Background: Regulation of terminal chondrocyte differentiation is important for bone development and cartilage pathology.

Results: Annexin A6 regulates terminal chondrocyte differentiation by modulating key signaling pathway activities.

Conclusion: Annexin A6 acts an intracellular regulator of terminal chondrocyte differentiation.

Significance: The understanding of the mechanisms that regulate terminal chondrocyte differentiation is crucial for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of cartilage diseases.

Keywords: Annexin, Chondrocytes, Differentiation, Growth Plate, Signaling

Abstract

Annexin A6 (AnxA6) is highly expressed in hypertrophic and terminally differentiated growth plate chondrocytes. Rib chondrocytes isolated from newborn AnxA6−/− mice showed delayed terminal differentiation as indicated by reduced terminal differentiation markers, including alkaline phosphatase, matrix metalloproteases-13, osteocalcin, and runx2, and reduced mineralization. Lack of AnxA6 in chondrocytes led to a decreased intracellular Ca2+ concentration and protein kinase C α (PKCα) activity, ultimately resulting in reduced extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activities. The 45 C-terminal amino acids of AnxA6 (AnxA6(1–627)) were responsible for the direct binding of AnxA6 to PKCα. Consequently, transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with full-length AnxA6 rescued the reduced expression of terminal differentiation markers, whereas transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with AnxA6(1–627) did not or only partially rescued the decreased mRNA levels of terminal differentiation markers. In addition, lack of AnxA6 in matrix vesicles, which initiate the mineralization process in growth plate cartilage, resulted in reduced alkaline phosphatase activity and Ca2+ and inorganic phosphate (Pi) content and the inability to form hydroxyapatite-like crystals in vitro. Histological analysis of femoral, tibial, and rib growth plates from newborn mice revealed that the hypertrophic zone of growth plates from newborn AnxA6−/− mice was reduced in size. In addition, reduced mineralization was evident in the hypertrophic zone of AnxA6−/− growth plate cartilage, although apoptosis was not altered compared with wild type growth plates. In conclusion, AnxA6 via its stimulatory actions on PKCα and its role in mediating Ca2+ flux across membranes regulates terminal differentiation and mineralization events of chondrocytes.

Introduction

Annexin A6 (AnxA6)2 belongs to the highly conserved annexin protein family. Like the other annexins, AnxA6 functions are mostly linked to its ability to bind phospholipids in a Ca2+-dependent manner (1). The annexins have been shown to be involved in a diverse range of cellular functions both inside the cell and extracellularly, including membrane-related events and membrane-trafficking events, ion channel activity, inflammation, and fibrinolysis (1, 2). All annexins consist of a highly variable N-terminal domain and a more conserved core domain. The core domain contains four repeat units; an exception is the core domain of AnxA6, which contains eight repeat units (2). AnxA6 is highly expressed in the zones of hypertrophic and terminally differentiated growth plate chondrocytes (3).

During endochondral bone formation, chondrocytes in the growth plate undergo a series of differentiation events, including proliferation, prehypertrophy, hypertrophy, terminal differentiation, and ultimately programmed cell death (apoptosis). These events, which are highly regulated both spatially and temporally, are characterized by the expression of specific genes. Proliferative chondrocytes express type II (type IIB form), IX, and XI collagens and aggrecan as their major matrix components. When chondrocytes become hypertrophic, they reduce the expression of type II and IX collagens and begin expression of type X collagen. In addition, these cells express runx2, a transcription factor, which is a major regulator of hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events. Hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo terminal differentiation, which is characterized by the expression of terminal differentiation marker genes, including alkaline phosphatase (APase), matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13), and osteocalcin, and mineralization (4).

The factors and signaling pathways involved in the regulation of the various differentiation steps of growth plate chondrocytes are a matter of intense investigations. Previous studies have shown that ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways play crucial roles in the regulation of hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes. Shimo et al. (5) have shown that ERK exerts a positive role in posthypertrophy and terminal differentiation, whereas p38 has a positive role earlier in the differentiation process, namely in the hypertrophic stage.

Recent studies have demonstrated that AnxA6 via acting as a scaffolding and targeting protein regulates the formation of compartment-specific signaling complexes. For example, AnxA6 interacts with p120GAP and recruits p120GAP to the membrane to modulate Ras and Raf-1 activity (6). AnxA6 also interacts with active PKCα, and these interactions stimulate ERK-MAPK signaling pathway activation (7, 8). As discussed above, the ERK-MAPK signaling pathway plays an essential role in the regulation of growth plate chondrocyte differentiation events, including hypertrophic and terminal differentiation (5). These findings suggest that AnxA6 may play a crucial role in growth plate chondrocyte hypertrophic and terminal differentiation in vivo and that AnxA6 regulates these events by acting as a scaffolding protein that regulates the formation of signaling complexes. To determine the exact roles of AnxA6 in growth plate chondrocyte hypertrophic and terminal differentiation, we analyzed growth plate cartilage in AnxA6 knock-out (AnxA6−/−) mice and determined hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

The AnxA6−/− mice were provided to us by Dr. S. E. Moss, University College of London, London, UK. These mice have a C57BL/6 genetic background, and mice heterozygous for the mutation in AnxA6 were used for breeding (9). All protocols involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and New York University School of Medicine.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

For histomorphometric analysis, hind limbs from 10 newborn AnxA6−/− mice and 10 wild type littermates were used. Dissected knee joints from AnxA6−/− mice and wild type littermates were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde; decalcified in 0.2 m EDTA, pH 7.4; and embedded in paraffin. Eight-micrometer sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The lengths of the different zones of the growth plate were analyzed by histomorphometry using OsteoMeasure software (OsteoMetrics, Inc., Decatur, GA) in an epifluorescence microscopic system. Images were acquired with a microscope (Olympus IX71, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) and 10× or 20× objectives (Olympus), and a digital camera with a 0.7× reduction lens (Sony Color Video Camera 3CCD, Sony, New York, NY) was used for photography.

Immunohistochemistry

Growth plate sections were pretreated with bovine testicular hyaluronidase (2 mg/ml; Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C, blocked with goat serum for 20 min at room temperature, and incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies specific for phospho-p44/42, total p44/42, phospho-p38, or total p38 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA). After washing, sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) for 1 h. They were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus). Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI).

TUNEL Labeling

Apoptotic cells were identified by using a TUNEL-based in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Diagnostics). After treatment with 10 μg/ml proteinase K for 30 min at 37 °C, sections were incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture for 2 h at 37 °C, rinsed, and mounted.

Cell Cultures

Chondrocytes were isolated from rib cartilage of newborn AnxA6−/− mice and wild type littermates as described previously (10). Cells were plated at a density of 3 × 106 into 100-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes and grown in monolayer cultures in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 1 g/liter glucose, 5% fetal calf serum (FCS; HyClone, Logan, Utah), 2 mm l-glutamine (Invitrogen), and 50 units/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen) (complete medium). Semiconfluent chondrocytes were transfected with empty pcDNA expression vector or pcDNA expression vector containing AnxA6 cDNA using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Applied Science). We used the pcDNA vector, which contains a c-myc tag. We obtained a transfection rate between 40 and 50% as determined by immunostaining of transfected cells with FITC-labeled antibodies specific for c-Myc (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and counterstaining of cell nuclei with DAPI. Co-immunostaining with antibodies specific for type X collagen (hypertrophic marker) revealed that hypertrophic chondrocytes were equally well transfected as non-hypertrophic chondrocytes (data not shown). Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm inorganic phosphate (Pi), a myristoylated protein kinase C inhibitor 20–28 (PKC(20–28); specific PKCα inhibitor; 10 μm; Calbiochem), PD98059 (specific ERK inhibitor; 10 μm; Millipore, Billerica, MA), or SB203580 (specific p38 inhibitor; 10 μm; Millipore). After 6 days of culture, cells were stained for APase activity using alkaline phosphatase magenta immunohistochemical substrate solution (Sigma), or APase activity was determined in cell lysates using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate as described previously (11).

Transfection and Luciferase Reporter Assays

For luciferase assays, cells were co-transfected with empty pcDNA or pcDNA containing AnxA6 cDNA and a firefly luciferase reporter construct containing six runx2 DNA-binding elements (pOSE2-Luc). After 48 or 72 h, the cells were rinsed in PBS and lysed in 1× passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase activity was monitored based on the Dual-LuciferaseTM reporter assay system (Promega) using a Tristar LB 941 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Oak Ridge, TN). Transfection efficiency was monitored by co-transfection with pRL vector (Promega), which provides constitutive expression of Renilla luciferase. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three to five times.

Measurement of Intracellular Ca2+ Concentration ([Ca2+]i)

Chondrocytes, after reaching confluency, were treated for 5 days with ascorbic acid and 1.5 mm additional phosphate to induce hypertrophy and the expression of annexins A2, A5, and A6 (11). Cells were trypsinized, and then 2 × 106 cells were incubated with 4 μm fura-2AM (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 15 min in complete medium. [Ca2+]i was measured and calculated as described previously (12).

RT-PCR and Real Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from growth plate chondrocyte cultures by using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). mRNA levels of aggrecan, APase, MMP-13, osteocalcin, runx2, Sox-9, and type II and X collagens were quantified by real time PCR as described previously (13). Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed by using an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen). A 1:100 dilution of the resulting cDNA was used as the template to quantify the relative content of mRNA by real time PCR (ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the respective primers and SYBR Green. The following primers were used for real time PCR analysis: APase forward primer, 5′-CCC TGA CAT CGA GGT GAT CCT-3′; APase reverse primer, 5′-GGT ACT CCA CAT CGC TGG TGT T-3′; collagen type X forward primer, 5′-AGT GCT GTC ATT GAT CTC ATG GA-3′; collagen type X reverse primer, 5′-TCA GAG GAA TAG AGA CCA TTG GAT T-3′; MMP-13 forward primer, 5′-TGG ATG GAC CCT CTG GAT TAC TG-3′; MMP-13 reverse primer, 5′-CAA AAT GGG CAT CTC CTC CAT A-3′; runx2 forward primer, 5′-CGC GGA GCT GCG AAA T-3′; runx2 reverse primer, 5′-ACG AAT CGC AGG TCA TTG AAT-3′; osteocalcin forward primer, 5′-TCG CGG CGC TGC TCA CAT TCA-3′; and osteocalcin reverse primer, 5′-TGG CGG TGG GAG ATG AAG GCT TTA-3′. PCRs were performed with a TaqMan PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems) with 40 cycles at 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. The 18 S RNA was amplified at the same time and used as an internal control. The cycle threshold values for 18 S RNA and the samples were measured and calculated by computer software. Relative transcript levels were calculated as x = 2−ΔΔCt in which ΔΔCt = ΔE − ΔC, ΔE = Ctexp − Ct18 S, and ΔC = Ctctl − Ct18 S.

Isolation of Matrix Vesicles (MVs) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

MVs were isolated from chondrocytes cultured for 2 weeks in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi as described previously (11). Briefly, adherent chondrocytes were washed with PBS and then incubated in PBS containing 0.1% trypsin (type III; Sigma) at 37 °C for 30 min. The trypsin was removed by washing with PBS, and the cells were then treated with crude collagenase (500 units/ml; type IA; Sigma) at 37 °C for 3 h. Matrix vesicles were harvested by differential ultracentrifugation as described previously (14). Three dishes (100 mm) of confluent chondrocyte cultures were used to isolate MV fractions containing between 300 and 500 μg of total proteins. For mineralization studies, MVs (50 μg of total protein) were resuspended in 500 μl of synthetic cartilage lymph and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Synthetic cartilage lymph, pH 7.4 contained 2 mm Ca2+ and 1.42 mm Pi in addition to 104.5 mm Na+, 133.5 mm Cl−, 63.5 mm sucrose, 16.5 mm Tris, 12.70 mm K+, 5.55 mm d-glucose, 1.83 mm HCO3−, 0.57 mm Mg2+, and 0.57 mm SO42−. APase activity in the vesicle fractions was determined using p-nitrophenyl phosphate and normalized to the total protein content as described previously (14). To measure calcium and phosphate levels, vesicle fractions were resuspended in 0.1 m HCl, and calcium and inorganic phosphate were measured using spectrophotometric methods described previously (14). For Fourier transform infrared spectroscopical analysis, MV samples were freeze-dried and stored desiccated. Each sample was analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Magna IR 550 spectrometer, Nicolet Instrument Technologies, Madison, WI) operated in the diffuse reflectance mode. Vesicle preparations were milled in an agate mortar and layered on KBr (ratio of KBr to sample, 300:1, w/w); routinely, 300 interferograms were collected at 4-cm−1 resolutions; and background was subtracted using a chondrocyte membrane preparation. Spectra were co-added, and the resultant interferograms were Fourier transformed. Second derivative spectra were obtained using a software package (Omnic, Nicolet Instrument Technologies).

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

To determine the amount of phosphorylated and total PKCα, ERK, and p38 or AnxA2, AnxA5, and AnxA6 in MVs, cell lysates or MV fractions were dissolved in 4× NuPAGE SDS sample buffer containing a reducing agent (Invitrogen), denatured at 70 °C for 10 min, and analyzed by electrophoresis in 10% bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels. Samples were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose filters after electrophoresis. After blocking with a solution of low fat milk protein, blotted proteins were immunostained with primary antibodies specific for phosphorylated or total PKCα, ERK, or p38 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and then peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) as previously described (13). To determine the amount of phosphorylated and total membrane-associated PKCα, membrane-associated proteins were extracted using the Subcellular Protein Fractionation kit (Pierce Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer's instructions. The isolated membrane protein fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot using antibodies specific for phosphorylated and total PKCα (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). To determine the amount of AnxA2, AnxA5, or AnxA6 protein, total cell lysates or MV fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for AnxA2, AnxA5, or AnxA6 as described previously (13).

Statistical Analysis

Student's t tests were performed to evaluate differences between two groups; analysis of variance was used for three or more groups. Tukey's multiple comparison test was applied as a post hoc test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Loss of AnxA6 Delays Terminal Differentiation Events of Chondrocytes

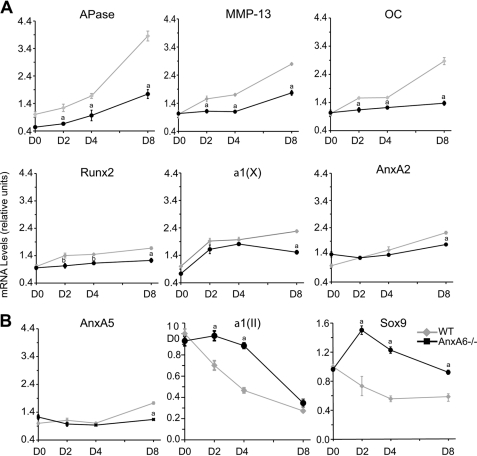

We isolated rib chondrocytes from newborn AnxA6−/− mice and wild type littermates and cultured these cells in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi. During development, chondrocytes undergo hypertrophic followed by terminal differentiation and mineralization. Ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi have been shown to stimulate hypertrophic, terminal, and mineralization events of chondrocytes (11, 15). Real time PCR analysis revealed that the mRNA levels of hypertrophic and terminal differentiation marker genes, including APase, type X collagen, MMP-13, osteocalcin, and runx2, increased during the 8-day culture period in wild type and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes (Fig. 1A). The mRNA levels of hypertrophic markers (runx2 and type X collagen) in the chondrocyte cultures were already high at the beginning of the treatment with ascorbic acid and 1.5 mm Pi, indicating that the majority of chondrocytes had reached hypertrophy when the treatment with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi was started. Consequently, the increase of the mRNA levels of hypertrophic markers was markedly less pronounced than the increase of terminal differentiation mRNA levels (Fig. 1A). The increase of mRNA levels of terminal differentiation marker genes, including APase, MMP-13, and osteocalcin, however, was markedly decreased in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes especially after 8 days of culture compared with the levels of wild type cells, whereas the mRNA levels of hypertrophic marker genes, including runx2 and type X collagen, decreased to a lesser degree than terminal differentiation marker mRNA levels (Fig. 1A). mRNA levels of AnxA2 and AnxA5, similar to hypertrophic marker mRNA levels, were only slightly decreased in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes 8 days after culture, whereas they were similar in AnxA6−/− and wild type cells on days 0, 2, and 4 of culture (Fig. 1A). mRNA levels of proliferative chondrocytes (Sox-9 and type II collagen) were increased in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes compared with wild type cells (Fig. 1B). Although AnxA6−/− chondrocytes looked morphologically similar to wild type chondrocytes in culture (Fig. 2, A–D), APase activity as determined by staining of cultures with the APase substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium (Fig. 2, C and D) or from cell lysates using p-nitrophenyl-phosphate as a substrate (Fig. 2E) was markedly reduced in AnxA6−/− chondrocyte cultures compared with wild type cells. Finally, mineralization was markedly reduced in AnxA6−/− chondrocyte cultures compared with the degree of mineralization in wild type cells (Fig. 2F). These findings demonstrate that mainly terminal differentiation and mineralization events are altered in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes isolated from newborn mice.

FIGURE 1.

mRNA levels of hypertrophic and terminal differentiation markers, AnxA2, and AnxA5 (A) and Sox-9 and type II collagen (B) in wild type (WT) and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes during an 8-day culture period. The mRNA levels of hypertrophic (runx2 and type X collagen (α1(X)) and terminal differentiation (APase, MMP-13, and osteocalcin (OC)), AnxA2, and AnxA5 (A) and Sox-9 and type II collagen (α1(II)) (B) of rib chondrocytes isolated from newborn AnxA6−/− mice and WT littermates after 0, 2, 4, and 8 days (D0, D2, D4, and D8) of treatment with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi were determined by real time PCR and SYBR Green and normalized to 18 S RNA levels. The mRNA levels are expressed relative to the levels of wild type cells at day 0, which were set as 1. Data were obtained from triplicate PCRs using RNA from three different cultures, and values are presented as means ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01 versus WT; b, p < 0.05 versus WT).

FIGURE 2.

APase activity and mineralization of WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes. A and B, phase micrographs of WT (A) and AnxA6−/− (B) chondrocytes cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi for 5 days. Bar, 200 μm. C and D, WT (C) and AnxA6−/− (D) chondrocytes were stained for APase activity after a 5-day culture period. E, APase activity was measured in the lysates of WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes after a 5-day culture period using p-nitrophenyl phosphate and normalized to the total protein concentration. Data were obtained from four different experiments, and values are presented as means ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01 versus WT). F, after an 8-day culture of WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi, cell cultures were stained with alizarin red S to determine the degree of mineralization. To quantify the alizarin red S stain, each dish was incubated with cetylpyridinium chloride for 1 h. The optical density of alizarin red S stain released into solution was measured at 570 nm, normalized to the total amount of protein, and expressed as relative units compared with the optical density per mg of protein of WT cells, which was set as 1. Data were obtained from four different experiments, and values are presented as means ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01 versus WT).

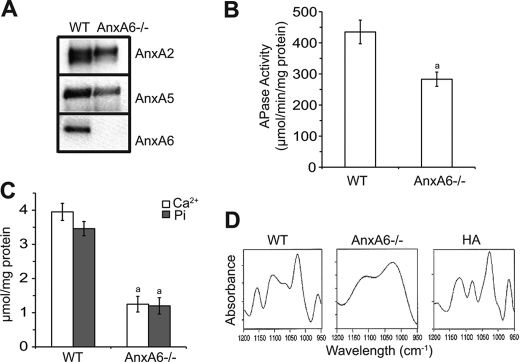

AnxA6 Enables MVs to Initiate Mineralization Process

Previously, we have shown that AnxA6 mediates Ca2+ influx into growth plate chondrocytes and MVs (13, 16). Because mineralization of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes is markedly reduced compared with wild type chondrocytes (Fig. 2F), we determined annexin-mediated Ca2+ influx into MVs and the ability to mineralize in vitro of MVs isolated from AnxA6−/− and wild type chondrocyte cultures as described previously (13). First, we determined the amount of AnxA2 and AnxA5 in AnxA6−/− and wild type MV fractions. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the amounts of AnxA2 and AnxA5 were markedly decreased in AnxA6−/− MVs compared with wild type MVs (Fig. 3A). MVs are enriched in APase activity compared with growth plate chondrocytes (17). Interestingly, APase activity was reduced in AnxA6−/− MVs compared with the activity of wild type MVs (Fig. 3B). In addition, AnxA6−/− MVs showed markedly reduced Ca2+ and Pi content compared with wild type MVs (Fig. 3C). Finally, when incubated in synthetic cartilage lymph, AnxA6−/− MVs were not able to initiate the formation of hydroxyapatite-like crystals after 24-h incubation in synthetic cartilage lymph. Although wild type MVs formed hydroxyapatite-like crystals after 24-h incubation in synthetic cartilage lymph as indicated by FTIR peaks at 960, 1,025, 1,102, 1,065, and 1,157 cm−1 consistent with apatite structure, FTIR spectroscopy of AnxA6−/− MVs exhibited no such peaks but rather a nondescript pattern consistent with lack of a mineral phase (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Isolation and characterization of MVs isolated from WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocyte cultures. MVs were isolated from WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes cultured for 8 days in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi. MVs were isolated from these cultures using enzymatic digestions and ultracentrifugation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, equal amounts of MV proteins (30 μg of total protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for the amounts of AnxA2, AnxA5, and AnxA6 by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for AnxA2, AnxA5, and AnxA6. B, APase activity in MV fractions was determined using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate and normalized to the total amount of protein. C, amounts of Ca2+ and Pi in MV fractions were analyzed using colormetric assays as described under “Experiment Procedures” and normalized to the total amount of protein. B and C, data were obtained from three different vesicle preparations and are expressed as mean ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01 versus WT MVs). D, FTIR spectra of WT and AnxA6−/− MVs. Shown are second derivative spectra of the ν1ν3 phosphate region of WT and AnxA6−/− MVs incubated in synthetic cartilage lymph for 24 h at 37 °C and hydroxyapatite (HA). Note that in WT MVs bands can be seen at 960, 1,025, 1,065, 1,102, and 1,157 cm−1, whereas these bands are absent in AnxA6−/− MVs. Also note the similarity of the spectra of WT MVs and hydroxyapatite.

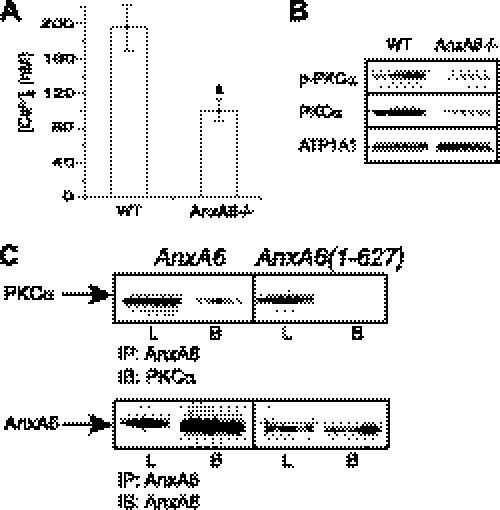

AnxA6 Increases Intracellular Ca2+ and Stimulates PKCα Activity

Next, we determined the mechanisms of how AnxA6 stimulates the terminal differentiation events of chondrocytes. Previously, we have shown that annexin-mediated Ca2+ influx into chondrocytes affects their terminal differentiation (13, 18). In addition, the activation of PKCα requires increases in intracellular Ca2+ and plasma membrane association. PKCα plays an important role in chondrocyte differentiation (19, 20). The measurement of [Ca2+]i in AnxA6−/− and wild type chondrocytes treated for 5 days with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi revealed that the [Ca2+]i of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes was markedly decreased compared with the levels in wild type chondrocytes (Fig. 4A). The findings showing that AnxA6 interacts with active PKCα suggest that AnxA6 may be required for membrane translocation and activation of PKCα (8). Fig. 4B shows that the amount of membrane-associated, phosphorylated, and total PKCα decreased in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes cultured for 1 h in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi compared with the amount of membrane-associated, phosphorylated, and total PKCα in wild type chondrocytes cultured under the same conditions. Previous studies have suggested that the 45 most C-terminal amino acids (amino acids 628–673) are the regions that bind to PKCα (21). We generated a pcDNA expression vector containing AnxA6 cDNA lacking the 45 most C-terminal amino acids (AnxA6(1–627)). We performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments in which total cell extracts from AnxA6−/− chondrocytes transfected with empty expression vector, expression vector containing full-length AnxA6 cDNA, or expression vector containing AnxA6(1–627) were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for AnxA6, and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for PKCα. PKCα co-immunoprecipitated with full-length AnxA6 as shown by the immunoblot of AnxA6 immunoprecipitates of cell extract from AnxA6−/− cells transfected with full-length AnxA6 with antibodies specific for PKCα (Fig. 4C). No PKCα co-immunoprecipitated with AnxA6(1–627) (Fig. 4C). Immunoblotting of the full-length and AnxA6(1–627) immunoprecipitates with antibodies specific for AnxA6 revealed a band for AnxA6 (Fig. 4C). These findings indicate that PKCα activity increases with the levels of AnxA6 expression and that AnxA6-mediated regulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and its binding to PKCα modulate PKCα activity. In addition, our findings show that the C-terminal region of AnxA6 binds to PKCα.

FIGURE 4.

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i, phosphorylated and total PKCα levels in WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes, and co-immunoprecipitation of PKCα with antibodies specific for AnxA6. A, [Ca2+]i of WT and AnxA6−/− rib chondrocytes treated for 5 days with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi was measured using fura-2AM as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data were obtained from three different experiments and are expressed as mean ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01 versus WT chondrocytes). B, the levels of plasma membrane-associated phosphorylated (p-PKCα) and total PKCα in WT chondrocytes and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes treated for 1 h with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi were determined by immunoblotting of plasma membrane fractions using antibodies specific for phosphorylated and total PKCα. ATP1A1 was used as a control to show equal loading. C, AnxA6−/− rib chondrocytes were transfected with empty pcDNA expression vector or pcDNA vector containing full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627). Three days after transfection, total cell extracts were co-immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for AnxA6. The immunoprecipitates (IP) were then analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies specific for total PKCα or AnxA6. L, total cell lysate; B, beads after immunoprecipitation.

Lack of PKCα-dependent Stimulation of ERK and p38 MAPK Signaling Pathway Activities in AnxA6−/− Chondrocytes

Previous studies have shown PKCα-dependent stimulation of ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathway activities. These two MAPK signaling pathways have been shown to stimulate hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes (5, 22). Therefore, we tested whether AnxA6-mediated regulation of PKCα activity affects the ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Before treating chondrocytes with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi, cells were cultured for 24 h in the absence of FCS. Fig. 5A demonstrates that treating wild type chondrocytes with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi showed a prolonged activation of ERK-MAPK signaling as indicated by the increased levels of phosphorylated ERK, especially ERK2, after 30, 60, and 120 min of treatment compared with the levels in AnxA6−/− cells. After 5 min of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi treatment, the intensities of the phosphorylated ERK1/2 bands were similar in wild type and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes (Fig. 5A). Similar to a previous study, which demonstrated that increased phosphorylation of ERK2 primarily stimulates terminal differentiation events (5), our findings show that AnxA6-mediated modulation of ERK activity mainly affects ERK2 phosphorylation. Decreased levels of phosphorylated p38 in cell lysates from AnxA6−/− chondrocytes compared with the levels in cell lysates of wild type chondrocytes cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi were detected at all time points tested (Fig. 5A). Untreated wild type or AnxA6−/− chondrocytes showed very low amounts of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and p38 over the 2-h time period. The amounts did not change during the 2-h time period and were similar to the levels at 0 min (data not shown). PKC(20–28) markedly reduced the levels of phosphorylated ERK and p38 in wild type chondrocytes cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi for 30 min. The reduced levels of phosphorylated ERK and p38 in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes compared with the levels of wild type chondrocytes were not further decreased in the presence of PKC(20–28) (Fig. 5B). These findings show that AnxA6 modulates ERK and p38 activities via its modulatory function on PKCα activity.

FIGURE 5.

ERK and p38 MAPK activities in WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes. Cell lysates from WT chondrocytes or AnxA6−/− chondrocytes cultured in the absence or presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi for different lengths of time (A) or from WT or AnxA6−/− chondrocytes cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi and in the absence (Untreated) or presence of the PKCα-specific inhibitor PKC(20–28) for 1 h (B) were analyzed for ERK and p38 activities by immunoblotting cell lysates (30 μg of total protein) with antibodies specific for p-ERK and total ERK or p-p38 and total p38.

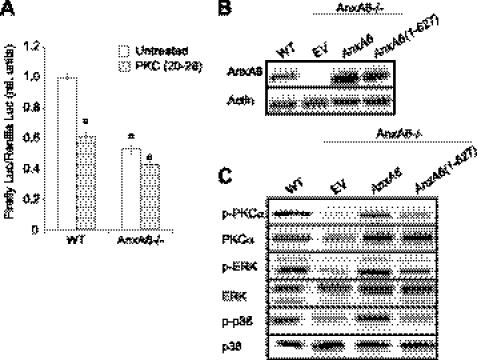

AnxA6-mediated Modulation of PKCα, ERK, and p38 MAPK Activities Stimulates Terminal Differentiation of Chondrocytes

To determine whether AnxA6-mediated stimulation of PKCα activity affects the terminal differentiation of chondrocytes, we treated wild type and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with PKC(20–28) in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi and determined runx2 activity as an indicator of the degree of the terminal differentiation of chondrocytes using the pOSE2 luciferase reporter plasmid. This pOSE2 luciferase reporter plasmid contains six copies of the runx2 DNA binding motif. Luciferase activity from the pOSE2 reporter plasmid was markedly reduced in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes compared with the activity of wild type chondrocytes (Fig. 6A). Treatment of wild type chondrocytes with PKC(20–28) markedly decreased pOSE2 luciferase activity, whereas it did not significantly reduce pOSE2 luciferase activity in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

AnxA6 stimulates runx2 transcription activity via PKCα, and transfection with full-length AnxA6 but not AnxA6(1–627) rescues reduced PKCα, ERK, and p38 activities in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes. A, WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes were transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter construct containing six runx2 DNA-binding elements (pOSE2-Luc) and cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi and in the absence (Untreated) or presence of PKC(20–28). After 48 h, the cells were lysed, and the lysates were analyzed for firefly luciferase (Luc) activity and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity as described under “Experimental Procedures.” rel., relative. Data were obtained from three different experiments and are expressed as mean ± S.D. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (a, p < 0.01 versus untreated WT chondrocytes). B, total cell extracts (30 μg of total protein) from WT chondrocytes and empty expression vector-transfected (EV) and expression vector containing full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627) cDNA-transfected AnxA6−/− chondrocytes treated with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies specific for AnxA6 after 4-day transfection. β-Actin was used as a control to show equal loading. C, cell lysates from WT chondrocytes or AnxA6−/− chondrocytes transfected with empty expression vector (EV), full-length AnxA6, or AnxA6(1–627) cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi for 1 h were analyzed for PKCα, ERK, and p38 activities by immunoblotting cell lysates (30 μg of total protein) with antibodies specific for phosphorylated PKCα (p-PKCα) and total PKCα, p-ERK and total ERK, or p-p38 and total p38.

Next, we performed rescue experiments and transfected AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with pcDNA expression vector containing full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627). As described above, full-length AnxA6 binds to PKCα, whereas AnxA6(1–627) does not bind to PKCα (see Fig. 4C). Transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with pcDNA expression vector containing full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627) resulted in AnxA6 protein levels that were markedly higher than endogenous AnxA6 protein levels in wild type chondrocytes (Fig. 6B). Full-length AnxA6 and AnxA6(1–627) rescued the reduced [Ca2+]i levels in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes (data not shown). Analysis of the levels of phosphorylated PKCα, ERK, and p38 of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes transfected with full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627) revealed that transfection with full-length AnxA6 rescued the reduced levels of phosphorylated PKCα, ERK, and p38 in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes treated for 1 h with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi to levels similar to the levels of wild type cells (Fig. 6C). In contrast, transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with AnxA6(1–627) only slightly increased the levels of phosphorylated PKCα, ERK, and p38 (Fig. 6C). These findings reveal that the binding of AnxA6 to PKCα stimulates its activity and that the AnxA6-mediated stimulation of PKCα activity results in increased levels of phosphorylated ERK and p38.

Next, we determined whether transient transfection with full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627) rescues the decreased mRNA levels of terminal differentiation markers in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes. Because the transient transfection of chondrocytes resulted in the increased expression of AnxA6 for only about 4–5 days, we analyzed the mRNA levels of terminal differentiation markers, including APase, MMP-13, osteocalcin, and runx2, 4 days after the transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes and treatment with ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi. Transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with full-length AnxA6 rescued the decreased levels of the terminal differentiation marker mRNA levels. mRNA levels of the terminal differentiation markers in full-length AnxA6-transfected AnxA6−/− chondrocytes were higher than the levels in wild type cells because the transfection of AnxA6−/− cells with full-length AnxA6 or AnxA6(1–627) resulted in higher AnxA6 protein levels than the endogenous AnxA6 protein levels in wild type cells (see Fig. 6B). In contrast, transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with AnxA6(1–627) increased the mRNA levels of APase, MMP-13, and runx2 to a much lesser degree than transfection with full-length AnxA6. The osteocalcin mRNA levels did not change after transfection with AnxA6(1–627) compared with empty vector-transfected AnxA6−/− cells (Fig. 7). These findings reveal that the transfection of full-length AnxA6 fully rescued the decreased mRNA levels of terminal differentiation markers in AnxaA6−/− chondrocytes, whereas the transfection with AnxA6(1–627), which does not stimulate PKCα activity, does not fully rescue the decreased mRNA levels of terminal differentiation markers.

FIGURE 7.

Full-length AnxA6 but not AnxA6(1–627) rescues mRNA levels of APase, MMP-13, osteocalcin, and runx2. WT and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes transfected with empty expression vector (EV) or expression vector containing full-length AnxA6 cDNA or AnxA6(1–627) cDNA were cultured for 4 days in the presence of ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi. APase, MMP-13, osteocalcin (OC), and runx2 mRNA levels of WT chondrocytes and AnxA6−/− chondrocytes transfected with the various expression vector constructs were detected by quantitative real time PCR using SYBR Green. Data were obtained from triplicate PCRs using RNA from three different cultures, and data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01 versus WT chondrocytes; b, p < 0.01 versus empty expression vector-transfected AnxA6−/− chondrocytes; c, p < 0.01 versus full-length AnxA6 expression vector-transfected AnxA6−/− chondrocytes).

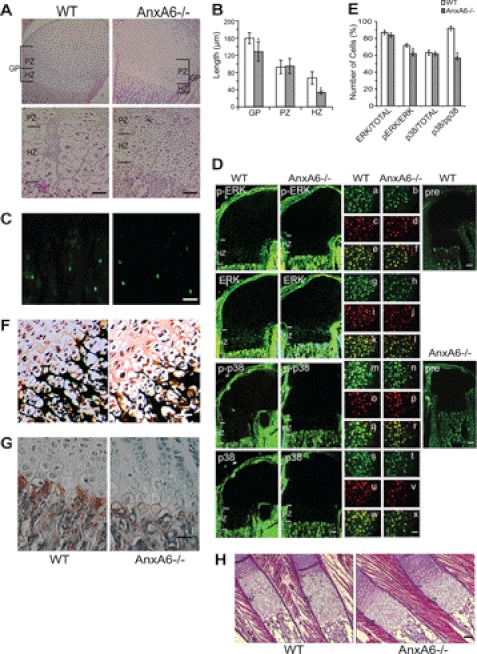

In Vivo Consequences of Loss of AnxA6

Finally, we analyzed the skeletal phenotype of newborn AnxA6−/− mice. Histomorphometric analysis of the femoral and tibial growth plates revealed that the mean growth plate length (proliferative and hypertrophic zones) was ∼25% less in the AnxA6−/− mice than in that of wild type littermates (n = 10; Fig. 8, A and B). Although the mean length of the proliferative zones was similar, the mean length of hypertrophic zones was reduced in AnxA6−/− mice (Fig. 8, A and B). The number of hypertrophic chondrocytes was significantly reduced in AnxA6−/− growth plates compared with the number of hypertrophic cells in wild type growth plates (156 ± 6 hypertrophic chondrocytes in WT growth plates versus 96 ± 5 hypertrophic chondrocytes in AnxA6−/− growth plates; n = 5; p < 0.01). TUNEL labeling revealed a similar number of TUNEL-positive growth plate chondrocytes in the growth plates from newborn AnxA6−/− and wild type mice (Fig. 8C). Immunofluorescence staining with antibodies specific for the phosphorylated forms of ERK and p38 revealed a reduced number of immunopositive growth plate chondrocytes for phosphorylated ERK or p38 per number of immunopositive cells for total ERK or p38 in the hypertrophic zone of the growth plate from AnxA6−/− newborn mice compared with the number of immunopositive cells in the hypertrophic zone of the wild type growth plate (Fig. 8, D and E). The number of phosphorylated p38-immunopositive chondrocytes was notably more reduced than the number of phosphorylated ERK-immunopositive chondrocytes in AnxA6−/− growth plates (Fig. 8, D and E). The number of immunopositive growth plate chondrocytes for total ERK or total p38 per total number of cells in the hypertrophic zone of the AnxA6−/− growth plate was similar to the number of immunopositive cells in the hypertrophic zone of the wild type growth plate (Fig. 8, D and E). These findings reveal that ERK and p38 MAPK activities are decreased in vivo in the hypertrophic zone of the AnxA6−/− growth plate. The degree of mineralization of growth plate cartilage was reduced in newborn AnxA6−/− mice compared with the degree of mineralization in wild type growth plates as indicated by von Kossa staining (Fig. 8F). Furthermore, immunostaining for APase, a marker for terminally differentiated growth plate chondrocytes, was reduced in AnxA6−/− mice compared with wild type littermates (Fig. 8G). Similar to the femoral and tibial growth plates, the length of the hypertrophic zone of the growth plates in ribs isolated from newborn AnxA6−/− mice was notably shorter than the hypertrophic zone of wild type rib growth plates (Fig. 8H).

FIGURE 8.

Histological and histomorphometric analyses; evaluation of hypertrophic chondrocyte apoptosis and mineralization; and immunohistochemical analysis of APase, phosphorylated and total ERK, and p38 of the femoral epiphyseal and rib growth plate of newborn AnxA6−/− mice and WT littermates. A, hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the femoral epiphyseal growth plate of a newborn AnxA6−/− mouse and WT littermate. Bar, 100 μm. B, histomorphometric analysis of the length of the total growth plate (GP), the proliferative zone (PZ), and the hypertrophic zone (HZ) of 10 newborn AnxA6−/− mice and 10 WT littermates. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. (a, p < 0.01; b, p < 0.05 versus WT). C, TUNEL labeling of hypertrophic chondrocytes in the femoral epiphyseal growth plate of a newborn AnxA6−/− mouse and WT littermate. Bar, 100 μm. D, immunohistochemical analysis of femoral epiphyseal AnxA6−/− and WT growth plates was performed using antibodies against p-ERK and p-p38 MAPK and antibody against total ERK and p38 protein, respectively. In addition, immunostaining with non-immune IgG (pre) was performed as negative control staining. Bar, 100 μm. Panels a, c, e, g, i, k, m, o, q, s, u, and w, higher magnification of chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone of WT growth plates immunostained with antibodies specific for p-ERK (panel a), total ERK (panel g), p-p38 (panel m), and total p38 (panel s) and counterstained with DAPI (panels c, i, o, and u). Merged images of p-ERK antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel e), total ERK antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel k), p-p38 antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel q), and total p38 antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel w) are shown. Panels b, d, f, h, j, l, n, p, r, t, v, and x, higher magnification of chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone of AnxA6−/− growth plates immunostained with antibodies specific for p-ERK (panel b), total ERK (panel h), p-p38 (panel n), and total p38 (panel t) and counterstained with DAPI (panels d, j, p, and v). Merged images of p-ERK antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel f), total ERK antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel l), p-p38 antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel r), and total p38 antibody- and DAPI-stained images (panel x) are shown. Bar, 100 μm. E, the number of total cells (DAPI-positive cells), cells immunopositive for total ERK or p38, and cells immunopositive for p-ERK or p-p38 in the hypertrophic zone of femoral epiphyseal AnxA6−/− and WT growth plates (n = 3) was counted and expressed as a percentage of total ERK- or p38-immunopositive cells per total cells, p-ERK-immunopositive cells per total ERK-immunopositive cells, or p-p38-immunopositive cells per total p38-immunopositive cells. F, von Kossa stained sections of the femoral epiphyseal growth plate of a newborn AnxA6−/− mouse and WT littermate. Bar, 100 μm. G, immunostaining of sections of the femoral epiphyseal growth plate of a newborn AnxA6−/− mouse and WT littermate with antibodies specific for APase. Bar, 100 μm. H, hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of the rib growth plates of a newborn AnxA6−/− mouse and WT littermate. Bar, 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that AnxA6 regulates the terminal differentiation and mineralization events of newborn growth plate chondrocytes. Our in vitro and in vivo findings indicate that AnxA6 does not delay the differentiation of chondrocytes to hypertrophic cells but the further terminal differentiation of hypertrophic chondrocytes. AnxA6−/− growth plate chondrocytes, however, appear to undergo apoptosis at a rate similar to that of terminal differentiated wild type growth plate chondrocytes despite their delayed terminal differentiation. Consequently, the hypertrophic zone of newborn AnxA6−/− growth plates is smaller than the hypertrophic zone of newborn wild type growth plates.

Our findings show that AnxA6 affects intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and directly interacts with PKCα. The interaction between AnxA6 and PKCα stimulates the activity of PKCα. In addition, we provide evidence that the last 45 amino acids of AnxA6 are required for binding to PKCα. Our findings confirm a previous study showing a direct protein-protein interaction between AnxA6 and PKCα (8). Our findings showing that although the transfection of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes with full-length AnxA6 completely rescued delayed terminal differentiation transfection with AnxA6(1–627), which has lost the ability to bind to PKCα, only partially rescued the delayed terminal differentiation demonstrate the importance of the interaction between AnxA6 and PKCα and the AnxA6-mediated stimulation of PKCα activity in the terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes.

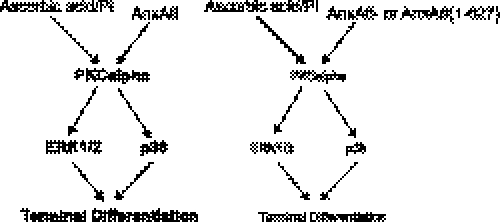

Previous studies from our and other laboratories have shown that ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi stimulated hypertrophic, terminal, and mineralization events of growth plate and sternal chondrocytes (11, 15). Other studies showed that extracellular Pi is transported back into chondrocytes via the Na+/Pi co-transporter where it acts as a signaling molecule that activates various signaling pathways, including the ERK-MAPK signaling pathway (23). In this study, we show that ascorbic acid and additional 1.5 mm Pi activate PKCα and ultimately ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. The AnxA6/PKCα interaction results in the further stimulation of PKCα activity. PKCα activation by ascorbic acid, 1.5 mm Pi, and AnxA6 is the main upstream event that then leads to the modulation of ERK and p38 MAPK activities (Fig. 9). PKCα has been shown to be involved in the activation of MAPK signaling pathways (24, 25). More importantly, a previous study has demonstrated that CHO cells, which express AnxA6, activate MAPK signaling pathways in a PKCα-dependent manner, whereas CHO cells that do not express AnxA6 activate MAPK signaling pathways in a PKCα-independent manner (7, 8). ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways have been recently shown to play important roles in hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events (5, 22, 26). For example, Zhen et al. (22) showed that the steady-state levels of activated p38 MAPK increase markedly during the maturation of growth plate chondrocytes and that hypertrophic chondrocytes displayed about 10-fold higher phosphorylated p38 levels than prehypertrophic chondrocytes with no differences in total p38 content. Furthermore, a previous study showed that ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways play major roles in the regulation of hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes (5). In addition, both pathways have been shown to affect runx2 expression and transcription activity (27–29). Runx2 is a major transcription factor regulating the hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes (30). Therefore, it is plausible that the modulation of ERK and p38 MAPK activities as a downstream event of AnxA6-mediated PKCα activation plays a major role in the stimulatory effect of AnxA6 on the terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes.

FIGURE 9.

Scheme depicting possible role of AnxA6 in modulating (stimulating) ERK and p38 activities through direct binding of AnxA6 to PKCα and stimulating PKCα activity. Ascorbic acid and extracellular Pi activate PKCα and ultimately ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. The AnxA6/PKCα interaction results in further stimulation of PKCα activity, increased ERK and p38 activity, and ultimately enhanced terminal differentiation events of chondrocytes. Lack of AnxA6 function (AnxA6−) or a truncated AnxA6 (AnxA6(1–627)), which has lost its ability to bind to PKCα, results in reduced activation of PKCα, ERK, and p38 and consequently leads to delayed terminal differentiation of chondrocytes treated with ascorbic acid and extracellular Pi.

Because we only show increased and sustained phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in total cell extracts but not the degree of nuclear translocation of phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) and phosphorylated p38 (p-p38) in the presence of AnxA6, we cannot conclude whether increased and sustained phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in the presence of AnxA6 regulates the expression of terminal differentiation marker genes in chondrocytes directly or indirectly by affecting the activities of other signaling pathways. A previous study has demonstrated that phosphorylation of ERK is necessary, but not sufficient, for nuclear translocation of ERK. In addition, nuclear translocation requires the association of ERK with partner proteins via the common docking motif (31). Activated (phosphorylated) cytoplasmic ERK and p38 have been shown to phosphorylate linker regions of Smads, the main downstream transcription factors of transforming growth factor (TGF) β and bone morphogenetic protein signaling, and runx2, thereby regulating the transcription activities of these Smads and runx2 (32, 33). TGFβ- and bone morphogenetic protein-mediated Smad signaling and runx2 transcription activity play major roles in chondrocyte terminal differentiation (5, 30). Therefore, the AnxA6-mediated increased and sustained phosphorylation of ERK and p38 after treatment with ascorbic acid and additional Pi may affect terminal marker gene expression and terminal chondrocyte differentiation directly or indirectly via the regulation of the activities of other signaling pathways.

Later in postnatal development, the size of the hypertrophic zone of AnxA6−/− growth plates catches up with the size of the hypertrophic zone of wild type growth plates (data not shown). This finding demonstrates that AnxA6 accelerates terminal differentiation events but does not initiate these events during late embryonic and early postnatal development. It is possible that later in postnatal development signaling pathways other than the MAPK signaling pathways play important roles in the regulation of hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events of growth plate chondrocytes or that factors that used the MAPK signaling pathways in embryonic and early postnatal development use other signaling pathways later in postnatal development to control hypertrophic and terminal differentiation events. This hypothesis is supported by recent findings showing that fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling via FGF receptor 3 regulates growth plate chondrocyte proliferation in opposite ways at different stages of development. During embryonic and early postnatal stages, FGF signaling stimulates chondrocyte proliferation via MAPK signaling, whereas during later postnatal stages, FGF signaling inhibits chondrocyte proliferation via signaling through STAT proteins (34).

Besides AnxA6, AnxA2 and AnxA5 are also highly expressed in hypertrophic growth plate cartilage (3, 35). Many of the functions of annexins are common to several members of the family, whereas some functions are specific for a particular member. Besides the binding of Ca2+ and the interaction with lipids in the presence of Ca2+, AnxA2, AnxA5, and AnxA6 also have in common that all three annexins mediate Ca2+ influx across membranes (1, 16). However, the interactions with PKCα and the resulting modulation of MAPK activities have been reported only for AnxA6, not for AnxA2 or AnxA5 (7, 8). This may explain the absence of a phenotype in AnxA5 knock-out mice, whereas we report in this study delayed terminal differentiation of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes (36). In addition, our findings showing reduced AnxA2 and AnxA5 protein amounts in AnxA6−/− MVs despite a lack of change of AnxA2 and AnxA5 gene expression levels in AnxA6−/− chondrocytes suggest that AnxA6 may also play a role in the assembly of proteins to specialized plasma membrane regions from which MVs will eventually be released. Previous studies have shown that annexins play a major role in the formation of specialized plasma membrane regions (lipid rafts) and the assembly of proteins to these raft regions (37). However, the question remains regarding the lack of growth plate phenotype in newborn AnxA5/AnxA6 double knock-out mice reported by Belluoccio et al. (38). One possible explanation is that AnxA5 and AnxA6 may play opposing rather than redundant roles in chondrocyte terminal differentiation and apoptosis. This hypothesis is supported by our current and previous findings and by previous findings from other laboratories showing that the binding of AnxA6 to PKCα stimulates ERK and p38 MAPK activities, whereas the binding of AnxA5 to PKCα inhibits PKCα activity, resulting in the apoptosis of chondrocytes and other cell types, and would explain the different phenotypes in AnxA6 knock-out and AnxA5/AnxA6 double knock-out mice (7, 39–41). The lack of AnxA6 results in a decreased size of the hypertrophic zone in growth plates from newborn mice most likely because of the delayed terminal differentiation events but a similar apoptosis rate in AnxA6−/− compared with wild type growth plates, whereas a decreased rate of terminal differentiation and a decreased rate of apoptosis in AnxA5/AnxA6 double knock-out mice may result in a similarly sized hypertrophic zone as in wild type mice. A detailed analysis of terminal differentiation and apoptotic events in these various annexin knock-out mice and wild type littermates needs to be performed to determine the reason for the different skeletal phenotypes of AnxA6 knock-out and AnxA5/AnxA6 double knock-out mice.

The similar apoptosis rate of growth plate chondrocytes in newborn AnxA6−/− and wild type growth plates suggests that AnxA6−/− growth plate chondrocytes undergo apoptosis at the chondro-osseous junction even though these cells have not reached their final terminal differentiation stage. In addition, these findings suggest that the regulation of growth plate chondrocyte apoptosis may depend on chondrocyte hypertrophy as suggested in a previous study but not on the stage of hypertrophy or terminal differentiation (23). The apoptosis of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes despite their delayed terminal differentiation rate may result from increased AnxA5 interactions with PKCα in the absence of AnxA6. We have previously shown that AnxA5/PKCα interactions cause apoptosis of growth plate chondrocytes regardless of their stage of terminal differentiation (41). A recent study has shown that phosphate-induced apoptosis was dependent on ERK phosphorylation (23). The number of immunopositive growth plate chondrocytes for phosphorylated ERK was reduced in the hypertrophic zone of AnxA6−/− growth plates. However, the reduced ERK phosphorylation in the hypertrophic zone of AnxA6−/− growth plates was not sufficient to result in reduced apoptosis of AnxA6−/− chondrocytes.

The cellular response to a signaling pathway is dependent on the activation of the signaling pathway as well as the degree of activation and the time period of activation. Our results show that AnxA6 does not activate PKCα and ultimately ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways but rather acts as an intracellular modulator of the degree and length of activation of these pathways. The intracellular modulation of signaling pathways may also play an important role during disease pathology. For example, increased expression of annexin A1 in breast cancer cells results in the constitutive activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB. Constitute activation of NF-κB in breast cancer cells results in tumor migration and metastasis (42). Interestingly, AnxA6 is not expressed in healthy human articular cartilage but is expressed in osteoarthritic cartilage (3). Therefore, it is plausible that increased expression of AnxA6 in osteoarthritic cartilage via intracellular modulation of signaling pathways may contribute to osteoarthritis pathology.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that AnxA6 regulates the terminal differentiation and mineralization events of chondrocytes by modulating Ca2+ homeostasis in chondrocytes and MVs and ERK and p38 MAPK activities via interactions of AnxA6 with PKCα. In addition, the modulation of signaling pathway activities by AnxA6 may present an explanation for the fact that the same growth factor may act anabolically as well as catabolically on articular cartilage depending on the expression levels of AnxA6.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AR046245 and R01AR049074 from the NIAMS (to T. K.). This work was also supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (to S. E. M.).

- AnxA6

- annexin A6

- AnxA6−/−

- annexin A6 knockout

- APase

- alkaline phosphatase

- [Ca2+]i

- intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- MMP-13

- matrix metalloproteinase-13

- MV

- matrix vesicle

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- PKC(20–28)

- myristoylated protein kinase C inhibitor 20–28

- bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- p-ERK

- phosphorylated ERK

- p-p38

- phosphorylated p38.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gerke V., Moss S. E. (2002) Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 82, 331–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Geisow M. J., Walker J. H., Boustead C., Taylor W. (1988) in Molecular Mechanisms in Secretion (Thorn N. A., Traiman M., Peterson O. H., eds) pp. 598–608, Munksgaard, Copenhagen [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pfander D., Swoboda B., Kirsch T. (2001) Expression of early and late differentiation markers (proliferating cell nuclear antigen, syndecan-3, annexin VI, and alkaline phosphatase) by human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 159, 1777–1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lefebvre V., Smits P. (2005) Transcriptional control of chondrocyte fate and differentiation. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 75, 200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shimo T., Koyama E., Sugito H., Wu C., Shimo S., Pacifici M. (2005) Retinoid signaling regulates CTGF expression in hypertrophic chondrocytes with differential involvement of MAP kinases. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 867–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grewal T., Evans R., Rentero C., Tebar F., Cubells L., de Diego I., Kirchhoff M. F., Hughes W. E., Heeren J., Rye K. A., Rinninger F., Daly R. J., Pol A., Enrich C. (2005) Annexin A6 stimulates the membrane recruitment of p120GAP to modulate Ras and Raf-1 activity. Oncogene 24, 5809–5820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rentero C., Evans R., Wood P., Tebar F., Vilà de Muga S., Cubells L., de Diego I., Hayes T. E., Hughes W. E., Pol A., Rye K. A., Enrich C., Grewal T. (2006) Inhibition of H-Ras and MAPK is compensated by PKC-dependent pathways in annexin A6 expressing cells. Cell. Signal. 18, 1006–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmitz-Peiffer C., Browne C. L., Walker J. H., Biden T. J. (1998) Activated protein kinase C α associates with annexin VI from skeletal muscle. Biochem. J. 330, 675–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hawkins T. E., Roes J., Rees D., Monkhouse J., Moss S. E. (1999) Immunological development and cardiovascular function are normal in annexin VI null mutant mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8028–8032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lefebvre V., Garofalo S., Zhou G., Metsäranta M., Vuorio E., De Crombrugghe B. (1994) Characterization of primary cultures of chondrocytes from type II collagen/β-galactosidase transgenic mice. Matrix Biol. 14, 329–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kirsch T., Nah H. D., Shapiro I. M., Pacifici M. (1997) Regulated production of mineralization-competent matrix vesicles in hypertrophic chondrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 137, 1149–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kirsch T., Swoboda B., von der Mark K. (1992) Ascorbate independent differentiation of human chondrocytes in vitro: simultaneous expression of types I and X collagen and matrix mineralization. Differentiation 52, 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang W., Kirsch T. (2002) Retinoic acid stimulates annexin-mediated growth plate chondrocyte mineralization. J. Cell Biol. 157, 1061–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirsch T., Wuthier R. E. (1994) Stimulation of calcification of growth plate cartilage matrix vesicles by binding to type II and X collagens. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 11462–11469 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leboy P. S., Vaias L., Uschmann B., Golub E., Adams S. L., Pacifici M. (1989) Ascorbic acid induces alkaline phosphatase, type X collagen, and calcium deposition in cultured chick chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 17281–17286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirsch T., Harrison G., Golub E. E., Nah H. D. (2000) The roles of annexins and types II and X collagen in matrix vesicle-mediated mineralization of growth plate cartilage. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35577–35583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anderson H. C. (2003) Matrix vesicles and calcification. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 5, 222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang W., Xu J., Kirsch T. (2003) Annexin-mediated Ca2+ influx regulates growth plate chondrocyte maturation and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3762–3769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyan B. D., Schwartz Z. (2004) Rapid vitamin D-dependent PKC signaling shares features with estrogen-dependent PKC signaling in cartilage and bone. Steroids 69, 591–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nakashima S. (2002) Protein kinase C α (PKCα): regulation and biological function. J. Biochem. 132, 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubois T., Oudinet J. P., Mira J. P., Russo-Marie F. (1996) Annexins and protein kinases C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1313, 290–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhen X., Wei L., Wu Q., Zhang Y., Chen Q. (2001) Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 mediates regulation of chondrocyte differentiation by parathyroid hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4879–4885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miedlich S. U., Zalutskaya A., Zhu E. D., Demay M. B. (2010) Phosphate-induced apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes is associated with a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and is dependent upon Erk1/2 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18270–18275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsieh Y. H., Wu T. T., Huang C. Y., Hsieh Y. S., Hwang J. M., Liu J. Y. (2007) p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in protein kinase Cα-regulated invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 67, 4320–4327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Young S. W., Dickens M., Tavaré J. M. (1996) Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by protein kinase C isotypes α, β I and γ, but not ϵ. FEBS Lett. 384, 181–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Namdari S., Wei L., Moore D., Chen Q. (2008) Reduced limb length and worsened osteoarthritis in adult mice after genetic inhibition of p38 MAP kinase activity in cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 3520–3529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ge C., Xiao G., Jiang D., Franceschi R. T. (2007) Critical role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-MAPK pathway in osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development. J. Cell Biol. 176, 709–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenblatt M. B., Shim J. H., Zou W., Sitara D., Schweitzer M., Hu D., Lotinun S., Sano Y., Baron R., Park J. M., Arthur S., Xie M., Schneider M. D., Zhai B., Gygi S., Davis R., Glimcher L. H. (2010) The p38 MAPK pathway is essential for skeletogenesis and bone homeostasis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 120, 2457–2473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xiao G., Jiang D., Thomas P., Benson M. D., Guan K., Karsenty G., Franceschi R. T. (2000) MAPK pathways activate and phosphorylate the osteoblast-specific transcription factor, cbfa1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4453–4459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Takeda S., Bonnamy J. P., Owen M. J., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (2001) Continuous expression of Cbfa1 in nonhypertrophic chondrocytes uncovers its ability to induce hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation and partially rescues Cbfa1-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 15, 467–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Caunt C. J., McArdle C. A. (2012) ERK phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation: insights from single-cell imaging. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wrighton K. H., Lin X., Feng X. H. (2009) Phospho-control of TGF-β superfamily signaling. Cell Res. 19, 8–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ge C., Yang Q., Zhao G., Yu H., Kirkwood K. L., Franceschi R. T. (2012) Interactions between extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 map kinase pathways in the control of RUNX2 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 538–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iwata T., Chen L., Li C., Ovchinnikov D. A., Behringer R. R., Francomano C. A., Deng C. X. (2000) A neonatal lethal mutation in FGFR3 uncouples proliferation and differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes in embryos. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 1603–1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kirsch T., Swoboda B., Nah H. (2000) Activation of annexin II and V expression, terminal differentiation, mineralization and apoptosis in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 8, 294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brachvogel B., Dikschas J., Moch H., Welzel H., von der Mark K., Hofmann C., Pöschl E. (2003) Annexin A5 is not essential for skeletal development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2907–2913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Babiychuk E. B., Draeger A. (2000) Annexins in cell membrane dynamics. Ca2+-regulated association of lipid microdomains. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1113–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Belluoccio D., Grskovic I., Niehoff A., Schlötzer-Schrehardt U., Rosenbaum S., Etich J., Frie C., Pausch F., Moss S. E., Pöschl E., Bateman J. F., Brachvogel B. (2010) Deficiency of annexins A5 and A6 induces complex changes in the transcriptome of growth plate cartilage but does not inhibit the induction of mineralization. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cardó-Vila M., Arap W., Pasqualini R. (2003) αVβ5 integrin-dependent programmed cell death triggered by a peptide mimic of annexin V. Mol. Cell 11, 1151–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schlaepfer D. D., Jones J., Haigler H. T. (1992) Inhibition of protein kinase C by annexin V. Biochemistry 31, 1886–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang W., Kirsch T. (2006) Annexin V/β5 integrin interactions regulate apoptosis of growth plate chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30848–30856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bist P., Leow S. C., Phua Q. H., Shu S., Zhuang Q., Loh W. T., Nguyen T. H., Zhou J. B., Hooi S. C., Lim L. H. (2011) Annexin-1 interacts with NEMO and RIP1 to constitutively activate IKK complex and NF-κB: implication in breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene 30, 3174–3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]