Abstract

Based on the pilot study carried out by the Office of the Dean of the Medical University of Ulm on the family-friendliness of the organisation of medical education in Ulm, this paper describes concrete measures that were designed at the university or have been partly implemented already.

More flexibility and customization are essential characteristics and prerequisites of a family-friendly medical school as part of university education structures. Flexibility and customization can be achieved by designing lesson plans and study regulations so that both childcare is assured and that in emergencies, help can be quickly offered with a minimum of bureaucracy.

More flexibility includes, amongst other things, adequate means for the individual to compensate for missed compulsory attendances and examination dates. The necessary shift in thinking and the willingness to cooperate on behalf of the management and teaching staff can be supported through the audit for family-friendliness “berufundfamilie” (job and family) or “familiengerechte hochschule” (family-friendly university), as well as strategic management tools of family-friendly corporate policies.

Supporting mechanisms such as effectively networked advice services, course progression monitoring based on data, providing a parents’ passport with a cross-semester training contract, creating more interaction between student-parents or other students through a parent community or by study pairings and finally, reliable information on and compliance with the maternity leave rules for pregnant and breastfeeding medical students can help safeguard successful studying with children.

Keywords: Career planning, family research, career-family balance, medical education

Abstract

Auf der Grundlage der durch das Studiendekanat Medizin der Universität Ulm durchgeführten Pilotstudie zur familienfreundlichen Studienorganisation der medizinischen Ausbildung in Ulm werden in diesem Beitrag konkrete Maßnahmen, die an der Universität konzipiert bzw. zum Teil bereits umgesetzt wurden, beschrieben.

Flexibilisierung und Individualisierung sind dabei wesentliche Merkmale und Voraussetzungen eines familienfreundlichen Medizinstudiums im Rahmen universitärer Ausbildungsstrukturen. Flexibilität und Individualisierung können dadurch erreicht werden, dass Stundenpläne und Studienordnungen so gestaltet werden, dass sowohl Kinderbetreuung gesichert ist, als auch in Notfällen schnell und unbürokratisch Hilfe angeboten werden kann.

Zur Flexibilisierung gehören u.a. adäquate, individuelle Kompensationsmöglichkeiten von Anwesenheitspflicht und Prüfungsterminen. Dafür erforderliche Bewusstseinsveränderung und Kooperationsbereitschaften beim Führungs- und Lehrpersonal können durch das Audit zur Familienfreundlichkeit „berufundfamilie“ bzw. „familiengerechte hochschule“, sowie ein strategisches Managementinstrument einer familienbewussten Unternehmenspolitik, gefördert werden.

Unterstützende Instrumente, wie ein effektiv vernetztes Beratungswesen, ein datengestütztes Studienverlaufsmonitoring, die Ausgabe eines Elternpasses mit einem semesterübergreifenden Ausbildungsvertrag, die Schaffung von mehr Austausch zwischen studierenden Eltern bzw. anderen Studierenden durch eine Elterncommunity bzw. durch Lerntandems und schließlich die verlässliche Aufklärung und Einhaltung der Mutterschutzregelungen für schwangere und stillende Medizinstudentinnen flankieren ein gelingendes Studium mit Kind(ern).

Introduction

In this paper, concrete measures are described which were developed and partly implemented at the University of Ulm on the basis of the Ulm pilot study on Studying Medicine with a Child [1] and the Baden-Württemberg study on Family-friendly Medical Studies [2], [3], [4]. This was done in cooperation with the teaching competence network Baden-Württemberg (http://www.medizin-bw.de) [5] and on behalf of the Ministry for Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Württemberg.

Despite high curriculum and family responsibilities, attending medical school with children is quite feasible [6], [7]. However, it requires binding and verifiable solutions to improve the flexibility of the curriculum and for compensating for missed teaching and examinations. Concrete measures that require an urgent implementation are, amongst other things, making student parents aware of university advice services, individual and flexible planning of the semester in the form of individualised study and family services, individual course monitoring [8], [9], moving the compulsory attendance courses to core working hours and extending the opening hours of childcare facilities. In a word, studying must be designed to suit individuals and to be more flexible.

The scientific Advisory Council for Family Affairs at the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth has dedicated a chapter to university level medical studies in their second edition of the report “Training, Studying and Parenting” and points out the urgent need for more family-friendly policies in healthcare [10]. In healthcare, the issues of family-friendliness and compatibility must be tackled at the undergraduate level to support the urgently needed young scientists in medicine [11]. Politics, university management and medical schools in Germany are equally called upon to offer reliable, flexible and individual solutions by expanding services, especially in the last third of medical studies [12]. Germany’s neighbours are also discussing the difficulties of reconciling a career in medicine and family [13], [14], [15], [16].

Auditing Family-friendliness

Since 2008, the University and the University Hospital of Ulm have been certified, and re-certified in 2011, by the audit “familiengerechte hochschule” and “berufundfamilie” through the berufundfamilie gGmbH of the Hertie foundation (http://www.berufundfamilie.de). Initial experiences in Ulm show that continuous auditing has initiated continuous changes in thinking, even if not all the planned measures for improvements, such as the childcare infrastructure, have been implemented yet (http://www.uniklinik-ulm.de/struktur/karriere/stellenangebote/audit-beruf-und-familie.html). The auditing puts both the university structures and the affected parents, whether students or employees, into a more favourable starting position which allows new concepts to be implemented, supportive policies to be formulated and access to appropriate funding.

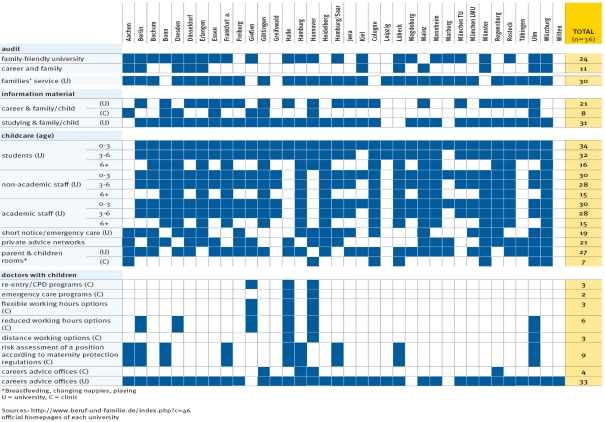

A web-search of leading medical universities in Germany shows that although 66.7% of universities are audited, only 30.6% of university clinics are. Career advice centres (91.7%) and family service offices (83.3%) are more frequently available at universities than university clinics (11.1%) (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1. Family friendly measures at universities offering medicine degrees.

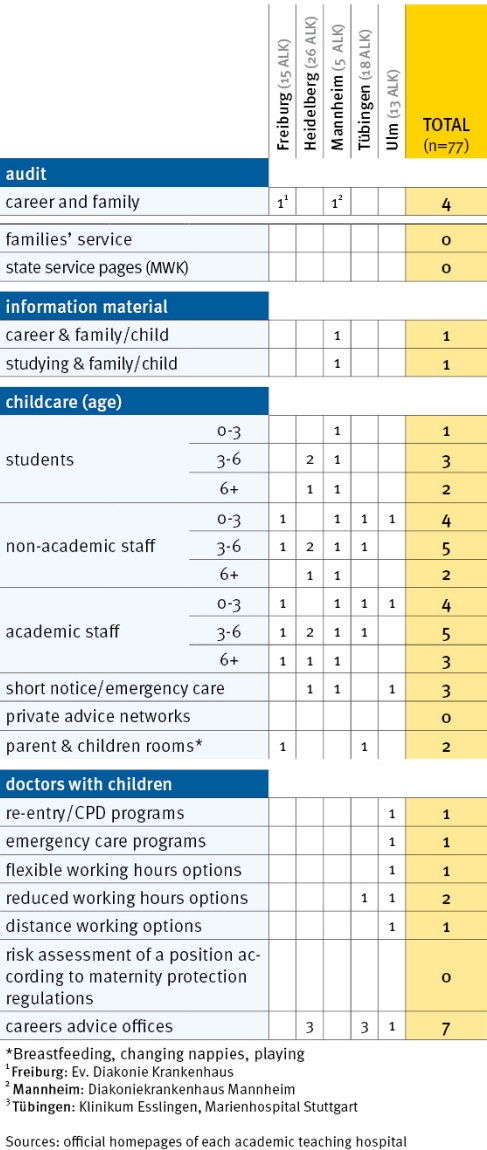

It is noticeable that while universities offer varied care services for children of all age groups, family-friendly measures such as re-entry programs, flexible working hours, reduced working hours, distance working options are rarely in place. Of the 77 academic teaching hospitals in Baden-Württemberg, only four received the certificate “berufundfamilie” (5.2%) and in-house childcare facilities are offered only infrequently (see Figure 2 (Fig. 2)).

Figure 2. Family-friendly measures at academic teaching hospitals in Baden-Württemberg.

Advice Network for Student Parents

University advice services for student parents are no longer restricted only to services offered by the university but increasingly moving towards needs-based approaches for individuals. It is noticeable that universities are characterised by a multitude of advice services and responsibilities that are often not transparent or self-explanatory for users. The advice needs of pregnant students or student parents for example include a variety of topics. Subjects touch upon questions about childcare, curricular matters, studying in chunks, study finance, legal matters, pregnancy and maternity as well as housing [1], [2], [17], [18], [19].

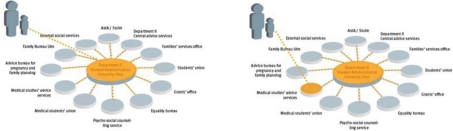

The responsibility for advice and support services and decisions about these lie centrally with the respective departments. The problem is that advice services are often linked with concrete support and service offers which are often located elsewhere (such as course selection support, certificates), which can result in long walking distances. A central clearing office, for example the administrative centre for tuition fees, could take on a role as central coordinator (see Figure 3 (Fig. 3)) which should enable networking the services more closely, defining professional responsibilities more clearly, synchronising office hours and merging offices at a given locality, for example of parent advice sessions. It should be ensured that the services are transparent to people outside the administration. A ground-breaking family service of this nature has now been established at the University of Ulm, which acts as an interface between the various university and external partners.

Figure 3. Network model of advice services.

In addition, advice should be evidence-based, which means that advice on the further progression of studies must be given on the basis of empirical findings [20]. The first attempts at implementation shown in the following have already proven themselves in medical studies as the demand for advice sessions has increased. An empirical foundation makes it possible to advise students with children or wishing to have children in selecting a course choice that will perhaps enable them to start a family while studying.

Medical studies with its low degree of course choices is very rigid and inflexible [1]. Students have little scope for setting individual priorities, both regarding the timing and content. The course design is complicated further by the fact that specific information for each semesters (such as rotation schedules or course lists) are provided on short notice. For the compatibility of family and studies, long-term planning however is required. At the Faculty of Medicine in Ulm students with children have routinely been offered advance course scheduling for the past 8 years.

Monitoring Study Progression

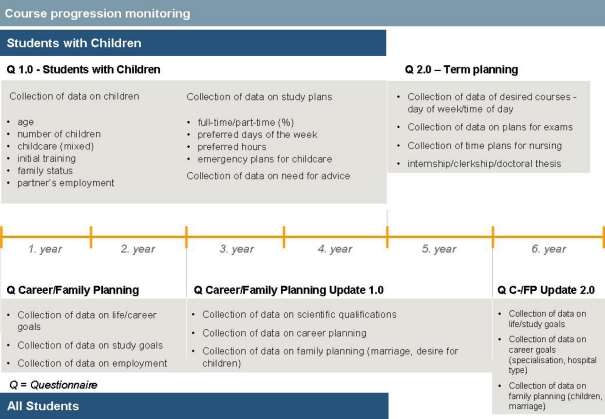

The concept of monitoring course progression [8] describes a tool which supports individual study paths, based on the real-life conditions of students [21] (see Figure 4 (Fig. 4)).

Figure 4. Monitoring Study Progression.

Based on Pixner [22], IT-based monitoring is used in Ulm (results management system, the online registration system Corona). Monitoring the courses progression through the academic advice services and assessing the study workload has become necessary due to the decreasing course flexibility in medical school, increases in the range of subjects and rapid changes in the curriculum. Systematic course progression monitoring may help to improve individual advice for students with children through degree course managers with regard to the complexity and interconnectedness of life and studies.

Advice should be given a lifelong perspective and the target or “risk groups” and their specific problems should be taken into greater account [23].

Evidence-based longitudinal advice to student parents offers continuous supervision across the entire course of studies through the academic advice services. Voluntary monitoring of course progression for student parents is based on a thorough analysis of the course progression data (data gathering on living conditions such as personal details, information about children, location, travel time, family and institutional childcare, course time preferences, feasible course volume, performance level, short-, medium- and long-term time budget planning, etc.) and includes a face to face meeting every semester. The course progression, including participation in the presence-required courses and exams, is demand-driven and individually adjusted so that the study load is compatible with family responsibilities.

Parent Pass

The parent pass is a chip-card which could be offered to all student parents (see Figure 5 (Fig. 5)).

Figure 5. Parent Pass of the University of Ulm.

A parent pass could ease access to infrastructure benefits and organizational assistance. University services for families (e.g. use of family car parks, shared hospital shuttle, electronic door key to family rooms, derogation of the examination regulations, early course registration, learning partner matching) could be preferentially accessed. A parent pass should contain a detailed explanation of the special services offered for student parents to inform teaching staff and other university employees about the specific situation of the student parent and to provide guidelines for solving issues. In case of conflicts, parent passes could help to clarify the rights of student parents within the teaching system. A university will only be family-friendly when families on campus have become a normality and students with children no longer have to take the role of petitioners. The concept of a parent pass is currently being evaluated and discussed in the appropriate offices at the University of Ulm.

Faculty Internal Training Contract

As a further means of support for the Dean(ery) of Students, a faculty-internal “training contract” between students and the dean can be set up, based upon data from the course progression monitoring. A training contract will be agreed for one academic year and, if necessary, over a longer period (study phase design). By having longer-term training contracts, students get planning security for the course progression, for example, clinical training, internships, thesis or family matters (such as childcare exchanges with a partner or grandparent, school entry phase). But special conditions for student parents are only justifiable if in accordance with the principles of equality as requirements for attendance or examinations must apply equally to all students. A first testing phase began in 2010.

Maternity Protection Guidelines and Awareness Training

Our studies [1], [2] have shown that universities and university clinics in Baden-Württemberg to date have no standardised mechanisms or advisory services to ensure they meet statutory maternity leave for student parents in medicine, even if the law expects clear guidelines for maternity provision at university (§ 3 Paragraph 1, § 6 Paragraph 1 of the Act for the Protect of Working Mothers (Maternity Protection Act - MuSchG) and § 15 Paragraph 1 to 3 of the Federal Parental Benefits and Parental Leave Act (BGBI)). In future, all female students should be informed about the dangers of pregnancy and breastfeeding in the medical field at the beginning of and during their studies [24], for example regarding hazardous materials in practical exercises. The University Hospital of Ulm has already developed such a scheme for pregnant students in their internship year (PJ) based on a similar scheme for pregnant doctors (see Figure 6 (Fig. 6)).

Figure 6. Registration procedures for pregnant PJ students.

The German Federation of Female Doctors take a critical view of the statutory maternity provisions because as they claim they constitute a general work prohibition, leaving no room for individual risk reduction [10], which is also true in some cases of medical internships. In the case of pregnancy, the university should provide pregnancy advice to prevent an exaggerated and too rigid interpretation of maternity protection, perhaps in cooperation with the pregnancy advice centre of the City of Ulm which also informs about the relevant risk assessments for each employment domain. This is a resource available to the university hospital. Systematic training through the course guidance office is provided each year through a centrally organised safety instruction and guidance event and through a guide on maternity provision. An information platform (Moodle) with information about the training limitations through health risks during pregnancy is available to students and teachers (https://www.lernplattform.medizin.uni-ulm.de/moodle).

Parent Community

Student parents often struggle with loss of contact with fellow students to an extent highly dependent on the individual and the particular circumstance of each student [1]. The reasons for this on the one hand lies in the restrictions on “typical student life” and the retreat to family responsibilities due to the founding of a family. On the other hand, student with children who are usually older than the average medical students [1], find it difficult to connect with the younger students following the standard timetables and are separated from their original student cohort through the family phase when they resume their studies at a later point. Family-oriented learning groups tend to develop more in a university-family environment, for example through meeting people outside the nursery when picking up or dropping off children [1].

Developing a parent community is conceivable, for example by forming a “UniUlm family network” which could serve as a meeting place for students but also employees with children. In addition, events for families could be offered at the university (“UniUlm Family Day”). A parent community could also help improve the social integration into university life and remove barriers for students with no children.

In addition to family-oriented events the creation of an internet meeting place is also desirable. A chat forum for medical students with children was set up on the learning platform Moodle, promoting exchanges between students with children or students wanting children.

Learning Partner Exchange: Learning Support during Transitional Phases

The transitions are critical phases facing student parents due to the family phase, either through possible interruptions of studies or following specialisation. Entry to academic studies with its university teaching and learning styles is especially difficult for students who have already completed some form of professional training previously [1], [2], especially if they already have children. Student parents should be offered learning support during such re-entry phases. Study pairings are conceivable between students with and without children. Self-organised student study groups are very time intensive and require matching time slots, something student parents within a larger study group cannot handle. The study pairing model would have the advantage that any appointments are between two people only and thus easier to arrange; the pairings could be coordinated flexibly and also offer opportunities for share study tasks beyond pure revision. Ideally, the result would be a win-win situation for both sides. The concept of learning pairings is not currently implemented.

Information Platform for Training Centres

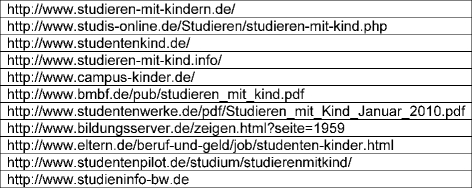

When entering the search terms “Studieren mit Kind” (Studying with a child) on http://www.google.de, approximately 187,000 results are returned, including a number of private initiatives in addition to information services offered by universities, student unions and ministries. The relevant websites are summarized in Figure 7 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Relevant websites for students with children [25.02.2011].

All websites listed inform the target group, students with children, about the compatibility of studies and family issues, with topics ranging from financing and government support and childcare to advice services and regulatory information (e.g. study leave, study extensions). Via Medici offers specialist information for the medical field (http://www.thieme.de/viamedici/medizinstudium/studium_kind/) and some medical faculties such as Berlin, Hannover, Frankfurt, Cologne and Ulm offer detailed information on studying medicine with children.

Multiple search results on Google [8.070 hits, 25.02.2011] based on a search for “Medizinstudium mit Kind” link to the initiative by the University of Ulm and its publications.

In cooperation with the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Württemberg, an internet platform for studying with children in the health and natural sciences is planned for July 2011, specifically designed for the target groups “training institutions and teachers” on the basis of the existing ministerial student information platform http://www.studieren-mit-kindern.de/. Content of the platform will include aspects specific to medicine and the sciences which must be followed (including maternity provisions, hazards during pregnancy, risk assessments of (clinical) placements, for example, working on a ward, surgery). In addition it aims to address questions about the curricular and legal forms of family-friendly teaching and research as flexible and individual solutions which can be described using examples on a platform are needed especially in medicine where time-consuming studies coincide with research activities as part of doctoral thesis.

Curricular and Legal Aspects

Curricular problems for students with children arise from the lack of course flexibility and the rigid weekly schedule. Lectures or exams at the ends of core hours (9am-4pm) complicate the organisation of childcare. Two thirds of student parents surveyed want morning teaching [1], [2]. Clinical block placements are usually organised as a full-time internships which cannot be taken part-time. Temporally isolated lectures with no links to attendance-compulsory events as well as hour-long free time windows during the day further complicate study. Mostly preclinical courses are held in rotation on weekdays through fixed lab set-ups, making childcare difficult to arrange. Course schedules and class lists are published just shortly before the semester begins. Making this information available by the end of previous semester would be preferable. One method particularly suitable for theoretical instruction is the use of web-based learning. At the University of Ulm, lecture recordings are now often made available on Moodle with controlled access.

The order of semesters and entry requirements for courses laid out in the study regulations may delay study if parents cannot attend all events in the required order and to the extent required. The prescribed minimum attendance regulations create problems for student parents, especially in emergencies, for example due to a sick child. A possible alternative solution would be to enable compensating for missed days or exams by attending catch-up opportunities. The regulations on absence during the internship year allow a maximum of 20 days off sick with no regard to sick children as prescribed in the SGB Book V § 45 employees with obligatory insurance (10 days; 20 days for single parents). And finally, the non-academic parts of training (nursing internship, clerkship) can only be absolved during the holidays and not part-time (ÄAppO § § 6.1 and 7.4).

Conclusions

The key characteristics of a family-friendly curriculum are flexibility and individualisation of study procedures. Various supporting measures facilitate the compatibility of family and medical studies without minimising the content requirements for student parents. Apart from improving the infrastructure of advice services with reliable instruments, such as the parent pass, monitoring course progression, training contracts etc. and the communication structure of student parents (including web-based parent communities, learning pairings), the weekly timetable should be modified and alternative groups should be offered during core hours as a matter of course, ideally in the mornings. Early announcement of rotation schemes allow reliable compatibility planning. A compensation scheme for missed events or examinations would increase flexibility and should be explicitly stated in the study regulations. Finally, the audit for family-friendliness should be highly recommended if educational medical institutions aim to achieve culture change which includes a shake-up of traditional role distributions.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Liebhardt H, Fegert JM. Medizinstudium mit Kind: Familienfreundliche Studienorganisation in der medizinischen Ausbildung. Lengerich: Pabst Sciences Publisher; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niehues J, Prospero K, Liebhardt H, Fegert JM. Familienfreundlichkeit im Medizinstudium in Baden-Württemberg. Ergebnisse einer Studie. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29(2):Doc33. doi: 10.3205/zma000803. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liebhardt H. Wie können Medizinstudium und Arztberuf familienfreundlicher werden? Hartmannbund BW aktuell. 2010;2(11):4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prospero K, Niehues J, Liebhardt H, Fegert JM. Studie: Zeit für Familiengründung während des Medizinstudiums? Ärztin. 2010;57(3):15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fegert JM, Obertacke U, Resch F, Hilzenbecher M. Medizinstudium: Die Qualität der Lehre nicht dem Zufall überlassen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2009;7:290–291. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liebhardt H, Stolz K, Mörtl K, Prospero K, Niehues J, Fegert JM. Familiengründung bei Medizinerinnen und Medizinern bereits im Studium? Ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie zur Familienfreundlichkeit im Medizinstudium an der Universität Ulm. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2011;28(1):Doc14. doi: 10.3205/zma000726.. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebhardt H, Fegert JM, Dittrich W, Nürnberger F. Medizin studieren mit Kind. Ein Trend der Zukunft? Dtsch Arztebl. 2010;107(34-35):1613–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liebhardt H, Stolz K, Mörtl K, Prospero K, Niehues J, Fegert JM. Evidenzbasierte Beratung und Studienverlaufsmonitoring für studierende Eltern in der Medizin. Z Berat Stud. 2010;2:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebhardt H, Stolz K, Mörtl K, Prospero K, Niehues J, Fegert JM. Evidenzbasierte Beratung und Studienverlaufsmonitoring für studierende Eltern in der Medizin. Hochschulwesen. 2011;59(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. Ausbildung, Studium und Elternschaft. Analysen und Empfehlungen zu einem Problemfeld in Schnittpunkt von Familien- und Bildungspolitik. Gutachten des wissenschaftlichen Beirats für Familienfragen beim Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. 2. Auflage. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Familie,Senioren,Frauen und Jugend; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bühren A, Schoeller E. Familienfreundlicher Arbeitsplatz für Ärztinnen und Ärzte. Lebensqualität in der Berufsausübung. Berlin: Bundesärztekammer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fegert JM, Niehues J, Liebhardt H. Familienfreundlichkeit in der Medizin. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29(2):Doc38. doi: 10.3205/zma000808. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carr P, Ash AS, Friedman RH, Scaramucci A, Barnett, RC, Szalacha L, Palepu A, Moskowitz MA. Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Ann Int Med. 1998;129(7):532–538. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cujec B, Oancia T, Bohm C, Johnson D. Career and parenting satisfaction among medical students, residents and physician teachers at a Canadian medical school. Can Med Ass J. 2000;126(5):637–640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox G, Schwartz A, Hart KM. Work-family balance and academic advancement in medical schools. Acad Psych. 2006;30(3):227–234. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.227. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed V, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Career obstacles for women in medicine: an overview. Med Educ. 2001;35(2):139–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittring B. Unterstützung und Beratung von Schwangeren und Studierenden mit Kind(ern) in München. In: Cornelißen W, Fox K, editors. Studieren mit Kind.Die Vereinbarkeit von Studium und Elternschaft: Lebenssituationen, Maßnahmen und Handlungsperspektiven. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Middendorff E. Studieren mit Kind. Ergebnisse der 18. Sozialerhebung des Deutschen Studentenwerks. Bonn/Berlin: Hochschul-Informations-System; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middendorff E, Weber S. Studentischer Bedarf an Service- und Beratungsangeboten - Ausgewählte empirische Befunde. Z Berat Studium. 2006;1:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winteler A, Forster P. Wer sagt, was gute Lehre ist? Evidenzbasiertes Lehren und Lernen. Hochschulwes. 2007;55:102–109. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurscheid C. Das Problem der Vereinbarkeit von Studium und Familie. Eine empirische Studie zur Lebenslage Kölner Studierender. Münster: LIT-Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pixner J. IT-gestütztes Monitoring von Studienverlaufsdaten Erfahrungen aus dem Pilotprojekt. In: Jäger M, Sanders S, editors. Modularisierung und Hochschulsteuerung - Ansätze modulbezogenen Monitorings. Hannover: Hochschul-Informations-System; 2009. pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sixt A, Weber PC. Beratung in lebensbegleitender Perspektive. Neue Herausforderungen für Hochschule und Beratung. Z Berat Stud. 2007;2:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier-Gräwe U. Modellprojekt "Studieren und Forschen mit Kind": Abschlussbericht. Gießen: Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen; 2008. [Google Scholar]