Background: Leishmania synthesize pyrimidine nucleotides via biosynthetic and salvage pathways.

Results: Genetic blocks in pyrimidine biosynthesis and/or salvage can impact both life cycle stages of Leishmania.

Conclusion: Pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage both contribute to Leishmania homeostasis in animal infections.

Significance: Functional characterization of pyrimidine pathways is crucial for understanding pyrimidine metabolism and validation of potential drug targets and vaccine strains.

Keywords: Gene Knockout, Genetics, Infection, Infectious Diseases, Leishmania donovani, Metabolism, Pyrimidine, Pyrimidine Biosynthesis, Pyrimidine Salvage

Abstract

Protozoan parasites of the Leishmania genus express the metabolic machinery to synthesize pyrimidine nucleotides via both de novo and salvage pathways. To evaluate the relative contributions of pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage to pyrimidine homeostasis in both life cycle stages of Leishmania donovani, individual mutant lines deficient in either carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (CPS), the first enzyme in pyrimidine biosynthesis, uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRT), a salvage enzyme, or both CPS and UPRT were constructed. The Δcps lesion conferred pyrimidine auxotrophy and a growth requirement for medium supplementation with one of a plethora of pyrimidine nucleosides or nucleobases, although only dihydroorotate or orotate could circumvent the pyrimidine auxotrophy of the Δcps/Δuprt double knockout. The Δuprt null mutant was prototrophic for pyrimidines but could not salvage uracil or any pyrimidine nucleoside. The capability of the Δcps parasites to infect mice was somewhat diminished but still robust, indicating active pyrimidine salvage by the amastigote form of the parasite, but the Δcps/Δuprt mutant was completely attenuated with no persistent parasites detected after a 4-week infection. Complementation of the Δcps/Δuprt clone with either CPS or UPRT restored infectivity. These data establish that an intact pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway is essential for the growth of the promastigote form of L. donovani in culture, that all uracil and pyrimidine nucleoside salvage in the parasite is mediated by UPRT, and that both the biosynthetic and salvage pathways contribute to a robust infection of the mammalian host by the amastigote. These findings impact potential therapeutic design and vaccine strategies for visceral leishmaniasis.

Introduction

Leishmania donovani is a member of the Trypanosomatidae family of protozoan parasites and the etiologic agent of visceral leishmaniasis, a devastating and invariably fatal disease if untreated. The parasite sustains a digenetic life cycle existing as the motile, extracellular promastigote in the phlebotomine sandfly vector and as the immotile, intracellular amastigote within the phagolysosome of macrophages and other reticuloendothelial cells of the mammalian host. There is no vaccine for leishmaniasis, and the current aggregate of chemotherapeutic agents employed to treat the disease is far from ideal and is compromised by toxicity, invasive routes of administration, and resistance. Thus, the need to find new drugs and identify new drug targets for preventing or treating leishmaniasis (or for that matter any parasitic disease) is acute.

The purine pathway in protozoan parasites has garnered extensive attention because, unlike their vertebrate hosts, all protozoan parasites that have been studied to date lack the capacity to synthesize the purine ring de novo (1). Thus, all of these human pathogens must obligatorily scavenge purines from their hosts in order to survive and proliferate. In contrast, most, but not all, protozoan parasites can synthesize pyrimidine nucleotides (1). Leishmania are pyrimidine prototrophs but also express a variety of salvage and interconversion enzymes that enable them to acquire preformed pyrimidine nucleobases or nucleosides from either the culture medium or the host environment. Studies on the pyrimidine pathway in Leishmania, however, have been very limited. All six enzymes of the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway have been detected in Leishmania mexicana (2), and the carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (CPS)2 gene sequence from L. mexicana has been reported (3). In addition, Leishmania express uracil and uridine transport activities (1, 4, 5) as well as uracil phosphoribosyltransferase (UPRT) (6), uridine hydrolase (7), cytidine deaminase (1, 8), and thymidylate synthase (9, 10) activities. The uridine transporter of L. donovani (11, 12), the uridine hydrolase from both L. donovani (13) and Leishmania major (7), and the bifunctional dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase proteins from several Leishmania species (9, 10, 14) have been identified at the molecular level and characterized. Biochemical and genetic investigations on the pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes as well as the enzymes that salvage preformed pyrimidines from the host are virtually nonexistent at the molecular level for this genus. A schematic representation of the pyrimidine transport, biosynthesis, salvage, and interconversion pathways is depicted in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of pyrimidine metabolism in L. donovani. The double curved line represents the parasite plasma membrane, whereas arrows indicate the biochemical function or transport activity of the following: CPS (1), ACT (2), DHO (3), DHODH (4), UMPS (5 and 6), nucleoside transporter 1 (7), uracil transporter (8), cytidine deaminase (9); uridine phosphorylase (10), nucleoside hydrolase (11), and UPRT (12).

Aoki and co-workers (15) first noted that the genes encoding all six pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes of Trypanosoma cruzi, another protozoan parasite and member of the Trypanosomatidae family, are syntenic in the genome of the parasite. Bioinformatic analysis of the annotated genomes of four Leishmania species as well as the genome of Trypanosoma brucei reveal a similar clustering of pyrimidine biosynthesis genes in all of these human pathogens (16–19). Limited in vitro studies on the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway enzymes in cultured trypanosomatids have been performed. These include one report that implies that disruption of the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) genes that encode the fourth enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway in T. cruzi is a lethal event (20) and a similar analysis in T. brucei in which RNAi knockdown of DHODH restrained parasite growth in pyrimidine-deficient growth medium (21). In addition, a recent article showed a modest (∼3-fold) growth inhibition of intracellular amastigotes upon genetic ablation of the CPS gene in T. cruzi (22). However, in vivo evaluation of the relative contributions of trypanosomatid pyrimidine salvage and de novo synthesis pathways to parasite survival are lacking.

To initiate a dissection of the pyrimidine pathway in L. donovani, a species in which many functional studies on the purine pathway have been performed (23–28), the entire complement of L. donovani pyrimidine biosynthesis genes as well as the UPRT gene have been cloned, and their coding regions have been sequenced. Additionally, independent mutant L. donovani strains deficient either in the first enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway, CPS, in UPRT, or in both CPS and UPRT have been constructed using targeted gene replacement strategies. Cultured promastigotes of the Δcps and Δcps/Δuprt lines exhibited a conditionally lethal growth phenotype because viability and sustained proliferation required the provision of an exogenous source of pyrimidine in the culture medium. The Δcps null mutant remained capable of establishing an infection in susceptible BALB/c mice, indicating that the intracellular L. donovani amastigote within the mammalian macrophage phagolysosome has access to a salvageable pyrimidine pool. The Δuprt knockout was prototrophic for pyrimidines but was incapable of incorporating either uracil or uridine into its nucleotide pools, establishing UPRT as the focal enzyme within the pyrimidine salvage pathway in L. donovani. The Δcps/Δuprt double knockout, however, was fully attenuated with no persistent parasites observed 4 weeks postinoculation. These findings intimate that an effective therapeutic strategy targeting the pyrimidine pathway will require simultaneous inhibition of both pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage and reinforce the potential for using the Δcps/Δuprt line as a live attenuated vaccine for visceral leishmaniasis prevention.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials, Chemicals, and Reagents

[5,6-3H]Uracil (38 Ci/mmol) and [5,6-3H]uridine (43.6 Ci/mmol) were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA), and [32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol) was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA). Unlabeled pyrimidine bases and nucleosides were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and Fisher. All restriction and DNA-modifying enzymes were acquired from either Invitrogen or New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) or Invitrogen. PfuTurbo high fidelity DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies Co., Santa Clara, CA) was employed for all PCR amplifications of DNA sequences. The transfection vectors pX63-HYG (29), pX63-PHLEO (30), and pXG-NEO (31) were generously furnished by Dr. Stephen M. Beverley (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). Hygromycin was procured from Roche Applied Science, and phleomycin was from Research Products International (Mt. Prospect, IL), blasticidin was from Fisher, G418 was from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, MD), and puromycin and FBS were from Sigma-Aldrich. All other chemicals and reagents were of the highest quality commercially available.

Parasite Cell Culture

The wild type LdBob L. donovani clone (32) was obtained from Dr. Stephen M. Beverley. LdBob is derived from the 1S2D strain (33, 34), which had been acclimated for growth as axenic amastigotes (32, 35). Promastigotes were cultured at 26 °C in pH 7.4 DME-L medium that was supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 μm hypoxanthine (36). Parasite lines that were auxotrophic for pyrimidines were routinely maintained in medium supplemented with 250 μm uridine or, when necessary to bypass a concomitant deficiency in pyrimidine salvage, 2 mm orotate. For the investigation of parasite growth in exogenous pyrimidine sources and for the incorporation of [5,6-3H]uracil and [5,6-3H]uridine, the medium was supplemented with 10% Serum Plus (SAFC Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) instead of FBS. Serum Plus lacks the residual pyrimidines found in FBS that would interfere with the assay. The single-cell cloning protocols for L. donovani promastigotes employed in this investigation were originally described by Iovannisci and Ullman (37).

Parasite Growth

The abilities of wild type, Δcps, and Δcps/Δuprt parasites to proliferate in various pyrimidine sources were determined by placing 5.0 × 103 parasites into individual wells of a 96-well cell culture plate containing 0.2 ml of growth medium supplemented with either a 100 μm, 500 μm, or 2 mm concentration of the appropriate pyrimidine. Wells lacking pyrimidine supplement were included as controls. Uracil growth inhibition experiments were conducted using the same protocol but as a function of multiple uracil concentrations. At the end of each growth experiment, parasites were enumerated using the vital dye alamarBlueTM (BIOSOURCE) technology (38). Reduction of alamarBlueTM was monitored at 570 and 600 nm on a Multiskan Ascent plate reader (Thermo Labsystems, Vaantaa, Finland). The percentage of dye reduction was calculated according to the formula outlined in the manufacturer's brochure. The greatest reduction was expressed as maximal proliferation.

To determine parasite growth rates, promastigotes were initially seeded at a concentration of 1 × 106 parasites/ml in 10 ml of permissive medium (DME-L medium containing 10% FBS, 100 μm hypoxanthine, and either 250 μm cytidine for Δcps mutants or 2 mm orotate for Δcps/Δuprt mutants). Cultures were incubated overnight to attain logarithmic growth and were used to inoculate new cultures at 1 × 106 parasites/ml in 10 ml of similar permissive medium. The parasite densities were enumerated by a hemacytometer every 8–16 h over a 48-h period. The effect of uracil concentration on the growth rate of Δcps promastigotes was ascertained using the identical protocol except that once logarithmic growth was achieved, parasites were seeded at a density 1 × 106 in 5 ml of DME-L medium that was supplemented with either 100 μm, 500 μm, 2 mm, or 4 mm uracil. Parasite densities were determined by hemacytometer in 8–24-h intervals over 10 days.

Molecular Cloning of CPS and UPRT

Because of the synteny of pyrimidine biosynthesis genes in trypanosomatids (15–19), the entire pyrimidine biosynthesis gene cluster from L. donovani was isolated using DNA probes corresponding to coding regions from both the CPS and DHODH genes from L. major, which correspond to the 5′- and 3′-ends of the syntenic region (16). The CPS (LmjF16.0590) and DHODH (LmjF16.0530) sequences were amplified from L. major genomic DNA via PCR using the primers depicted in supplemental Table S1 and cloned into the pCR® 2.1-TOPO® vector of the TOPO TA CloningTM kit (Invitrogen). The LmCPS probe fragment was then used to screen an L. donovani cosmid library using high stringency conditions. Twenty positive cosmid clones were pooled and plated for a secondary screen with the LmDHODH probe to allow isolation of cosmids containing the full pyrimidine biosynthesis locus. Cosmid DNA was purified by conventional methods from a cosmid that hybridized to both probes. The genes encoding CPS (JN882600), DHODH (JQ436846), aspartate carbamoyltransferase (ACT) (JQ436847), dihydroorotase (DHO) (JQ436845), and the bifunctional UMP synthase (UMPS) protein (JN882599) that catalyzes the last two steps in de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis were then sequenced bidirectionally using automated sequencing available at the Oregon Health and Science University, and the sequences deposited in GenBankTM (accession numbers shown in parentheses).

The CPS ORF was amplified from cosmid DNA by PCR using the primers depicted in supplemental Table S1 and directionally cloned into the pET200/D-TOPO® Escherichia coli expression vector (Invitrogen), which automatically tags encoded proteins with an amino-terminal His6 tag. Similarly, the UPRT ORF was cloned into the pET200/d-TOPO® expression vector following PCR amplification using primers (see supplemental Table S1) designed to the UPRT sequence provided in the annotated genome sequence of Leishmania infantum (16), a species closely related to L. donovani. The cloned UPRT gene from vectors derived from three independent PCRs was sequenced using vector-specific primers, and the sequence was deposited in GenBank (JN882601).

Creation of Constructs for CPS Gene Replacement

The 5′- and 3′-sequences flanking the CPS ORF were identified and sequenced from the cosmid DNA. To construct gene targeting cassettes to replace both CPS alleles, ∼600 bp of 5′- and 3′-flanking regions were amplified by PCR and subcloned sequentially into the HindIII/SalI or BamHI sites, respectively, of the pX63-HYG (29) and pX63-PHLEO (30) plasmids. An additional HindIII site was included in the reverse primer for the 3′-targeting sequence to facilitate excision of the targeting cassette (supplemental Tables S1 and S2).

Creation of Constructs for UPRT Gene Replacement

Targeting constructs for the replacement of UPRT via homologous recombination were generated according to the multifragment ligation method of Fulwiler et al. (39). The 5′- and 3′-UPRT targeting sequence primers (supplemental Table S1) encoded SfiI restriction sites that provided unique overhangs upon SfiI digestion, facilitating simultaneous and ordered targeting vector assembly. UPRT targeting vectors that encoded expression cassettes conferring resistance to hygromycin or G418 were designated pTRG-HYG-Δuprt and pTRG-NEO-Δuprt, respectively (39). An additional targeting construct, pTRG-bsd-Δuprt, encoded a blasticidin S deaminase gene (bsd), which relied upon the UPRT gene flanking sequences to provide the appropriate pre-mRNA processing signals for expression of blasticidin resistance.

Construction of CPS and UPRT Complementation Vectors

The CPS and UPRT ORFs with vector-encoded His6 tags were excised from pET200-CPS or pET200-UPRT expression vectors (described above) with NdeI and BspEI and inserted into the corresponding sites of pXG-NEO-HA, a derivative of pXG-NEO into which a human influenza HA epitope tag and additional restriction sites had been incorporated to allow the generation of NH2-terminal HA tag protein fusions.3 The CPS and UPRT sequences in these vectors, designated pXG-NEO-CPS and pXG-NEO-UPRT, respectively, encoded both HA and His6 tags at the NH2 terminus.

To generate complementation vectors with drug resistance markers compatible with the Δcps/Δuprt null strain, the CPS and UPRT ORFs were excised from pXG-NEO-CPS or pXG-NEO-UPRT vectors with AvrII and XbaI and inserted into pRP-M-PAC, yielding pRP-M-PAC-CPS and pRP-M-PAC-UPRT, which confer puromycin resistance. The pRP-M vector expresses transgenes from the ribosomal RNA (RRNA) promoter upon integration into the RRNA array and has been used for complementation of Δumps parasites (40).

Creation of Transgenic L. donovani

A summary of the gene targeting strategy is provided in supplemental Table S2. For generation of the Δcps null strains from wild type L. donovani, the pX63-PHLEO-Δcps and pX63-HYG-Δcps vectors were digested with HindIII, and the targeting cassettes were gel-purified and then transfected using a GenePulser XCell (Bio-Rad) apparatus and the electroporation parameters originally reported previously (41). Following transfection of wild type LdBob promastigotes with the PHLEO targeting cassette, heterozygous CPS/cps clones were selected on semisolid medium containing 50 μg/ml phleomycin. Confirmed CPS/cps heterozygote clones were subsequently transfected with the HYG targeting cassette and selected on semisolid medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml hygromycin and 50 μg/ml phleomycin to select for homozygous Δcps knockouts and 500 μm each uracil, uridine, and orotate to allow for growth via salvage of exogenous pyrimidines (supplemental Table S2).

The Δuprt and Δcps/Δuprt null strains were created in both wild type and Δcps L. donovani following methods similar to those delineated above. All pTRG-Δuprt vectors were digested with PacI to liberate the targeting cassettes containing the UPRT flanking regions. The targeting fragments were gel-purified and transfected into either wild type or Δcps parasites as indicated in supplemental Table S2. Clonal Δuprt or Δcps/Δuprt knockouts were then created in UPRT/uprt heterozygotes by a second round of transfection with the appropriate Δuprt targeting cassette and selection on medium containing 25 μg/ml blasticidin and either 50 μg/ml hygromycin (Δuprt) or 20 μg/ml G418 (Δcps/Δuprt). Orotate (2 mm) was used as the pyrimidine source in the selections for both the Δcps/UPRT/uprt and Δcps/Δuprt transgenic lines to enable pyrimidine salvage by a UPRT-independent route (i.e. through orotate phosphoribosyltransferase, part of the UMPS bifunctional protein).

The genetic deficiencies of the Δcps and Δcps/Δuprt knockouts were complemented via episomal or integrating constructs, respectively, expressing either CPS or UPRT (supplemental Table S2). The Δcps line was transfected with pXG-NEO-CPS and selected in medium containing 20 μg/ml G418. Because Δcps/Δuprt clones contained drug resistance markers for hygromycin, phleomycin, blasticidin, and G418, integrating CPS (pRP-M-PAC-CPS) and UPRT (pRP-M-PAC-UPRT) vectors conferring puromycin resistance, were used for complementation. The vectors were linearized via AvrII digestion prior to transfection into Δcps/Δuprt null strains and selection in DME-L medium containing 50 μm puromycin. The CPS “add-back” cell lines were designated Δcps[pCPS] and Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS], and UPRT add-back clones were designated Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT].

Uracil Incorporation Assays

The rates by which wild type or Δuprt promastigotes incorporated [5,6-3H]uracil or [5,6-3H]uridine into their pyrimidine nucleotide pools were determined via a DE81 filter binding assay adapted from Ref. 27. Cultures of exponentially growing wild type and Δuprt promastigotes were diluted to a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml into medium supplemented with Serum Plus and incubated at 26 °C for 24 h. Parasites were pelleted by centrifugation, rinsed twice with PBS, and resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 107 cells/ml in medium lacking pyrimidines. 1.0 ml of cell suspension was aliquoted into wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate, and the incorporation reaction was initiated by the addition of 26.3 pmol of [5,6-3H]uracil (38 Ci/mmol) or 22.9 pmol of [5,6-3H]uridine (43.6 Ci/mmol) to each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature for the duration of the experiment. At various time points, 100 μl of cell suspension was pipetted onto individual DE81 filter discs, and the discs were placed on two layers of Whatman 3MM chromatography paper (Whatman International, Ltd., Maidstone, UK) presoaked with lysis buffer consisting of 1% Triton X-100 and 2 mm uracil to quench the reaction. The filters were washed three times in 1,500 ml of distilled H2O for 3 min each to remove unincorporated [5,6-3H]uracil or [5,6-3H]uridine, rinsed once in 95% ethanol, and dried at 60 °C for 5 min. The dried filters were placed in scintillation vials with 3 ml of EcoLume scintillent (MP Biomedicals), and the extent of 3H incorporation was assessed with a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter.

Mouse Infections

Groups of three or five 6–7-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were each inoculated via tail vein injection with 5 × 106 of either wild type, Δcps, Δuprt, Δcps/Δuprt, Δcps[pCPS], Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS], or Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT] stationary phase promastigotes (23, 42). Prior to injection, each L. donovani strain except Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS] and Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT] was passaged through mice (35) to revitalize ancillary virulence determinants that might have attenuated as a result of prolonged in vitro culture. One or 4 weeks postinfection, mice were sacrificed, and their livers and spleens were harvested (42). Single-cell suspensions from the mouse organs were prepared by sieving through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and parasite loads were determined in 96-well microtiter plates using the limiting dilution assay of Buffet et al. (43). The DME-L growth medium in which the organ-derived wild type, Δcps, Δuprt, Δcps/Δuprt, Δcps[pCPS], Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS], and Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT] parasites were titered was supplemented with a permissive pyrimidine source as needed as well as with 100 μm hypoxanthine and 10% FBS.

Macrophage Infections

Mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested as described (42). Bulk cultures of wild type and Δcps/Δuprt promastigotes were allowed to grow to early stationary phase, washed two times in PBS, and resuspended in DME-L medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Mouse peritoneal macrophages were seeded into 4-well Lab-TekII chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International Corp., Naperville, IL) at a density of 2 × 105 cells in 1.0 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 4 mm l-glutamine, 1.5 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate, and 4.5 mg/ml glucose and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 16 h. Adherent macrophages were incubated with 2.0 × 106 stationary phase promastigotes of each strain for 6 h, after which the chambers were rinsed 10 times in PBS to remove residual extracellular promastigotes. The macrophages and parasites were immediately fixed and stained with the Diff-Quik kit (International Medical Equipment Inc., San Marcos, CA), and images were captured with a Zeiss AxioCam MRm camera coupled to a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M scope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY) using a ×60 oil immersion objective to allow visual enumeration of parasite-infected macrophages.

RESULTS

Isolation of L. donovani Pyrimidine Gene Cluster

The L. donovani CPS was isolated from a cosmid library as part of a strategy to isolate the entire complement of pyrimidine biosynthesis genes. Given that the genes encoding the biosynthetic pathway are known to be colocalized on the genomes of T. cruzi, T. brucei, L. major, L. mexicana, and L. infantum trypanosomatids (15–19), sequences within the 5′- and 3′-ORFs of the L. major cluster, CPS and DHODH, respectively, were amplified by PCR from L. major genomic DNA, and each was used to probe replica filters containing DNAs from an L. donovani cosmid library. Several cosmids that accommodated the entire ensemble of pyrimidine biosynthesis genes were obtained, and the ORFs of CPS, ACT, DHO, DHODH, and UMPS were sequenced. The L. donovani CPS is a polypeptide of 1,842 amino acids and, like the other trypanosomatid CPSs, is a bifunctional polypeptide that encodes an NH2-terminal glutamine amidotransferase domain that removes the amido nitrogen from glutamine to enable carbamoylphosphate synthesis from CO2. Unlike the mammalian enzyme (44, 45), the trypanosomatid CPS proteins, including the L. donovani CPS, are not part of a trifunctional polypeptide encoding ACT and DHO. A multisequence alignment of the L. donovani, T. cruzi, human, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae CPS proteins is shown in supplemental Fig. S1A. The properties of the other L. donovani pyrimidine biosynthetic enzymes have been described (40) or will be described elsewhere.

Isolation of UPRT

The L. donovani UPRT gene was isolated from L. donovani genomic DNA via PCR using primers corresponding to the annotated UPRT genomic sequence from the closely related species L. infantum (16). DNA sequencing revealed that L. donovani UPRT shares 100% identity at the nucleotide level to L. infantum UPRT. The L. donovani UPRT protein has been expressed in E. coli and purified to near homogeneity, and its activity as a uracil phosphoribosyltransferase has been confirmed.4 A multisequence alignment of the UPRTs from L. donovani, Toxoplasma gondii, and S. cerevisiae is provided in supplemental Fig. S1B.

Creation of Δcps, Δuprt, and Δcps/Δuprt Null Strains

Δcps, Δuprt, and Δcps/Δuprt mutants were created within LdBob, a strain of L. donovani capable of transformation into axenic amastigotes (32), which retains its capacity to infect mammalian macrophages and to sustain a prolonged infection in susceptible mice (23, 42). The CPS ORF was replaced by PHLEO or HYG drug resistance cassettes via double targeted gene replacement. The resulting Δcps null strains were selected on plates containing 500 μm uracil, 500 μm uridine, and 500 μm orotate to circumvent potential pyrimidine auxotrophy. The correct allelic replacements at the CPS locus in the Δcps null mutants were confirmed by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA probed with both the CPS ORF and its 5′-flank (Fig. 2, A and B).

FIGURE 2.

Southern blot analysis of Δcps, Δuprt, and Δcps/Δuprt knockouts. Genomic DNA from wild type (lane 1), Δcps (lane 2), Δuprt (lane 3), and Δcps/Δuprt (lane 4) parasites was digested with either SacI (A and C) or XhoI (B and D), fractionated on a 1% agarose gel, and blotted onto nylon membranes. Blots were hybridized under high stringency conditions with probes for the CPS ORF (A), CPS 5′-flank (B), UPRT ORF (C), or UPRT 3′-flank (D). The arrows denote band positions corresponding to wild type CPS (A and B) and UPRT (C and D) alleles or to alleles in which the wild type genes have been replaced by HYG (B and D, lane 3), PHLEO (B), bsd (D), or NEO (D, lane 4) drug resistance markers.

The Δuprt and Δcps/Δuprt null mutants were generated by replacing the UPRT gene from wild type and Δcps parasites, respectively, with compatible drug resistance markers. Although selection of Δuprt null mutants required no pyrimidine supplementation of the growth medium, selection of the Δcps/Δuprt null mutants, which have lost the capacity for both de novo synthesis and normal salvage of pyrimidines, was absolutely dependent upon supplementation with 2 mm orotate. Orotate, an intermediate of de novo synthesis, is converted to UMP via UMPS and is thus capable of circumventing both the Δcps and Δuprt lesions. Southern blot analysis using the UPRT ORF and 3′-flank as hybridization probes confirmed deletion of the UPRT locus in both the Δuprt and Δcps/Δuprt knockouts (Fig. 2, C and D).

Pyrimidine Requirements of Mutant Parasites

After confirmation of the Δcps and Δuprt genotypes, the Δcps, Δuprt, and Δcps/Δuprt mutants were tested for their abilities to grow in medium in the absence or presence of pyrimidine supplement. Although wild type L. donovani grew robustly in the absence of pyrimidines, both the Δcps single and Δcps/Δuprt double knockouts were auxotrophic for pyrimidines and growth-arrested after 24 h in the absence of pyrimidine (Fig. 3, A–C). That the pyrimidine auxotrophy of the Δcps and Δcps/Δuprt strains was caused by the Δcps lesion was confirmed by the pyrimidine prototrophy of the Δcps[pCPS] and Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS] add-back lines (see “Experimental Procedures”). The Δuprt promastigotes, as expected, were also prototrophic for pyrimidines (see Fig. 4). The pyrimidine requirement conferred by the Δcps lesion was further evaluated as a function of the pyrimidine source and concentration (100 μm, 500 μm, and 2 mm). The Δcps single knockout exhibited robust growth at all three concentrations of uridine and deoxyuridine, at 500 μm and 2 mm cytidine and deoxycytidine, at 2 mm orotate and dihydroorotate, and at 100 μm uracil (Fig. 3B). Maximum growth was not achieved at lower concentrations of cytidine, deoxycytidine, orotate, or dihydroorotate, and interestingly, 500 μm and 2 mm uracil proved inhibitory to Δcps proliferation. Cytosine, thymine, and thymidine were incapable of rescuing the Δcps knockouts at all concentrations tested (Fig. 3B). Conversely, only 2 mm orotate and dihydroorotate were permissive for Δcps/Δuprt growth, whereas uracil, cytosine, thymine, and their corresponding nucleosides were nonpermissive at all concentrations (Fig. 3C). Complementation of the Δuprt lesion by UPRT in the Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT] mutant rescued the pyrimidine salvage defect enabling growth in all pyrimidine nucleobases and nucleosides that rescued the Δcps parasites (data not shown). Under conditions permissive for maximum growth, the growth rates of wild type, Δcps, Δuprt, and Δcps/Δuprt promastigotes were equivalent with doubling times of ∼16 h (Fig. 4). Lack of growth under all experimental conditions, except supplementation of Δcps growth medium with high uracil, could not be ascribed to toxicity triggered by the extracellular pyrimidine because the growth of wild type L. donovani under all growth conditions was unaffected by the addition of any source or concentration of pyrimidine to the medium (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Growth of wild type, Δcps, and Δcps/Δuprt promastigotes in various pyrimidine supplements. Wild type (A), Δcps (B), and Δcps/Δuprt (C) promastigotes were tested for their ability to grow in medium with or without supplementation by the indicated pyrimidines at concentrations of 100 μm (black bars), 500 μm (white bars), or 2 mm (hashed bars). The percentage of maximum growth of wild type and mutant promastigotes was determined by normalizing growth of each cell line in the indicated pyrimidine supplement to its growth in the supplement that results in the highest cell density, 100 μm uridine (wild type and Δcps) or 2 mm orotate (Δcps/Δuprt). None, no pyrimidine supplementation. Results depicted are the averages and S.E. (error bars) of three technical replicates.

FIGURE 4.

Growth rates of wild type (■), Δcps (△), Δuprt (♦), and Δcps/Δuprt (○) promastigotes. Logarithmic phase promastigotes were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 parasites/ml in medium supplemented with either 250 μm cytidine for Δcps parasites or 2 mm orotate for Δcps/Δuprt parasites. Parasites were enumerated at 8–16-h intervals for a period of 48 h to determine growth rates. Results depicted are the averages and S.E. (error bars) of three technical replicates.

Growth Inhibition by Uracil as Consequence of Pyrimidine Auxotrophy

The exclusive growth-inhibitory effect of uracil observed with Δcps promastigotes was unanticipated and was therefore examined in more detail as a function of a wide (3 μm to 4 mm) range of uracil concentrations in the culture medium (Fig. 5A). Maximum growth of the Δcps knockout was achieved in medium supplemented with ∼16 μm uracil. However, growth of Δcps promastigotes was inhibited at concentrations of uracil of >125 μm, and essentially no growth was observed by 2 mm (Fig. 5A). A similar pattern of uracil-mediated growth inhibition was observed in a previously isolated pyrimidine auxotroph deficient in UMP synthase (Δumps) (40), whereas wild type promastigotes were impervious to the uracil concentration in the culture medium. To distinguish whether the effects of uracil on Δcps promastigotes were growth-inhibitory or cytotoxic, doubling times of the pyrimidine auxotroph at a range of uracil concentrations were determined. Doubling times of exponentially growing Δcps promastigotes (0–48 h) were determined to be ∼12, ∼17, ∼26, and ∼40 h for uracil concentrations of 100 μm, 500 μm, 2 mm, and 4 mm, respectively (Fig. 5B). Eventually, Δcps promastigotes reached a maximum cell density of ∼6 × 107 cells/ml in 100 μm and 500 μm uracil and peaked at ∼2 × 107 cells/ml in 2 and 4 mm uracil after 10 days of growth (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Uracil hypersensitivity in de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis mutants. A, wild type (■), Δcps (△), and Δumps (○) promastigotes were tested for their ability to grow in media supplemented with various concentrations of uracil. The growth of wild type and mutant promastigotes in each concentration of uracil was normalized to the maximum growth achieved within the assay by that cell line and is represented as the percentage of maximum growth. B, growth rates of Δcps promastigotes in media supplemented with various concentrations of uracil. Logarithmic phase promastigotes were seeded a density of 1 × 106 parasites/ml in medium containing either 100 μm (▴), 500 μm (▾), 2 mm (△), or 4 mm (▿) uracil, and growth of the culture was determined as in Fig. 4. Results depicted are the averages and S.E. (error bars) of three technical replicates.

Uracil and Uridine Incorporation into Phosphorylated Metabolites

The availability of the Δuprt mutant and the requirement of Δcps promastigotes for exogenous pyrimidines afforded an opportunity to dissect the routes of pyrimidine salvage in L. donovani. Incorporation of [5,6-3H]uracil or [5,6-3H]uridine by wild type parasites into phosphorylated anionic metabolites was linear for the duration of the 1-h experiment (Fig. 6). No radiolabel incorporation was observed into Δuprt promastigotes for either the nucleobase or nucleoside (Fig. 6), implicating UPRT as the central pyrimidine salvage enzyme.

FIGURE 6.

Uracil and uridine incorporation by wild type or Δuprt promastigotes. 5 × 107 wild type (■) or Δuprt (♦) parasites were incubated with either 26.3 nm [5,6-3H]uracil (A) or 22.9 nm [5,6-3H]uridine (B) for 1 h. At various time points, 5 × 106 parasites were removed, and incorporation of either [5,6-3H]uracil or [5,6-3H]uridine into the pyrimidine nucleotide pool was determined via a DE81 filter binding assay. The results shown represent the averages and S.E. (error bars) of three technical replicates.

Impact of Genetic Defects in Pyrimidine Metabolism on Infectivity in Mice

To determine the effects of genetic deficiencies in pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage on the ability of L. donovani to establish a visceral infection in mice, parasite burdens in livers and spleens were determined after a 4-week infection with either wild type, null, or add-back parasites. Because of the labor-intensive nature of these mouse infectivity tests, the infectivity assessments of all of the cell lines were performed in separate experiments (Fig. 7). In the first experimental prototype, liver and spleen parasitemias were established for wild type, Δcps, and Δcps[pCPS] parasites (Fig. 7A). In these tests of infectivity, the overall parasite loads were reduced by approximately 2 orders of magnitude in mice infected with Δcps parasites compared with animals injected with the wild type L. donovani counterpart (Fig. 7A). The parasitemia deficit triggered by the Δcps lesion was rescued by episomal complementation of the null mutation because parasite burdens in livers and spleens were effectively equivalent in mice infected with wild type or Δcps[pCPS] promastigotes. Liver parasite loads were slightly higher in mice injected with Δcps[pCPS] add-back promastigotes compared with those injected with wild type parasites. Although interruption of pyrimidine biosynthesis partially compromised the infectivity phenotype of L. donovani, ablation of pyrimidine salvage did not impact parasite loads of L. donovani because equivalent numbers of parasites were recovered from livers and spleens of mice inoculated with either wild type or Δuprt parasites (Fig. 7B). Genetic obliteration of both pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage, however, profoundly compromised the capacity of L. donovani to maintain an infection in mice (Fig. 7B). Indeed, no parasites emerged from 4-week mouse infections with Δcps/Δuprt parasites even when single-cell suspensions were prepared from entire livers and spleens of mice inoculated with the double knockout line. Complementation of either the biosynthetic or salvage pathway lesions in the Δcps/Δuprt line re-established infectivity in a predictable fashion (Fig. 7B). Parasite burdens of mice infected with Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS] parasites were slightly greater in livers and equivalent in spleens to those observed for mice injected with wild type L. donovani, whereas parasitemias of mice inoculated with stationary phase Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT] promastigotes were 2 orders of magnitude lower than those of mice harboring wild type parasites (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Infectivity of L. donovani pyrimidine pathway mutants in a mouse model. Groups of five BALB/c mice were inoculated with 5 × 106 parasites via tail vein injection. After 4 weeks, the liver and spleen of each mouse were harvested, and parasitemias were determined via a limiting dilution assay. A, parasitemias of the livers (black bars) and spleens (gray bars) of BALB/c mice infected with either wild type, Δcps, or Δcps[pCPS] parasites. B, parasitemias of the livers (black bars) and spleens (gray bars) of BALB/c mice infected with either wild type, Δuprt, Δcps/Δuprt, Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS], or Δcps/Δuprt[RP-UPRT] parasites. Error bars, S.E.

Short Term Macrophage and Mouse Infections with Δcps/Δuprt Parasites

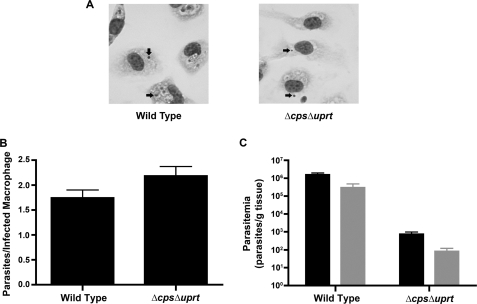

To examine whether the lack of persistent parasites in mice injected with a Δcps/Δuprt inoculum was due to an inability to infect macrophages, wild type and Δcps/Δuprt parasites were incubated with mouse peritoneal macrophages for 6 h, after which intracellular amastigotes were enumerated. This short term infection experiment in vitro revealed that Δcps/Δuprt parasites were capable of entering macrophages and were able to initiate conversion to amastigotes at a rate similar to that of wild type parasites (Fig. 8, A and B). To evaluate the hypothesis that Δcps/Δuprt parasites are capable of infecting but not persisting in mice through a full 4-week infection, the number of tissue-derived amastigotes after a 1-week infection of BALB/c mice with Δcps/Δuprt parasites was also determined. Although the parasite loads of livers and spleens harvested from mice inoculated with Δcps/Δuprt were markedly reduced over those of mice infected with wild type parasites, persistent parasites could still be identified in these short term mouse infections (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Short term in vitro and in vivo infections with wild type and Δcps/Δuprt parasites. A, images of stained murine macrophages after 6 h of infection with either wild type or Δcps/Δuprt parasites. The arrows indicate intracellular amastigotes. Amastigotes within infected macrophages in 50 fields of view were enumerated visually, and the average number of parasites per infected macrophage is depicted in B. C, groups of three BALB/c mice were inoculated with either wild type or Δcps/Δuprt parasites as described in the legend to Fig. 7. After 1 week, the liver and spleen of each mouse was harvested, and the parasitemias in the livers (black bars) and spleens (gray bars) were determined via a limiting dilution assay. Error bars, S.E.

DISCUSSION

Unlike the purine salvage pathway, which serves as the sole mechanism by which protozoan parasites of humans manufacture purine nucleotides, Leishmania synthesize pyrimidine nucleotides via both biosynthesis from amino acids and one-carbon compounds and via salvage of preformed host pyrimidine bases and nucleosides (1). This pyrimidine prototrophy is observed among all trypanosomatid parasites that infect humans, although several genera of protozoan parasites lack pyrimidine biosynthetic capacity (1). The relative contributions of pyrimidine biosynthesis and salvage to survival, growth, and infectivity of Leishmania parasites, however, have not been evaluated previously. In order to test the functional roles and contributions of the biosynthetic and salvage pathways to pyrimidine homeostasis in L. donovani, Δcps, Δuprt, and Δcps/Δuprt mutants were created by double targeted gene replacement strategies. The consequent pyrimidine auxotrophy and conditionally lethal growth phenotype of the Δcps single knockout (Fig. 3B) indicate that the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway is essential to the promastigote stage of L. donovani under the experimentally delimited laboratory conditions under which these experiments were carried out. Restoration of pyrimidine prototrophy in both the Δcps[pCPS] and Δcps/Δuprt[RP-CPS] add-back lines proved that the Δcps auxtrophic phenotype is due to the genetic defect and not to some secondary genetic modification. Whether the conditionally lethal phenotype of the Δcps null mutant would affect survival, growth, and development in the insect vector under field conditions is, of course, unknown and depends upon the pyrimidine content of the insect milieu in which the promastigote subsists.

The pyrimidine auxotrophy induced by the Δcps lesion in L. donovani could be circumvented by micromolar concentrations of uracil, uridine, cytidine, and their deoxyribonucleoside counterparts. Dihydroorotate and orotate could also bypass a Δcps mutation but only at millimolar concentrations (Fig. 3B). The discrepancies in the concentrations of dihydroorotate and orotate and other pyrimidines required to rescue the conditionally lethal Δcps growth phenotype can be ascribed to permeability differences, because dihydroorotate and orotate are both negatively charged, or to variations in the rate by which orotate and uracil are incorporated into nucleotides via orotate phosphoribosyltransferase and UPRT, respectively (see Fig. 1). Thymidine, thymine, and cytosine did not rescue the auxotrophy of the Δcps strain because the deoxyribonucleoside cannot meet the parasite's requirement for ribonucleotides, and the two nucleobases are not actively transported (5) and cannot be phosphoribosylated to the nucleotide level. Because the genomes of Leishmania species encode UPRT, uridine hydrolases, uridine phosphorylase, and cytidine deaminase, it is reasonable to infer that cytidine and deoxycytidine are deaminated to their uridine and deoxyuridine counterparts, respectively, uridine and deoxyuridine are cleaved to uracil, and uracil is phosphoribosylated via UPRT and incorporated into the parasite pyrimidine nucleotide pool (see Fig. 1). However, leishmanial genomes accommodate a homolog to the mammalian uridine-cytidine kinase, but most of these sequences bear frameshift mutations that disintegrate the open reading frame, implying that they are pseudogenes (19). The inference that all pyrimidine salvage is funneled through UPRT was substantiated genetically because the pyrimidine auxotrophy of the Δcps/Δuprt double knockout could not be circumvented with uracil, uridine, deoxyuridine, cytidine, or deoxycytidine (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, Δuprt promastigotes cannot incorporate radiolabeled uracil or uridine into nucleotides (Fig. 6), demonstrating that the uridine kinase homolog in the L. donovani genome is vestigial. Thus, UPRT is the only route by which uracil and preformed pyrimidine nucleosides can be salvaged by L. donovani, although high concentrations of exogenous dihydroorotate and orotate can be incorporated into UMP by the de novo pathway enabling the selection and survival of the Δcps/Δuprt double knockout (see Fig. 1).

The collateral supersensitivity of the Δcps null mutant to exogenous uracil is intriguing, especially because the nucleobase is nontoxic to wild type cells (Figs. 3A and 5A). This unusual growth susceptibility is specific to the nucleobase and not observed when Δcps promastigotes are grown in medium supplemented with a pyrimidine ribonucleoside or deoxyribonucleoside. Episomal complementation of the Δcps mutant in the Δcps[pCPS] line resulted in abolition of the uracil sensitivity, proving that the unusual growth response to uracil is triggered by the genetic lesion (data not shown). An analogous genetic replacement of the gene copies encoding the fifth and sixth steps of the de novo pathway, UMPS, also sensitizes L. donovani promastigotes to millimolar concentrations of uracil, demonstrating that the growth vulnerability phenotype is not peculiar to the Δcps lesion but, rather, is a property common to mutants incapable of de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis. Intriguingly, a similar hypersensitivity to high uracil concentrations has been noted in T. cruzi (22) and T. gondii (47) upon genetic ablation of de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis, intimating a shared mechanism of growth inhibition.

Despite their pyrimidine auxotrophy, Δcps L. donovani are only partially attenuated in their capacity to establish visceral infections in mice (Fig. 7A), indicating that pyrimidine salvage within the phagolysosome of the host macrophage is sufficient for amastigote survival and maintenance. Because uracil incorporation by mammalian cells is negligible (48, 49), steady-state pools of uracil are presumed to be low. Thus, the immediate source of salvageable pyrimidines in the phagolysosome is most likely the nucleosides uridine and cytidine. Because these nucleosides are funneled through uracil in L. donovani, a conditionally lethal Δcps/Δuprt double mutant is completely attenuated, and no persistence is observed in livers or spleens 4 weeks postinfection. The retention of virulence by Δcps L. donovani was unanticipated, especially considering that Fox and Bzik (47) have established that a Δcps mutant of T. gondii, another intracellular protozoan parasite that causes toxoplasmosis in humans, is effectively avirulent, not only in immunocompetent BALB/c mice but also in interferon-γ-deficient mice that cannot resist infection even by normally avirulent T. gondii strains (50). The discrepancy in the virulence characteristics between Δcps L. donovani and Δcps T. gondii can be ascribed either to variations in the microenvironments of the macrophage lysosome and the parasitopherous vacuole in which L. donovani and T. gondii reside, respectively, or to dissimilarities in the complement or properties of pyrimidine salvage and interconversion enzymes expressed by the two parasites.

Although the intergenic regions of the pyrimidine biosynthesis locus of L. donovani were not sequenced in this study, all five genes were syntenic, as expected from the mapped pyrimidine loci of Leishmania species (19) and T. cruzi (15), because they were physically co-localized to a single cosmid DNA. T. brucei, however, exhibits a loss of synteny at the DHO locus (16). To our knowledge, the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway genes represent the only example of microsyntenic clustering of an entire biosynthetic pathway in trypanosomatids. Conversely, UPRT as well as the pyrimidine nucleoside interconversion enzymes are non-syntenic with the biosynthetic cluster and with each other. Furthermore, our limited analysis revealed that CPS and DHODH were located at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively, of the pyrimidine biosynthesis locus, similar to other Leishmania species and T. cruzi, whose genomes have been sequenced, suggesting shared synteny of the entire locus. Bioinformatic analysis also revealed the presence of a gene encoding a hypothetical protein and several histone genes within the pyrimidine clusters of L. major, L. mexicana, and L. infantum (19). Whether other essential genes have integrated into the pyrimidine gene cluster in L. donovani is currently being investigated via attempts to delete the entire complement of pyrimidine biosynthesis enzymes by targeted gene replacement.

The L. donovani CPS protein displays the same structural features described by Aoki and co-workers (3, 15) for the CPS proteins from Crithidia fasciculata, L. mexicana, and T. cruzi. Several of these shared features distinguish the L. donovani and other trypanosomatid CPS proteins from their mammalian and prokaryotic counterparts. In contrast to prokaryotes, where glutamine amidotransferase and CPS activities are found as distinct polypeptides, the L. donovani CPS accommodates an NH2-terminal glutamine amidotransferase domain separated by a short polylinker region from the catalytic CPS domain. Moreover, the L. donovani CPS is a genetically and biochemically distinct protein from ACT and DHO, whereas these enzymatic activities are encoded as a single trifunctional polypeptide in mammalian cells (44, 45) as well as in Dictyostelium discoideum (51) and Drosophila melanogaster (52). Other L. donovani pyrimidine biosynthesis enzymes also exhibit signature trypanosomatid distinctions from their mammalian counterparts, including (i) a bifunctional UMPS polypeptide in which the two distinct enzymatic entities are arranged in the reverse order of the bifunctional mammalian UMPS protein and that contains a COOH-terminal peroxisomal targeting signal (53, 54) that directs targeting of proteins to the glycosome, a unique microbody of trypanosomatids (55, 56); (ii) monofunctional ACT and DHO enzymes; and (iii) a DHODH that is analogous to the fumarate-dependent enzyme of T. brucei (20, 21).

This investigation offers the first functional analysis of the pyrimidine biosynthetic and salvage pathways of Leishmania and delineates the relative contributions of the two pathways to pyrimidine homeostasis, both in vitro and in vivo. These data indicate that a lesion in the first enzyme of the de novo pathway is lethal to the promastigote under pyrimidine-free growth conditions, but this lethality can be circumvented by a battery of exogenous pyrimidines that are channeled through UPRT into the parasite pyrimidine nucleotide pool. Conversely, the L. donovani amastigote can avail itself of its pyrimidine salvage machinery in order to survive and proliferate in mice because a genetic block in CPS does not produce an attenuated phenotype, although total parasite burdens are somewhat reduced compared with mice inoculated with wild type parasites. Genetic obliteration of pyrimidine salvage in the Δcps genetic background results in a completely attenuated infectivity phenotype that can be genetically reversed by functional restoration of either the biosynthetic or salvage pathway. These data imply, therefore, that targeting the functionally redundant pyrimidine pathway of Leishmania with chemotherapeutics would require simultaneous inhibition of both biosynthesis and salvage. Furthermore, the lack of persistence of the Δcps/Δuprt strain in mice after a 4-week infection could be advantageous in implementing a live attenuated parasite vaccination strategy for leishmaniasis, although low levels of persistence are thought to be necessary for producing T-cell protective immunity to subsequent challenge by Leishmania (46, 57, 58). Whether Δcps/Δuprt parasites persist or can be made to persist for a long enough time period to trigger long term protective immunity remains to be investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Nicola Carter for many insightful discussions during the course of this work.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIAID, Grant AI023682.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Fig. S1.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) JN882601.

P. Yates and B. Ullman, unpublished data.

D. R. Soysa and P. Yates, manuscript in preparation.

- CPS

- carbamoyl phosphate synthetase

- UPRT

- uracil phosphoribosyltransferase

- DHODH

- dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

- ACT

- aspartate carbamoyltransferase

- DHO

- dihydroorotase

- UMPS

- UMP synthase

- HYG

- hygromycin resistance cassette

- NEO

- G418 resistance cassette

- PAC

- puromycin resistance cassette

- RRNA

- ribosomal RNA

- DME-L

- Dulbecco's Modified Eagle-Leishmania medium.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carter N., Rager N, Ullman B. (2003) Purine and pyrimidine transport and metabolism. in Molecular and Medical Parasitology (Marr J. J., Nilsen T. W., Komuniecki R., eds) pp. 197–223, Academic Press Ltd., London [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hammond D. J., Gutteridge W. E. (1980) Enzymes of pyrimidine biosynthesis in Trypanosoma cruzi. FEBS Lett. 118, 259–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nara T., Gao G., Yamasaki H., Nakajima-Shimada J., Aoki T. (1998) Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase II in kinetoplastids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1387, 462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aronow B., Kaur K., McCartan K., Ullman B. (1987) Two high affinity nucleoside transporters in Leishmania donovani. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 22, 29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papageorgiou I. G., Yakob L., Al Salabi M. I., Diallinas G., Soteriadou K. P., De Koning H. P. (2005) Identification of the first pyrimidine nucleobase transporter in Leishmania. Similarities with the Trypanosoma brucei U1 transporter and antileishmanial activity of uracil analogues. Parasitology 130, 275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hammond D. J., Gutteridge W. E. (1982) UMP synthesis in the kinetoplastida. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 718, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi W., Schramm V. L., Almo S. C. (1999) Nucleoside hydrolase from Leishmania major. Cloning, expression, catalytic properties, transition state inhibitors, and the 2.5-Å crystal structure. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21114–21120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hassan H. F., Coombs G. H. (1986) A comparative study of the purine- and pyrimidine-metabolizing enzymes of a range of trypanosomatids. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 84, 219–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beverley S. M., Ellenberger T. E., Cordingley J. S. (1986) Primary structure of the gene encoding the bifunctional dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase of Leishmania major. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 2584–2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ivanetich K. M., Santi D. V. (1990) Bifunctional thymidylate synthase-dihydrofolate reductase in protozoa. FASEB J. 4, 1591–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vasudevan G., Carter N. S., Drew M. E., Beverley S. M., Sanchez M. A., Seyfang A., Ullman B., Landfear S. M. (1998) Cloning of Leishmania nucleoside transporter genes by rescue of a transport-deficient mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9873–9878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vasudevan G., Ullman B., Landfear S. M. (2001) Point mutations in a nucleoside transporter gene from Leishmania donovani confer drug resistance and alter substrate selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6092–6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cui L., Rajasekariah G. R., Martin S. K. (2001) A nonspecific nucleoside hydrolase from Leishmania donovani. Implications for purine salvage by the parasite. Gene 280, 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garrett C. E., Coderre J. A., Meek T. D., Garvey E. P., Claman D. M., Beverley S. M., Santi D. V. (1984) A bifunctional thymidylate synthetase-dihydrofolate reductase in protozoa. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 11, 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gao G., Nara T., Nakajima-Shimada J., Aoki T. (1999) Novel organization and sequences of five genes encoding all six enzymes for de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis in Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berriman M., Ghedin E., Hertz-Fowler C., Blandin G., Renauld H., Bartholomeu D. C., Lennard N. J., Caler E., Hamlin N. E., Haas B., Böhme U., Hannick L., Aslett M. A., Shallom J., Marcello L., Hou L., Wickstead B., Alsmark U. C., Arrowsmith C., Atkin R. J., Barron A. J., Bringaud F., Brooks K., Carrington M., Cherevach I., Chillingworth T. J., Churcher C., Clark L. N., Corton C. H., Cronin A., Davies R. M., Doggett J., Djikeng A., Feldblyum T., Field M. C., Fraser A., Goodhead I., Hance Z., Harper D., Harris B. R., Hauser H., Hostetler J., Ivens A., Jagels K., Johnson D., Johnson J., Jones K., Kerhornou A. X., Koo H., Larke N., Landfear S., Larkin C., Leech V., Line A., Lord A., Macleod A., Mooney P. J., Moule S., Martin D. M., Morgan G. W., Mungall K., Norbertczak H., Ormond D., Pai G., Peacock C. S., Peterson J., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Rajandream M. A., Reitter C., Salzberg S. L., Sanders M., Schobel S., Sharp S., Simmonds M., Simpson A. J., Tallon L., Turner C. M., Tait A., Tivey A. R., Van Aken S., Walker D., Wanless D., Wang S., White B., White O., Whitehead S., Woodward J., Wortman J., Adams M. D., Embley T. M., Gull K., Ullu E., Barry J. D., Fairlamb A. H., Opperdoes F., Barrell B. G., Donelson J. E., Hall N., Fraser C. M., Melville S. E., El-Sayed N. M. (2005) The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 309, 416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Sayed N. M., Myler P. J., Bartholomeu D. C., Nilsson D., Aggarwal G., Tran A. N., Ghedin E., Worthey E. A., Delcher A. L., Blandin G., Westenberger S. J., Caler E., Cerqueira G. C., Branche C., Haas B., Anupama A., Arner E., Aslund L., Attipoe P., Bontempi E., Bringaud F., Burton P., Cadag E., Campbell D. A., Carrington M., Crabtree J., Darban H., da Silveira J. F., de Jong P., Edwards K., Englund P. T., Fazelina G., Feldblyum T., Ferella M., Frasch A. C., Gull K., Horn D., Hou L., Huang Y., Kindlund E., Klingbeil M., Kluge S., Koo H., Lacerda D., Levin M. J., Lorenzi H., Louie T., Machado C. R., McCulloch R., McKenna A., Mizuno Y., Mottram J. C., Nelson S., Ochaya S., Osoegawa K., Pai G., Parsons M., Pentony M., Pettersson U., Pop M., Ramirez J. L., Rinta J., Robertson L., Salzberg S. L., Sanchez D. O., Seyler A., Sharma R., Shetty J., Simpson A. J., Sisk E., Tammi M. T., Tarleton R., Teixeira S., Van Aken S., Vogt C., Ward P. N., Wickstead B., Wortman J., White O., Fraser C. M., Stuart K. D., Andersson B. (2005) The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science 309, 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ivens A. C., Peacock C. S., Worthey E. A., Murphy L., Aggarwal G., Berriman M., Sisk E., Rajandream M. A., Adlem E., Aert R., Anupama A., Apostolou Z., Attipoe P., Bason N., Bauser C., Beck A., Beverley S. M., Bianchettin G., Borzym K., Bothe G., Bruschi C. V., Collins M., Cadag E., Ciarloni L., Clayton C., Coulson R. M., Cronin A., Cruz A. K., Davies R. M., De Gaudenzi J., Dobson D. E., Duesterhoeft A., Fazelina G., Fosker N., Frasch A. C., Fraser A., Fuchs M., Gabel C., Goble A., Goffeau A., Harris D., Hertz-Fowler C., Hilbert H., Horn D., Huang Y., Klages S., Knights A., Kube M., Larke N., Litvin L., Lord A., Louie T., Marra M., Masuy D., Matthews K., Michaeli S., Mottram J. C., Müller-Auer S., Munden H., Nelson S., Norbertczak H., Oliver K., O'neil S., Pentony M., Pohl T. M., Price C., Purnelle B., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Reinhardt R., Rieger M., Rinta J., Robben J., Robertson L., Ruiz J. C., Rutter S., Saunders D., Schäfer M., Schein J., Schwartz D. C., Seeger K., Seyler A., Sharp S., Shin H., Sivam D., Squares R., Squares S., Tosato V., Vogt C., Volckaert G., Wambutt R., Warren T., Wedler H., Woodward J., Zhou S., Zimmermann W., Smith D. F., Blackwell J. M., Stuart K. D., Barrell B., Myler P. J. (2005) The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science 309, 436–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peacock C. S., Seeger K., Harris D., Murphy L., Ruiz J. C., Quail M. A., Peters N., Adlem E., Tivey A., Aslett M., Kerhornou A., Ivens A., Fraser A., Rajandream M. A., Carver T., Norbertczak H., Chillingworth T., Hance Z., Jagels K., Moule S., Ormond D., Rutter S., Squares R., Whitehead S., Rabbinowitsch E., Arrowsmith C., White B., Thurston S., Bringaud F., Baldauf S. L., Faulconbridge A., Jeffares D., Depledge D. P., Oyola S. O., Hilley J. D., Brito L. O., Tosi L. R., Barrell B., Cruz A. K., Mottram J. C., Smith D. F., Berriman M. (2007) Comparative genomic analysis of three Leishmania species that cause diverse human disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 839–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Annoura T., Nara T., Makiuchi T., Hashimoto T., Aoki T. (2005) The origin of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase genes of kinetoplastids, with special reference to their biological significance and adaptation to anaerobic, parasitic conditions. J. Mol. Evol. 60, 113–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arakaki T. L., Buckner F. S., Gillespie J. R., Malmquist N. A., Phillips M. A., Kalyuzhniy O., Luft J. R., Detitta G. T., Verlinde C. L., Van Voorhis W. C., Hol W. G., Merritt E. A. (2008) Characterization of Trypanosoma brucei dihydroorotate dehydrogenase as a possible drug target. Structural, kinetic, and RNAi studies. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 37–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hashimoto M., Morales J., Fukai Y., Suzuki S., Takamiya S., Tsubouchi A., Inoue S., Inoue M., Kita K., Harada S., Tanaka A., Aoki T., Nara T. (2012) Critical importance of the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway for Trypanosoma cruzi growth in the mammalian host cell cytoplasm. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 1002–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boitz J. M., Ullman B. (2006) A conditional mutant deficient in hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase and xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase validates the purine salvage pathway of Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16084–16089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boitz J. M., Ullman B. (2006) Leishmania donovani singly deficient in HGPRT, APRT, or XPRT are viable in vitro and within mammalian macrophages. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 148, 24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hwang H. Y., Gilberts T., Jardim A., Shih S., Ullman B. (1996) Creation of homozygous mutants of Leishmania donovani with single targeting constructs. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30840–30846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hwang H. Y., Ullman B. (1997) Genetic analysis of purine metabolism in Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 19488–19496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iovannisci D. M., Goebel D., Allen K., Kaur K., Ullman B. (1984) Genetic analysis of adenine metabolism in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Evidence for diploidy at the adenine phosphoribosyltransferase locus. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 14617–14623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iovannisci D. M., Kaur K., Young L., Ullman B. (1984) Genetic analysis of nucleoside transport in Leishmania donovani. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 1013–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cruz A., Coburn C. M., Beverley S. M. (1991) Double targeted gene replacement for creating null mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 7170–7174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Freedman D. J., Beverley S. M. (1993) Two more independent selectable markers for stable transfection of Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62, 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ha D. S., Schwarz J. K., Turco S. J., Beverley S. M. (1996) Use of the green fluorescent protein as a marker in transfected Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 77, 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goyard S., Segawa H., Gordon J., Showalter M., Duncan R., Turco S. J., Beverley S. M. (2003) An in vitro system for developmental and genetic studies of Leishmania donovani phosphoglycans. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 130, 31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dwyer D. M. (1972) A monophasic medium for cultivating Leishmania donovani in large numbers. J. Parasitol. 58, 847–848 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holbrook T. W., Palczuk N. C. (1975) Comparison of two geographic strains of Leishmania donovani by resistance of mice to superinfection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 24, 704–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Debrabant A., Joshi M. B., Pimenta P. F., Dwyer D. M. (2004) Generation of Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes. Their growth and biological characteristics. Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carter N. S., Yates P. A., Gessford S. K., Galagan S. R., Landfear S. M., Ullman B. (2010) Adaptive responses to purine starvation in Leishmania donovani. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 92–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iovannisci D. M., Ullman B. (1983) High efficiency plating method for Leishmania promastigotes in semidefined or completely defined medium. J. Parasitol. 69, 633–636 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mikus J., Steverding D. (2000) A simple colorimetric method to screen drug cytotoxicity against Leishmania using the dye Alamar Blue. Parasitol. Int. 48, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fulwiler A. L., Soysa D. R., Ullman B., Yates P. A. (2011) A rapid, efficient and economical method for generating leishmanial gene targeting constructs. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 175, 209–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. French J. B., Yates P. A., Soysa D. R., Boitz J. M., Carter N. S., Chang B., Ullman B., Ealick S. E. (2011) The Leishmania donovani UMP synthase is essential for promastigote viability and has an unusual tetrameric structure that exhibits substrate-controlled oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20930–20941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Robinson K. A., Beverley S. M. (2003) Improvements in transfection efficiency and tests of RNA interference (RNAi) approaches in the protozoan parasite Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 128, 217–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Boitz J. M., Yates P. A., Kline C., Gaur U., Wilson M. E., Ullman B., Roberts S. C. (2009) Leishmania donovani ornithine decarboxylase is indispensable for parasite survival in the mammalian host. Infect. Immun. 77, 756–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Buffet P. A., Sulahian A., Garin Y. J., Nassar N., Derouin F. (1995) Culture microtitration. A sensitive method for quantifying Leishmania infantum in tissues of infected mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39, 2167–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stark G. R., Wahl G. M. (1984) Gene amplification. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53, 447–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wahl G. M., Padgett R. A., Stark G. R. (1979) Gene amplification causes overproduction of the first three enzymes of UMP synthesis in N-(phosphonacetyl)-l-aspartate-resistant hamster cells. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 8679–8689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brodskyn C., Beverley S. M., Titus R. G. (2000) Virulent or avirulent (dhfr−ts−) Leishmania major elicit predominantly a type-1 cytokine response by human cells in vitro. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 119, 299–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fox B. A., Bzik D. J. (2002) De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 415, 926–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pfefferkorn E. R., Pfefferkorn L. C. (1977) Specific labeling of intracellular Toxoplasma gondii with uracil. J. Protozool. 24, 449–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schneider E. L., Stanbridge E. J., Epstein C. J. (1974) Incorporation of [3H]uridine and [3H]uracil into RNA. A simple technique for the detection of mycoplasma contamination of cultured cells. Exp. Cell Res. 84, 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suzuki Y., Orellana M. A., Schreiber R. D., Remington J. S. (1988) Interferon-γ. The major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science 240, 516–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Faure M., Camonis J. H., Jacquet M. (1989) Molecular characterization of a Dictyostelium discoideum gene encoding a multifunctional enzyme of the pyrimidine pathway. Eur. J. Biochem. 179, 345–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Freund J. N., Jarry B. P. (1987) The rudimentary gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes four enzymic functions. J. Mol. Biol. 193, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Blattner J., Swinkels B., Dörsam H., Prospero T., Subramani S., Clayton C. (1992) Glycosome assembly in trypanosomes. Variations in the acceptable degeneracy of a COOH-terminal microbody targeting signal. J. Cell Biol. 119, 1129–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sommer J. M., Cheng Q. L., Keller G. A., Wang C. C. (1992) In vivo import of firefly luciferase into the glycosomes of Trypanosoma brucei and mutational analysis of the C-terminal targeting signal. Mol. Biol. Cell 3, 749–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Opperdoes F. R. (1987) Compartmentation of carbohydrate metabolism in trypanosomes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41, 127–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Opperdoes F. R. (1988) Glycosomes may provide clues to the import of peroxisomal proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 13, 255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Breton M., Tremblay M. J., Ouellette M., Papadopoulou B. (2005) Live nonpathogenic parasitic vector as a candidate vaccine against visceral leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 73, 6372–6382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park A. Y., Hondowicz B. D., Scott P. (2000) IL-12 is required to maintain a Th1 response during Leishmania major infection. J. Immunol. 165, 896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.