Abstract

DNA hydroxymethylation is a long known modification of DNA, but has recently become a focus in epigenetic research. Mammalian DNA is enzymatically modified at the 5th carbon position of cytosine (C) residues to 5-mC, predominately in the context of CpG dinucleotides. 5-mC is amenable to enzymatic oxidation to 5-hmC by the Tet family of enzymes, which are believed to be involved in development and disease. Currently, the biological role of 5-hmC is not fully understood, but is generating a lot of interest due to its potential as a biomarker. This is due to several groundbreaking studies identifying 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse embryonic stem (ES) and neuronal cells.

Research techniques, including bisulfite sequencing methods, are unable to easily distinguish between 5-mC and 5-hmC . A few protocols exist that can measure global amounts of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the genome, including liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry analysis or thin layer chromatography of single nucleosides digested from genomic DNA. Antibodies that target 5-hydroxymethylcytosine also exist, which can be used for dot blot analysis, immunofluorescence, or precipitation of hydroxymethylated DNA, but these antibodies do not have single base resolution.In addition, resolution depends on the size of the immunoprecipitated DNA and for microarray experiments, depends on probe design. Since it is unknown exactly where 5-hydroxymethylcytosine exists in the genome or its role in epigenetic regulation, new techniques are required that can identify locus specific hydroxymethylation. The EpiMark 5-hmC and 5-mC Analysis Kit provides a solution for distinguishing between these two modifications at specific loci.

The EpiMark 5-hmC and 5-mC Analysis Kit is a simple and robust method for the identification and quantitation of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine within a specific DNA locus. This enzymatic approach utilizes the differential methylation sensitivity of the isoschizomers MspI and HpaII in a simple 3-step protocol.

Genomic DNA of interest is treated with T4-BGT, adding a glucose moeity to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. This reaction is sequence-independent, therefore all 5-hmC will be glucosylated; unmodified or 5-mC containing DNA will not be affected.

This glucosylation is then followed by restriction endonuclease digestion. MspI and HpaII recognize the same sequence (CCGG) but are sensitive to different methylation states. HpaII cleaves only a completely unmodified site: any modification (5-mC, 5-hmC or 5-ghmC) at either cytosine blocks cleavage. MspI recognizes and cleaves 5-mC and 5-hmC, but not 5-ghmC.

The third part of the protocol is interrogation of the locus by PCR. As little as 20 ng of input DNA can be used. Amplification of the experimental (glucosylated and digested) and control (mock glucosylated and digested) target DNA with primers flanking a CCGG site of interest (100-200 bp) is performed. If the CpG site contains 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, a band is detected after glucosylation and digestion, but not in the non-glucosylated control reaction. Real time PCR will give an approximation of how much hydroxymethylcytosine is in this particular site.

In this experiment, we will analyze the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine amount in a mouse Babl/C brain sample by end point PCR.

Keywords: Neuroscience, Issue 48, EpiMark, Epigenetics, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-methylcytosine, methylation, hydroxymethylation

Protocol

1. DNA Glucosylation and Control Reactions

In a 1.5 milliliter reaction tube on ice, mix 5-10 micrograms of genomic DNA (for a final concentration of 30 micrograms /milliliter), 12.4 microliters of UDP-Glucose (for a final concentration of 80 micromolar), 31 microliters of NEBuffer 4 and up to 310 microliters nuclease-free water to bring the total volume to 310 microliters.

Split this reaction mixture into two tubes of 155 microliters each.

Then add 30 units, or 3 microliters, of T4-β-glucosyltransferase to one tube. Mix well by gently pipetting up and down. The second tube is the control reaction, so add 3 microliters of water, instead of T4-BGT.

Incubate both tubes at 37 degrees Celsius for 12 to 18 hours, during which time the T4-BGT will add glucose to the hydroxyl group of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine groups in the sample.

2. Restriction Enzyme Digestion

Label three 0.2 milliliter PCR-strip tubes numbers 1 through 3. Aliquot 50 ul of the reaction mixture into each.

Label three 0.2 milliliter PCR-strip tubes numbers 4 through 6. Aliquot 50 ul of the control mixture into each.

Add 100 units, or 1 microliter, of MspI into tubes 1 and 4. Mix well by gently pipetting up and down.

Add 50 units, or 1 microliter, of HpaII into tubes 2 and 5. Mix well by gently pipetting up and down.

Do not add anything to tubes 3 and 6, as they are controls.

Incubate all 6 tubes at 37 degrees Celsius for at least 4 hours.

Add 1 microliter of Proteinase K into each tube and incubate at 40 degrees Celsius for 30 minutes.

Inactivate the Proteinase K by incubating at 95 degrees Celsius for 10 minutes.

3. Analyze DNA by PCR/qPCR

This protocol uses NEB's LongAmp Taq for end-point PCR which has been shown to perform well. Other PCR protocols can be substituted.

Add the following components to a 0.2 milliliter PCR reaction tube on ice: 10 microliters of 5X LongAmp Taq Reaction Buffer, 1.5 microliters of 10 millimolar dNTPs, 1 microliter of 10 micromolar Forward Primer, 1 microliter of 10 micromolar Reverse Primer, 3 microliters of template DNA from the previous steps, 1 microliter of LongAmp Taq DNA Polymerase, and nuclease-free water up to 50 microliters. These volumes may change according to the PCR protocol used.

Gently mix the reaction. If necessary, collect all liquid to the bottom of the tube by a quick spin.

Overlay the sample with mineral oil if using a thermocycler without a heated lid.

Transfer the PCR tubes from ice to a thermocycler with the block preheated to 94 degrees Celsius and start the cycling program. For a routine 3-step PCR, there should be one initial denaturation step at 94 degrees Celsius for 30 seconds followed by 30 cycles of 94 degree Celsius denaturation for 15 seconds, 55 to 65 degree Celsius annealing for 30 seconds, and 65 degree Celsius extension for 20 seconds, or 50 seconds per kb. This should be followed by one final extension at 65 degrees Celsius for 5 minutes. Real-time PCR can also be performed to quantitate amounts of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Please refer to the product manual, found on neb.com for specific information.

4. Representative Results:

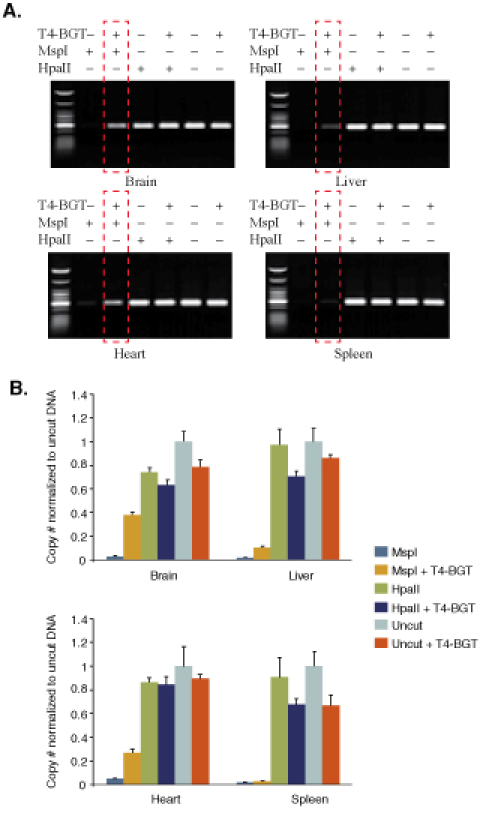

Figure 1.Comparison of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine amounts at locus 12 in different mouse Balb/C tissue samples. (A), End-point PCR. (B), Real time PCR.

Figure 1.Comparison of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine amounts at locus 12 in different mouse Balb/C tissue samples. (A), End-point PCR. (B), Real time PCR.

DNA from four mouse tissues was analyzed. For comparative purposes, real time PCR data were normalized to uncut DNA. A standard curve was used to determine copy number. The samples could be normalized by dividing the copy number of samples No 1-6 by the copy number of the control that is undigested (No 5). Boxed gel lane shows variation in 5-hmC present.

Discussion

There are several critical things to consider when setting up this experiment. First, it is important that the glucosylation of genomic DNA proceeds to completion. The sequence specificity of T4-BGT is not known, and it appears to have no choice for the substrate sequence. Therefore, in some cases, longer incubation times may be necessary. Second, MspI and HpaII digestion must be complete in order to avoid background signal. For these restriction enzymes, we recommend an incubation time of 4 hours, but longer incubations can be performed when incomplete cleavage is observed. Third, input DNA amount can be adjusted depending on availability, since 20 ngs of DNA can be used for end-point PCR. Finally, we recommend the use of supplied control DNA which may be run in parallel with genomic DNA for 5-mC and 5-hmC quantification.

Disclosures

Both Ted and Romas, authors of this article, are employees of NEB; Romas is the main developer of the kit, with Ted being the Director of the Applications & Development Department that oversaw the development of this kit.

Acknowledgments

Sriharsa Pradhan, Shannon Morey Kinney, Hang Gyeong Chin, Jurate Bitinaite, Yu Zheng, Pierre Olivier Esteve, Romualdas Vaisvila, Steven E. Jacobsen s laboratory, UCLA. This work was partially supported by NIH 1R44GM095209-01.

References

- Sadri R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4987–4989. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur EJ. Gene. 1991;108:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkus V, Petrauskiene L, Maneliene Z, Klimasaukas S, Laucys V, Janulaitis A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7091–7102. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Lyer LM, Liu DR. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pastor WA, Shen Y, Tahiliani M, Liu DR, Rao A. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8888–e8888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]