Background: Viral E3 ubiquitin ligases use distinct mechanisms to degrade proteins required for antigen presentation.

Results: Novel viral ligase, pK3, binds to MHCI proteins and induces degradation of MHCI and associated ER chaperones.

Conclusion: pK3 uses a novel mechanism to recognize substrates and block antigen presentation.

Significance: Demonstrates the importance of transmembrane interactions in E3:substrate interaction and ER quality control.

Keywords: Antigen Presentation, ER Quality Control, ER-associated Degradation, Ubiquitylation, Viral Protein

Abstract

Viral immune invasion proteins are highly effective probes for studying physiological pathways. We report here the characterization of a new viral ubiquitin ligase pK3 expressed by rodent herpesvirus Peru (RHVP) that establishes acute and latent infection in laboratory mice. Our findings show that pK3 binds directly and specifically to class I major histocompatibility proteins (MHCI) in a transmembrane-dependent manner. This binding results in the rapid degradation of the pK3/MHCI complex by a mechanism dependent upon catalytically active pK3. Subsequently, the rapid degradation of pK3/MHCI secondarily causes the slow degradation of membrane bound components of the MHCI peptide loading complex, tapasin, and transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP). Interestingly, this secondary event occurs by cellular endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Cumulatively, our findings show pK3 uses a unique mechanism of substrate detection and degradation compared with other viral or cellular E3 ligases. More importantly, our findings reveal that in the absence of nascent MHCI proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, the transmembrane proteins TAP and tapasin that facilitate peptide binding to MHCI proteins are degraded by cellular quality control mechanisms.

Introduction

Viral E3 ubiquitin ligases that function as immune evasion proteins have provided several recent insights into degradation pathways of importance for antigen presentation. The most notable of these are the immune evasion proteins mK32 of γ-herpesvirus 68 (γHV68) as well as kK3 and kK5 (also known as MIR1 and MIR2) of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). These viral immune evasion proteins are the founding members of a large family of highly homologous viral and cellular ubiquitin ligases that have been collectively designated the MARCH (membrane-associated, RING-CH) proteins (1, 2). The CH denotes the unique zinc-contacting residues in the RING domain that confer ubiquitin ligase activity (3, 4). All three of these viral MARCH proteins are type III proteins whereby their conserved N terminus containing the RING-CH domain is followed by two membrane passages, which is then followed by a C-terminal domain variable in length and sequence between viral MARCH (vMARCH) proteins (5, 6). This domain organization results in both the N- and C-terminal domains of viral MARCH proteins in the cytosol and a very short (about 12 amino acids) segment in the ER lumen. The exposure of the RING-CH domain to the cytosol allows the viral ligases to interact with the other ubiquitin components required for substrate conjugation.

Despite their highly homologous RING-CH domains, common topology, and the fact that all three target MHCI proteins, mK3, kK3, and kK5 viral ligases have fundamental differences. Most notably, mK3 ligase targets ER resident MHCI proteins awaiting peptide loading for degradation in the cytosol by the proteasome (5, 7, 8). By contrast the kK3 and kK5 ligases target fully assembled MHCI proteins at the plasma membrane for endocytosis and degradation in the lysosome (9–13). The viral ligases mK3, kK3, and kK5 also have different substrate specificity. The mK3 ligase primarily targets MHCI heavy chains (HC), whereas they are associated with the peptide loading complex (5, 7, 8). By contrast, kK3 appears to target all classical human MHCI proteins as well as non-classical CD1d (14), and kK5 targets a subset of classical MHCI proteins, CD1d, as well as multiple other immune regulatory molecules including the T cell co-stimulatory molecules ICAM-1 and B7.2 and the NK cell ligands MICA, MICB and AICL, and CD31 (PECAM) (14–17). In addition to cellular immunity, the kK3 and kK5 ligases were also shown to reduce the expression of the γ interferon receptor 1, which may be involved in KSHV-induced tumor propagation (18). As recently reviewed, these vMARCH proteins have been used to define molecular pathways that are now paradigms for how proteins are targeted for proteasome versus lysosomal degradation (1, 19). Although these degradation pathways defined by viral ligases are among the best delineated, the molecular basis of their differences in substrate specificity and location of degradation are incompletely understood.

The identification of viral MARCH proteins in both Herpesviridae and Poxviridae, two divergent dsDNA virus families, led to speculation that they were purloined from their mammalian host (4). Supporting this speculation, 11 cellular MARCH proteins have been identified in mice with matching homologs in humans (2, 20). Although less is known about other cellular MARCH proteins, they appear to have diverse tissue expression, subcellular localization, and putative physiological functions (21). Furthermore, recent studies have revealed mechanistic similarities between MARCH1 regulation of MHCII proteins and kK3/kK5 regulation of MHCI proteins (22). Based on the ability of using vMARCH proteins to elucidate novel features of ubiquitin-dependent degradation pathways, we characterize here a novel vMARCH homolog from the newly discovered and sequenced virus rodent herpesvirus Peru (RHVP) (23). RHVP was isolated from a lung homogenate of a pygmy rice rat, and it establishes acute and latent infections in laboratory mice. Furthermore, the recently annotated genomic sequence of RHVP contains genes conserved in γ-herpesvirus strains and has a similar overall gene organization as γHV68 and KSHV (23). Of particular interest, the RHVP genome ORF R12 was also predicted to encode a unique K3 homolog (designated pK3 for Peru K3) with a signature RING-CH domain. We show here that pK3 induces ER associated degradation (ERAD) of MHCI proteins that secondarily causes the destabilization of the transmembrane (TM) components (TAP and Tpn) but not the soluble components (β2m, Erp57, and calreticulin (CRT)) of the peptide loading complex (PLC). Our observations underscore the dependence of TM components of the PLC on MHCI expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines

Murine embryo fibroblast (MEF) B6/WT3 (WT3) and mutant MEFs including TAP1-deficient cells (FT1−), tapasin-deficient cells (Tpn−/−), calreticulin-deficient cells (CRT−/−), β2m-deficient cells (β2m−/−). and triple knock-out fibroblasts (Kb−/− Db−/− β2m−/−; 3KO) were all derived from C57BL/6 (H-2b) embryos (7). Mouse L-cell fibroblasts and human C1R cells have been described previously (24, 25). The pK3 and Ld and their mutants were stably expressed in the indicated cells by retroviral expression vectors pMIG and pMIN (7, 26), respectively. Cells transduced by pMIN were selected by neomycin, whereas GFP+ cells from pMIG-transduced lines were enriched by cell sorting. Mouse Tpn and β2m were fed back to Tpn−/− and b2m− cells by transduction with the vector expressing IRES-hygromycin. Where indicated, cells were cultured for 24 h with 125 units/ml of mouse γ interferon (IFNγ, BIOSOURCE, Sunnyvale, CA) and for 2–4 h with proteasome inhibitor 30–50 μm MG132 (Boston Biochem, Bambridge, MA) or 10–20 μm epoxomicin before harvesting with trypsin-EDTA.

DNA Constructs

pK3 sequence from RHVP (23) were amplified by PCR from cDNA pool of RHVP-infected Vero cells. The pK3 RING mutant (C86G, C89G) (RM) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). Ld cytoplasmic tail mutants (K-less or KCST-less) were previously described (27). Human influenza hemagglutinin epitope (HA)-tagged pK3 and Ld/huB7.2 chimeric molecules (Ld/hB7.2 TAIL and Ld/hB7.2 TM-TAIL) were obtained by overlap PCR.

Antibodies

A rabbit antiserum to amino-terminal sequences of pK3 (residues 3–21) was generated by immunization with keyhole limpet hemocyanin-coupled peptide. Rabbit anti-mouse TAP1, Erp57, and hamster anti-mouse Tpn (5D3) has been described (28, 29). Rabbit anti-TAP2 was a gift of Dr. Michael R. Knittler (University of Koln). Ubiquitin antibody (P4D1), β-actin antibody (AC-74), green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody, rabbit anti-CRT, rabbit anti-calnexin, and monoclonal anti-HA (clone 16B12) were purchased from Santa Cruz, Sigma, Covance, Stressgen, and Covance, respectively. Antibodies to cytoplasmic tail of Ld and Db (Ra20873) and the cytoplasmic tail of Kb (Ra3774) were produced in rabbits immunized with the cytoplasmic tail peptide (30). mAb 64-3-7 and 30-5-7 are specific to peptide-unloaded and peptide-loaded forms of Ld (25, 31, 32). All other MHCI mAbs including B8-24-3 for Kb, 15-5-5 for Dk, 11-4-1 for Kk, and W6/32 and HC10 for human HLA-B were previously described and available from the ATCC collection.

Immunoprecipitations and Immunoblots

For co-immunoprecipitations, cells were lysed in PBS with 1.0% digitonin (Wako, Richmond, VA) and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science) for 1 h. For immunoprecipitations, cells were lysed in PBS with 1% Nonidet P-40 instead. Post-nuclear lysates were then incubated with indicated antibodies plus Protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) or anti-HA-Sepharose (Sigma) for HA-tagged pK3. After washes, precipitated proteins were eluted by boiling in LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Specific proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence using the ECL system (Thermo).

Metabolic Labeling and Pulse-Chase

After 30 min of preincubation in Cys- and Met-free medium (MEM-Earle's with 5% dialyzed FCS), cells were pulse-labeled with Express [35S]Cys/Met labeling mix (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) at 200 μCi/ml for 15 min. Chase was initiated by the addition of an excess of unlabeled Cys/Met (5 mm each). Immunoprecipitation was performed as described above. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and revealed by autoradiography. Where indicated, cells were treated with proteasome inhibitors during preincubation and pulse-chase.

Flow Cytometry

All flow cytometric analyses were performed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Staining was performed as described (8). Phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (BD Pharmingen) was used to visualize MHCI staining. GFP signal representing pK3 transduced cells were collected in the FITC channel.

Cell Permeabilization and Ubiquitination

Cell permeabilization and ubiquitination were performed as described (33). Briefly, after washing with PBS twice, the cells were resuspended in PB buffer (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 115 mm KOAc, 5 mm NaOAc, 2.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm EGTA) containing 0.02% digitonin (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) at 0.5–1.0 × 107/ml and incubated on ice for 20 min. Soluble cytosolic proteins were squeezed out by centrifugation at 18,000 × g, 4 °C for 20 min and washed once with PB buffer. These soluble protein-depleted cells were then incubated for 45 min at 37 °C with 2.5 mg/ml Fraction II from rabbit reticulocyte extract (BostonBiochem), 20 μm HA-ubiquitin, and an ATP-regenerating system in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, buffers containing 1 mm PMSF, 50 μm MG132, and 2 μm deubiquiting enzyme inhibitor ubiquitin aldehyde (BostonBiochem). After incubation, ubiquitinated HCs were visualized by immunoprecipitation of Ld molecules and then blotting for tagged ubiquitin by anti-HA antibody.

RESULTS

pK3 Is Viral MARCH E3 Ligase That Down-regulates Surface MHCI Protein Expression

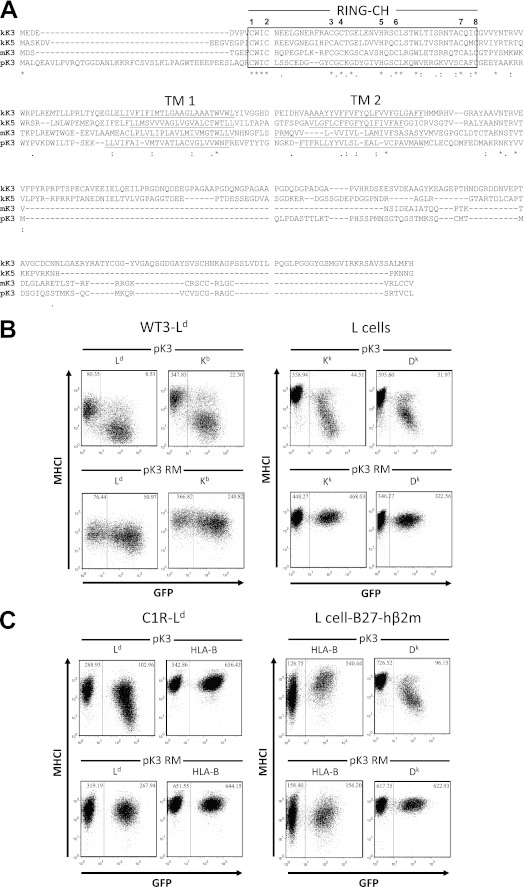

The recent sequencing and annotation of the RHVP genome revealed the presence of multiple ORFs predicted to encode proteins involved in viral immune evasion (23). One putative immunevasin discovered in the genome of this novel γ-herpesvirus (ORF R12) was predicted to encode a vMARCH ubiquitin ligase we designated Peru K3 (pK3). Similar to other vMARCH proteins, mK3, kK3, and kK5, pK3 contains two predicted TM domains (underlined in Fig. 1A) and thus is very likely to have type III membrane topology with both its N and C termini located in the cytosol (Fig. 1A). Additionally, the canonical MARCH zinc binding RING-CH domain (CX2CX10–45CX1CX7HX2CX11–25CX2C) is located in its N-terminal cytosolic domain (RING-CH domain, boxed). To determine whether pK3 is a functional E3 ubiquitin ligase, we tested its enzymatic activity using an auto-ubiquitination assay. In this assay the N-terminal RING-CH containing soluble domains of either pK3 or mK3 and their respective non-catalytic RING-CH mutant forms (pK3 RM and mK3 RM) were tested for their ability to auto-ubiquitinate in the presence of E1, E2 (UbcH5c), free ubiquitin, and ATP. As predicted, the soluble pK3 demonstrated strong auto-ubiquitination as evidenced by the dark smear detected in the antiubiquitin blot that was not present in the pK3 RM (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

pK3 is a viral MARCH E3 ligase that down-regulates mouse MHCI from the surface of murine cells. A, alignment of pK3 with other vMARCH E3 ligases is shown. The pK3 ORF was confirmed by sequencing cDNA isolated from RHVP-infected Vero cells. The amino acid sequences of pK3 (ORF R12) (23), mK3 (ORF K3) (57), kK3 (also known as MIR1) (ORF K3), and kK5 (also known as MIR2) (ORF K5) (34) were aligned using the T-COFFEE algorithm, and identical, highly conserved, and similar residues are specified by asterisks (*), colons (:), and periods (.), respectively. The two TM domains of each vMARCH are underlined, and the aligned RING-CH domain (CX2CX10–45CX1CX7HX2CX11–25CX2C) is boxed. Each of the eight conserved zinc-coordinating Cys and His residues in the RING-CH domain is numbered, and combined mutation of both the 7th and 8th zinc coordinating residues from Cys to Gly results in a non-catalytic RING mutant form of pK3 (pK3 RM). B, B6/WT3-Ld (H-2b, left four panels) and L cell (H-2k, right four panels) murine fibroblasts were transduced with pMIG-pK3 (pK3) or pMIG-pK3 RM (pK3 RM). Surface expression of murine MHCI alleles (y axis) versus GFP fluorescence (x axis) was monitored. The GFP+ (left boxes) and GFP− populations (right boxes) in each cell line represent the pMIG transduced and non-transduced cells, respectively. The numbers in the upper corners of both sections of each plot represent the median level of surface MHCI staining on the population within each box. C, human (HLA-B) fibroblasts stably expressing the murine MHCI allele Ld (C1R-Ld, left four panels) and murine (H-2k) fibroblasts stably expressing the human MHCI HLA B27 allele and human β2m (L cell.B27.hβ2m, right four panels) were transduced with pMIG-pK3 (pK3) or pMIG-pK3 RM (pK3 RM). Surface expression of murine MHCI alleles (y axis) versus GFP fluorescence (x axis) was monitored. The GFP+ (right boxes) and GFP− populations (left boxes) in each cell line represent the pMIG transduced and non-transduced cells, respectively. The numbers in the upper corners of both sections of each plot represent the median level of surface MHCI staining on the population within each box.

Aside from the conservation within the RING-CH domain, the sequence of pK3 is highly divergent from the other ligases (Fig. 1A), suggesting it might be functionally and mechanistically distinct from other vMARCHs. To determine whether pK3, like mK3, kK3, and kK5, down-regulates surface MHCI protein expression, murine fibroblasts were transduced to stably express either pK3 and GFP or a catalytically inactive pK3 RING mutant and GFP. As shown in Fig. 1B, expression of pK3 resulted in a sharp diminution of surface expression of Ld, Kb, Kk, and Dk alleles in murine fibroblasts in a RING-CH-dependent manner. Although pK3 facilitated the potent down-regulation of MHCI, surface levels of MHCII, ICAM-1, and B7.1 were unaffected by pK3 expression (supplemental Fig. S2).

vMARCH ligases display different degrees of species restriction in their capacity to down-regulate their substrates. Importantly, these restrictions can be quite informative as they are based on the underlying mechanisms of substrate recognition and down-regulation. To determine whether pK3 down-regulation of MHCI was restricted by species, we tested whether human and mouse MHCI proteins were susceptible to surface down-regulation by pK3 in human cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, mouse MHCI protein Ld ectopically expressed in human cells (C1R-Ld) was potently down-regulated by pK3 in a RING-dependent manner, whereas endogenous human MHCI remained unaffected. Reciprocally, in mouse L cells, only the endogenous Dk proteins were down-regulated and not ectopically expressed human MHCI protein HLA-B27 (Fig. 1C). In fact in the presence of pK3 there was a significant increase in B27 expression, likely reflecting the lack of competition with mouse MHCI proteins for assembly and expression. These results demonstrate that pK3 specifically down-regulates mouse and not human MHCI proteins, and this down-regulation is not dependent on species-different host factors.

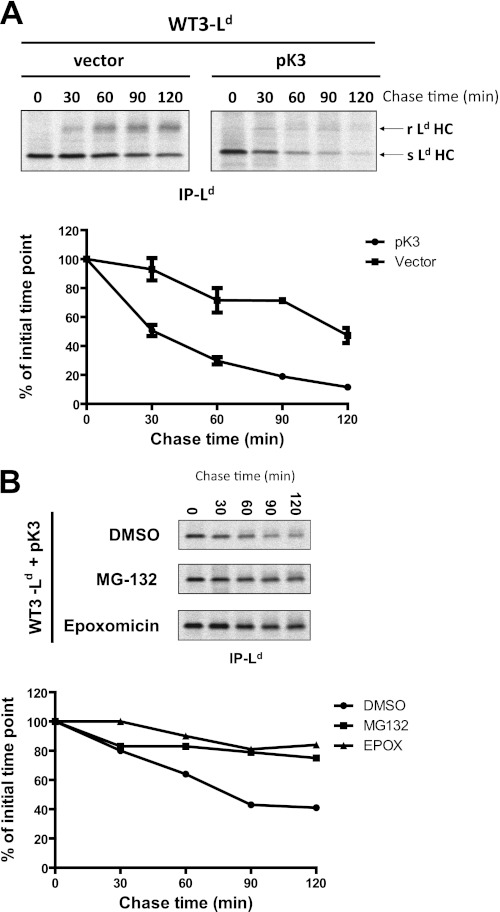

pK3 Induces ERAD of Nascent MHCI

To determine the mechanism used by pK3 to regulate MHCI protein expression, we first measured the turnover kinetics of MHCI protein Ld with and without concomitant expression of pK3. As shown in Fig. 2A, metabolically labeled MHCI in the pK3 expressing cells had a considerably shortened half-life compared with vector-only control in a pulse-chase analysis (pK3 < 40 min, vector = >120 min). We also observed that very little MHCI in the pK3-expressing cells gained endoglycosidase H (Endo-H) resistance, suggesting that pK3 is targeting nascent MHCI for degradation. Either ERAD or lysosomal degradation pathways have been implicated in the destruction of substrates targeted by vMARCH ligases studied thus far. For example, the vMARCH ligases kK3 and kK5 down-regulate their respective substrates from the cell surface via endocytosis followed by their targeting to the lysosome for destruction (11–13, 34). In contrast, mK3 targets newly synthesized MHCI for destruction via ERAD (5, 8). To determine which degradation pathway pK3 utilizes to facilitate the destruction of MHCI, pK3-expressing cells were treated with different pharmacologic inhibitors that block either proteasomal- or lysosomal-mediated degradation. As shown in supplemental Fig. 3, 2-h treatment with the proteasomal inhibitors MG-132 (30 μm) or epoxomicin (10 μm) stabilized MHCI protein levels compared with controls. However, no stabilization of MHCI was observed when pK3-expressing cells were treated with the lysosomal degradation pathway inhibitors NH4Cl (50 mm) or bafilomycin A1 (2 μm). To extend these initial results we metabolically labeled murine fibroblasts expressing pK3 that had been treated with either DMSO, MG-132 (50 μm), or epoxomicin (20 μm) and measured the amount of MHCI at multiple points over a 2-h time course (Fig. 2B). Both proteasomal inhibitors dramatically increased the stability of MHCI in the presence of pK3. These data demonstrate that pK3, like mK3, induces ERAD of nascent MHCI.

FIGURE 2.

pK3 induces ERAD of nascent MHCI. A, B6/WT3 cells stably co-expressing Ld and either GFP alone (vector) or wt pK3 and GFP (pK3) were pulse-labeled with [35S]Cys/Met for 15 min and chased for the indicated times. After lysis with Nonidet P-40, Ld heavy chains were immunoprecipitated with mAbs 64-3-7 and 30-5-7, digested with Endo-H, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography (upper panel). Endo-H-resistant and -sensitive forms of Ld are indicated by an r and s, respectively. Relative band densities for Endo-H-resistant (upper right panel) and Endo-H-sensitive (lower right panel) Ld heavy chains are plotted in the lower panel as a function of chase time. Data shown in the lower panel represent replicates of two experiments, and the differences between the turnover of pK3 versus vector are significant at p < 0.01(**) in an unpaired t test at the 30, 60, and 120 time points. B, B6/WT3 cells stably co-expressing Ld and wt pK3 were treated with either DMSO, 50 μm MG-132, or 20 μm epoxomicin for 3 h before pulse labeling with [35S]Cys/Met for 15 min and were chased in the presence of the inhibitors for the indicated times. Ld heavy chains were immunoprecipitated as above, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. Relative band densities of Ld heavy chains from gels are plotted as percentage of the intensity at time zero for each sample (lower panel).

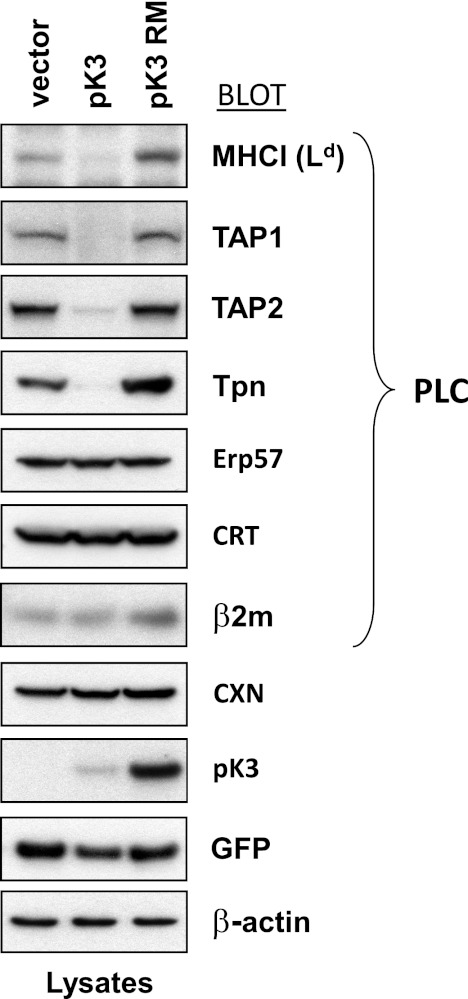

pK3 Destabilizes Membrane-bound Components of PLC

Interestingly, in certain cell lines mK3 has also been reported to destabilize TAP (particularly TAP2) and to a lesser extent, Tpn (35). Because pK3 appears to also target nascent MHCI, we wanted to determine whether pK3 targeted the degradation of components of the PLC (i.e. TAP1, TAP2, Tpn, Erp57, and CRT). To address this question, we stably expressed pK3, pK3 RM, or vector only along with GFP in murine fibroblasts. Steady state levels of the PLC constituents were then compared by immunoblotting (Fig. 3). As expected, we found that MHCI (Ld) was destabilized in the presence of pK3 but not in vector only or pK3 RM controls. In addition, the steady state levels of both subunits of TAP as well as Tpn were dramatically decreased compared with controls. However, soluble members of the PLC (Erp57, CRT, and β2m) as well as the ER chaperone calnexin were all unaffected by the presence of pK3. Additionally, pK3 was found to be more than three times less stable than the non-catalytic pK3 RM form (Fig. 3). This finding suggests that pK3 may auto-ubiquitinate and down-regulate itself in a RING-dependent manner.

FIGURE 3.

pK3 destabilizes membrane-bound components of the PLC. B6/WT3-Ld cells stably expressing/co-expressing either GFP alone (vector) or GFP and wt pK3 (pK3), or GFP and pK3 RM (pK3 RM) were Nonidet P-40 lysed and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Lysates were probed with peptide loading complex component and ER chaperone-specific antibodies. β-Actin, GFP, and pK3 blots were included as loading and expression controls.

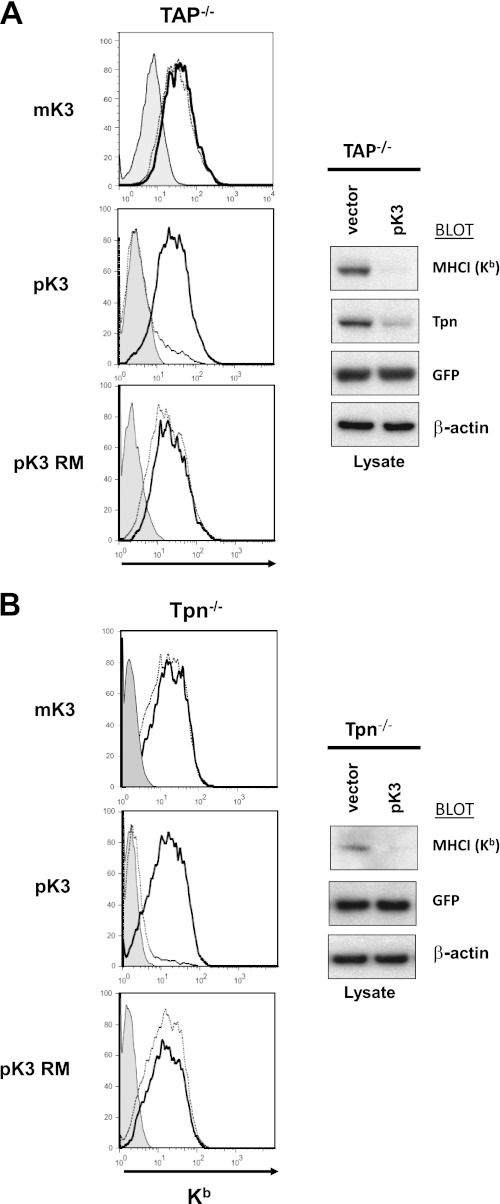

Destabilization of MHCI by pK3 Is Independent of TAP and Tpn

To determine whether pK3 requires TAP or Tpn for destabilization of MHCI proteins, pK3 was expressed in murine cell lines that lacked either TAP1 (FT1−) or Tpn (Tpn−/−). As shown in Fig. 4A, pK3 was still capable of down-regulating MHCI from the surface of cells lacking TAP. Expression of pK3 in FT1− cells also led to a dramatic reduction in the steady state levels of not only MHCI, but Tpn. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4B, cells lacking Tpn were still capable of down-regulating steady state levels and surface expression of MHCI proteins. Thus, destabilization of MHCI proteins by pK3 is independent of TAP and Tpn. It should also be noted TAP is known to be markedly destabilized in cells lacking Tpn; thus, the potential of pK3-induced destabilization of TAP could not be assessed in this experiment. In any case, the ability of pK3 to down-regulate MHCI in the absence of TAP and Tpn clearly distinguishes its mechanism of substrate recognition from that of mK3 (7).

FIGURE 4.

Destabilization of MHCI by pK3 is independent of TAP and Tpn. A, surface expression of MHCI (Kb) was monitored in FT1− murine fibroblasts which lack TAP1 (TAP−/−). Surface staining of GFP positive (mK3, pK3, or pK3 RM-transduced) and GFP negative (non-transduced) are represented by open dotted lines and open bold line histograms, respectively, and shaded histograms represent negative control antibody staining (left). Nonidet P-40 lysates from FT1− (TAP−/−) cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-Kb, -Tpn, -GFP, and -βactin (right). B, surface expression of MHCI (Kb) was monitored in murine fibroblasts lacking Tpn (Tpn−/−). Surface staining of GFP positive (mK3, pK3, or pK3 RM transduced) and GFP negative (non-transduced) are represented by open dotted lines and open bold line histograms, respectively, and shaded histograms represent control antibody staining (left). Nonidet P-40 lysates from Tpn−/− cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-Kb, -GFP, and -β-actin (right).

Nascent MHCI Is Primary Binding Partner of pK3

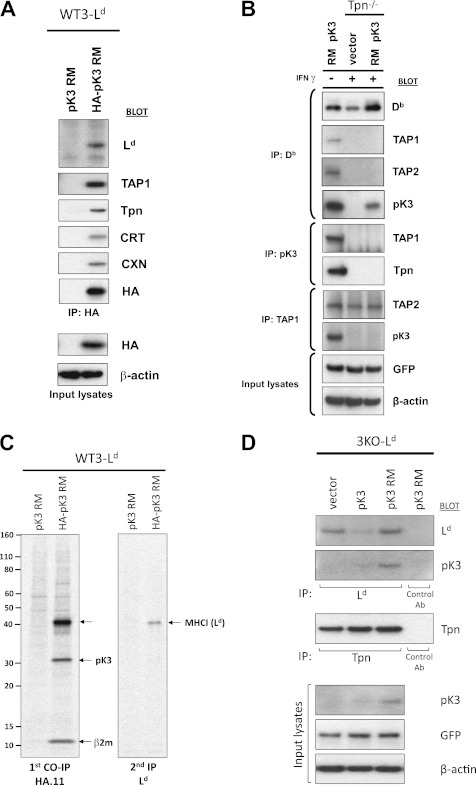

To probe potential binding partners of pK3, we assessed physical association by IP and Western blotting. For these experiments we used the catalytically inactive pK3 RM to prevent destabilization of MHCI, TAP, and Tpn. As shown in Fig. 5A, HA-tagged pK3 RM expressed in WT3-Ld cells was associated with MHCI as well as components of the PLC. More informatively, physical association was also tested in Tpn−/− cells as Tpn is known to be required for physical association of MHCI with TAP (36). In Tpn−/− cells the pK3 RM no longer associates with TAP but did retain physical association with MHCI (Fig. 5B). Thus, pK3 is capable of physical association with MHCI proteins in the absence of TAP/Tpn, and the association of pK3 with the PLC is likely indirect.

FIGURE 5.

Nascent MHCI is the primary binding partner of pK3. A, B6/WT3 stably co-expressing Ld and either an untagged pK3 RM (pK3 RM) or an N-terminally HA-tagged pK3 RM were digitonin-lysed, co-immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with antibodies to components of the PLC and ER chaperones. Input lysates probed with anti-HA and -β-actin are shown below as expression and loading controls. B, B6/WT3 and Tpn−/− murine fibroblasts (both H-2b) were left untreated or treated with IFN-γ (125 units/ml for 24 h) as indicated before harvest. Cells were digitonin-lysed, co-immunoprecipitated with either anti-Db (28–14-8), -pK3, or -TAP1 antibodies, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with antibodies to components of the PLC and pK3. Input lysates probed with anti-GFP, and -β-actin are shown below as expression and loading controls. C, murine fibroblasts (WT3-Ld) expressing either a pK3 RM or a HA-pK3 RM were pulse-labeled with [35S]Cys/Met for 1 h, lysed with digitonin, and co-immunoprecipitated using HA.11 mAb, and precipitates were eluted by incubation in 0.5% SDS and 10 mm DTT at room temperature for 10 min followed by boiling for 10 min. A fraction of this eluate was resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography (left panel), and the rest was subjected to reprecipitation with a conformation-independent anti-Ld mAb 64-3-7 (right panel). D, murine fibroblasts lacking endogenous MHCIa and β2m but stably expressing exogenous Ld (3KO-Ld) and either GFP alone (vector), GFP and wt pK3 (pK3), or GFP and pK3 RM (pK3 RM) were digitonin-lysed and co-immunoprecipitated with either anti-Ld mAbs (64-3-7 and 30-5-7), anti-Tpn Ab (Ra-2669), or control preimmune/isotype control Abs. Immunoprecipitates were eluted, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with anti-Ld, -pK3, and -Tpn antibodies. Input lysates were probed with anti-pK3, -GFP, and -β-actin and are shown below as expression and loading controls.

To gain an unbiased view of which protein(s) is predominantly detected in physical association with pK3, we immunoprecipitated an HA-tagged pK3 RM from a digitonin lysate of metabolically labeled murine fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 5C, left panel, in addition to the strong band at ∼31 kDa corresponding to the HA-tagged pK3 RM, there were only two other major bands not present in the co-immunoprecipitation control. These bands migrated at ∼42 and ∼12 kDa and corresponded to the expected molecular masses of MHCI and β2m, respectively. A fraction of the eluate from the initial co-immunoprecipitation was denatured and reimmunoprecipitated using a conformation-independent anti-Ld antibody to confirm that the 42-kDa band was indeed MHCI (Fig. 5C, right panel). Together these data provide strong evidence that MHCI is the primary binding partner of pK3 viral ligase.

To determine whether physical association of pK3 with MHCI is β2m-dependent, we tested whether the pK3 RM could be found in physical association with MHCI in a cell line that lacks β2m. Interestingly, both the physical association between the pK3 RM and MHCI (Ld) and the ability of pK3 to destabilize MHCI were retained in the absence of β2m (Fig. 5D). We next wanted to address whether pK3 could discriminate between peptide bound and non-peptide bond forms of β2m-assembled MHCI. To test peptide dependence, mAbs that can distinguish peptide-folded (30-5-7) and unfolded (64-3-7) conformers of mouse Ld were used. As shown in supplemental Fig. S4, pK3 was detected in physical association with both peptide folded and unfolded forms of Ld. This result was consistent with the aforementioned detection of pK3 in association with PLC components (Fig. 5A). However, physiologically, the fact that pK3 potently down-regulated TAP/Tpn likely minimizes the opportunities for pK3 to interact with peptide associated MHCI proteins. However, regarding substrate specificity, these combined results indicate that pK3 can associate with MHCI heavy chains regardless of their assembly with β2m or peptide.

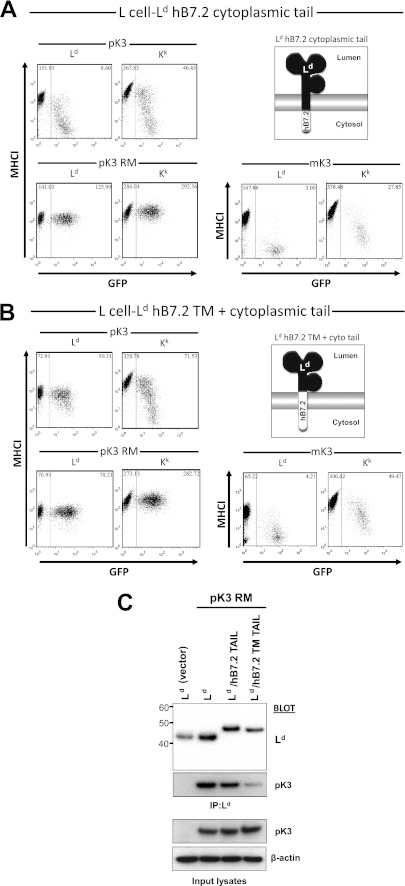

pK3 Function and Physical Association with MHCI Requires Interaction with Its TM Domain

We next investigated which MHCI domains interacted with pK3. Because pK3 is predicted to have only 12 lumenal amino acids and it can bind MHCI regardless of its assembly with β2m or peptide, it was considered most likely that pK3 associates with cytosolic and/or TM domains of nascent MHCI. To functionally test whether the recognition of the cytoplasmic domain of MHCI was required for regulation by pK3, a surface chimeric Ld molecule in which the cytoplasmic tail was substituted with the cytoplasmic tail from huB7.2 (Ld/hB7.2 TAIL) was tested in cells also expressing pK3 or pK3 RM. As shown in Fig. 6A, this chimeric molecule was still efficiently down-regulated by pK3 in a RING-dependent manner. To extend these findings, we next tested the second MHCI chimera in which both the cytoplasmic and TM domains of Ld were replaced with the corresponding domains of huB7.2 (Ld/hB7.2 TM-TAIL). Interestingly, pK3 did not efficiently down-regulate the Ld/B7.2 TM-TAIL chimera from the surface of the same cells even though endogenous MHCI Kk was down-regulated (Fig. 6B). These functional data reveal that the TM domain, but not the cytoplasmic tail of MHCI, is required for pK3-mediated down-regulation from the cell surface. To test whether the TM domain of MHCI is also necessary for physical interaction with pK3, these same chimeric Ld/hB7.2 molecules were tested by IP followed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 6C, much less pK3 RM coprecipitated with the Ld/hB7.2 TM TAIL molecules than with the Ld/hB7.2 TM chimera or intact Ld (Fig. 6C). The small amount of pK3 RM that did coprecipitate with the Ld/hB7.2 TM TAIL is likely explained by the multimeric nature of MHCI binding to TAP (37). In any case, these combined data suggest that pK3 directly binds the TM domain of MHCI to down-regulate MHCI surface expression. By contrast, mK3 does not require the MHCI TM or cytoplasmic tail, as its substrate specificity is conferred by binding the PLC (7, 38).

FIGURE 6.

pK3 function and physical association with MHCI requires interaction with its TM domain. A, L cell (H-2k) murine fibroblasts stably expressing a chimeric Ld molecule in which the cytoplasmic tail of Ld was replaced with cytoplasmic tail from huB7.2 (L cell-Ld hB7.2 cytoplasmic tail; left) were transduced with either pMIG-pK3 (pK3), pMIG-pK3 RM (pK3 RM), or pMIG-mK3 (mK3). Surface expression of murine MHCI alleles (y axis) versus GFP fluorescence (x axis) was monitored. The GFP+ (right boxes) and GFP− populations (left boxes) in each cell line represent the pMIG transduced and non-transduced cells, respectively. The numbers in the upper corners of both sections of each plot represent the median level of surface MHCI staining on the population within the box. B, L cell (H-2k) murine fibroblasts stably expressing a chimeric Ld molecule, in which the TM domain and cytoplasmic tail of Ld was replaced with TM domain and cytoplasmic tail from huB7.2 (L cell-Ld hB7.2 TM+ cyto tail; left) were transduced with either pMIG-pK3 (pK3), pMIG-pK3 RM (pK3 RM), or pMIG-mK3 (mK3). Surface expression of murine MHCI alleles (y axis) versus GFP fluorescence (x axis) was monitored. The GFP+ (right boxes) and GFP− populations (left boxes) in each cell line represent the pMIG transduced and non-transduced cells respectively. The numbers in the upper corners of both sections of each plot represent the median level of surface MHCI staining on the population within the box. C, L cells stably co-expressing either Ld, Ld hB7.2 cytoplasmic tail, or Ld hB7.2 TM+ cyto tail and either GFP alone (vector) or GFP and pK3 RM (pK3 RM) were digitonin-lysed and co-immunoprecipitated with anti-Ld mAbs (64-3-7 and 30-5-7). Immunoprecipitates were eluted, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with anti-Ld and -pK3 antibodies. Input lysates probed with anti-pK3 and -β-actin are shown below as expression and loading controls.

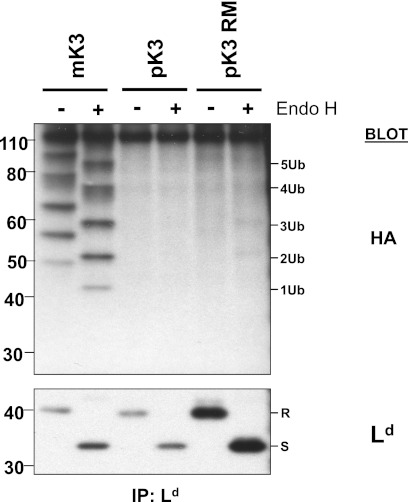

pK3 Does Not Detectably Ubiquitinate MHCI Proteins

We next wanted to determine whether MHCI proteins were ubiquitinated. Substrate ubiquitination was predicted based on homology of pK3 to other MARCH E3 ligases, in vitro E3 ligase activity of pK3, and the rapid turnover of MHCI in the presence of pK3. Furthermore, because pK3-mediated destabilization of MHCI is TAP- and Tpn-independent, we considered MHCI the most likely substrate of pK3. We first used two functional assays to test whether the cytosolic tail of MHCI was ubiquitinated by pK3. Because vMARCH ligases are known to be capable of both lysine and non-lysine ubiquitination, we measured surface levels of an Ld molecule lacking all cytosolic Lys, Cys, Ser, and Thr residues (Ld-KCST-less). To our surprise we found that pK3 was still able to potently down-regulate the Ld-KCST-less molecule from the surface of cells (supplemental Fig. S5, left). We also measured whether an MHCI molecule with a minimal cytoplasmic tail required for proper membrane insertion (Ld-TM-MRRRRNT) could be destabilized by pK3. Interestingly, in these cells both TAP and Tpn levels were reduced, and the tail-less MHCI molecule was potently down-regulated (supplemental Fig. S5, right).

To determine whether pK3 could be ubiquitinating non-tail residues of MHCI proteins, cells were treated with a proteasome inhibitor for 3 h and semi-permeabilized to remove cytosolic proteins including endogenous ubiquitin. These cells were then incubated with HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub), deubiquitinase inhibitor, and Fraction II of rabbit reticulocyte extract containing E1 and most E2s in the presence of an ATP regenerating system. After 45 min, MHCI molecules from semipermeabilized cells expressing either pK3, pK3 RM, or mK3 were immunoprecipitated, electrophoresed, and blotted with anti-HA. As shown in Fig. 7, there was a striking absence of pK3-mediated ubiquitination of MHCI, whereas substantial levels of mK3-mediated ubiquitination were observed as expected. Similarly, after extensive investigation, we have also failed to observe pK3-induced ubiquitination of Tpn or TAP using intact cells (not shown). Although striking in comparison with other vMARCH proteins, there are several examples in the literature where the ubiquitin proteasome system has been implicated, but no ubiquitin conjugation of substrates has been detected due to rapid reversal by deubiquitinases (39). Although speculative, we propose that pK3 may auto-ubiquitinate when it binds its primary binding partner HC as has been reported for several other E3 ligases (40, 41). This model is supported by our findings that pK3 and HC are both degraded in a RING-dependent manner and with the same kinetics (see below), and the tail of HC is not ubiquitinated or required (supplemental Fig. S 5). Thus, when pK3 is bound to tailless HC, only the N- and C-terminal portions of pK3 provide access to the ubiquitin proteasome system in the cytosol for dislocation and degradation.

FIGURE 7.

Failure to detect pK3-mediated ubiquitination of MHCI proteins. Murine fibroblasts co-expressing Ld and either mK3, pK3, or pK3 RM were treated with 20 μm epoxomicin for 3 h and semi-permeabilized, and the membrane fraction was incubated for 45 m with HA-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) in the presence of Fraction II, deubiquitinase inhibitor, and an ATP regenerating system. The semi-permeabilized cells were digitonin-lysed and co-immunoprecipitated with anti-Ld mAbs (64-3-7 and 30-5-7). Immunoprecipitates were eluted, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with anti-HA and -Ld antibodies. Endo-H-resistant and -sensitive forms of Ld are indicated by a R and S, respectively.

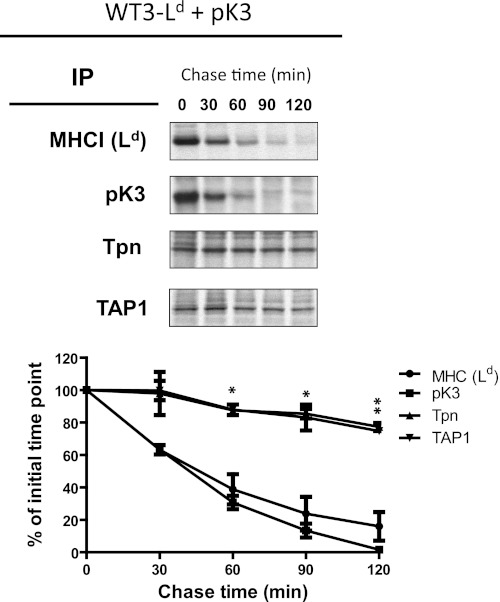

Loss of Nascent MHCI Leads to Secondary Destabilization of Tpn and TAP

To further probe the mechanism of pK3-induced substrate down-regulation, we next wanted to determine whether pK3-induced destabilization of MHCI, Tpn, TAP, and itself were temporally discrete or linked events. To examine this, murine fibroblasts expressing pK3 were metabolically labeled, and the kinetics of the turnover of MHCI, pK3, Tpn, and TAP were monitored by pulse-chase analysis (Fig. 8). Interestingly, distinct differences in the stability of these molecules were detected. More specifically, whereas pK3 and MHCI displayed similar and very rapid degradation kinetics, both Tpn and TAP were stable for a much longer period of time. These data suggest that the degradation of MHCI and pK3 may be a linked event and that the destabilization of Tpn and TAP may be a secondary event. To experimentally test this hypothesis, we assessed steady state levels of MHCI and Tpn in a cell line that lacked β2m (3KO-Ld). The rationale for choosing these cells was that in the absence of β2m, MHCI cannot associate with and stabilize the PLC. Therefore, if the destabilization of Tpn/TAP is a secondary event due to the loss of MHCI facilitated by pK3, one would expect steady state levels of Tpn to be unaffected by pK3 in β2m-deficient cells. Indeed, we found that whereas pK3 dramatically destabilized MHCI in the absence of β2m, steady state levels of Tpn were unaffected (Fig. 5D). These results reveal that the destabilization of Tpn and TAP is secondary to the loss of pK3-facilitated destabilization of MHCI and suggest that the stability of MHCI and Tpn/TAP is linked.

FIGURE 8.

Loss of nascent MHCI leads to the secondary destabilization of Tpn and TAP. B6/WT3 cells stably co-expressing Ld and wt pK3 were pulse-labeled with [35S]Cys/Met for 15 min and chased for the indicated times. Ld heavy chains, pK3, Tpn, and TAP1 were immunoprecipitated, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. Relative band densities of Ld heavy chains, pK3, Tpn, and TAP1 from gels are plotted as the percentage of the intensity at time 0 for each sample (lower panel). Data shown in the lower panel represent replicates from two independent experiments. Bonferroni's multiple comparison test showed that MHC(Ld) or pK3 versus Tpn or TAP are significantly different at 60, 90, and 120 min (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01), whereas Tpn versus TAP and MHC (Ld) versus pK3 comparisons showed no significant differences at any time point.

These cumulative findings support the model that the destabilization of Tpn and TAP results from the absence of MHCI in cells expressing pK3. More specifically, in cells with reduced MHCI levels due to pK3-facilitated degradation, the lack of MHCI could destabilize Tpn, which in turn would lead to the destabilization of TAP. Support for this premise comes from observations that (i) MHCI degradation by pK3 is independent of TAP/Tpn, (ii) MHCI degradation is considerably more rapid than TAP/Tpn, (iii) Tpn is stable in the presence of pK3 when Tpn is not associated with MHCI (Fig. 5D), and (iv) Tpn-deficient mouse cells are known to have dramatically reduced levels of TAP (42–45). In total, our data support the model that pK3 directly interacts with MHCI through its TM domain, auto-ubiquitinates, and dislocates itself along with MHCI heavy chains, and this event destabilizes TAP/Tpn, which are degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. S6).

DISCUSSION

We report here that viral ligase pK3 of RHVP, like its previously described homologs mK3 of γHV68 and kK3/kK5 of KSHV, regulates MHCI protein expression. However, each of these viral ligases has a distinct collection of substrates in addition to classical MHCI proteins. Also, there are important mechanistic differences in substrate recognition by mK3, kK3, and kK5, some of which can now be explained by recruited cellular proteins (1, 19). Perhaps the most intriguing similarities and differences are between pK3 and mK3. Both of these viral ligases target ERAD of MHCI proteins. However, the primary binding partners for mK3 are TAP/Tpn (7). Indeed, TAP/Tpn appear to function as an adaptor complex that juxtaposes the RING-CH domain of mK3 in the proximity of the cytoplasmic tail of MHCI HCs when they enter the peptide loading complex to acquire a suitable peptide (26, 38, 46).

In contrast to TAP being the primary binding partner for mK3, the primary binding partner of pK3 is HC. This conclusion is supported by the observations that (i) pK3 only regulates mouse class I even when expressed in human cells, (ii) pK3 is stabilized in cells that also express MHCI, (iii) HC and β2m are the predominant proteins that co-IP with pK3, and (iv) pK3 associates with and destabilizes MHCI in the absence of β2m. Furthermore, pK3-mediated degradation of MHCI proteins is TAP/Tpn-independent, whereas mK3-mediated degradation of MHCI proteins requires both TAP and Tpn. Interestingly, both mK3- and pK3-expressing cells have greatly reduced levels of MHCI; however, unlike pK3, it is known that mK3 remains quite stable and has been shown to associate with the TAP/Tpn complex even in the absence of MHCI (7). The direct association of mK3 with TAP/Tpn not only serves to provide substrate specificity but may also result in the partial stabilization of the PLC when levels of MHCI are greatly reduced.

We also show here that the TM domain of HC is critical for pK3 binding and the induction of ERAD. Although mK3 interaction with MHCI as mentioned above is dependent upon its RING proximity to the HC tail, interaction of KSHV ligase kK3 with MHCI was found to be TM-dependent (9). Mechanistically, it is highly intriguing how pK3 specifically detects HCs in a TM-dependent manner. Relevant to this question, a recent report by Hampton and co-workers (47) showed that the RING-H2 bearing Hrd1p ligase of yeast uses its TM domain to specifically detect misfolded membrane proteins. The model they propose is that Hrd1p distinguishes substrates based on hydrophilic residues in their respective TM domains and that exposed hydrophilic residues of the substrate can reflect the folding state of the substrate. Such a model would be analogous to how misfolded aqueous proteins are detected by ER chaperone proteins using hydrophobic interactions (48, 49). In a related study, Kreft and Hochstrasser (50) discovered that an unusual TM helix of Doa10, a yeast RING-CH E3 ligase, is highly sensitive to mutation and critical for controlling the ERAD of its cognate E2 enzyme. Thus, recent studies of Hrd1p and Doa10, both evolutionarily conserved ERAD-associated ligases, establish the importance of the TM domains of E3s in ERAD substrate recognition. However, these two cellular ligases also appear to use disparate mechanisms, making future chemical and structural definition of the specific interaction of pK3 and MHCI of considerable interest. Because E3 ligases may directly function as ER membrane components of a channel (51), TM interaction between ligase and substrate may promote the initiation of dislocation events.

In addition to their difference in primary binding partners, the mechanism of HC ubiquitination by mK3 versus pK3 appears dramatically different. Whereas mK3-induced degradation requires ubiquitination sites in the HC tail, pK3-induced degradation does not require Lys, Cys, Ser, or Thr potential ubiquitination sites in the HC tail or even a HC tail. Furthermore, mK3-mediated ubiquitin conjugation of HC is readily apparent in IP/Western blot experiments, but we have yet to detect HC ubiquitination in pK3-expressing cells (Fig. 7). However, the degradation of pK3 and HC are both dependent upon catalytically active pK3 and the degradation kinetics of pK3 and HC are indistinguishable. In addition, as mentioned above, the tail of HC is not required for degradation; thus, in the pK3-HC complex only the N and C domains of pK3 are exposed to the cytosol. Accordingly, we propose the model that pK3 auto-ubiquitinates when it binds HC, perhaps resulting from an HC-induced juxtaposition of the N and C cytosolic domains of pK3. Upon ubiquitination, pK3 would then extract the pK3-HC complex from the ER into the cytosol for degradation by the proteasome. Interestingly, interaction of the N and C domains of kK3 and kK5 has also been implicated in facilitating the ubiquitination of HC molecules (52), and these authors speculated that such interaction may position the E2 with substrate residues to be ubiquitin-conjugated. Furthermore, there are now several examples of physiologically important auto-ubiquitination by cellular E3 ligases including the prototypic ERAD-associated ligase gp78 that regulates its own degradation in a RING-dependent manner (40). In any case all indications are that the pK3 uses a ubiquitin proteasome system-dependent mechanism to induce the ERAD of MHCI proteins, and its specific mechanisms of substrate recognition and dislocation are clearly unique compared with other MARCH ligases studied thus far. Thus, there is little doubt that future comparisons of MARCH ligases, particularly pK3 and mK3, will yield valuable insights.

Our findings with pK3 also provide a critical insight into the dependence of PLC stabilization on the presence of HC/β2m complexes. In an early characterization of mK3 Boname et al. (35) noted that mK3 not only destabilizes HC but in certain cell lines it also destabilizes Tpn and TAP (particularly TAP2). Also, the degradation of TAP was mK3 RING-CH-dependent, although ubiquitin conjugation of TAP was not detected. Based on these findings it was proposed that this was an attack of mK3 on the PLC that broadened the inhibitory repertoire of mK3 to include HCs without tail ubiquitination sites (e.g. Qa-2). In addition, by also regulating TAP/Tpn expression, it was proposed that mK3 was adjusting its own expression to the level of antigen presentation. Curiously, even though pK3 and mK3 have different primary binding partners and different mechanisms of substrate ubiquitination, they both have the ability to destabilize TAP/Tpn. We present evidence here that TAP/Tpn destabilization is likely a secondary effect of class I removal and that this secondary destabilization is not dependent upon the enzyme activity of the viral ligase. In support of this conclusion, TAP is known to be very unstable in the absence of Tpn even without expression of immune evasion proteins (42–45). Furthermore, mK3 is very unstable in the absence of its primary binding partner TAP, and this instability is RING-CH-independent (7, 35). Additionally, in the presence of pK3 or mK3, the degradation of TAP and Tpn is kinetically much slower than that of MHCI proteins (Fig. 8 and Ref. 35), and Tpn is not destabilized by pK3 when Tpn does not bind MHCI (Fig. 5D). Thus, the instabilities of mK3 and pK3 without their primary binding partners (TAP and HC, respectively) as well as the instabilities of TAP/Tpn in the absence of MHCI proteins likely reflect cellular mechanisms of ER quality control of membrane proteins in elimination of unpaired binding partners. In any case our findings establish that there is a physiological co-dependence of MHCI and PLC quality control. Interestingly, we found that it is only the integral membrane components of the PLC, TAP, and Tpn that are dependent upon MHCI expression. Consistently, the TM domain of Tpn is known to be important for both its interaction with MHCI (45, 53, 54) and TAP (55). Although TM interactions are known to be important for the assembly of multimeric complexes such as the TCR-CD3 complex (56), our findings suggest TM interactions are also critical for monitoring the disassembly of MHC-PLC complexes and targeting them for ERAD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Wang for access to the RHVP sequence and Drs. Joyce C. Solheim, Laura C. Simone, and Janet M. Connolly for critical review and discussion.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by a National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI019687, R01 CA096511, and Project 3 of U54 AI057160. This work was also supported by the Midwest Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease Research.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- mK3

- E3 ligase from γherpesvirus 68

- γHV6

- γ-herpesvirus 68

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation

- β2m

- β2-microglobulin

- CRT

- calreticulin

- MARCH

- membrane-associated RING-CH proteins

- RM

- pK3 RING-CH mutant (C86G, C89G)

- vMARCH

- viral MARCH

- MHCI

- class I major histocompatibility protein

- pK3

- E3 ligase from rodent herpesvirus Peru

- PLC

- peptide loading complex

- RHVP

- rodent herpesvirus Peru

- TAP

- transporter-associated with antigen processing

- Tpn

- tapasin

- TM

- transmembrane

- KSHV

- Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus Endo-H, endoglycosidase H

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- HC

- heavy chains

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HA

- human influenza hemagglutinin epitope.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lehner P. J., Hoer S., Dodd R., Duncan L. M. (2005) Down-regulation of cell surface receptors by the K3 family of viral and cellular ubiquitin E3 ligases. Immunol. Rev. 207, 112–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ohmura-Hoshino M., Goto E., Matsuki Y., Aoki M., Mito M., Uematsu M., Hotta H., Ishido S. (2006) A novel family of membrane-bound E3 ubiquitin ligases. J. Biochem. 140, 147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coscoy L., Ganem D. (2003) PHD domains and E3 ubiquitin ligases. Viruses make the connection. Trends Cell Biol. 13, 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Früh K., Bartee E., Gouveia K., Mansouri M. (2002) Immune evasion by a novel family of viral PHD/LAP-finger proteins of γ-2 herpesviruses and poxviruses. Virus Res. 88, 55–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boname J. M., Stevenson P. G. (2001) MHC class I ubiquitination by a viral PHD/LAP finger protein. Immunity 15, 627–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanchez D. J., Coscoy L., Ganem D. (2002) Functional organization of MIR2, a novel viral regulator of selective endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6124–6130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lybarger L., Wang X., Harris M. R., Virgin H. W., 4th, Hansen T. H. (2003) Virus subversion of the MHC class I peptide-loading complex. Immunity 18, 121–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu Y. Y., Harris M. R., Lybarger L., Kimpler L. A., Myers N. B., Virgin H. W., 4th, Hansen T. H. (2002) Physical association of the K3 protein of γ-2 herpesvirus 68 with major histocompatibility complex class I molecules with impaired peptide and β2-microglobulin assembly. J. Virol. 76, 2796–2803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coscoy L., Sanchez D. J., Ganem D. (2001) A novel class of herpesvirus-encoded membrane-bound E3 ubiquitin ligases regulates endocytosis of proteins involved in immune recognition. J. Cell Biol. 155, 1265–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duncan L. M., Piper S., Dodd R. B., Saville M. K., Sanderson C. M., Luzio J. P., Lehner P. J. (2006) Lysine 63-linked ubiquitination is required for endolysosomal degradation of class I molecules. EMBO J. 25, 1635–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hewitt E. W., Duncan L., Mufti D., Baker J., Stevenson P. G., Lehner P. J. (2002) Ubiquitylation of MHC class I by the K3 viral protein signals internalization and TSG101-dependent degradation. EMBO J. 21, 2418–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishido S., Wang C., Lee B. S., Cohen G. B., Jung J. U. (2000) Down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 and K5 proteins. J. Virol. 74, 5300–5309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lorenzo M. E., Jung J. U., Ploegh H. L. (2002) Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 utilizes the ubiquitin-proteasome system in routing class major histocompatibility complexes to late endocytic compartments. J. Virol. 76, 5522–5531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanchez D. J., Gumperz J. E., Ganem D. (2005) Regulation of CD1d expression and function by a herpesvirus infection. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1369–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishido S., Choi J. K., Lee B. S., Wang C., DeMaria M., Johnson R. P., Cohen G. B., Jung J. U. (2000) Inhibition of natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K5 protein. Immunity 13, 365–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mansouri M., Douglas J., Rose P. P., Gouveia K., Thomas G., Means R. E., Moses A. V., Früh K. (2006) Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus K5 removes CD31/PECAM from endothelial cells. Blood 108, 1932–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas M., Boname J. M., Field S., Nejentsev S., Salio M., Cerundolo V., Wills M., Lehner P. J. (2008) Down-regulation of NKG2D and NKp80 ligands by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K5 protects against NK cell cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1656–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Q., Means R., Lang S., Jung J. U. (2007) Down-regulation of γ interferon receptor 1 by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 and K5. J. Virol. 81, 2117–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansen T. H., Bouvier M. (2009) MHC class I antigen presentation. Learning from viral evasion strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 503–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bartee E., Mansouri M., Hovey Nerenberg B. T., Gouveia K., Früh K. (2004) Down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class I by human ubiquitin ligases related to viral immune evasion proteins. J. Virol. 78, 1109–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang X., Herr R. A., Hansen T. (2008) Viral and cellular MARCH ubiquitin ligases and cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 18, 441–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishido S., Matsuki Y., Goto E., Kajikawa M., Ohmura-Hoshino M. (2010) MARCH-I, A new regulator of dendritic cell function. Mol. Cells 29, 229–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loh J., Zhao G., Nelson C. A., Coder P., Droit L., Handley S. A., Johnson L. S., Vachharajani P., Guzman H., Tesh R. B., Wang D., Fremont D. H., Virgin H. W. (2011) Identification and sequencing of a novel rodent Gammaherpesvirus that establishes acute and latent infection in laboratory mice. J. Virol. 85, 2642–2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crumpacker D. B., Alexander J., Cresswell P., Engelhard V. H. (1992) Role of endogenous peptides in murine allogenic cytotoxic T cell responses assessed using transfectants of the antigen-processing mutant 174xCEM.T2. J. Immunol. 148, 3004–3011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu Y. Y., Myers N. B., Hilbert C. M., Harris M. R., Balendiran G. K., Hansen T. H. (1999) Definition and transfer of a serological epitope specific for peptide-empty forms of MHC class I. Int. Immunol. 11, 1897–1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang X., Lybarger L., Connors R., Harris M. R., Hansen T. H. (2004) Model for the interaction of gammaherpesvirus 68 RING-CH finger protein mK3 with major histocompatibility complex class I and the peptide-loading complex. J. Virol. 78, 8673–8686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X., Herr R. A., Chua W. J., Lybarger L., Wiertz E. J., Hansen T. H. (2007) Ubiquitination of serine, threonine, or lysine residues on the cytoplasmic tail can induce ERAD of MHC-I by viral E3 ligase mK3. J. Cell Biol. 177, 613–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carreno B. M., Solheim J. C., Harris M., Stroynowski I., Connolly J. M., Hansen T. H. (1995) TAP associates with a unique class I conformation, whereas calnexin associates with multiple class I forms in mouse and man. J. Immunol. 155, 4726–4733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harris M. R., Lybarger L., Yu Y. Y., Myers N. B., Hansen T. H. (2001) Association of ERp57 with mouse MHC class I molecules is tapasin-dependent and mimics that of calreticulin and not calnexin. J. Immunol. 166, 6686–6692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith J. D., Solheim J. C., Carreno B. M., Hansen T. H. (1995) Characterization of class I MHC folding intermediates and their disparate interactions with peptide and β2-microglobulin. Mol. Immunol. 32, 531–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Myers N. B., Harris M. R., Connolly J. M., Lybarger L., Yu Y. Y., Hansen T. H. (2000) Kb, Kd, and Ld molecules share common tapasin dependencies as determined using a novel epitope tag. J. Immunol. 165, 5656–5663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith J. D., Myers N. B., Gorka J., Hansen T. H. (1993) Model for the in vivo assembly of nascent Ld class I molecules and for the expression of unfolded Ld molecules at the cell surface. J. Exp. Med. 178, 2035–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang X., Herr R. A., Rabelink M., Hoeben R. C., Wiertz E. J., Hansen T. H. (2009) Ube2j2 ubiquitinates hydroxylated amino acids on ER-associated degradation substrates. J. Cell Biol. 187, 655–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coscoy L., Ganem D. (2000) Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes two proteins that block cell surface display of MHC class I chains by enhancing their endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8051–8056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boname J. M., de Lima B. D., Lehner P. J., Stevenson P. G. (2004) Viral degradation of the MHC class I peptide loading complex. Immunity 20, 305–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sadasivan B., Lehner P. J., Ortmann B., Spies T., Cresswell P. (1996) Roles for calreticulin and a novel glycoprotein, tapasin, in the interaction of MHC class I molecules with TAP. Immunity 5, 103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ortmann B., Copeman J., Lehner P. J., Sadasivan B., Herberg J. A., Grandea A. G., Riddell S. R., Tampé R., Spies T., Trowsdale J., Cresswell P. (1997) A critical role for tapasin in the assembly and function of multimeric MHC class I-TAP complexes. Science 277, 1306–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang X., Connors R., Harris M. R., Hansen T. H., Lybarger L. (2005) Requirements for the selective degradation of endoplasmic reticulum-resident major histocompatibility complex class I proteins by the viral immune evasion molecule mK3. J. Virol. 79, 4099–4108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hjerpe R., Rodríguez M. S. (2008) Efficient approaches for characterizing ubiquitinated proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 823–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weissman A. M., Shabek N., Ciechanover A. (2011) The predator becomes the prey. Regulating the ubiquitin system by ubiquitylation and degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 605–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de Bie P., Ciechanover A. (2011) Ubiquitination of E3 ligases. Self-regulation of the ubiquitin system via proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1393–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garbi N., Tiwari N., Momburg F., Hämmerling G. J. (2003) A major role for tapasin as a stabilizer of the TAP peptide transporter and consequences for MHC class I expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 33, 264–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lehner P. J., Surman M. J., Cresswell P. (1998) Soluble tapasin restores MHC class I expression and function in the tapasin-negative cell line.220. Immunity 8, 221–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raghuraman G., Lapinski P. E., Raghavan M. (2002) Tapasin interacts with the membrane-spanning domains of both TAP subunits and enhances the structural stability of TAP1 x TAP2 Complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41786–41794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simone L. C., Wang X., Solheim J. C. (2009) A transmembrane tail. Interaction of tapasin with TAP and the MHC class I molecule. Mol. Immunol. 46, 2147–2150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Corcoran K., Wang X., Lybarger L. (2009) Adapter-mediated substrate selection for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 17475–17487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sato B. K., Schulz D., Do P. H., Hampton R. Y. (2009) Misfolded membrane proteins are specifically recognized by the transmembrane domain of the Hrd1p ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 34, 212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hirsch C., Jarosch E., Sommer T., Wolf D. H. (2004) Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. One model fits all? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695, 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vembar S. S., Brodsky J. L. (2008) One step at a time. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 944–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kreft S. G., Hochstrasser M. (2011) An unusual transmembrane helix in the endoplasmic reticulum ubiquitin ligase Doa10 modulates degradation of its cognate E2 enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20163–20174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bagola K., Mehnert M., Jarosch E., Sommer T. (2011) Protein dislocation from the ER. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 925–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cadwell K., Coscoy L. (2008) The specificities of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded E3 ubiquitin ligases are determined by the positions of lysine or cysteine residues within the intracytoplasmic domains of their targets. J. Virol. 82, 4184–4189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Petersen J. L., Hickman-Miller H. D., McIlhaney M. M., Vargas S. E., Purcell A. W., Hildebrand W. H., Solheim J. C. (2005) A charged amino acid residue in the transmembrane/cytoplasmic region of tapasin influences MHC class I assembly and maturation. J. Immunol. 174, 962–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Simone L. C., Wang X., Tuli A., McIlhaney M. M., Solheim J. C. (2009) Influence of the tapasin C terminus on the assembly of MHC class I allotypes. Immunogenetics 61, 43–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Papadopoulos M., Momburg F. (2007) Multiple residues in the transmembrane helix and connecting peptide of mouse tapasin stabilize the transporter associated with the antigen-processing TAP2 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9401–9410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Call M. E., Wucherpfennig K. W. (2005) The T cell receptor. Critical role of the membrane environment in receptor assembly and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 101–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Virgin H. W., 4th, Latreille P., Wamsley P., Hallsworth K., Weck K. E., Dal Canto A. J., Speck S. H. (1997) Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71, 5894–5904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.