The authors believe this study represents a major advance in the field in conjunctivochalasis to link the pathogenic role of TSG-6 in controlling transcription and activation of MMP-1 in the conjunctival tissue.

Abstract

Purpose.

To investigate the role of anti-inflammatory TSG-6 in controlling MMP-1 and MMP-3, which have been shown to be upregulated in conjunctivochalasis (CCh).

Methods.

Immunostaining of TSG-6 was compared between normal and CCh conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule. Second cultures of normal and CCh fibroblasts were transfected with or without TSG-6 siRNA and then with or without the addition of TNF-α or IL-1β. Cell lysates and culture media were collected to assess apoptosis with the use of ELISA and the expression of TSG-6, MMP-1, and MMP-3 transcripts and proteins with the use of qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively.

Results.

TSG-6 expression was constitutive in the in vivo normal conjunctival epithelium. Significantly more TSG-6–positive cells than normal specimens were noted in CCh subconjunctival tissue and Tenon's capsule. TSG-6 was constitutively expressed intracellularly by both resting normal and CCh fibroblasts but was secreted extracellularly only by resting CCh fibroblasts. Intracellular and extracellular TSG-6 proteins were markedly upregulated by TNF-α or IL-1β in normal and CCh fibroblasts. Active MMP-1 was found in CCh fibroblasts intracellularly and extracellularly, whereas only proMMP-1 was found intracellularly in normal fibroblasts. Knockdown by TSG-6 siRNA upregulated more MMP-1 than MMP-3 transcripts in normal and CCh fibroblasts. TSG-6 siRNA led to extracellular MMP-1 expression by normal fibroblasts such as CCh fibroblasts. This activation of MMP-1 was further enhanced by IL-1β. Cell apoptosis was higher in CCh fibroblasts and further aggravated by TSG-6 siRNA knockdown.

Conclusions.

TSG-6 exerts an anti-inflammatory function by counteracting the transcription of MMP-1 and MMP-3 and the activation of MMP-1. Dysfunction of TSG-6 might play a role in the pathogenesis of CCh.

Conjunctivochalasis (CCh), defined as a loose, redundant, and nonedematous bulbar conjunctiva interposed between the globe and the eyelid, is a frequently overlooked ocular surface problem in the aging population.1–3 Although initially asymptomatic, CCh eventually leads to dryness, tearing, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and exposure2–4 Tear levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1-β (IL-1β), IL-6, and IL-8 are elevated in CCh patients.5–7 The coexisting ocular surface inflammation might further be aggravated by delayed tear clearance, which is also frequently associated with CCh.8–10

We have long speculated that excessive proteolytic degradation by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) leads to CCh. In support of this hypothesis, we have reported that cultured CCh fibroblasts produce more MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts and proteins than normal conjunctival fibroblasts11 and that such overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 is further upregulated by TNF-α or IL-1β12 Others7 have also shown that a significantly higher number of conjunctival epithelial cells and stromal cells express MMP-3 and MMP-9 in CCh patients. Even if we assumed that CCh is a disease caused by the dysregulation of MMPs, it remains unclear whether MMP dysregulation is causatively linked to the patient's ability to manage ocular surface inflammation.

One such linkage might be TNF-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6), which is secreted by cultured human fibroblasts under the stimulation of TNF-α.13,14 TSG-6, a 35-kDa glycosaminoglycan-binding protein,15,16 is not expressed but is rapidly upregulated by TNF-α or IL-1 in most normal cells.13,14,16 TSG-6 exerts anti-inflammatory activities in experimental models of arthritis,17–19 acute myocardial infarction,20 and acute corneal chemical burn.21,22 One mechanism for TSG-6 to yield a chondroprotective effect in the arthritic process23 and to exert its anti-inflammatory action in rat corneas that have been chemically burned21 might be through the suppression of MMPs activation. Herein, we provide strong evidence supporting the notion that TSG-6 downregulates the transcription and activation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 as one key anti-inflammatory action in combating the development of CCh.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), Ham's/F12 medium, amphotericin B, gentamicin, fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, human epidermal growth factor, β-mercaptoethanol, 0.25% trypsin/1 mM EDTA (T/E), Hank's balanced salt solution, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), dispase II, collagenase A, and insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite supplement were obtained from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Hydrocortisone, dimethyl sulfoxide, cholera toxin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), Triton X-100, Hoechst 33342, β-actin, IL-1β, TNF-α, and anti–mouse IgG-FITC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mouse anti–human TSG-6 IgG and mouse anti–human pro/active MMP-1 and pro/active MMP-3 antibodies24 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Polyclonal rabbit anti–mouse immunoglobulins/HRP was purchased from Dako (Carpinteria, CA).

Human Conjunctival Fibroblast Cultures

Adherence to tenets of Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human or human tissue and under protocol 06-013 approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baptist Hospital of Miami/South Miami Hospital (Miami, FL), CCh specimens were obtained from four patients after surgical removal. Two CCh patients (a 60-year-old man and a 77-year-old woman) did not have any other ocular surface diseases. Two CCh patients (an 82-year-old man and a 60-year-old woman) also had aqueous tear-deficient dry eye that had been treated with punctal occlusion. Normal conjunctival specimens were obtained from the corneoscleral rims of five human cadaveric donors younger than age 40 (causes of death were accidental [trauma or drowning]) provided by the Florida Lions Eye Bank (Miami, FL). To remove epithelial sheets,25 both conjunctival specimens were digested with 10 mg/mL Dispase II at 4°C for 12 hours under 95% humidified 5% CO2 in plastic dishes containing the supplemented hormonal epithelial medium (SHEM), which was made of an equal volume of HEPES-buffered DMEM and Ham's F12 containing bicarbonate, 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 2 ng/mL mouse EGF, 5 μg/mL insulin, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 5 ng/mL sodium selenite, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 30 ng/mL cholera toxin, 5% FBS, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, and 1.25 μg/mL amphotericin B. The remaining subconjunctival stromal tissue was minced and digested with 1 mg/mL collagenase A in SHEM at 37°C for 12 hours under 95% humidified air/5% CO2. After centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes, cells released by collagenase were collected from the pellet and seeded at a density of 4.0 × 104 cells per 12-well plate in SHEM. On 80% to 90% confluence, fibroblasts were released by T/E and split at 1:4 to another 12-well plate in the same medium. Cell lysates from the secondary passage cultures were used in this study.

Cell Treatments

Secondary cultures at 90% confluence were switched to DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 hours. Some cultures were then added with 20 ng/mL TNF-α or IL-1β for 4 or 24 hours before they were harvested for total RNA or protein, respectively. Other cultures were transfected by 100 nM TSG-6 siRNA (SR304882A) or scrambled RNA (scRNA) (SR30004) (both from OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) for 48 hours. During the last 24 hours, cultures were treated with or without 20 ng/mL IL-1β.

Immunostaining

The conjunctival tissue and the underlying Tenon's capsule were separated from both normal and CCh specimens, cryosectioned to 6-μm thickness, and dried for 5 minutes before they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. The sections were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 to 30 minutes and blocked with 0.2% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature before incubation in the primary antibody against TSG-6 (1:100) overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibody (FITC- anti–mouse IgG (1:100) was then incubated for 1 hour using appropriate isotype-matched nonspecific IgG antibodies as controls.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted using an extraction kit (RNeasy Mini Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse-transcribed using a transcription kit (High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). cDNA of each sample was amplified by real-time RT-PCR using specific primer-probe mixtures and DNA polymerase in a PCR system (7000 Real-time PCR; Applied Biosystems). The real-time PCR profile consisted of 10 minutes of initial activation at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15-second denaturation at 95°C and 1 minute annealing and extension at 60°C. All assays were performed in triplicate; the results were normalized by glceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as an internal control. Relative gene expression data were analyzed by the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT). All gene expression assays used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Assay ID and Probe Sequence Use for Real-time PCR

| Gene | Assay ID | UniID | Product Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GADPH | Hs02758891_g1 | Hs.4279728 | 93 |

| TSG-6 | Hs01113602_ml | Hs.437322 | 81 |

| MMP-1 | Hs00899658_ml | Hs.83169 | 64 |

| MMP-3 | Hs00968305_ml | Hs.375129 | 126 |

Western Blot Analysis

To identify the expression of TSG-6, MMP-1, and MMP-3 proteins, Western blot analysis was performed using their specific antibodies. Total proteins of 20 μg (for TSG-6) or 35 μg (for MMP-1 and MMP-3) from cell lysates or 20 to 25 μL of concentrated culture media from different fibroblast cultures were separated by electrophoresis on 4% to 15% (wt/vol) gradient acrylamide ready gels under denaturing and reducing conditions. Proteins in gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was then blocked with 5% (wt/vol) fat-free milk in TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% [vol/vol] Tween-20), followed by sequential incubation with specific primary antibodies to TSG-6 (1:1000), pro/active MMP-1 (1:500), and pro/active MMP-3 (1:500) and the secondary antibody (rabbit anti–mouse immunoglobulins/HRP, 1:1000), using β-actin as the loading control. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with reagent (Western Lighting Chemiluminesence Reagent; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Cell Death Detection ELISA Assay

Culture media and cell lysates from 104 cells were collected and subjected to assay (Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS; Roche, Indianapolis, IN), which is a photometric enzyme immunoassay for in vitro qualitative and quantitative determination of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (mononucleosomes and oligonucleosomes) generated by apoptotic cell death using mouse monoclonal anti–histone and anti–DNA antibodies, respectively. Positive and negative controls were provided by the manufacturer. The activity was determined by absorbance measured at 405 nm (Fusion Universal Microplate Analyzer; Packard, Indianapolis, IN).

Statistical Analysis

All summary data were reported as mean ± SD for each group and compared using Student's unpaired t-test (Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Test results were reported as two-tailed P values, where P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

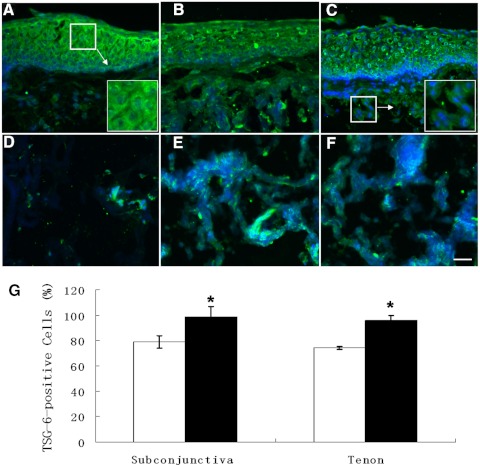

More TSG-6–Positive Cells in CCh Subconjunctival Tissue and Tenon's Capsule

Positive immunoreactive staining to TSG-6 was noted in the full thickness of the conjunctival epithelium of representative normal (Fig. 1A) and CCh (Figs. 1B, 1C) specimens. Little scattered positive staining to TSG-6 was also noted in normal (Fig. 1D) subconjunctival tissue and Tenon's capsule; however, more intensive positive staining was noted in CCh subconjunctival tissue (Figs. 1B, 1C) and Tenon's capsule (Figs. 1E, 1F). Higher magnification revealed that positive TSG-6 immunostaining was found in the cytoplasm and the extracellular matrix of both epithelia and fibroblasts (Figs. 1A, 1C, insets). The percentage of TSG-6–positive cells in CCh specimens was more than that in normal specimens (Fig. 1G; P < 0.01; n = 4). There was no difference between the subconjunctival tissue and the Tenon's capsule in either normal (P = 0.37; n = 4) or CCh (P = 0.20; n = 4) specimens. These findings were noted in all five cadaveric donors and four CCh specimens. These results further suggested that more TSG-6 protein was present intracellularly and extracellularly in CCh subconjunctival tissue and the Tenon's capsule.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of TSG-6 in normal and CCh conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule. One representative normal (A, D) and two representative CCh (B, C, E, F), conjunctival tissue (A, C), and Tenon's capsule (D–F) were subjected to immunofluorescence staining using a TSG-6–specific antibody. More positive immunostaining to TSG-6 was noted in CCh than in normal conjunctival stroma (B, C) and Tenon's capsule (E, F). Nuclear counterstaining was performed by Hoechst 33342. All images except those in the insets in (A) and (C) were taken at the same magnification. Scale bar, 50 μm. The percentage of TSG-6–positive cells in the subconjunctival tissue and the Tenon's capsule of normal (□) and CCh (■) samples (n = 4) were quantified and compared (G). *P < 0.01 versus normal.

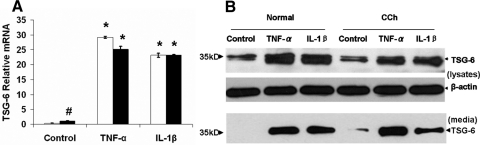

Upregulation of TSG-6 Transcripts and Proteins by TNF-α or IL-1β

TSG-6 is originally identified as cDNA derived from TNF-α–stimulated human fibroblasts13,14 and is expressed in a variety of cell types only after the stimulation of TNF-α, IL-1,13,14,16 or LPS26,27 or growth factors such as TGF-β, FGF, and FGF-1.28,29 To explore the immunostaining finding of TSG-6, we isolated both normal and CCh conjunctival fibroblasts. qRT-PCR confirmed that the TSG-6 transcript expressed by resting normal conjunctival fibroblasts was negligibly low but significantly (85- and 68-fold) upregulated by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively (Fig. 2A; both P < 0.01; n = 4). In contrast, the TSG-6 transcript expressed by resting CCh conjunctival fibroblasts was 3-fold higher than that of normal conjunctival fibroblasts (Fig. 2A; P < 0.01; n = 4). Similarly, the expression of TSG-6 transcript in CCh fibroblasts was upregulated 22- and 21-fold by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively (Fig. 2A; both P < 0.01; n = 4). Western blot analysis detected a similar intensity of the 35-kDa band of TSG-6 protein in cell lysates of both resting normal and CCh fibroblasts (Fig. 2B, top). The intensity increased 3.5- and 3-fold in normal fibroblasts but 1.7- and 1.8-fold in CCh fibroblasts by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively. The TSG-6 protein band was absent in culture media of resting normal fibroblasts but present in culture media of resting CCh fibroblasts (Fig. 2B, bottom). The protein level of TSG-6 in culture media was upregulated by TNF-α and IL-1β in normal and CCh fibroblasts. These results suggested that TSG-6 was constitutively expressed intracellularly in both resting normal and CCh fibroblasts but was secreted in culture media only by resting CCh fibroblasts. Expression and extracellular secretion of TSG-6 were upregulated by TNF-α or IL-1β in both normal and CCh fibroblasts.

Figure 2.

Upregulation of TSG-6 transcripts and proteins by TNF-α or IL-1β in normal and CCh fibroblasts. Both normal (□) and CCh (■) fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 hour before the addition of TNF-α or IL-1β. Cell lysates were collected at 4 hours to measure TSG-6 transcripts by qRT-PCR using GAPDH as the internal control (A, #P < 0.01 vs. normal; *P < 0.01 vs. control). Cell lysates (B, top) and culture media (B, bottom) were collected at 24 hours to measure TSG-6 protein by Western blot analysis using β-actin as the loading control.

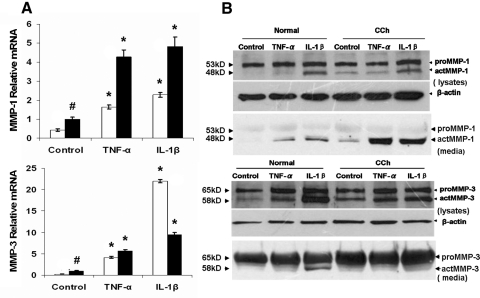

Upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 Transcripts and Activation of MMP-1 by TNF-α and IL-1β

Previously, we reported the overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts in CCh fibroblasts using Northern blot analysis.11 Herein, qRT-PCR confirmed that resting CCh fibroblasts expressed MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts 2- and 4-fold those expressed by resting normal fibroblasts (Fig. 3A; both P < 0.01; n = 4). Consistent with our report that TNF-α and IL-1β upregulate MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts and proteins in CCh fibroblasts,12 we also noted that MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts were upregulated 3- and 18-fold in normal fibroblasts by TNF-α and 5- and 95-fold by IL-1β, respectively (all P < 0.01; n = 4). A similar upregulation of 4- and 6-fold by TNF-α and 5- and 10-fold by IL-1β, respectively, was noted in CCh fibroblasts (all P < 0.01; n = 4). Although the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 proteins by CCh fibroblasts were further promoted by TNF-α or IL-1β,12 it remained unclear whether elevated MMP-1 and MMP-3 proteins were active. Using different primary antibodies that recognize both proMMPs and actMMPs, Western blot analysis revealed two protein bands. For MMP-1 they were 53 kDa proMMP-1 and 48 kDa actMMP-1, and for MMP-3 they were 65 kDa proMMP-3 and 58 kDa actMMP-3 (Fig. 3B) in both cell lysates and culture media. In cell lysates, the intensity of the proMMP-1 protein was similar in resting normal and CCh fibroblasts but was upregulated 1.5- and 2-fold in normal fibroblasts by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively, and 2.2-fold in CCh fibroblasts by IL-1β. In contrast, the actMMP-1 protein was undetectable in normal fibroblasts but upregulated 4-fold in resting CCh fibroblasts. The actMMP-1 protein was upregulated 2.5- and 8.4-fold in normal fibroblasts and 4- and 8-fold in CCh fibroblasts by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively. In culture media, proMMP-1 proteins were similar in both normal and CCh fibroblasts regardless of whether cytokine stimulation occurred. In contrast, actMMP-1 was detected in resting CCh but not in normal fibroblasts and was upregulated to the detectable level in normal fibroblasts and 6-fold in CCh fibroblasts by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively. In cell lysates, the intensity of the proMMP-3 protein band was similar before stimulation but similarly upregulated 2-fold by either TNF-α or IL-1β in normal and CCh fibroblasts. The actMMP-3 protein band was present in resting normal fibroblasts but increased 2.5-fold in resting CCh fibroblasts. The intensity of the actMMP-3 protein band was upregulated 3- and 8.8-fold in normal fibroblasts and 4.5- and 6-fold in CCh fibroblasts by TNF-α and IL-1β, respectively. In culture media, the intensity of the proMMP-3 protein band was also similar between normal and CCh fibroblasts and was not upregulated by either TNF-α or IL-1β. actMMP-3 was slightly upregulated by IL-1β. These results indicated that resting CCh fibroblasts expressed more MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts and actMMP-1 proteins than resting normal fibroblasts. On stimulation by TNF-α and IL-1β, both MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts and actMMP-1 protein were upregulated in normal and CCh fibroblasts.

Figure 3.

Upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts and proteins by TNF-α or IL-1β in normal and CCh fibroblasts. In the same cultures as described in Figure 2, expression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts in normal fibroblasts (□) and CCh fibroblasts (■) was detected by qRT-PCR (A, #P < 0.01 vs. normal; *P < 0.01 vs. control). Both proMMP-1 and actMMP-1 (top) and proMMP-3 and actMMP-3proteins (bottom) in cell lysates and culture media were monitored by Western blot analysis (B).

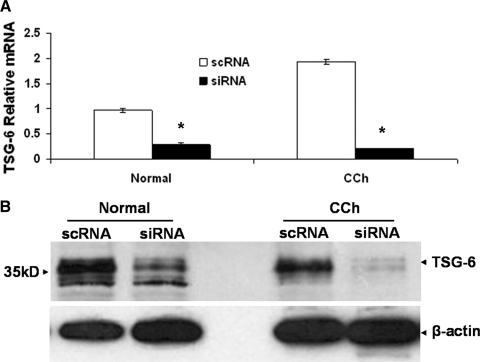

Upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 Transcription and Activation by TSG-6 Knockdown

Because transcripts and proteins of MMP-1, MMP-3, and TSG-6 were all upregulated by TNF-α and IL-1β (Figs. 2, 3), we thus chose TSG-6 siRNA to downregulate TSG-6 transcript and protein expression to resolve the relationship between MMPs and TSG-6. qRT-PCR verified that the chosen TSG-6 siRNA indeed downregulated 70% and 88% of the transcript level expressed by normal and CCh fibroblasts, respectively (Fig. 4A). Western blot analysis also confirmed that TSG-6 protein expression was downregulated 75% and 84% by TSG-6 siRNA in normal and CCh fibroblasts, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Knockdown efficiency of TSG-6 siRNA. Both normal and CCh fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 hours before transfection with 100 nM TSG-6 siRNA or scRNA for another 48 hours. qRT-PCR showed that the TSG-6 transcript was markedly downregulated using GAPDH as the internal control (A, *P < 0.01 vs. scRNA). Western blot analysis also showed that the TSG-6 protein was notably downregulated using β-actin as the loading control (B).

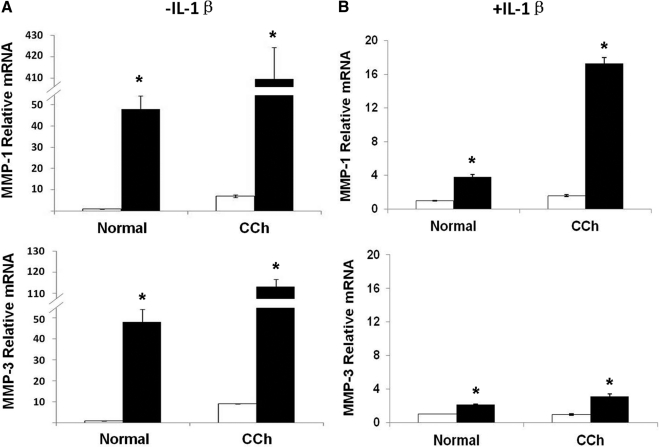

Without stimulation by IL-1β, and similar to what is shown in Figure 3A, the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts by resting CCh fibroblasts treated with scRNA were greater (7- and 9-fold) than the expression of resting normal fibroblasts (Fig. 5A; both P < 0.01; n = 4). TSG-6 siRNA significantly upregulated MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts 52- and 52-fold in normal fibroblasts and 58- and 13-fold in CCh fibroblasts (Fig. 5A; all P < 0.01; n = 4). The overall extent of upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts by TSG-6 siRNA was more pronounced in CCh fibroblasts than normal fibroblasts (P < 0.01; n = 4). With stimulation by IL-1β and as shown in Figure 3A, the expression of MMP-1 transcripts in CCh fibroblasts was higher than in normal fibroblasts (Fig. 5B; P < 0.05; n = 4), whereas the expression of MMP-3 transcripts was similar in both cells (P = 0.12; n = 4) when treated with scRNA. Both MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts expressed by normal fibroblasts were further upregulated 4- and 4-fold, respectively, by TSG-6 siRNA (both P < 0.01; n = 4). As a comparison, MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts in CCh fibroblasts were upregulated 11- and 3-fold, respectively, by TSG-6 siRNA (both P < 0.01; n = 4).

Figure 5.

Upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts in normal and CCh fibroblasts by TSG-6 knockdown. Both normal and CCh fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 hours and were transfected with TSG-6 scRNA (□) or siRNA (■) for another 48 hours without (A) or with (B) IL-1β added for the last 24 hours. Cell lysates were collected for MMP-1 and MMP-3 mRNA detection by qRT-PCR. *P < 0.01 versus scRNA.

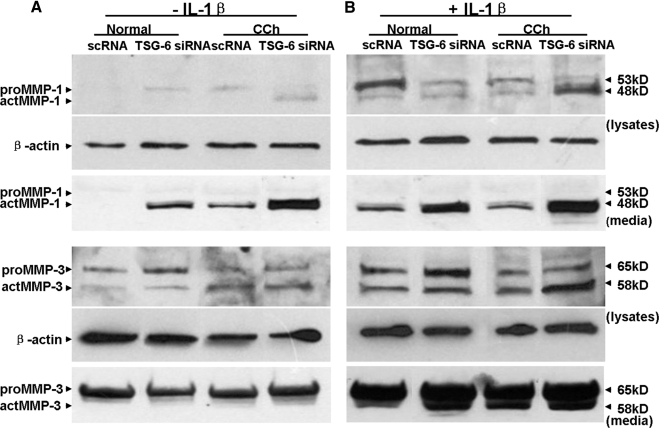

Without stimulation by IL-1β and as shown in Figure 3B, neither proMMP-1 nor actMMP-1 was present in cell lysates and culture media of normal fibroblasts. In contrast, proMMP-1 protein was found in cell lysates, whereas actMMP-1 protein was found in culture media of CCh fibroblasts (Fig. 6A). TSG-6 siRNA induced proMMP-1 protein in cell lysates and actMMP-1 proteins in culture media of normal fibroblasts, a pattern resembling that of CCh fibroblasts treated with scRNA. In contrast, TSG-6 siRNA induced actMMP-1 in cell lysates and upregulated actMMP-1 in culture media of CCh fibroblasts. As shown in Figure 3B, proMMP-3 and actMMP-3 were expressed in cell lysates by resting normal and CCh fibroblasts treated with scRNA, but actMMP-3 expressed by resting CCh fibroblasts was 2.6-fold that of normal fibroblasts (Fig. 6A). TSG-6 siRNA increased actMMP-3 by 2- and 3-fold in normal fibroblasts and CCh fibroblasts, respectively. However, proMMP-3, but not actMMP-3, was found in culture media of both normal and CCh fibroblasts.

Figure 6.

Upregulation of MMP-1 and MMP-3 protein and actMMP-1 by TSG-6 knockdown. In the same cultures described in Figure 4, cell lysates were collected for Western blot analysis of proMMP1and actMMP-1 proteins (top) and MMP-3 proteins (bottom) in cell lysates and culture media of both normal and CCh fibroblasts without (A) and with (B) stimulation of IL-1β using β-actin as the loading control.

With stimulation by IL-1β and as shown in Figure 3B, actMMP-1 was found in both cell lysates and culture media of normal and CCh fibroblasts treated by scRNA (Fig. 6B). However, TSG-6 siRNA further upregulated actMMP-1 8-fold in cell lysates of CCh but not normal fibroblasts, and it upregulated actMMP-1 3- and 5.2-fold in culture media of normal and CCh fibroblasts, respectively. Consistent with what is shown in Figure 3B, IL-1β increased actMMP-3 in both cell lysates and culture media of resting normal and CCh fibroblasts; the level of actMMP-3 was increased 2-fold by TSG-6 siRNA in normal and CCh fibroblasts, respectively. Taken together, these findings indicated that knockdown by TSG-6 siRNA upregulated more MMP-1 than MMP-3 transcripts in normal and CCh fibroblasts. Without IL-1β, TSG-6 knockdown activated MMP-1 protein expression in normal fibroblasts in a direction resembling CCh fibroblasts. Such activation of MMP-1 was further enhanced by IL-1β.

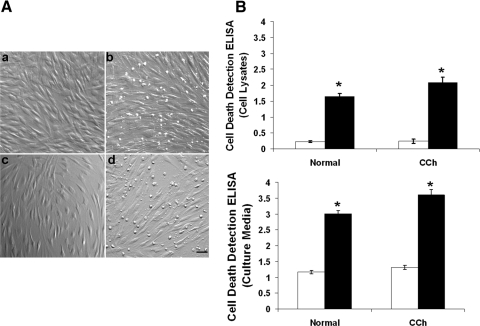

Cell Apoptosis Promoted by TSG-6 Knockdown

Interestingly, many small round and detached cells appeared as early as 24 h and became apparent approximately 36 hours after transfection by TSG-6 siRNA in normal and CCh fibroblast cultures (Fig. 7A). This morphologic change was correlated with apoptosis, as judged by cell death detection ELISA (Fig. 7B). In short, the extent of cell apoptosis in cell lysates was low in both normal and CCh fibroblasts (P = 0.052; n = 3) but increased 4- and 5-fold in normal and CCh fibroblasts by TSG-6 siRNA, respectively (both P < 0.01; n = 3). Apoptosis in cell lysates caused by TSG-6 siRNA in CCh fibroblasts was significantly greater than in normal fibroblasts (P < 0.05; n = 3). A similar result was noted in culture media (Fig. 7B). Compared with cells treated with scRNA, the extent of cell necrosis in culture media of CCh fibroblasts was higher than that of normal fibroblasts (P < 0.05; n = 3). TSG-6 siRNA further promoted the extent of cell necrosis to 2.5- and 2.7-fold in normal and CCh fibroblasts, respectively (both P < 0.01, n = 3); the extent of cell necrosis in CCh fibroblasts was significantly higher than that in normal fibroblasts (P < 0.05; n = 3). These results indicated that CCh fibroblasts exhibited higher apoptosis than normal fibroblasts and that such apoptosis was further promoted by TSG-6 knockdown.

Figure 7.

Apoptosis promoted by TSG-6 knockdown. Both normal and CCh fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 48 hours and were transfected with TSG-6 siRNA for another 48 hours while IL-1β was added for the last 24 hours. (A) Compared with the control treated with scRNA (a, normal fibroblasts; c, CCh fibroblasts), TSG-6 siRNA caused more detached round cells in normal (b) and CCh fibroblasts (d). All images were taken at the same magnification. Scale bar, 100 μm. Compared with scRNA (□), the extent of cell apoptosis was also significantly increased by TSG-6 siRNA (■) (*P < 0.01) in cell lysates (B, top) and in culture media (B, bottom) in normal and CCh fibroblasts.

Discussion

Generally speaking, TSG-6 is not constitutively expressed in most tissues, but it is upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines in a variety of cells, including articular chondrocytes,30 synoviocytes,31 cervical smooth muscle cells,32 peripheral blood mononuclear cells,14 and myeloid dendritic cells.33 A high level of TSG-6 protein is detected in the sera of patients who have bacterial sepsis and systemic lupus erythematosus16 and in joint tissues and synovial fluids of patients with various forms of arthritis.31,34 Thus, the finding of more TSG-6–positive cells in CCh subconjunctival stroma and Tenon's capsule than cadaveric donors (Fig. 1) supported the notion that TSG-6 might exert an anti-inflammatory role in CCh, as claimed in other tissues. The overexpression of TSG-6 in CCh subconjunctival stroma and Tenon's capsule was consistent with the finding of a higher expression of TSG-6 transcript by resting CCh fibroblasts than normal fibroblasts (Fig. 2A) and a higher expression of TSG-6 protein in culture media of resting CCh fibroblasts (Fig. 2B). Because TSG-6 transcript and protein were further upregulated by TNF-α and IL-1β (Fig. 2B), and because there exists a higher level of proinflammatory cytokines in the tear meniscus of CCh patients,5,7 it is plausible that ocular surface inflammation might be upregulated TSG-6 in CCh.

We have long speculated that excessive degradation of the underlying Tenon's capsule in CCh35,36 is caused by the overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3.11,12 MMP-1, also known as interstitial collagenase, can cleave the triple helix of fibrillar collagens I, II, and III. MMP-3, also known as stromelysin-1, has a broader substrate specificity of degrading collagens III, IV, IX, and X, laminin, proteoglycans, and fibronectin.37The present study supported our earlier finding that MMP-1 and MMP-3 transcripts and proteins are overexpressed by CCh fibroblasts. However, for the first time, we showed that actMMP-1 was found in cell lysates and culture media of resting CCh fibroblasts, whereas only proMMP-1 was found in cell lysates of resting normal fibroblasts (Fig. 3). Both actMMP-1 and actMMP-3 were further upregulated by TNF-α or IL-1β in normal and CCh fibroblasts. As a contrast to resting normal conjunctival fibroblasts, actMMP-1 was upregulated only by TNF-α and IL-1β in resting CCh fibroblasts (Figs. 3, 6). These data suggest that proteolytic degradation of matrix by actMMP-1 is intrinsically upregulated in CCh fibroblasts but only upregulated in normal fibroblasts by proinflammatory cytokines.

TSG-6 (Fig. 2), MMP-1, and MMP-3 (Fig. 3) were all upregulated by TNF-α and IL-1β in both normal and CCh fibroblasts, suggesting that these three genes were all under the regulation of inflammation. In U373MG cells, the overexpression of C/EBPδ, a transcription factor downstream of NF-κB,38 also upregulates the transcription of TSG-6, MMP-1, and MMP-3.39 To resolve the causative relationship between TSG-6 and MMP-1/MMP-3, we used TSG-6 siRNA to downregulate its transcript and protein (Fig. 4) and disclosed for the first time that one plausible mechanism explaining how MMP-1 is activated in CCh fibroblasts might be the dysregulation of TSG-6. In the absence of IL-1β, TSG-6 siRNA dramatically upregulated the expression of MMP-1 transcript more so than MMP-3 transcript (Fig. 6) and enhanced the expression of proMMP-1 in cell lysates and actMMP-1 in culture media of normal fibroblasts (Fig. 6), resulting in an expression pattern resembling that of resting CCh (Fig. 3). In the presence of IL-1β, these changes were more accentuated. These findings strongly suggest that the expression of TSG-6 is meant to counteract the transcription and activation of MMP-1 particularly. Such an action resembles the anti-inflammatory role of TSG-6 in suppressing MMP-9 activation in rat chemically burned corneas21 and its chondroprotective role in suppressing MMP activation in the arthritic joint of TSG-6 transgenic mice.23 In the experimental models of arthritis17,19 and corneal chemical burns,21,22 the protective role of TSG-6 is demonstrated by transgenic overexpression and exogenous application of TSG-6 (i.e., through an extracellular route). The likelihood for extracellular TSG-6 to exert its anti-inflammatory action is also suggested by its in vivo constitutive extracellular expression in the normal conjunctival epithelium (Fig. 1) and the extracellular expression of TSG-6 only by CCh fibroblasts (Fig. 2). Hence, the pathogenesis of CCh might involve the dysregulation of TSG-6 expression. Further studies are worthwhile to determine how MMP-1 is activated in CCh fibroblasts and whether the activation of MMP-1 in CCh fibroblasts is mediated by the overproduction of reactive oxygen species or serine proteinases known to activate MMP-140 and how TSG-6 might control such an activation process.

Extracellular MMP-1 and MMP-3 may conceivably cause anoikis by threatening cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix. However, the present study further showed that elevated levels of actMMP-1 and actMMP-3 were noted intracellularly in both normal and CCh fibroblasts, especially if stimulated by IL-1β (Fig. 3). Because the overexpression of intracellular actMMP-1 and actMMP3 was also correlated with apoptosis exacerbated by TSG-6 siRNA (Fig. 7) and because more apoptotic cells were also found in CCh specimens (Guo et al., manuscript submitted), we cannot rule out the likelihood that such overexpression of intracellular actMMP-1 and actMMP-3 might cause apoptosis. Such reasoning is supported by recent studies41,42 showing that intracellular actMMP-1 is responsible for cell death of cultured neurons and myocytes cells and that intracellular actMMP-3 is also responsible for causing apoptosis, including in DArgic neurons and hepatic myofibroblasts.24,43,44 Further studies focusing on the protective role of TSG-6 in combating MMP activities and cell death may shed light on the pathogenesis of CCh, which is highlighted by excessive degradation of the underlying Tenon's capsule.

Footnotes

Supported by National Eye Institute/National Institutes of Health Research Grants EY017497 and EY021045, a research grant from TissueTech, Inc., an unrestricted grant from Ocular Surface Research & Education Foundation, and Shenzhen Science and Technology Bureau Research Grant 201102187.

Disclosure: P. Guo, None; S.-Z. Zhang, None; H. He, None; TissueTech, Inc. (E); Y.-T. Zhu, None; TissueTech, Inc. (E); S.C.G. Tseng, TissueTech, Inc. (I), P

References

- 1. Meller D, Tseng SC. Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43:225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Di Pascuale MA, Espana EM, Kawakita T, Tseng SC. Clinical characteristics of conjunctivochalasis with or without aqueous tear deficiency. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:388–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yokoi N, Komuro A, Nishii M, et al. Clinical impact of conjunctivochalasis on the ocular surface. Cornea. 2005;24:S24–S31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mimura T, Usui T, Yamagami S, et al. Subconjunctival hemorrhage and conjunctivochalasis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1880–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Acera A, Rocha G, Vecino E, Lema I, Duran JA. Inflammatory markers in the tears of patients with ocular surface disease. Ophthalmic Res. 2008;40:315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Erdogan-Poyraz C, Mocan MC, Bozkurt B, Gariboglu S, Irkec M, Orhan M. Elevated tear interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 levels in patients with conjunctivochalasis 1. Cornea. 2009;28:189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ward SK, Wakamatsu TH, Dogru M, et al. The role of oxidative stress and inflammation in conjunctivochalasis 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1994–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prabhasawat P, Tseng SCG. Frequent association of delayed tear clearance in ocular irritation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:666–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y, Dogru M, Matsumoto Y, et al. The impact of nasal conjunctivochalasis on tear functions and ocular surface findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:930–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maskin SL. Effect of ocular surface reconstruction by using amniotic membrane transplant for symptomatic conjunctivochalasis on fluorescein clearance test results. Cornea. 2008;27:644–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li D-Q, Meller D, Tseng SCG. Overexpression of collagenase (MMP-1) and stromelysin (MMP-3) by cultured conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:404–410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meller D, Li D-Q, Tseng SCG. Regulation of collagenase, stromelysin, and gelatinase B in human conjunctival and conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts by interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2922–2929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee TH, Lee GW, Ziff EB, Vilcek J. Isolation and characterization of eight tumor necrosis factor-induced gene sequences from human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1982–1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee TH, Wisniewski H-G, Vilcek J. A novel secretory tumor necrosis factor-inducible protein (TSG-6) is a member of the family of hyaluronate binding protein, closely related to the adhesion receptor CD44. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:545–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee TH, Klampfer L, Shows TB, Vilcek J. Transcriptional regulation of TSG6, a tumor necrosis factor- and interleukin-1-inducible primary response gene coding for a secreted hyaluronan-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6154–6160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wisniewski HG, Vilcek J. TSG-6: an IL-1/TNF-inducible protein with anti-inflammatory activity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:143–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mindrescu C, Thorbecke GJ, Klein MJ, Vilcek J, Wisniewski HG. Amelioration of collagen-induced arthritis in DBA/1J mice by recombinant TSG-6, a tumor necrosis factor/interleukin-1-inducible protein. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2668–2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mindrescu C, Dias AA, Olszewski RJ, Klein MJ, Reis LF, Wisniewski HG. Reduced susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis in DBA/1J mice expressing the TSG-6 transgene. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2453–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bardos T, Kamath RV, Mikecz K, Glant TT. Anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effect of TSG-6 (tumor necrosis factor-alpha-stimulated gene-6) in murine models of experimental arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1711–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oh JY, Roddy GW, Choi H, et al. Anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6 reduces inflammatory damage to the cornea following chemical and mechanical injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16875–16880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roddy GW, Oh JY, Lee RH, et al. Action at a distance: systemically administered adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs) reduce inflammatory damage to the cornea without engraftment and primarily by secretion of TSG-6. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1572–1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glant TT, Kamath RV, Bardos T, et al. Cartilage-specific constitutive expression of TSG-6 protein (product of tumor necrosis factor alpha-stimulated gene 6) provides a chondroprotective, but not antiinflammatory, effect in antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2207–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi DH, Kim EM, Son HJ, et al. A novel intracellular role of matrix metalloproteinase-3 during apoptosis of dopaminergic cells. J Neurochem. 2008;106:405–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Espana EM, Romano AC, Kawakita T, Di Pascuale M, Smiddy R, Tseng SC. Novel enzymatic isolation of an entire viable human limbal epithelial sheet. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4275–4281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fessler MB, Malcolm KC, Duncan MW, Worthen GS. A genomic and proteomic analysis of activation of the human neutrophil by lipopolysaccharide and its mediation by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31291–31302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Malcolm KC, Arndt PG, Manos EJ, Jones DA, Worthen GS. Microarray analysis of lipopolysaccharide-treated human neutrophils. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L663–L670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feng P, Liau G. Identification of a novel serum and growth factor-inducible gene in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ye L, Mora R, Akhayani N, Haudenschild CC, Liau G. Growth factor and cytokine-regulated hyaluronan-binding protein TSG-6 is localized to the injury-induced rat neointima and confers enhanced growth in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1997;81:289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Margerie D, Flechtenmacher J, Buttner FH, et al. Complexity of IL-1 beta induced gene expression pattern in human articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5:129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wisniewski H-G, Maier R, Lotz M, Klampfer L, Lee TH, Vilcek J. TSG-6: a TNF-, IL-1-, and LPS-inducible secreted glycoprotein associated with arthritis. J Immunol. 1993;151:6593–6601 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fujimoto T, Savani RC, Watari M, Day AJ, Strauss JF., III Induction of the hyaluronic acid-binding protein, tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6, in cervical smooth muscle cells by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and prostaglandin E(2). Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1495–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le NF, Hohenkirk L, Grolleau A, et al. Profiling changes in gene expression during differentiation and maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells using both oligonucleotide microarrays and proteomics. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17920–17931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bayliss MT, Howat SL, Dudhia J, et al. Up-regulation and differential expression of the hyaluronan-binding protein TSG-6 in cartilage and synovium in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kheirkhah A, Casas V, Blanco G, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation with fibrin glue for conjunctivochalasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:311–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kheirkhah A, Casas V, Esquenazi S, et al. New surgical approach for superior conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2007;26:685–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murphy G, Docherty AJP. The matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:120–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Litvak V, Ramsey SA, Rust AG, et al. Function of C/EBPdelta in a regulatory circuit that discriminates between transient and persistent TLR4-induced signals. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:437–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ko CY, Chang LH, Lee YC, et al. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein delta (CEBPD) elevating PTX3 expression inhibits macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of dying neuron cells. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:422.e11–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kar S, Subbaram S, Carrico PM, Melendez JA. Redox-control of matrix metalloproteinase-1: a critical link between free radicals, matrix remodeling and degenerative disease. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174:299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vos CM, Sjulson L, Nath A, et al. Cytotoxicity by matrix metalloprotease-1 in organotypic spinal cord and dissociated neuronal cultures. Exp Neurol. 2000;163:324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen H, Li D, Saldeen T, Mehta JL. TGF-beta 1 attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibition of upregulation of MMP-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1612–H1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Si-Tayeb K, Monvoisin A, Mazzocco C, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 3 is present in the cell nucleus and is involved in apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1390–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim EM, Shin EJ, Choi JH, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-3 is increased and participates in neuronal apoptotic signaling downstream of caspase-12 during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16444–16452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]