Background: Cone snail venoms are a rich source of novel peptide toxins.

Results: Conus imperialis contains two new toxins that define a new cysteine framework and adopt an uncommon all-helical structure.

Conclusion: im23a is a novel conotoxin with respect to amino acid sequence, cysteine framework, and three-dimensional structure.

Significance: These new toxins extend the repertoire of novel peptides derived from cone snails.

Keywords: Disulfide, NMR, Peptides, Protein Structure, Recombinant Protein Expression, Conotoxin, Cysteine Framework, Superfamily

Abstract

Cone snail venoms are a rich source of peptides, many of which are potent and selective modulators of ion channels and receptors. Here we report the isolation and characterization of two novel conotoxins from the venom of Conus imperialis. These two toxins contain a novel cysteine framework, C-C-C-CC-C, which has not been found in other conotoxins described to date. We name it framework XXIII and designate the two toxins im23a and im23b; cDNAs of these toxins exhibit a novel signal peptide sequence, which defines a new K-superfamily. The disulfide connectivity of im23a has been mapped by chemical mapping of partially reduced intermediates and by NMR structure calculations, both of which establish a I-II, III-IV, V-VI pattern of disulfide bridges. This pattern was also confirmed by synthesis of im23a with orthogonal protection of individual cysteine residues. The solution structure of im23a reveals that im23a adopts a novel helical hairpin fold. A cluster of acidic residues on the surface of the molecule is able to bind calcium. The biological activity of the native and recombinant peptides was tested by injection into mice intracranially and intravenously to assess the effects on the central and peripheral nervous systems, respectively. Intracranial injection of im23a or im23b into mice induced excitatory symptoms; however, the biological target of these new toxins has yet to be identified.

Introduction

With more than 700 different species and several hundred or more different toxins in the venom of each, the genus Conus represents a rich source of biologically active peptides, many of which are potent and selective blockers of their target ion channels and receptors (1, 2). In addition to being valuable probes to study specific subtypes of ion channels and receptors (3, 4), conotoxins also serve as promising drug leads for the treatment of various conditions (5–7), and one is already approved for the treatment of chronic pain (8).

Conotoxins are classified into families according to their gene superfamilies, cysteine framework, and molecular targets (1, 2, 9). Typically, the conotoxin precursor signal sequence is highly conserved within a superfamily, and within each superfamily conotoxins are further classified based on the number and arrangement of cysteine residues in the mature conotoxin as well as their disulfide bonding pattern. The conotoxins are subsequently categorized into different families according to their pharmacological target. To date, numerous families have already been characterized, yet many more remain undiscovered.

In this work we identify and characterize two new toxins, im23a and im23b, from venom of the worm-hunting species Conus imperialis. Im23a was expressed recombinantly, and its solution structure and biological activity in mice were determined. Im23a adopts a novel helical hairpin fold with an unexpected disulfide framework. It induced excitatory symptoms when injected intracranially in mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Conotoxin Extraction and Purification

Specimens were collected from the South China Sea and stored at −70 °C. The venom ducts from seven specimens of C. imperialis were dissected, cut into segments, and extracted sequentially with 20 ml of 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) with 0, 20, 40, and 60% acetonitrile in H2O, each for 30 min at 4 °C. The crude extracts were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, then supernatants were pooled, lyophilized, and stored at −70 °C until use.

The crude venom was dissolved in 30% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA and fractionated on a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 size exclusion column (10 × 300 mm, GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with monitoring at 214 nm. The fraction containing im23a and im23b was purified further on a PepmapTM C18 reverse-phase analytical column (250 × 4.6 mm, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min with a gradient of 0–40% Buffer B over 5–90 min. Buffer A is 0.1% TFA, and Buffer B is 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile.

Mass Spectrometry

The molecular masses of the native conotoxins as well as all derivative peptides were analyzed with an API 2000 Q-trap mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). The mass spectrometer, equipped with Turbo Ion Spray Source, was operated in positive ionization mode.

Peptide Alkylation and Edman Sequencing

Purified im23a and im23b were reduced with 50 mm DTT in 20 mm Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm EDTA for 1 h at 37 °C, then alkylated with 0.1 m iodoacetylamide in 20 mm Tris HCl, pH 8.0, in the dark for 1 h at room temperature. The carboxyamidomethyl peptides were sequenced on a Procise 491 protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

cDNA Cloning

The cDNA sequences of im23a and im23b were obtained using 3′- and 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends methods. The total RNAs were prepared using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, around 5 μg of total RNA was used to generate the first strand cDNAs using Superscript II reverse transcriptase with a universal oligo(dT)-containing adapter primer (5′-GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC(dT)17-3′). A gene-specific degenerate sense primer 1 (5′-ATHCCNTAYTGYGGNCARAC-3′; H is A, T, or C; N is A, T, C, or G; Y is C or T; R is A or G) corresponding to the N-terminal seven amino acid residues, IPYCGQT, was used together with an abridged universal amplification primer to amplify the 3′-end cDNA sequences of im23a and im23b. PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T-Easy vector (Promega). Positive clones were selected for sequencing.

5′-Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was performed based on the partial cDNA sequences obtained with 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends. The antisense gene-specific primers 2 and 3 were used sequentially with an abridged anchor primer to amplify the 5′-partial cDNA. Partial sequences of 3′- and 5′- RACE results were overlapped to generate the full-length cDNA sequences of im23a and im23b.

To clone homologous sequences from other species, a gene-specific primer 4 corresponding to the N-terminal sequence of the signal peptide was used together with abridged universal amplification primer to undertake PCR from cDNAs of seven Conus species, C. virgo, C. quercinus, C. leopardus, C. tessulatus, C. bettulatus, C. marmoreus, and C. textile.

Recombinant Expression of im23a and 15N-Labeled im23a

The coding sequence of im23a was inserted into the pGEX-4T-1 vector for recombinant expression in BL21 Rosetta (DE3) cells. After purification with glutathione resin (GE Healthcare), the GST fusion protein was cleaved with thrombin. The recombinant im23a was purified on a Zobax C18 semi-preparative column (Agilent Technologies). As two residues, Gly-Ser, remain at the N terminus of the recombinant im23a after removal of GST, the recombinant product was named GS-im23a. The molecular mass of GS-im23a was determined with mass spectrometry. To produce 15N-labeled im23a for NMR experiments, im23a was expressed in M9 minimum medium with 15NH4Cl (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) and purified as described above.

Aminopeptidase Digestion of Recombinant im23a and Co-elution with Native im23a

Around 200 μg of GS-im23a was dissolved in 100 μl of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.45, and treated with 1 μl of Aeromonas aminopeptidase (0.33 units/μl, Sigma) to remove the Gly-Ser residues at the N terminus of GS-im23a. The im23a product, devoid of any fused residues, was purified on an analytical Pepmap C18 column, and its molecular mass was confirmed with mass spectrometry. This aminopeptidase-treated recombinant im23a was used in a RP-HPLC5 co-elution test with native im23a.

Disulfide Connectivity

The disulfide connectivity of im23a was determined using the partial reduction and alkylation method. Briefly, around 100 μg of GS-im23a in Buffer A was mixed with an equal volume of 20 mm Tris-(carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (Sigma) in 0.17 m citrate buffer at pH 3.0, incubated at 42 °C for 20 min, then applied immediately on a PepmapTM C18 analytical column to separate partially reduced intermediates with a linear gradient of 10–40% Buffer B in 30 min. Around 10 mg of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, Sigma) was added directly into the HPLC fractions to alkylate the partially reduced intermediates for 2 h in the dark. NEM-labeled intermediates were purified on HPLC, checked with mass spectrometry, and then sequenced on an ABI Procise 491 sequencer. The position of NEM-Cys was taken to define the disulfide connectivity of im23a.

Total Synthesis of im23a Using Selective Oxidation Strategy

To further verify the disulfide linkages of im23a, the sequence of recombinant im23a, with Gly-Ser at the N terminus, was synthesized chemically. Details of the synthesis and characterization of this product are included in the supplemental data.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra of 15N-labeled recombinant GS-im23a were recorded at 20 °C on Bruker Avance 500 (equipped with a TXI-cryoprobe), DRX-600, and Avance 800 spectrometers. NMR spectra were processed using TOPSPIN (Version 1.3, Bruker Biospin) and analyzed with XEASY (Version 1.3.13) (10). Spectra were referenced to dioxane at 3.75 ppm. 1H,15N HSQC spectra were collected on 1 mm, 0.3 mm, and 128 μm samples of GS-im23a at 20 °C and 35 °C. At 128 μm, 1H,15N HSQC spectra were also collected over the temperature range 5–25 °C at 5 °C intervals. Backbone resonance assignments were determined by analyzing two-dimensional homonuclear total correlation (TOCSY) and nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOESY) spectra as well as three-dimensional 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC experiments (11). TOCSY and NOESY spectra were also collected at 5 °C to confirm assignments in cases of peak overlap. Final distance restraints for structure calculation were obtained from two-dimensional NOESY spectra acquired on the 800-MHz spectrometer at 128 μm, pH 5.6, and 20 °C. Amide exchange rates were monitored by dissolving freeze-dried material in 10 mm deuterated sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.6 then recording a series of 1H,15N HSQC experiments at 15-min intervals followed by a two-dimensional NOESY experiment at 20 °C once all amide peaks had exchanged completely. TOCSY and NOESY spectra were also recorded on a 128 μm solution of unlabeled recombinant GS-im23a, pH 5.6, at 20 °C. One-dimensional spectra of synthetic im23a (128 μm, pH 5.6) were collected at 20 °C. The effect of Ca2+ binding was determined by recording 1H,15N HSQC spectra of a 50 μm solution of 15N-labeled recombinant GS-im23a in the absence and presence of 2.5 mm CaCl2 at pH 5.6 and 20 °C.

Structural Constraints

The TALOS+ program (12) was used to predict ϕ and ψ torsion angle restraints based on backbone chemical shifts. Predicted ϕ and ψ angles of residues that gave good prediction scores (25 residues: 8–18, 22–31, 34–35, 37, 41) were constrained in structure calculations in XPLOR. The final dihedral angle constraints are listed in Table 1 and have been deposited along with distance constraints in BioMagResBank (13) with accession number 18141. As disulfide bonds for im23a had not been determined unambiguously when structure calculations commenced, these were not included as structural restraints initially. After preliminary structure calculations, the disulfide bonding pattern was determined to be Cys-4–Cys-11, Cys-15–Cys-25, and Cys-26–Cys-41. These linkages were added as restraints for final structure calculations. Hydrogen bond restraints were included where the backbone amide was in slow or intermediate exchange with solvent, the magnitude of the amide temperature coefficient was smaller than 4 ppb/K in magnitude, and the acceptor was clearly defined in more than half of the structures calculated without any hydrogen bond restraints.

TABLE 1.

Structural statistics for im23a

| Distance restraints | 653 | |

| Intra (i = j) | 341 | |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 145 | |

| Short (1 〈| i − j | 〉 6) | 117 | |

| Long | 50 | |

| Dihedral restraints | 50 | |

| Energies (kcal mol−1)a | ||

| ENOE | 5.8 ± 1.6 | |

| Deviations from ideal geometryb | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0023 ± 0.0002 | |

| Angles (°) | 0.576 ± 0.019 | |

| Impropers (°) | 0.386 ± 0.010 | |

| Mean global r.m.s.d. (Å) c | Backbone heavy atoms | All heavy atoms |

| Residues 7–41 ((ϕ), S(ψ) > 0.8) | 1.14 ± 0.28 | 1.96 ± 0.28 |

| Ramachandran plotd | ||

| Most favored (%) | 72.7 | |

| Allowed (%) | 24.6 | |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 2.7 | |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 | |

a Values for ENOE were calculated from a square well potential with force constants of 50 kcal mol−1 Å2.

b Values for bonds, angles, and impropers show the deviations from ideal values based on perfect stereochemistry.

c The pairwise root mean square deviation over the indicated residues calculated in MOLMOL.

d Determined by the program PROCHECK-NMR for all residues except Gly and Pro.

Structure Calculations

Intensities of NOE cross-peaks were measured in XEASY and calibrated using the CALIBA macro of the program CYANA (Version 1.0.6) (14). NOEs providing no restraint or representing fixed distances were removed. The constraint list resulting from the CALIBA macro of CYANA was used in Xplor-NIH to calculate a family of 200 structures using the simulated annealing script (15). The 50 lowest energy structures were then subjected to energy minimization in water; during this process a box of water with a periodic boundary of 18.856 Å was built around the peptide structure, and the ensemble was energy-minimized based on NOE and dihedral restraints and the geometry of the bonds, angles, and impropers. From this set of structures, final families of 20 lowest energy structures were chosen for analysis using PROCHECK-NMR (16) and MOLMOL (17). In all cases the final structures had no experimental distance violations greater than 0.2 Å or dihedral angle violations greater than 5°. The structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (18) with code 2lmz. Structural figures were prepared using the programs MOLMOL (17) and PyMOL (26).

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

Experimental details are provided in supplemental data.

Bioassay

The biological activity of the native and recombinant conotoxins was tested by injection of toxins into mice intracranially or intravenously (tail vein) to assess the effects on mouse central and peripheral nervous systems, respectively. Peptides were dissolved in normal saline solution at different concentrations, and a fixed volume of 20 μl was injected into each mouse. The same volume of normal saline solution was used as a negative control.

RESULTS

Identification of im23a and im23b

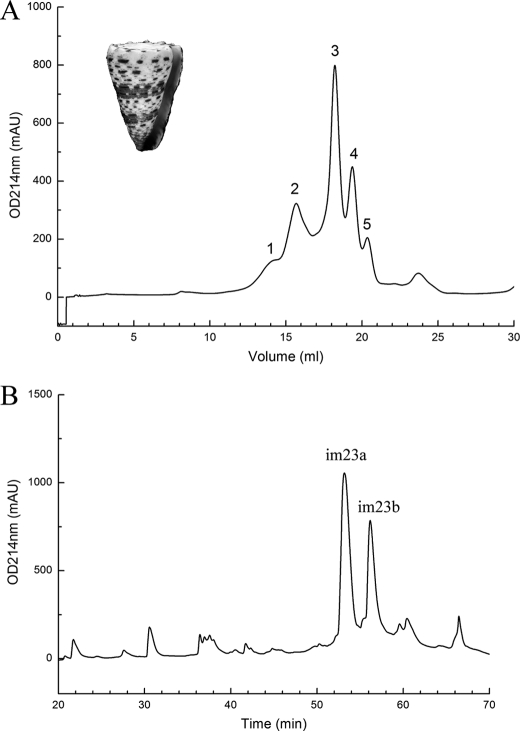

The crude venom of C. imperialis was first fractionated on a Superdex 75 HR10/30 column and then further separated on a PepmapTM C18 reverse-phase column (Fig. 1). From fraction 2 of the gel filtration column, two major peaks were purified. Their molecular masses were determined to be 4823.0 and 4874.0, respectively (data not shown). After being fully reduced and alkylated with iodoacetamide, their molecular masses shifted to 5171.0 and 5223.0, respectively, which suggests that both of these two toxins contain six cysteine residues forming three disulfide bonds. N-terminal sequencing showed that they have highly homologous sequences (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1.

Purification of im23a and im23b from the venom of C. imperialis. A, the crude venom extract of C. imperialis was separated on a Superdex 75HR 10/30 column in 30% acetonitrile. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. The inset shows a shell of C. imperialis. B, fraction 2 in panel A was further separated on RP-HPLC Pepmap C18 column with a linear gradient of 0–40% Buffer B in 85 min. The flow rate was 0.8 ml/min. The two major peaks were identified as im23a and im23b, respectively. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

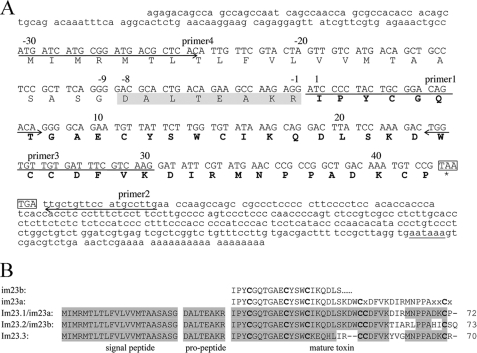

FIGURE 2.

The cDNA and protein sequences of im23a and im23b. A, shown are the cDNA and precursor sequence of im23a. The N-terminal 22 residues are predicted to be the signal peptide, whereas the shaded eight residues are the propeptide. The mature toxin sequence is shown in bold. The primers used for cDNA cloning are indicated with arrows. B, alignment of the determined and cDNA-encoded sequences of im23a and im23b is shown. Identical sequence are shaded.

Based on the determined N-terminal sequences, their cDNAs were cloned with 3′- and 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends methods (Fig. 2). The cDNA-encoded sequences clearly show that these two toxins are 42 and 43 amino acids long, respectively. The calculated molecular masses of these two sequences, 4823.56 and 4873.65 Da, are consistent with the determined masses of these two toxins, suggesting that they do not have other post-translational modification.

These two toxins contain a novel C-C-C-CC-C framework that has not been found previously in other conotoxins. We name it framework XXIII, and therefore, these two toxins are designated im23a and im23b; their cDNAs are numbered Im23.1 and Im23.2, respectively. According to the nomenclature proposed recently for all peptide toxins (19), im23a and im23b would be named U1-CTX-Ci1a and U1-CTX-Ci1b, respectively, but the simple names will be used throughout this paper.

cDNA of im23a Defines Novel Conotoxin Superfamily

Apart from the cDNAs corresponding to im23a and im23b, another closely-related cDNA, Im23.3, was also obtained (Fig. 2). These cDNA sequences have been deposited in NCBI GenBankTM with accession number FJ375238, FJ375239, and FJ375240. These three cDNAs encode a canonical conotoxin precursor composed of signal peptide, propeptide, and mature toxin regions. The signal peptide cleavage site is predicted to be between the 22nd residue Gly and the 23rd residue Asp. Their signal peptides are completely identical but clearly distinct from the signal peptide sequences of other known conotoxin superfamilies. According to the classification of conotoxins, these cDNAs belong to a novel conotoxin superfamily, which we name the K-superfamily.

It is remarkable that the propeptide of these cDNA-encoded precursors is only eight residues long, much shorter than the propeptide of other conotoxin precursors. Because the propeptide is believed to participate in the folding of conotoxins, the folding process of im21a and other homologous conotoxins may be quite unique. On the other hand, this short propeptide contains the typical double basic sequence KR at the C terminus, implying that this short propeptide shares a similar proteolytic cleavage mechanism.

In an effort to obtain cDNAs of other representatives of the K-conotoxin superfamily, primer 4 corresponding to its signal peptide sequence, was used as the forward primer to undertake PCR amplification from the following Conus species: C. quercinus, C. virgo, C. marmoreus, C. leopardus, and C. tessulatus. Only three cDNAs were obtained, one from C. marmoreus (Mr23.1, NCBI GenBankTM JQ235206), one from C. virgo (Vi23.1, NCBI GenBankTM JQ235207), and one from C. quercinus (Qc23.1, NCBI GenBankTM JQ235208). Interestingly, they are all very similar to Im23.1 and Im23.2 (data not shown). Mr23.1 encodes a precursor identical to the precursor of Im23.1, but the cDNA sequences are different at 52 nucleotide positions. Vi23.1 and Qc23.1 encode the same precursor sequence as Im23.2 but differ from Im23.1 at 4 and 3 nucleotide positions, respectively. This indicates that the K-conotoxin superfamily is not unique to C. imperialis, although the sequence of the mature toxins is quite conserved.

Recombinant Expression of im23a

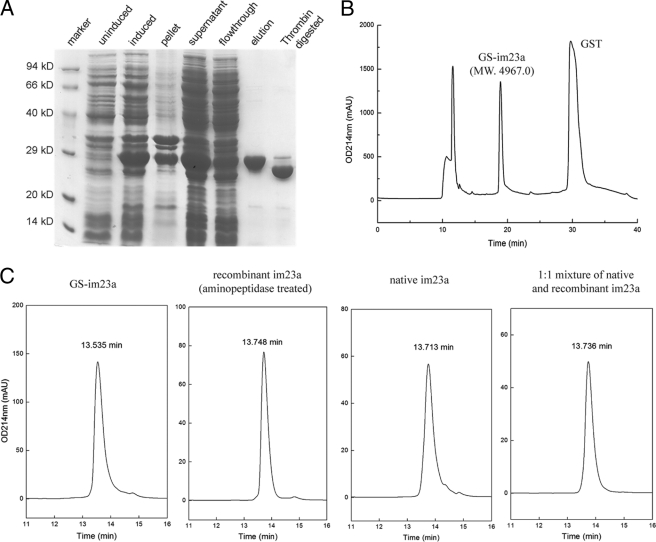

im23a was expressed in the soluble fraction as a GST fusion protein in Escherichia coli. After glutathione affinity purification, thrombin digestion, and RP-HPLC purification, recombinant im23a with two additional residues at the N terminus, GS-im23a, was obtained in good purity and yield (>10 mg/liter) (Fig. 3). The molecular mass of GS-im23a was determined to be 4967.0, consistent with the predicted value and showing that the three disulfide bonds were formed.

FIGURE 3.

Recombinant expression of im23a. A, SDS-PAGE of the expression and purification of im23a in E. coli is shown. The expression of GST-fused im23a was induced with isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and the fusion protein was purified with glutathione resin and then digested with thrombin. B, im23a released from GST after thrombin cleavage was purified on a RP-HPLC C18 analytical column with a linear gradient of 20–100% Buffer B in 3–43 min. The purified recombinant product had a molecular weight of 4967.0, consistent with the calculated value of 4967.6. C, coelution of recombinant and native im23a on RP-HPLC C18 analytical column is shown. The purified recombinant im23a with two fused residues at the N terminus (GS-im23a) was treated with Aeromonas aminopeptidase, giving a product without any fused residue that coelutes with native im23a. The elution gradient in panel C was as follows: 0–40% Buffer B in 0–5 min, 40–53% Buffer B in 5–18 min. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

To confirm that the recombinant im23a was correctly folded, GS-im23a was treated with Aeromonas aminopeptidase (EC 3.4.11.10). Because this aminopeptidase hydrolyzes the first peptide bond of a polypeptide chain until it recognizes a specific stop signal of -X-Pro, only the N-terminal Gly-Ser residues were removed by aminopeptidase treatment. Consequently, the molecular mass of the product shifted to 4823.0. The treated product coelutes with the native im23a on a RP-HPLC C18 analytical column (Fig. 3), clearly demonstrating that the recombinant im23a has the same fold as the native toxin. Further supporting evidence comes from the observation that the recombinant product has the same effect on mice as the native peptide (see below). Therefore, the recombinant GS-im23a was used for the disulfide connectivity determination and NMR structure analysis.

Disulfide Connectivity

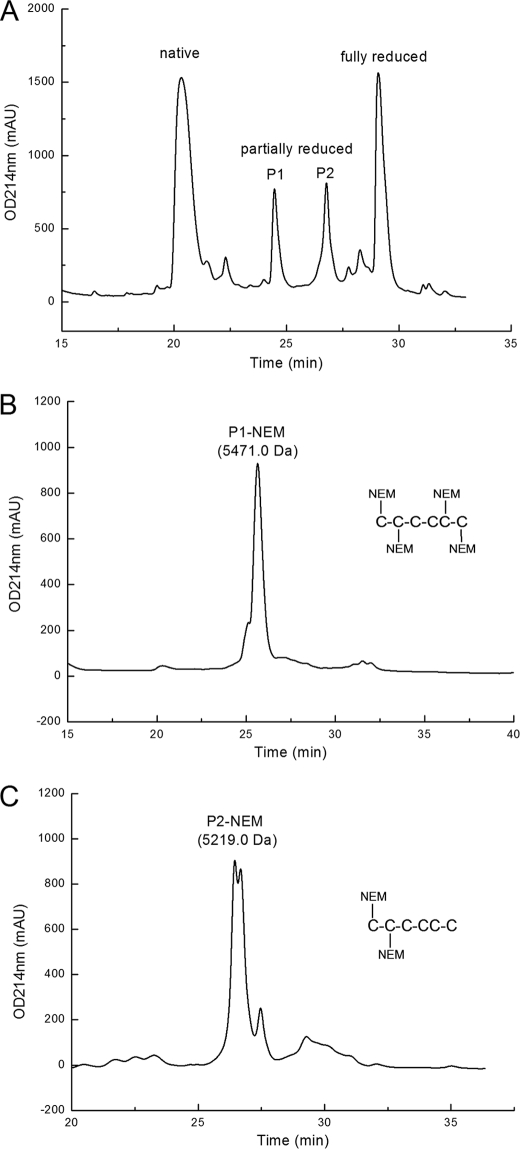

Partial reduction of GS-im23a by Tris-(carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride produced two intermediates, P1 and P2 (Fig. 4A), which were further alkylated with NEM and then purified by RP-HPLC (Fig. 4, B and C). The molecular masses of these two intermediates showed that P1 has two disulfide bonds reduced, and P2 has only one. They were directly subjected to Edman degradation sequencing to check the position of NEM-labeled Cys residues. P1 had NEM-Cys at four positions, Cys-4, Cys-11, Cys-26, and Cys-41, indicating that Cys-15 and Cys-25 are disulfide-linked in im23a. P2 had NEM-Cys only at positions Cys-4 and Cys-11, indicating that Cys-4 and Cys-11 were originally disulfide-linked. Thus, the third disulfide bond is between Cys-26 and Cys-41. Taken together, these data indicated that im23a adopts a unique sequential or “bead” pattern of disulfide connectivities, namely, I-II, III-IV, and V-VI, which has never been reported in peptides with three disulfide bonds.

FIGURE 4.

Disulfide connectivity determination of im23a. A, the partially reduced intermediates of im23a were separated on HPLC C18 column. B, NEM-alkylated P1 was purified on HPLC. The molecular weight of P1-NEM was determined to be 5471.0, showing that there are 4 NEM modification sites in this intermediate. The inset shows its NEM-Cys positions determined with Edman degradation sequencing. C, P2-NEM was similarly purified on HPLC C18 column. The two NEM-Cys positions are shown in the inset. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

The unexpected disulfide connectivities were confirmed independently by our structure calculations, which showed that only this pattern of disulfide bridges was consistent with the NMR restraints. This pattern was further confirmed by synthesizing im23a with orthogonal protecting groups (supplemental Figs. S1–S3). The resulting product gave an NMR spectrum (supplemental Fig. S4) identical to that of the recombinant peptide.

NMR Spectroscopy

Good quality spectra were obtained for im23a at pH 5.6 and 20 °C even though the peptide was prone to self-association and contained a minor conformer, as documented below. Distance restraints were obtained from the intensities of NOE cross-peaks at this temperature and pH. The fingerprint regions of TOCSY and NOESY spectra are shown in supplemental Fig. S5. Three-dimensional NOESY-HSQC and two-dimensional 1H,15N HSQC spectra were used to resolve peak overlap in the amide region. The 1H,15N HSQC spectrum of im23a is shown in supplemental Fig. S6. Chemical shift deviations of backbone amide and Cα protons from random coil values at 20 °C are shown in supplemental Fig. S7A. Chemical shift assignments are presented in supplemental Table S1 and have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (13) with accession number 18141.

The temperature dependence of amide proton chemical shift was determined to assess possible hydrogen bonding. Among those that could be experimentally measured, the backbone amide temperature coefficients for residues 6, 7, 10, 12–20, 23, 27–34, 39–41 were smaller than 4 ppb/K in magnitude (supplemental Fig. S7B), indicating that these amides were partially protected from solvent. Amide exchange experiments conducted at pH 5.6 and 20 °C indicated that amide protons of residues 12, 15–17, 27, 29–30, 32–33 exchanged relatively slowly as compared with the rest (supplemental Table S2).

Solution Structure of im23a

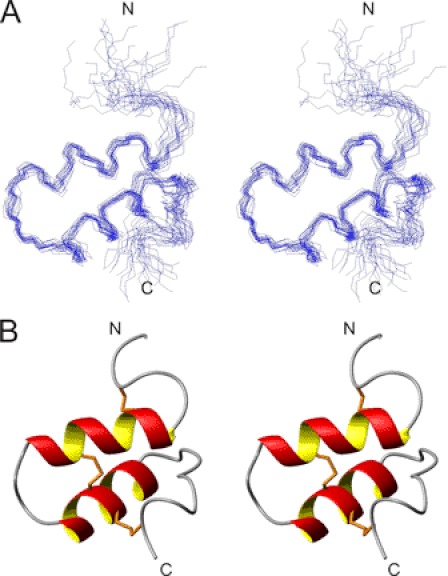

Stereo views of the closest-to-average structure of im23a in ribbon form showing secondary structure and a family of 20 final structures superimposed over backbone heavy atoms are shown in Fig. 5. A summary of experimental constraints and structural statistics for im23a is given in Table 1. The angular order parameters for ϕ and ψ angles in the final ensemble of 20 structures were both >0.8 over residues 7–41 (supplemental Fig. S8), indicating that ϕ and ψ angles of these residues are well defined within the family of structures. The mean pairwise root mean square deviation over the backbone heavy atoms of residues 7–41 in this family of structures was 1.14 Å. The closest-to-average structure of im23a is characterized by two α-helices encompassing residues 8–17 and 22–31 connected by a loop to form a hairpin. Medium-range NOEs (dαN(i,i+3) and dαN(i,i+4)) were observed in the helical regions. Chemical shift deviations from random coil values, temperature coefficients, and amide exchange results are all consistent with the helices observed in these regions. Residues 32–34 also had slow to intermediate amide exchange rates and low temperature coefficients, although they are not part of a helix. Instead, a turn is formed by these residues, leading to the C-terminal loop. Positive Hα chemical shift deviations from random coil values observed for Ile-32 and Met-34 support a deviation from helical structure in this region. Hydrogen bonds observed in at least 10 of 20 structures are listed in supplemental Table S2. The locations of side chains on the closest-to-average structure are shown in Fig. 6A. The two helices come together in a manner that arranges the hydrophobic residues within the molecule to form a hydrophobic core, whereas charged and polar residues generally point toward the surface.

FIGURE 5.

Stereo views of im23a structure. A, family of 20 final structures superimposed over backbone heavy atoms (N, Cα, C') over residues 7–41 is shown. B, closest-to-average structure of im23a in ribbon form depicts secondary structure. Disulfide bonds are shown in orange.

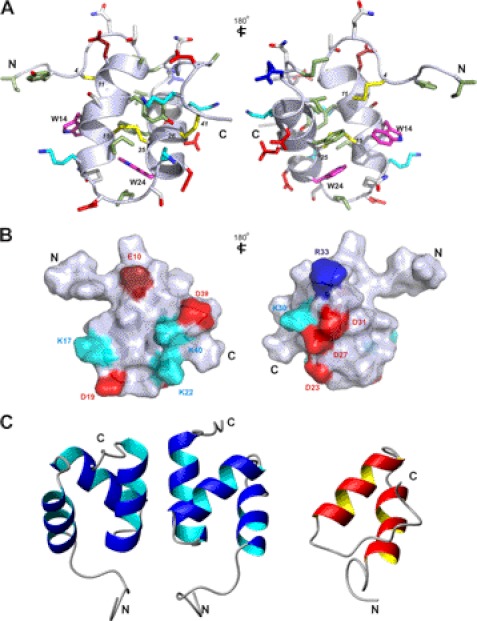

FIGURE 6.

A, shown is the closest-to-average structure of im23a with all side chain heavy atoms displayed. Disulfide bonds are shown in yellow; positively charged residues are colored blue, negatively charged residues are in red, hydrophobic residues are pale green, and tryptophan residues are in magenta. B, shown is a surface representation of im23a, highlighting charged residues. Surface is colored gray with basic residues in blue (Arg is in dark blue, and Lys is in light blue) and acidic residues in red (Glu is in dark red, and Asp is in red). The two views are related by a 180° rotation about the vertical axis. C, shown is a comparison of closest-to-average structures of ubiquitin-associated domain dimer of ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b (blue; PDB ID 2DO6) and im23a (red). Structures were superimposed over backbone heavy atoms (N, Cα, C′) for residues 7–34 of im23a and 8–35 of Cbl-b.

Effect of Concentration

Perturbations in chemical shift were observed for certain residues after a change of concentration from 1 to 0.3 mm, suggesting possible aggregation at higher concentrations. In particular, the indole proton peak of Trp-24 is a good indicator, as its peak intensity becomes relatively weaker at the higher concentration of 1 mm in addition to a significant change in its chemical shift. In contrast, the intensity and chemical shift of the Trp-14 indole proton peak remains relatively unaffected by changes in concentration. Weighted average chemical shift differences for amide 1H and 15N chemical shifts of im23a, pH 5.6, between 1H,15N HSQC spectra at 1 and 0.3 mm are plotted in supplemental Fig. S9A. Resonances with significant change (Δδav > 0.2 ppm) in chemical shift were mapped onto the closest-to-average structure in supplemental Fig. S9, B and C. The residues most affected lie toward the second helix (Trp-24, Cys-25, Asp-27, Phe-28, Val-29, Asp-31, Ile-32, Arg-33) bearing the Trp-24 residue, although a few residues toward the N terminus (Ile-1, Gln-6, and Thr-7) seem to be affected as well. Sedimentation velocity studies of 15N-labeled im23a indicate that the sample at a concentration of 0.4 mm exists in a monomer-dimer equilibrium (supplemental Figs. S10 and S11 and Table S3).

Minor Conformer

A set of minor resonances was observed in the spectra in a ratio of ∼1:4 compared with the major resonances. Residues that exhibit well resolved major and minor resonances are highlighted in supplemental Fig. S12A. Weighted average chemical shift perturbations between 1H and 15N chemical shifts of major and minor peaks are plotted as a function of residue in supplemental Fig. S12B. Assigned minor resonances are mapped onto the closest-to-average structure in supplemental Fig. S12C. A similar set of peaks was observed for an unlabeled sample of im23a. It is possible that these extra peaks arise from the presence of a disulfide isomer, as affected residues are around the region of the Cys-15–Cys-25 and Cys-26-Cys-41 disulfide bonds. Another possibility could be proline cis-trans isomerism, as there are four proline residues in im23a, including a pair of adjacent residues in the Cys-26- Cys-41 loop (Pro-36 and Pro-37) and the C-terminal Pro-42. Analysis of NOEs between resonances from proline residues of the major conformer and those of their preceding residues confirms that all prolines in the major conformer adopt a trans conformation, as indicated by the strong Hα(i)-Hδ(i+1) NOEs in the NOESY spectrum. Analysis of minor peaks in 13C-1H HSQC spectra suggests that the minor conformer arises as a result of a cis conformation for the peptide bond preceding one of the proline residues, based on Cβ chemical shifts for a cis-proline. In particular, two minor peaks at 2.23 and 2.13 ppm in the 13C-1H HSQC spectra have a 13C chemical shift of 34.3 ppm, typical of that for Cβ in a cis-proline. However, the identity of the relevant proline cannot be confirmed unambiguously because of peak overlap in the spectra.

Biological Activities of im23a and im23b

The biological effect of crude venom from C. imperialis as well as native im23a and im23b and recombinant im23a were tested on 2-week-old (P14) and 6-week-old (P42) Kunming male mice. Intracranial injection of crude venom into P14 mice resulted in excitotoxic symptoms, including rapid circular running, seizures, and scratching. The injection of im23a or im23b into the mouse brain induced similar excitatory symptoms. For P14 mice, a dose of 20 μg/mouse caused the tested mice to squint and become hypersensitive to touch and susceptible to screaming when touched. These symptoms lasted for 5 min. In comparison, injection of the same volume of normal saline solution did not produce any observable symptoms. At a dose of 40 μg/mouse, symptoms became more severe and included circular or random running, seizures, or being lethargic. For P42 mice, the same doses induced much milder symptoms (supplemental Table S4). Similar effects were observed for recombinant im23a, arguing for the correct folding of recombinant product. By contrast, no obvious symptoms were observed after intraperitoneal or intravenous (tail vein) injection of 40 μg of im23a into the P14 mouse, which implies that im23a probably has no effect on the peripheral nervous system (n ≥ 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have described the isolation and chemical characterization of two novel cone shell toxins, im23a and im23b, from C. imperialis. We have also determined the solution structure of im23a and characterized its biological activity in mice. The helical hairpin motif in the structure of im23a is unique and, to our knowledge, has never been reported for any previously described conotoxin. Indeed, toxins from other species (scorpions, spiders, etc.) with helical motifs are quite rare.

A search using DALI (20), which interrogates the Protein Data Bank data base for structural homologues, showed that im23a had structural similarities to the ubiquitin-associated domain of the ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b (PDB ID 2DO6), which exists naturally as a dimer (21, 22). An overlay of the two structures shows that the first two helices across the hairpin motif matched well with each other. However, the C-terminal tails had significantly different orientations (Fig. 6C). The ubiquitin-associated domain consists of a compact three-helix bundle stabilized by a hydrophobic core (22); unlike im23a, the ubiquitin-associated domain does not contain any disulfide bonds to stabilize the structure. Several aspects of the NMR data for im23a (amide exchange rates, 3JHNHA values, backbone chemical shifts, lack of medium-range NOEs) show quite clearly that its C-terminal region is not helical under the solution conditions examined here, and the Cys-26 to Cys-41 disulfide bridge dictates that the orientation of the C-terminal region is distinct from that in Cbl-b. The presence of proline residues at positions 36 and 37 presumably affects the folding pathway of im23a and contributes to its final topology, which is then stabilized by disulfide bridges; the Cbl-b domain shown in Fig. 6 lacks proline residues. The dimer interface of Cbl-b lies between the second helix and the C-terminal helix, with a charged interaction occurring between Arg-28 on the second helix of one subunit and Glu-46 on the C-terminal helix of its partner in the dimer. As a consequence of the different orientation of the C-terminal region and different positions of charged residues in im23a, it is likely that im23a dimerizes in a different manner from Cbl-b.

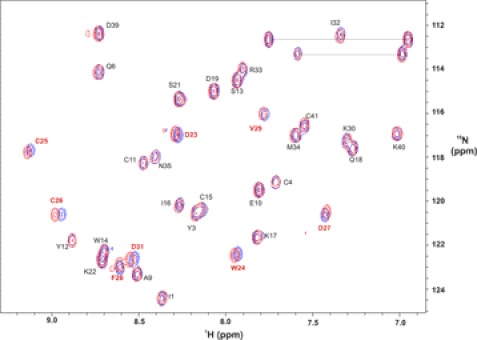

A surface representation of im23a highlighting charge distribution (Fig. 6B) shows that the molecule has two distinct charged surfaces. Asp-23, Asp-27, and Asp-31 align along one face of the second helix, forming an “aspartate patch” on one surface of the toxin. The exact role of the charged residues and the aspartate patch has yet to be determined. Alanine mutations should reveal which of these residues is functionally important. Preliminary Ca2+ binding studies by NMR indicated perturbations in 15N and 1H chemical shifts of residues on the second helix bearing the aspartate patch (Asp-23–Asp-31) upon the addition of a 50-fold molar excess of Ca2+ (Fig. 7). Perturbations in chemical shifts were not observed in the presence of 50 μm EDTA (supplemental Fig. S13). It is possible that the charged surface bearing the aspartate residues may also influence the observed aggregation at higher concentrations. At pH < 5, the Trp-24 indole resonance shifts upfield and broadens significantly, whereas the corresponding Trp-14 resonance is unaffected. It is noteworthy that a number of hydrophobic residues on this helix (Trp-24, Phe-28, Val-29, and Ile-32) are affected by aggregation, implying that they also contribute to the intermolecular interface.

FIGURE 7.

1H,15N HSQC spectrum of 15N-labeled im23a (50 μm, pH 5. 6) acquired at 20 °C on a Bruker Avance-600 spectrometer in the absence (blue) and presence (red) of 2.5 mm CaCl2. Peaks are labeled in black, with residues displaying perturbations in red.

Im23a has a relatively long amino acid sequence compared with most other conotoxins, which often contain only 10–30 residues. Typically, both the signal peptide sequence and cysteine framework can be used to classify conotoxins, as these features are relatively well conserved as compared with non-cysteine residues in the mature peptide. Im23a has a cysteine framework (C-C-C-CC-C) not observed previously in conotoxins. Moreover, its sequential bead disulfide connectivity (I-II, III-IV, V-VI) is also not a commonly observed pattern among toxins. An analysis of the signal sequence of im23a using ConoServer (9) could not clearly classify it into a known superfamily, although its signal peptide sequence has greatest similarities with the A and I1 superfamily. Thus, im23a belongs to a new superfamily of Conus peptides that we designate the K-superfamily.

The disulfide bond connectivities of im23a were determined by both chemical mapping and analysis of structures calculated using NMR-derived restraints, then confirmed by the 1H NMR spectrum of the synthetic toxin prepared using orthogonal protection of individual cysteine residues. The unexpected I-II/III-IV/V-VI (or bead) pattern emphasizes the importance of determining disulfide connectivities experimentally rather than by analogy with other peptides with similar cysteine frameworks. This was well illustrated by previous findings for the I-superfamily conotoxin ι-RXIA (23), which has the same pattern of connectivities as the Sydney funnel-web spider toxin, robustoxin, i.e. I-IV/II-VI/III-VII/V-VIII (24). However, in a different spider toxin, J-atracotoxin, which shares an identical cysteine framework with the I-conotoxins, the cysteine connectivities were quite distinct, i.e. I-VI/II-VII/III-IV/V-VIII (25), even though ι-RXIA is more similar to J-atracotoxin in terms of spacing between cysteine residues than to some other members of its own I-superfamily. Thus, different cysteine frameworks but the same disulfide connectivities (as in ι-RXIA and robustoxin), can produce similar structures, whereas the same frameworks (as in ι-RXIA and J-atracotoxin) do not necessarily lead to the same disulfide connectivities.

Although the im23 toxins displayed excitatory effects in mice, their mechanism of action remains unknown. In an effort to identify their biological target, im23a and im23b were tested on the NaV1.7 channel, Drosophila Shaker channel, and rat Slo1 channel expressed in HEK293 cell as well as on whole cell current of neurons from neonatal rat hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. However, no effect was observed with toxins up to 50 μm (data not shown). In addition, no detectable effect was observed on either action potential amplitude and duration or Na+ and Ca2+ current amplitude and kinetics when im23a was tested on action potentials and depolarization-activated Na+ and Ca2+ currents in rat DRG neurons. Further work will be required to identify the target channel/receptor of toxins of this family.

In conclusion, we have isolated and characterized two novel conotoxins that contain a unique cysteine framework (C-C-C-CC-C), with an unusual pattern of disulfide bridges (I-II, III-IV, V-VI). The solution structure of im23a reveals that this toxin adopts a novel helical hairpin fold. Preliminary studies reveal that charged residues on the second helix may play a role in aggregation and Ca2+ binding. Further mutational studies of im23a will be required to probe aggregation and metal binding in greater detail. Further work will also be required to identify the biological target of these new toxins, which induce excitatory symptoms in mice after intracranial administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Frederick Sigworth and Dr. Youshan Yang, Yale University School of Medicine, and Professor David Adams, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, for electrophysiological assays of im23a and im23b.

This work was supported in part by Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology Grant 2010CB529802 and by Chinese Ministry of Education Grant NCET-10-0604.

This article contains supplemental data, Figs. S1–S14, and Tables S1–S4.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2lmz) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) FJ375238, FJ375239, and FJ375240.

NMR chemical shift data and NMR-derived structural restraints have been deposited in the BioMagResBank Data Bank with accession number 18141.

- RP

- reverse phase

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- TOCSY

- two-dimensional homonuclear total correlation

- NOESY

- nuclear overhauser enhancement.

REFERENCES

- 1. Norton R. S., Olivera B. M. (2006) Conotoxins down under. Toxicon 48, 780–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Terlau H., Olivera B. M. (2004) Conus venoms. A rich source of novel ion channel-targeted peptides. Physiol. Rev. 84, 41–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armishaw C. J., Alewood P. F. (2005) Conotoxins as research tools and drug leads. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 6, 221–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McIntosh J. M., Olivera B. M., Cruz L. J. (1999) Conus peptides as probes for ion channels. Methods Enzymol. 294, 605–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han T. S., Teichert R. W., Olivera B. M., Bulaj G. (2008) Conus venoms. A rich source of peptide-based therapeutics. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 2462–2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Livett B. G., Gayler K. R., Khalil Z. (2004) Drugs from the sea. Conopeptides as potential therapeutics. Curr. Med. Chem. 11, 1715–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Norton R. S. (2010) μ-conotoxins as leads in the development of new analgesics. Molecules 15, 2825–2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidtko A., Lötsch J., Freynhagen R., Geisslinger G. (2010) Ziconotide for treatment of severe chronic pain. Lancet 375, 1569–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaas Q., Westermann J. C., Halai R., Wang C. K., Craik D. J. (2008) ConoServer, a database for conopeptide sequences and structures. Bioinformatics 24, 445–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bartels C., Xia T. H., Billeter M., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (1995) The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral-analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sattler M., Schleucher J., Griesinger C. (1999) Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Progr. NMR Spectrosc. 34, 93–158 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. (2009) TALOS+. A hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 44, 213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ulrich E. L., Akutsu H., Doreleijers J. F., Harano Y., Ioannidis Y. E., Lin J., Livny M., Mading S., Maziuk D., Miller Z., Nakatani E., Schulte C. F., Tolmie D. E., Kent Wenger R., Yao H., Markley J. L. (2008) BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D402–D408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herrmann T., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (2002) Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE identification in the NOESY spectra using the new software ATNOS. J. Biomol. NMR 24, 171–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwieters C. D., Kuszewski J. J., Tjandra N., Clore G. M. (2003) The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laskowski R. A., Rullmannn J. A., MacArthur M. W., Kaptein R., Thornton J. M. (1996) AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR. Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8, 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. (1996) MOLMOL. A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berman H. M., Battistuz T., Bhat T. N., Bluhm W. F., Bourne P. E., Burkhardt K., Feng Z., Gilliland G. L., Iype L., Jain S., Fagan P., Marvin J., Padilla D., Ravichandran V., Schneider B., Thanki N., Weissig H., Westbrook J. D., Zardecki C. (2002) The Protein Data Bank. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 899–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. King G. F., Gentz M. C., Escoubas P., Nicholson G. M. (2008) A rational nomenclature for naming peptide toxins from spiders and other venomous animals. Toxicon 52, 264–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server. Conservation mapping in three-dimensional. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peschard P., Kozlov G., Lin T., Mirza I. A., Berghuis A. M., Lipkowitz S., Park M., Gehring K. (2007) Structural basis for ubiquitin-mediated dimerization and activation of the ubiquitin protein ligase Cbl-b. Mol. Cell 27, 474–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhou Z. R., Gao H. C., Zhou C. J., Chang Y. G., Hong J., Song A. X., Lin D. H., Hu H. Y. (2008) Differential ubiquitin binding of the UBA domains from human c-Cbl and Cbl-b. NMR structural and biochemical insights. Protein Sci. 17, 1805–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buczek O., Wei D., Babon J. J., Yang X., Fiedler B., Chen P., Yoshikami D., Olivera B. M., Bulaj G., Norton R. S. (2007) Structure and sodium channel activity of an excitatory I1-superfamily conotoxin. Biochemistry 46, 9929–9940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pallaghy P. K., Alewood D., Alewood P. F., Norton R. S. (1997) Solution structure of robustoxin, the lethal neurotoxin from the funnel-web spider Atrax robustus. FEBS Lett. 419, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang X., Connor M., Smith R., Maciejewski M. W., Howden M. E., Nicholson G. M., Christie M. J., King G. F. (2000) Discovery and characterization of a family of insecticidal neurotoxins with a rare vicinal disulfide bridge. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Delano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Delano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.