Abstract

Background

Relapse to cocaine-seeking has been linked with low glutamate in the nucleus accumbens core (NAcore) causing potentiation of synaptic glutamate transmission from prefrontal cortex (PFC) afferents. Systemic N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been shown to restore glutamate homeostasis, reduce relapse to cocaine-seeking and depotentiate PFC-NAcore synapses. Here we examine the effects of NAC applied directly to the NAcore on relapse and neurotransmission in PFC-NAcore synapses, as well as the involvement of the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) mGluR2/3 and mGluR5.

Methods

Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine for 2 weeks and following extinction received either intra-accumbens NAC or systemic NAC 30 or 120 minutes, respectively, prior to inducing reinstatement with a conditioned cue or a combined cue and cocaine injection. We also recorded postsynaptic currents using in vitro whole cell recordings in acute slices and measured cystine and glutamate uptake in primary glial cultures.

Results

NAC microinjection into the NAcore inhibited the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. In slices, a low concentration of NAC reduced the amplitude of evoked glutamatergic synaptic currents in the NAcore in a mGluR2/3-dependent manner, while high doses of NAC increased amplitude in a mGluR5-dependent manner. Both effects depended on NAC uptake through cysteine transporters and activity of the cysteine/glutamate exchanger. Finally, we showed that by blocking mGluR5 the inhibition of cocaine-seeking by NAC was potentiated.

Conclusions

The effect of NAC on relapse to cocaine-seeking depends on the balance between stimulating mGluR2/3 and mGluR5 in the NAcore, and the efficacy of NAC can be improved by simultaneously inhibiting mGluR5.

Keywords: N-acetylcysteine, nucleus accumbens, cocaine, addiction, mGluR5, mGluR2/3

Introduction

Vulnerability to relapse is a cardinal feature of cocaine addiction, and the glutamatergic projection from the prefrontal cortex (PFC) to the nucleus accumbens core (NAcore) has been identified as a potentially important neural mediator of relapse (1,2). Accordingly, many enduring changes are produced in the physiology of this projection by the chronic administration of addictive drugs that have been used as a biological rationale in developing potential pharmacotherapies for treating addiction (3). A key observation along these lines is that withdrawal from chronic cocaine is associated with reduced nonsynaptic extracellular glutamate levels in the NAcore (2,4). Normally, extrasynaptic glutamate of glial origin negatively regulates synaptic glutamate release at PFC-NAcore synapses through activating presynaptic group II metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR2/3) (2). Reduced extrasynaptic glutamate after chronic cocaine is insufficient for normal mGluR2/3 activation, thereby increasing PFC-NAcore glutamate release probability (5).

A major contributor to the maintenance of extracellular glutamate in the NAcore is glial cystine/glutamate exchange (system Xc−), which exchanges extracellular cystine for intracellular glutamate (6). The cocaine-induced decrease in extracellular glutamate is associated with reduced system Xc− function (4,7) and reduced levels of its catalytic subunit, xCT (8). Hence, restoring nonsynaptic glutamate by targeting system Xc− has been evaluated as a pharmacotherapy in drug addiction. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a cystine prodrug that restores extracellular glutamate in the NAcore by stimulating system Xc− (4,7). NAC reduces desire for cocaine use (9) and the number of cigarettes smoked (10) in humans, and cocaine and heroin relapse in animal models (5,11,12). These effects are caused by NAC normalizing extrasynaptic glutamate levels that activate presynaptic mGluR2/3, and thereby reduce synaptic glutamate release (13) and cocaine- and heroin-seeking in animal models (14–16).

The use of NAC to inhibit drug-seeking by increasing nonsynaptic glutamate via activating system Xc− will restore tone onto other extrasynaptic glutamate receptors, in addition to mGluR2/3. This raises a potential paradox because restoring tone to mGluR5 should promote reinstatement of drug-seeking. Thus, mGluR5 stimulation with a positive allosteric modulator promotes, while inhibiting mGluR5 reduces the reinstatement of drug-seeking (17–21). Here we tested the hypotheses that NAC acts directly in the NAcore to reduce the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking and glutamate synaptic transmission in PFC-NAcore synapses, and that NAC acts via activating system Xc−. We then tested the hypothesis that NAC-mediated stimulation of mGluR2/3 and mGluR5 produces opposite effects on glutamate transmission, akin to the opposite effects on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Finally, having validated opposite effects of NAC-mediated stimulation of mGluR2/3 and mGluR5, we show that by blocking mGluR5 the behavioral efficacy of NAC to inhibit the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking is augmented.

Methods and Materials

Animal housing and surgery

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina approved all procedures. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250g) (Charles River Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were single housed under controlled temperature and humidity with a 12 hour light/dark cycle. All behavioral training occurred during the dark cycle. Rats were acclimated in the vivarium for one week prior to surgeries, and fed and watered ad libitum until 2 days before behavioral training, during which food was restricted to 4 pellets/day. Rats were anesthetized with ketamine HCl (87.5 mg/kg Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health) and xylazine (5 mg/kg Rompum, Bayer), and implanted with intravenous catheters. For microinjection experiments, rats were stereotaxically implanted with bilateral guide cannulas (26 gauge) aimed at NAcore according to Paxinos et al. (22) (+1.8mm anteroposterior, 1.5 mm mediolateral, and −5.5 mm dorsoventral from the skull surface). Intravenous catheters were flushed daily with cefazolin (0.2 ml of 0.1 gm/ml) and heparin (0.2 ml of 100 IU) to prevent infection and maintain catheter patency, and rats recovered for a week before behavioral training. Yoked saline controls received a noncontingent infusion of saline in parallel with cocaine rats receiving a self-administered infusion of cocaine.

Self-administration and extinction procedures

Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) in operant chambers with 2 retractable levers. The self-administration regimen consisted of 2 weeks (12 days) self-administration at >10 infusions/session. Daily sessions lasted 2 hours, with an active lever press resulting in 0.2 mg in 0.05 ml cocaine infusion (dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline) over 3 seconds, while inactive lever presses were of no consequence. A 5 sec cue tone (2900 Hz) and light followed each cocaine infusion. Cocaine infusions were also followed by a 20 second timeout during which active lever presses had no consequence.

Reinstatement of cocaine-seeking

After extinction training rats underwent a cocaine+cue-primed (10 mg/kg, i.p.) reinstatement trial. Following a counterbalanced crossover design, we microinjected 0.5 μl/side of aCSF or NAC (1 or 10 μg) at a rate of 0.25 μl/min 30 min prior to starting reinstatement trials (Figure 1B). In a second experiment NAC (10 μg/0.5 μl/side) was microinjected 30 min before cue-induced reinstatement (i.e., presenting the light and tone previously associated with cocaine infusion), and a systemic injection (1 mg/kg, i.p.) of (2S)-2-Amino-2-[(1S,2S)-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl]-3-(xanth-9-yl) propanoic acid (LY341495) was administered 5 min before NAC and 5 min before cue (Figure 1B). In a third experiment, cocaine-seeking was reinstated by a challenge injection of cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.). Two hours before cocaine, subjects were injected with NAC (10 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline vehicle, and 15 min prior to cocaine-primed drug-seeking rats were injected with saline or 3-((2-Methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MTEP; 1 mg/kg, i.p.) (Figure 6A). Each rat received a maximum of 3 reinstatement trials, and underwent 3 days of extinction training between each trial. The treatment order was randomized. Reinstatement testing lasted for 2 h and active lever presses were counted but resulted in no drug delivery. Although three different stimuli were used to initiate the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (e.g. cue, cocaine, or cue+cocaine), all have been shown to require activation of the projection from the PFC to the NAcore (2).

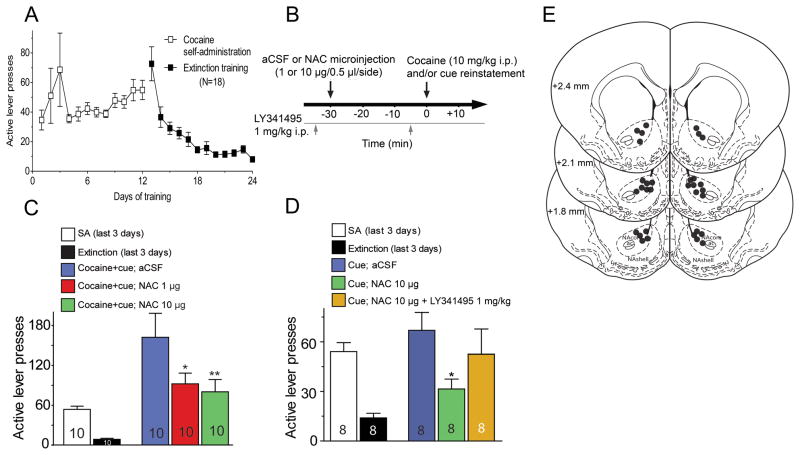

Figure 1.

Microinjection of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in the nucleus accumbens core inhibits cocaine-seeking reinstatement. (A) The training procedure included 2 weeks of cocaine self-administration (SA) followed by 2 weeks of extinction training. (B) Experimental paradigm for reinstatement testing. (C) Cocaine+cue-primed reinstatement was reduced by intra-accumbens NAC (1 or 10 μg/side). Data were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA with repeated measures (F(2,29)=6.48, p=0.008). (D) NAC (10 μg/side) inhibited cue-primed reinstatement, and was reversed by mGluR2/3 antagonist (LY341495, 1 mg/kg, i.p.). One-way repeated measures ANOVA, F(2,23)=3.74, p=0.050. (E) Illustration of cannula tips in the accumbens. mm are rostral to Bregma. * p<0.05 compared to microinjection of aCSF, using a Dunnett’s post hoc comparison to vehicle.

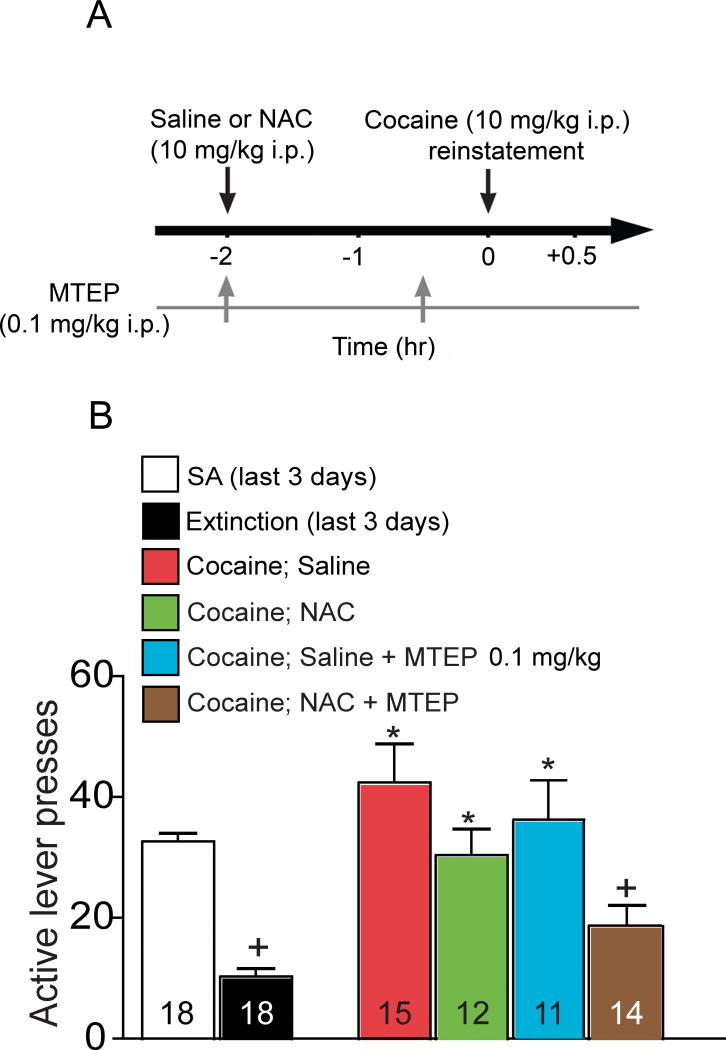

Figure 6.

Blocking mGluR5 with MTEP enhances the N-acetylcysteine (NAC)-induced inhibition of cocaine reinstatement. (A) Experimental paradigm for reinstatement testing. SA- self-administration (B) NAC (10 mg/kg, i.p.) reduced active lever presses following cocaine priming, while MTEP (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) had no effect. However, MTEP enhanced NAC-induced reduction in lever presses (F(4,69)= 9.23, p< 0.001). * p<0.05 compared to extinction, + p<0.05 compared to Sal+Sal, using a Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Slice preparation

Slices were prepared from saline-yoked or naïve animals. Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (see above) and decapitated. The brain was removed and coronal accumbens brain slices (220 μm) (VT1200S Leica vibratome) were collected into a vial containing aCSF (in mM: 126 NaCl, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 2.5 KCl, 2.0 NaPyruvate, 0.4 ascorbic acid, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2) and a mixture of 5 mM kynurenic acid and 50 μM D-(−)-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (D-AP5). Slices were incubated at 35°C for 30–40 minutes then stored at 25°C.

In vitro whole cell recording

All recordings were collected at 32°C (TC-344B, Warner Instrument Corporation) in the dorsomedial NAcore, where the prefrontal inputs are most dense (23,24), and where microinjections were localized (Figure 1E). Neurons were visualized with an Olympus BX51WI microscope. Inhibitory synaptic transmission was blocked with picrotoxin (50 μM). Multiclamp 700B (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) was used to record EPSCs under −80 mV voltage clamp whole cell configuration. Glass microelectrodes (1–2 MΩ) were filled with cesium based internal solution (in mM: 124 cesium methanesulfonate, 10 HEPES potassium, 1 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 10 NaCl, 2.0 MgATP, and 0.3 NaGTP, 1 QX-314, pH 7.2–7.3, 275 mOsm). Data were acquired at 10 kHz, and filtered at 2 kHz using AxoGraph × software (AxoGraph Scientific, Sydney). To evoke EPSCs, a bipolar stimulating electrode was placed ~100–200 μm dorsomedial of the recorded cell to maximize chances of stimulating PFC afferents. The stimulation intensity chosen evoked a ~50% of maximal EPSC. Each cell was superfused with a single concentration of NAC, cysteine, or cystine, since their effects were produced following uptake into cells and not washable. Recordings were collected every 30 sec and averaged over 1.5 min. Series resistance (Rs) measured with a 5 mV depolarizing step (10 ms) given with each stimulus and holding current were always monitored online. Recordings with unstable Rs, or when Rs exceeded 20 MΩ were aborted.

Primary cell culture

Primary cultures of astrocytes were prepared from cerebral cortices of 1- to 2-day-old rat pups (25). The tissue was dissociated and plated in 150 cm2 flasks at a density of 2.5×105 cells/ml. When the primary culture reached confluence, the monolayer of cells were trypsinized and plated into 12-well plates. Cells cultured for 21–35 days were used in the experiments. Uptake studies were performed in triplicate in bicarbonate buffered Krebs-Ringer solution (pH=7.4) (26). To isolate uptake via system Xc−, aspartate (1 mM) and acivicin (1 mM) were added into each well to block system XAG and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, respectively (27). Cystine uptake experiments were initiated by adding 0.5 μCi/ml of L-35S-cystine and incubating the culture for 15 min at room temperature. The uptake was terminated by rapidly washing the cells three times with ice-cold media. Cells were solubilized in 0.5 ml of RIPA buffer. Radioactivity and protein content in the cell lysate were measured. To control for possible effects of NAC to inhibit the reduction of 35S-cystine, some experiments were repeated using sodium-free 3H-glutamate uptake (250 nM, 51 Ci/mmol) to estimate the activity of system Xc− (28).

Statistics and histology

To determine cannula placement in the NAcore, animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, ip) followed by intra-cardiac perfusion of 10% formalin. Coronal slices (100 μm thick) were obtained and bilateral cannula location determined by an individual blind to the rats behavioral responses (22). Treatment groups and drug concentrations were compared using ANOVAs. For electrophysiological data and some behavioral data, within subjects measurements were made using a repeated measures ANOVA. A Bonferroni post-hoc test was employed for multiple comparisons between groups or a Dunnett’s t-test employed for multiple comparisons to a single control group.

Results

NAC in the NAcore inhibits the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking

To determine whether NAC acts in the NAcore to inhibit the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking we microinjected NAC into the NAcore of rats extinguished from cocaine self-administration (Figure 1A). Using a counterbalanced-crossover design, rats were microinjected with aCSF or NAC (1 or 10 μg/side) into the NAcore 30 min prior to initiating reinstatement by a combination of conditioned cue and cocaine injection (Figure 1B). Both doses of microinjected NAC reduced the reinstatement of lever pressing compared to microinjected aCSF (Figure 1C).

It was previously shown that pretreatment with systemic LY341495, a mGluR2/3 antagonist, prevents systemic NAC-mediated inhibition of cocaine reinstatement (29). Here we extend this finding and show (Figure 1D) that pretreatment with systemic LY341495 inhibited the capacity of NAC administered into the NAcore to reduce cue-induced lever pressing. Figure 1E shows the location of the microinjection sites in the NAcore.

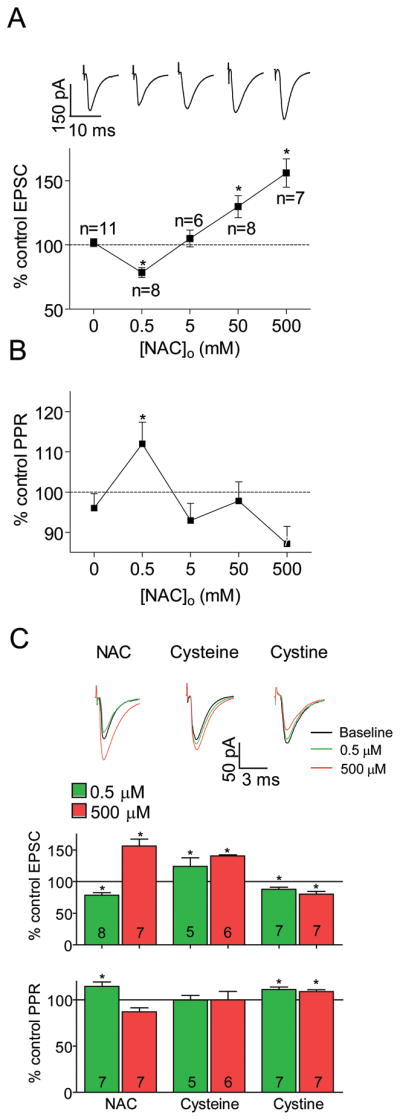

NAC has a biphasic effect on EPSCs in the NAcore

To examine the effect of NAC on neurotransmission in the NAcore we used whole cell patch recordings of spiny cells in acute slices from yoked-saline or drug-naïve rats. The application of a low dose of NAC (0.5 μM) resulted in a reduction in the EPSC amplitude (Figure 2A), consistent with previous data showing that cystine-induced activation of system Xc− increases nonsynaptic glutamate (4), which inhibits EPSC amplitude (29). However, the inhibitory effect of NAC reversed at higher concentrations, with 50 and 500 μM NAC significantly increasing EPSC amplitude. A change in paired pulse ratio (PPR) was employed as a marker of a presynaptic change in the efficacy of synaptic transmission (30,31). To reduce variability the PPR after NAC was divided by the PPR during baseline. PPR increased with 0.5 μM NAC, but no change was observed at other concentrations (Figure 2B), suggesting that the decrease in EPSC at 0.5 μM NAC involved a presynaptic mechanism, while the increase in EPSC at higher concentrations was more likely of postsynaptic origin.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent effect of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), cysteine, and cystine on neurotransmission in the NAcore. (A) Increasing NAC concentrations produced a biphasic effect on EPSC amplitude (■). Excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were normalized to baseline and are shown as mean percentage of baseline. Inset – representative traces illustrating the effect of NAC. Traces are from different cells, baseline EPSCs were normalized. One-way ANOVA F(4,39)=18.60, p<0.001. * p<0.05 using a Dunnett’s test comparing to 0. (B) Only 0.5 μM NAC changed the PPR. One-way ANOVA F(4,37)=4.95, p=0.003. * p<0.05 using a Dunnett’s test comparing to 0. (C) The effect of 0.5 (green) and 500 (red) μM NAC, cysteine or cystine on EPSC size (upper bars, compared to baseline EPSC) and PPR (bottom bars). NAC data are the same as in (A) and (B). Both 0.5 and 500 μM cysteine increased the EPSC (124 ± 13% and 141 ± 2%, respectively) but did not alter the PPR. Both 0.5 and 500 μM cystine inhibited the EPSC (88±3% and 80±5% respectively) and changed the PPR (111±3% and 109±2%, respectively). Inset - representative traces of a single cell for both concentrations of the same drug. * p<0.05 using a one- sample t-test compared to 100.

Two NAC derivatives, cysteine and cystine, have opposite effects on EPSCs

NAC is known to decompose to cysteine and then to cystine (32). Thus, its effect could be generated by one or both amino acids. Figure 2C shows that, akin to high concentrations of NAC, application of either 0.5 or 500 μM cysteine increased the EPSC amplitude. In contrast, both 0.5 and 500 μM cystine inhibited EPSC amplitude. Also, the PPR was insensitive to cysteine but was increased by both cystine concentrations. Thus, at 0.5 μM NAC acts more like cystine to inhibit the EPSC through a presynaptic mechanism, while at high doses NAC resembles the effect of cysteine to increase EPSC amplitude potentially via a postsynaptic mechanism.

NAC effect on EPSCs is blocked by CPG or BCH/Ser

The effects of NAC on EPSC amplitude are assumed to be mediated by increasing extracellular glutamate via activating system Xc−. To test this, we applied 0.5 or 500 μM NAC while blocking system Xc− with 10 μM (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine (CPG). CPG alone did not change EPSC amplitude. However, the capacity of 0.5 μM NAC to reduce and of 500 μM NAC to increase the EPSC was blocked by CPG (Figure 3).

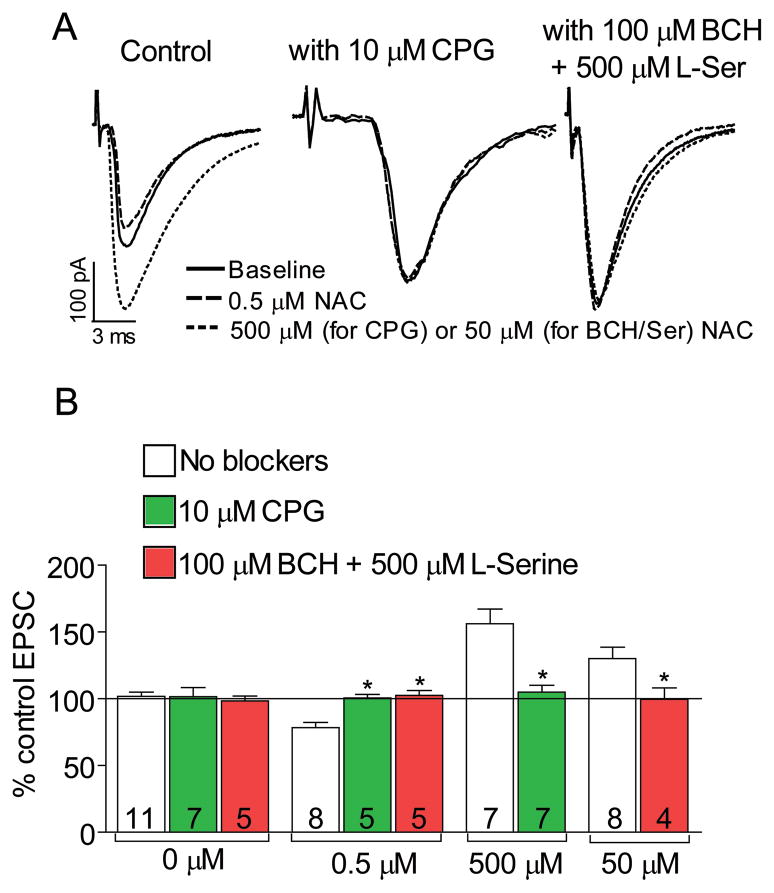

Figure 3.

The effect of NAC on EPSP amplitude was antagonized by blocking system Xc− with 10 μM (S)-4- carboxyphenylglycine (CPG) or by blocking cysteine uptake with a mixture of 100 μM 2-Amino-2- norbornanecarboxylic acid (BCH) + 500 μM L-serine (BCH/Ser). (A) Representative traces for each drug applied to a single cell. (B) CPG or BCH/Ser alone did not affect EPSC amplitude. The inhibitory effect of 0.5 μM NAC was blocked by both drugs (F(2,17)=14.15, p<0.001). The excitatory effects of 500 or 50 μM NAC were blocked by CPG (t(12)=4.20, p=0.001) or BCH/Ser (t(10)=2.21, p=0.051), respectively. For the BCH/Ser experiment 50 μM NAC instead of 500 μM NAC was used (see Results). Data for NAC alone taken from Figure 2A and 2B. * p<0.05, compared to No blockers using a Dunnett’s post hoc test or Student’s t-test.

Since the effect of 500 μM NAC on EPSC amplitude resembled that of 500 μM cysteine, we determined whether the effect of NAC on the EPSC also involved activation of cysteine transporters. We applied 0.5 or 50 μM NAC while blocking Na+-dependent (by 500 μM L-serine) and Na+-independent (by 100 μM 2-amino-2-norbornanecarboxylic acid) cysteine transporters (mixture denoted BCH/Ser) (33). We used 50 μM instead of 500 μM NAC in the BCH/Ser experiment because higher doses of NAC required higher doses of BCH/Ser, which alone reduced EPSC amplitude. The results show that similar to CPG, BCH/Ser blocked both inhibitory and excitatory effects of NAC on the EPSC (Figure 3). These data indicate that activation of system Xc− and uptake via cysteine transporters are necessary for NAC to alter EPSCs in NAcore slices.

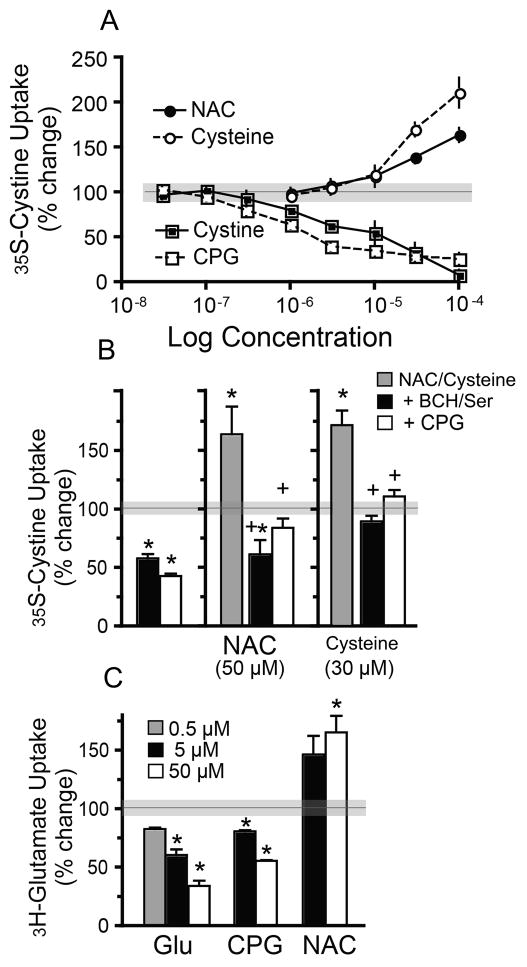

NAC enhances system Xc− activity by acting on cysteine transporters

The involvement of cysteine transporters in the effects of NAC was surprising, and to further examine the role of cysteine transporters in NAC-induced changes, we used primary astrocyte cultures and measured uptake of 35S-cystine(25). The cultures were incubated in 35S-cystine alone and in the presences of increasing concentrations of unlabeled cystine. As expected, with increasing concentrations of cystine (a competitive substrate for system Xc−) the uptake of 35S-cystine declined in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4A). A similar reduction in uptake was seen when adding increasing concentrations of CPG (system Xc− inhibitor). Since NAC is a cystine prodrug it was expected to mimic the effect of cystine on 35S-cystine uptake. However, while 1 or 3 μM NAC did not produce a significant effect, higher concentrations enhanced 35S-cystine uptake. Enhanced 35S-cystine uptake was also seen when cysteine was added to the incubating solution, and akin to EPSC amplitude, the effects of NAC and cysteine were blocked both by CPG and by the cysteine transporter blockers BCH/Ser (Figure 4B). To ensure that 35S-cystine had not been reduced to cysteine and thereby transported by cysteine transporters, we measured the Na+-independent uptake of 3H-glutamate (Figure 4C). Again, while addition of glutamate or CPG reduced 3H-glutamate uptake, NAC produced a concentration-dependent facilitation. The overall results in Figure 4 suggest that NAC does not activate system Xc− by acting as a substrate either directly or by being converted into cystine, but rather acts similar to cysteine by entering the cell through cysteine transporters (34) and facilitating the activation of system Xc− via an undetermined intracellular mechanism.

Figure 4.

N-acetylcysteine and cysteine increased 35S-cystine or 3H-glutamate uptake by system Xc− in cultured astrocytes and this effect was blocked by the Xc− blocker (S)-4-carboxyphenylglycine (CPG; 10 μM), or a mixture of cysteine transporters blockers 2-Amino-2-norbornanecarboxylic acid (BCH) and L- serine (BCH/Ser; 500 μM each). All experiments were performed in the presence of aspartate and acivicin to block system XAG− and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (27) (A) Uptake of 35S-cystine in the presence of increasing concentrations of cystine (■), NAC (●), cysteine (○), and CPG (□) presented as % change from baseline (horizontal line, gray denotes s.e.m.). Cystine (F(8,26)=46.8, p<0.001) and CPG (F(5,17)=36.9, p<0.001) inhibited 35S-cystine uptake, while NAC (F(5,23)=69.8, p<0.001) and cysteine (F(5,17)=57.3, p<0.001) increased 35S-cystine uptake. Gray area around the line at 100 indicates s.e.m. in the absence of drug. (B) CPG or BCH/Ser reversed NAC- and cysteine-induced increase in 35S-cystine uptake (F(8,32)=25.89, p<0.001). (C) Unlabeled glutamate (F(3,11)=83.5, p<0.001) and CPG (F(3,11)=83.5, p<0.001) inhibited whereas NAC (F(2,8)=7.2, p=0.025) enhanced 3H-glutamate uptake. N= 3–4 for each group and each determination is the average of 3 replicate wells. * p<0.05 compared to baseline; +, p<0.05, compared to NAC or cysteine alone.

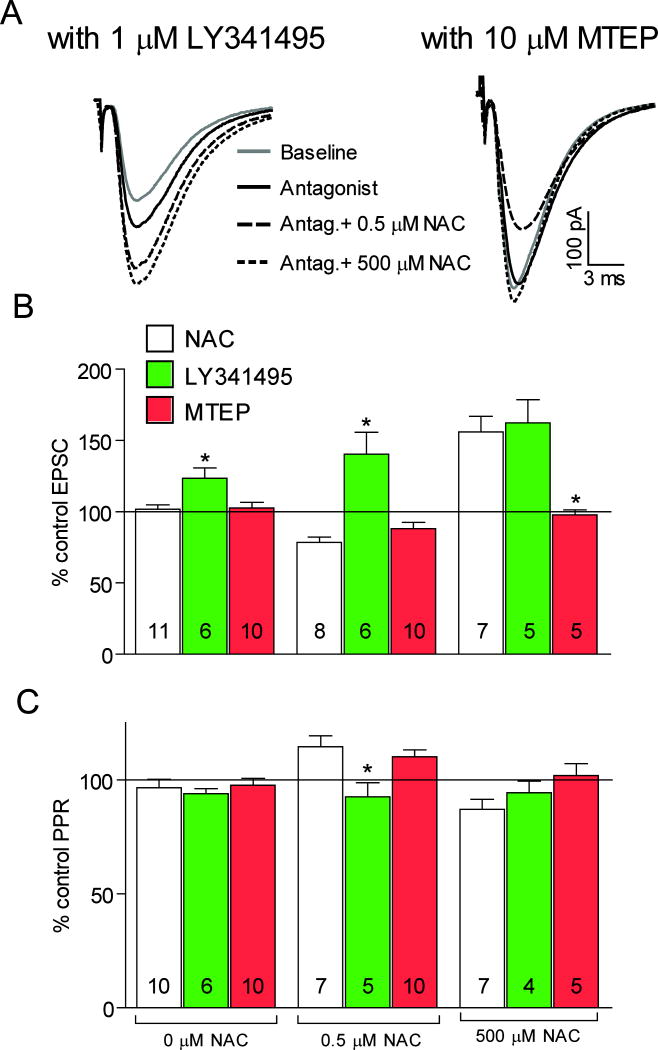

The effects of NAC on EPSCs are differentially mediated by mGluR2/3 and mGluR5

The results so far indicated that NAC altered glutamate transmission in the NAcore by activating system Xc− (4). We next determined whether the effects of NAC on EPSCs were mediated by mGluR activation. mGluR2/3 and mGluR5 are abundant in the nucleus accumbens (35–38), play a role in the induction of LTP and LTD in the NAcore (21), and are implicated in drug addiction (18). In addition, NAC has been shown to block relapse to cocaine through activation of mGluR2/3 (29). Thus, we measured the effect of NAC on EPSCs in the presence of LY341495, a mGluR2/3 antagonist, or MTEP, a mGluR5 negative allosteric modulator (Figure 5). LY314195 alone increased EPSC amplitude, while MTEP had no effect. LY314195 also prevented the reduction in EPSC amplitude produced by 0.5 μM NAC and prevented the NAC-induced change in PPR while MTEP did not. In contrast, the capacity of 500 μM NAC to augment EPSC amplitude, was not blocked by LY341495, but was blocked by MTEP. The PPR ratio was not affected by the addition of either drug compared to 500 μM NAC alone. Together, these results show that while both the inhibitory and excitatory effects of NAC are induced by an elevation in extracellular glutamate concentrations, the inhibitory effect was mediated by presynaptic mGluR2/3 while the excitatory effect was mediated by postsynaptic mGluR5.

Figure 5.

The effects of NAC on neurotransmission are mediated through mGluRs. (A) Representative excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). (B) (2S)-2-Amino-2-[(1S,2S)-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl]-3-(xanth-9-yl) propanoic acid (LY341495) (1 μM) increased EPSC amplitude, while -((2-Methyl-1,3-thiazol-4- yl)ethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MTEP) (5 μM) was without effect (F(2,26)=6.42, p=0.006). LY341495 prevented the reduction in EPSC amplitude induced by 0.5 μM NAC, while MTEP was without effect (F(2,23)=16.13, p<0.001). Conversely, LY341495 was without effect on the increase in EPSC amplitude produced by 500 μM NAC, while MTEP abolished the increase (F(2,16)=8.58, p=0.004). (C) Neither LY341495 nor MTEP alone affected the PPR ratio, while LY341495 but not MTEP prevented the increase in PPR after 0.5 μM NAC (F(2,20)=5.76, p=0.012). The PPR ratio after 500 μM NAC alone was not significantly changed by MTEP or LY341495. * p<0.05 compared to NAC (white bar) using a Dunnett’s post hoc.

NAC and MTEP synergize to inhibit cocaine-seeking

The effect of NAC on EPSCs seems to be determined by the balance between mGluR2/3 and mGluR5 activation. This balance is potentially important for the efficacy of NAC in inhibiting the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. It was previously found that either an antagonist of mGluR2/3 or a positive allosteric modulator of mGluR5 blocks NAC-induced inhibition of cocaine-seeking reinstatement (21,29). Since NAC-induced elevation in nonsynaptic glutamate activates both mGluR2/3 and mGluR5, the stimulation of mGluR5 by higher concentrations of NAC may actually promote cocaine-seeking reinstatement. Therefore, we determined whether combining MTEP with NAC might improve the capacity of NAC to inhibit cocaine-seeking. The same cocaine-training procedure as in Figure 1 was used, but rats were injected with either NAC (10 mg/kg, i.p) or saline 2 hours before cocaine priming (10 mg/kg i.p.) in combination with MTEP (0.1 mg/kg, ip) or saline administered together with NAC and 30 min before cocaine (Figure 6A). At the doses used, neither of NAC or MTEP alone affected cocaine-induced reinstatement of lever pressing compared with the saline control. However, figure 6B shows that the combination of NAC and MTEP significantly reduced lever pressing to extinction levels.

Discussion

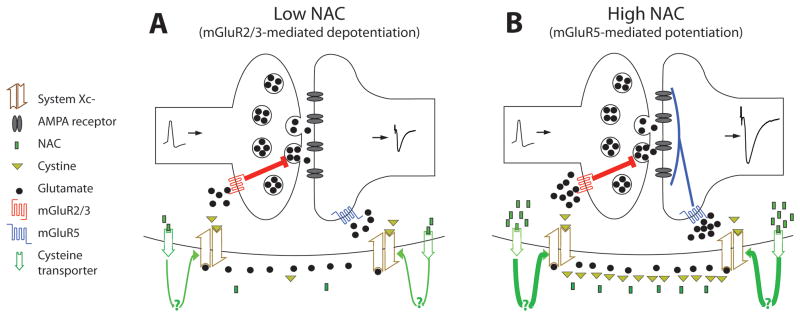

Systemic administration of NAC decreases the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (4,5,7,29,39). This has been proposed to be an outcome of NAC being deacetylated to cysteine and dimerized to cystine, which activates glial system Xc− to exchange extracellular cystine for intracellular glutamate; thereby elevating nonsynaptic glutamate (2). This, in turn, counteracts the reduced extrasynaptic levels of glutamate found after withdrawal from cocaine, and restores extrasynaptic glutamate levels which activate the mGluR2/3; thereby reducing synaptic glutamate release probability and decreasing cocaine-seeking (5,29). Here we show that NAC acts directly in the NAcore to inhibit cocaine-seeking, and demonstrate a requirement for both system Xc− and cysteine transporters in NAC’s ability to indirectly stimulate extrasynaptic mGluRs. While lower concentrations of NAC inhibit glutamate transmission onto NAcore spiny cells via activation of presynaptic mGluR2/3, higher concentrations countermand this effect by stimulating mGluR5 and potentiating EPSC amplitude (see Figure 7 for a schematic illustration). Finally, these opposite effects of mGluR2/3 and mGluR5 on the EPSC were revealed by blocking the capacity of NAC to stimulate mGluR5, and thereby potentiating the ability of NAC to inhibit cocaine-seeking; presumably by unmasking the presynaptic effect of mGluR2/3 stimulation by NAC.

Figure 7.

The effect of NAC on evoked EPSCs in the NAcore. (A) A low dose of NAC (0.5 μM) is taken up by cysteine transporters (presumably following deacetylation in the extracellular space), and via an unknown mechanism stimulates system Xc−. The increase in nonsynaptic extracellular glutamate is sufficient to activate presynaptic inhibitory mGluR2/3, but not to activate postsynaptic mGluR5. This results in presynaptic inhibition of the EPSC amplitude. (B) A high dose of NAC (>5μM) enters the cell via cysteine transport and further accelerates the activity of the Xc−. The higher extracellular glutamate levels activate both mGluR2/3 and mGluR5, but the excitatory effect of mGluR5 countermands the inhibitory effect of mGluR2/3, resulting in increased EPSC amplitude.

NAC actions require cysteine transporters and system Xc−

NAC is deacetylated to cysteine, which is rapidly oxidized to cystine (40) and then transported by system Xc− into the cells, where it is reduced to cysteine for glutathione synthesis (41). Here, we demonstrated that the effects of NAC on mGluR regulation of synaptic strength depends not only on activating system Xc− but also requires cysteine transporters. This is consistent with a previous report showing that NAC elevates intracellular cysteine levels by being deacetylated to cysteine and transported into cells (34). The involvement of cysteine transporters was further confirmed in cultured astroglia where NAC-elevated 35S-cystine or 3H-glutamate uptake through system Xc− required cysteine transporters. A similar effect of NAC on 35S-cystine uptake was reported previously for non-glial cells (32,33). Although these data indicate that NAC must be internalized via cysteine transporters in order to increase system Xc− activity, the intracellular signaling mechanism by which this occurs remains unknown. Interestingly, the dose-dependent bidirectional effect of NAC on excitatory transmission in the NAcore mimicked the actions of both cystine and cysteine. Thus, in the nanomolar range NAC mimicked the effect of cystine by inhibiting EPSCs, and akin to cysteine, NAC increased EPSC amplitude in the 50–500 μM range. It was surprising that high dose cystine continued to reduce EPSC amplitude, and may be indicative of what has been observed where concentrations of cystine above 1 μM did not induce further increases in extracellular glutamate in the NAcore (29).

NAC stimulates both mGluR2/3 and mGluR5

The inhibitory effect of low dose NAC on EPSC amplitude was blocked by a mGluR2/3 antagonist, while the potentiation of EPSC amplitude was blocked by a mGluR5 antagonist. It has been suggested that endogenous levels of glutamate have higher potency at mGluR2/3 than other mGluR subtypes (42,43). This is supported by the fact that mGluR2/3, but not mGluR5, are tonically activated by low endogenous glutamate levels, as indicated by the facts that an mGluR2/3 blocker increases in vivo field EPSCs (5), extracellular glutamate concentrations (44), and in vitro EPSCs (Figure 5). In addition, the inhibitory effect of low dose NAC was accompanied by a change in PPR, implying a presynaptic mechanism, consistent with the presynaptic localization of mGluR2/3 (45,46) versus the postsynaptic location of mGluR5 (35,45,46). Finally, the inhibitory effect of 0.5 μM NAC on the EPSC and PPR was blocked by an mGluR2/3-selective dose of LY341495 (47,48), but not by MTEP.

Compared with the mGluR2/3-dependent effect of nM NAC, the increase in EPSC amplitude following higher concentrations of NAC (>5 μM) was mGluR5-dependent. This is consistent with previous studies showing positive modulation of EPSCs by mGluR5 (45,49). Presumably, the synaptic potentiation by higher doses arises from further NAC-induced increases in the activity of system Xc−, and the corresponding increases in extracellular glutamate that would activate the relatively lower-affinity mGluR5. Consistent with anatomical localization studies (35,45,46), the lack of change in PPR after high dose NAC supports a postsynaptic mechanism. In addition, mGluR5 are expressed by glia and regulate calcium-dependent release of glutamate from glia, which could further contribute to the stimulation of neuronal mGluRs (50). Although the doses of NAC required in vitro to indirectly stimulate mGluR5 were micromolar, this may reflect in part reduced basal extracellular glutamate imposed by constant perfusion of tissue slices (29). Importantly, since the effect of even the relatively low dose of 10 mg/kg NAC could be improved by blocking mGluR5, in vivo the stimulation of mGluR5 by NAC appears to contribute to the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Although we focused on mGluR2/3 and mGluR5, NAC-induced elevation of glutamate may also activate mGluR1 and group III mGluRs, both of which are expressed in the rat nucleus accumbens (51–53). Activation of presynaptic group III mGluRs negatively regulates EPSC amplitude (54,55), while mGluR1 stimulation increases the presynaptic release of glutamate (56,57), either of which could contribute to our measurements of EPSC amplitude and PPR.

Balancing the stimulation of mGluR2/3 and mGluR5 in NAC treatment of cocaine relapse

Elevating nonsynaptic glutamate levels by NAC activation of system Xc− is thought to re-establish tone on mGluR2/3 in the NAcore of cocaine-withdrawn animals, thereby inhibiting synaptic glutamate transmission and preventing the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (4,5,7,39). Our results support this conclusion by showing that NAC microinfusion directly into the NAcore inhibited cocaine-seeking in a mGluR2/3-dependent manner. However, the present study also complicates this view of NAC action by showing that, at least at higher concentrations, NAC can stimulate mGluR5 also via activating system Xc− release of glutamate. Importantly, activating mGluR5 reduces the efficacy of NAC (21), and antagonizing mGluR5 blocks cocaine-seeking (19,20,58–60). Thus, NAC activation of mGluR5 should countermand the capacity of NAC-induced mGluR2/3 activation to inhibit the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Our finding that blocking mGluR5 augments the capacity of NAC to inhibit cocaine-seeking supports a mGluR-dependent bidirectional effect of NAC on cocaine-seeking. Recently, NAC has been used with only partial success in clinical trials to reduce cocaine or tobacco craving and relapse (9,10,61–63). Taken together, the data in this report indicate that combining NAC with an mGluR5 antagonist might improve the efficacy of NAC in treating addiction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Charles Thomas and Ms. Megan Hensley for their assistance in animal training and Dr. Art Riegel for his advice in conducting the electrophysiological experiments. This research was supported by USPHA grants DA015369, DA012513, and DA003906.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chen BT, Hopf FW, Bonci A. Synaptic plasticity in the mesolimbic system: therapeutic implications for substance abuse. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalivas PW. The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:561–572. doi: 10.1038/nrn2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. New medications for drug addiction hiding in glutamatergic neuroplasticity. Mol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Tang XC, Toda S, et al. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:743–749. doi: 10.1038/nn1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moussawi K, Zhou W, Shen H, Reichel CM, See RE, Carr DB, et al. Reversing cocaine-induced synaptic potentiation provides enduring protection from relapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:385–390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011265108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBean GJ. Cerebral cystine uptake: a tale of two transporters. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madayag A, Lobner D, Kau KS, Mantsch JR, Abdulhameed O, Hearing M, et al. Repeated N-acetylcysteine administration alters plasticity-dependent effects of cocaine. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13968–13976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2808-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knackstedt LA, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW. Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaRowe SD, Myrick H, Hedden S, Mardikian P, Saladin M, McRae A, et al. Is cocaine desire reduced by N-acetylcysteine? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1115–1117. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knackstedt LA, LaRowe S, Mardikian P, Malcolm R, Upadhyaya H, Hedden S, et al. The role of cystine-glutamate exchange in nicotine dependence in rats and humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:841–845. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray JE, Everitt BJ, Belin D. N-Acetylcysteine reduces early- and late-stage cocaine seeking without affecting cocaine taking in rats. Addict Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou W, Kalivas PW. N-acetylcysteine reduces extinction responding and induces enduring reductions in cue- and heroin-induced drug-seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:338–340. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalivas PW, Volkow N, Seamans J. Unmanageable motivation in addiction: a pathology in prefrontal-accumbens glutamate transmission. Neuron. 2005;45:647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baptista MA, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Preferential effects of the metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 on conditioned reinstatement versus primary reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a potent conventional reinforcer. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4723–4727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossert JM, Gray SM, Lu L, Shaham Y. Activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell attenuates context-induced relapse to heroin seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2197–2209. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters J, Kalivas PW. The group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, LY379268, inhibits both cocaine- and food-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:143–149. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gass JT, Osborne MP, Watson NL, Brown JL, Olive MF. mGluR5 antagonism attenuates methamphetamine reinforcement and prevents reinstatement of methamphetamine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:820–833. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenny PJ, Markou A. The ups and downs of addiction: role of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenny PJ, Paterson NE, Boutrel B, Semenova S, Harrison AA, Gasparini F, et al. Metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor antagonist MPEP decreased nicotine and cocaine self-administration but not nicotine and cocaine-induced facilitation of brain reward function in rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:415–418. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin-Fardon R, Baptista MA, Dayas CV, Weiss F. Dissociation of the effects of MTEP [3-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]piperidine] on conditioned reinstatement and reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a conventional reinforcer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:1084–1090. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.151357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moussawi K, Pacchioni A, Moran M, Olive MF, Gass JT, Lavin A, et al. N-Acetylcysteine reverses cocaine-induced metaplasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:182–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 6. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorelova N, Yang CR. The course of neural projection from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens in the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;76:689–706. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM. Puttinga spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ducis I, Norenberg LO, Norenberg MD. The benzodiazepine receptor in cultured astrocytes from genetically epilepsy-prone rats. Brain Res. 1990;531:318–321. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90793-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bender AS, Reichelt W, Norenberg MD. Characterization of cystine uptake in cultured astrocytes. Neurochem Int. 2000;37:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotgreave IA, Schuppe-Koistinen I. A role for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in the transport of cystine into human endothelial cells: relationship to intracellular glutathione. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1222:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melendez RI, Vuthiganon J, Kalivas PW. Regulation of extracellular glutamate in the prefrontal cortex: focus on the cystine glutamate exchanger and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:139–147. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran MM, McFarland K, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW, Seamans JK. Cystine/glutamate exchange regulates metabotropic glutamate receptor presynaptic inhibition of excitatory transmission and vulnerability to cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6389–6393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1007-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parnas H, Segel LA. Ways to discern the presynaptic effect of drugs on neurotransmitter release. J Theor Biol. 1982;94:923–941. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zucker RS. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:13–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Issels RD, Nagele A, Eckert KG, Wilmanns W. Promotion of cystine uptake and its utilization for glutathione biosynthesis induced by cysteamine and N-acetylcysteine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:881–888. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knickelbein RG, Seres T, Lam G, Johnston RB, Jr, Warshaw JB. Characterization of multiple cysteine and cystine transporters in rat alveolar type II cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L1147–1155. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.6.L1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arakawa M, Ito Y. N-acetylcysteine and neurodegenerative diseases: Basic and clinical pharmacology. Cerebellum. 2007:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14734220601142878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitrano DA, Smith Y. Comparative analysis of the subcellular and subsynaptic localization of mGluR1a and mGluR5 metabotropic glutamate receptors in the shell and core of the nucleus accumbens in rat and monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:788–806. doi: 10.1002/cne.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohishi H, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Distribution of the mRNA for a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR3) in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:252–266. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohishi H, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Distribution of the messenger RNA for a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR2, in the central nervous system of the rat. Neuroscience. 1993;53:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shigemoto R, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Sugihara H, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR5, in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163:53–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90227-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kau KS, Madayag A, Mantsch JR, Grier MD, Abdulhameed O, Baker DA. Blunted cystine-glutamate antiporter function in the nucleus accumbens promotes cocaine-induced drug seeking. Neuroscience. 2008;155:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bannai S, Sato H, Ishii T, Sugita Y. Induction of cystine transport activity in human fibroblasts by oxygen. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18480–18484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dringen R. Metabolism and functions of glutathione in brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62:649–671. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cartmell J, Schoepp DD. Regulation of neurotransmitter release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2000;75:889–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130:1007S–1015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xi ZX, Baker DA, Shen H, Carson DS, Kalivas PW. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:162–171. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinheiro PS, Mulle C. Presynaptic glutamate receptors: physiological functions and mechanisms of action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:423–436. doi: 10.1038/nrn2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marek GJ, Wright RA, Schoepp DD, Monn JA, Aghajanian GK. Physiological antagonism between 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) and group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in prefrontal cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Kitai ST, Xiang Z. Modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission by endogenous glutamate acting on presynaptic group II mGluRs in rat substantia nigra compacta. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:778–787. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hermans E, Challiss RA. Structural, signalling and regulatory properties of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptors: prototypic family C G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem J. 2001;359:465–484. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.D’Ascenzo M, Fellin T, Terunuma M, Revilla-Sanchez R, Meaney DF, Auberson YP, et al. mGluR5 stimulates gliotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1995–2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corti C, Aldegheri L, Somogyi P, Ferraguti F. Distribution and synaptic localisation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4) in the rodent CNS. Neuroscience. 2002;110:403–420. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang CC, Yeh CM, Wu MY, Chang AY, Chan JY, Chan SH, et al. Cocaine withdrawal impairs metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4194–4203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5239-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohishi H, Akazawa C, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Distributions of the mRNAs for L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate-sensitive metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGluR4 and mGluR7, in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1995;360:555–570. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cochilla AJ, Alford S. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated control of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manzoni O, Michel JM, Bockaert J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:1514–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swanson CJ, Baker DA, Carson D, Worley PF, Kalivas PW. Repeated cocaine administration attenuates group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated glutamate release and behavioral activation: a potential role for Homer. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9043–9052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-09043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xi ZX, Shen H, Baker DA, Kalivas PW. Inhibition of non-vesicular glutamate release by group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1204–1212. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumaresan V, Yuan M, Yee J, Famous KR, Anderson SM, Schmidt HD, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) antagonists attenuate cocaine priming- and cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Behav Brain Res. 2009;202:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiamulera C, Epping-Jordan MP, Zocchi A, Marcon C, Cottiny C, Tacconi S, et al. Reinforcing and locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine are absent in mGluR5 null mutant mice. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:873–874. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee B, Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Adewale AS, Spealman RD. Attenuation of behavioral effects of cocaine by the Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5 Antagonist 2-Methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine in squirrel monkeys: comparison with dizocilpine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:1232–1240. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dean O, Giorlando F, Berk M. N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry: current therapeutic evidence and potential mechanisms of action. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011;36:78–86. doi: 10.1503/jpn.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.LaRowe SD, Mardikian P, Malcolm R, Myrick H, Kalivas P, McFarland K, et al. Safety and tolerability of N-acetylcysteine in cocaine-dependent individuals. Am J Addict. 2006;15:105–110. doi: 10.1080/10550490500419169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mardikian PN, LaRowe SD, Hedden S, Kalivas PW, Malcolm RJ. An open-label trial of N-acetylcysteine for the treatment of cocaine dependence: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]