Abstract

Lapatinib, an oral, small-molecule, reversible inhibitor of both EGFR and HER2, is highly active in HER2 positive breast cancer as a single agent and in combination with other therapeutics. However, resistance against lapatinib is an unresolved problem in clinical oncology. Recently, interest in the use of natural compounds to prevent or treat cancers has gained increasing interest because of presumed low toxicity. Quercetin-3-methyl ether, a naturally occurring compound present in various plants, has potent anticancer activity. Here, we found that quercetin-3-methyl ether caused in a significant growth inhibition of lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant breast cancer cells. Western blot data showed that quercetin-3-methyl ether had no effect on Akt or ERKs signaling in resistant cells. However, quercetin-3-methyl ether caused a pronounced G2/M block mainly through the Chk1-Cdc25c-cyclin B1/Cdk1 pathway in lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant cells. In contrast, lapatinib produced an accumulation of cells in the G1 phase mediated through cyclin D1, but only in lapatinib-sensitive cells. Moreover, quercetin-3-methyl ether induced significant apoptosis, accompanied with increased levels of cleaved caspase 3, caspase 7 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in both cell lines. Overall, these results suggested that quercetin-3-methyl ether might be a novel and promising therapeutic agent in lapatinib-sensitive or -resistant breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Breast cancer, HER2, lapatinib, natural product, quercetin-3-methyl ether, apoptosis

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death [1] and clearly a significant health problem in terms of both morbidity and mortality. Approximately 20–30% of breast cancer tumors show overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) protein [2]. Deregulation of the HER-mediated signaling network through the amplification of the HER2 gene has been implicated in the pathogenesis of breast cancer, [2,3]. HER2 overexpression is directly linked to deregulated activation of intracellular mitogenic signaling, resulting in aggressive tumor behavior and resistance to chemotherapy [4]. An increase in HER2 expression also enhances the malignant phenotype of cancer cells, including those with metastatic potential [3,4]. Indeed, HER2 positive (HER2+) breast cancer is known to portend a poor clinical outcome, increase resistance to some chemotherapeutic drugs, and appears to be more prevalent in younger women [2–4].

Lapatinib is an oral, small-molecule, reversible inhibitor of both the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and HER2 [2,4,5] and directly targets the tyrosine-kinase domain of these receptors. This small molecule reversibly binds to the cytoplasmic ATP-binding site of the kinase domain and blocks receptor phosphorylation and activation [6]. The interaction prevents the phosphorylation and subsequent signal transduction of the Ras/Raf mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/Akt pathways, resulting in decreased growth, metastasis and angiogenesis, increased sensitivity to apoptotic signals, and genetic instability [4–6]. Available evidence suggests that HER2 might be more important in breast cancer development/progression than the EGFR [7]. Sensitivity to lapatinib is directly related to expression of HER2 but not the EGFR [6,7]. Preclinical and clinical studies indicate that lapatinib is highly active in HER2+ breast cancer as a single agent and in combination with other therapeutics [5,6,8]. In March 2007, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved lapatinib for use in combination with capecitabine in the treatment of locally advanced breast cancer or metastatic breast cancer progressing after treatment with regimens containing anthracycline, taxane, and trastuzumab [2,6,9]. Moreover, lapatinib is under investigation in combination with anthracycline and taxanes in neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings [6]. Another potential field of investigation for this drug is related to its ability to restore hormonal sensitivity of HER2, hormone receptor positive breast cancer cells [6]. However, its efficacy is limited by either primary or acquired resistance. In addition, the most frequently reported adverse events of this drug are diarrhea, rash, nausea, vomiting, fatigue and headache [5,6]. Hence, the development of novel agents for breast cancer patients, and especially lapatinib-resistant patients, is important. In recent years, because of presumed low toxicity, interest in the use of natural compounds to prevent or treat cancers has been growing. Flavonoids are phenylbenzo-γ-pyrone derivatives and comprise a very large class of biologically active compounds ubiquitous in plants, many of which have been used in traditional Eastern medicine for thousands of years [10,11]. Quercetin-3-methyl ether is a flavonoid found in various plants, including Allagopappus viscosissimus [10], Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten [12], Lychnophora staavioides [13], and Rhamnus species [14]. Research data have shown that querectin-3-methyl ether is a potential anti-carcinogenic agent against several human tumor cell lines, including HL-60, A431, SK-OV-3, HeLa, and HOS [11]. The HL-60 cell line is reportedly the most sensitive to the anti-proliferative effect of quercetin-3-methyl ether (IC50 = 14.3 ± 4.6 µM) [11]. Whether quercetin-3-methyl ether has an effect on breast cancer cell growth has not yet been explored. Here, we report that quercetin-3-methyl ether strongly suppresses anchorage-dependent or -independent growth of human breast cancer cells that are sensitive (SK-Br-3) or resistant (Sk-Br-3-Lap R) to lapatinib treatment.

Methods and Materials

Chemicals

Quercetin-3-methyl ether was obtained from Analyticon Discovery (Potsdam, Germany). McCoy’s 5A medium (McCoy), basal medium Eagle (BME), gentamicin, and L-glutamine were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gemini Bio-Products (Calabasa, CA). The antibodies against phosphorylated Akt (Ser473), total Akt, phosphorylated ERKs (Tyr202/Tyr204), total ERKs, phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinases (Thr183/Tyr185), total c-Jun N-terminal kinases, phosphorylated p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), total p38, phosphorylated cyclin B1 (Ser147), total cyclin B1, phosphorylated Cdk1 (Tyr15), total Cdk1, phosphorylated Cdc25c (Ser216), total Cdc25c, phosphorylated Chk1 (Ser345), total Chk1, cyclin D1, cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175), cleaved caspase 7 (Asp198) and cleaved PARP (Asp214) were purchased from Cell Signaling Biotechnology (Beverly, MA). The protein assay kit was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The CellTiter96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay Kit was from Promega (Madison, WI).

Cell culture

Lapatinib-resistant SK-Br-3 (SK-Br-3-Lap R) cells were isolated in the Laboratory of Cell Biology and Biotherapy at the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Naples, Italy (Refer to abstract presented at ASCO 2011). Parental SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cells were cultured in monolayers at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in 10% FBS/McCoy supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml; Invitrogen). SK-Br-3 Lap R cells were routinely maintained in 1 µM lapatinib.

Anchorage-dependent growth assay

Cells were seeded (5×103 cells/well) in 96-well plates with 10% FBS/McCoy and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator overnight. Cells were then fed with fresh medium and treated with lapatinib (0.1 µM) or quercetin-3-methyl ether (0–10 µM). After culturing for various times, 20 µl of Cell Titer 96 Aqueous One Solution were added to each well, and the cells were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Absorbance was measured at 490 and 690 nm.

Western blotting

After cells (1×106) were cultured in a 10-cm dish overnight, they were starved in serum-free medium for another 24 h to eliminate the influence of FBS on the activation of MAPKs. The cells were then treated with lapatinib (0.1 µM) or quercetin-3-methyl ether (0–10 µM) for 16 or 48 h in culture medium containing 10% FBS. The harvested cells were disrupted, and the supernatant fractions were boiled for 5 min. The protein concentration was determined using a dye-binding protein assay kit (Bio-Rad) as described in the manufacturer’s instruction manual. Lysate protein (50 µg) was subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Bioscience). After blotting, the membranes were incubated with the respective specific primary antibody at 4°C overnight. Protein bands were visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Biosciences) after hybridization with an AP-linked secondary antibody. Band density was quantified using the ImageJ software program (NIH).

Anchorage-independent growth assay

Cells (8×103/ml) were exposed to lapatinib (0.1 µM) or quercetin-3-methyl ether (0–10 µM) in 1 ml of 0.33% BME agar containing 10% FBS or in 3 ml of 0.5% BME agar containing 10% FBS. The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 14 or 21 days, after which time the cell colonies were counted under a microscope with the aid of the Image-Pro Plus software program (v.4, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) [15].

Cell cycle assay

Cells were seeded (4×105 cells/well) in 60-mm dishes with 10% FBS/McCoy and incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were then starved in serum-free medium for 24 h followed by treatment for 16 or 48 h with lapatinib (0.1 µM) or quercetin-3-methyl ether (0–10 µM) in 10% FBS/McCoy. The cells were trypsinized, then washed twice with cold PBS, and finally fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol at −20°C overnight. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, incubated with 20 mg/ml RNase A and 200 mg/ml propidium iodide in PBS at room temperature for 30 min in the dark, and subjected to flow cytometry using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Data were analyzed using ModFit LT (Verity Software House, Inc., Topsham, ME).

Apoptosis assay

Annexin V and propidium iodide staining were used to visualize apoptotic cells in a similar procedure as described above but without pre-fixing with 70% ethanol. Cells were stained using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (MBL International Corporation, Watertown, MA) and propidium iodide according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were analyzed by two-color flow cytometry. The emission fluorescence of the Annexin V conjugate was detected and recorded through a 530/30 bandpass filter in the FL1 detector. Propidium iodide was detected in the FL2 detector through a 585/42 bandpass filter. Apoptotic cells were only those that stained positive for Annexin V and negative for propidium iodide, located in the bottom right quadrant.

Statistical analysis

As necessary, data are expressed as means ± S.E. and significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA. A probability value of p < 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS, Inc.).

Results

Quercetin-3-methyl ether strongly inhibits anchorage-dependent or- independent growth of lapatini-sensitive and -resistant cells

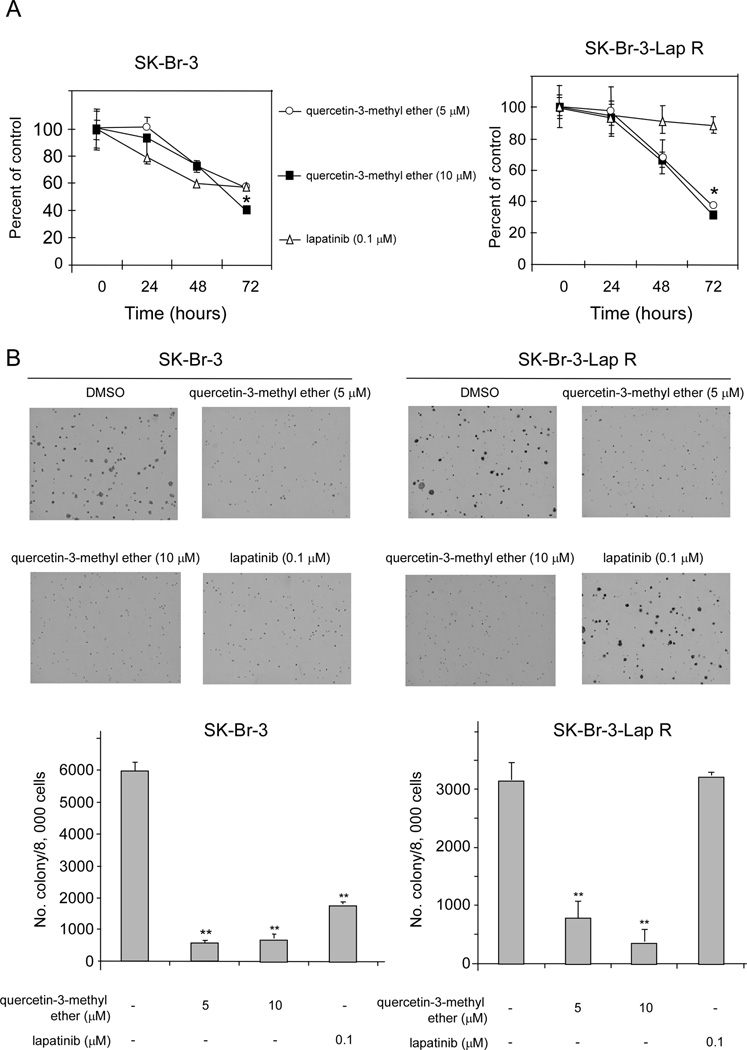

We have previously demonstrated that SK-Br-3-Lap R cells have an IC50 to lapatinib that is significantly higher than that observed with parental SK-Br-3 cells (4 µM vs. 140 nM), and that following treatment with lapatinib, Lap-R cells show persistent activation of MAPK and Akt that is completely suppressed by treatment with the drug in the parental cells [16]. To determine the effect of quercetin-3-methyl ether on growth of each of the two cell lines, we performed both anchorage-dependent and -independent growth assays. The anchorage-dependent assay data showed that quercetin-3-methyl ether treatment resulted in a significant dose- and time-dependent inhibition of growth in both cell lines. The low dose (5 µM) of quercetin-3-methyl ether reduced growth of SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R by 44 and 63%, respectively (Figure 1A). A higher dose (10 µM) decreased growth of SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R by 60 and 69%, respectively (Figure 1A). In contrast, lapatinib suppressed growth of SK-Br-3 cells, but had no effect on SK-Br-3-Lap R cell growth (Figure 1A). Additional results indicated that quercetin-3-methyl ether strongly inhibited colony formation in both cell types (Figure 1B). The lower dose (5 µM) of quercetin-3-methyl ether caused a 90 and 75% decrease in colony formation by sensitive and resistant cells, respectively (Figure 1B) and the higher dose (10 µM) reduced colony formation by 88 and 89%, respectively (Figure 1B). Lapatinib decreased colony number by 70% in the sensitive cells, but had no effect on the resistant cells (Figure 1B). These data indicated that quercetin-3-methyl ether significantly suppressed growth in both the SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cell types.

Figure 1.

Quercetin-3-methyl ether strongly suppresses anchorage-dependent or independent growth of SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cells. (A) Quercetin-3-methyl ether inhibits anchorage-dependent cell growth in lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant breast cancer cells. Cells were treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (0, 5, or 10 µM) or lapatinib (0.1 µM) in 10% FBS/McCoy for various times. At the end of each treatment time, cell growth was measured by MTS assay. Data are shown as means ± S.E. The asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) between groups treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether and the group treated with DMSO. (B) Quercetin-3-methyl inhibits anchorage-independent cell growth in lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant cells. Cells were treated as described under “Materials and methods” and colonies were counted under a microscope with the aid of Image-Pro Plus software (v.4). Data are shown as means ± S.E. The asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference (p < 0.001) between groups treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether or lapatinib and the group treated with DMSO.

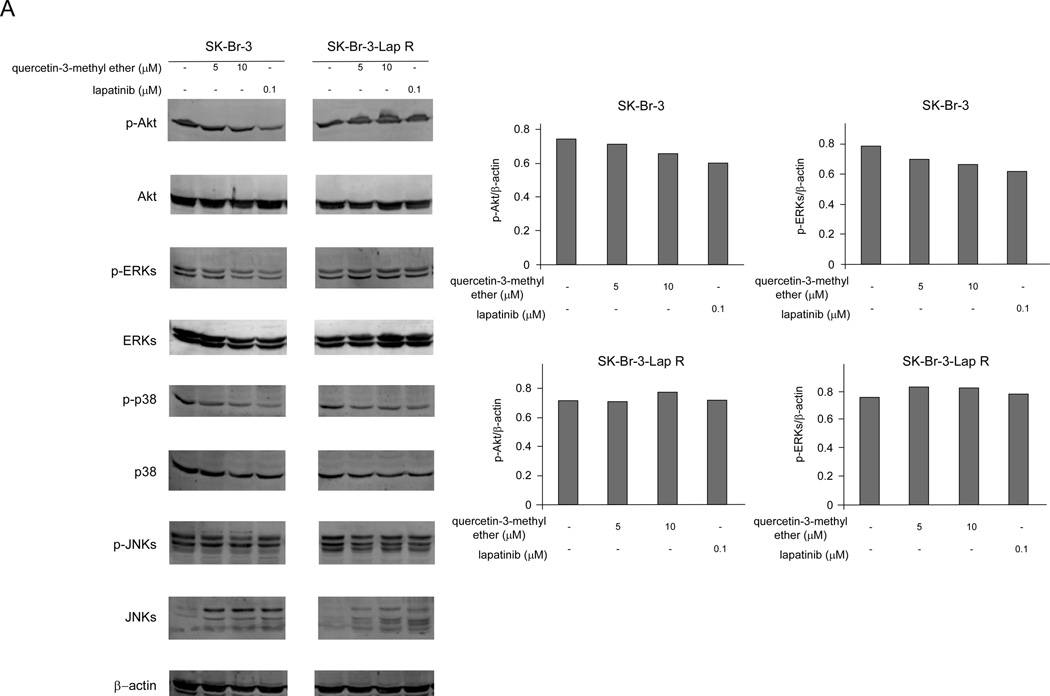

Quercetin-3-methyl ether has no effect on Akt or ERKs signaling in lapatinib-resistant SK-Br-3 cells

We hypothesized that quercetin-3-methyl ether might suppress phosphorylation of Akt and ERKs. Results showed that in the sensitive cells, quercetin-3-methyl ether slightly reduced the phosphorylation of Akt, and ERKs, but had no effect on these kinases in the resistant cells (Figure 2). Lapatinib had a moderately stronger inhibitory effect on phosphorylation of Akt and ERKs in the SK-Br-3 cells, but also had no effect on these proteins in the resistant cells (Figure 2). These data suggested that the mechanism of quercetin-3-methyl ether’s inhibition of breast cancer cell growth might be different from lapatinib.

Figure 2.

Quercetin-3-methyl ether has no significant effect on Akt or MAPKs signaling in lapatinib-resistant SK-Br-3 cells. Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (0, 5 or 10 µM) or lapatinib (0.1 µM) in 10% FBS/McCoy for 16 h. The levels of phosphorylated and total Akt, ERKs, JNKs and p38 proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using the Image J software program.

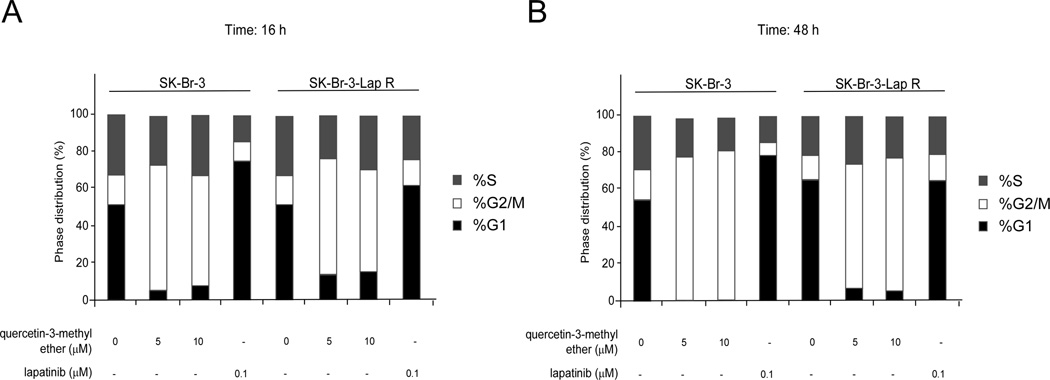

Quercetin-3-methyl ether induces G2/M arrest in the both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant breast cancer cell lines

To determine whether the inhibitory effect of quercetin-3-methyl ether on growth was caused by modulation of cell cycle phase, we analyzed the cell cycle distribution in SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cells following treatment for 16 or 48 h with quercetin-3-methyl ether or lapatinib at various concentrations. Quercetin-3-methyl ether treatment for 16 h resulted in a significant accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase and a reduction in the G1 phase in both cell lines (Figure 3). Lapatinib produced an accumulation of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle only in sensitive cells (Figure 3). Although these differences were evident after 16 h, they became more substantial at 48 h after treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quercetin-3-methyl ether induces significant G2/M arrest in SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cells, whereas lapatinib induces G1 arrest only in sensitive SK-BR-3 cells. Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (0, 5, or 10 µM) or lapatinib (0.1 µM) for 16 or 48 h. Cell cycle analysis was performed using flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean percentages.

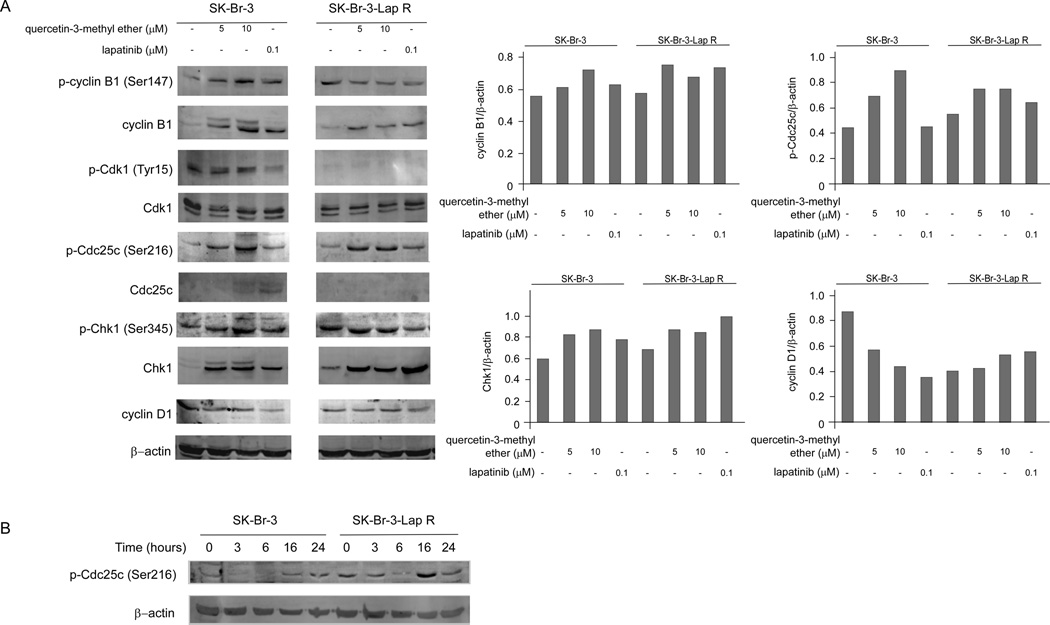

Quercetin-3-methyl ether activates the Chk1/p-Cdc25c (Ser216)/cyclin B1 signaling pathway

The regulation of cell cycle is primarily controlled by a family of cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) complexes [17,18]. At an appropriate time in the cell cycle, the cyclin/Cdk complex is dephosphorylated and activated by Cdc25 [19]. Cdc25c action on the cyclin B/Cdk1 complex is responsible for G2/M progression [17,19]. The checkpoint regulatory proteins Chk1 and Chk2 function by phosphorylating and inhibiting Cdc25c [19]. To determine a possible mechanism to explain the inhibitory effect of quercetin-3-methyl ether, we examined the level of several G2/M arrest-related proteins in the both cell types. Quercetin-3-metyl ether activated Chk1, cyclin B1 and induced phosphorylation of Cdc25c (Ser216) in both cell types (SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R; Figure 4A). The most important finding was that the phosphorylation of Cdc25c was increased substantially by quercetin-3-methyl ether treatment at 16 h, but was less affected by lapatinib (Figure 4A). The level of phosphorylated Cdc25c (Ser216) decreased after 3–6 h of quercetin-3-methyl ether treatment and then increased after 16–24 h of treatment (Figure 4B). These findings indicated that quercetin-3-methyl ether modulates the Chk1/Cdc25c/cyclin B1/Cdk1 pathway to induce G2/M arrest. Although lapatinib also had a small effect on activation of Chk1, cyclin B1 and induction of phosphorylation of Cdc25c (Ser216) in both cell types (SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R; Figure 4A), this drug mainly induced G1 arrest by inhibiting cyclin D1 in lapatinib-sensitive cells (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Quercetin-3-methyl ether activates the Chk1/p-Cdc25c (Ser216)/cyclin B1 signaling pathway in SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cells. (A) Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (0, 5, or 10 µM) or lapatinib (0.1 µM) in 10% FBS/McCoy for 16 h. The levels of phosphorylated and total cyclin B1, Cdk1, Cdc25c and Chk1 proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using the Image J software program. (B) Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (10 µM) in 10% FBS/McCoy for 0–24 h. The level of phosphorylated Cdc25c (Ser216) was determined by Western blot analysis.

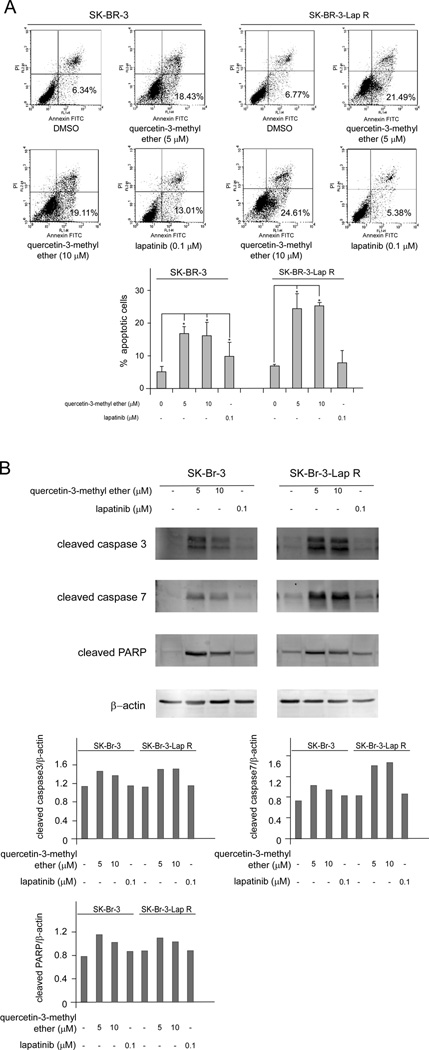

Quercetin-3-methyl ether induces apoptosis accompanied with increases in cleaved caspase 3, caspase 7 and PARP in the both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant cell lines

In order to determine whether quercetin-3-methyl ether decreased growth by inducing cell death, we analyzed apoptosis in SK-Br-3 and SK-Br-3-Lap R cells treated with querctin-3-methyl ether. After quercetin-3-methyl ether or lapatinib treatment for 16 h, no differences in numbers of apoptotic cells were observed in either cell line (data not shown). Lapatinib treatment for 48 h also had no obvious effect on resistant cells (Figure 5A). However, treatment with quercetin-3-methyl ether for 48 h resulted in significant apoptosis in both cell types (Figure 5A). Next, we examined whether quercetin-3-methyl ether induced caspase or poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage (PARP), both of which are hallmarks of apoptosis. Results indicated that the levels of cleaved caspase 3, caspase 7 and PARP were increased in both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant cells after quercetin-3-methyl ether treatment for 48 h (Figure 5B). In contrast, treatment of cells for 48 h with lapatinib had no effect on resistant cells (Figure 5B). Taken together, these results indicated that quercetin-3-methyl ether is a potent inducer of apoptosis in either lapatinib-sensitive or -resistant human breast cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Quercetin-3-methyl ether induces apoptosis accompanied with an increase in cleaved caspase 3, caspase 7 and PARP in both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant breast cancer cell lines. (A) Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (0, 5, or 10 µM) or lapatinib (0.1 µM) for 48 h. Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are shown as means ± S.E. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between groups treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether or lapatinib and the group treated with DMSO. (B) Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 24 h and then treated with quercetin-3-methyl ether (0, 5, or 10 µM) or lapatinib (0.1 µM), in 10% FBS/McCoy for 48 h. The levels of cleaved caspase 3, caspase 7 and PARP were determined by Western blot analysis. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using the Image J software program.

Discussion

Acquired resistance against treatment with HER2 inhibitors is an unresolved problem in clinical oncology. Trastuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the extracellular domain of HER2 [2,4,5]. In spite of its robust clinical activity, about 70% of women on trastuzumab therapy with metastatic HER2-overexpressing breast cancer eventually progress [20]. Some of the trastuzumab-resistant patients (20–30%) might still respond to lapatinib [9]. However, responses are usually short-lived and most patients relapse after a variable latency period [20]. Therefore, research has focused on mechanisms of drug resistance and development of novel agents to overcome resistance. Possible mechanisms of resistance include PI3-KCA/PTEN mutation and enhanced Akt and MAPKs signaling [8,20,21]. SK-Br-3 cells, a HER2+ breast cancer cell line, are naturally devoid of mutations in PI3-KCA, PTEN, BRAF and RAS [8]. Interestingly, lapatinib-resistant SK-Br-3 cells show persistent activation of MAPK and AKT pathways, which are both involved in the intrinsic and acquired resistance of breast cancer cells to anti-HER2 drugs [16,21].

Prevention and therapeutic intervention by phytochemicals is a newer dimension in cancer management. Administration of phytochemicals was shown to prevent initiation, promotion and progression events associated with carcinogenesis in different animal models, and has been suggested to effectively reduce cancer mortality and morbidity [22]. Our study addressed the question of whether quercetin-3-methyl ether might be a potential agent for treatment of breast cancer, and especially lapatinib-resistant breast cancer. This compound significantly suppressed growth and colony formation of both lapatinib-sensitive and lapatinib-resistant cells. When cells were treated with the same concentration (1 µM) of each drug, lapatinib was more effective in inhibiting cell growth in lapatinib-resistant cells (Supplemental Fig. 1). However, lapatinib was much more toxic than quercetin-3-methyl ether and is associated with several side effects. Recent data suggest that a PI3-K or MEK inhibitor can overcome resistance to lapatinib in cancer cells [8,20]. Hence, we hypothesized that quercetin-3-methyl ether might overcome resistance to lapatinib by inhibiting Akt or ERKs. However, our findings showed that following treatment with quercetin-3-methyl ether, the levels of phosphorylated Akt and ERKs were unchanged in resistant cells (Figure 2). This indicated that the mechanism of quercetin-3-methyl ether inhibition of cancer cell growth is different from lapatinib.

Deregulation of cell cycle progression is a universal characteristic of cancer cell growth, and the majority of human cancers have abnormalities in some component of the pathway [23]. Inhibition of unchecked cell cycle regulation in cancer cells could be a potential strategy for the management of cancer. In the present study, quercetin-3-methyl ether caused a pronounced G2/M arrest in both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant cells, whereas lapatinib resulted in a significant G1 block only in lapatinib-sensitive cells. Both compounds inhibit cell growth by inducing cell cycle arrest, but the mechanisms vary. G2/M arrest has been shown to be a protective mechanism that ensures orderly and timely repair of DNA damage and prevents inappropriate mitotic entry [24]. The G2/M checkpoint is the most prominent target of many anticancer agents in tumor cells when these cells have sustained DNA damage induced by therapeutic agents [24]. One of the network complexes that regulates the G2 to M transition has now been revealed to be a Cdc25c-cyclin B1/Cdk1-controlled switch-like system [24]. Initiation of G2 arrest through phosphorylation of Cdc25c on the Ser216 residue, a primary regulator, is critical for G2 checkpoint regulation [25,26]. The DNA damage checkpoint pathway is activated through the Chk1/p-Cdc25C (Ser216) pathway [25,26]. The finding that cyclin B1, phosphorylated Cdc25c (Ser216) and Chk1 levels increased after quercetin-3-methyl ether treatment suggests that this compound causes G2/M blockade mainly through the Chk1/Cdc25c/cyclin B1/Cdk1 pathway. Several studies have clearly demonstrated that regulation of p27, cyclin D1 and the cyclin E/Cdk2 complex is a principal mechanism through which lapatinib blocks cell cycle progression in cancer cells [21,27].

Many anti-cancer drugs cause cell death through the induction of apoptosis [28,29]. Apoptosis is a regulated physiological process leading to cell death and can be activated through two pathways that include the extrinsic pathway (mediated by death receptors) or the intrinsic pathway (mediated by mitochondria). The intrinsic pathway is generally induced by stimuli such as anticancer drugs. All these signals activate caspases, which in turn cleave various cellular substrates including poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) [30]. During apoptosis, the cleavage of PARP mediated through caspases 3 and 7 is a useful hallmark for cell death [31,32]. Quercetin-3-methyl ether induced apoptosis, accompanied by PARP and caspases 3 and 7 cleavage in both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant human breast cancer cells, whereas lapatinib had no impact on lapatinib-resistant cells. These results suggest quercetin-3-methyl ether indeed overcomes resistance to lapatinib by inducing G2/M arrest and apoptosis. Chk1 plays a role in DNA damage, G2/M transition and apoptosis and is a potential target for cancer therapy [33]. Various agents have been shown to activate Chk1 for treatment of cancer [34]. For example, curcumin induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis in BxPC-3 cells through activation of Chk1 [35]. These studies support the possibility that Chk1 plays an important role in quercetin-3-methyl ether-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.

In conclusion, quercetin-3-methyl ether is able to produce a significant inhibition of cell growth in lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant breast cancer cells, which is associated with changes in the level of factors that regulate cell cycle G2/M progression and apoptosis including cyclin B1, p-Cdc25c (Ser216), Chk1, caspase 3, caspase 7 and PARP. These results suggest that quercetin-3-methyl ether might be a novel and promising natural therapeutic agent in both lapatinib-sensitive and -resistant patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Hormel Foundation and National Institutes of Health NCI Contract Number HHSN-261200433009C - NO1-CN-55006-72.

References

- 1.Germano S, O'Driscoll L. Breast cancer: understanding sensitivity and resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies to aid in personalised medicine. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9(3):398–418. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukohara T. Mechanisms of resistance to anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 agents in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong JH, An JY, Kwon YT, Li LY, Lee YJ. Quercetin-induced ubiquitination and down-regulation of Her-2/neu. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105(2):585–595. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Junttila TT, Li G, Parsons K, Phillips GL, Sliwkowski MX. Trastuzumab-DM1 (T-DM1) retains all the mechanisms of action of trastuzumab and efficiently inhibits growth of lapatinib insensitive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackwell KL, Pegram MD, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Single-agent lapatinib for HER2-overexpressing advanced or metastatic breast cancer that progressed on first- or second-line trastuzumab-containing regimens. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(6):1026–1031. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giampaglia M, Chiuri VE, Tinelli A, De Laurentiis M, Silvestris N, Lorusso V. Lapatinib in breast cancer: clinical experiences and future perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(Suppl 3):S72–S79. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)70024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy MJ, O'Donovan N, Crown J. Use of molecular markers for predicting therapy response in cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoppoli G, Moran E, Soncini D, et al. Ras-induced resistance to lapatinib is overcome by MEK inhibition. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10(2):168–175. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubio S, Quintana J, Eiroa JL, Triana J, Estevez F. Acetyl derivative of quercetin 3-methyl ether-induced cell death in human leukemia cells is amplified by the inhibition of ERK. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(10):2105–2113. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubio S, Quintana J, Lopez M, Eiroa JL, Triana J, Estevez F. Phenylbenzopyrones structure-activity studies identify betuletol derivatives as potential antitumoral agents. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;548(1–3):9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee EH, Kim HJ, Song YS, et al. Constituents of the stems and fruits of Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26(12):1018–1023. doi: 10.1007/BF02994752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeara R, Albuquerque S, Lopes NP, Lopes JL. Trypanocidal activity of Lychnophora staavioides Mart. (Vernonieae, Asteraceae) Phytomedicine. 2003;10(6–7):490–493. doi: 10.1078/094471103322331430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei BL, Lu CM, Tsao LT, Wang JP, Lin CN. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of quercetin 3-O-methyl ether and other constituents from Rhamnus species. Planta Med. 2001;67(8):745–747. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colburn NH, Wendel EJ, Abruzzo G. Dissociation of mitogenesis and late-stage promotion of tumor cell phenotype by phorbol esters: mitogen-resistant variants are sensitive to promotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(11):6912–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Luca A, Faraso S, D’Alessio A, et al. Characterization of human breast cancer cells with acquired resistance to the EGFR/ErbB-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib. AACR AACR 102nd Annual Meeting 2011. 2011 Abstract no. 3581. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eastman A. Cell cycle checkpoints and their impact on anticancer therapeutic strategies. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91(2):223–231. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes JK, Solomon MJ. A predictive scale for evaluating cyclin-dependent kinase substrates. A comparison of p34cdc2 and p33cdk2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(41):25240–25246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobrich M, Jeggo PA. The impact of a negligent G2/M checkpoint on genomic instability and cancer induction. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(11):861–869. doi: 10.1038/nrc2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunner-Kubath C, Shabbir W, Saferding V, et al. The PI3 kinase/mTOR blocker NVP-BEZ235 overrides resistance against irreversible ErbB inhibitors in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Alessio A, De Luca A, Maiello MR, et al. Effects of the combined blockade of EGFR and ErbB-2 on signal transduction and regulation of cell cycle regulatory proteins in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123(2):387–396. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deep G, Singh RP, Agarwal C, Kroll DJ, Agarwal R. Silymarin and silibinin cause G1 and G2-M cell cycle arrest via distinct circuitries in human prostate cancer PC3 cells: a comparison of flavanone silibinin with flavanolignan mixture silymarin. Oncogene. 2006;25(7):1053–1069. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DePinto W, Chu XJ, Yin X, et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of R547: a potent and selective cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor currently in phase I clinical trials. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(11):2644–2658. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye Z, Chen Z, Chen W, et al. XJW20, a novel oxoindole derivative, induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis selectively in K562 leukemia cell line. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;183(1):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguda BD. A quantitative analysis of the kinetics of the G(2) DNA damage checkpoint system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(20):11352–11357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furnari B, Rhind N, Russell P. Cdc25 mitotic inducer targeted by chk1 DNA damage checkpoint kinase. Science. 1997;277(5331):1495–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu I, Blackwell K, Chen S, Slingerland J. The dual ErbB1/ErbB2 inhibitor, lapatinib (GW572016), cooperates with tamoxifen to inhibit both cell proliferation- and estrogen-dependent gene expression in antiestrogen-resistant breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi EJ, Kim GH. Apigenin causes G(2)/M arrest associated with the modulation of p21(Cip1) and Cdc2 and activates p53-dependent apoptosis pathway in human breast cancer SK-BR-3 cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20(4):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu J, Zhang L. Apoptosis in human cancer cells. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(1):19–24. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kliem H, Berisha B, Meyer HH, Schams D. Regulatory changes of apoptotic factors in the bovine corpus luteum after induced luteolysis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76(3):220–230. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Germain M, Affar EB, D'Amours D, Dixit VM, Salvesen GS, Poirier GG. Cleavage of automodified poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase during apoptosis. Evidence for involvement of caspase-7. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(40):28379–28384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371(6495):346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Decker SJ, Sebolt-Leopold J. Knockdown of Chk1, Wee1 and Myt1 by RNA interference abrogates G2 checkpoint and induces apoptosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3(3):305–313. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CY, Hsu YL, Tsai YC, Kuo PL. Kotomolide A arrests cell cycle progression and induces apoptosis through the induction of ATM/p53 and the initiation of mitochondrial system in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(7):2476–2484. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahu RP, Batra S, Srivastava SK. Activation of ATM/Chk1 by curcumin causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(9):1425–1433. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.