Background: CHFR is a tumor suppressor that arrests the cell cycle at prophase.

Results: CHFR regulates the mitotic checkpoint via PARP-1 ubiquitination and degradation.

Conclusion: The interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 plays an important role in cell cycle regulation and cancer therapy.

Significance: Our data shed new light on a potential strategy for the combined usage of PARP inhibitors with microtubule inhibitors.

Keywords: Cancer Therapy, Cell Cycle, Checkpoint Control, E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Tumor Suppressor Gene, CHFR, PARP Inhibitor, PARP-1

Abstract

The mitotic checkpoint gene CHFR (checkpoint with forkhead-associated (FHA) and RING finger domains) is silenced by promoter hypermethylation or mutated in various human cancers, suggesting that CHFR is an important tumor suppressor. Recent studies have reported that CHFR functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, resulting in the degradation of target proteins. To better understand how CHFR suppresses cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis, we sought to identify CHFR-interacting proteins using affinity purification combined with mass spectrometry. Here we show poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) to be a novel CHFR-interacting protein. In CHFR-expressing cells, mitotic stress induced the autoPARylation of PARP-1, resulting in an enhanced interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 and an increase in the polyubiquitination/degradation of PARP-1. The decrease in PARP-1 protein levels promoted cell cycle arrest at prophase, supporting that the cells expressing CHFR were resistant to microtubule inhibitors. In contrast, in CHFR-silenced cells, polyubiquitination was not induced in response to mitotic stress. Thus, PARP-1 protein levels did not decrease, and cells progressed into mitosis under mitotic stress, suggesting that CHFR-silenced cancer cells were sensitized to microtubule inhibitors. Furthermore, we found that cells from Chfr knockout mice and CHFR-silenced primary gastric cancer tissues expressed higher levels of PARP-1 protein, strongly supporting our data that the interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 plays an important role in cell cycle regulation and cancer therapeutic strategies. On the basis of our studies, we demonstrate a significant advantage for use of combinational chemotherapy with PARP inhibitors for cancer cells resistant to microtubule inhibitors.

Introduction

The checkpoint with forkhead-associated (FHA)2 and RING finger domains (CHFR) gene is frequently inactivated by promoter hypermethylation in various human malignancies. Chfr-deficient mice are cancer-prone (1), suggesting that the CHFR protein functions as a tumor suppressor (2, 3). CHFR is a nuclear protein and plays an important role in the early mitotic checkpoint by actively delaying passage into mitosis in response to mitotic stress caused by microtubule inhibitors (4). However, it is not fully understood how CHFR acts in the mitotic checkpoint or how it is regulated in response to mitotic stress. CHFR contains an N-terminal FHA domain, a central RING finger domain, and a C-terminal cysteine-rich (CR) region. The FHA domain is required for the mitotic checkpoint (4). Additionally, we have reported previously that the FHA domain is required for the inhibition of NF-κB signaling (5). The RING finger domain of CHFR mediates its function as an E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligase, and CHFR catalyzes the synthesis of lysine 48 (Lys-48)-linked and lysine 63 (Lys-63)-linked polyubiquitination chains, which promote target protein degradation and alter protein function, respectively (6–8). Recently, a novel poly(ADP-ribose)-binding zinc finger (PBZ) motif was identified in the CR region of CHFR (9).

Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) is a posttranscriptional modification whereby poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) polymerize poly(ADP-ribose) onto acceptor proteins using NAD+ as a substrate. PARP-1, the most abundant and founding member of the PARP family, is activated by a DNA strand break, PARylates acceptor proteins, and automodifies PARP-1 itself. PARP-1 also initiates multiple cellular responses, including DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoint control, apoptosis, and transcription in the nucleus (10). In human cancers, the overexpression of PARP-1 has been reported in various human malignancies (11–15), indicating that deregulation of PARP-1 expression correlates with tumor development. Additionally, recent studies have suggested that PARP inhibitors could be used as anticancer drugs (16). However, the molecular mechanisms through which the deregulation of PARP-1 occurs or contributes to tumor development remain unclear. Furthermore, how PARP inhibitors exert their beneficial effects in tumor cells has not been established.

In this study, we identified PARP-1 as a novel CHFR binding protein and found a functional interaction that regulates the early mitotic checkpoint and tumorigenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfections

Human breast cancer cells (SK-BR-3 and ZR-75–1), human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa), human colorectal cancer cells (HCT116 and DLD-1), human stomach cancer cells (HSC-44, MKN7, and MKN45), human oral squamous cells (HSC-3), human non-small cell lung cancer cells (LU99), and human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293) used in this study were purchased from the ATCC or the Japan Collection of Research Bioresources. DLD-1 Tet-Off cells were double-transfected with regulatory pTet-Off (Clontech,) and responsive pTRE2-FLAG-CHFR or pTRE-pur control plasmids. HCT116 cells were transfected with iLenti-GFP PARP1 siRNAs or iLenti-GFP control plasmids (ABM). Colonies of cells stably transfected with iLenti-GFP PARP1 siRNA and iLenti-GFP were selected with G418, screened by immunoblotting, and named HCT116 siPARP1 and HCT116 siControl cells, respectively. All transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Generation of Chfr Knockout Mice and MEFs

The Chfr knockout mice were generated as a standard knockout project (project ID no. OYC056) by Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (supplemental Fig. S1 and methods). Briefly, the targeting vector was electroporated into Lex-1 ES cells derived from the 129SvEvBrd strain, and screened ES cell clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Chimeric mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 females or males at least seven times. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. The Chfr+/− mice were mated, and littermate primary MEFs were isolated from E14.5 mouse embryos and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum.

Plasmids, siRNAs and Recombinant Adenoviruses

The expression plasmid vectors for cDNAs encoding full-length CHFR and deletion constructs, and the corresponding adenoviruses have been reported previously (5). The CHFR ΔE3 mutant, lacking amino acids 292 to 309, and the ΔPBZ mutant, lacking amino acids 619 to 644, were inserted into a FLAG-tagged pCMV-tag2B vector (Stratagene). The expression vectors for cDNAs encoding full-length PARP-1 and deletion constructs have been reported previously (17). The pCI-neo-2S-ubiquitin plasmid expressing human ubiquitin was kindly provided by Dr. Hideyoshi Yokosawa of Hokkaido University, Japan. iLenti-GFP siRNA and iLenti-GFP PARP1 siRNA, which contain the oligonucleotide 5′-GTGAAGAAGCTGACAGTAAATCCTGGCAC-3′, were designed and purchased from ABM. The siRNAs targeting human PARP1 (5′-GAAAACAGGUAUUGGAUAU-3′, 5′-GUGUCAAAGGUUUGGGCAA-3′ and 5′-CAUGGGAGCUCUUGAAAUA-3′), AURKA (5′-UGUCAUUCGAAGAGAGUUATT-3′, 5′-CCAUAUAACCUGACAGGAATT-3′, and 5′-AGUCAUAGCAUGUGUGUAATT) and the control siRNAs were purchased from B-Bridge. The siRNA targeting human PLK1 (5′-rGUrCUrCrArArGrGrCrCUrCrCUrArAUrATT-3′) was purchased from Sigma (RNA nucleotides were indicated as “rN”).

Antibodies

The antibodies used for experiments were as follows: anti-FLAG antibody (M2, Sigma), anti-CHFR antibodies (PAB6325 and 1H3-A12, Abnova; 12169-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-PARP-1 antibodies (C2–10, BD Biosciences; catalog no. 611038, BD Biosciences; H-250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. 9542, Cell Signaling Technology; ALX-210–619, Enzo Life Science), anti-ubiquitin antibody (P4D1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-PAR antibodies (10H, Tulip BioLabs; catalog no. 4336-APC-050, Trevigen), anti-Plk-1 antibody (catalog no. 33–1700, Zymed Laboratories Inc.), anti-GFP antibody (sc-8334, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-actin antibody (MAB1501R, Millipore) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Co-immunoprecipitation Assays

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed as previously described (5). In brief, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in HBST buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 μm MG132 and protease inhibitor mixture). For endogenous binding analysis, the nuclear extracts were isolated and diluted 5-fold with HBST. The lysates were co-immunoprecipitated with antibodies.

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

The analysis of proteins by LC-MS/MS was performed as previously reported (14).

In Vitro Protein-Protein Binding Assays

Full-length or deletion mutants of biotinylated PARP-1 were generated by in vitro translation as previously reported (17). HEK-293T cells were mock transfected or transfected with Flag-CHFR expression vectors, and the Flag-CHFR protein was purified using an anti-Flag M2 antibody. The immunoprecipitants were incubated with in vitro translated PARP-1 proteins at 4 °C overnight in HBST buffer. The complexes were washed three times with HBST buffer, eluted by incubation for 1 h at 4 °C with 150 ng/μl of 3x Flag peptide (SIGMA) and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays

HEK-293T cells were mock-transfected or transfected with Myc-CHFR expression vectors. The cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm NaV, 10 mm NaF, 1 mm DTT, and protease inhibitor mixture). The Myc-CHFR and PARP-1 complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc resins. The resin was washed three times with lysis buffer and incubated with 0.03 μg/μl of FLAG-Ub, 8.3 ng/μl of E1 and 500 nm E2 (UbcH5c or Ube2N) in the reaction mixture (50 mm Tris-HCL (pH 7.4) 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm DTT and 5 mm ATP) for 30 min at 37 °C. The supernatants from the reactions were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting.

RT-PCR

For RT-PCR analysis, cDNAs were synthesized from 5 μg of total mouse RNA with SuperScript III (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions included an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 28 cycles (for Parp1), 27 cycles (for Chfr) or 21 cycles (for Gapdh) at 94 °C for 30 s, 63 °C (for Parp1), 61 °C (for Chfr) or 55 °C (for Gapdh) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min. Oligonucleotide primer sequences were as follows: Parp1 sense (5′-GACAGCGTGCAGGCCAAGGT-3′) and antisense (5′-CACAGGCGCTTCAGGTGGGG-3′), Chfr sense (5′-ATGGAGCTACACGGGGAAGAGCA-3′) and antisense (5′-TTGGCAGGCTCCAATTCCTCATGGT-3′), and Gapdh sense (5′-CAACTCACTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA-3′) and antisense (5′-TACTTGGCAGGTTTCTCCAGGC-3′). PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels.

Tissue Samples and Immunohistochemistry

To study PARP-1 expression in primary gastric cancers, 19 paraffin-embedded samples from Japanese patients were selected randomly. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before the samples were collected. The samples were stained with an anti PARP-1 antibody (catalog no. 9542, Cell Signaling Technology) using the avidin-biotin complex method as described previously (17). The staining was scored using a three-tiered scoring system (+, weak; ++, moderate; +++, strong).

DNA Methylation Analysis

Genomic DNA from paraffin-embedded gastric cancer samples was purified using the QIAamp DNA FFPE tissue kit (Qiagen) following bisulfite treatment using the EpiTect bisulfite kit (Qiagen). To analyze the percent methylation of CHFR, MetyLight assays were performed using primers and probes as reported previously (18, 19). Alu was used for normalization of data, and genomic DNA from HCT116 cells in which CHFR is 100% methylated was used as a reference. Primers, probes, and the percentage of methylated reference were determined as described previously (20). We used a percentage of methylated reference cutoff of 4 to distinguish methylation-positive (percentage of methylated reference > 4) from methylation-negative (percentage of methylated reference ≤ 4) samples.

Mitotic Index

Cells (5 × 105 or 1 × 106) were cultured for 24 h in 6-well plates and transfected with plasmids or siRNAs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 1 μm docetaxel or 3 mm 3-am inobenzamide (3AB) for an additional 16 h. Thereafter, the cells were harvested with trypsin, and the percentages of mitotic cells were counted as reported previously (21).

Flow Cytometry

One million cells were cultured in 6-mm plates and treated with 1 μm docetaxel or 10 mm 3AB for 48 h and subjected to flow cytometry as reported previously (21). The data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

RESULTS

CHFR Interacts with PARP-1

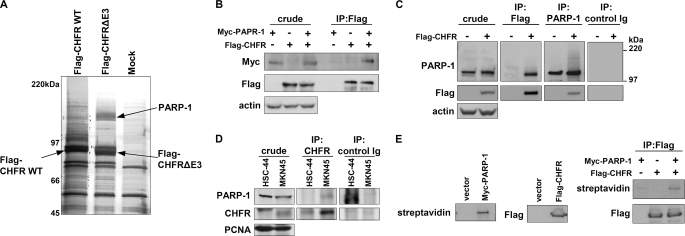

To better understand how CHFR suppresses cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis and how it is functionally regulated in response to mitotic stress, we identified CHFR-interacting proteins using affinity purification by liquid chromatography combined with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). As CHFR has Ub ligase activity, we used a CHFR mutant lacking the 18 amino acids (292 to 309) that form the core amino acid sequence for E3 Ub ligase activity (FLAG-CHFR ΔE3). We then compared the proteins that coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-CHFR to those that coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-CHFR ΔE3. On the basis of these analyses, we identified PARP-1 as a candidate CHFR-interacting protein that bound to CHFR ΔE3 more strongly than to WT CHFR (Fig. 1A). An interaction between FLAG-CHFR and Myc-PARP-1 was validated in HCT116 cells (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, an interaction between endogenous PARP-1 and FLAG-CHFR was confirmed in FLAG-CHFR transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 1C). To confirm an endogenous binding between CHFR and PARP-1, coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed in MKN45 and HSC-44 cells that express or do not express CHFR, respectively (Fig. 1D). The interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 in vitro was also demonstrated (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that CHFR interacts with PARP-1.

FIGURE 1.

CHFR interacts with PARP-1. A, HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-CHFR WT or FLAG-CHFR-deleted E3 activity (ΔE3) expression vectors or mock-transfected, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG resin. Proteins that coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-CHFR were separated by SDS-PAGE and negative gel staining and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. PARP-1 was identified as a CHFR-interacting protein. B, HCT116 cells, which do not express endogenous CHFR, were transfected with FLAG-CHFR and Myc-PARP-1 expression vectors. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-FLAG antibody, and Myc-PARP-1 was coimmunoprecipitated. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against each of the indicated proteins. C, HeLa cells, which do not express endogenous CHFR, were transfected with FLAG-CHFR expression vectors. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG or anti-PARP-1 antibodies or control Ig. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against the indicated proteins. Endogenous PARP-1 and FLAG-CHFR were coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-CHFR and PARP-1, respectively. D, the nuclear extracts form MKN45 and HSC-44cells, which express or do not express endogenous CHFR, respectively, were immunoprecipitated using anti-CHFR antibodies or control Ig. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against the indicated proteins. E, FLAG-CHFR was purified from HEK-293T cells with an anti-FLAG antibody and incubated with the biotinylated PARP-1 generated by in vitro translation. The complexes were thoroughly washed and analyzed by blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody or streptavidin-HRP.

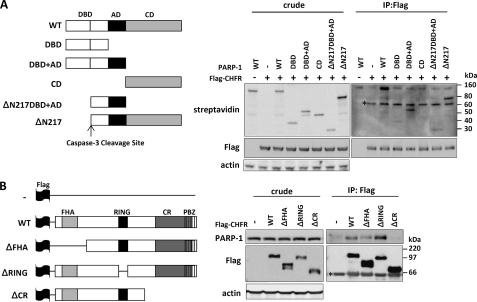

Because PARP-1 contains three conserved domains, a DNA-binding domain (DBD), an automodification domain (AD), and a catalytic domain (CD), we investigated which domain of PARP-1 was essential for its interaction with CHFR. PARP-1 deletion mutants were translated in vitro and incubated with FLAG-CHFR. The PARP-1 CD mutant lacking both the DBD and the AD was not able to bind to FLAG-CHFR at all, whereas the PARP-1 DBD+AD mutant lacking the CD could bind to FLAG-CHFR (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the PARP-1 ΔN217 and ΔN217DBD+AD mutants retaining the AD were coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-CHFR. These data suggest that the AD of PARP-1 is mainly required for its physiological interaction with CHFR.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of the regions required for the interaction between CHFR and PARP-1. A, PARP-1 deletion mutants used in this study (left panel). FLAG-CHFR was purified from HEK-293T cells with an anti-FLAG antibody and incubated with the biotinylated PARP-1 deletion mutants generated by in vitro translation. The crude samples and the complexes were analyzed by blotting with anti-FLAG or anti-actin antibodies or streptavidin-HRP (right panel). ΔN217, Δ N terminus 217 residues; IP, immunoprecipitation. B, CHFR deletion mutants used in this study (left panel). HCT116 cells were transfected with FLAG-CHFR deletion constructs. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody, and endogenous PARP-1 was coimmunoprecipitated (right panel). Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against each of the indicated proteins. ΔFHA, Δ FHA domain; ΔRING, Δ RING finger domain; ΔCR, Δ CR domain; *, nonspecific bands.

We next mapped the domain of CHFR that is required for its interaction with PARP-1. Several FLAG-CHFR deletion mutants were expressed in HCT116 cells, and endogenous PARP-1 was coimmunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody. The CHFR ΔCR mutant was unable to interact with PARP-1, suggesting that CHFR interacts with PARP-1 via its CR region (Fig. 2B). The CHFR ΔRING mutant lacking the RING finger domain, which is responsible for Ub ligase activity, associated with PARP-1 more stably than with CHFR WT, consistent with the results shown in Fig. 1A.

CHFR Polyubiquitinates PARP-1 and Causes Cell Cycle Arrest via PARP-1 Degradation

As shown in Figs. 1A and 2B, the amount of PARP-1 that bound to CHFR mutants lacking Ub ligase activity was greater than the amount that bound to CHFR WT. In addition, immunoprecipitated PARP-1 exhibited a 100–200 kDa smear upon immunoblotting only when FLAG-CHFR was overexpressed in HeLa cells, which do not express endogenous CHFR (Fig. 1C). These data suggested that PARP-1 was polyubiquitinated by CHFR. Then, we performed in vitro ubiquitination assays. The complex of Myc-CHFR with endogenous PARP-1 was coimmunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody and incubated with FLAG-Ub, E1, and E2 (UbcH5c or Ube2N) under standard ubiquitination assay conditions. Because CHFR was found to catalyze both Lys-48-linked and Lys-63-linked polyubiquitination, we examined both UbcH5c, which promotes the synthesis of polyUb chains of various linkages, including Lys-48 and Lys-63, and Ube2N (also known as Ubc13), which catalyzes the synthesis of specific Lys-63 polyUb chains (Fig. 3A). The polyubiquitination of PARP-1 was observed in a FLAG-CHFR-dependent manner in the presence of either UbcH5c or Ube2N (Fig. 3A). The polyubiquitination mediated by Ube2N was lower when compared with that mediated by UbcH5c, indicating that CHFR catalyzed not only Lys-63-linked but also Lys-48-linked and other polyubiquitinations of PARP-1.

FIGURE 3.

CHFR polyubiquitinates PARP-1 and caused cell cycle arrest via PARP-1 degradation. A, HEK-293T cells were mock-transfected or transfected with Myc-CHFR expression vectors, and PARP-1 and Myc-CHFR complexes were coimmunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-Myc antibody (left panel). The resins were thoroughly washed, and in vitro ubiquitination assays were performed (right panel). Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies against each of the indicated proteins. B, HCT116 cells were transfected with FLAG-CHFR or FLAG-CHFR ΔE3 expression vectors. After transfection for 24 h, the cells were treated with or without 10 μm MG132 for 4 h. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PARP-1 antibody, and the precipitates were examined by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin (Ub), anti-PARP-1, or anti-FLAG antibodies. C, HCT116 and HSC44 cells, which do not express endogenous CHFR, were infected with adenoviruses expressing CHFR (CHFR WT), enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), or LacZ. After infection for 64 h, the cells were treated with 0.5 μg/ml of nocodazole (noc) or DMSO (-) for 27 h. The cell lysates were examined by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. D, Chfr+/+ or Chfr−/− MEFs were treated with 1 μm docetaxel for 12 h, and 10 μm MG132 or DMSO was added following 4 h of incubation. Nuclear extractions were collected using the nuclear extract kit (Active Motif, Santa Clara, CA) and subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with antibodies against each of the indicated proteins (top panel). RT-PCR was also performed (bottom panel). E, primary gastric cancer samples were stained using an anti-PARP-1 antibody. CHFR methylation status was analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Magnification ×10. Scale bar = 100 μm. F, statistical analysis of CHFR methylation status and PARP-1 expression levels from 19 primary gastric cancer samples. The Wilcoxon rank test was used to determine whether there was an association between the CHFR methylation status and PARP-1 expression. The p value is indicated. G, DLD-1 Tet-Off cells inducibly expressing FLAG-CHFR (DLD-1 Tet-Off FLAG-CHFR) were cultured with or without 0.1 μg/ml of doxycycline (Dox) for 24 h and transfected with a mixture of three siRNAs targeting PARP-1 (siPARP1) or control oligonucleotides (siCont). After transfection for 4 h, the cells were cultured with or without 0.1 μg/ml of doxycycline for 22 h following treatment with 0.5 μm docetaxel (Doce) for 16 h, and the MI was determined (left panel, bottom). HCT116 cells with stably knocked down PARP-1 (HCT116 siPARP1) or control (HCT116 siCont) cells were mock-transfected or transfected with FLAG-CHFR expression vectors. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 0.5 μm docetaxel for 16 h, and the MI was determined (right panel, bottom). Experiments were performed in triplicate. The mean ± S.D. is indicated by bars and brackets, respectively. p values were calculated using Student's t test. The cell lysates were examined by immunoblotting with each of antibodies against the indicated proteins (top panel).

To examine whether CHFR polyubiquitinated PARP-1 in cells, we transfected CHFR WT and CHFR ΔE3 into HCT116 cells, which do not express endogenous CHFR. Overexpression of CHFR WT promoted polyubiquitination of PARP-1, but overexpression of CHFR ΔE3 did not (Fig. 3B). Treatment with MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, increased the polyUb smear in both CHFR WT and ΔE3-transfected cells, suggesting that PARP-1 could be polyubiquitinated in part by several E3 ligases and degraded by the Ub-proteasome system in response to various stimuli. Indeed, previous work has shown that PARP-1 is subject to ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation in response to DNA damage and heat shock (22, 23). Thus, we sought to determine whether CHFR expression correlated with PARP-1 expression levels during mitotic stress. As shown in Fig. 3C, overexpression of CHFR decreased PARP-1 protein levels in HCT116 and HCS-44 cells, which do not express endogenous CHFR, and mitotic stress induced by nocodazole promoted the degradation of PARP-1, suggesting that CHFR promotes polyubiquitination and degradation of PARP-1 in response to mitotic stress. In agreement with these data, MEFs prepared from Chfr KO mice had higher levels of PARP-1 protein compared with MEFs from Chfr WT mice, even though there was no significant difference in Parp1 mRNA expression between WT and KO MEFs (Fig. 3D). As reported previously, Aurora A and Plk-1, which were polyubiquitination substrates of CHFR, were also overexpressed in Chfr KO MEFs (1). Moreover, in Chfr WT MEFs, PARP-1 protein accumulated with MG132 treatment (Fig. 3D, lanes 1 and 3) and decreased with docetaxel treatment, a microtubule inhibitor (lanes 1 and 5). Interestingly, the decrease in PARP-1 protein expression induced by docetaxel was inhibited by the concomitant use of MG132 (Fig. 3D, lanes 5 and 7). The polyubiquitination of PARP-1 in Chfr WT MEFs was greater than in KO MEFs, supporting that PARP-1 was mainly polyubiquitinated by CHFR. Moreover, MG132 single treatment promoted the polyubiquitination of PARP-1 in both WT and KO MEFs, whereas combination of MG132 and docetaxel significantly increased only in WT MEFs, favoring the idea that PARP-1 was polyubiquitinated by CHFR in responding to mitotic stress, although other E3 ligases could target PARP-1. Although the birth rate and weight of the Chfr KO mice were the same as those of the WT mice, the Chfr KO MEFs exhibited a higher growth rate and had an impaired mitotic checkpoint when compared with the WT MEFs (supplemental Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S1). In addition, in primary human gastric cancers, the PARP-1 protein levels were higher in CHFR-methylated tissues than in CHFR-unmethylated tissues (Fig. 3, E and F), suggesting that silencing of CHFR expression may result in the accumulation of PARP-1 protein.

As mitotic stress facilitated the degradation of PARP-1 in the presence of CHFR, we hypothesized that PARP-1 was involved in the early mitotic checkpoint. To clarify this, we first generated DLD-1 Tet-Off FLAG-CHFR cells in which FLAG-CHFR expression was induced by removing doxycycline. Subsequently, we transfected PARP-1 siRNAs, a mixture of three duplexes, into DLD-1 Tet-Off FLAG-CHFR cells to knock down PARP-1 expression. The increase in the mitotic index (MI, the percentages of the mitotic cells, indicating the abrogation of the prophase checkpoint) induced by docetaxel treatment was attenuated by FLAG-CHFR induction in the control siRNA-transfected DLD-1 cells (Fig. 3G, left panel, compare lanes 5 and 7), indicating that CHFR is involved in cell cycle arrest at prophase. Conversely, in the PARP-1-depleted cells, FLAG-CHFR expression did not affect the progression of cells into mitosis as indicated by the MI (Fig. 3G, left panel, lanes 6 and 8). Remarkably, the MI decreased from 50 to 40% when PARP-1 was knocked down, even in the absence of CHFR expression (Fig. 3G, left panel, lanes 5 and 6), suggesting that the protein level of PARP-1 was critical for progression into mitosis. To validate these results in a different cell line, we generated HCT116 cells that stably expressed PARP-1 siRNA, transfected FLAG-CHFR into these cells, and obtained similar data (Fig. 3G, right panel). The increase in the MI upon docetaxel treatment was attenuated by FLAG-CHFR expression in HCT116 siControl cells (Fig. 3G, right panel, lanes 3 and 4). Conversely, in HCT116 siPARP1 cells with PARP-1 stably knocked down, FLAG-CHFR expression was not significantly involved in cell cycle arrest, as indicated by the MI (Fig. 3G, right panel, lanes 7 and 8). Notably, CHFR-dependent degradation of PARP-1 was observed in these two cell lines. Taken together, these data suggest that in response to mitotic stress, CHFR directly polyubiquitinates PARP-1 and is involved in a delay into mitosis via PARP-1 degradation.

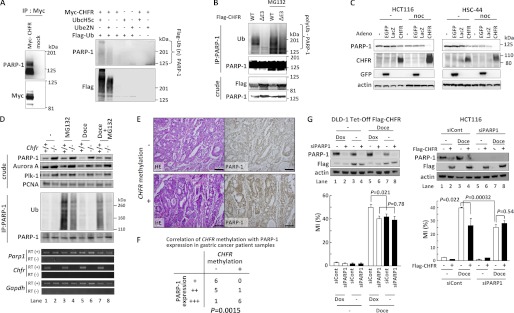

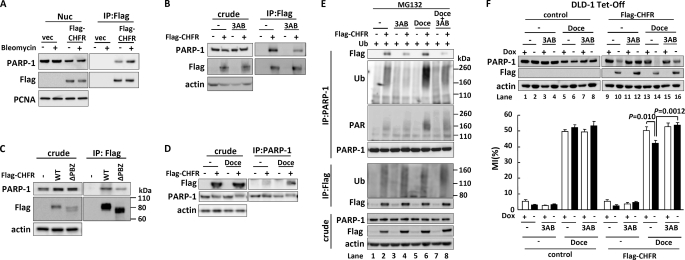

Autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation followed by CHFR-dependent Degradation of PARP-1 Regulates the Mitotic Checkpoint

As PARP-1 has PARylation activity, we assessed its biological implication to the CHFR-dependent checkpoint function. FLAG-CHFR was transfected into HEK-293T cells, and the cells were stimulated with bleomycin, which is widely used to induce PARP-1 activation. Interestingly, the interaction between FLAG-CHFR and PARP-1 was enhanced by bleomycin treatment (Fig. 4A). We assumed that inhibition of PARP-1 PARylation activity would weaken the interaction. To evaluate this assumption, we transfected FLAG-CHFR expression plasmids into HCT116 cells and treated the cells with 3AB, a PARP inhibitor. As shown in the coimmunoprecipitation, the interaction between FLAG-CHFR and PARP-1 was reduced by 3AB treatment (Fig. 4B). Because it has been previously reported that CHFR binds to PAR via its PBZ domain (9), the FLAG-CHFR ΔPBZ mutant was subject to a coimmunoprecipitation assay. As shown in Fig. 4C, FLAG-CHFR ΔPBZ interacted with PARP-1 weaker than FLAG-CHFR WT, indicating that the PARylation of PARP-1 enhances this interaction. It was also observed that FLAG-CHFR ΔPBZ retained the ability to bind to PARP-1 (Fig. 4C), suggesting that CHFR needs its CR region in addition to the PBZ domain to interact with PARP-1 more stably.

FIGURE 4.

PARP-1 poly(ADP-ribosyl)ates CHFR and regulates the mitotic checkpoint. A, HEK-293T cells were mock-transfected or transfected with FLAG-CHFR expression vectors. After transfection for 24 h, the cells were treated for 18 h with 50 μg/ml of bleomycin or DMSO. Nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-FLAG antibody. The precipitates were examined by immunoblotting with each of antibodies against the indicated proteins. B, HCT116 cells were mock-transfected or transfected with a FLAG-CHFR expression vector. After transfection for 24 h, the cells were treated for 16 h with 3 mm 3AB or DMSO. The cell lysates were coimmunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody, and the precipitates were examined by immunoblotting with each of antibodies against the indicated proteins. C, HCT116 cells were mock-transfected or transfected with FLAG-CHFR or FLAG-CHFR ΔPBZ expression vectors. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody. The precipitates were examined by immunoblotting with each of antibodies against the indicated proteins. D, HCT116 cells were mock-transfected or transfected with a FLAG-CHFR expression vector. After transfection for 24 h, the cells were treated for 12 h with 1 μm docetaxel or DMSO (-), and 10 μm MG132 was added following 4 h of incubation. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-PARP-1 following immunoblotting with each of antibodies against the indicated proteins. E, HCT116 cells were mock-transfected or transfected with ubiquitin (Ub) or FLAG-CHFR expression vectors. After transfection for 24 h, the cells were treated for 12 h with 1 mm 3AB, 1 μm docetaxel, or DMSO (-), and 10 μm MG132 was added following 4 h of incubation. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with each of antibodies against the indicated proteins. F, DLD-1 Tet-Off cells expressing inducible FLAG-CHFR (FLAG-CHFR) or mock (control) were cultured for 24 h with or without 0.1 μg/ml of doxycycline (Dox) (left panel) and treated for 16 h with 3 mm 3AB, 1 μm docetaxel (Doce), or DMSO, and the MI was determined. The cell lysates were examined by immunoblotting with antibodies against each of the indicated proteins. Experiments were performed in triplicate. The mean ± S.D. is indicated by bars and brackets, respectively. p values were calculated using Student's t test.

As PARP-1 was polyubiquitinated by CHFR and degraded in response to mitotic stress, we speculated that mitotic stress would induce the PARylation of PARP-1 to promote the binding of PARP-1 to CHFR. PARP-1 could then be polyubiquitinated and degraded by CHFR. To confirm this hypothesis, we first examined whether the interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 was affected in response to mitotic stress. The docetaxel treatment enhanced the interaction between CHFR and PARP-1, indicating mitotic stress promotes the binding of CHFR to PARP-1 (Fig. 4D). To further examine if the PARylation and polyubiquitination status of PARP-1 was altered by mitotic stress in a CHFR-dependent manner, HCT116 cells were cotransfected with FLAG-CHFR and Ub expression plasmids, treated with docetaxel with or without 3AB, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-PARP-1 antibody to quantify the PARylation and polyubiquitination of PARP-1. Exposure to docetaxel increased the autoPARylation and polyubiquitination of PARP-1 in a CHFR-dependent manner (Fig. 4E, lane 6), whereas these modifications were repressed in the presence of 3AB (lane 8). Interestingly, the autoPARylation of PARP-1 was higher in CHFR-expressing cells than in CHFR-non-expressing cells (lanes 5 and 6). As shown in Fig. 3A, CHFR also catalyzed Lys-63-linked and other polyubiquitinations of PARP-1 that could affect the autoPARylation of PARP-1. Autopolyubiquitination of CHFR was slightly affected by docetaxel and 3AB treatment (Fig. 4E, lanes 4, 6, and 8) in agreement with a previous report (9). Collectively, these data demonstrate that in response to mitotic stress, PARP-1 is subject to autoPARylation, which facilitates its interaction with CHFR. PARP-1 is then polyubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome pathway.

We next investigated whether the PARylation activity of PARP-1 affected the CHFR-dependent mitotic checkpoint. DLD-1 Tet-Off FLAG-CHFR cells were exposed to docetaxel with or without 3AB treatment. In accordance with Fig. 3, C, D, and G, docetaxel treatment promoted PARP-1 degradation in a CHFR-dependent manner. Conversely, 3AB treatment partially inhibited the degradation of PARP-1 mediated by CHFR (Fig. 4F, compare lanes 10, 12–14, and 16, respectively). There was little impact of docetaxel or 3AB treatment on PARP-1 protein levels in DLD-1 Tet-Off control cells (lanes 1-8). To quantify the percentages of cells entering mitosis, the MI was determined. Induction of FLAG-CHFR expression diminished the MI increase by docetaxel in the absence of 3AB (Fig. 4F, lanes 13 and 14), but not in the presence of 3AB (lanes 15 and 16). However, 3AB treatment had no effect on the MI in CHFR non-expressing cells (lanes 5–8). These data demonstrate that in CHFR-expressing cells, autoPARylation of PARP-1 triggers its degradation by CHFR, which results in cell cycle arrest, whereas in CHFR-non-expressing cells, autoPARylation does not induce PARP-1 degradation and cells progress into mitosis. When the cells were exposed to a microtubule inhibitor, knocking down PARP-1 contributed to the mitotic checkpoint in a CHFR-independent manner, as shown in Fig. 3G (left panel, lanes 6 and 8; right panel, lanes 7 and 8). Thus, CHFR is involved in the mitotic checkpoint mainly via polyubiquitination of autoPARylated PARP-1.

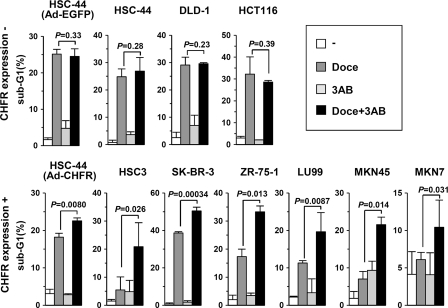

PARP Inhibitors Sensitize Cancer Cells with CHFR-dependent Resistance to Microtubule Inhibitor

Cell cycle checkpoint dysfunction is often associated with sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents (24, 25). Indeed, our previous data have shown that the intact checkpoint function of CHFR is related to resistance to microtubule inhibitors (26), and knocking down CHFR sensitizes cancer cells to these anticancer drugs (21). Hence, our present findings that CHFR preferentially polyubiquitinated autoPARylated PARP-1, which was then degraded via the proteasome pathway (Fig. 4E) and delayed cells in the mitotic checkpoint, led us to test a combination of PARP inhibitors in CHFR-expressing cancer cells that are resistant to microtubule inhibitors. Because BRCA1/2 and PTEN mutations have been found to determine cell sensitivity to PARP inhibitors (16), we chose cancer cells in which mutations in these genes have not been reported. As shown in Fig. 5, the combination of docetaxel and 3AB increased apoptosis in CHFR expressing cells, which were resistant to a single treatment with docetaxel. In CHFR-silenced cells, the concomitant use of 3AB with docetaxel did not increase apoptosis. These results indicate that the combined usage of PARP and microtubule inhibitors for cancers that are resistant to a single chemotherapy may prove to be beneficial.

FIGURE 5.

PARP inhibitors sensitize cancer cells with CHFR-dependent resistance to microtubule inhibitors. One million cells were cultured in 6-mm plates. HCT-44 cells were infected with an adenovirus expressing EGFP (Ad-EGFP) or CHFR (Ad-CHFR) for 12 h at a multiplicity of infection of 50. The cells were treated for 48 h with 1 μm docetaxel (Doce), 10 mm 3AB, or DMSO and subjected to flow cytometry. The percentage of sub-G1 cells is indicated by the bars. Experiments were performed in triplicate. The mean ± S.D. is indicated by bars and brackets, respectively. p values were calculated using Student's t test. The original flow cytometry results are indicated in supplemental Fig. S6.

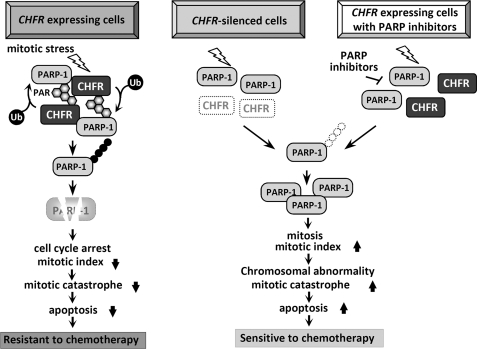

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified PARP-1 as a novel CHFR binding protein and found that the functional relationship between CHFR and PARP-1 regulated CHFR-dependent polyubiquitination and degradation of PARP-1 in response to mitotic stress and then modulated cell cycle arrest at the early mitotic checkpoint. Furthermore, we revealed that the interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 could be regulated by the PARylation activity of PARP-1 (Fig. 6, left). As recent reports have shown that CHFR is an acceptor of PARylation, we also validated PARylation of CHFR by PARP-1 both in vitro and in cells (supplemental Fig. S4). Subsequently, CHFR polyubiquitinated autoPARylated PARP-1, and PARP-1 was then degraded by the proteasome system. Strikingly, the reduction in PARP-1 protein levels resulted in prophase cell cycle arrest (Fig. 3G), implying that there might be a molecular sensor for the detection of PARP-1 levels for cells to enter and proceed into mitosis. Although historically the focus has been on the role of PARP-1 in DNA damage detection and repair, recent studies have suggested a role for PARP-1 in cell cycle regulation. Several studies have reported that G2/M arrest is prolonged in PARP-1-deficient cells and that PARP-1 and PARylation are essential for cells entering mitosis, chromosomal condensation, and progression to cell division, implying that PARP-1 would be one of the key mitotic molecules (27–31). Our data suggested that CHFR functioned in cell cycle arrest by decreasing PARP-1 levels before entering mitosis where sufficient amounts of PARP-1 would be required. Previous reports demonstrated that Aurora A and Plk-1 are polyubiquitination substrates of CHFR and that, by controlling the expression level of these proteins, CHFR modulates the cell cycle regulation (1). Collectively, CHFR plays an important role in the prophase checkpoint by ubiquitinating and degrading several target genes, including PARP-1, Aurora A, and Plk-1. In dead, knocking down of PARP1and AURKA showed arithmetic effect on repressing cells to progress into mitosis induced by mitotic stress (supplemental Fig. 5S), supporting the idea that CHFR might be a master regulator of the prophase checkpoint and a tumor suppressor. In human cancers, increased expression levels of PARP-1 have been reported (32), indicating that abnormal PARP-1 expression could be associated with malignancies (33). Our present data show that a negative correlation between the expression of CHFR and PARP-1 implies that silencing in CHFR could cause overexpression of PARP-1 and result in the checkpoint deregulation and tumorigenesis.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic of the mitotic checkpoint regulated by CHFR and PARP-1 and a cancer therapeutic strategy. In CHFR-expressing cells, mitotic stress induces autoPARylation of PARP-1, which enhances the interaction between CHFR and PARP-1, resulting in an increase in the polyubiquitination/degradation of PARP-1. Decreasing PARP-1 protein levels result in cell cycle arrest at prophase. As shown by our data, cells expressing CHFR exhibit resistance to microtubule inhibitors (left panel). In CHFR-silenced cells, autoPARylation followed by polyubiquitination of PARP-1 is not induced by mitotic stress. PARP-1 protein expression does not decrease, resulting in the progression of cells into mitosis. Dysfunction of the mitotic checkpoint causes mitotic catastrophe. Consequently, CHFR-silenced cells are sensitive to microtubule inhibitors (center panel). In CHFR-expressing cells treated with PARP inhibitors, the autoPARylation of PARP-1 induced by mitotic stress is inhibited by PARP inhibitors. The interaction between CHFR and PARP-1 is diminished, resulting in the repression of CHFR-dependent polyubiquitination/degradation of PARP-1. PARP-1 protein expression does not decrease, resulting in progression into mitosis even in the presence of mitotic stress. Dysfunction of the mitotic checkpoint causes mitotic catastrophe. Therefore, CHFR expressing cells treated with PARP inhibitors are sensitized to microtubule inhibitors (right panel).

As we reported previously, expression of CHFR correlated with resistance to microtubule inhibitors such as docetaxel, and abolishing CHFR caused mitotic catastrophe and sensitized cancer cells to the drugs (see Fig. 6, left and center panels) (21, 26). On the basis of the novel idea that the PARylation activity of PARP-1 regulated CHFR-dependent checkpoint function, in the next set of experiments we demonstrated that PARP inhibitors inhibited autoPARylation of PARP-1 and CHFR-dependent polyubiquitination/degradation of PARP-1 induced by mitotic inhibitors and attenuated the mitotic checkpoint, resulting in enhanced response to docetaxel in CHFR-expressing cells (Fig. 6, right panel). Small molecule inhibitors of PARP have been developed as sensitizers to DNA-damaging chemotherapy or ionizing radiation, and six potent and specific PARP inhibitors are currently undergoing clinical development for various cancers (16, 33). Recently, clinical phase II trials using PARP inhibitors olaparib or iniparib, in combination with a microtubule inhibitor, paclitaxel, have started in gastric cancers and breast cancers. As the results show in Fig. 5, PARP inhibitors sensitized cancer cells with CHFR-dependent resistance to microtubule inhibitors, which sheds new light on a potential strategy for the combined usage of PARP inhibitors with microtubule inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hideyoshi Yokosawa and Masahiro Fujimuro (Hokkaido University, Japan) for the pCI-neo-2S-ubiquitin plasmid. We also thank Drs. Masanori Nojima (Sapporo Medical University) and Yuji Sakuma (Kanagawa Cancer Center, Japan) for helpful suggestions for statistical and pathological analyses, respectively.

This research was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to T. T.) and the Kanzawa Medical Research Foundation (to L. K.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6, Table S1, methods, and references.

- FHA

- forkhead-associated

- CR

- cysteine-rich

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- PBZ

- poly(ADP-ribose)-binding

- PARylation

- poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- ES

- embryonic stem

- DBD

- DNA binding domain

- AD

- automodification domain

- CD

- catalytic domain

- MI

- mitotic index

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yu X., Minter-Dykhouse K., Malureanu L., Zhao W. M., Zhang D., Merkle C. J., Ward I. M., Saya H., Fang G., van Deursen J., Chen J. (2005) CHFR is required for tumor suppression and Aurora A regulation. Nat. Genet. 37, 401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toyota M., Sasaki Y., Satoh A., Ogi K., Kikuchi T., Suzuki H., Mita H., Tanaka N., Itoh F., Issa J. P., Jair K. W., Schuebel K. E., Imai K., Tokino T. (2003) Epigenetic inactivation of CHFR in human tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7818–7823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Privette L. M., Petty E. M. (2008) CHFR. A novel mitotic checkpoint protein and regulator of tumorigenesis. Transl. Oncol. 1, 57–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scolnick D. M., Halazonetis T. D. (2000) CHFR defines a mitotic stress checkpoint that delays entry into metaphase. Nature 406, 430–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kashima L., Toyota M., Mita H., Suzuki H., Idogawa M., Ogi K., Sasaki Y., Tokino T. (2009) CHFR, a potential tumor suppressor, down-regulates interleukin-8 through the inhibition of NF-κB. Oncogene 28, 2643–2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaturvedi P., Sudakin V., Bobiak M. L., Fisher P. W., Mattern M. R., Jablonski S. A., Hurle M. R., Zhu Y., Yen T. J., Zhou B. B. (2002) CHFR regulates a mitotic stress pathway through its RING finger domain with ubiquitin ligase activity. Cancer Res. 62, 1797–1801 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang D., Chen J., Wong J., Fang G. (2002) The checkpoint protein CHFR is a ligase that ubiquitinates Plk1 and inhibits Cdc2 at the G2 to M transition. J. Cell Biol. 156, 249–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bothos J., Summers M. K., Venere M., Scolnick D. M., Halazonetis T. D. (2003) The CHFR mitotic checkpoint protein functions with Ubc13-Mms2 to form Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin chains. Oncogene 22, 7101–7107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahel I., Ahel D., Matsusaka T., Clark A. J., Pines J., Boulton S. J., West S. C. (2008) Poly(ADP-ribose)-binding zinc finger motifs in DNA repair/checkpoint proteins. Nature 451, 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schreiber V., Dantzer F., Ame J. C., de Murcia G. (2006) Poly(ADP-ribose). Novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bièche I., de Murcia G., Lidereau R. (1996) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase gene expression status and genomic instability in human breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2, 1163–1167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Soldatenkov V. A., Albor A., Patel B. K., Dreszer R., Dritschilo A., Notario V. (1999) Regulation of the human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase promoter by the ETS transcription factor. Oncogene 18, 3954–3962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomoda T., Kurashige T., Moriki T., Yamamoto H., Fujimoto S., Taniguchi T. (1991) Enhanced expression of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase gene in malignant lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 37, 223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Idogawa M., Masutani M., Shitashige M., Honda K., Tokino T., Shinomura Y., Imai K., Hirohashi S., Yamada T. (2007) Ku70 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 competitively regulate β-catenin and T-cell factor 4-mediated gene transactivation. Possible linkage of DNA damage recognition and Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 67, 911–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimizu S., Nomura F., Tomonaga T., Sunaga M., Noda M., Ebara M., Saisho H. (2004) Expression of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in human hepatocellular carcinoma and analysis of biopsy specimens obtained under sonographic guidance. Oncol. Rep. 12, 821–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rouleau M., Patel A., Hendzel M. J., Kaufmann S. H., Poirier G. G. (2010) PARP inhibitor: PARP1 and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 293–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Idogawa M., Yamada T., Honda K., Sato S., Imai K., Hirohashi S. (2005) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a component of the oncogenic T-cell factor-4/β-catenin complex. Gastroenterology 128, 1919–1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kawasaki T., Ohnishi M., Nosho K., Suemoto Y., Kirkner G. J., Meyerhardt J. A., Fuchs C. S., Ogino S. (2008) CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) colorectal cancer shows not only few methylated CIMP-high-specific CpG islands, but also low-level methylation at individual loci. Mod. Pathol. 21, 245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Igarashi S., Suzuki H., Niinuma T., Shimizu H., Nojima M., Iwaki H., Nobuoka T., Nishida T., Miyazaki Y., Takamaru H., Yamamoto E., Yamamoto H., Tokino T., Hasegawa T., Hirata K., Imai K., Toyota M., Shinomura Y. (2010) A novel correlation between LINE-1 hypomethylation and the malignancy of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 5114–5123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weisenberger D. J., Siegmund K. D., Campan M., Young J., Long T. I., Faasse M. A., Kang G. H., Widschwendter M., Weener D., Buchanan D., Koh H., Simms L., Barker M., Leggett B., Levine J., Kim M., French A. J., Thibodeau S. N., Jass J., Haile R., Laird P. W. (2006) CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 38, 787–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ogi K., Toyota M., Mita H., Satoh A., Kashima L., Sasaki Y., Suzuki H., Akino K., Nishikawa N., Noguchi M., Shinomura Y., Imai K., Hiratsuka H., Tokino T. (2005) Small interfering RNA-induced CHFR silencing sensitizes oral squamous cell cancer cells to microtubule inhibitors. Cancer Biol. Ther. 4, 773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin N., Schwamborn K., Schreiber V., Werner A., Guillier C., Zhang X. D., Bischof O., Seeler J. S., Dejean A. (2009) PARP-1 transcriptional activity is regulated by sumoylation upon heat shock. EMBO J. 28, 3534–3548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang T., Simbulan-Rosenthal C. M., Smulson M. E., Chock P. B., Yang D. C. (2008) Polyubiquitylation of PARP-1 through ubiquitin K48 is modulated by activated DNA, NAD+, and dipeptides. J. Cell. Biochem. 104, 318–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bunz F., Hwang P. M., Torrance C., Waldman T., Zhang Y., Dillehay L., Williams J., Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1999) Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki H., Itoh F., Toyota M., Kikuchi T., Kakiuchi H., Imai K. (2000) Inactivation of the 14–3-3 sigma gene is associated with 5′ CpG island hypermethylation in human cancers. Cancer Res. 60, 4353–4357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Satoh A., Toyota M., Itoh F., Sasaki Y., Suzuki H., Ogi K., Kikuchi T., Mita H., Yamashita T., Kojima T., Kusano M., Fujita M., Hosokawa M., Endo T., Tokino T., Imai K. (2003) Epigenetic inactivation of CHFR and sensitivity to microtubule inhibitors in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 63, 8606–8613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tentori L., Muzi A., Dorio A. S., Scarsella M., Leonetti C., Shah G. M., Xu W., Camaioni E., Gold B., Pellicciari R., Dantzer F., Zhang J., Graziani G. (2010) Pharmacological inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activity in PARP-1 silenced tumour cells increases chemosensitivity to temozolomide and to a N3-adenine selective methylating agent. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 10, 368–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wesierska-Gadek J., Schloffer D., Gueorguieva M., Uhl M., Skladanowski A. (2004) Increased susceptibility of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 knockout cells to antitumor triazoloacridone C-1305 is associated with permanent G2 cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 64, 4487–4497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tanuma S., Kanai Y. (1982) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of chromosomal proteins in the HeLa S3 cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 6565–6570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saxena A., Saffery R., Wong L. H., Kalitsis P., Choo K. H. (2002) Centromere proteins Cenpa, Cenpb, and Bub3 interact with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 protein and are poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26921–26926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang P., Jacobson M. K., Mitchison T. J. (2004) Poly(ADP-ribose) is required for spindle assembly and structure. Nature 432, 645–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miwa M., Masutani M. (2007) PolyADP-ribosylation and cancer. Cancer Sci. 98, 1528–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Annunziata C. M., O'Shaughnessy J. (2010) Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase as a novel therapeutic target in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 4517–4526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.