Background: PrPSc is believed to have a β-sheet-rich structure.

Results: Established human IgG1 stained β-form PrP in prion-infected cells but had no inhibitory activity against the propagation of PrPres.

Conclusion: β-Sheet-rich PrP was generated and accumulated in cells.

Significance: β-Form PrP aggregates play roles in cytotoxicity, whereas prion or PrPSc is responsible for prion propagation.

Keywords: Antibody Engineering, Confocal Microscopy, Immunohistochemistry, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Prions, PrP-specific Antibody, β-Conformation

Abstract

We prepared β-sheet-rich recombinant full-length prion protein (β-form PrP) (Jackson, G. S., Hosszu, L. L., Power, A., Hill, A. F., Kenney, J., Saibil, H., Craven, C. J., Waltho, J. P., Clarke, A. R., and Collinge, J. (1999) Science 283, 1935–1937). Using this β-form PrP and a human single chain Fv-displaying phage library, we have established a human IgG1 antibody specific to β-form but not α-form PrP, PRB7 IgG. When prion-infected ScN2a cells were cultured with PRB7 IgG, they generated and accumulated PRB7-binding granules in the cytoplasm with time, consequently becoming apoptotic cells bearing very large PRB7-bound aggregates. The SAF32 antibody recognizing the N-terminal octarepeat region of full-length PrP stained distinct granules in these cells as determined by confocal laser microscopy observation. When the accumulation of proteinase K-resistant PrP was examined in prion-infected ScN2a cells cultured in the presence of PRB7 IgG or SAF32, it was strongly inhibited by SAF32 but not at all by PRB7 IgG. Thus, we demonstrated direct evidence of the generation and accumulation of β-sheet-rich PrP in ScN2a cells de novo. These results suggest first that PRB7-bound PrP is not responsible for the accumulation of β-form PrP aggregates, which are rather an end product resulting in the triggering of apoptotic cell death, and second that SAF32-bound PrP lacking the PRB7-recognizing β-form may represent so-called PrPSc with prion propagation activity. PRB7 is the first human antibody specific to β-form PrP and has become a powerful tool for the characterization of the biochemical nature of prion and its pathology.

Introduction

Prion diseases are fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative disorders that include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle. It has been proposed that a misfolded form of prion protein is responsible for the infectivity of prion disease, and the pathogenesis of prion disease involves a conformational change of prion protein (PrP)2 from PrPC to PrPSc (1). PrPC is a monomeric isoform, rich in α-helical structure, and sensitive to digestion by proteinase K (PK). In contrast, multimers are PrPSc characterized as PrPres by enhanced resistance toward PK digestion. Consequently, it is believed first that PrPSc might have a β-pleated sheet structure because all amyloids studied have been found to have this structure and second that this β-sheet-rich PrPSc binds specifically to PrPC, propagating its altered conformation via a templating mechanism, which is a prion activity. In other words, it was demonstrated that PrPSc, defined as PrP27–30, was generated and accumulated in prion-infected cells or brain. However, there is no direct evidence of whether prion or PrPSc has a β-sheet-rich structure, although there is suggestive evidence of FTIR using centrifugation-purified aggregates of prion-infected brain extracts (2, 3).

Antibodies to these proteins are powerful tools to clarify these questions. However, 1) the purification procedure of PrPSc was based on the centrifugation precipitation of molecular aggregates using PEG or sodium phosphotungstic acid, which does not necessarily guarantee the specificity to a prion (2, 4–7). 2) The specificity of an anti-PrPSc antibody was defined by the existence of PrP27–30 resulting from PK-treated prion-infected brain or cell extracts that are immunoprecipitated with tested antibodies. These experiments showed that PrP27–30 was resolved from PK-resistant PrP but do not directly indicate that PrP27–30 is generated from β-sheet-rich PrP; i.e. they rather suggest a generation of β-sheet-rich PrP by experimental procedures including the use of PK, denaturing agents, or detergents (8). 3) All antibodies established so far are either anti-PrPSc/PrPC or anti-PrPC antibodies (9). More recently, mouse monoclonal IgG W261, which reacts exclusively with PrPSc but not PrPC, has been reported by cell fusion technology using spleen cells immunized with sodium phosphotungstic acid-precipitated PrPSc derived from prion-infected brain extracts (10). This study did not address the question of whether PrPSc was the β-form PrP or not.

In this study, using the conformation-defined recombinant PrPs and a human single chain Fv-displaying phage library, we have established two human IgG, PRB7 and PRB30, which are specific to the β-form but not the α-form of recombinant PrP of human, bovine, sheep, and mouse. Epitope mapping analysis showed that PRB7 IgG recognized residues 128–132 of the full-length prion protein.

When prion-infected ScN2a cells were cultured in the presence of PRB7, apoptotic cells with numerous PRB7 binding signals including large aggregates were gradually generated during 4 days of culture. This finding is the first direct evidence of the generation and accumulation of β-sheet-rich prion protein in ScN2a cells. Interestingly, in these apoptotic cells, SAF32-staining granules were distinct from PRB7-binding aggregates, suggesting that SAF32-binding PrP does not have a PRB7-recognizing β-sheet structure, whereas PRB7-binding PrP may not have the N-terminal octarepeat region of PrP. After ScN2a cells were cultured in the presence of PRB7 or SAF32 for 3 days, PK-treated cell lysate was immunoblotted by 6D11 to examine the inhibitory effects of PRB7 IgG on the generation/accumulation of PrPSc. Surprisingly, PRB7 IgG had no influence, whereas SAF32 strongly inhibited the generation/accumulation of PrPres.

Thus, this study reports the first establishment of a human IgG antibody recognizing β-form PrP but not α-form PrP and the use of this antibody to provide direct evidence of the de novo generation and conversion of β-sheet-rich PrP in prion-infected cells. PRB7 IgG can be a powerful tool to purify the β-form PrP generated de novo and demonstrate its biochemical basis and significance to elucidate structural evidence of prion infectivity and neurotoxicity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

The pQE30 vector and Escherichia coli (M15) were obtained from Qiagen. The 6D11 antibody was purchased from Signet. A silver stain II kit was from Wako. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and anti-β-tubulin (I) antibody were purchased from Sigma. Recombinant anti-PrP Fab HuM-P, HuM-D18, HuM-D13, HuM-R72, and HuM-R1 were purchased from Inpro Biotechnology. GAHu/Fab/Bio was purchased from Nordic Immunology Inc. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-goat mouse IgG, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, and goat anti-human IgG Fc-HRP were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. HisTrapTM HP, the anti-His tag antibody, and HiTrapTM Protein A HP were from GE Healthcare. The mouse anti-E tag monoclonal antibody, HRP-conjugated anti-E tag mAb, the anti-E tag antibody-Sepharose column, and the anti-M13 monoclonal antibody were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. The 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine solution was from Calbiochem. SAF32 was purchased from SPI Bio (Ann Arbor, MI). Control human IgG/κ was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin and HRP-conjugated streptavidin were purchased from Vector Laboratories. The Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction kit was from Applied Biosystems. NheI, BstApI, ApaI, BsaWI, BbsI, and HindIII were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). T4 DNA ligase was obtained from Takara Bio Inc. Opti-MEM, the SuperScriptTM First-Strand Synthesis System, pcDNA3.1TM(−) mycHisA, pcDNA3.1(−) Zeo, the FreeStyleTM MAX reagent, Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 568, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-human IgG, Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-mouse IgG, and Alexa Fluor 488-succinimidyl ester were obtained from Invitrogen. Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Abcam. The labeling of antibody with Alexa Fluor 488 was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. DAPI was purchased from Cambrex Bio Science.

Expression Vector

PrP expression vectors were constructed as described (11). Briefly, DNA fragments corresponding to human PrP residues 23–231 were independently amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using forward primer (5′-gcggatccaagaagcgcccgaagcctgga-3′) and back primer (5′-ccaagcttctatcagctcgatcctctctggtaata-3′) from genomic DNA of HEK293T cells. The fragments were digested with BamHI and HindIII and inserted into a pQE30 vector bearing the His tag sequence. Bovine PrP(25–242), mouse PrP(23–231), or sheep PrP(25–234) expression vectors were constructed in a similar way.

Protein Expression and Purification

Constructed histidine-tagged recombinant full-length prion protein (rPrP; amino acids 23–231) was expressed in E. coli (M15) and purified by HisTrap HP as described (8). Briefly, fractions containing human rPrP were diluted to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml using a 0.1 m Tris buffer (pH 8.0) containing 9 m urea and 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The dialyzed solution was diluted 3-fold with 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid in water, loaded on a 10 × 150-mm WP300 C4 HPLC column (GL Sciences, Tokyo, Japan), and eluted using a gradient of 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile. Fractions containing oxidized PrP were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C as described (8).

Refolding

Refolding of rPrP was performed according to the methods of Jackson et al. (12). Briefly, to prepare α-form PrP, a stock solution of rPrP (1 mg/ml in 6 m GdnHCl) was dialyzed into a 10 mm sodium acetate, 10 mm Tris acetate buffer (pH 8.0). In the case of β-form PrP, rPrP was dissolved in a 100 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 6 m GdnHCl, 10 mm Tris acetate (pH 8.0) buffer for 16 h and then dialyzed with a 10 mm sodium acetate, 1 mm DTT (pH 4.0) buffer. A half-volume of the dialysis buffer was replaced with fresh buffer, and this procedure was repeated every 12 h for a total of 10 times. Refolded proteins were stored at 4 °C. The PrP concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer, Ultrospec 2000 (Amersham Biosciences), using a molar extinction coefficient E280 of 56,650 m−1 cm−1.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded in a 0.1-cm cuvette with a J-820 spectrometer (Jasco) scanning at 20 nm/min with a bandwidth of 1 nm and data spacing of 0.5 nm. Each spectrum represents the average of five individual scans after subtracting the background spectra (8).

Atomic Force Microscopy

Atomic force microscopy images were recorded on an SPI-3800 (Seiko Instruments, Chiba, Japan) immediately after dilution of the 5.4 mg/ml solution of the β-form PrP and displaying on a fresh mica surface.

PK Digestion

Recombinant PrP (100 μg/ml) was treated with the indicated concentration of PK for 1 h at 37 °C. ScN2a cell lysates were treated with PK (final concentration, 20 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C, then PMSF at a final concentration of 2 mm was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 45 min at 4 °C. The pellet was dissolved in a 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 10 min for immunoblotting analysis.

Immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE was performed as described (13, 14). Purified PRB7 IgG was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with the silver stain II kit.

Immunoblotting was performed as described (13, 15). Briefly, samples were added to a 2× sample buffer, boiled for 10 min, separated on a 16.5% Tricine-polyacrylamide gel, and electrotransferred onto a PVDF membrane at 150 V for 90 min using a semidry electroblotter (Sartorius, Tokyo, Japan). The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS overnight. Specific binding of the antibody to proteins was determined by incubating the membrane for at least 1 h with the 6D11 antibody (1:4000). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG served as a secondary antibody (1:5000). Protein signals were visualized using ECL on a LAS-1000 image analyzer (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan). The Tricine gel was stained with the silver stain II kit.

Phage Libraries

The human single chain Fv (scFv)-displaying M13 phage library constructed using the pCANTAB 5E (4.5-kb) phagemid vector was used in this study as described (13, 15). The peptide-displaying phage libraries (Ph.D.-12) were purchased from New England Biolabs. The Ph.D.-12 library contains linear peptides composed of 12 random amino acids.

Biopanning

Biopanning was performed as described (13–15). To isolate the antibody phage specific to β-form PrP, the scFv phage library (1 × 1012 pfu/50 μl) was preabsorbed with α-form PrP (5 μg) coating an immunotube under the conditions of a folding buffer (pH 8.0). One hour later, unbound phages were collected and added to a β-form PrP (5 μg)-coated immunotube under the conditions of a folding buffer (pH 4.0). After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, the unbound phages were discarded by washing the immunotubes seven times with folding buffer (pH 4) containing 0.1% Tween 20. The bound phages were then eluted with 0.1 m glycine-HCl (pH 2.2), immediately neutralized with 1 m Tris-HCl (pH 9.1), and amplified by infection with log phase E. coli strain TG1 cells. The phages and soluble scFv were prepared as described (13–15). To isolate peptide phage to PRB7 IgG, unrelated control human IgG/κ and PRB7 IgG were separately immobilized on polystyrene 96-well microplates (300 ng/50 μl/well). The Ph.D.-12 phage library (4 × 1011 transforming units) was preabsorbed on a plate immobilized by unrelated control human IgG/κ. The phages were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with immobilized PRB7 IgG, and the binding phages were eluted with 0.1 m glycine-HCl (pH 2.2). The eluate was immediately neutralized with 1.0 m Tris-HCl (pH 9.1) and amplified by infecting ER2738.

Preparation of Aβ42 Conformers

Aβ42 conformers were prepared as described (14, 16). Synthetic Aβ42 peptides (purity 90–95% by mass spectrum; Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan) were solubilized in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (Wako, Tokyo, Japan) at a concentration of 1 mg/ml (222 μm) and separated into aliquots in microcentrifuge tubes. Immediately prior to use, the 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol-treated Aβ42 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Wako) to 4 mg/ml (888 μm) and diluted with a 20 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to a concentration of 40 μm.

ELISA

ELISA was performed as described (13–15). Briefly, a microtiter plate (Nunc, Denmark) was coated with refolded PrP (100 ng/50 μl/well) and anti-His tag mAb (80 ng/40 μl/well) for 1 h at room temperature. BSA (0.25%)/PBS was used as blocking buffer. BSA (0.25%)/PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 was used as washing buffer. Anti-PrP Fab (HuM-P, HuM-D18, HuM-D13, HuM-R72, or HuM-R1; 1:500) (17–19) was detected by the biotinylated anti-Fab antibody (1:1000; 50 μl/well) in combination with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin. Soluble PRB7 scFv (200 ng/40 μl/well) was detected by the anti-E tag antibody in combination with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000). PRB7 IgG (0–1 μg/ml; 50 μl/well) was detected by goat anti-human Fc-HRP (1:2000; 50 μl/well). SAF32 (0.1 μg/ml; 50 μl/well) was detected by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; 50 μl/well). Antibody phage clones (5 × 1011 transforming units/40 μl) were incubated with the indicated refolded PrP (200 ng/40 μl) in a folding buffer (pH 4.0 or 8.0) and then captured on wells coated with an anti-His tag mAb. The bound phage was detected using a biotinylated anti-M13 mAb (1:1000) followed by the addition of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1:1000). In the case of sandwich ELISA, PRB7 or control human IgG/κ (100 ng/25 μl) was incubated with human β-form PrP (100 ng/25 μl) in a pH 4.0 folding buffer for 1 h and then added into wells precoated with an anti-PrP mAb, SAF32 or 6D11 (100 ng/50 μl). After treatment with a blocking and washing solution, the bound antibody was detected using an HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG (1:5000). In the case of the alkaline phosphatase development system, absorbance was measured at 405 nm during incubation with 50 μl of a p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 10% diethanolamine solution by use of a microplate reader (NJ-2300, PerkinElmer, Tokyo). In the case of the HRP development system, the plates were incubated with 50 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine solution for 3 min at room temperature in the dark. After addition of 50 μl of 1 n HCl, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using the EnSpire 2300 Multilabel Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

To perform the epitope mapping of PRB7 IgG, a microtiter plate was coated with 50 ng/50 μl/well PRB7 IgG or control IgG/κ for 1 h at 4 °C. After blocking the plates with 0.25% BSA, PBS, Ph.D.-12 phage clones (50 μl/well of 1 × 1011 virions/ml) were added to each well followed by incubation with a biotinylated anti-M13 monoclonal antibody (1:2000) in combination with HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1:2000).

DNA Sequencing

The nucleotide sequences of the scFv genes were identified using the Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction kit with primers pCANTAB5-S1 (5′-CAACGTGAAAAAATTATTATTCGC-3′) and pCANTAB5-S6 (5′-GTAAATGAATTTTCTGTATGAGG-3′).

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

SEC (7.8 × 300-mm TSK-GEL G3000SWXL HPLC column, Tosoh Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was performed as described (20). The column was equilibrated with buffer A (20 mm sodium acetate (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl, 1 m urea, 0.02% sodium azide) for α-form PrP or buffer B (20 mm sodium acetate (pH 4.0), 200 mm NaCl, 1 m urea, 0.02% sodium azide) for β-form PrP and used at room temperature with a flow rate of 1 ml/min (20).

Construction of PRB7 IgG Expression Vectors

DNA primers were synthesized by Hokkaido System Science Co. (Sapporo, Japan). The outline is presented in supplemental Figs. S1 and S2. The heavy-chain leader sequence (Vhls; HAVT20) (21), heavy-chain variable gene (Vh), light-chain leader sequence (Vlls) (13), and light-chain variable gene (Vl) of PRB7 were amplified by PCR (22) using Vhls forward primer 1 (5′-AAAAATCTAGAGCTAGCGATGGCATGCCCTGGCTTCCTGTGGGCACTTGTGATCTCC-3′), Vhls back primer (5′-AAAAAGCAACAGCTGCACCTCAGCCATGGAAAATTCAAGACAGGTGGAGATCACAAGTGCC-3′), Vh forward primer (5′-GAGGTGCAGCTGTTGCAG-3′), Vh back primer (5′-AAAAAGGGCCCTTGGTGGATGAGGAGACGGTGAC-3′), Vlls forward primer (5′-AAAAAGCTAGCGATGGAAACCCCAGCGCAGCTTCTCTTCC-3′), Vlls back primer (5′-AAAAATCCGGTGGTTGGGAGCCAGAGTAGCAGGAGGAAGAGAAGCTGCGC-3′), Vl forward primer (5′-AAAAAACCGGAGACATCGTGATGACCCAG-3′), and Vl back primer (5′-AAAAAGAAGACAGATGGTGCAGCCACAGTACGTTTAATCTCCAGTCGGT-3′). The Vhls fragment contains the NheI site at the 5′ terminus and the BstApI site at the 3′-terminus. The Vh fragment contains the BstApI site at the 5′ terminus and the ApaI site at the 3′ terminus. The Vlls fragment contains the NheI site at the 5′ terminus and the BsaWI site at the 3′ terminus. The Vl fragment contains the BasWI site at the 5′ terminus and the BbsI site at the 3′ terminus. The constant region of human immunoglobulin heavy chain 1 (IGHC1) and human immunoglobulin κ-chain (IGKC) (21) was amplified from cDNA of peripheral blood lymphocytes by PCR using IGHC1 forward primer (5′-TCCACCAAGGGCCC-3′), IGHC1 back primer (5′-AAGCTTCGGAGACAGGGAGAG-3′), IGKC forward primer (5′-ACTGTGGCTGCACCATC-3′), and IGKC back primer (5′-AAGCTTCTAACACTCTCCCCTGTTG-3′). The IGHC1 fragment contains the ApaI site at the 5′ terminus and the HindIII site at the 3′ terminus. The IGKC fragment contains the BbsI site at the 5′ terminus and the HindIII site at the 3′ terminus. The cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System.

For the construction of the PRB7 IGHC1 expression vector, the Vhls fragment and the Vh fragment were digested with BstApI. These two fragments were ligated with T4 DNA ligase. The ligated sample was amplified by PCR using Vhls forward primer 2 (5′-AAAAATCTAGAGCTAGCGATGGCATG-3′) and the Vh back primer. This amplified fragment and the IGHC1 fragment were digested with ApaI, ligated, and amplified by PCR using Vhls forward primer 2 and the IGHC1 back primer. This amplified fragment was digested with NheI and HindIII and inserted into a pcDNA3.1(−) mycHisA vector.

For the construction of the PRB7 IGHC1 expression vector, the Vlls fragment and the Vl fragment were digested with BsaWI, ligated with T4 DNA ligase, and amplified by PCR using the Vlls forward primer and the Vl back primer. This amplified fragment and the IGKC fragment were digested with BbsI, ligated, and amplified by PCR using the Vlls forward primer and the IGKC back primer. The amplified fragment was digested with NheI and HindIII and inserted into a pcDNA3.1(−) Zeo vector.

Protein Expression and Purification of PRB7 IgG

FreeStyle 293F cells (Invitrogen; 1 × 106 cells/ml) were co-transfected with an equimolar mixture (final total DNA concentration, 1 μg/ml) of a heavy-chain expression vector and a light-chain expression vector with the FreeStyle MAX reagent (final concentration, 1 μl/ml) according to the manufacturer's instructions (23). Transfections were performed in 500-μl cultures as described above. One week later, the supernatant was harvested from the culture by centrifugation. PRB7 IgG was purified using HiTrap Protein A HP according to the manufacturer's instructions (13).

Computer Simulation of PrPs

The computer simulation was performed on the basis of the NMR structure of the human PrP (amino acids 124–227; Protein Data Bank code 1QM0) (24) using PyMOL software. Human IgG was simulated by use of Molecular Operating EnvironmentTM (MOE, Version 2009.10) (supplemental Fig. S3).

Cell culture

ScN2a cells, N2a58 cells overexpressing mouse PrP (a genotype with codons 108L and 189T), FF32 cells, or N2aL1 cells were used. FF32 cells were cloned from F3 cells (an N2a58 cell line infected with a prion Fukuoka-1 strain derived from mouse brain infected with a brain of a Gerstmann-Straüssler-Scheinker syndrome patient) or N2aL1 cells (an N2a58 cell line infected with the 22L strain derived from mouse brain infected with scrapie) as described previously (25, 26). All cells were cultured in Opti-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cells (5 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate) were cultured in the absence or presence of varying concentrations of PRB7 IgG, SAF32, control human IgG/κ antibodies (azide-free), Alexa Fluor 488-PRB7 IgG, or Alexa Fluor 488-control human IgG/κ antibodies (azide-free) at 37 °C on 24-well microplates (Iwaki Glass Co.) (27).

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed as described (28–30). Briefly, cells were cultured in an Advanced TCTM glass bottom cell culture dish (Greiner Bio-One, Germany). Three days later, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and then washed with PBS. In the case of staining of β-actin or β-tubulin, cells were fixed with cold methanol for 30 min at −20 °C. Fixed cells were permeated with 0.2% saponin, PBS for 20 min; washed with PBS; and blocked with 3% BSA, PBS for 30 min at room temperature. These cells were incubated with SAF32 (5 μg/ml) for 1 h at room temperature in 1.5% BSA, 0.1% saponin, PBS. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with DAPI (1:2000), Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-human IgG (1:2000), and Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-mouse IgG (1:2000) diluted in 1.5% BSA, 0.1% saponin, PBS for 1 h at room temperature. For Annexin V staining, non-fixed cells were incubated with Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 568 (1:100) diluted in an annexin binding buffer (10 mm HEPES, 140 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4) for 30 min at room temperature. To stain the denatured prion, permeated cells were treated with 6 m GdnHCl for 10–30 min at room temperature.

Confocal Microscopy Analysis

Fluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal laser microscope (Carl Zeiss, Tokyo, Japan). Orthogonal projections were generated from z-stacks, and profile projections were generated using Zeiss LSM software (Carl Zeiss).

RESULTS

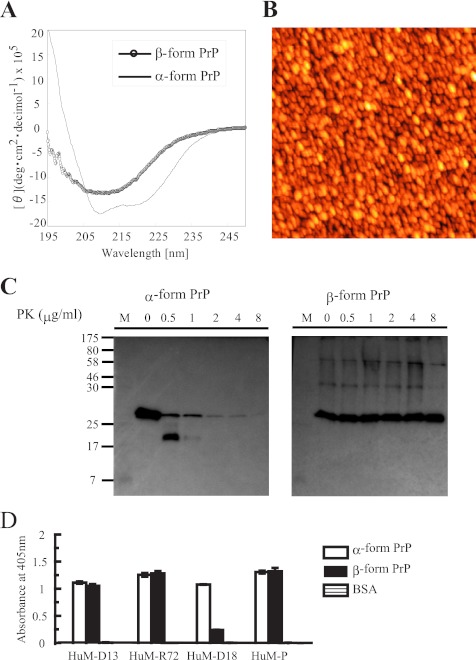

Characterization of Recombinant Human Full-length PrP

PrP was prepared using recombinant prion protein as described (8). CD analysis showed the typical characteristics of the α-form of PrP with a structure rich in α-helical content and of the β-form with a β-sheet rich structure, respectively (Fig. 1A) (31). Atomic force microscopy of the β-form of PrP displayed a round shaped particle, showing the formation of globular structures with an apparent diameter (horizontal) of ∼47 nm and an apparent height of ∼1.6 nm (Fig. 1B). α-Form PrP was digested completely with 2 μg/ml PK, whereas β-form PrP showed resistant fragments at 8 μg/ml PK treatment (Fig. 1C). D18 antibody recognizes the epitope 133–157 of α-form PrP but not β-form PrP (17–19). In accordance with this finding, D18 did not bind to this β-form PrP. D13 (epitope 96–106 of PrP), R72 (epitope 152–163 of PrP), or the P antibody (epitope 96–105 of PrP) did not distinguish the structural difference between the α-form and the β-form of PrP (Fig. 1D) (17–19).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of human full-length prion protein refolded in vitro. Refolding was performed according to the protocol of Jackson et al. (12). A, CD spectra for the protein refolded at pH 8.0 (line; α-form PrP) and the protein refolded at pH 4.0 (open circle; β-form PrP). A double minimum at 222 and 208 nm or a minimum at ∼215 nm is characteristic of an α-helical structure or β-sheet structure, respectively (26). B, atomic force microscopy image of β-form PrP. C, limited PK digestion of β-form PrP. α-Form PrP or β-form PrP (1 μg) was incubated with varying concentrations (0–8 μg/ml) of PK for 30 min at 37 °C. PrP was detected by immunoblot analysis with the 6D11 antibody. D, reactivity of α-form PrP or β-form PrP with HuM anti-PrP antibodies (17–19). Region 133–157 recognized by the anti-PrP Fab antibody (D18) is cryptic in β-PrP. Data represent the mean values ±S.D. deg, degrees.

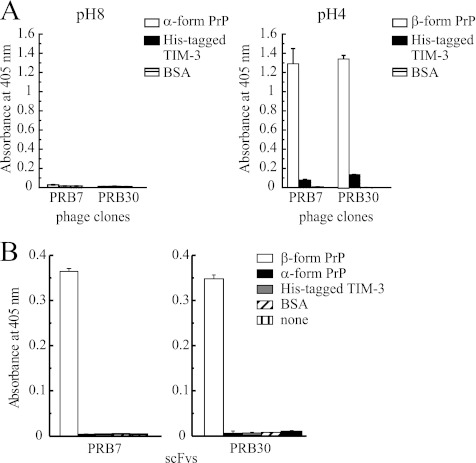

Biopanning against β-Form of PrP

The immunotube for biopanning was prepared by coating the tube with β-form PrP (5 μg) dissolved in pH 4.0 solution. The phage solution (1012 pfu/50 μl) preabsorbed to α-form PrP was added to the β-form PrP-coated immunotube under the condition of a folding buffer (pH 4.0). After two rounds of biopanning selection, ELISA was performed under the pH 8.0 condition to determine the binding activity to α-form PrP because α-form PrP was folded under the pH 8.0 condition. On the other hand, the binding activity to β-form PrP was examined under the pH 4.0 condition. A total of 384 clones were isolated and tested for binding activity to antigen by ELISA. Two scFv phage clones, designated as PRB7 and PRB30, were selected to be specific for the β-form of PrP without binding activity to the α-form of PrP (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Binding specificity of β-form PrP-selected scFv phage clones by ELISA. A, phage clones (PRB7 or PRB30; 5 × 1011 transforming units/40 μl) were incubated with the indicated antigens (200 ng/40 μl) in a pH 8.0 or 4.0 folding buffer for 1 h and then added to wells coated with an anti-His tag mAb. The bound phage was detected using a biotinylated anti-M13 monoclonal antibody (1:1000) followed by the addition of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1:1000) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” His-tagged TIM-3 or BSA was used as a control protein. B, soluble PRB7 or PRB30 scFv antibody (1 μg/200 μl) was added to the indicated antigen-coated ELISA plates (200 ng/40 μl/well) using pH 7.3 binding buffer. The bound scFv antibodies were detected using a biotinylated anti-E tag monoclonal antibody (1:1000) followed by the addition of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1:1000). Data represent the mean values ±S.D.

PBR7 and PBR30 scFv were then purified by affinity column and tested for their binding specificity using a pH 7.3 buffer (Fig. 2B). Both scFv clearly showed marked binding activity to the β-form but not the α-form of PrP or an unrelated negative control protein, His-tagged human TIM-3.

It is possible that the pH of the experimental condition influences the conformation of PrPs or scFv, resulting in gain or loss of the binding activity. Therefore, to examine more carefully the effects of the pH condition on PrP/scFv binding, after plates had been coated with folded PrP at the corresponding pH, ELISA was performed for 1 h under either pH 4.0 or 8.0. The almost identical results indicated that the binding of PRB7 and PRB30 was specific to β-form but not α-form PrP (supplemental Fig. S4). In concert with the conformation specificity of these clones, they showed no binding activity to the SDS-denatured form of full-length PrP, indicating that both scFv are specific to the conformational structures of β-form PrP (data not shown). It was confirmed that PRB7 reacted with the β-form PrP in native PAGE (supplemental Fig. S5).

Gene Usage of PRB7 and PRB30

The amino acid sequence of scFv clones was deduced from the DNA sequence. The complementarity-determining regions (CDR1–CDR3) and the frame regions (FR1–FR4) were assigned by searching the IMGT/V-QUEST database. PRB7 and PRB30 have unique sequences in both Vh and Vl genes, respectively (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Amino acid sequence analysis of identified scFv specific to β-PrP. A, Vh domains. B, Vl domains. C, the germ line gene usage of anti-β-PrP scFv. Given are the names of the gene segments according to the IMGT database. *, other possibilities: IGHJ5*01 and IGHJ4*01 (highest number of consecutive identical nucleotides) or IGHJ4*01 (shorter alignment but highest percentage of identity).

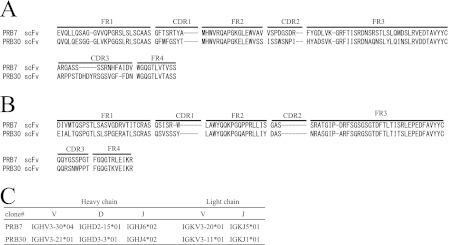

PRB7 and PRB30 Recognize Conformation of β-Form PrP Monomer and Oligomer but Not That of α-Form PrP

PrP was fractionated by size exclusion chromatography. The α-form of PrP was eluted as a single peak (α-form PrP fraction 1) at an elution time of 11.8 min in a running buffer at pH 5.0 (20 mm sodium acetate, 200 mm sodium chloride, 1 m urea, 0.02% azide). For the β-form of PrP, the sample was resolved as two peaks at an elution time of 7.5 (β-form PrP fraction 1) and 12.6 min (β-form PrP fraction 2) in a running buffer at pH 4.0 (20 mm sodium acetate, 200 mm sodium chloride, 1 m urea, 0.02% azide) (Fig. 4A). α-Form PrP fraction 1 exhibited a typical α-helical spectrum, whereas β-form PrP fraction 1 and β-form PrP fraction 2 exhibited a typical β-sheet structure in CD analysis (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

PRB7 and PRB30 scFv recognize β-form PrP monomer and oligomer fractionated by SEC. A, SEC profile of α-form PrP (left) and β-form PrP (right). α-Form PrP or β-form PrP was eluted with a running buffer in the presence of 1 m urea at pH 5.5 or a running buffer in the presence of 1 m urea at pH 4.0, respectively. B, CD spectra of SEC-fractionated samples. The CD signals at wavelengths below 200 nm (not shown) are distorted as a result of absorption by urea. C, the scFv antibodies were added to wells coated with SEC-fractionated samples. PRB7 or PRB30 scFv antibody recognized β-form PrP-Fr1 and β-form PrP-Fr2 but not α-form PrP-Fr1, amyloid β42 peptide, or IL-18. Unrelated scFv (RE51) showed no binding activity to any of these proteins. Data represent the mean values ±S.D. Cont., control; deg, degrees.

To test the binding activity of these fractions to PRB7 and PRB30, each fraction was immobilized on microtiter plates. As shown in Fig. 4C, PRB7 or PRB30 bound to β-form PrP fraction 1 as well as β-form PrP fraction 2. Both scFv showed no binding to α-form PrP, amyloid β42 monomer peptide, IL-18, or BSA. In contrast, the authentic mouse anti-PrP monoclonal antibody SAF32 bound to every PrP fraction irrespectively of their conformations. Its binding epitope is located at the N-terminal octarepeat region of the α-form of PrP (27). Unrelated scFv (RE51) gave no binding reactions to any coated proteins.

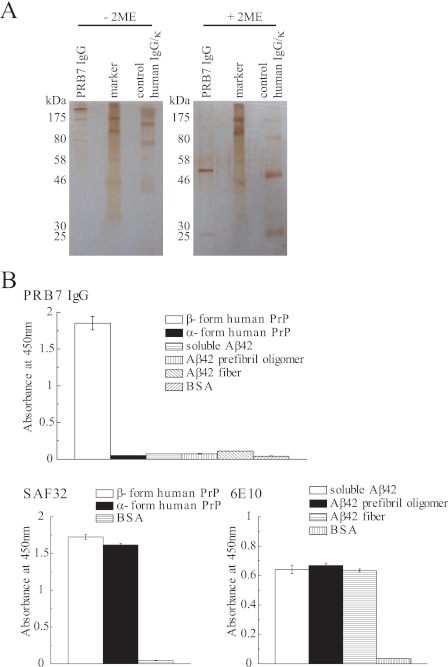

PRB7 IgG and Its Binding Specificity

IgG form of PBR7 scFv was constructed to endow PRB7 scFv with molecular stability. PRB7 IgG purified with a Protein A column was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, which indicated that the IgG form associated with a γ- and κ-chain with a disulfide bond (Fig. 5A). The PRB7 IgG showed an identical binding specificity to PRB7 scFv with specific binding to β-form PrP but not α-form PrP, whereas SAF32 bound equally to β-form PrP and α-form PrP (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, PRB7 IgG showed no binding activity to Aβ42 soluble form, prefibril oligomers, or fibril forms (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Characterization of PRB7 IgG antibody. A, SDS-PAGE of PRB7 IgG. Protein A column-purified PRB7 IgG (300 ng) was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing or non-reducing condition and detected by silver staining. B, PrP conformers (50 ng/50 μl/well) were detected by PRB7 IgG or SAF32 (0.5 μg/ml). Aβ42 conformers (50 ng/50 μl/well) were tested for binding reactivity to PRB7 IgG or 6E10 (mouse anti-Aβ42 antibody) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” 2ME, 2-mercaptoethanol. Data represent the mean values ±S.D.

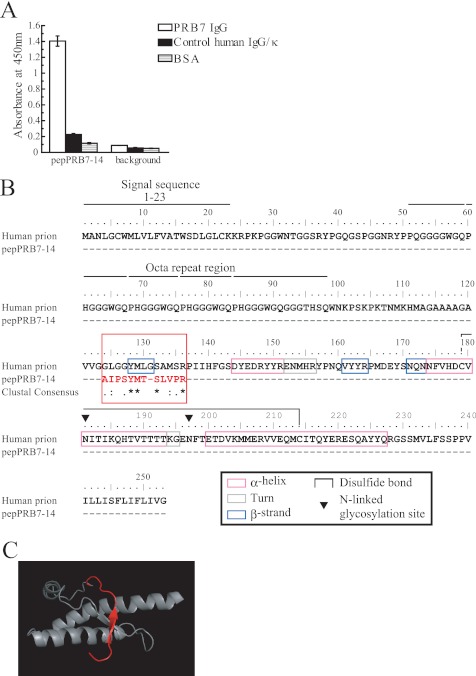

Epitope Mapping of PBR7 IgG

Epitope mapping was performed using a linear peptide-displaying phage library (Ph.D.-12) and a circular peptide-displaying phage library (Ph.D.-C7C). PRB7 IgG-binding clones (pepPRB7-14) were isolated from Ph.D.-12 among 70 clones tested, whereas no clone was selected from Ph.D.-C7C. The binding activity of PBR7 IgG to the pepPRB7-14 clone is shown in Fig. 6A.

FIGURE 6.

Epitope mapping of PRB7 IgG. A, peptide phage clones (50 μl/well of 1 × 1011 virions/ml) were incubated with PRB7 IgG (50 ng/50 μl/well). The bound peptide phage clones were detected using a biotinylated anti-M13 monoclonal antibody (1:2000) followed by HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1:2000). The pepPRB7-14 was selected from a Ph.D.-12 peptide phage library. Data represent the mean values ±S.D. B, amino acid sequence homology between the full-length human PrP and pepPRB7-14 motif (red) was searched by ClustalW. The matching region (amino acids 124–135) is depicted in the red box. The secondary structures are indicated by explanatory marks as shown in the black box. C, computer simulation model of human α-form PrP (Protein Data Bank code 1QM0). The matching region (amino acids 124–135) containing a highly homologous region (amino acids 128–132) is depicted as a red ribbon. PRB7 IgG does not recognize this structure of α-form PrP.

The amino acid sequence homology search using ClustalW version 3.1 indicated that the pepPRB7-14 peptide motif had weak homology to 124–136, particularly 128–132 of the human full-length prion protein, suggesting that PRB7 IgG recognizes this epitope (Fig. 6B). The 124–136 region is depicted in red in the PyMOL display of the NMR structure of the α-form of PrP (24).

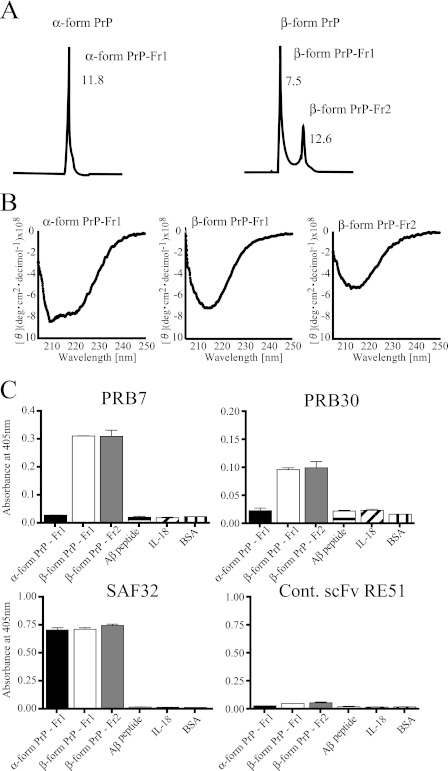

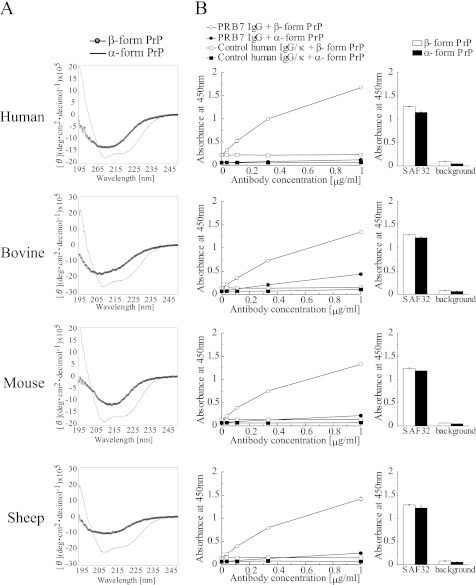

PRB7 IgG Recognizes Common β-Conformation of PrP Shared by Human, Bovine, Sheep, and Mouse

Recombinant PrP of human, bovine, mouse, or sheep was folded according to the protocol of Jackson et al. (12). The CD spectrum of each PrP preparation is shown in Fig. 7A. When the binding activity of PRB7 IgG to these PrPs was examined by ELISA, PRB7 IgG exclusively bound to the β-form of PrP but not the α-form of PrP (Fig. 7B, left panel). This reactivity is shared by human, bovine, sheep, and mouse PrP. SAF32 strongly recognized both forms of every species without any discrimination (Fig. 7B, right panel).

FIGURE 7.

Binding specificity of PRB7 IgG by ELISA analysis. A, CD spectra of α-form PrP and β-form PrP. Recombinant PrP was refolded as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, ELISA of PRB7 IgG antibodies binding to PrP. Left panel, PRB7 IgG (ranging from 0 to 1 μg/ml) was incubated with PrP-coated plates (100 ng/50 μl/well). Normal human IgG was used as a control. The secondary antibody was HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG (1:5000 dilution). Right panel, SAF32 (0.1 μg/ml) equally binds to both α-form PrP and β-form PrP (100 ng/50 μl/well). The background was determined using HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG alone. Data represent the mean values ±S.D. deg, degrees.

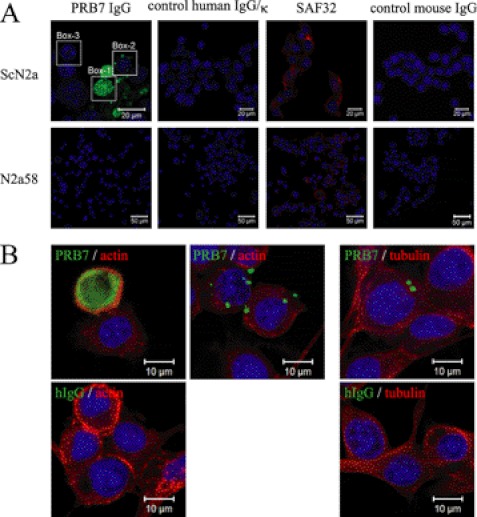

β-Form PrPs Are Generated and Accumulate de Novo in Prion-infected ScN2a Cells

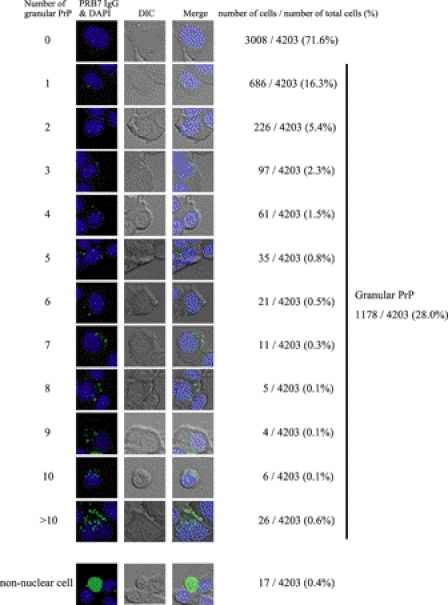

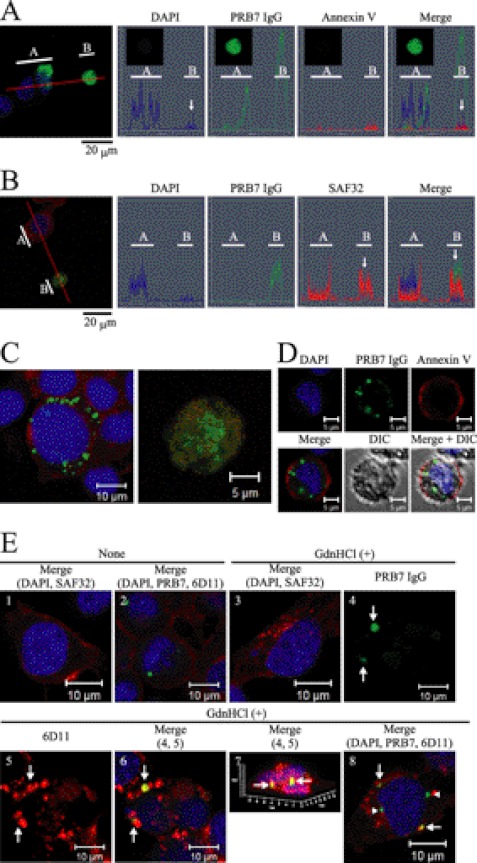

PRB7 recognizes the fine structure of the conformation of PrP and does not stain ScN2a cells fixed with paraformaldehyde. Furthermore, PRB7 IgG hardly stained cell surfaces of non-fixed ScN2a cells, suggesting scarce existence of β-form PrP on the cell surface (supplemental Fig. S6). Therefore, to examine the generation of β-form PrP in prion-infected cells, prion-infected ScN2a cells were cultured in the presence of PRB7 IgG or SAF32. Three days later, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde. After permeation with saponin, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-anti-human IgG to detect the complex of PRB7 IgG-PrP or SAF32-PrP (Fig. 8A). Control cells, N2a58 non-infected cells, or ScN2a cells in the presence of normal IgG were not stained with this protocol. As the binding of normal IgG to N2a58 cells or ScN2a cells was not observed by confocal microscopy or flow cytometry analysis, N2a58 cells or ScN2a cells were found to be Fcγ receptor-negative. In contrast, PRB7 IgG or SAF32 stained the cytoplasm of ScN2a but not N2a58 in a distinct image. Three staining patterns of cytoplasm were observed in ScN2a incubated with PRB7 IgG, i.e. cells with varying numbers of small granules, cells with very large aggregates in the cytoplasm, and cells with no staining. SAF32 stained cell surface PrP of ScN2a and N2a58 cells. When detection sensitivity of confocal laser microscopy was increased, SAF32 was detected by Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-mouse IgG in the cytoplasm region below the cell surface membrane of ScN2a. When these cells were fixed with methanol and stained with anti-β-actin or anti-β-tubulin antibody, the PRB7 IgG-bound aggregates were evident in ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG (Fig. 8B). The details of the PRB7-staining features of ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG are investigated in Fig. 9. About 4000 cells were classified on the basis of the number of stained granules. Cells without granules amounted to 71%, and those with one granule amounted to 16%. Cells with more than 10 granules amounted to 0.6%. Among these cells, 0.4% of cells with very large aggregates in the cytoplasm were particularly conspicuous. Although ScN2a cells with enormous aggregates in the entire cytoplasm were stained with anti-β-actin (Fig. 8B), these cells were analyzed for the existence of nuclei over the perpendicular axis using serial images taken by confocal microscopy, and traces of nuclei were detected by DAPI (Fig. 10A, white arrow). Annexin V weakly stained these cells with enormous aggregates, indicating that these cells had undergone apoptosis, whereas Annexin V did not stain cells that were strongly DAPI-positive (Fig. 10A). When cells with enormous aggregates were stained with SAF32 in addition to PRB7, however, this staining image observed from the perpendicular axis was not completely merged in PRB7- and SAF32-staining PrP (Fig. 10B, white arrow). A magnified image of the B region of Fig. 10B indicated that PRB7 IgG stained very large tangled fibrillary aggregates, whereas SAF32 appeared to independently stain distinctive tiny granules dispersed in the entire cytoplasm (Fig. 10C, right panel). Similarly, in the case of ScN2a cells with clear DAPI-positive nuclei and numerous small PRB7 IgG-bound granules, SAF32 stained another part of the cytoplasm distinct from PRB7 IgG (Fig. 10C, left panel). These cells with a number of tiny PRB7-positive granules were clearly stained with Annexin V, indicating that they had undergone apoptosis (Fig. 10D). These results suggested that PRB7 IgG-bound granules were antibody complexes with N-terminal region-deleted PrP. To confirm whether PRB7 IgG-bound complexes were composed of PrP, ScN2a cells cultured with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled PRB7 IgG were denatured with 6 m GdnHCl and stained with an another anti-PrP antibody, 6D11, which recognizes the epitope located at 93–109 of PrP (32). PrP is sandwiched with PRB7 IgG and 6D11 in ELISA (supplemental Fig. S7). As shown in Fig. 10E, SAF32 or 6D11 did not visualize tiny aggregates in the cytoplasm of non-denatured ScN2a cells, whereas PRB7 IgG stained large aggregates in the same cells (Fig. 10E, panels 1 and 2). In the case of GdnHCl-denatured ScN2a cells, SAF32 or 6D11 stained numerous tiny aggregates in the cytoplasm (Fig. 10E, panels 3 and 5). PRB7 IgG showed a distinct image in the same cells (Fig. 10E, panel 4) where two kinds of staining images were observed, i.e. non-merged and merged aggregates with PRB7 IgG and 6D11 (Fig. 10E, panels 6 and 8). Fig. 10E, panel 7, shows a three-dimensional image of Fig. 10E, panel 6. These results suggested that there were not only PRB7 IgG-bound aggregates that had lost SAF32 and 6D11 epitopes but also 6D11 epitope-retaining aggregates bound with PRB7 IgG.

FIGURE 8.

β-Form PrPs are generated and accumulate de novo in prion-infected ScN2a cells. A, ScN2a or N2a58 cells were cultured in the absence or presence of PRB7 IgG, SAF32, control human IgG/κ, or control mouse IgG (5 μg/ml) in 10% FBS, Opti-MEM. Three days later, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeated for staining with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-human IgG (green), Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-mouse IgG (red), or DAPI (blue) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Each box indicates a representative staining pattern. Box 1, Box 2, and Box 3 show Large/many granules, a few tiny granules, or no granules stained with PRB7 IgG, respectively. B, ScN2a cells cultured in the presence of PRB7 IgG or control human IgG/κ (hIgG) (green) as described in A were fixed with methanol and stained with anti-β-actin antibody (red), anti-β-tubulin antibody (red), or DAPI (blue) as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

FIGURE 9.

Distribution pattern of PRB7 IgG-positive granules in ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG. Cells were stained with PRB7 IgG or DAPI as described in Fig. 8. A total of 4203 cells were classified by the number of granules in the cytoplasm (positive cells/total cells observed). DIC, differential interference contrast.

FIGURE 10.

ScN2a cells exhibit PRB7 IgG-positive aggregates under apoptosis. Cells were stained with PRB7 IgG (green), SAF32 (red), or DAPI (blue) as described in Fig. 8. A, ScN2a cells with very large aggregates in the cytoplasm underwent apoptosis. ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG were incubated with Annexin V (red) followed by fixing, permeation, and staining with anti-human IgG or DAPI as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Orthogonal projections of serial confocal sections are shown by histograms alongside one z-section taken from the middle of the cell (as indicated by the red guidelines). White bar A or B indicates the range of the guideline. The white arrow in the B range indicates the pattern of a huge aggregate-bearing ScN2a cell. Scale bar, 20 μm. B, very large aggregates in the cytoplasm are PrP. ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG were fixed, permeated, and stained with SAF32 followed by secondary antibody staining with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-human IgG or Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-mouse IgG. Orthogonal projections of serial confocal sections are shown by histograms alongside one z-section taken from the middle of the cell (as indicated by the red guidelines). White bar A or B indicates the range of the guideline. The white arrow in the B range indicates the pattern of a huge aggregate-bearing ScN2a cell. C, PRB7 IgG-positive images do not merge with SAF32-positive images. Left image, prion-infected ScN2a cells containing a number of small PRB7 IgG-bound granules. SAF32 stained the entire region of cytoplasm except PRB7 IgG-bound granules. Right image, prion-infected ScN2a cells containing large tangled fibrillary aggregates stained with PRB7 IgG. A number of tiny granules were stained with SAF32 independently of PRB7 IgG-positive aggregates. D, ScN2a cells with a number of PRB7 IgG-positive granules around nuclei underwent apoptosis. ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG were incubated with Annexin V followed by fixing, permeation, and staining with anti-human IgG or DAPI as described in A. E, ScN2a cells cultured with Alexa Fluor 488-PRB7 IgG were fixed, permeated, treated with (+) or without (−) 6 m GdnHCl, and stained with 6D11 (epitope 93–109 of PrP (32)). Panel 1 is an image merged with DAPI and SAF32 staining of non-treated ScN2a cells. Panel 2 is an image merged with DAPI, PRB7 IgG, and 6D11 staining of non-treated ScN2a cells. Panels 3–8 show the images of 6 m GdnHCl-treated ScN2a cells. Panels 4–7 show images of an identical cell. Panel 3 is an image merged with DAPI and SAF32 staining. Panel 4 is an image stained with Alexa Fluor 488-PRB7 IgG. Panel 5 is an image stained with 6D11. Panel 6 is an image merged with PRB7 IgG and 6D11 staining. Panel 7 is a three-dimensional image of panel 6. Panel 8 shows a cell containing heterogeneous PRB7 IgG-bound aggregates merged with (white arrow) or without (white arrowhead) 6D11 staining in the presence of numerous tiny aggregates stained with 6D11 in the cytoplasm. Staining was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” DIC, differential interference contrast.

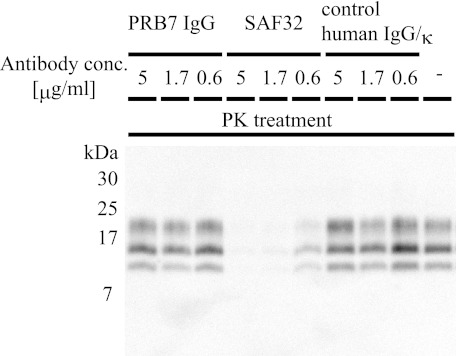

PRB7 IgG Showed No Inhibitory Activity on Accumulation of PrPres in ScN2a Cells

ScN2a cells were cultured in the absence or presence of PRB7 IgG or SAF32. Four days later, cell extracts were prepared in the presence of varying concentrations of PK. The resultant PrPres was evaluated by immunoblotting with 6D11. As shown in Fig. 11, SAF32 strongly inhibited the accumulation of PrPres, indicating the internalization of SAF32 antibody in the cytoplasm after binding to cell surface PrP (Fig. 8). In contrast to the strong inhibitory activity of SAF32, PRB7 IgG showed no effects on the accumulation of PrPres, similar to the effects of control IgG. These results indicated that SAF32 but not PRB7 IgG blocked prion or PrPSc, preventing the generation of β-form PrP.

FIGURE 11.

Effect of PRB7 IgG on accumulation of PrPres. ScN2a cells were cultured with PRB7 IgG, SAF32, or control human IgG/κ antibodies ranging from 0 to 5 μg/ml for 4 days at 37 °C. In the case of “−”, ScN2a was cultured without antibody for 4 days at 37 °C. Cell lysates were treated with PK (final concentration (conc.), 20 μg/ml) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Lysates were separated on a 16.5% Tricine-polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted with 6D11 antibody followed by HRP-conjugated anti-goat mouse IgG as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

DISCUSSION

A number of studies showed that prions generate and accumulate PrPSc, which shows resistance to PK degradation. It is postulated that PrPSc converts PrPC to PrPSc by its templating activity. PrPSc was purified as a multimer or aggregates. The protease-resistant core of PrPSc, designated PrP27–30, polymerizes into an amyloid. Many purified amyloids have been found to have a β-pleated sheet structure. From these findings, it is believed that prion or PrPSc may have a β-sheet-rich structure (3, 5).

Is PrPSc a β-form PrP? Antibodies should be a powerful tool to solve this question. Despite the insufficient biochemical characterization of PrPSc, many attempts have been made to establish antibodies with fine specificity using mice immunized with partially purified PrPSc from prion-infected cells or brain extracts (6, 10, 33–42). However, most antibodies were specific to PrPC or cross-reactive to both PrPC and PrPSc but not monospecific to PrPSc, although more recently a PrPSc-specific murine IgG1 antibody, W261, has been established (10). However, even in this situation, PrP conformation-specific antibodies have not been developed.

In this study, using conformation-defined recombinant β-form PrP and an antibody-displaying phage library, we established a β-form PrP-specific human IgG1 antibody, PRB7 IgG. This antibody does not recognize generic oligomer or aggregate forms of unrelated proteins in accordance with the binding activity of PRB7 or PRB30 scFv. PRB7 IgG is the first human IgG antibody specifically binding to β-form PrP monomer and oligomers but not α-form PrP. It is suggested that PRB7 IgG recognizes the epitope 128–132 of β-form human PrP. PRB7 IgG is equally cross-reactive to the β-form of bovine, sheep, and mouse PrP.

As PRB7 IgG does not recognize paraformaldehyde-fixed or denatured PrP molecules, we simply observed the ScN2a cells cultured with PRB7 IgG. We have demonstrated here that prion-infected ScN2a cells specifically internalized PRB7 IgG and accumulated the PrP granules bound with PRB7 IgG in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8). This is the first direct demonstration that β-form PrP was generated and accumulated in prion-infected cells in the physiological condition. Because neither ScN2a nor N2a58 cells were stained with normal IgG as assessed by confocal microscopy or flow cytometry, these cells were Fcγ receptor-negative. Nevertheless, ScN2a cells internalized PRB7 IgG, suggesting that complexes of β-form PrP targeted by PRB7 IgG localizing on the cell surface were endocytosed into the cytoplasm (29). If this β-form PrP corresponds to PrPSc, this observation is in accordance with the finding that PrPSc was generated on a lipid raft on the cell surface (43). When ScN2a cells were cultured with PRB7 IgG, they gradually generated an increasing number of tiny PRB7-binding granules in the cytoplasm. Among them, about 0.4% of cells had enormous aggregates in the cytoplasm. Vertically severed images of these cells show traces of nuclei in cells that were weakly stained with Annexin V, indicating that they had undergone apoptosis (Fig. 10A). These findings suggested that an enormous aggregate resulted from the fusion of many tiny β-form granules primarily endocytosed from the cell surface but was not the result of β-form PrP propagation in the cytoplasm.

SAF32 bound tiny granules dispersed in the cytoplasm that were distinct from large aggregates stained with PRB7 IgG (Fig. 10C). These results suggested first that PRB7-positive β-form PrPs lost or hid the N-terminal octarepeat region to which SAF32 bound and second that granules stained with SAF32 were not generated from β-form PrP.

It was suggested that PrPC-PrPSc conversion, which is physiologically prevented by an energy barrier, may be a spontaneous stochastic event favored by mutations in the PRNP gene or acquired by infection with exogenous PrPSc. Accordingly, it is conceivable that GdnHCl treatment of cells additively induces the conformational conversion of PrP, leading to the formation of aggregates in experiments that immunohistologically attempted to show granules of PrPSc in the cytoplasm (8). It is noted that when ScN2a cells were stained with SAF32 or 6D11 with a denaturing pretreatment by 6 m GdnHCl numerous tiny PrP granules became visible in the cytoplasm, and their images were quite distinct from those of PRB7-staining aggregates. Our results indicated that apoptotic cells showed two distinct types of PrP granules in the cytoplasm: one was SAF32-negative and PRB7 IgG-positive granules (N-terminal region-deleted; β-form PrP), and the other was PRB7 IgG-negative and SAF32-positive granules (full-length PrP lacking a β-sheet-rich conformation) (Fig. 10E). Related studies have reported that PK-sensitive PrPSc was contained in prion aggregates (44) and more recently that there is heterogeneity in PrPSc conformers including small soluble PrP aggregates (6). Regarding the requirement of full-length PrP for prion activity, the answer is not consistent: i.e. Prusiner et al. (50) reported that the purified PK-digested PrP27–30 was not infectious, whereas Anaya et al. (45) have recently reported that small infectious PrPres aggregates were recovered in the absence of strong in vitro denaturing treatments from prion-infected cultured cells. On the other hand, using an anti-aggregated PrP IgM antibody, 15B3, Biasini et al. (6, 47) reported the successful purification of pathological full-length prion aggregates, and Cronier et al. (46) found that PK-sensitive PrPSc was involved in prion aggregates. Our findings in Fig. 10 suggest that PrP composed of tiny aggregates visualized with SAF32 or 6D11 after 6 m GdnHCl treatment of cells may be a full-length PrP with α-conformation.

To examine the influence of PRB7 IgG on the templating activity of β-form PrP to accumulate PrPSc, ScN2a cells were cultured in the presence of PRB7 IgG or SAF32, and their PK-treated cell lysates were immunoblotted with 6D11 to evaluate the amount of PrPres. Surprisingly, PRB7 IgG had no effect, whereas SAF32 strongly inhibited the generation/accumulation of PrPSc. Similar results have been reported in which a PrPSc-specific antibody had no prion-clearing effect, whereas the PrPC-specific antibody showed marked clearing activity (10). Because the mimotope of PRB7 is located at 128–132, if this β-pleated sheet forms an interface for prion aggregation PRB7 IgG may block the assembly of PrP aggregates because the binding IgG is much larger than the target molecule (PrP). We examined this activity using FF32 cells or N2aL1 cells and obtained the same results as for ScN2a cells (data not shown). In this respect, our result suggested that, in the prion conversion reaction, PRB7 IgG-recognizing β-form PrP did not play a role in driving the conversion of the PrP conformation and appears rather to be an end product that loses prion activity and accumulates in the cytoplasm. This end product may trigger cell cytotoxicity via the mitochondrial machinery (42). This is in concert with the result that β-form recombinant PrP does not work as a template for prion amplification in protein misfolding cyclic amplification (41, 48). It is conceivable that PRB7-negative, SAF32-positive granules as a full-length, non-β-form PrP might be responsible for prion propagation (Fig. 10, C and E). Our results may be in agreement with the finding that prion propagation and toxicity in vivo occur in two distinct mechanistic phases (42). Thus, we have not obtained evidence to determine whether PRB7-recognizing β-form PrP represents the so-called PrPSc that has both conversion activity and cell cytotoxicity. Further investigation is needed to determine whether β-form PrP affinity-purified with PRB7 shows prion activity such as the infectious and conversion/accumulation activity of the prion.

Although a number of studies illuminated the accumulation of PrPres in prion-infected cells or brain extracts, there is little literature giving much attention to the phenomenon in which most prion-infected ScN2a cells vigorously proliferate to survive in culture (49). The low frequency of PRB7 IgG-positive granules in ScN2a cells suggests the stochastic nature of the conversion of α-form to β-form PrP. The spongelike degeneration of prion-infected brain may reflect this feature.

In conclusion, we report the establishment of PRB7 IgG, which is the first human antibody discriminating the β-form from the α-form of PrP in the physiological condition. Using this antibody, we have demonstrated direct evidence of the generation and accumulation of β-form PrP in prion-infected ScN2a cells. It can be used to purify β-form PrP molecules without the need for protease digestion and may be useful to demonstrate the biochemical basis of the relationship of β-form PrP to PrPSc and to elucidate the structure-based evidence for prion infectivity and neurotoxicity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mayumi Yamamoto and Yuko Sato for the initial study on this theme.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research C 16613008 and for Young Scientists B 22790435 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (to S. H.), Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants on Food Safety (Shokuhin-016) (to S. H.) and Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (to S. H. and K. S.), a grant-in-aid from the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Control Project of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (to K. S.), and Super Special Consortia for supporting the development of cutting-edge medical care from 2008 to 2012 (to K. S.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

- PrP

- prion protein

- PK

- proteinase K

- Vhls

- heavy-chain leader sequence

- Vh

- heavy-chain variable gene

- Vl

- light-chain variable gene

- Vlls

- light-chain leader sequence

- scFv

- single chain Fv(s)

- IGHC1

- human immunoglobulin heavy chain 1

- IGKC

- human immunoglobulin κ-chain

- ScN2a

- Scrapie-infected neuroblastoma

- rPrP

- recombinant full-length prion protein

- GdnHCl

- guanidine hydrochloride

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- SEC

- size exclusion chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1. Prusiner S. B. (1998) Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13363–13383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rogers M., Yehiely F., Scott M., Prusiner S. B. (1993) Conversion of truncated and elongated prion proteins into the scrapie isoform in cultured cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3182–3186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan K. M., Baldwin M., Nguyen J., Gasset M., Serban A., Groth D., Mehlhorn I., Huang Z., Fletterick R. J., Cohen F. E.(1993) Conversion of α-helices into β-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 10962–10966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prusiner S. B., McKinley M. P., Bowman K. A., Bolton D. C., Bendheim P. E., Groth D. F., Glenner G. G. (1983) Scrapie prions aggregate to form amyloid-like birefringent rods. Cell 35, 349–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turk E., Teplow D. B., Hood L. E., Prusiner S. B. (1988) Purification and properties of the cellular and scrapie hamster prion proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 176, 21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biasini E., Tapella L., Mantovani S., Stravalaci M., Gobbi M., Harris D. A., Chiesa R. (2009) Immunopurification of pathological prion protein aggregates. PLoS One 4, e7816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wadsworth J. D., Joiner S., Hill A. F., Campbell T. A., Desbruslais M., Luthert P. J., Collinge J. (2001) Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease using a highly sensitive immunoblotting assay. Lancet 358, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bocharova O. V., Breydo L., Parfenov A. S., Salnikov V. V., Baskakov I. V. (2005) In vitro conversion of full-length mammalian prion protein produces amyloid form with physical properties of PrP(Sc). J. Mol. Biol. 346, 645–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khalili-Shirazi A., Kaisar M., Mallinson G., Jones S., Bhelt D., Fraser C., Clarke A. R., Hawke S. H., Jackson G. S., Collinge J. (2007) β-PrP form of human prion protein stimulates production of monoclonal antibodies to epitope 91–110 that recognise native PrPSc. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774, 1438–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petsch B., Müller-Schiffmann A., Lehle A., Zirdum E., Prikulis I., Kuhn F., Raeber A. J., Ironside J. W., Korth C., Stitz L. (2011) Biological effects and use of PrPSc- and PrP-specific antibodies generated by immunization with purified full-length native mouse prions. J. Virol. 85, 4538–4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ishibashi D., Yamanaka H., Yamaguchi N., Yoshikawa D., Nakamura R., Okimura N., Yamaguchi Y., Shigematsu K., Katamine S., Sakaguchi S. (2007) Immunization with recombinant bovine but not mouse prion protein delays the onset of disease in mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted prion. Vaccine 25, 985–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson G. S., Hosszu L. L., Power A., Hill A. F., Kenney J., Saibil H., Craven C. J., Waltho J. P., Clarke A. R., Collinge J. (1999) Reversible conversion of monomeric human prion protein between native and fibrilogenic conformations. Science 283, 1935–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamasaki T., Hashiguchi S., Ito Y., Kato Z., Nakanishi K., Nakashima T., Sugimura K. (2005) Human anti-human IL-18 antibody recognizing the IL-18-binding site 3 with IL-18 signaling blocking activity. J. Biochem. 138, 433–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanaka K., Nishimura M., Yamaguchi Y., Hashiguchi S., Takiguchi S., Yamaguchi M., Tahara H., Gotanda T., Abe R., Ito Y., Sugimura K. (2011) A mimotope peptide of Aβ42 fibril-specific antibodies with Aβ42 fibrillation inhibitory activity induces anti-Aβ42 conformer antibody response by a displayed form on an M13 phage in mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 236, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hashiguchi S., Nakashima T., Nitani A., Yoshihara T., Yoshinaga K., Ito Y., Maeda Y., Sugimura K. (2003) Human FcϵRIα-specific human single-chain Fv (scFv) antibody with antagonistic activity toward IgE/FcϵRIα-binding. J. Biochem. 133, 43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoshihara T., Takiguchi S., Kyuno A., Tanaka K., Kuba S., Hashiguchi S., Ito Y., Hashimoto T., Iwatsubo T., Tsuyama S., Nakashima T., Sugimura K. (2008) Immunoreactivity of phage library-derived human single-chain antibodies to amyloid β conformers in vitro. J. Biochem. 143, 475–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williamson R. A., Peretz D., Smorodinsky N., Bastidas R., Serban H., Mehlhorn I., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B., Burton D. R. (1996) Circumventing tolerance to generate autologous monoclonal antibodies to the prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 7279–7282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williamson R. A., Peretz D., Pinilla C., Ball H., Bastidas R. B., Rozenshteyn R., Houghten R. A., Prusiner S. B., Burton D. R. (1998) Mapping the prion protein using recombinant antibodies. J. Virol. 72, 9413–9418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peretz D., Williamson R. A., Matsunaga Y., Serban H., Pinilla C., Bastidas R. B., Rozenshteyn R., James T. L., Houghten R. A., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B., Burton D. R. (1997) A conformational transition at the N terminus of the prion protein features in formation of the scrapie isoform. J. Mol. Biol. 273, 614–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gerber R., Tahiri-Alaoui A., Hore P. J., James W. (2007) Oligomerization of the human prion protein proceeds via a molten globule intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6300–6307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boel E., Verlaan S., Poppelier M. J., Westerdaal N. A., Van Strijp J. A., Logtenberg T. (2000) Functional human monoclonal antibodies of all isotypes constructed from phage display library-derived single-chain Fv antibody fragments. J. Immunol. Methods 239, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yoshinaga K., Matsumoto M., Torikai M., Sugyo K., Kuroki S., Nogami K., Matsumoto R., Hashiguchi S., Ito Y., Nakashima T., Sugimura K. (2008) Ig L-chain shuffling for affinity maturation of phage library-derived human anti-human MCP-1 antibody blocking its chemotactic activity. J. Biochem. 143, 593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu C., Dalby B., Chen W., Kilzer J. M., Chiou H. C. (2008) Transient transfection factors for high-level recombinant protein production in suspension cultured mammalian cells. Mol. Biotechnol. 39, 141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zahn R., Liu A., Lührs T., Riek R., von Schroetter C., López García F., Billeter M., Calzolai L., Wider G., Wüthrich K. (2000) NMR solution structure of the human prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishikawa K., Doh-ura K., Kudo Y., Nishida N., Murakami-Kubo I., Ando Y., Sawada T., Iwaki T. (2004) Amyloid imaging probes are useful for detection of prion plaques and treatment of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 1785–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Atarashi R., Sim V. L., Nishida N., Caughey B., Katamine S. (2006) Prion strain-dependent differences in conversion of mutant prion proteins in cell culture. J. Virol. 80, 7854–7862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Féraudet C., Morel N., Simon S., Volland H., Frobert Y., Créminon C., Vilette D., Lehmann S., Grassi J. (2005) Screening of 145 anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies for their capacity to inhibit PrPSc replication in infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11247–11258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kristiansen M., Messenger M. J., Klöhn P. C., Brandner S., Wadsworth J. D., Collinge J., Tabrizi S. J. (2005) Disease-related prion protein forms aggresomes in neuronal cells leading to caspase activation and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38851–38861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Veith N. M., Plattner H., Stuermer C. A., Schulz-Schaeffer W. J., Bürkle A. (2009) Immunolocalisation of PrPSc in scrapie-infected N2a mouse neuroblastoma cells by light and electron microscopy. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 88, 45–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goold R., Rabbanian S., Sutton L., Andre R., Arora P., Moonga J., Clarke A. R., Schiavo G., Jat P., Collinge J., Tabrizi S. J. (2011) Rapid cell-surface prion protein conversion revealed using a novel cell system. Nat. Commun. 2, 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sasaki K., Gaikwad J., Hashiguchi S., Kubota T., Sugimura K., Kremer W., Kalbitzer H. R., Akasaka K. (2008) Reversible monomer-oligomer transition in human prion protein. Prion 2, 118–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pankiewicz J., Prelli F., Sy M. S., Kascsak R. J., Kascsak R. B., Spinner D. S., Carp R. I., Meeker H. C., Sadowski M., Wisniewski T. (2006) Clearance and prevention of prion infection in cell culture by anti-PrP antibodies. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2635–2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Korth C., Stierli B., Streit P., Moser M., Schaller O., Fischer R., Schulz-Schaeffer W., Kretzschmar H., Raeber A., Braun U., Ehrensperger F., Hornemann S., Glockshuber R., Riek R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K., Oesch B. (1997) Prion (PrPSc)-specific epitope defined by a monoclonal antibody. Nature 390, 74–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ushiki-Kaku Y., Endo R., Iwamaru Y., Shimizu Y., Imamura M., Masujin K., Yamamoto T., Hattori S., Itohara S., Irie S., Yokoyama T. (2010) Tracing conformational transition of abnormal prion proteins during interspecies transmission by using novel antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11931–11936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Beringue V., Vilette D., Mallinson G., Archer F., Kaisar M., Tayebi M., Jackson G. S., Clarke A. R., Laude H., Collinge J., Hawke S. (2004) PrPSc binding antibodies are potent inhibitors of prion replication in cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39671–39676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stanker L. H., Serban A. V., Cleveland E., Hnasko R., Lemus A., Safar J., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2010) Conformation-dependent high-affinity monoclonal antibodies to prion proteins. J. Immunol. 185, 729–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Skrlj N., Vranac T., Popović M., Curin Šerbec V., Dolinar M. (2011) Specific binding of the pathogenic prion isoform: development and characterization of a humanized single-chain variable antibody fragment. PLoS One 6, e15783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kosmač M., Koren S., Giachin G., Stoilova T., Gennaro R., Legname G., Serbec V. Č. (2011) Epitope mapping of a PrP(Sc)-specific monoclonal antibody: identification of a novel C-terminally truncated prion fragment. Mol. Immunol. 48, 746–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sasamori E., Suzuki S., Kato M., Tagawa Y., Hanyu Y. (2010) Characterization of discontinuous epitope of prion protein recognized by the monoclonal antibody T2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 501, 232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horiuchi M., Karino A., Furuoka H., Ishiguro N., Kimura K., Shinagawa M. (2009) Generation of monoclonal antibody that distinguishes PrPSc from PrPC and neutralizes prion infectivity. Virology 394, 200–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saá P., Castilla J., Soto C. (2006) Ultra-efficient replication of infectious prions by automated protein misfolding cyclic amplification. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35245–35252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sandberg M. K., Al-Doujaily H., Sharps B., Clarke A. R., Collinge J. (2011) Prion propagation and toxicity in vivo occur in two distinct mechanistic phases. Nature 470, 540–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hnasko R., Serban A. V., Carlson G., Prusiner S. B., Stanker L. H. (2010) Generation of antisera to purified prions in lipid rafts. Prion 4, 94–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. D'Castro L., Wenborn A., Gros N., Joiner S., Cronier S., Collinge J., Wadsworth J. D. (2010) Isolation of proteinase K-sensitive prions using pronase E and phosphotungstic acid. PLoS One 5, e15679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anaya Z. E., Savistchenko J., Massonneau V., Lacroux C., Andréoletti O., Vilette D. (2011) Recovery of small infectious PrP(res) aggregates from prion-infected cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8141–8148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cronier S., Gros N., Tattum M. H., Jackson G. S., Clarke A. R., Collinge J., Wadsworth J. D. (2008) Detection and characterization of proteinase K-sensitive disease-related prion protein with thermolysin. Biochem. J. 416, 297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Biasini E., Seegulam M. E., Patti B. N., Solforosi L., Medrano A. Z., Christensen H. M., Senatore A., Chiesa R., Williamson R. A., Harris D. A. (2008) Non-infectious aggregates of the prion protein react with several PrPSc-directed antibodies. J. Neurochem. 105, 2190–2204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saborio G. P., Permanne B., Soto C. (2001) Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature 411, 810–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Uryu M., Karino A., Kamihara Y., Horiuchi M. (2007) Characterization of prion susceptibility in Neuro2a mouse neuroblastoma cell subclones. Microbiol. Immunol. 51, 661–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Prusiner S. B., Groth D. F., Bolton D. C., Kent S. B., Hood L. E. (1984) Purification and structural studies of a major scrapie prion protein. Cell 38, 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.