzyme activity, which is needed for GAG catabolism [1]. About 11 different types of this disease have been identified and classified according to the defective enzyme. MPS patients present chronic and progressive clinical features, but symptoms may vary depending on each disease type. Organomegaly, multiplex dysostosis, hepatosplenomegaly, joint contractures, and characteristic facial changes are common findings of GAG tissue accumulation. Hearing dysfunctions, cardiorespiratory complications, low motility, and loss of visual acuity may also occur [1].

MPS VI visual dysfunction includes closed-angle and open-angle glaucoma [2] as well as optic nerve swelling and atrophy [3]. However, MPS I and VI visual acuity losses are generally associated with dermatan sulphate deposits in the cornea leading to an increase in the corneal thickness and corneal opacification [4, 5].

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) is an efficient MPS treatment based on the periodic replacement of the defective enzyme. ERT increases GAG degradation in tissues and significantly improves patients’ clinical condition; however, little is known about the ERT influence on patients’ vision [6, 7]. A recent study concluded that visual acuity and ocular findings had not deteriorated in 6 out of 7 MPS VI patients on ERT during a mean follow-up period of 3.5 years [8]. In the present study, we evaluated the visual system of children suffering from MPS I or VI by recording visual evoked cortical potentials (VECPs) [9].

Methods

Subjects

Four children were studied of whom 2 suffered from MPS VI (patients 1 and 2) and 2 from MPS I (patients 3 and 4). All patients had clinical manifestations of the disease and abnormally low lysosomal enzyme activity (table 1). VECP recordings were performed before ERT in all patients and after ERT in 3 of them (patients 1, 2, and 3). VECP recordings were also performed in healthy children (6 boys and 14 girls, 9.4 ± 2.2 years old) for statistical comparison. The eye refractive state was measured with an Automatic Refractor/Keratometer 599 (Zeiss Humphrey System, Dublin, Calif., USA) and then corrected to provide 20/20 visual acuity if necessary. Exclusion criteria comprised previous ocular, neural, or systemic diseases that could affect the visual system.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical and biochemical features of the MPS patients and ERT dosage a Clinical features of MPS patients b Biochemical analysis of MPS patients before ERT

| Patient No. (MPS type) | Age years | Sex | PC | ASO months | Blindness | Corneal opacification | Heart disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (VI) | 11 | Female | No | 14 | No | +++ | Mitral/aortic insufficiency |

| 2 (VI) | 9 | Female | No | 24 | No | ++ | Mitral/aortic insufficiency |

| 3 (I) | 18 | Male | Yes | <6 | No | ++++ | Mitral/aortic insufficiency |

| 4 (I) | 12 | Male | No | 60 | No | ++ | Mitral insufficiency |

| Patient No. (MPS type) | Urinary GAG μg/mg creatinine | Reference values μg/mg creatinine | Leukocyte enzyme activity nM/h/mg protein | Reference values nM/h/mg protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (VI) | 282.0 | 3.4–11 | 8.0 | 30–97 (ARSB) |

| 2 (VI) | 238.0 | 3.4–11 | 10.0 | 30–97 (ARSB) |

| 3 (I) | 313.8 | 1.5–7 | 0.03 | 13–62 (IDUA) |

| 4 (I) | 298.9 | 3.4–11 | 0.25 | 30–97 (IDUA) |

PC = Parents’ consanguinity; ASO = age of symptom onset; ARSB = arylsulphatase b; IDUA = α-L-iduronidase. Corneal opacification: + = attenuated; ++ = mild; +++ = moderate; ++++ = severe.

Ethics

This research was performed following the Brazilian and international regulations for ethics in research with human subjects (Ministério da Saúde, Brazil, 2000). It was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Tropical Medicine Nucleus, Federal University of Pará, Belém, Brazil (Report No. 045/2004 from June 30, 2004, and Report No. 103/2004 from November 4, 2004).

ERT

The recombinant enzymes laronidase (Aldurazyme®, recombinant human a-L-iduronidase; BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Novato, Calif., USA; Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, Mass., USA) and arylsulphatase b (Naglazyme®; BioMarin Pharmaceutical) were intravenously administered once each week for 4 weeks (1 mg/kg for MPS I and 0.58 mg/kg for MPS VI, respectively). For patients 1 and 2, enzyme reposition started 2 years before VECP evaluation. For patients 3 and 4, enzyme reposition started 6 months before VECP evaluation.

Visual Stimulation and VECP Recording and Analysis

All tests were performed monocularly. Visual stimulation, cortical recording, and signal analysis were previously described in details [10]. The methodology followed the ISCEV recommendations [9]. The stimulus consisted of 16 × 16° black and white checkerboards, 0.5 and 2 cycles per degree (cpd), 100% Michelson contrast, and 50 cd/m2 mean luminance, presented at 1-Hz square-wave pattern-reversal modulation.

Gold-cup surface electrodes were used to obtain one-channel recordings from Oz (active electrode), Fp (reference electrode), and Fpz (ground) [9]. The signal was recorded and processed using a Cambridge Research System (CRS, Rochester, UK) setup comprising a MAS800 differential amplifier, an AS-1 data acquisition card, an IBM Pentium PC, and the Optima for Windows software. Low temporal frequency presentation mode evokes transient responses with 3 main components: N75, P100, and N135 [9]. We measured the latency for the N75 and P100 components, as well as the peak-to-peak amplitude of the P100-N75 and P100-N135 components. In some cases where the N75 components were difficult to detect, the baseline-to-peak amplitude was measured.

Statistical Analysis

To characterize our control group, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and the interquartile range for the latency and amplitude at both spatial frequencies. MPS subject responses were measured and compared to the statistical tolerance intervals for 95% confidence and 90% population coverage [11].

Results

Normative Data

VECP was recorded from 20 normal subjects. The N75 VECP component was measurable in 17 (85%) and 20 (100%) subjects at 0.5 and 2 cpd, respectively. The P100 VECP component was measurable at 0.5 and 2 cpd in all subjects. The N135 VECP component was measurable in 12 (60%) and 18 (90%) subjects at 0.5 and 2 cpd, respectively, and had a broad range of latency values, varying from 132.8 to 244.1 ms at 0.5 cpd and from 142.6 to 219.7 ms at 2 cpd. Because of this variation, N135 measurements were not used in the present study to evaluate the patient's visual condition.

Statistics

Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and interquartile range for N75 and P100 latencies, as well as the N75-P100 peak-to-peak amplitude for both spatial frequencies that were studied, 0.5 and 2 cpd. The latency varied less than the amplitude and was more useful for patient visual assessment. A statistically significant difference was observed for N75 and P100 latencies at both 0.5 and 2 cpd (N75: F(4.12) = 26.44, P(0.05) = 1.05 × 10-5; P100: F(4.1) = 24.77, P(0.05) = 1.43 × 10-5), and both components had longer latencies at 2 cpd. The N75-P100 amplitude was not significantly different between the two spatial frequencies (N75-P100: F(4.1) = 2.5, P(0.05) = 0.1). The large variation in the P100-N75 amplitude makes it less reliable for statistical comparison between patients and normal subjects [12].

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and normative data of VECP components at 0.5 and 2 cpd for the control group and MPS patients a Descriptive statistics bNormative data of VECP parameters and values of MPS patients

| SF | n | Mean | SD | CV, % | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 cpd | Latency, ms | |||||

| N75 | 17 | 76.8 | 3 | 3.9 | 74.2–77.2 | |

| P100 | 20 | 106.1 | 3.2 | 3 | 104–108.4 | |

| Amplitude, mv | ||||||

| N75-P100 | 20 | 27.1 | 11.4 | 42 | 18.1–34.9 | |

| 2 cpd | Latency, ms | |||||

| N75 | 20 | 83.9 | 5 | 5.9 | 80.8–85.9 | |

| P100 | 20 | 114.2 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 109.4–116.2 | |

| Amplitude, mv | ||||||

| N75-P100 | 20 | 21.4 | 11.4 | 53.2 | 10.7–28.2 | |

| Latency, ms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N75 | P100 | ||

| Tolerance interval | 0.5 cpd | 69.7–83.9 | 98.7–113.4 |

| 2 cpd | 72.4–95.3 | 99.2–129.2 | |

| Patient 1 (MPS VI) | 0.5 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | 115.2* (RE), 114.3* (LE) |

| 2 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | 129.9* (RE), 142.6* (LE) | |

| Patient 2 (MPS VI) | 0.5 cpd | 89.8* (RE), 89.8* (LE) | 110.4 (RE), 114.3* (LE) |

| 2 cpd | 100.6* (RE), 99.6* (LE) | 130.9* (RE), 127 (LE) | |

| Patient 3 (MPS I) | 0.5 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR(LE) |

| 2 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR (LE) | |

| Patient 3 − 2R (MPS I) | 0.5 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR (LE) |

| 2 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR (LE) | |

| Patient 3 − 4R (MPS I) | 0.5 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR (LE) |

| 2 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR (LE) | |

| Patient 4 (MPS I) | 0.5 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | 110.4 (RE), 111.3 (LE) |

| 2 cpd | NR (RE), NR (LE) | NR (RE), NR (LE) | |

SF = Spatial frequency; SD = standard deviation; CV = coefficient of variation; IQR = interquartile range; 2R = second ERT; 4R = fourth ERT; RE = right eye; LE = left eye; NR = no response.

Value outside the tolerance interval.

Application of the Normative Data

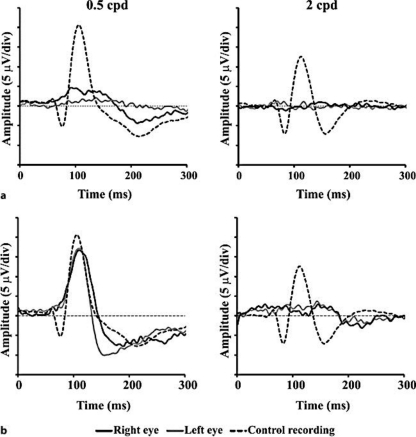

Fig. 1 and fig. 2 compare recordings obtained from MPS subjects (black and gray lines) with the grand mean recording from the control group (dotted lines) at 0.5 and 2 cpd (see also table 2 for numerical data). Fig. 1a and b shows VECPs obtained from MPS I patients 3 and 4, respectively, who had not received any ERT when the recordings were made. N75 was impaired in both patients at both spatial frequencies. P100 was impaired in patient 3 at both spatial frequencies and in patient 4 at 2 cpd. P100 had a normal amplitude and latency in patient 4 at 0.5 cpd.

Fig. 1.

VECPs from MPS patients at 0.5 and 2 cpd. a MPS I patient 3. b MPS I patient 4. None of the subjects were on ERT at the moment of recordings. Dotted lines represent the grand mean recordings from the control group. Bold and gray lines represent recordings obtained by stimulating the patients’ right or left eye, respectively.

Fig. 2.

VECPs from MPS patients. a, b MPS VI patients 1 and 2, respectively, 30 days after the unique enzyme reposition given to these subjects. c, d MPS I patient 3 1 day after the second enzyme reposition (a) and 68 days after the fourth reposition (b) at the two spatial frequencies studied, 0.5 and 2 cpd. Dotted lines represent the grand mean recordings from the control group. Bold and gray lines represent recordings obtained by stimulating the patients’ right and left eye, respectively.

Fig. 2 shows recordings obtained from subjects submitted to ERT. Fig. 2a and b shows the data from MPS VI patients 1 and 2, respectively, 30 days after the single enzyme reposition given to these subjects. N75 was impaired in patient 1 at both spatial frequencies and was present with a low amplitude and longer latency than controls in patient 2. P100 was present in both patients with normal (0.5 cpd) or reduced (2 cpd) amplitude and delayed latency at most conditions. Fig. 2c and d shows the data from MPS I patient 3, 1 day after the second ERT and 68 days after the fourth ERT, respectively. All VECP components were impaired in this patient in the whole series of recordings made. No changes were found before or after ERT for this and all other patients (see also table 2).

Discussion

This study suggests that patients suffering from both MPS I and VI have a severe visual impairment that can be quantified by measuring cortical evoked responses elicited by different spatial frequencies. In addition, even after several weeks of ERT, the visual impairment remained unaltered, indicating that ERT had no significant influence on the visual condition of MPS patients. Although this was the case for this group of patients, it would be desirable in future studies to increase the number of patients to monitor possible improvement of visual functions using VECPs.

In our patients, visual responses to a high spatial frequency (2 cpd) were more deeply impaired than responses to a low spatial frequency (0.5 cpd). This can be explained by the kind of damage in the visual system that preferentially targets the eye optics. The major systemic implications found in MPS patients are due to the deposition of GAG in many tissues and, consequently, the loss of function of many important organs [1, 13]. Dermatan sulphate is one of the most accumulated non-degraded GAG in corneal stroma and stromal keratocyte lysosomes of MPS I and VI patients [5]. The deposition of this compound in certain areas of the eye can promote a disruption of collagen fibrils responsible for the correct arrangement of visual structures, leading to corneal opacification. In addition, it can also increase intraocular pressure due to the blockade of anterior chamber structures, leading to ocular hypertension and glaucoma [14]. All these factors may contribute to a decrease in patients’ contrast sensitivity and visual acuity, independently of the clinical variations observed in each subtype of the disease.

This study demonstrates that it is possible to investigate the visual functions of MPS patients through objective, accurate, low-cost, and noninvasive electrophysiology such as that provided by VECP recording. For instance, VECP recording is more comfortable for subjects such as MPS patients than ERG recording and other techniques that need to probe the eye. Previous studies indicated some electroretinographic alterations under dark adaptation condition [5] and loss of visual acuity due to corneal opacification [15]. Similarly to electroretinograms, standard VECPs elicited from the primary visual cortex provide a functional analysis of vision regardless of the etiology of the visual impairment. For a thorough clinical analysis, it is necessary to compare VECP results and clinical findings, such as corneal opacification, as well as biochemical data. In agreement with the VECP results, corneal opacification remained unaltered after ERT in 3 patients and was more intense in the remaining one.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants CNPq-PRONEX/FAPESPA #2268; CNPq-PRONEX/FAPESPA #316799/2009; CNPq #620037/2008-3, #573993/2008-4, and #476744/2009-1; and FINEP/UFPA/FADESP #1723 (IBN Net). G.M.V. received a CNPq fellowship for graduate students. I.V.D.S., M.d.S.F., R.G., and L.C.L.d.S. are CNPq research fellows.

References

- 1.Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr. 2004;144:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantor LB, Disseler JA, Wilson FM. Glaucoma in the Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108:426–430. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins ML, Traboulsi EI, Maumenee IH. Optic nerve head swelling and optic atrophy in the systemic mucopolysaccharidoses. Ophthalmol. 1990;97:1445–1449. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casanova FH, Adan CB, Consuelo BD, Allemann N, de Freitas D. Findings in the anterior segment on ultrasound biomicroscopy in Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome. Cornea. 2001;20:333–338. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200104000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashworth JL, Biswas S, Wraith E, Lloyd IC. Mucopolysaccharidoses and the eye. Sur Ophthalmol. 2006;51:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miebach E. Enzyme replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2005;94:58–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Dib RP, Pastores GM. Laronidase for treating mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Gen Mol Res. 2007;6:667–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitz S, Ogun O, Arash L, Miebach E, Beck M. Does enzyme replacement therapy influence the ocular changes in type VI mucopolysaccharidosis? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:975–980. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-1030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odom JV, Bach M, Brigell M, Holder GE, McCulloch DL, Tormene AP, Vaegan ISCEV standard for clinical visual evoked potentials (2009 update) Doc Ophthalmol. 2010;120:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s10633-009-9195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Costa GM, dos Anjos LM, Souza GS, Gomes BD, Saito CA, Pinheiro Mda C, Ventura DF, da Silva Filho M, Silveira LC. Mercury toxicity in Amazon gold miners: visual dysfunction assessed by retinal and cortical electrophysiology. Environ Res. 2008;107:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon WJ, Massey FJ. The mean: estimation and tests of hypotheses. In: Dixon WJ, Massey FJ, editors. Introduction to Statistical Analysis. New York, Toronto, London: McGraw-Hill; 1957. pp. 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke LA. The mucopolysaccharidosis: a success of molecular medicine. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e1. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connell P, McCreery K, Doyle A, Darcy F, O'Meara A, Brosnahan D. Central corneal thickness and its relationship to intraocular pressure in mucopolysaccararidoses-1 following bone marrow transplantation. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strab. 2008;12:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz MF, Werblin TP, Green WR. Occurrence of mucopolysaccharide in corneal grafts in the Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome. Cornea. 1985;4:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stürmer J. Type VI-A mucopolysaccharidosis (Maroteaux-Lamy disease). Clinico-pathologic case report (in German) Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1989;194:273–281. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1046370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]