Abstract

Choroidal melanoma is the most common primary intra-ocular malignant tumor and second most common site of ten malignant melanoma sites in the body. Current diagnosis of choroidal melanoma is based on both the clinical experience of the specialist and modern diagnostic techniques such as indirect ophthalmoscopy, A- and B-ultrasonography scans, fundus fluorescein angiography, and transillumination. Invasive studies such as fine needle aspiration cytology can have significant morbidity and should only be considered if therapeutic intervention is indicated and diagnosis cannot be established by any other means. Several modes of treatment are available for choroidal melanoma. Multiple factors are taken into account when deciding one approach over other approaches, such as visual acuity of the affected eye, visual acuity of the contralateral eye, tumor size, location, ocular structures involved and presence of metastases. A comprehensive review of literature available in books and indexed journals was done. This article discusses in detail epidemiology, diagnosis, current available treatment options, and prognosis and survival of choroidal melanoma.

Keywords: Choroidal, eye, melanoma, review

Introduction

The choroid is the layer of the eye ball between the retina and sclera and is considered part of the uveal tract which is composed of the iris and ciliary body anteriorly and choroid posteriorly. The choroid has highest blood flow in the body. Choroidal melanoma is the most common primary Intra-ocular malignant tumor and second most common site of ten malignant melanoma sites in the body.[1] Current diagnosis of choroidal melanoma is based on both the clinical experience of the specialist and modern diagnostic techniques such as indirect ophthalmoscopy (IO), A- and B-ultrasonography scans, fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), and transillumination. Invasive studies suchas fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) can have significant morbidity and should only be considered if therapeutic intervention is indicated and diagnosis cannot be established by any other means. The rate of misdiagnosis of eyes enucleated for choroidal melanoma was approximately 20% duringthe years up to 1970, but diagnosis of choroidal melanoma has improved dramatically in the past 3 decades, and incorrect diagnosis since that time hasprogressively decreased to approximately 10%.[2–7] As a potentially lethal ocular condition, melanoma is feared both by patients and clinicians. A comprehensive review of the literature available in books and indexed journals was done. This article will discuss epidemiology, diagnosis, current available treatment options and prognosis of choroidal melanoma.

Epidemiology

Uveal melanoma is an uncommon disease. The incidence of primary choroidal melanomais about 6 cases per 1 million population in USA and about 7.5 cases per million peryear in Denmark and other Scandinavian countries.[8] Choroidal melanoma and other uveal melanomas most often affect Caucasians of Northern European descent. Incidence of choroidal melanoma among blacks is extremely rare. Hispanics and Asians are thought to have a small but intermediate risk compared to whites and blacks.[8–10] Uveal melanoma is rarely diagnosed in children.[10–13] In most series, the median age at diagnosis is about 55 years.[11–14] Choroidal melanoma is found slightly more frequently in men for all age groups, except in the group from 20 to 39 years, where a small predilection exists for women.[11,15–17] Nevi on the skin have been shown in several studies to increase the risk of cutaneous melanoma.[18,19]

The available literature suggests that risk of choroidal and ciliary body melanomas associated with nevi of the uveal tract is low.[20] In an analysis of 2514 choroidal nevi, factors predictive of growth into melanoma included greater thickness, subretinal fluid, symptoms, orange pigment, margin near disc, and twonew features: Ultrasonographic hollowness and absence of halo.[21] Hormonal influences are suspected to be a factor in cutaneous melanoma based on reports of an increased risk for women in their child-bearing years.[22,23] Acute or intense exposure to ultraviolet light might increase the risk of uveal melanoma, butthe role of acute or chronic sunlight exposure remains inconclusive.[24,25] Host factors remain the strongest known risk factors for this disease, particularlyancestry. Degree of pigmentation and cutaneous mole also appear to be markers of risk. There are also rare reports of uveal melanoma occurring in blood relatives. Occupational and chemical exposures merit further research so that the risk of this potentially fatal tumor may one day be reduced.

Genetics

Uveal melanomas are genetically homogenous, with few tumor-specific cytogenetic aberrations. Some of these aberrations correlate with the metastatic potential of the tumor, resulting in metastatic disease followed by death. Recurrent aberrations in uveal melanomas concern loss of 1p, monosomy of chromosome 3, loss of 6q and 8p, and gain of 6p and 8q.

Loss of chromosome 1p was observed in metastases,[26] and concurrent loss of 1p and chromosome 3 is associated with decreased survival.[27,28] Furthermore, monosomy 3 is considered to be an early event in UM, and several studies have shown that it is a strong predictor of survival.[29–31] Loss of chromosome 3 is frequently associated with amplification of 8q, often seen as isochromosome 8, q-arm.[32,33]

Diagnosis

History is not useful in diagnosing a uveal melanoma but it can be important in identifying a simulating lesion.

History: In general, many melanoma patients have asymptomatic tumor discovered on routine ophthalmic examination. Other patients with melanoma will besymptomatic complaining of visual loss, photopsiaand visualfield defects. Decreased vision is usually due to tumor encroachment on the fovea, exudative retinal detachment that involves the macula, or tumor contact with the lens. Symptoms such as severe pain are unusual for melanoma, except in cases of inflammation, massive extraocular extension or neovascular glaucoma. The past medical history may reveal a non-ocular malignancy, which would be suggestive of a metastatic lesion although one needs to be careful with this information because 6% to 10% of uveal melanoma patients have another primary neoplasm.[34,35]

-

Clinical examination and IO: IO through a well-dilated pupil is the most important examination in the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma. It has been reported that IO correctly diagnoses melanoma in more than 95% of cases.[7] The classic appearance of choroidal melanoma on IO is a pigmented dome-shaped or collar button-shaped tumor with an associated exudative retinal detachment. Choroidal melanoma is usually pigmented, but they can be variably pigmented and even amelanotic (non-pigmented). Usual findings are characteristic orange pigment (lipofuscin) at the level of retinal pigment epithelium, exudative retinal detachment (usually with melanomas greater than 4 mm in thickness). Some of large melanomas, especially involving the ciliarybody, have prominent episcleralvessels. It is important to recognize findings that are not typical of choroidal melanoma and that if seen, one should consider an alternative diagnosis. The presence of significant hemorrhage associated with a mass is rare in melanoma. Multiple choroidal tumors are not consistent with melanoma and should make one suspect metastasis or a lymphoid lesion.

A distinct orange purple color of tumor is more typical of choroidal hemangioma or an early choroidalosteoma. Dark black pigmentation is more commonly seen with retinal pigment epithelium hypertrophy or hyperplasia. The complete absence of pigmentation is seen in minority of melanoma cases and when the lesion is amelanotic, one should always consider the possibility of choroidalhemangioma or metastasis. Significant intraocular inflammation is also uncommon in melanoma and is more consistent with inflammatory diseases.

Ultrasonography: Combined A-mode and B-mode ultrasonography is the most important ancillary test [Figures 1 and 2]. On A-scan ultrasonography, choroidal melanoma shows medium to low internal echoes with smooth attenuation. Vascular pulsationswithin the tumor can also be seen by this mode. By B-scan three classic features of choroidal melanoma are: An acoustically silent zone within the melanoma, choroidal excavation and shadowing in the orbit. For tumors greater than 3 mm in thickness, a combination of A- and B-scan ultrasonography can diagnose choroidal melanomas with greater than 95% accuracy.[7] Nevi present as echo-dense and areminimally vascular.

Fluorescein angiography: Accuracy of fluorescein angiography in diagnosing choroidal melanoma is limited.[7] Large tumorsshow some characteristic patterns, but they are by no means pathognomic. Largermelanomas often have an intrinsic tumor circulation (double circulation), extensive leakage with progressive fluorescence, late staining of the lesion and multiple pinpoint leaks(hot spots) at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium.[36,37]

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): Melanomas demonstrate serous retinal detachment, debris on back of retina, retina of normal thickness, and intact photoreceptors. Nevi demonstrate photoreceptor loss (50% of cases), absolute scotoma, retinal atrophy and thinning, and pigment epithelial detachment (15% of cases)

Autofluorescence: Melanomas demonstrate clumps of hyperautofluorescence that correlate with clinically evident orange pigment. Nevi demonstrate no autofluorescence.

Indocyanine green angiography: This is capable of imaging the micro-circulation of choroidal melanomas.

Other Ancillary tests and procedures: High resolution computed tomography (CT) is less accurate than ultrasonography and is more expensive.[38,39] The role of magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrography in the diagnosis of melanoma is still uncertain.[40,41] Invasive techniques include the radioactive phosphorus uptake test and fine needle biopsy of the lesion. The radioactive phosphorus uptake test is no longer used because the rates of false negatives and false positives are quite high.[42] The role of fine needle biopsy is also uncertain because we cannow diagnose choroidal melanomas quite accurately without the use of invasive techniques. Interpretation of the tumor aspirates is quite difficult and subsequent seeding of the needle track has also been reported.[43]

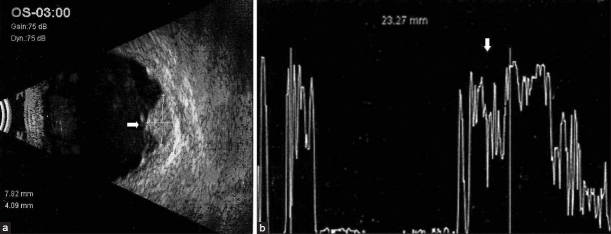

Figure 1.

(a) B-scan ultrasound showing a large mushroom-shaped mass lesion (arrow) noted nasally with sub-retinal fluid noted surrounding the mass lesion. (b) A-scan ultrasound of the same lesion showing internally medium reflectivity (arrow) in the lesion area

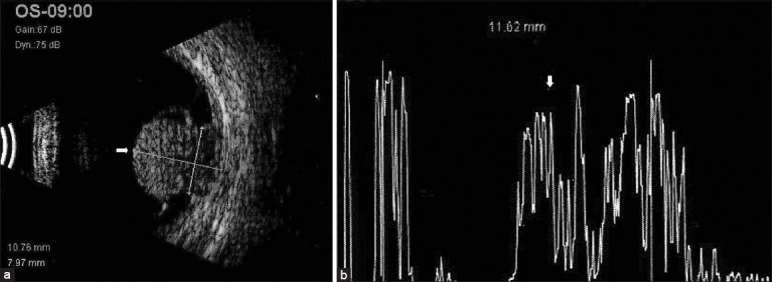

Figure 2.

(a) B-scan ultrasound showing a dome-shaped mass lesion temporal to disc at the macula area (arrow) with a shallow elevated high reflective membrane attached to the apex of the lesion. (b) A-scan ultrasound of the same lesion showing internally medium to high reflectivity (arrow) in the lesion area

Lesions that simulate choroidal melanoma

Few lesions masquerading as melanoma are choroidal nevus, choroidal metastasis, choroidal hemangioma, choroidal osteoma, melanocytoma, benign lymphoid tumor, choroidal hemangio-pericytoma, choroidal leiomyoma, extra-macular disciform lesion, ruptured arteriolar macroaneurysm, localized choroidal detachment, retinal pigment epithelial hypertrophy, posterior scleritis, haemorrhagic retinal detachment, massive retinal gliosis, retinalglioma.

Treatment

Several modes of treatment are available for choroidal melanoma. Multiple factors are taken into account when deciding one approach over other approaches, suchas visual acuity of the affected eye, visual acuity of the contralateral eye, tumorsize, location, ocular structures involved, and presence of metastases.

Treatment options for small choroidal melanoma

Thickness greater than 2 mm, fluid, symptoms, orange pigment, margin near disc, ultrasonographic hollowness, halo absence, and drusen absence are profoundly important risk factors for the detection of early choroidal melanoma. Patients with choroidal nevi showing no features of the disease should be initially monitored twice yearly and followed up annually thereafter if their condition is stable. Those with one or two features should be monitored every 4 to 6 months.[21] A small choroidal melanoma in the posterior fundus is amenable to several treatment options, including laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, plaque radiation therapy, external beam charged particle radiation therapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, location tumor resection, and enucleation.

Treatment options for medium and large choroidal melanomas

Enucleation has been the time honored method of management of the large ocular melanoma and melanomas that cause severeglaucoma or invade the optic nerve. One of the two clinical trials of the collaborative ocular melanoma study(COMS) compared preoperative external been radiation therapy plus enucleation to enucleation alone in patients with large choroidal tumors to address the concern that enucleation might precipitate tumor metastasis and shorten survival.[44] After 10 years of follow up, the cumulative all-cause mortality rate for each treatment arm was 61%. In addition, the 10 years rates of death withhistopathologically confirmed melanoma metastasis were not significantly different (45% in the preenucleation radiation and 40% in the enucleation alone). Thus, enucleation is considered primarily if there is a diffuse melanoma or if there is extraocular extension. Radiation complications or tumor recurrence may eventually make enucleation necessary.[45] Plaque brachytherapy is the most frequently used eye-sparing treatment for choroidal melanoma. Iodine-125, gold-198, palladium-103, and other ophthalmic plaques are used for partial to complete tumor regression.[46,47] Results have been generally encouraging but complications of radiotherapy include radiation retinopathy, cataract, vitreous hemorrhage, and neovascular glaucoma. Tumor recurrence contiguous to the treated area is about 12% of cases and rarely elsewhere in the eye has been noted. The most common material used in modern plaques is iodine-125 because of its lower energy emission (lack of alpha and beta rays), its good tissue penetration, and its commercial availability. In preparing an eye for brachytherapy, the most important tumor measurement is the largest basal diameter since a 2 mm margin of plaque around the base of the tumor is recommended to ensure adequate I-125 treatment to the entire tumor. Measurements are best made by ultrasonography, transillumination, or clinical comparison to the optic nerve. Radioactive plaques remain on the eye for 3-7 days depending upon the size of the tumor and rate of radiation delivery. The recommended radiation delivery for I-125 is 80-100 Gy to the tumor apex at a dose rate of 50-125 cGy/h. Confirmation of the location of the plaque can be done intra-operatively with ophthalmoscopy or ultrasound or with postoperative MRI.

Results from the second COMS clinical trial, which compared 125-I plaque brachytherapy to enucleation in patients with medium-sized choroidal tumors, revealed no significant difference in cumulative all-cause mortality between the two study arms at 12 years of follow-up (43% for 125-I plaque brachytherapy vs. 41% for enucleation; risk ratio=1.04; 95% CI, 0.86–1.24).[48] In addition, the 12-year rates of death with histopathologically confirmed melanoma metastasis did not differ significantly between the 2 study arm(21% in the 125-I brachytherapy arm and 17% in the enucleation arm, P=0.62). Among the patients treated with 125-I brachytherapy, 85% retained their eye for 5 years or more, and 37% had visual acuity better than 20/200 in the irradiated eye 5 years after treatment.[49]

External beam (charged particle) either heliumions or protons, may have several theoretical advantages over plaque therapy including optimal irradiation delivery to the entire tumor, with a theoretical reduction of radiation damage to surrounding normal tissue. External beam irradiation of melanomas with charged particles, protons, or helium nuclei has been performed since 1975. Proponents praise the treatment's accuracy and ability to treat larger tumors, up to 30% of the ocular volume.[50] Patients treated with proton beam irradiation had a 64% incidence of maculopathy for tumors within four disc diameters of the macula. Radiation therapy is about twice as expensive as enucleation. There appear to be no significant quality of life differences between patients treated with radiation or enucleation. Another radiation therapy technique occasionally employed but not as extensively studied is Gamma knife surgery. Preliminary evidence suggests that Gamma knife surgery may be feasible treatment option for medium sized choroidal melanomas.[49]

Eyewall resection or sclerouvectomy is a method of surgically removing an entire tumor, along with adjacent sclera and retina and grafting banked sclera to close the defect.[51] More recently, lamellar sclerouvectomy has been performed in order to avoid vitreoretinal complications of the full thickness procedure. Orbital exenteration is a radical treatment reserved for cases with widespread orbital extension. Orbital exenteration is a radical treatment reserved for cases with widespread orbital extension. Patients with such advanced melanomas are likely to have extensive distant metastases and poor prognosis for survival, with or without orbital exenteration surgery. The usefulness of such disfiguring surgery is not established and should only be considered in rare cases where marked discomfort is associated with massive orbital spread of the melanoma. Choice of treatment of choroidal melanoma remains controversial in many respects. Although enucleation has been the treatment of choice in the past, it appears that vision-sparing approaches might offer similar degrees of ocular and metastatic tumor control. Particularly, because it is clear that in many patients, at the time of diagnosis, posterior uveal melanomas already have spread through micrometastasis. In cases where distant metastases are found during the initial systemic workup, treatment of the intraocular melanomas becomes palliative. Systemic chemotherapy is the primary treatment in such cases.

Relative quality of life and emotional outcome, including physical function, psychological function, social and emotional function, and level of health problems must be considered in the treatment decision.[52] When patients make a treatment decision regarding choroidal melanoma, major factors are fear of death due to cancer and concerns regarding prognosis for vision in the affected eye. Patients often fear that enucleation will be disfiguring and also have fears of eventual poor vision or blindness in the fellow eye, even when this eye is healthy. Radiation therapy, on the other hand, causes concerns about residual viable tumor, compromised vision, ocular discomfort, and chronic ocular irritation. The cost difference between the two methods of treatment is considerable. Economic factors may become a consideration as well. The three most important determinants of the “success” of treatment for choroidal melanoma are survival, vision, and quality of life.[53] Patients treated with brachytherapy reported significantly better visual function than patients treated with enucleation with respect to driving and peripheral vision for up to 2 years following treatment. Differences between treatments in visual function diminish by 3 to 5 years after treatment, paralleling decline in visual acuity in brachytherapy-treated eyes. Patients treated with brachytherapy were more likely to have symptoms of anxiety during follow-up than patients treated with enucleation.[54]

Prognosis and survival

Uveal melanoma size is the most important clinical factor related to prognosis. Coupland et al.,[55] evaluated 847 patients with uveal melanoma for metastatic death and found clinical and histopathologic predictive factors of largest basal tumor diameter, closed loops, epithelioid cells, mitotic rate, and extraocular spread. Damato et al.[56] included genetic testing in their analysis for factors predictive of metastatic death and found the most important independent predictors to be basal tumor diameter, chromosome 3 loss, and epithelioid cell histopathology. Eskelin™.[57] explored tumor doubling times and speculated that most metastases initiate 5 years before primary treatment.

Despite the availability of alternative treatment modalities, the survival rates of patients with uveal tract melanoma have not changed in 30 years. Cumulative rates of metastases in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study at 5 and 10 years after treatment were 25% and 34%, respectively. Common sites of metastases include liver (90%), lung (24%), and bone (16%).[58,59] Patients with metastases confined to extrahepatic locations have longer survival (19–28 months).[57] The median survival for a hepatic metastasis is 6 months with an estimated survival of 15–20% at 1 year and 10% at 2 years, irrespective of treatment.[60,61] Asymptomatic patients at the time of diagnosis of metastases have a slightly longer survival in relation to symptomatic patients.[62]

Conclusion

In conclusion, choroidal melanoma can be diagnosed quite accurately with non-invasive techniques like IO, A- and B-ultrasonography scans, FFA, and transillumination, preventing complications of FNAC like seeding of tumor cells in the needle track. The role of CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectrography in the diagnosis of melanoma is still uncertain. Radioactive phosphorus uptake is no longer used because the rates of false negatives and false positives are quite high. Treatment for a small choroidal melanoma in the posterior fundus ranges from observation to several treatment options, including laser photocoagulation, plaque radiation therapy, external beam charged particle radiation therapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, location tumor resection, and enucleation. For medium and large lesions, enucleation is considered primarily if there is a diffuse melanoma or if there is extraocular extension. Plaque brachytherapy is the most frequently used eye-sparing treatment for these lesions. External beam (charged particle) either helium ions or protons may have several theoretical advantages over plaque therapy. Patients treated with proton beam irradiation had a 64% incidence of maculopathy for tumors within four disc diameters of the macula. But, radiation therapy is about twice as expensive as enucleation and there appear to be no significant quality of life differences between patients treated with radiation or enucleation. Other radiation therapy technique that has shown potential in preliminary studies is Gamma knife surgery. Considering the gamut of treatment options available, the treatment of choroidal melanoma needs to be individualized, keeping inmind various tumor characteristics and patient factors.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Albert DM. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. In: Albert, Jakobiec, editors. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co; 1994. pp. 3197–8. Ch. 258. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferry AP. Lesions mistaken for malignant melanoma of the posterior uvea: A clinicopathological analysis of 100 cases with ophthalmoscopically visible lesions. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;72:463–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1964.00970020463004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shields JA. Lesions simulating malignant melanoma of the posterior uvea. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:466–71. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1973.01000040468004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman LE. Bedell Lecture: Problems in the diagnosis of malignant melanoma of the choroid and ciliary body. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:917–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)91079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang M, Zimmerman LE, McLean IW. The persisting pseudomelanoma problem. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:726–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030582024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields JA, Augsburger JJ, Brown GC, Stephens RF. The differential diagnosis of posterior uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:518–22. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Char DH, Stone RD, Irvine AR, Crawford JB, Hilton GF, Lonn LI, et al. Diagnosticmodalities in choroidal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;89:223–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(80)90115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sotto J, Fraument JF, Jr, Lee JA. Melanomas of the eye and other noncutaneous sites: Epidemiologic aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;56:489–91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/56.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller B, Abrahams C, Code GC, Proctor NS. Ocular malignant melanoma in South African Blacks. Br J Ophthamol. 1981;65:720–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.10.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fledelius H, Land AM. Malignant melanoma of the choroids in an 11- month- old infant. Acta Ophthamol. 1975;53:160–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1975.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen OA. Malignant melanoma of the uvea in Denmark 1943-1952, aclinical histopathological, and prognostic study. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl (Copenh) 1963;43(Suppl 75):1–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul EV, Parneli BL, Fraker M. Prognosis of malignant melanomas of the choroid and ciliary body. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1962;2:387–402. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shields CL, Shields JA, Milte J, De Potter P, Sabbagh R, Menduke H. Uveal Melanoma in teenagers and children: A report of 40 cases. Ophthamology. 1991;98:1662–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raivio I. Uveal melanoma in Finland: An epidemiological, clinical, histological and prognosis study. Acta Opthalmol Suppl (Copenh) 1977;133:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gragoudas ES. First 1000 patients with uveal melanoma treated by proton beam irradiation. Second International Meeting on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Intraocular Tumors, in Nyon, Switzerland. 1987 Nov [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahoney MC, Burnett WS, Majerovics A, Tanenbaum H. The epidemiology of ophthalmic malignancies in New York State. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1143–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32445-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shammas HF, Blodi FC. Prognosis factors in choriodal and ciliary body melanomas. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:63–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450010065005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elwood JM, Willamson C, Stapleton PJ. Malignant melanoma in relation to moles, pigmentation, and exposure to fluorescent and other lighting sources. Br J Cancer. 1986;53:65–74. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1986.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holman CD, Armstrong BK. Pigmentary traits, ethnic origin, benign nevi, and family history as risk factors for cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Natl Cancer Ins. 1984;72:257–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganley JP, Comstock GW. Benign nevi and malignant melanomas of the choroid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;76:19–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields CL, Furuta M, Berman EL, Zahler JD, Hoberman DM, Dinh DH, et al. Choroidal nevus transformation into melanoma: Analysis of 2514 consecutive cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:981–7. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JA, Storer BE. Excess of malignant melanomas in woman in the British Isles. Lancet. 1980;2:1337–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JA, Storer BE. Malignant melanoma female/male death ratios. Lancet. 1981;1:1419. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher RP, Elwood JM, Rootman J, Spinelli JJ, Hill GB, Threlfall WJ, et al. Risk factors for ocularmelanoma: Western Canada Melanoma Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;74:775–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holly EA, Aston DA, Char DH, Kristiansen JJ, Ahn DK. Uveal melanoma in relation to ultraviolet light exposure and host factors. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5773–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aalto Y, Eriksson L, Seregard S, Larsson O, Knuutila S. Concomitant loss of chromosome 3 and whole arm losses and gains of chromosome 1, 6, or 8 in metastasizing primary uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:313–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilic E, Naus NC, van Gils W, Klaver CC, van Til ME, Verbiest MM, et al. Concurrent loss of chromosome arm 1p and chromosome 3 predicts a decreased disease-free survival in uveal melanoma patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2253–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hausler T, Stang A, Anastassiou G, Jöckel KH, Mrzyk S, Horsthemke B, et al. Loss of heterozygosity of 1p in uveal melanomas with monosomy 3. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:909–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Hirche H, Horsthemke B, Jockel KH, Becher R. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet. 1996;347:1222–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sisley K, Rennie IG, Parsons MA, Jacques R, Hammond DW, Bell SM, et al. Abnormalities of chromosomes 3 and 8 in posterior uveal melanoma correlate with prognosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;19:22–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199705)19:1<22::aid-gcc4>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White VA, Chambers JD, Courtright PD, Chang WY, Horsman DE. Correlation of cytogenetic abnormalities with the outcome of patients with uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1998;83:354–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Becher R. Two subclones in a case of uveal melanoma: Relevance of monosomy 3 and multiplication of chromosome 8q. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1994;77:144–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Friedrichs W, Seeber S, Becher R. Cytogenetics of twelve cases of uveal melanoma and patterns of nonrandom anomalies and isochromosome formation. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;80:40–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(94)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen OA. Malignantmelanomas of the uvea in Denmark 1943-1952. A clinical, histopathological, and prognostic Study. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1963;75:1–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lishko AM, Seddon JM, Gragoudas ES, Egan KM, Glynn RJ. Evaluation of prior primary malignancy as a determinant of uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1716–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gass JD. Problems in the differential diagnosis of chorodal nevi and malignant melanomas.The XXXIII Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83:299–323. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gass JD. Observation of suspected choroidal and ciliary body Melanomas forevidence of growth prior to enucleation. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:523–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mafee MF, Peyman GA, McKusick MA. Malignant uvel melanoma and similar lesions studied by computed tomography. Radiology. 1985;156:403–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.2.4011902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peyster RG, Augsburger JJ, Shields JA, Satchell TV, Markoe AM, Clarke K, et al. Choroidal melanoma: Comparison of CT, fundoscopy and ultrasound. Radiology. 1985;156:675–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.3.3895292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mafee MF, Peyman GA, Grisdano JF, Fletcher ME, Spigos DG, Wehrli FW, et al. Malignant melanoma and simulating lesions: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 1986;160:773–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.3.3737917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolodny NH, Gragoudas ES, D’Amico DJ, Albert DM. Magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy of intraocular tumors. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989;33:502–14. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(89)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shields JA. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of choroidal melanomas. Surv Ophthamol. 1977;21:443–63. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(77)80001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Augsburger JJ, Shield JA, Folberg R, Lang W, O’Hara BJ, Claricci JD. Fine needle biopsy in the diagnosis of intraocular cancer: Cytologic-histologic correlations. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawkins BS Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma: IV. Ten-year mortality findings and prognostic factors. COMS report number 24. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:936–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seregard S, Landau I. Transpupillary thermotherapy as an adjunct to ruthenium plaque radiotherapy for choroidal melanoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79:19–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2001.079001019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Earle J, Kline RW, Robertson DM. Selection of iodine 125 for the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:763–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060060049030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finger PT, Berson A, Szechter A. Palladium-103 plaque radiotherapy for choroidal melanoma: Results of a 7-year study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:606–13. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: V. Twelve-year mortality rates and prognostic factors: COMS report No. 28. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1684–93. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diener-West M, Earle JD, Fine SL, Hawkins BS, Moy CS, Reynolds SM, et al. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma, III: Initial mortality findings. COMS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:969–82. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gragoudas ES, Seddon J, Goitein M, Verhey L, Munzenrider J, Urie M, et al. Current results of proton beam irradiation of uveal melanomas. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:284–91. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodburn R, Danis R, Timmerman R, Witt T, Ciulla T, Worth R, et al. Preliminary experience in the treatment of choroidal melanoma with gamma knife radiosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:177–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.supplement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drummond M, Stoddart G, Torrence G. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1994. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruickshanks KJ, Fryback DG, Nondahl DM, Robinson N, Keesey U, Dalton DS, et al. Treatment choice and quality of life in patients with choroidal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:461–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melia M, Moy CS, Reynolds SM, Hayman JA, Murray TG, Hovland KR, et al. Quality of life after iodine 125 brachytherapy vsenucleation for choroidal melanoma: 5.year results from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study: COMS QOLS Report No. 3. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:226–38. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coupland SE, Campbell I, Damato B. Routes of extraocular extension of uveal melanoma risk factors and influence on survival probability. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1778–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Damato B, Duke C, Coupland SE, Hiscott P, Smith PA, Campbell I, et al. Cytogenetics of uveal melanoma: A 7-year clinical experience. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1925–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eskelin S, Pyrhönen S, Summanen P, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Kivelä T. Tumor doubling times in metastatic malignant melanoma of the uvea: Tumor progression before and after treatment. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1443–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willson JK, Albert DM, Diener-West M. Assessment of metastatic disease status at death in 435 patients with large choroidal melanoma in the collaborative ocular melanoma study (coms) coms report no.15. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:670–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, et al. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma.The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report 23. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2438–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bedician AY. Metastatic uveal melanoma therapy: Current options. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006;46:151–66. doi: 10.1097/01.iio.0000195852.08453.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, et al. Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report No. 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1639–43. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim IK, Lane AM, Gragoudas ES. Survival in patients with presymptomatic diagnosis of metastatic uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:871–5. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]