Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease of the basal ganglia. Like other adult-onset neurodegenerative disorders, it is without a treatment that forestalls its chronic progression. Efforts to develop disease-modifying therapies to date have largely focused on the prevention of degeneration of the neuron soma, with the tacit assumption that such approaches will forestall axon degeneration as well. We herein propose that future efforts to develop neuroprotection for PD may benefit from a shift in focus to the distinct mechanisms that underlie axon degeneration. We review evidence from human post-mortem studies, functional neuroimaging, genetic causes of the disease and neurotoxin models that axon degeneration may be the earliest feature of the disease, and it may therefore be the most appropriate target for early intervention. In addition, we present evidence that the molecular mechanisms of degeneration of axons are separate and distinct from those of neuron soma. Progress is being made in understanding these mechanisms, and they provide possible new targets for therapeutic intervention. We also suggest that the potential for axon re-growth in the adult central nervous system has perhaps been underestimated, and it offers new avenues for neurorestoration. In conclusion, we propose that a new focus on the neurobiology of axons, their molecular pathways of degeneration and growth, will offer novel opportunities for neuroprotection and restoration in the treatment of PD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: substantia nigra, striatum, α-synuclein, LRRK2, MPTP, WldS, autophagy, Akt, mTor

Parkinson's disease: An introduction and overview of current approaches in experimental therapeutics

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that is second only to Alzheimer's disease (AD) in its worldwide prevalence. Like AD, the principal risk factor is increased age, with incidence rising virtually exponentially after age 50 (Bower et al., 2000, Driver et al., 2009). The striking effect of increasing age, coupled with rising life expectancies in industrialized nations, has led to predictions that the burden of PD will double over the next generation (Driver et al., 2009). Although PD, unlike AD, has benefited from the availability of medical and deep brain stimulation therapies that provide lasting and sometimes dramatic clinical benefits (reviewed in (Lees et al., 2009)), these treatments provide only symptomatic relief that wanes as the disease advances. Furthermore, the treatments currently available for PD do not address the many highly debilitating non-motor manifestations of the disease, including cognitive decline and autonomic failure. Thus, for PD, as for the many other adult-onset neurodegenerative disorders, there is a desperate need for therapies that will forestall the progressive degenerative process. The development of such therapies will ultimately depend on an understanding of the cellular mechanisms responsible.

PD presents clinically with impairment of motor abilities, and diagnosis currently depends on the identification of cardinal features: tremor at rest, rigidity of the limbs, slowness and paucity of voluntary movement (`bradykinesia') and postural instability (a tendency to fall even in the absence of weakness or cerebellar balance disturbance) (Lees et al., 2009). The brain pathology underlying these motor signs is a loss of the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (SN). These neurons project their unmyelinated axons rostrally via the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) to the striatum, where they normally release dopamine. It is this loss of dopamine that results in the characteristic motor signs. Among the surviving neurons of the SN, a hallmark pathologic feature, the Lewy body (LB), can be identified as an intracellular inclusion. LBs contain a variety of cellular proteins, the most abundant being α-synuclein (Spillantini et al., 1997) a protein that normally is abundant in nerve terminals (Iwai et al., 1995, Maroteaux et al., 1988). The discovery that α-synuclein is a LB component was made soon after its identification as the first genetic cause of familial PD (Polymeropoulos et al., 1997). Although definitive diagnosis of PD today depends on identification of the aforementioned motor abnormalities, and the presence of both SN neuron loss and LBs at post-mortem, nevertheless, it has long been recognized that the disease affects other brain systems, both catecholaminergic and non-catecholaminergic (Agid et al., 1987). LBs were first identified, in fact, in the substantia innominata and the dorsal vagal nucleus (Shults, 2006). Furthermore, the disease process is not limited to the brain; Lewy pathology has long been identified in peripheral neuronal structures, including sympathetic ganglia (Rajput and Rozdilsky, 1976), the enteric nervous system (Kupsky et al., 1987, Wakabayashi et al., 1988), the cardiac plexus and the adrenal (reviewed in (Wakabayashi and Takahashi, 1997)). Thus, while the nigro-striatal dopaminergic projection has been the principal focus of most research, it should perhaps be considered a useful “model” system through which we can attempt to understand a disease that is actually systemic in nature.

Since the discovery of disease-causing mutations in α-synuclein in 1997 (Polymeropoulos et al., 1997), subsequent discoveries of other genetic causes of PD have had a major impact on current research on pathogenesis. The full range of these discoveries lies beyond the current review, but includes the discovery of mutations in leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) (Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2004, Zimprich et al., 2004), which, like α-synuclein, causes an autosomal dominant form of PD, and mutations in parkin (Kitada et al., 1998), DJ-1 (Bonifati et al., 2003), and PINK1 (Valente et al., 2004), all of which cause autosomal recessive forms of the disorder (reviewed in (Shulman et al., 2011)). These discoveries have generated a wealth of important research directions. For the most part, however, this ongoing work has given little consideration to the specific and distinct roles that mutant proteins may play in the separate compartments of living neurons: the soma, dendrites and axons.

One truism in devising neuroprotective strategies is that the earliest pathologic events should be targeted so that later degenerative consequences can be avoided. To date, the concept of neurodegeneration that has prevailed in the design of clinical trials has exclusively focused on the death of the neuron, and neuroprotection has been equated with the rescue of the neuron soma. In this concept there is the tacit assumption that death of the neuron soma either precedes or occurs at the same time as the degeneration of the axon, and thus strategies protecting the neuron soma would be expected to protect axons as well. However, what if axons degenerate first? If so, then efforts to protect the neuron soma would be a “too little, too late” approach. Here we will review the evidence that the earliest detectable pathology in PD is at the level of the axons, not the neuron soma. Furthermore, this prevailing concept of neurodegeneration makes the additional assumption that the mechanisms underlying neuron soma and axon degeneration are the same. Only if such were the case would a therapeutic strategy that is intended to protect the neuron soma provide axonal protection as well. However, there is a great deal of evidence to indicate that the mechanisms of neuron soma and axon degeneration are separate and distinct (Finn et al., 2000, Raff et al., 2002). Support for the notion that these mechanisms are distinct comes in large part from the unique phenotype of the Wallerian degeneration slow (WldS) mouse. In this review, therefore, we will provide an overview of the biology of this mutant as it relates to axon degeneration in the nigro-striatal projection. As additional evidence of the distinct cellular mechanisms of axon destruction we will also summarize recent observations that suggest a role for macroautophagy in retrograde axonal degeneration in this projection. We will close by sharing our thoughts on the potential implications of this new suggested focus on the distinct mechanisms of axon degeneration in experimental therapeutics.

Striatal dopaminergic terminal loss is an early and dominant feature of PD

In recent years, there has been a great deal of debate over the question of “Where does PD begin?” The answer to this question is of course critical to the development of strategies for pre-clinical detection and early diagnosis, and it is also critical to concepts of pathogenesis. However, this debate has centered around regional studies of α-synuclein pathology in the post-mortem brain (Braak et al., 2003). Very briefly, it has been proposed that the disease, when it occurs in brain, first affects the olfactory tubercle or the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, and thereafter spreads into other brain regions. While this debate has yet to be resolved (Burke et al., 2008), it is not in any case the focus of our interest here. We seek instead to ask where does the disease begin at the cellular level. If it does first manifest in neurons, as widely believed, then in which compartment? Years ago, Dr. Oleh Hornykiewicz, the discoverer of dopamine deficiency in PD (Ehringer and Hornykiewicz, 1960), proposed, on the basis at the cellular localization of the dopamine transporter, the possibility “…that the dopamine neuron death in PD is a dying-back degeneration … considering that the dopamine transporter is particularly enriched in the striatal terminals rather than on substantia nigral cell bodies” (Hornykiewicz, 1998). We propose here that this concept of an early axonal terminal degeneration in PD receive renewed consideration, based not only on a full, contemporary assessment of human post-mortem and functional imaging studies, but also on recent evidence related to the cellular site of action of disease-causing mutations.

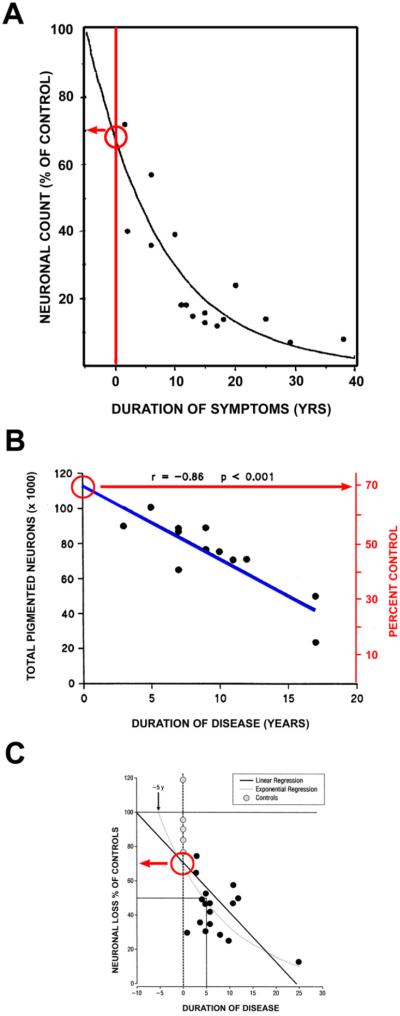

There have been many studies of the magnitude of SN dopamine neuron loss, and that of striatal terminal loss, at the onset of PD, making it possible to compare the degree of early pathology in these two cellular compartments. Fearnley and Lees (Fearnley and Lees, 1991) performed a regression analysis of neuron counts versus duration of PD and found that the number of neurons lost at time of symptom onset is 31%, adjusted for age (Fig 1A). This estimate is compatible with their observation that individuals with incidental Lewy bodies (ILB), who may represent pre-clinical cases of PD, showed a mean 27% age-adjusted loss without manifest motor signs. Subsequent quantitative morphologic studies have supported this estimate. Using a dissector approach, Ma and colleagues examined the relationship between total number of pigmented neurons in SN and duration of disease (Fig 1B) and found that symptom onset would be predicted to occur at 30% loss relative to age-matched control values (Ma et al., 1997). Greffard and colleagues likewise found that by either a linear or exponential regression, there is about a 30% loss of neurons in comparison to age-matched controls at the time of the appearance of motor signs (Greffard et al., 2006). Thus, there is a good consistency in the available data to suggest that the motor signs of PD appear when there is about a 30% loss of total SN neurons in comparison to age-matched controls.

Fig. 1.

Estimates of loss of SN dopamine neurons at the time of PD symptom onset. (A) Fearnley and Lees (Fearnley and Lees, 1991) examined the number of pigmented neurons in the SN in relation to duration of symptoms, and performed a regression analysis based on an exponential decline in their number. They estimated about a 30% total loss, adjusted for age. (B) A similar estimate can be derived from the data of Ma and colleagues, based on their dissector counts of pigmented SN neurons (Ma et al., 1997). A linear regression analysis of their data with extrapolation to time of disease onset yields an estimate of about a 30% loss. (C) Greffard and colleagues performed counts of neurons in the SNpc, and determined density per unit volume. By either a linear or a negative exponential best fit analysis, they estimated a 30% loss at the time of symptom onset (Greffard et al., 2006). (Figure modified from (Cheng et al., 2010)).

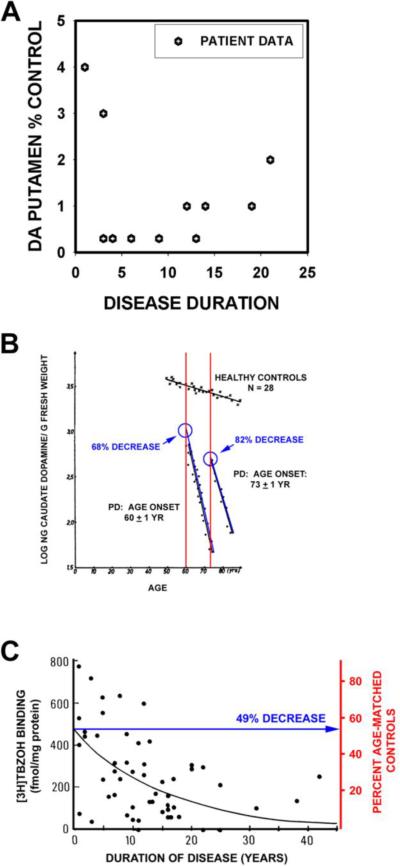

Estimates of the extent of striatal dopaminergic terminal loss at the time of disease onset have been based on post-mortem neurochemical studies and functional imaging studies in vivo. The work of Bernheimer and colleagues (Bernheimer et al., 1973) is often cited in support of the statement that Parkinson motor signs first appear when about 80% of striatal or putaminal dopamine is lost (Dauer and Przedborski, 2003, Marsden, 1990). However, the Bernheimer study does not provide useful information for this estimate. Only 39 of the 64 patients studied had PD, and among them only 13 had dopamine measured in brain. There was no analysis of dopamine content as a function of disease duration, or a regression analysis. The data provided are too few and variable for this purpose (Fig 2A) (Cheng et al., 2010). Subsequently, Riederer and Wuketich analyzed post-mortem data for caudate dopamine in relation to disease onset (Riederer and Wuketich, 1976). They studied two cohorts: one consisting of patients with disease onset at 60 years, and a second consisting of patients with onset at 73 years. As shown in Figure 2B, extrapolation to time of onset reveals a 68% and 82% decrease, respectively, in caudate dopamine for these two groups in relation to age-matched controls.

Fig. 2.

Estimates of loss of striatal dopamine terminal markers at time of symptom onset. (A) A graphical representation of the data presented in the oft-cited Bernheimer study to support the statement that there is an 80% reduction at the time of disease onset (Bernheimer et al., 1973). In the Bernheimer study, only 13 brains from patients with a diagnosis of PD were subjected to biochemical analysis. No regression analysis was performed. (B) Reiderer and Wuketich (Riederer and Wuketich, 1976) measured caudate dopamine content in two PD cohorts, one with an age of onset at 60 ± 1 years, and a second at 73 ± 1 years. Back extrapolation indicates a 68% and an 82% decrease, respectively, in caudate dopamine at the time of onset of disease in the two groups. (C) Scherman and colleagues analyzed [3H]TBZOH binding to the vesicular monoamine transporter in post-mortem caudate nucleus of 54 PD patients (Scherman et al., 1989). Polynomial regression analysis indicated a loss of 49% of binding sites at time of disease onset. (Figure modified from (Cheng et al., 2010)).

Post-mortem studies of dopamine may be subject to concerns about the effects of post-mortem delay. Measurements of vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) binding sites with tritiated α-dihydrotetrabenazine ([3H]TBZOH) help to address these issues (Scherman et al., 1989). Scherman and colleagues analyzed [3H]TBZOH binding in post-mortem caudate in PD patients and controls, and concluded that motor signs become apparent when there is about a 50% decrease relative to the levels at the average age of disease onset (Fig 2C).

A concern about comparing data for SN neuron loss to these neurochemical measures of striatal terminal loss is that while counts of remaining neurons in the SN are not likely to be altered by factors affecting the quality of post-mortem tissue preservation, biochemical assessments may be. Concern may therefore be raised that the greater apparent losses of striatal dopaminergic markers than SN neurons in these studies may be an artifact due to the analysis of postmortem tissues. It is therefore worthwhile to consider radioligand imaging analysis of striatal dopaminergic markers obtained in vivo. Numerous imaging studies have examined the relationship between striatal dopaminergic marker loss and onset of motor signs. We will consider only those studies that have used either a regression analysis with extrapolation to time of disease onset, or, alternatively, have studied patients with unilateral PD (i.e., Hoehn and Yahr stage I) and have compared the degree of loss for the unaffected side to that of the affected side (Table). Among these studies, three types of radioligand have been used: [18F] dopa to assess levodopa metabolism, ligands for the dopamine transporter, or ligands for the vesicular monoamine transporter (see Nandhagopal et al for review (Nandhagopal et al., 2008)). Estimates of dopamine terminal loss at time of disease onset are less for those obtained with [18F] dopa (20–50% in putamen) than for those obtained with the other ligands (50–70% in putamen) due to a compensatory upregulation of aromatic acid decarboxylase (Lee et al., 2000). If we therefore restrict our attention to losses assessed by the other ligands, the estimates of 50 to 70% correspond fairly well to the estimates of about 50% loss based on the post-mortem studies of [3H]TBZOH (see Fig 2) (Scherman et al., 1989).

TABLE.

PD Imaging Studies of Striatal or Putaminal Dopaminergic Deficits at Time of Symptom Onset

| AUTHOR | YEAR | N | MODALITY | LIGAND | STRIATUM (% LOSS) | PUTAMEN (% LOSS) | ANALYSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPAMINE TRANSPORTER BINDING | |||||||

| Tissingh et al | 1998 | 8 (HY I) | SPECT | [123I]β-CIT | 39–51 | 51–64 | HY I (IPSI vs CONTRA) |

| Lee et al | 2000 | 13 (HY I) | PET | [11C]MP | --- | 56–71 | HY I (IPSI vs CONTRA) |

| Schwartz et al | 2004 | 6 | SPECT | [123I]IPT | 43 | 56 | REGRESSION |

| VESICULAR MONOAMINE TRANSPORTER BINDING | |||||||

| Lee et al | 2000 | 13 (HY I) | PET | [11C]DTBZ | 51–62 | HY I (IPSI vs CONTRA) | |

In each study, the degree of dopaminergic terminal loss in whole striatum or putamen was determined either by regression analysis with back extrapolation to Time = 0, or by determination of the loss on the side ipsilateral (IPSI) to symptoms in comparison to the side contralateral (CONTRA) to symptoms in patients with unilateral PD (Hoehn and Yahr Stage I (HY I)). β-CIT: 2β-carbomethoxy-3 β -(4-iodophenyl); MP: methylphenidate; IPT: N-(3-iodopropene-2-yl)-2β - carbomethoxy-3β - (chlorophenyl); DTBZ: dihydrotetrabenazine.

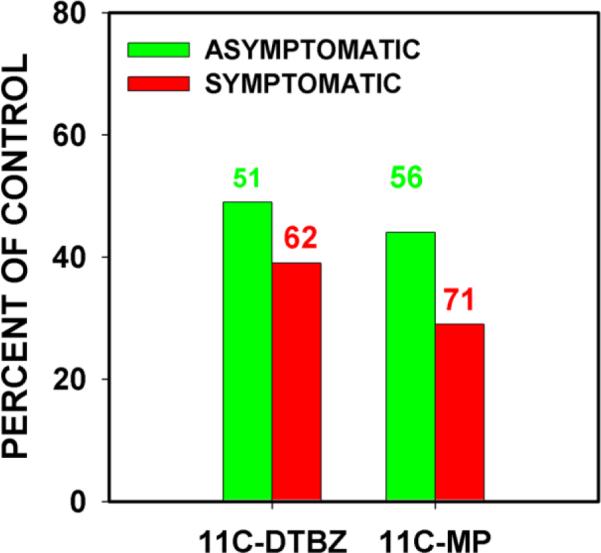

Studies by the Stoessel group serve to illustrate these findings. In the Lee et al study (Lee et al., 2000), PD patients with early unilateral (HY Stage I) motor signs were evaluated by PET imaging. These patients provide a unique opportunity to determine the `window' of striatal dopamine terminal loss within which motor signs will appear. In these patients, signs appeared between a loss of 51 and 62% for a vesicular monoamine transporter ligand (11C-DTBZ) and between 56 and 71% for a dopamine transporter ligand (11C-MP) (Fig. 3). More recently, this group has shown that the extent of loss of DTBZ binding at the time of disease onset depends on age; for younger patients, onset occurred at 71% loss of DTBZ (Fuente-Fernandez et al., 2011).

Fig. 3.

In patients with unilateral parkinsonism, motor signs do not yet appear when striatal dopaminergic terminal markers are depleted only 51% for 11C-DTBZ or 56% for 11C-MP (green bars), but appear on the affected side when these markers are depleted 62% and 71% respectively (red bars). (The data shown are from (Lee et al., 2000).

In conclusion, assessment of available data suggests that at the time of motor symptom onset the extent of loss of striatal or putaminal dopaminergic markers exceeds that of SN dopamine neurons. This conclusion is consistent with observations that, at the time of death, depending on disease duration, while there has been 60–80% loss of SN dopamine neurons (Fearnley and Lees, 1991, Pakkenberg et al., 1991), there has been a much more profound loss of striatal or putaminal dopaminergic markers (Bernheimer et al., 1973, Kish et al., 1988, Scherman et al., 1989)).

Axon degeneration in genetic causes of PD

Although missense mutations in α-synuclein are a rare cause of PD (Kruger et al., 1998, Polymeropoulos et al., 1997, Zarranz et al., 2004), its neurobiology is central to current PD research. Of great significance was the discovery that not only are familial forms of the disease caused by missense mutations, but also by increased expression of wildtype due to triplication or duplication mutations (Farrer et al., 2004, Singleton et al., 2003). Furthermore, there is evidence that polymorphisms in the promoter region for α-synuclein are associated with increased risk for the disease (Pals et al., 2004). In addition, as previously mentioned, α-synuclein is a major protein component of LBs (Spillantini et al., 1998) and Lewy neurites. With the use of sensitive antibodies to α-synuclein, it has become easier to detect LBs in neuron cell bodies and Lewy pathology in adjacent neurites. When effort is made to seek α-synuclein pathology in axons, by use of refined immunohistochemical procedures (Braak et al., 1999) or unique immunoreagents (Duda et al., 2002, Galvin et al., 1999), it is readily observed. Strikingly, by use of a novel paraffin-embedded tissue blot technique, in which tissue sections are subjected to pre-digestion, the greatest abundance of α-synuclein aggregates is found not in cell bodies, but in the neuropil (Kramer and Schulz-Schaeffer, 2007) in dementia with Lewy Body (DLB) brains. Furthermore, these studies show that the preponderance of α-synuclein small aggregates in DLB brains are entrapped within pre-synaptic terminals (Kramer and Schulz-Schaeffer, 2007). Thus, there is evidence that α-synuclein pathology is abundant in axons and pre-synaptic terminals, consistent with the observation that its normal localization is predominantly in pre-synaptic terminals.

There have been few studies attempting to determine the sequence of development of α-synuclein pathology at the cellular level in neurons. However, Orimo and colleagues have exploited the known propensity of PD to affect peripheral autonomic neurons and their axons to explore the timing of events (Orimo et al., 2008). Based on patterns of α-synuclein pathology and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining in cardiac sympathetic axons and ganglia in patients with PD, they conclude that the disease process begins in the distal axon and proceeds retrograde.

The possibility that the disease-related effects of α-synuclein first occur at pre-synaptic terminals is supported by experimental studies. In a mouse transgenic model based on expression of a truncated form of α-synuclein (α-synuclein (1–120)), while no loss of dopamine neurons occurs, there is the appearance of striatal dopaminergic axon pathology (Tofaris et al., 2006). In these mice, this pathology is accompanied by an age-dependent re-distribution of synaptic proteins and a reduction of dopamine release (Garcia-Reitbock et al., 2010). Volpicelli-Daley and colleagues have demonstrated in primary neuronal culture that exogenous recombinant α-synuclein fibrils can be taken up and induce intra-neuronal aggregation of endogenous α-synuclein. They clearly demonstrate that the first locus of formation of synuclein aggregates is the pre-synaptic terminal, with subsequent propagation to the neuron soma. Additionally, this pathology is associated with reductions in synaptic proteins (Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2011).

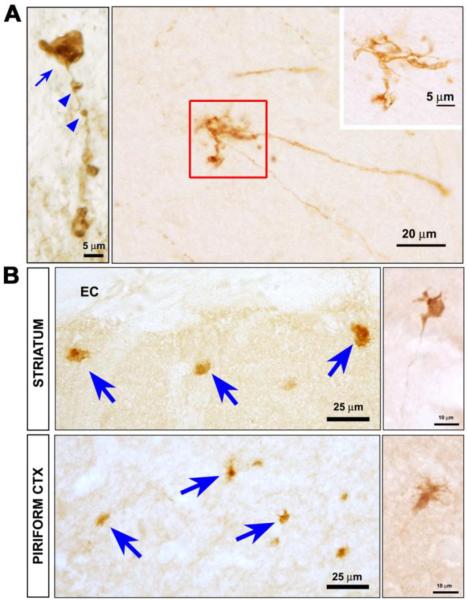

The most common genetic cause of typical PD are mutations in the gene for leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) (Greggio and Cookson, 2009). Recent observations in a mouse model of this genetic form of PD suggest that it may also begin with involvement of axons. This transgenic model was created with a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) carrying the entire human LRRK2 gene, modified to contain the disease-causing R1441G mutation (Li et al., 2009). These mice show the development of an age-related hypokinesia by 9–10 months that is reversible by treatment with levodopa. There is no loss of mesencephalic dopamine neurons, but pathology is observed in dopaminergic axons. TH immunoreactive axons are fragmented, associated with axonal spheroids, and they form dystrophic neurites (Li et al., 2009) (Fig. 4A). These abnormal axonal features are also observed by staining for abnormally phosphorylated tau (Fig 4B). Other evidence also supports the possibility that LRRK2 plays an important role in the regulation of neurite growth and integrity. MacLeod and colleagues have reported that mutant forms of LRRK2 induce decreases of neurite length in primary neuron culture (MacLeod et al., 2006). Similar observations were made for the LRRK2(G2019S) mutant in neuronally differentiated neuroblastoma cells (Plowey et al., 2008) and in primary neurons derived from transgenic mice (Parisiadou et al., 2009). The molecular basis of these effects is not known, but of potential interest in this regard is the identification of moesin, and the closely allied proteins ezrin and radixin, as possible LRRK2 substrates (Jaleel et al., 2007). These proteins have been implicated in the regulation of neurite outgrowth (Paglini et al., 1998). The ability of LRRK2 to regulate the phosphorylation status of these proteins, and the closely correlated degree of neurite growth, has also been observed in primary cultures (Parisiadou et al., 2009).

Fig. 4.

Axonopathy in hLRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice. (A) At the single axon level, staining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) reveals fragmentation (blue arrowheads), axonal spheroids (blue arrow), and dystrophic neurites at axon terminals (red square and inset). (B) Axonal abnormalities in the striatum and piriform cortex of the transgenic mice are also revealed by immunostaining for phosphorylated tau. Spheroids (blue arrows) and dystrophic neurites (side panels) similar to those visualized by TH staining, are observed. (Images adapted from Li et al (Li et al., 2009)).

Thus, based on analysis of the predominant site of pathology in PD at its onset, and evidence from autosomal dominant genetic forms of the disease, it is reasonable to hypothesize that axon dysfunction may be an early feature of PD.

Axon degeneration in a neurotoxin model of PD: MPTP

Although widely used as an environmental toxicity model of dopaminergic cell death, the molecular mechanisms underlying MPTP`s (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) mode of action are still not fully understood. However, one striking similarity between MPTP effects and those seen in post-mortem studies and genetic models of PD is the pronounced degeneration of dopaminergic axons. For example, using an acute MPTP administration model in cynomolgus monkeys, Herkenham et al. (Herkenham et al., 1991) observed marked reductions of dopaminergic axons prior to the loss of nigral cell bodies. In macaques, Meissner et al. (Meissner et al., 2003) reported an 80% loss of both the dopamine plasma membrane transporter and dopamine levels in the striatum following chronic MPTP delivery whereas only a 43% loss of TH-labeled cells was observed in the substantia nigra. Thus patients diagnosed with PD as well as non-human primate MPTP models exhibit a loss of striatal dopaminergic terminal fields that exceeds the loss of nigral cell bodies.

Consistent with findings from non-human primate models, dopaminergic terminal loss is also observed over an earlier time frame and in a more pronounced fashion than cell body loss in murine MPTP models. Using a chronic MPTP treatment schedule, Serra and colleagues (Serra et al., 2002) showed that one day after MPTP treatment, striatal dopamine levels were diminished by 60% whereas at this same time point no TH immunoreactive cell bodies were lost in the substantia nigra. Li and colleagues (Li et al., 2009) also showed that MPTP-induced axonal degeneration preceded cell death. These investigators used both an acute and a chronic MPTP treatment plan and in either case observed about a 25% cell body loss one week after cessation of injections whereas TH terminals were decreased by ~64 and 70% in either the acute or chronic PD model respectively. Similarly, a recent study looking at the effect of GDNF/Ret signaling following 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) or MPTP treatment, found that in either case a profound decrease in dopamine was observed in the striatum (73%) whereas only a 9% decline of cells in the substantia nigra was observed. These data not only re-confirm the basic observation that axons are compromised before cell bodies but also re-enforce the notion that axons and cell bodies constitute separate compartments since the presence of the GDNF receptor, RET, rescued the cells but not the terminal fields (Mijatovic et al., 2011). Finally, using an antibody devised against an extracellular epitope of the dopamine transporter, Muroyama et al., (Muroyama et al., 2011) prepared MPTP-treated and non-treated synaptosomal preparations to show that chronically administered MPTP rapidly decreased this critical protein at time points when cell bodies are typically intact. Taken together, there is a remarkable consistency across species and studies that MPTP-impaired terminal fields occur earlier than compromised cell bodies. These findings support the hypothesis that nigral neurons degenerate through a “dying back” axonopathy in which degeneration begins in the distal axon and proceeds over weeks or months towards the cell body (Iseki et al., 2001, Raff et al., 2002).

MPTP Mode of action

What are the underlying mechanisms by which MPTP or its toxic metabolite 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) leads to axonal dysfunction? There are many important hypotheses to consider.

Complex I dysfunction

A compelling role for mitochondrial dysfunction comes from a variety of toxin studies suggesting that MPP+ blocks Complex I activity (Bueler, 2010). Complex I deficiency, in turn, leads to reactive oxygen species, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), loss of ATP, and eventually cell death (Chan et al., 2010, Surmeier et al., 2010). Studies over-expressing the yeast single subunit NADH dehydrogenase gene, Ndl 1, support an obligatory role for Complex I activity in mediating the toxic effects of MPP+ since the yeast gene is able to rescue cells or mice from toxin treatment (Marella et al., 2008, Richardson et al., 2007, Sherer et al., 2003). A caveat to the Complex I hypothesis, however, comes from recent data showing that dopaminergic neurons obtained from animals deficient for the Ndufs4 subunit of Complex I still die when treated with MPP+ (Choi et al., 2008). These data suggest that Complex I dysfunction might not be as tightly correlated with MPP+ toxicity as previously suspected.

Redistribution of vesicular dopamine

MPP+ also serves as a substrate for the vesicular monoamine transporter, VMAT2, whereby it enters dopaminergic vesicles leading to the cytoplasmic release of neurotransmitter (see (Lotharius and O'Malley, 2000)). Cytoplasmic dopamine, in turn, is readily oxidized into quinone species that, like mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, may also contribute to the disruption of important cellular processes including axon function (Hastings, 2009). Although reduced dopamine levels attenuate MPP+-induced cell death in dissociated dopaminergic cultures (Lotharius and O'Malley, 2000)., either genetically manipulating (dopamine deficient animals) or pharmacologically manipulating (alpha methyl tyrosine) dopamine levels in vivo did not protect nigral neurons or their terminal fields from MPTP toxicity. Therefore while (Hasbani et al., 2005) re-distributed dopamine might affect cellular processes in certain paradigms, it appears to play less of a role in in vivo MPTP models.

Microtubule dysfunction

Studies have also shown that MPP+ not only inhibits Complex I activity and redistributes vesicular dopamine but it also de-polymerizes microtubules leading to axon fragmentation and decreased synaptic function (Cappelletti et al., 1999, Cappelletti et al., 2005, Cartelli et al., 2010). Over a decade ago, Cappelletti and colleagues (1999) showed that MPP+ affected microtubule assembly in vitro. Using purified microtubule preparations, these investigators then reported that MPP+ bound specifically to tubulin in an almost one to one fashion (Cappelletti et al., 2005). In doing so MPP+ led to the increased probability that the microtubules would shrink, not grow. Recently, Cartelli et al (Cartelli et al., 2010) confirmed and extended these results showing that MPP+ led to microtubule impairment in the pheochromocytoma cell line PC12. This in turn led to a disruption in mitochondrial trafficking in nerve growth factor-induced neuritic processes and caspase 3 activation in cell somas (Cartelli et al., 2010). MPP+-mediated microtubule disruption is also observed in bona fide dopamine neurons. For example, (Kim-Han et al., 2011) used live cell imaging to determine the time course of MPP+ effects on fluorescently-tagged tubulin in dopaminergic axons. These studies noted signs of microtubule disruption (beading) as early as three hours after MPP+ treatment and complete fragmentation after six hours (Kim-Han et al., 2011). Inasmuch as other environmental toxins such as rotenone also destabilize microtubules in dopaminergic neurons (Choi et al., 2011), microtubule disassembly has emerged as an important model underlying axonal dysfunction in PD.

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Neurons are particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction given their long extended processes and high energy demand. Not only does axonal trafficking require energy (maintaining microtubule tracks, the movement of kinesin and dynein motors, loading cargos, etc.) but also factors that lead to a prolonged loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) will trigger autophagy (mitophagy), a process by which damaged mitochondria are marked for repair or destruction. Typically, this would result in a depolarized mitochondria no longer being trafficked down the axon but instead being returned to the cell body (Twig and Shirihai, 2011). If significant numbers of mitochondria are no longer being trafficked to the synapse where energy requirements are high, then the ability of the axon to maintain itself will be compromised and a dying back process may be initiated.

Recently Kim-Han et al (Kim-Han et al., 2011) modified a compartmented chamber device to specifically monitor organelle movement in dopamine axons before and after MPP+ treatment. Using transgenic GFP-tagged mice that target dopamine neurons, it was discovered that MPP+ rapidly (<30 min) and selectively decreased mitochondrial movement in dopamine but not non-dopamine axons. In support of the notion that damaged mitochondria are re-routed to the cell body for disposal, anterograde traffic was decreased whereas retrograde trafficking was increased. Surprisingly, MPP+ effects were not dependent upon ATP, calcium, or reactive oxygen species but instead were dependent upon redox potential (Kim-Han et al., 2011). Direct effects of MPP+ on axonal transport have also been seen in the isolated squid axoplasm (Morfini et al., 2007, Serulle et al., 2007). Similar to the murine dopaminergic axon, MPP+ decreased anterograde trafficking while increasing retrograde movement (Morfini et al, 2007) whereas in the squid all organelles and vesicles were affected versus only mitochondria in the mouse (Kim-Han et al., 2011). In neither system were microtubule tracks affected, at least in the time frame of the experiments. Taken together, these data stress the importance of axonal trafficking and in particular the consequences of not getting mitochondria to where they need to go. Redistribution of mitochondria away from sites of high energy usage would lead to axonal impairment, loss of synaptic connectivity, and subsequently, loss of function.

What makes dopamine axons so vulnerable?

Why are dopamine axons more vulnerable than axons from other types of nerve cells? One hypothesis is always the neurotransmitter itself. Given dopamine's propensity to become oxidized within the cytoplasmic milieu (Hastings, 2009), any process that prevents uptake or redistributes dopamine from the safety of the vesicle will lead to potentially injurious levels of reactive oxygen species that affect many cellular processes including bioenergetics, microtubule stability, trafficking of organelles, and autophagy to name but a few processes. Indeed, the recent finding by Xia and colleagues (Choi et al., 2011) supports the notion that microtubule disassembly leads to redistributed dopamine, reactive oxygen species and then cell death. While this may occur in response to rotenone, the in vivo data from the dopamine deficient animals argues against a prominent role for dopamine in MPTP-treated mice (Hasbani et al., 2005). Moreover, as many investigators have pointed out, L-Dopa therapy per se does not accelerate the disease process (Fahn, 2005), and there is considerable vulnerability amongst dopamine neurons underscoring the notion that other aspects of dopamine neurons may play a greater role.

Recent data from two independent groups have found that dopaminergic mitochondria are only 40% of the size of non-dopaminergic mitochondria (Kim-Han et al., 2011, Liang et al., 2007). In addition, mitochondria in dopaminergic axons are almost three times slower than mitochondria from non-dopaminergic axons (Kim-Han et al., 2011). Because dopaminergic terminal fields can be far more extensive than those of other neurotransmitter types (Matsuda et al., 2009), when challenged, dopaminergic axons might be less effective at getting mitochondria to where they need to be, when they need to be there. The elegant anatomical studies of Matsuda and colleagues vividly reveal the magnitude of this task (Matsuda et al., 2009). They estimate that the terminal arborizations of single SN dopamine neurons extend throughout 2.7% of the total striatal volume and influence approximately 75,000 striatal neurons. It is apparent from inspection of their complete demonstrations of the entire striatal arborization systems of single dopamine neurons that the neuron soma itself represents only a small fraction of the total cellular volume of these neurons. Taken together, any of these processes, microtubule disassembly, mitochondrial dysfunction, induction of autophagy, and reactive oxygen species, can lead to axonal trafficking problems, dysfunction, and then degeneration. Once the connection is broken, saving the cell body is a moot issue. Thus therapeutic efforts might be most efficacious if they are re-directed towards maintaining connections versus saving the cell body.

Mechanisms of axon degeneration WldS

The most striking evidence that axons can survive even in the presence of destruction of the neuronal soma derives from observations made in the WldS mouse (Coleman and Perry, 2002). This mutation arose spontaneously in C57Bl/6 mice, and it was demonstrated to cause delayed Wallerian degeneration in peripheral nerve after axotomy (Lunn et al., 1989). WldS can delay axonal degeneration about ten-fold from a wide variety of genetic and toxin-inducing stimuli both in vivo and in vitro (Coleman and Freeman, 2010, Feng et al., 2010). WldS is a chimeric protein composed of the N-terminal 70 amino acids of the ubiquitination factor Ube4b followed by a 18 amino acid linker region and the entire sequence of Nmnat1, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of NAD+ (Mack et al., 2001). Most studies suggest that catalytically active Nmnat1 is necessary for axonal protection (Avery et al., 2009, Conforti et al., 2009), although it is unclear whether increased NAD+ is responsible (Sasaki et al., 2009). Despite WldS being primarily localized in the nucleus, subcellular localization studies have found substantial amounts of WldS within the mitochondrial matrix where it may enhance ATP synthesis (Yahata et al., 2009), prevent free radical formation (Press and Milbrandt, 2008), and/or maintain mitochondrial membrane potential (Ikegami and Koike, 2003).

WldS also effectively blocks axon degeneration in animal models of PD (Cheng and Burke, 2010, Hasbani and O'Malley, 2006, Sajadi et al., 2004). In the MPTP murine model WldS animals showed a dramatic protection of dopaminergic fibers (~85%) compared with wild type animals as well as three-fold greater dopamine levels (Hasbani and O'Malley, 2006). These results raise the possibility of protecting axons in early disease stages so as to prevent further loss of striatal dopamine and possibly delay or even prevent the onset of symptoms. Thus identifying how WldS protects dopamine axons from injury has enormous potential for the discovery of novel therapies to stop or slow disease progression.

Although previous studies have suggested that WldS is restricted to the nucleus, new data demonstrate that the WldS protein can be found in the matrix of axonal mitochondria (Yahata et al., 2009). Conceivably, from its position within the mitochondria, WldS modulates a critical process such as fusion/fission dynamics, bioenergetics, or induction of mitophagy. Recently, Barrientos et al (Barrientos et al., 2011) observed that blocking the mitochondrial permeability transition pore rescued sciatic and optic nerve preparations from Wallerian degeneration. These investigators placed WldS upstream of the transition pore, preventing its opening and the ensuing cascade of mitochondrial depolarization, reactive oxygen species production, and ATP depletion leading to axon degeneration and ultimately cell death (Barrientos et al., 2011). In this scenario, WldS acts much like CyclosporinA in preventing the permeability transition pore from opening (Barrientos et al., 2011).

Given the protective effect of WldS on dopaminergic terminal fields following MPTP treatment in vivo, we are using the dissociated dopaminergic culture model to understand the cellular mechanisms underlying terminal field rescue. To date we have found that, like in vivo, WldS rescues dopaminergic neurites from MPP+ treatment (Antenor-Dorsey, unpublished observation). When crossed with TH/GFP mice, WldS prevents MPP+-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial transport potentially by preventing membrane depolarization (Antenor-Dorsey, unpublished results). Thus WldS might prevent axonal dysfunction by altering 1) the fusion/fission equilibrium, 2) depolarization, or 3) small, depolarized mitochondria from being tagged for mitophagy.

Mechanisms of dopaminergic axon degeneration: Macroautophagy

The proposal that canonical mediators of programmed cell death do not play a role in axon degeneration received its first substantial support from the observations of Finn and colleagues who noted that caspase-3 is not activated in a variety of models of axon degeneration (Finn et al., 2000). These observations are not universal, however, because activation of caspases during axon degeneration has been observed in some contexts, particularly in developmental models (El-Khodor and Burke, 2002, Nikolaev et al., 2009, Ries et al., 2008). Nevertheless, in keeping with the observations of Finn and colleagues, many experimental studies in neurotoxin models of PD have shown that anti-apoptotic approaches effectively protect the neuron soma but not the dopaminergic axons (Chen et al., 2008, Eberhardt et al., 2000, Hayley et al., 2004, Ries et al., 2008).

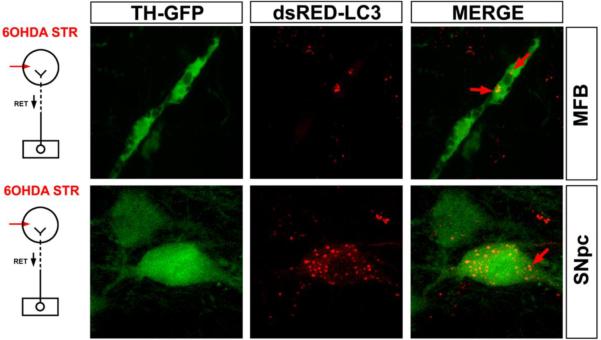

Based on these prior observations, we noted with interest the ability of a constitutively active form of survival signaling kinase Akt (myristoylated-Akt (Myr-Akt), best known for its anti-apoptotic effects, to preserve dopaminergic axons in the highly destructive 6-OHDA intra-striatal injection model (Ries et al., 2006). We had shown in this model that axon degeneration proceeds retrogradely over several days, and does not involve activation of either caspase-3 or calpain (Ries et al., 2008). In order to monitor the acute degeneration of axons, we utilized visualization of axonal GFP florescence in the MFB of TH-GFP mice by use of confocal microscopy (Cheng et al., 2011). Visualization of axons by immunohistochemistry for dopaminergic markers, such as tyrosine hydroxylase, cannot be used to monitor acute degeneration, because axons lose their expression of these phenotypic proteins shortly after injury (see Cheng et al for further detail (Cheng et al., 2011)). Utilizing confocal optical sectioning of the MFB in TH-GFP mice, we found that Myr-Akt expression in dopamine neurons, mediated by adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene transfer, did indeed suppress acute, retrograde axon degeneration induced by 6-OHDA (Cheng et al., 2011). This protective effect was not due to a primary blockade of 6-OHDA toxicity because Myr-Akt demonstrated the same protective effect in an axotomy model.

To explore the mechanisms underlying this protective effect, given the evidence that caspases and calpains were not involved, we initially sought evidence for the occurrence of macroautophagy, because it had previously been implicated in axon degeneration in several in vitro studies (Larsen et al., 2002, Yang et al., 2007). By ultrastructural analysis, we identified numerous autophagic vacuoles (AVs) in striatal neuropil following intra-striatal 6-OHDA (Cheng et al., 2011). The presence of AVs was also identified at the light microscope level in dopaminergic neurons and axons by use of TH-GFP mice in which SN neurons had been transduced with AAV dsRed-LC3 (Fig. 5). Using this approach, we established that Myr-Akt diminished the number of AVs following 6-OHDA treatment. Akt signals through numerous cellular pathways, but the principal pathway involved in suppression of autophagy is through phosphorylation and inhibition of the tuberous sclerosis complex (Jung et al., 2010). This inhibition relieves suppression of the GTPase Rheb, which in turn activates the mTORC1 kinase, a negative regulator of autophagy (Foster and Fingar, 2010, Huang and Manning, 2009, Laplante and Sabatini, 2009). Supporting evidence for a role in Rheb/mTORC1 signaling in mediating axon protection was demonstrated by the ability of a constitutively active form of Rheb, hRheb(S16H) (Yan et al., 2006) to achieve protection comparable to that of Myr-Akt (Cheng et al., 2011).

Fig. 5.

Autophagy occurs in dopaminergic neuron cell bodies and axons following intra-striatal 6-OHDA injection. The presence of AVs in dopaminergic axons and cell bodies is identified by dsRed-LC3 labeling in TH-GFP mice. In the top panels, two clusters of AVs (red arrows) are identified in a GFP-labeled dopaminergic axon in the MFB at 2 days following intra-striatal 6-OHDA. AVs are also observed in dopaminergic cell bodes in the SNpc, shown in the lower panels. A single example is identified by a red arrow. (Images modified from (Cheng et al., 2011)).

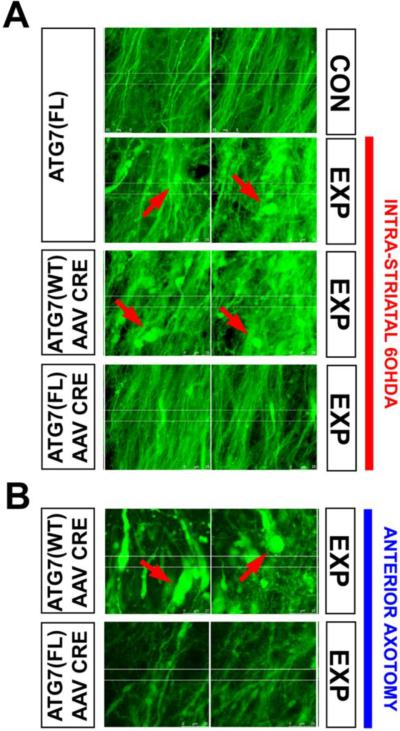

Like Akt, mTORC1 has numerous cellular targets, so to identify a role for suppression of macroautophagy in mediating axon protection, we took a more direct approach by conditional deletion of an essential autophagy mediator, Atg7. Deletion in adult mice in neurons of the SN was achieved by transduction of Atg7FL/FL mice with AAV Cre. Following ablation of Atg7, axons of the nigrostriatal projection were resistant to retrograde axon degeneration induced both by 6-OHDA and axotomy (Fig. 6) (Cheng et al., 2011). These observations, made in vivo, are in keeping with previous observations made in tissue culture suggesting that macroautophagy participates in axon destruction (Plowey et al., 2008, Yang et al., 2007).

Fig. 6.

Following deletion of Atg7, axons of SNpc dopamine neurons are resistant to retrograde axonal degeneration. (A) In the absence of AAV Cre injection, Atg7fl/fl:TH-GFP mice show a loss of MFB dopaminergic axons (visualized by confocal microscopy of endogenous GFP), and the appearance of axonal spheroid pathology (red arrows) following unilateral 6-OHDA injection (indicated by the red vertical bar to the right). Atg7wt/wt:TH-GFP mice injected with AAV Cre show a similar axon loss and pathology. However, following injection of AAV Cre, Atg7fl/fl:TH-GFP mice show minimal axon loss and pathology following 6-OHDA injection. (B) Following deletion of Atg7, nigro-striatal axons in Atg7fl/fl:TH-GFP mice show less pathology, and relatively preserved number, following anterior MFB axotomy, in comparison to Atg7wt/wt:TH-GFP mice. In the Atg7wt/wt:TH-GFP mice, numerous axon spheroids are observed (red arrows). (Images modified from (Cheng et al., 2011)).

Implications for treatment of PD

In recent years, there seems to be a growing pessimism among PD clinical researchers about our ability to ever develop treatments that will forestall the underlying neurodegeneration (Olanow et al., 2008). This pessimism is understandable given the recent failures of large clinical trials of promising lead compounds such as CEP-1347 in the PRECEPT trial. However, this pessimism may also stem in part from the widely held belief that at the onset of PD, 80% of striatal dopamine is depleted (Dauer and Przedborski, 2003, Kish et al., 1988, Marsden, 1990) and that 60% of SN dopamine neurons are lost (Dauer and Przedborski, 2003). This pervasive view is based on the work of Bernheimer et al (Bernheimer et al., 1973). However, as discussed previously, and as shown in Figure 2A, the original Bernheimer data do not stand up to this interpretation. More contemporary, comprehensive, and quantitative data clearly and consistently indicate that, at the onset of PD, there is, on average, only about a 30% loss of neurons. Data for striatal dopaminergic terminals indicate that a loss of about 50–60% is present at disease onset. Thus, there is an ample “window of opportunity” for protection of remaining neuronal elements.

This contemporary data also indicates that both at time of disease onset, and at its terminus, the degree of loss of striatal axons and terminals outweighs that of SN neuron loss. Therefore, throughout the course of the disease, it is the loss of axonal projections, not neuron cell bodies, that is limiting, and consequently it is the ongoing destruction of axons that is likely to be responsible for progressive clinical deterioration. This concept that ongoing degeneration of axons is the primary determinant of clinical progression is also in keeping with the neurobiology of this system, that it is impaired striatal terminal dopamine release that is responsible for the appearance of motor disabilities.

If it is loss of axons, not neuron cell bodes, that underlies clinical progression, then targeting the pathways of programmed cell death, which mediate destruction of cell bodies, not axons, may be mis-directed. Future attempts to design neuroprotective approaches may be more effective if they are targeted to the separate and distinct pathways of axon destruction. The “good news” is that there is every hope that the mechanisms of axon destruction will be identifiable and will offer many opportunities for therapeutic intervention. The ability of the WldS protein and Myr-Akt to achieve protection in models of nigro-striatal dopaminergic axon degeneration as we have described, offers just a first glimpse of the possibilities. The “bad news” is that we have a long way to go. We have only just begun to understand the molecular mechanism of WldS axon protection. The observation that Akt/Rheb/mTor signaling can regulate retrograde axon degeneration is the first example of a role for an endogenous cell signaling pathway. Much remains to be learned about the mechanisms involved and what other endogenous pathways may play a similar role.

Our proposal that axon degeneration, not neuron loss, plays the dominant role in causing the clinical manifestations of PD offers not only a new emphasis for the development of neuroprotective therapies, but also for neurorestoration. The prevailing focus on loss of neurons in PD has had a major impact on efforts to restore neural systems damaged by the disease. To date cell replacement therapies have been the focus of neurorestoration efforts. These efforts initially utilized fetal mesencephalic tissue, and more recently there is a surging interest in the use of human stem cells. Unfortunately, trials of fetal mesencephalic tissue were not successful; there was not much benefit, and some patients developed “runaway dyskinesias”, apparently due to the ectopic placement of dopamine-producing cells in the striatum (Freed et al., 2001, Ma et al., 2002). Depending on placement, pluripotent stem cell approaches may encounter similar difficulties. Stem cell approaches face other formidable hurdles: the potential for rejection (Zhao et al., 2011), tumorgenicity, poor survival, loss of phenotype and inability to achieve circuit integration.

Traditional views hold that once central nervous system axons are disrupted they are incapable of regeneration. Growing evidence, however, suggests that these views are not tenable in a variety of post-injury contexts. For example, enhanced Akt signaling has been shown to produce axon re-growth in models of both optic nerve (Park et al., 2008) and corticospinal tract injury (Liu et al., 2010). Moreover, we have shown for dopamine neurons that AAV transduction of SN with either Myr-Akt or hRheb 3 to 6 weeks after intra-striatal 6-OHDA lesion induces long-distance axon regrowth that achieves target re-contact and functional restoration (Kim et al., 2011). Thus, while replacement of lost neurons requires an exogenous implant, this is not the case for axons; endogenous, surviving neurons (of which there are 70% at disease onset) can be induced to re-grow their axons achieving correct anatomical organization and re-integration into surviving circuitry. Thus, a new focus on the neurobiology of axons offers better prospects for neurorestoration.

In sum, greater knowledge of the neurobiology of axons has a great deal to offer for our ability to understand the pathogenesis of PD and to treat it, both by prevention and by restoration. Given the mounting evidence that axonal impairment is the initiating lesion, re-directing therapeutic efforts towards maintaining connections versus saving the cell body seems of paramount importance. At the very least, efforts to delay axonal dysfunction may push back the disease clock allowing those afflicted to maintain an improved quality of life. Ultimately, therapeutics targeted towards both the axon and the cell body may provide the most efficacious treatment of all. We would predict that this knowledge would offer similar opportunities in addressing the challenges of other neurodegenerative diseases as well.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH NS26836 and NS38370, the Parkinson's Disease Foundation, and the Parkinson's Alliance (REB).

Abbreviations

- [3H]TBZOH

tritiated α-dihydrotetrabenazine

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AVs

autophagic vacuoles

- DLB

dementia with Lewy Bodies

- ILB

incidental Lewy bodies

- LB

Lewy body

- LRRK2

leucine rich repeat kinase 2

- MFB

medial forebrain bundle

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- SN

substantia nigra

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VMAT2

vesicular monoamine transporter

- WldS

Wallerian degeneration slow

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agid Y, Agid F, Ruberg M. Biochemistry of neurotransmitters in Parkinson's disease. In: Marsden CD, Fahn S, editors. Movement Disorders 2. Butterworths; London: 1987. pp. 166–230. [Google Scholar]

- Avery MA, Sheehan AE, Kerr KS, Wang J, Freeman MR. Wlds requires Nmnat1 enzymatic activity and N16-VCP interactions to suppress Wallerian degeneration. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:501–513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos SA, Martinez NW, Yoo S, Jara JS, Zamorano S, Hetz C, Twiss JL, Alvarez J, Court FA. Axonal degeneration is mediated by the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Neurosci. 2011;31:966–978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4065-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer H, Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, Jellinger K, Seitelberger F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J Neurol Sci. 1973;20:415–455. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(73)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, Schaap O, Breedveld GJ, Krieger E, Dekker MC, Squitieri F, Ibanez P, Joosse M. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Influence of strict, intermediate, and broad diagnostic criteria on the age-and sex-specific incidence of Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2000;15:819–825. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<819::aid-mds1009>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Sandmann-Keil D, Gai W, Braak E. Extensive axonal Lewy neurites in Parkinson's disease: a novel pathological feature revealed by alpha-synuclein immunocytochemistry. Neurosci Lett. 1999;265:67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueler H. Mitochondrial dynamics, cell death and the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Apoptosis. 2010;15:1336–1353. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE, Dauer WT, Vonsattel JP. A critical evaluation of the Braak staging scheme for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:485–491. doi: 10.1002/ana.21541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti G, Maggioni MG, Maci R. Influence of MPP+ on the state of tubulin polymerisation in NGF-differentiated PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:28–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<28::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti G, Surrey T, Maci R. The parkinsonism producing neurotoxin MPP+ affects microtubule dynamics by acting as a destabilising factor. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:4781–4786. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartelli D, Ronchi C, Maggioni MG, Rodighiero S, Giavini E, Cappelletti G. Microtubule dysfunction precedes transport impairment and mitochondria damage in MPP+ -induced neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2010;115:247–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Gertler TS, Surmeier DJ. A molecular basis for the increased vulnerability of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in aging and Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(Suppl 1):S63–S70. doi: 10.1002/mds.22801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rzhetskaya M, Kareva T, Bland R, During MJ, Tank AW, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. Antiapoptotic and trophic effects of dominant-negative forms of dual leucine zipper kinase in dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28:672–680. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2132-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HC, Burke RE. The Wld(S) mutation delays anterograde, but not retrograde, axonal degeneration of the dopaminergic nigro-striatal pathway in vivo. J Neurochem. 2010;113:683–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HC, Kim SR, Oo TF, Kareva T, Yarygina O, Rzhetskaya M, Wang C, During M, Talloczy Z, Tanaka K. Akt suppresses retrograde degeneration of dopaminergic axons by inhibition of macroautophagy. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2125–2135. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5519-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HC, Ulane CM, Burke RE. Clinical progression in Parkinson disease and the neurobiology of axons. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:715–725. doi: 10.1002/ana.21995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Kruse SE, Palmiter RD, Xia Z. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition is not required for dopaminergic neuron death induced by rotenone, MPP+, or paraquat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15136–15141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807581105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Palmiter RD, Xia Z. Loss of mitochondrial complex I activity potentiates dopamine neuron death induced by microtubule dysfunction in a Parkinson's disease model. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:873–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MP, Freeman MR. Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmnat. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:245–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MP, Perry VH. Axon pathology in neurological disease: a neglected therapeutic target. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti L, Wilbrey A, Morreale G, Janeckova L, Beirowski B, Adalbert R, Mazzola F, Di Stefano M, Hartley R, Babetto E. Wld S protein requires Nmnat activity and a short N-terminal sequence to protect axons in mice. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:491–500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver JA, Logroscino G, Gaziano JM, Kurth T. Incidence and remaining lifetime risk of Parkinson disease in advanced age. Neurology. 2009;72:432–438. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341769.50075.bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda JE, Giasson BI, Mabon ME, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:205–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt O, Coelln RV, Kugler S, Lindenau J, Rathke-Hartlieb S, Gerhardt E, Haid S, Isenmann S, Gravel C, Srinivasan A, et al. Protection by synergistic effects of adenovirus-mediated X-chromosome-linked inhibitor of apoptosis and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor gene transfer in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9126–9134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09126.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O. Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system. Klin Wochenschr. 1960;38:1236–1239. doi: 10.1007/BF01485901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khodor BF, Burke RE. Medial forebrain bundle axotomy during development induces apoptosis in dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra and activation of caspases in their degenerating axons. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2002;452:65–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S. Does levodopa slow or hasten the rate of progression of Parkinson's disease? J Neurol. 2005;252(Suppl 4):IV37–IV42. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-4008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer M, Kachergus J, Forno L, Lincoln S, Wang DS, Hulihan M, Maraganore D, Gwinn-Hardy K, Wszolek Z, Dickson D. Comparison of kindreds with parkinsonism and alpha-synuclein genomic multiplications. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:174–179. doi: 10.1002/ana.10846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114:2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Yan T, He Z, Zhai Q. Wld(S), Nmnats and axon degeneration--progress in the past two decades. Protein Cell. 2010;1:237–245. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn JT, Weil M, Archer F, Siman R, Srinivasan A, Raff MC. Evidence that Wallerian degeneration and localized axon degeneration induced by local neurotrophin deprivation do not involve caspases. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1333–1341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KG, Fingar DC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14071–14077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.094003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed CR, Greene PE, Breeze RE, Tsai WY, DuMouchel W, Kao R, Dillon S, Winfield H, Culver S, Trojanowski JQ. Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson's disease. New Eng J Med. 2001;344:710–719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuente-Fernandez R, Schulzer M, Kuramoto L, Cragg J, Ramachandiran N, Au WL, Mak E, McKenzie J, McCormick S, Sossi V, et al. Age-specific progression of nigrostriatal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:803–810. doi: 10.1002/ana.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE, Uryu K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Axon pathology in Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia hippocampus contains alpha-, beta-, and gamma-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13450–13455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reitbock P, Anichtchik O, Bellucci A, Iovino M, Ballini C, Fineberg E, Ghetti B, Della Corte L, Spano P, Tofaris GK, et al. SNARE protein redistribution and synaptic failure in a transgenic mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2010;133:2032–2044. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greffard S, Verny M, Bonnet AM, Beinis JY, Gallinari C, Meaume S, Piette F, Hauw JJ, Duyckaerts C. Motor score of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale as a good predictor of Lewy body-associated neuronal loss in the substantia nigra. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:584–588. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Cookson MR. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 mutations and Parkinson's disease: three questions. ASN Neuro. 2009;1 doi: 10.1042/AN20090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasbani DM, O'Malley KL. Wld(S) mice are protected against the Parkinsonian mimetic MPTP. Exp Neurol. 2006;202:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasbani DM, Perez FA, Palmiter RD, O'Malley KL. Dopamine depletion does not protect against acute 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine toxicity in vivo. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9428–9433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0130-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings TG. The role of dopamine oxidation in mitochondrial dysfunction: implications for Parkinson's disease. J.Bioenerg.Biomembr. 2009;41:469–472. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayley S, Crocker SJ, Smith PD, Shree T, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Mount M, Slack R, Anisman H, Park DS. Regulation of dopaminergic loss by Fas in a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2045–2053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Little MD, Bankiewicz K, Yang SC, Markey SP, Johannessen JN. Selective retention of MPP+ within the monoaminergic systems of the primate brain following MPTP administration: an in vivo autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1991;40:133–158. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90180-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornykiewicz O. Biochemical aspects of Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1998;51:S2–S9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2_suppl_2.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Manning BD. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST0370217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami K, Koike T. Non-apoptotic neurite degeneration in apoptotic neuronal death: pivotal role of mitochondrial function in neurites. Neuroscience. 2003;122:617–626. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseki E, Kato M, Marui W, Ueda K, Kosaka K. A neuropathological study of the disturbance of the nigro-amygdaloid connections in brains from patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Sci. 2001;185:129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai A, Masliah E, Yoshimoto M, Ge N, Flanagan L, de Silva HAR, Kittel A, Saitoh T. The precursor protein of non-Aá component of Alzheimer's disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron. 1995;14:467–475. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel M, Nichols RJ, Deak M, Campbell DG, Gillardon F, Knebel A, Alessi DR. LRRK2 phosphorylates moesin at threonine-558: characterization of how Parkinson's disease mutants affect kinase activity. Biochem.J. 2007;405:307–317. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Letters. 2010;584:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Han JS, Antenor-Dorsey JA, O'Malley KL. The Parkinsonian mimetic, MPP+, specifically impairs mitochondrial transport in dopamine axons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7212–7221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0711-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Chen X, Oo TF, Kareva T, Yarygina O, Wang C, During MJ, Kholodilov N, Burke RE. Dopaminergic pathway reconstruction by Akt/Rheb-induced axon regeneration. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:110–120. doi: 10.1002/ana.22383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. New Eng J Med. 1988;318:876–880. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer ML, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ. Presynaptic alpha-synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1405–1410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger R, Kuhn W, Muller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kosel S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Schols L, Riess O. Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease [letter] Nat Genet. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupsky WJ, Grimes MM, Sweeting J, Bertsch R, Cote LJ. Parkinson's disease and megacolon: concentric hyaline inclusions (Lewy bodies) in enteric ganglion cells. Neurology. 1987;37:1253–1255. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–3594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KE, Fon EA, Hastings TG, Edwards RH, Sulzer D. Methamphetamine-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons involves autophagy and upregulation of dopamine synthesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8951–8960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08951.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Samii A, Sossi V, Ruth TJ, Schulzer M, Holden JE, Wudel J, Pal PK, Fuente-Fernandez R, Calne DB. In vivo positron emission tomographic evidence for compensatory changes in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:493–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2009;373:2055–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60492-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LH, Qin HZ, Wang JL, Wang J, Wang XL, Gao GD. Axonal degeneration of nigra-striatum dopaminergic neurons induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in mice. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:455–463. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu W, Oo TF, Wang L, Tang Y, Jackson-Lewis V, Zhou C, Geghman K, Bogdanov M, Przedborski S, et al. Mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:826–828. doi: 10.1038/nn.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang CL, Wang TT, Luby-Phelps K, German DC. Mitochondria mass is low in mouse substantia nigra dopamine neurons: implications for Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Lu Y, Lee JK, Samara R, Willenberg R, Sears-Kraxberger I, Tedeschi A, Park KK, Jin D, Cai B, et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1075–1081. doi: 10.1038/nn.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotharius J, O'Malley KL. The parkinsonism-inducing drug 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium triggers intracellular dopamine oxidation. A novel mechanism of toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38581–38588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn ER, Perry VH, Brown MC, Rosen H, Gordon S. Absence of Wallerian Degeneration does not Hinder Regeneration in Peripheral Nerve. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1:27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SY, Roytta M, Rinne JO, Collan Y, Rinne UK. Correlation between neuromorphometry in the substantia nigra and clinical features in Parkinson's disease using disector counts. J Neurol Sci. 1997;151:83–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Feigin A, Dhawan V, Fukuda M, Shi Q, Greene P, Breeze R, Fahn S, Freed C, Eidelberg D. Dyskinesia after fetal cell transplantation for parkinsonism: a PET study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:628–634. doi: 10.1002/ana.10359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack TG, Reiner M, Beirowski B, Mi W, Emanuelli M, Wagner D, Thomson D, Gillingwater T, Court F, Conforti L, et al. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/nn770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D, Dowman J, Hammond R, Leete T, Inoue K, Abeliovich A. The familial Parkinsonism gene LRRK2 regulates neurite process morphology. Neuron. 2006;52:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marella M, Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Greenamyre JT, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Protection by the NDI1 gene against neurodegeneration in a rotenone rat model of Parkinson's disease. PLoS.One. 2008;3:e1433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: A neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2804–2815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02804.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CD. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 1990;335:948–952. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91006-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda W, Furuta T, Nakamura KC, Hioki H, Fujiyama F, Arai R, Kaneko T. Single nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons form widely spread and highly dense axonal arborizations in the neostriatum. J Neurosci. 2009;29:444–453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4029-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner W, Prunier C, Guilloteau D, Chalon S, Gross CE, Bezard E. Time-course of nigrostriatal degeneration in a progressive MPTP-lesioned macaque model of Parkinson's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;28:209–218. doi: 10.1385/MN:28:3:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijatovic J, Piltonen M, Alberton P, Mannisto PT, Saarma M, Piepponen TP. Constitutive Ret signaling is protective for dopaminergic cell bodies but not for axonal terminals. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1486–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfini G, Pigino G, Opalach K, Serulle Y, Moreira JE, Sugimori M, Llinas RR, Brady ST. 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium affects fast axonal transport by activation of caspase and protein kinase C. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2007;104:2442–2447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611231104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroyama A, Kobayashi S, Mitsumoto Y. Loss of striatal dopaminergic terminals during the early stage in response to MPTP injection in C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci Res. 2011;69:352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandhagopal R, McKeown MJ, Stoessl AJ. Functional imaging in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1478–1488. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310432.92489.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev A, McLaughlin T, O'Leary DD, Tessier-Lavigne M. APP binds DR6 to trigger axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases. Nature. 2009;457:981–989. doi: 10.1038/nature07767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Schapira AH. Why have we failed to achieve neuroprotection in Parkinson's disease? Ann Neurol. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S101–S110. doi: 10.1002/ana.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orimo S, Uchihara T, Nakamura A, Mori F, Kakita A, Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H. Axonal alpha-synuclein aggregates herald centripetal degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131:642–650. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglini G, Kunda P, Quiroga S, Kosik K, Caceres A. Suppression of radixin and moesin alters growth cone morphology, motility, and process formation in primary cultured neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:443–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]