Abstract

Biosystems integration into an organic field-effect transistor (OFET) structure is achieved by spin coating phospholipid or protein layers between the gate dielectric and the organic semiconductor. An architecture directly interfacing supported biological layers to the OFET channel is proposed and, strikingly, both the electronic properties and the biointerlayer functionality are fully retained. The platform bench tests involved OFETs integrating phospholipids and bacteriorhodopsin exposed to 1–5% anesthetic doses that reveal drug-induced changes in the lipid membrane. This result challenges the current anesthetic action model relying on the so far provided evidence that doses much higher than clinically relevant ones (2.4%) do not alter lipid bilayers’ structure significantly. Furthermore, a streptavidin embedding OFET shows label-free biotin electronic detection at 10 parts-per-trillion concentration level, reaching state-of-the-art fluorescent assay performances. These examples show how the proposed bioelectronic platform, besides resulting in extremely performing biosensors, can open insights into biologically relevant phenomena involving membrane weak interfacial modifications.

Keywords: organic electronics, analytical bioassay, electronic biodetection

Integration of membranes and proteins into electronic devices (1, 2) involves a cross-disciplinary effort aiming at the full exploitation of a biomolecule specific functionality for advanced bioelectronic applications (1, 3). Membrane proteins, such as ion pumps or receptors, but also antibodies or enzymes, can be exploited as recognition elements in electronic sensors. So far, the preferred choice has been directed toward field-effect transistors comprising a single silicon nanowire (4–6), carbon (7), or polypyrrole (8) nanotubes as channel material. The biological system deputed to the biorecognition is anchored to the nanostructured semiconductor. Electrochemical gating is mostly adopted, although back gating through oxide dielectrics is also used. Nanostructured channel materials allow both the close coupling between the biorecognition event and the field-induced transport, along with a conveniently low interaction cross-section, both contributing to achieve extremely sensitive responses (6, 8). The main drawbacks of these achievements, otherwise challenging and fascinating, are the technological issues inherent to nanodevice fabrication and low-cost production. In addition, the electrochemically gated field-effect transistors (FET) need for a reference electrode affects, as yet, their full integration in complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) (9).

Organic planar field-effect transistors (OFETs) can be a viable alternative. In such submillimeter scale architectures, current amplification occurs at the interface between a gate dielectric and the organic semiconductor where the 2D field-effect transport occurs (10). Such devices are compatible with ink-jet printing manufacturing. Their implementation in organic CMOS circuits on plastic and paper substrates (11), as well as on exotic ones (12), has been proposed recently. This technology paves the way to the development of low-cost printable bioelectronic systems whose first proof is represented by the organic electronic ion pump used to release neurotransmitters in vivo to stimulate cochlear cells (13). Direct interfacing of biomolecules with an electronic transducer opens to wider scenarios and an interesting approach encompasses the use of DNA (14) as gate dielectric material or silk for conformal biointegrated electronics (15). Likewise, the modification of a silica surface with quartz binding polypeptides has been proposed to control the OFET turn-on-bias (threshold voltage, VT) (16).

Several applications of OFETs as sensors have been already proposed (11, 17). One of the most relevant features is the recently proven field-effect enhanced selectivity that allows for chiral differential detection at unprecedented low concentrations (18). OFET sensors can also work in water (19, 20) as well as in the subvolt bias regime (20, 21). Specificity relies on device structures that either involve enzymatic reactions [with FET electrochemical transduction (22)] or two-layer architectures, including a bioactive film deposited on top of the channel organic semiconductor (18, 23, 24). The reference electrode issue remains in electrochemical OFETs, while in the two-layer architecture the recognition event takes place far from the semiconductor/dielectric interface affecting the 2D electronic transport only indirectly (10).

Results and Discussion

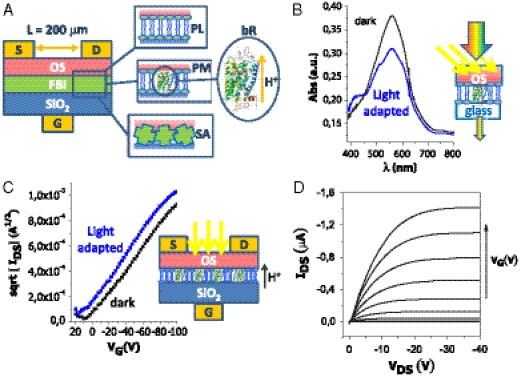

This report focuses on the investigation of a functional biosystem through an electronic probe constituted by an OFET channel. The bioelectronic OFET proposed comprises an interlayer of a functional biosystem deposited between the gate dielectric and the organic semiconductor. This is implemented in the functional biointerlayer organic field-effect transistors (FBI-OFETs) platform whose structure is reported in Fig. 1A. This is an unconventional approach needing a wide assessment. To this aim, devices embedding different biosystems have been realized, characterized, and studied. Three different biosystems have been therefore chosen as prototypes for membranes (i), membrane proteins (ii), and hydrophilic proteins (iii). Specifically, FBIs are: a phospholipid (PL) bilayer (i), a purple membrane (PM) film (ii), and a streptavidin (SA) protein layer (iii).

Fig. 1.

OFET fabrication, FBI integration and bioactivity. (A) Schematic illustration of the FBI-OFET, see Methods section for details. Sketches for the three different FBI structures investigated are shown. (B) The Purple Membrane (PM)—P3HT on glass architecture, reproducing the PM-P3HT interface in the OFET, is used to prove the retained light-driven bR bioactivity. The black curve is the absorption spectrum of the PM-P3HT measured in the dark, while the blue curve is measured under continuous illumination with an halogen lamp filtered through a yellow filter (λ > 500 nm, power density on the film = 1.86 mW/cm2). (C) PM FBI-OFET sqrt(IDS) - VG curves at VDS = -80 V (gate dielectric being SiO2 300 nm thick) measured in the dark (black curve) or under yellow light illumination (blue curve). Illumination conditions as in B. (D) Current-voltage characteristics for a PL FBI-OFET (gate dielectric being a 100 nm thick SiO2 and the gate-bias VG ranging from 0 and -40 V). The gate dielectric capacitance layer was not affected by the presence of the high capacitance PL ultrathin film.

The phosphatidylcholine PLs are one of the major components in all cell membranes and are permeable to volatile anesthetics (25). The PM, taken from the cell membrane of the bacterium Halobacterium salinarum, is constituted of a PL bilayer including the sole bacteriorhodopsin (bR) protein (1). It exists as a highly ordered membrane structure with an extremely low PL/protein ratio that confers exceptional stability against thermal and chemical degradation (26). The PM explicates its bioactivity when exposed to light (1) or to other external stimuli, such as general anesthetics, that are capable to modify the bR local pKa values (27, 28).

Streptavidin is a hydrophilic tetrameric protein with an extraordinarily high affinity for biotin (dissociation constant on the order of fM) which makes it extremely interesting as a biosensor technology bench test (29).

Other membrane proteins, such as odor receptors, are inherently robust (8) and can be suitable for integration into an OFET channel, likewise hydrophilic biosystems, such as antibodies, DNA, or enzymes.

The details of the FBI-OFET devices fabrication procedure and layers morphological and structural characterizations are reported in Materials and Methods and SI Text sections. Only a few of the most relevant aspects of the device structure reported in Fig. 1A are itemized in the following:

All the biolayers were deposited by very slow speed spin coating from water directly on the gate dielectric (SiO2). Other deposition techniques can be implemented, such as electrostatic or Langmuir–Blodgett, layer-by-layer assembly, as well as by chemisorption.

The p-type organic semiconductor (OS) is regioregular poly-3-hexylthiophene (P3HT) deposited by spin coating from a chloroform solution, directly on top of each FBI layer. After deposition, the pristine P3HT exhibits the expected grain morphology (see Atomic Force Micrographs—AFMs—in Fig. S1A) with voids between the grains reaching dimensions of several tens of nanometers. This ensures an excellent overall coverage of the FBI layer, along with suitable percolation paths to the underneath bioactive layer. This is supported by the P3HT-FBIs bilayers’ AFMs that exhibit larger grains, ascribable to the underneath FBI morphology, homogeneously covered with a draping layer characterized by a granular texture typical of the OS (Fig. S1 B and D).

The P3HT deposition onto the dry PL layer does not completely remove the phospholipids, although both are soluble in chloroform as proven by the photoluminescence spectrum exhibiting contributions from both the fluorophore-labeled PL and the semiconductor itself (Fig. S2). The stacking structure with the PL layer confined underneath the OS was assessed by angle-resolved XPS analysis (Fig. S3). X-ray specular reflectivity data shows that a ca. 6 nm thick film, constituted of, at most, a single PL bilayer (Fig. S4), is found underneath the OS.

The PM layer, with a thickness of approximately 1 μm, is not affected by the OS deposition too, as assessed by optical spectroscopy (vide infra) and grazing-incidence-small-angle X-ray scattering—GISAXS (Fig. S5). The latter indicates that the PM film is composed of about 200 lamellae stacked parallel to the SiO2 surface, with each lamella being oriented randomly upward or downward with respect to the substrate. Accordingly, the bRs (contained in PMs) expose the cytoplasmic (CP) or the extracellular (EC) side randomly to the OS interface.

Assessing Interlayer BioActivity After Integration in an OFET.

Before proceeding in the study of the FBIs’ interface properties by means of electronic assessment, it is critically important to demonstrate that the PM and SA interlayers retain their bioactivity after integration into the OFET. This is not trivial, considering that the elicited biolayers are here subjected to processing, such as, for instance, the OS spreading from chloroform, that could likely deteriorate their functionality. PL layers, although critically important in most biosystems, do not explicate a clear-cut bioactivity; therefore, they will not be considered in this section.

The easiest way to assess the bR bioactivity is to investigate the changes occurring in the PM (containing the bR molecules) absorption spectrum upon yellow light illumination. The bR is a light-driven ion pump whose biological activity is explicated by protons driven from the CP to the EC side of the bacterial membrane as photons are absorbed. Associated to this process, the PM color turns from purple to yellow. To optically investigate the PM-P3HT interface, the bilayer was deposited on a glass slide. The visible absorption spectra of the PM-P3HT sample on glass, in the dark and in the light, are shown in Fig. 1B. The spectrum measured in the dark is dominated by the absorption peak at approximately 570 nm ascribed to the bR’s all-trans retinal. Upon exposure to yellow light (λ > 500 nm), the retinal switches to the 13-cis-configuration, triggering the proton translocation cycle (1). Eventually, a steady state (with an absorption maximum at 410 nm) is reached upon continuous illumination. The PM-P3HT on glass absorbance spectrum under yellow light indeed exhibits a pronounced bleaching at 570 nm with the appearance of a band at 410 nm, thus proving that the bR molecules in the PM-P3HT system are still bioactive, namely capable to generate a proton flux. To prove the bR retained its bioactivity also under transistor operation, the PM FBI-OFET source-drain current (IDS) vs. the gate bias (VG) transfer characteristics where measured in the dark and under illumination (Fig. 1C). At all gate biases, the current flowing between source and drain contacts (OFET channel region) increases upon illumination. Such an effect was not seen on the bare P3HT OFET. Photocurrents in bR are ascribed to H+ pumped upon illumination (30). However, as the bRs are randomly oriented, a negligible net current is generally reported (27). In the PM FBI-OFET, however, the presence of the gate bias blocks the H+ flux in the direction opposite to the applied field, leading to a net proton injection into the OS. Eventually, IDS increases, VT shifts toward positive values (more than 10 V in Fig. 1C), while mobility stays constant. All together, these evidences support the occurrence of a proton injection into the OFET channel. Importantly, this current increase occurs only when the device is excited with photons triggering the proton pumping in the bRs. These evidences support a model of photo-generated H+ ions injected by the bRs directly into the OFET channel, proving that the embedded PM is still bioactive and that a direct electronic coupling between the biolayer and the OFET channel is achieved.

Also, the SA layer bioactivity is not affected when subjected to the relevant FBI-OFET device fabrication processing. Specifically, the bare SA capability to bind biotin molecules remains unaffected by chloroform spreading, as demonstrated by the results reported in the SA Functionality After Chloroform Spin-Spreading section of SI Text and Fig. S6. In the case of the SA layer embedded into the OFET, the retained bioactivity is proven by the device capability to perform selective biotin sensing as proven by the data discussed in the paragraph of the above mentioned section.

FBI-OFET Field-Effect Performance Level.

The FBI layers retain their bioactivity while integrated in the OFET structure. Even more strikingly, however, the FBI-OFETs hold also good field-effect performance, as shown by the current-voltage characteristics of the PL FBI-OFET reported in Fig. 1D. IDS exhibits linear and saturation regions as the source-drain bias (VDS) is swept, showing also good modulation with VG, while the leakage current at zero VDS, plaguing many OFETs, is minimized. In fact, when the PL interlayer is integrated, both the field-effect mobility (μFET) and the on/off current amplification ratio were significantly improved. This is even more striking considering that no field-effect could be seen by spin coating a mixture of PL and OS, confirming that it is really the interface that matters in FBI-OFETs. Similar I-V curves can be measured for the PM-FBI and SA-FBI OFETs (Fig. S7 B and C, respectively), the former recorded in the double-run mode showing the occurrence of a very weak hysteresis. Typical μFET and on/off ratio are in the 10-3 cm2 V-1 s-1 and 102 ranges respectively, as reported in Table S1. It is worth mentioning that μFET and on/off ratio as high as 2 × 10-2 cm2 V-1 s-1 and 6 × 103, respectively, could be achieved with a soluble pentacene-based OFET embedding the PM. A fully functional protein integration in an OFET, also capable of good electronic performance, is obtained.

Electronic Probing of Biological Interfaces with FBI-OFETs.

The choice of the external stimuli used to probe the FBIs-OS interfaces was made considering both applicative and more fundamental aspects. For the SA FBI-OFET, the choice fell on biotin molecules due to the extremely high SA-biotin binding constant that allows, in principle, for extremely sensitive determinations. The use of (strept)avidin/biotin assay as the bench test for sensing structures is, in fact, well assessed in bioanalytical research (7, 29, 33, 34).

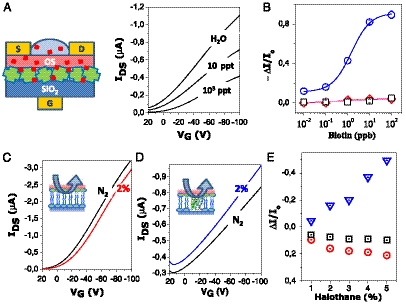

In Fig. 2A, the IDS - VG transfer characteristics of the SA-OFET exposed to deionized water and to different biotin concentrations are reported. Small molecules can easily permeate the polycrystalline P3HT reaching the underneath biolayer in a few seconds. This is proven to be the case not only for biotin but also for a larger biological molecule, such as insulin (Permeability of the P3HT film to small molecules section of SI Text and Fig. S8). In Fig. 2A, it is apparent that biotin concentration as low as 10 ppt (10 pg/mL or 41 pM) causes a drastic reduction of the current flowing in the 2D transport region. This occurrence is likely connected to the disorder induced at the protein/OS interface upon formation of the SA-biotin complex. In fact, the binding-induced disorder generates defects right at the field-induced transport critical interface, hence lowering the current. Dose curves encompassing five orders of magnitude were measured (Fig. 2B) with a reproducibility, computed as the relative standard deviation, ranging between 2% and 16% (Table S3). The SA FBI-OFET response to the lowest biotin concentration tested (10 ppt) was found to be about 9 times higher than the response to pure water. In principle, detection at even lower concentrations is possible (The SA-P3HT limit of detection section of SI Text and Table S2). The following control experiments have been designed to assess that the biotin-induced electronic response is due actually to the sole SA-biotin complex formation. Bare P3HT OFET, bovine serum albumin (a protein not able to bind biotin), as well as presaturated SA-biotin complex FBI-OFETs, were used as negative-blank controls. In fact, no response to biotin exposure was recorded in all cases (data in Fig. 2B and details of the experiment given in Fig. S9). An antibiotin monoclonal antibody (specific for biotin) FBI-OFET was used as positive control and the sensitive electronic responses reported in Fig. S10 were recorded. All these experiments prove that SA FBI-OFETs are extremely sensitive and selective devices and open the way also to the antibodies’ integration into a FBI-OFET structure. Besides, they also assess that the embedded SA retains its bioactivity. Important to outline is that the electronic probing of a small ligand, such as biotin, bound to a much larger receptor (streptavidin), is highly demanding and previously undescribed. Moreover, the assay here proposed works at a concentration level reaching state-of-the-art fluorescent assay (31) performance and challenging an extremely sensitive electrochemical determination (32). Comparison with state-of-the-art (strept)avidin electronic assay (7, 33, 34), based on biotin/(strept)avidin chemistry, evidences that at least three orders of magnitude in relative concentration have been gained with the SA FBI-OFET. More on the fundamental side, the direct electronic probing of a recognition event allows in principle to gain insights into the subtle aspects of ligand-receptor interactions.

Fig. 2.

FBI-OFET as BioElectronic Sensors. (A) SA FBI-OFET IDS - VG curves at VDS = -80 V measured in pure water and at different biotin concentrations. The device structure is sketched on the left. (B) The biotin calibration curve of the SA FBI-OFET is reported with blue circles. Data on the bare P3HT OFET (black squares) and the BSA FBI-OFET (red diamonds) are also reported. The magenta triangles are relevant to a SA-biotin saturated complex FBI-OFET. Each data point is the ΔI/Io mean value over three replicates measured on different OFET devices. Error bars, barely visible are the standard deviations (more details in Fig. S9B and Table S3). Indeed data gathered in Fig. 2B required the testing of 60 different FBI-OFETs. (C) and (D) Halothane responses of PL and PM FBI-OFETs, respectively. IDS - VG curves at VDS = -80 V measured in an inert N2 flux (black curve) and in a 2% halothane atmosphere (red or blue curve). (E) PM-OFET (blue triangles), P3HT-OFET (black squares) and PL-OFET (red circles) responses to clinically relevant halothane concentrations. The highly reversible interaction was allowed in this case to measure all the concentrations on the same device.

The response of FBI-OFETs to stimuli acting on the biological interlayer was further explored considering PL and PM FBI-OFETs’ interaction with volatile anesthetics. In the case of PLs, their interaction with anesthetic molecules has been studied since the discovery that anesthetics effectiveness correlates with their own lipophilicity (Meyer–Overton rule) (25). Hypotheses on the general anesthesia mechanism involving anesthetics interactions with PL membranes as well as with the protein hydrophobic regions have been formulated (35); among others, also PMs are known to be sensitive to anesthetics (28). The opportunity to study these key relevant interfacial interactions and possibly contribute to shed light on the general anesthesia action mechanism was the driving force to choose volatile general anesthetics as external stimuli for both the PL and PM FBI-OFETs.

The transfer characteristics of PL FBI-OFET exposed to 2% of halothane (an archetype anesthetic) have been therefore measured and are reported in Fig. 2C. Similarly to the case of the SA-biotin complex formation, also the PL FBI-OFET/halothane interaction causes a reproducible lowering of the current flowing in the channel region. Again, the disorder induced by the interaction into the otherwise extremely ordered and smooth PL bilayer, plays a key role in affecting the 2D electronic transport at the interface. Furthermore, the IDS lowering scales with the halothane concentration as shown by the dose curve (Fig. 2E) where the concentrations spanned encompass the clinical relevant range. It is remarkable that exposure of PL FBI-OFET to diethyl-ether (another archetype anesthetic) causes similar effects while other organic vapors, such as acetone, at the same saturated vapor fraction, show a much lower effect (Fig. S11). Similarly, bare P3HT-OFET shows very little response to halothane. Interestingly, drug-induced changes in the structure of PL membranes were not observed even at volatile-anesthetics concentration of 29%, this being 12 times higher than surgical concentration (36). On the basis of these evidences, a widely shared conclusion states that anesthetic molecules—at clinical concentrations—do not alter the overall structure of the lipid bilayer significantly (35, 37). The data, shown in Fig. 2 C and E, challenge this assessment and electronic detection, being particularly sensitive to subtle changes in the PL membrane at interfaces, is a useful tool to deepen the understanding of the still controversial general anesthesia action mechanism.

As already mentioned, the interactions between anesthetics and membrane proteins (ion channels and receptors) are also under scrutiny (35), and bR, being a robust archetype for membrane proteins, is among the studied systems (28), though not clinically relevant. Its absorbance spectrum and photo-reactivity are known to be influenced by anesthetics but also in this case, at concentrations higher than clinically relevant levels. Along this line, the PM FBI-OFET response to halothane has been investigated and the responses are reported in Fig. 2D. The effect of the halothane interaction with the PM is opposite to that of the PL one: A current increase can be seen and the dose curve (Fig. 2E) is steeper. The PM FBI-OFET behavior opposite to the PL one is readily explained, recalling that halothane generates pKa changes in the bR (28) eventually provoking a protons release and H+ are finally injected into the p-type channel by the gate field. Therefore, the final effect of proton injection into the OFET device is similar for yellow light illumination and halothane exposure. The interfacial nature of the phenomenon is further supported by the independence of the phenomenon from the PM layer thickness.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have proposed a unique way to integrate fully into OFETs different classes of biological structures, retaining their functionality. The integration of soft matter and solid-state organic electronics leads to a high-performing transistor whose response reflects the functionality of the biological interlayer under specific stimuli. Accordingly, the FBI-OFETs perform as extremely sensitive label-free electronic sensors detecting down to few parts per trillion concentrations, challenging well-assessed label-needing optical methods. More importantly, the direct coupling between the probing electronic channel and a biointerface can open the way to so far inaccessible pieces of information that can foster previously undescribed developments. As a proof-of-principle, the authors have shown how FBI-OFETs could be a useful tool in the study of the still-controversial general anesthesia action mechanism. Along the same line, the direct probe of the SA-P3HT interface allows the study of the biotin-streptavidin complex formation at extremely low biotin concentration, possibly giving access to information such as, for instance, the kinetics of the process. Besides, the platform device fabrication is not technologically highly demanding, this—in principle—being a further element possibly fostering its diffusion in multidisciplinary investigations.

Materials and Methods

Fabrication of FBI-OFETs.

The FBI-OFETs have been fabricated starting from a highly n-doped silicon substrate. The gate dielectric is thermally grown SiO2, 100, or 300 nm thick. The SiO2 surface was cleaned through a rinsing procedure involving treatment with solvents of increasing polarity. The FBI layers have been subsequently deposited, directly on the SiO2, by very slow speed spin coating. Specifically, the following procedures were implemented:

Phospholipid (PL) Bilayers.

50 μL of an aqueous suspension (5 mg/mL) of single unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) of phosphatidylcholine PLs were deposited on the cleaned SiO2 surface, by spin coating at 200 rpm for 20 min.

Purple membrane (PM):

lyophilized PMs were first suspended in distilled water by mild sonication on ice then diluted with water to a final PM concentration of 10 μg/mL and 60 μL of this PM suspension was spin coated at 150 rpm for 90 min directly on the cleaned SiO2 surface (or on glass support in the case of optical measurements).

Streptavidin (SA):

A 10 μg/mL aqueous solution of SA was spin coated at 200 rpm for 40 min directly on the cleaned SiO2 surface.

The organic semiconductor (OS) was deposited afterward directly over the FBI layers. Specifically, the poly(3-hexylthiophene-2,5-diyl)—P3HT—(BASF, Sepiolid™ P200, regioregularity > 98%) was purified as detailed in SI Text. The purified product was dissolved in chloroform (2.6 mg/mL) and the deposition of the OS was performed by spin coating at a spin rate of 2,000 rpm for 30 s. Source (S), drain (D) and gate (G) contacts were deposited by thermal evaporation (8 × 10-7 torr) of gold through a shadow mask. The geometry used to define the S and D contacts results in a sequence of several rectangular pads (4 mm wide) spaced by 200 μm. The OFET channel length is L = 200 μm while the channel width is W = 4 mm.

Electronic Response Measurements.

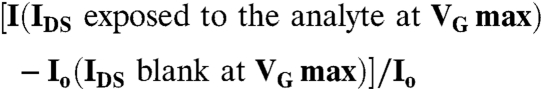

The OFETs have been operated in the common-source configuration and critical electronic performance parameters (μFET, on/off ratio and VT) were extracted from the current-voltage characteristics using assessed procedures (17). The electronic responses have been evaluated by measuring the OFET IDS - VG transfer-characteristics, by sweeping the gate bias and measuring the current flowing in the OFET channel while keeping VDS fixed at -80 V. The transfer characteristics were first measured in N2 or deionized H2O environment (blank) and then in the presence of the different analyte concentrations. The measurements were performed in the dark and the response time was within 45 s, namely the transfer characteristic sweep time. Both the bare OS OFET devices as well as the OFET integrating the FBI layers were then exposed to the species to be tested. The transfer characteristics normalized source drain current changes (ΔI/Io) are given by:

|

To perform the sensing experiments, different procedures were used for the detection of volatile and liquid substances.

Procedure 1: Determination of halothane and volatile organic vapors.

Io was evaluated by measuring the transfer characteristics of the bare P3HT OFET sensor in a N2 flux. Afterward, on the same transistor, a controlled concentration flow of the analyte was delivered, and the current was measured. A single-dose curve was taken from the same device as the interaction was fully reversible with the volatile analytes chosen.

Procedure 2: Determination of biotin in water.

A droplet (2 μL) of deionized water was deposited directly on the SA-P3HT surface between two contiguous source and drain pads and dried under a nitrogen flow. The transfer characteristics were then measured, and the Io current value was taken. The solution containing the biotin analyte, at a randomly chosen concentration, was then deposited on the same transistor and incubated for 15 min. Subsequently, the not-bound excess analyte was removed by washing with a 2 μL droplet of deionized water for three times. The device was then dried under a nitrogen flow. As the involved interactions are irreversible in this case, each data point was taken from a different transistor. Therefore, for each given concentration, three I-values were measured and the mean ΔI/Io was plotted on the calibration curve along with the associated standard deviation (relevant data in Table S3). Overall, 15 different OFETs were tested for each curve.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Prof. A. Dodabalapur, Dr. M. Ambrico, and Prof. T. Ligonzo are acknowledged for useful discussions. Dr. F. Ridi is acknowledged for producing the AFM images. This work has been partially supported by the following projects: SEED—“X-ray synchrotron class rotating anode microsource for the structural micro imaging of nanomaterials and engineered biotissues (XMI-LAB)”- IIT Protocol n.21537 of 23/12/2009; FlexSMELL—“Gas Sensors on Flexible Substrates for Wireless Applications”—Marie Curie ITN FP7-PEOPLE-ITN-2008-238454; and BioEGOFET- “Electrolyte-Gated Organic Field-Effect BIOsensors”- FP7-ICT-2009.3.3-248728. E.F. and P.B. acknowledge partial support from the Consorzio Interuniversitario per lo sviluppo dei Sistemi a Grande Interfase CSGI-Firenze. G.P. acknowledges partial support from MIUR of Italy (Grant PRIN/2008 prot. 2008ZWHZJT).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1200549109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jin Y, et al. Bacteriorhodopsin as an electronic conduction medium for biomolecular electronics. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:2422–2432. doi: 10.1039/b806298f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patolsky F, et al. Electrical detection of single viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14017–14022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406159101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owens RM, Malliaras GG. Organic electronics at the interface with biology. MRS Bull. 2010;35:449–456. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian B, et al. Three-dimensional, flexible nanoscale field-effect transistors as localized bioprobes. Science. 2010;329:830–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1192033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misra N, et al. Bioelectronic silicon nanowire devices using functional membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13780–13784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904850106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern E, et al. Label-free immunodetection with CMOS-compatible semiconducting nanowires. Nature. 2007;455:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature05498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X, Moran-Mirabal JM, Craighead HG, McEuen PL. Supported lipid bilayer/carbon nanotube hybrids. Nature Nanotec. 2007;2:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon Y, et al. Polypyrrole nanotubes conjugated with human olfactory receptors: high-performance transducers for FET-type bioelectronic noses. Angewandte Chemie Int Ed. 2009;48:2755–2758. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKinley BA. ISFET and fiber optic sensor technologies: In vivo experience for critical care monitoring. Chem Rev. 2008;108:826–844. doi: 10.1021/cr068120y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodabalapur A, Torsi L, Katz HE. Organic transistors: Two-dimensional transport and improved electrical characteristics. Science. 1995;268:270–271. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5208.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokolov AN, Roberts ME, Bao Z. Fabrication of low-cost electronic biosensors. Materials Today. 2009;12:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irina-Vladu M, et al. Exotic materials for bio-organic electronics. J Mat Chem. 2011;21:1350. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon DT, et al. Organic electronics for precise delivery of neurotransmitters to modulate mammalian sensory function. Nat Mater. 2009;8:742–746. doi: 10.1038/nmat2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yumusak C, Singh Th.B, Sariciftci NS, Grote JG. Bio-organic field effect transistor based on crosslinked deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) gate dielectric. Appl Phy Letters. 2010;95:263304–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D-H, Viventi J. Dissolvable films of silk fibroin for ultrathin conformable bio-integrated electronics. Nat Mater. 2010;9:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nmat2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dezieck A, et al. Threshold voltage control in organic thin film transistors with dielectric layer modified by genetically engineered polypeptide. Appl Phys Letters. 2010;97:13307–13309. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torsi L, Dodabalapur A. Organic thin-film transistors as plastic analytical sensors. Anal Chem. 2005;77:380A–387A. doi: 10.1021/ac053475n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torsi L, et al. A sensitivity-enhanced field-effect chiral sensor. Nat Mater. 2008;7:412–417. doi: 10.1038/nmat2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Someya T, Dodabalapur A, Gelperin A, Katz HE, Bao Z. Integration and response of organic electronics with aqueous microfluidics. Langmuir. 2002;8:5299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts ME, et al. Water-stable organic transistors and their application in chemical and biological sensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12134–12139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802105105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicoira F, et al. Influence of device geometry on sensor characteristics of planar organic electrochemical transistors. Adv Mater. 2010;22:1012–1016. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder R, Majewski LA, Grell M. High-performance organic transistors using solution-processed nanoparticle-filled high-k polymer gate insulators. Adv Mater. 2005;17:1535–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 23.See KC, Becknell A, Miragliotta J, Katz HE. Enhanced response of n-channel naphthalenetetracarboxylic diimide transistors to dimethyl methylphosphonate using phenolic receptors. Adv Materials. 2007;19:3322–3327. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan HU, et al. In situ, label free DNA detection using organic transistor sensors. Adv Mater. 2010;22:4452–4456. doi: 10.1002/adma.201000790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Missner A, Pohl P. 110 years of the Meyer-Overton Rule: Predicting membrane permeability to gasses and other small compounds. Chem Phys Chem. 2009;10:1405–1414. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seen Y, et al. Stabilization of the membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin to 140 °C in two dimensional films. Nature. 1993;366:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Povilas-Kietis B, Saudargas P, Varo G, Valkumas L. External electrical control of the proton pumping in bacteriorhodopsin. Eur Biophys J. 2007;36:199–221. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura S, et al. Volatile anesthetics cause conformational changes of bacteriorhodopsin in purple membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;818:421–424. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez M, et al. Interaction of Biotin with Streptavidin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11288–11294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koyama K, Yamaguchi N, Miyasaka T. Antibody-mediated bacteriorhodopsin orientation for molecular device architectures. Science. 1994;265:762–765. doi: 10.1126/science.265.5173.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Son X, Swanson BI. Rapid assay for avidin and biotin based on fluorescent quenching. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;442:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kizek R, et al. An analysis of avidin, biotin and their interaction at attomole levels by voltammetric and chromatographic techniques. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;381:1167–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-3027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui Y, Wei Q, Park H, Lieber CM. Nanowire nanosensors for highly sensitive and selective detection of biological and chemical species. Science. 2001;293:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1062711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Star A, Gabriel JCP, Bradley K, Grüner G. Electronic detection of specific protein binding using nanotube FET devices. Nano Letters. 2003;3:459–463. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vemparala S, Domene C, Klein ML. Computational studies on the interaction of inhalation anesthetics and proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:103–110. doi: 10.1021/ar900149j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Where do general anaesthetics act? Nature. 1978;273:339–342. doi: 10.1038/274339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anaesthesia. Nature. 1994;367:607–614. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.