Abstract

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand activated transcription factor. Activation of AHR mediates the expression of target genes (e.g. CYP1A1), by binding to dioxin response element (DRE) sequences in their promoter region. To understand the multiple mechanisms of AHR-mediated gene regulation, a microarray analysis on liver isolated from ligand-treated transgenic mice expressing a wild-type Ahr or a DRE-binding mutant Ahr (A78D) on an ahr-null background was performed. Results revealed that AHR DRE-binding is not required for suppression of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis. Quantitative RT- PCR performed on both mouse liver and primary human hepatocyte RNA demonstrated a coordinate repression of genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis, namely HMGCR, FDFT1, SQLE and LSS following receptor activation. An additional transgenic mouse line was established expressing a liver-specific Ahr-A78D on a CreAlb/Ahrflox/flox background. These mice displayed a similar repression of cholesterol biosynthetic genes compared to Ahrflox/flox mice, further indicating that the observed modulation is AHR-specific and occurs in a DRE-independent manner. Elevated hepatic transcriptional levels of the genes of interest were noted in congenic C57BL/6J-Ahd allele mice, when compared to the WT C57BL/6J mice, which carry the Ahb allele. Down-regulation of ARNT levels using siRNA in a human cell line revealed no effect on the expression of cholesterol biosynthetic genes. Finally, cholesterol secretion was shown to be significantly decreased in human cells following AHR activation.

Conclusion

These data firmly establish an endogenous role for AHR as a regulator of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway independent of its DRE-binding ability and suggest that AHR may be a previously unrecognized therapeutic target.

Keywords: AHR, aryl hydrocarbon, cholesterol synthesis, DRE, HMGCR

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand activated transcription factor belonging to the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) – Per ARNT Sim (PAS) family of transcription factors. Ligands for the AHR include the planar, hydrophobic halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), many of which are environmental contaminants. Activation of AHR by xenobiotic agonists such as TCDD (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin), a prototypic potent ligand, is known to have toxic consequences, illustrating its role as an exogenous chemical sensor. Atypical ligands include bilirubin and indirubin 1, 2. The presence of potent endogenous ligands for the human AHR exhibiting agonistic activities such as kynurenic acid 3 and 3-indoxyl sulfate 4 have been identified.

Upon ligand binding, the AHR heterodimerizes with the AHR nuclear translocator protein (ARNT), another bHLH-PAS family member 5. The AHR/ARNT heterodimer represents a fully competent transcription factor capable of binding a consensus sequence known as dioxin or xenobiotic response element (DRE or XRE). This specific high affinity interaction stimulates transcription of xenobiotic target genes, including cytochrome P450s CYP1A1 and CYP1B1, which are involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics. Interestingly, the regulation of xenobiotic metabolism in tissues (e.g. intestinal tract) by the AHR is important in the clearance of endogenous and exogenous compounds 6. Ahr-null mice exhibit a defined set of physiological phenotypes comprising a reduction in peripheral lymphocytes, vascular abnormalities in the heart and liver, diminished fertility, and overall slower growth, all of which indicate a constitutive role for the receptor 5. A growing list of AHR target genes has been identified that clearly point to a physiological role for the AHR beyond regulating xenobiotic metabolism. AHR target genes that play a role in cell proliferation, cell cycle control, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inflammation (e.g., slug, epiregulin) have been identified 7, 8.

Microarray studies performed in mice have revealed that daily exposure to low levels of TCDD had a profound impact on the expression of genes involved in circadian rhythm, cholesterol biosynthesis, fatty acid synthesis, and glucose metabolism in the liver 9. A similar study performed in rats revealed that high levels of TCDD exposure were required to alter genes involved in cholesterol metabolism and bile acid synthesis and transport 10. This observation is also supported by a study indicating a disruption in lipid metabolism in male guinea pigs through changes in expression of cholesterol synthesis genes following TCDD treatment 11. These results are consistent with TCDD-induced anorexia and wasting syndrome characterized by weight loss, muscle atrophy and a loss of appetite observed in rats 12. Results from human exposure studies revealed a significant disruption in lipid metabolism and high cholesterol and triglyceride levels in blood of workers exposed to TCDD 13. Taken together, these results strongly suggest the involvement of AHR in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis in rodents and humans.

The essential roles for cholesterol and the human diseases caused by disorders in its metabolism prompted the study of its mode of regulation in order to control its levels in vivo 14. In the body, cholesterol is either derived from the diet or from de novo synthesis occurring mainly in the liver through the mevalonate pathway. This pathway comprises several enzymes such as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase (FDFT1), squalene epoxidase (SE) and oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC), all of which have been shown to be under the regulation of the transcription factor sterol element binding protein 2 (SREBP2) 15.

Nuclear receptors such as the estrogen receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor have been shown to function through alternate mechanisms in the absence of DNA-binding. Our laboratory has already established that DRE-binding was not necessary for ligand activated AHR to directly attenuate acute-phase gene expression, namely Saa3 16. This result has led us to test the hypothesis that the AHR can regulate gene expression in the absence of DRE binding in the liver. Using a transgenic mouse model that expresses the DRE-binding mutant AHR-A78D and microarray analysis, we examined the genes that are altered by activation of this receptor. Upon injection with β-naphthoflavone (BNF), an AHR agonist, the major class of genes markedly repressed was directly involved in cholesterol metabolism. We found a similar change in primary human hepatocytes following receptor activation, demonstrating receptor involvement in regulating cholesterol synthesis both in vivo in mice, and in human cells. Absence of the AHR in mice and human cells correlated with an increased level of expression of those enzymes, further proving an endogenous role of the receptor in cholesterol homeostasis in the absence of any exogenous ligand. Finally, we demonstrated that repression of cholesterol synthesis gene expression was mirrored by a repression in the rate of cholesterol secretion in primary human hepatocytes.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

Hep3B cells, a human hepatoma-derived cell line, were maintained in α-minimal essential medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Labs, Logan, UT), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma) in a humidified incubator at 37°C, with an atmospheric composition of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Primary human hepatocytes

Primary human hepatocytes were obtained from the University of Pittsburgh, through the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System, NIH Contract #N01-DK-7-0004 /HHSN267200700004C. Cells were kindly provided by Curt Omiecinski and Stephen Strom. Culture details have been reported previously 17. 48 h following Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) addition, cells were exposed to BNF (10µM) or carrier solution for 5 h.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

RNA samples were isolated from cell cultures and mouse livers using TRI Reagent according to the manufacturer’s specifications (Sigma Aldrich). cDNA was generated using the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Quantitative PCR

Sequences of primers (Suppl. Table 1) were designed to detect mRNA levels. PerfeCTa™ SYBR® Green SuperMix for iQ (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) was used and analysis was conducted using MyIQ software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Gene silencing

AHR and ARNT levels were decreased in Hep3B cells using siRNA as previously described 18. 72 h post-electroporation, RNA and protein samples were isolated.

Mice

The cDNA for the mouse A78D-Ahr or the wild-type Ahr were inserted into the pTTR1 EXV3 vector (obtained from Dr. Terry Van Dyke, University of North Carolina), which mediates hepatocyte specific expression through the Ttr promoter. A78D-AhrTtr and AhrTtr fragments were then microinjected into C57BL/6J fertilized eggs at the Penn State University Transgenic Mouse Facility. Transgenic mice A78D-AhrTtr and AhrTtr were mated with Ahr(−/−) and the albumin promoter-driven, Cre recombinase-expressing CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice (a kind gift from Christopher Bradfield, University of Wisconsin) to produce transgenic A78D-AhrTtr-Ahr(−/−), AhrTtr Ahr(−/−), A78D-AhrTtr CreAlbAhrflox/flox and AhrTtr CreAlbAhrflox/flox. Congenic Ahd and wild-type mice (C57BL/6J) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were genotyped using relevant primers as described previously 19. Mice were housed on corncob bedding in a temperature- and light-controlled facility and given access to food and water ad libitum. Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free facility and treated with humane care with approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pennsylvania State University. Adult (10–12 weeks) female mice of different genotypes were injected intraperitoneally with BNF at 50 mg/kg dissolved in corn oil or with corn oil alone for 5 h. Mice were sacrificed via CO2 inhalation.

DNA microarray: isolation of RNA and data analysis

Livers were isolated from mice injected with BNF (50 mg/kg) or corn oil for 5 h. DNA microarray analysis of those samples was performed as described previously 20.

Protein and RNA Preparation

Mouse liver samples were collected and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80°C, RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent (Sigma). Livers were homogenized in MENG buffer (25 mM MOPS, 2 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3, and 10% glycerol, pH 7.5) with protease inhibitors (Sigma) using a Dounce homogenizer. Hep3B extracts were prepared in MENG buffer, 1% NP-40 and proteinase inhibitors. Cell homogenates were then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes and proteins were analyzed.

Immunoblotting

Mouse liver and cell extracts were resolved on 8% SDS-tricine polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane and detected using the mouse AHR monoclonal antibody RPT1 (Thermo Scientific). All other primary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1/1000 dilution) and were visualized using a secondary biotinylated antibody and [I125]streptavidin followed by autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test in GraphPad Prism (v.5.01) software to determine statistical significance between treatments. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P<0.05; **P<0.01;***P<0.001).

Results

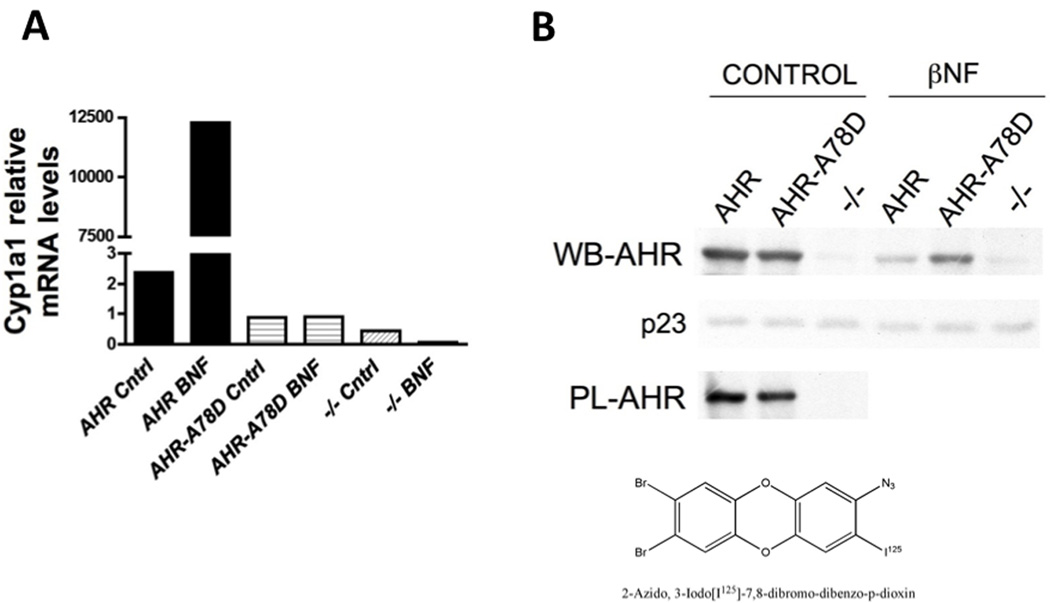

Characterization of a Transgenic Mouse Lines Expressing a DRE-Binding Mutant or WT AHR

Our laboratory has previously established that A78D modification in the mouse AHR is sufficient to render the receptor unable to bind DRE sequences without compromising its other functions 21. In the current study, we wanted to further address the ability of the AHR to affect hepatic gene expression in vivo independent of its DRE binding activity. For this purpose, we cloned the wild-type (WT) Ahr and the A78D-Ahr vector under the regulation of the hepatocyte-specific transtherytin (TTR) promoter. We established the AhrTtr and A78D-AhrTtr expression vectors in mice, which were then backcrossed onto an ahr-null background. The resulting mice were ahr-null with either the WT or the DRE-binding mutant form of the receptor expressed exclusively in the hepatocytes. Fig. 1A confirms that the A78D modification completely abolishes BNF-dependent induction of DRE-driven Cyp1a1 activity. To ensure that the expression of the transgene was intact, liver proteins were subjected to western blot analysis and the results revealed a similar level of expression. Finally, a photo-affinity ligand experiment demonstrated that the ligand-binding ability of the receptor was not affected by the mutation (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of Ahr transgenic mouse lines. (A) BNF-dependent activation of Cyp1a1, a DRE-driven gene, is completely abolished in A78D-AhrTtr Ahr(−/−) (AHR-A78D) transgenic mice to levels similar to Ahr (−/−). (B) Liver protein expression of transgenic mice confirms a similar expression of the A78D-AhrTtrAhr(−/−) and the AhrTtrAhr(−/−) (AHR) proteins in control and BNF-treated mice. Ligand binding shows the ability of the mutant receptor to bind a photoaffinity ligand (PL-AHR). The structure of the photoaffinity ligand is shown.

DNA Microarray Analysis

Transcript profiling was performed on liver RNA isolated from mice of each genotype: ahr-null and our transgenic mouse lines AhrTtrAhr(−/−) and A78D-AhrTtr - Ahr(−/−). Subsequent data analysis pointed to a suppression of a large subset of genes involved in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway when AHR was activated regardless of its ability to bind the consensus DRE sequence (Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. 1). Conversely, no change in the transcript levels of those genes was noted when ahr-null mice were similarly treated, further indicating that the observed change in gene expression in the AhrTtr and A78D-AhrTtr transgenic mice was AHR-mediated.

Table 1.

Liver gene expression of transgenic A78D-AhrTtrAhr(−/−) or AhrTtrAhr(−/−) treated with BNFa.

| Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Ratio WT +/− BNF | Ratio A78D +/− BNF | Ratio Ahr (−/−) +/− BNF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *** Cytochrome P450, family 51 | Cyp51 | −1.4 | −1.4 | −0.1 |

| Down syndrome critical region gene 1-like 1 | Dscr1l1 | −1.4 | −0.6 | 0.2 |

| *** 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A synthase 1 | Hmgcs1 | −1.3 | −1.4 | 0.2 |

| *** Lanosterol synthase | Lss | −1.3 | −0.8 | −0 |

| *** 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase | Hmgcr | −1.2 | −0.6 | 0.4 |

| *** Farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1 | Fdft1 | −1.2 | −1.2 | 0 |

| *** Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase | Idi1 | −1.1 | −1.4 | −0.1 |

| Coenzyme Q10 homolog B (S. cerevisiae) | Cog10b | −1.1 | −0.4 | 0 |

| NAD(P) dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like | Nsdhl | −1.1 | −0.6 | 0.1 |

| *** Sterol-C4-methyl oxidase-like | Sc4mol | −1 | −1.2 | −0.2 |

| *** Acetyl-Coenzyme A acetyltransferase 2 | Acat2 | −1 | −0.4 | 0.2 |

| Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 | Pcsk9 | −1 | −0.9 | 0.2 |

| *** Hydroxysteriod (17-beta) dehydrogenase 7 | Hsd17b7 | −1 | −0.7 | 0.3 |

| Retinol dehydrogenase 11 | Rdh11 | −0.9 | −0.8 | 0.2 |

| *** Phosphomevalonate kinase | Pmvk | −0.8 | −0.8 | 0.4 |

| Retinol dehydrogenase | Rdh11 | −0.8 | −0.6 | 0.1 |

| Macrophage activation 2 like | Mpa2l | −0.8 | −0.5 | −0.2 |

| *** 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase | Dhcr7 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.3 |

| *** Squalene epoxidase | Sqle | −0.6 | −1.2 | 0 |

| *** Mevalonate (diphospho) decarboxylase | Mvd | −0.6 | −0.4 | 0 |

| UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase | Ugcg | −0.6 | −0.4 | −0.1 |

| Latrophilin 2 | Lphn2 | −0.6 | −0.5 | −0.2 |

| Carboxylesterase 5 | Ces5 | −0.6 | −0.4 | 0.1 |

| Camello-like 2 | Cml2 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −0.1 |

| Cytochrome b5 type B | Cyb5b | −0.5 | −0.6 | 0 |

| Cytochrome b5 type B | Cyb5b | −0.4 | −0.6 | −0 |

| Antiproteinase, antritrypsin, member 7 | Serpina7 | −0.4 | −0.6 | −0.1 |

| Hydroxyacyl glutathione hydrolase | Hagh | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.1 |

| Carboxylesterase 3 | Ces3 | −0.4 | −0.9 | −0.2 |

| Immunity-related GTPase family, M | Irgm | −0.4 | −0.4 | 0.1 |

| Dimethylglycine dehydrogenase precursor | Dmgdh | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.1 |

Results indicate ratio of BNF- compared to vehicle-treated mice.

Genes that are directly part of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway are indicated (***).

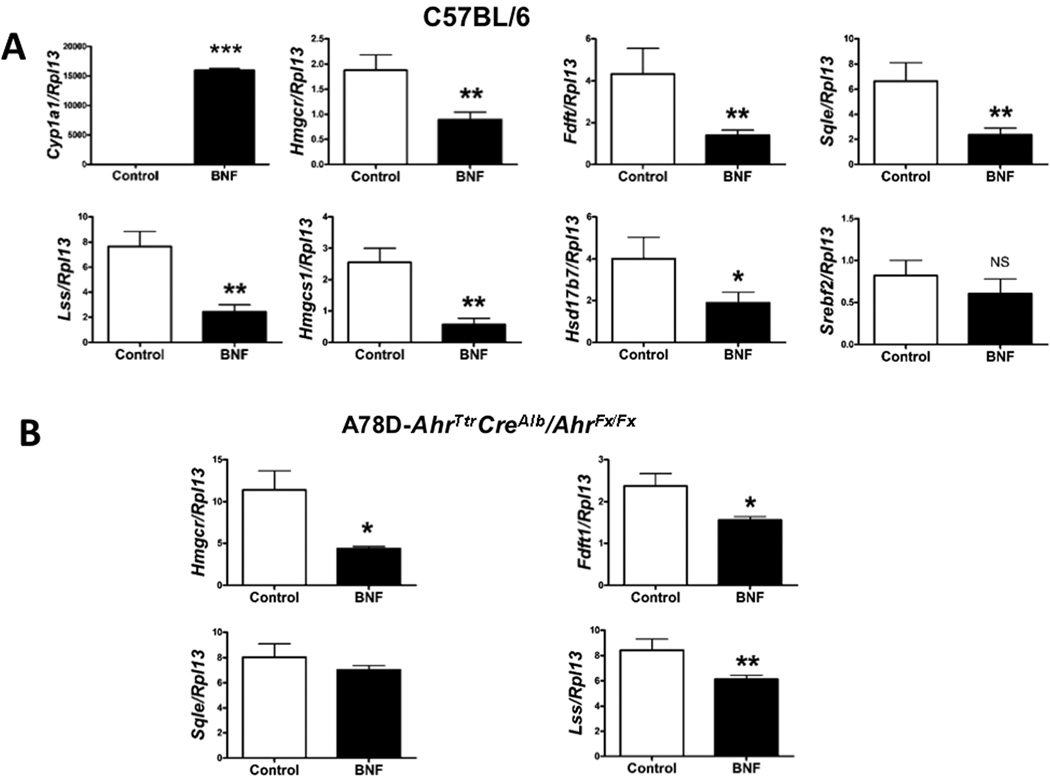

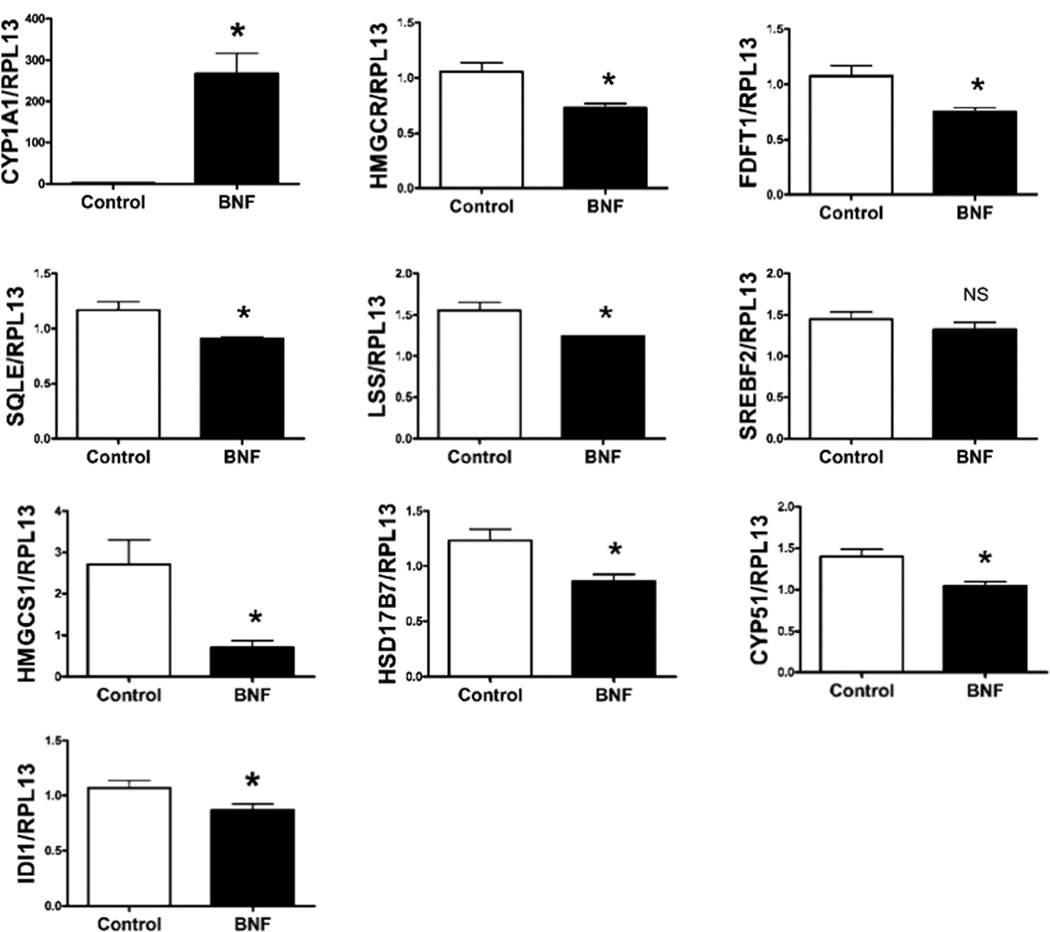

Regulation of Cholesterol Synthesis Gene Expression by AHR in vivo

In order to validate our microarray data, we injected WT mice with BNF. Cyp1a1 levels were utilized as a positive control for receptor activation (Fig. 2A). Hepatic RNA levels of selected cholesterol synthesis genes, including the gene encoding the pivotal rate-limiting enzyme of the cholesterol synthesis pathway HMGCR, were revealed to be significantly repressed when BNF was administered. Interestingly, SREBF2 expression showed no significant change. From this point on, we decided to focus on the genes encoding the most studied and critical enzymes in the mevalonate pathway: hmgcr, fdft1, sqle, and lss. These enzymes have been the subject of extensive studies to find a new therapeutic target in order to down-regulate the activity of the cholesterol synthesis pathway 22.

Fig. 2.

Repression of cholesterol synthesis gene expression following wild-type and DRE-binding mutant AHR activation in mice. (A) Normalized hepatic RNA expression of cholesterol metabolism genes in wild-type mice (6 female mice per group) injected with BNF versus control mice are shown. (B) Normalized hepatic mRNA levels from A78D-AhrTtr CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice injected with BNF compared to vehicle-treated mice (6 female mice per group). (Fig 2A and 2B are different experiments).

Regulation of Cholesterol Synthesis Gene Expression by AHR in a DRE-independent manner

Due to the compromised physiological condition of ahr-null mice, we decided to establish the A78D-AhrTtr transgene on a CreAlbAhrflox/flox background. The resulting mice expressed the Ahrflox/flox receptor in all tissues except in hepatocytes, where the A78D-AhrTtr transgene was present and failed to induce Cyp1a1 (Suppl. Fig. 2). This mutation did not affect the basal level of expression of our genes of interest (Suppl. Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 2B, a similar repression in the expression of hepatic cholesterol synthesis genes occurs in the A78D-AhrTtr CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice when the receptor was activated. The levels of these transcripts in the liver exhibited no difference upon BNF treatment of CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice, further confirming that the BNF effect in WT and transgenic DRE-binding mutant mice was mediated through AHR (Suppl. Fig. 4).

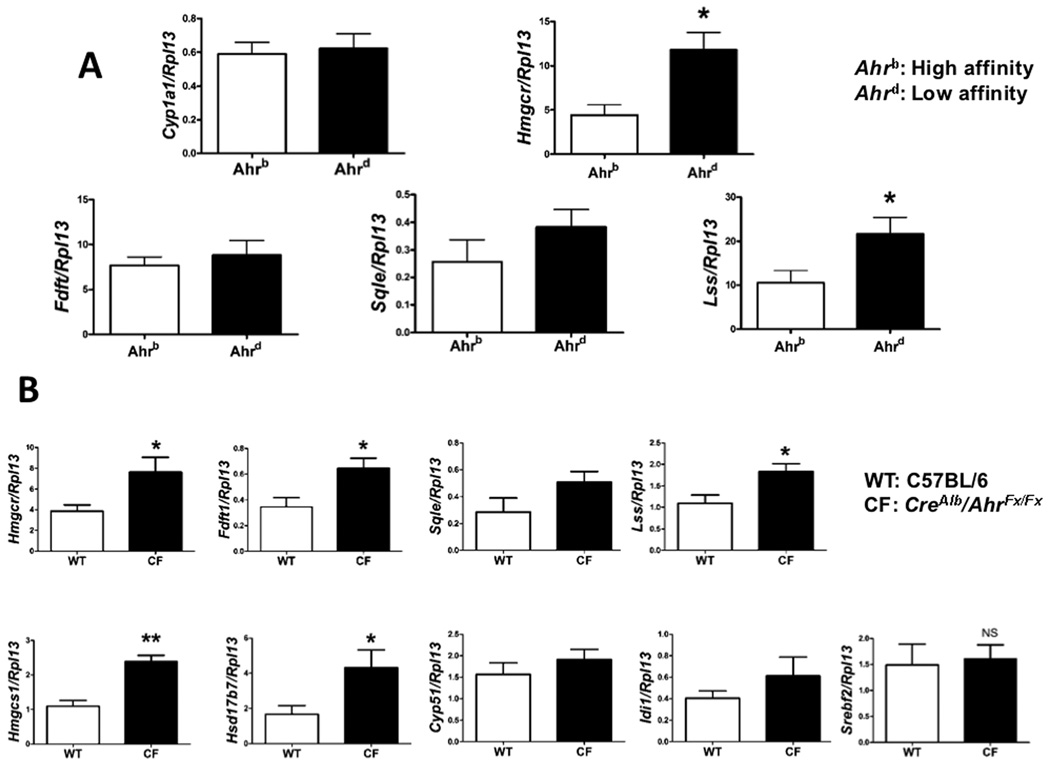

Constitutive Role for AHR in the Regulation of Cholesterol Synthesis Gene Expression

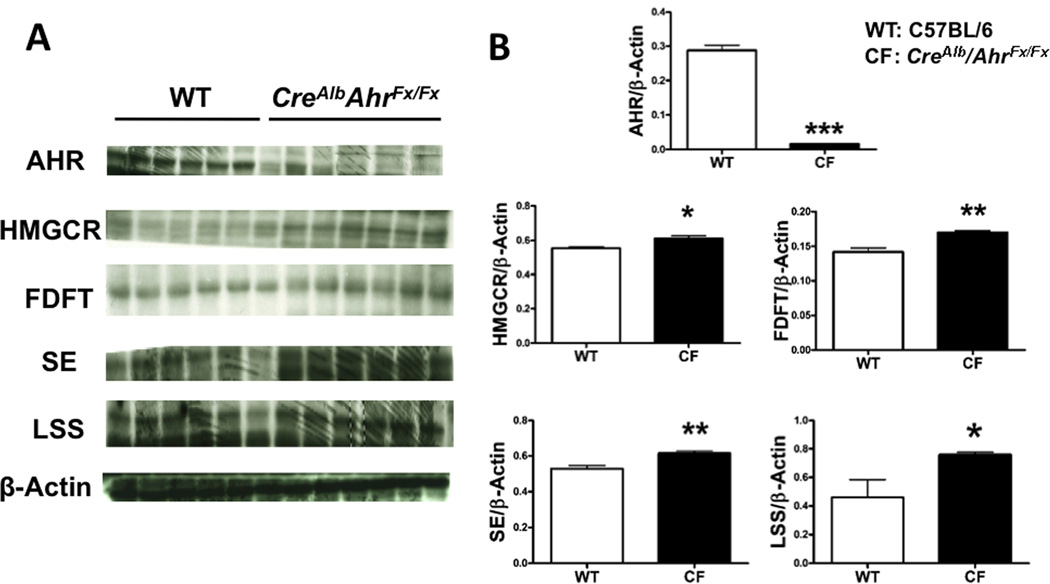

We tested whether there is a difference in constitutive expression of genes in the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway between Ahd allele (low ligand affinity) on a C57BL6/J background and Ahb allele (high affinity) in C57BL6/J mice. These two allelic forms of the AHR differ in their ability to mediate induction of AHR activity upon ligand treatment. Higher transcriptional levels of cholesterol synthesis genes were noted in Ahd congenic mice compared to C57BL/6 mice, suggesting a role for endogenous AHR ligands in modulating the expression of cholesterol synthesis genes (Fig. 3A). In contrast to the extensive repressive activity observed in C57BL/6 mice, no significant differences were noted in the BNF-treated in Ahd congenic mice compared to control (Supplementary Fig. 5). This supports the notion that receptor activation by a ligand mediates suppression of cholesterol synthesis gene expression. Next, whether the presence of the AHR constitutively attenuates the expression of cholesterol synthesis genes was examined. To directly test this hypothesis, we assessed the constitutive hepatic levels of hmgcr, fdft1, sqle and lss between CreAlbAhrflox/flox and C57BL/6 mice. Results revealed that an absence of the receptor correlated with a significant elevated level of gene expression and corresponding protein levels of these enzymes (Fig. 3B and 4).

Fig. 3.

AHR unresponsive allele and AHR absence correlated with a higher expression of cholesterol synthesis genes. (A) Normalized hepatic mRNA of cholesterol biosynthetic genes in Ahb and Ahd congenic mice (6 female mice per group) are shown in the absence of any exogenous ligand. (B) Normalized mRNA hepatic expressions of selected cholesterol biosynthetic genes in CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice (CF) are compared to C57BL/6J (WT) mice (6 female mice per group) in the absence of exogenous ligand.

Fig. 4.

AHR absence in mice correlated with a higher protein expression of cholesterol synthesis genes. (A) Hepatic protein expressions of cholesterol biosynthetic genes in liver-specific CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice (CF) are compared to C57BL/6J (WT) mice (6 female mice per group) in the absence of exogenous ligand. (B) Quantification of protein expression normalized to β-actin.

Role for AHR in the Regulation of the Genes in the Cholesterol Synthetic Pathway in Primary Human Cells

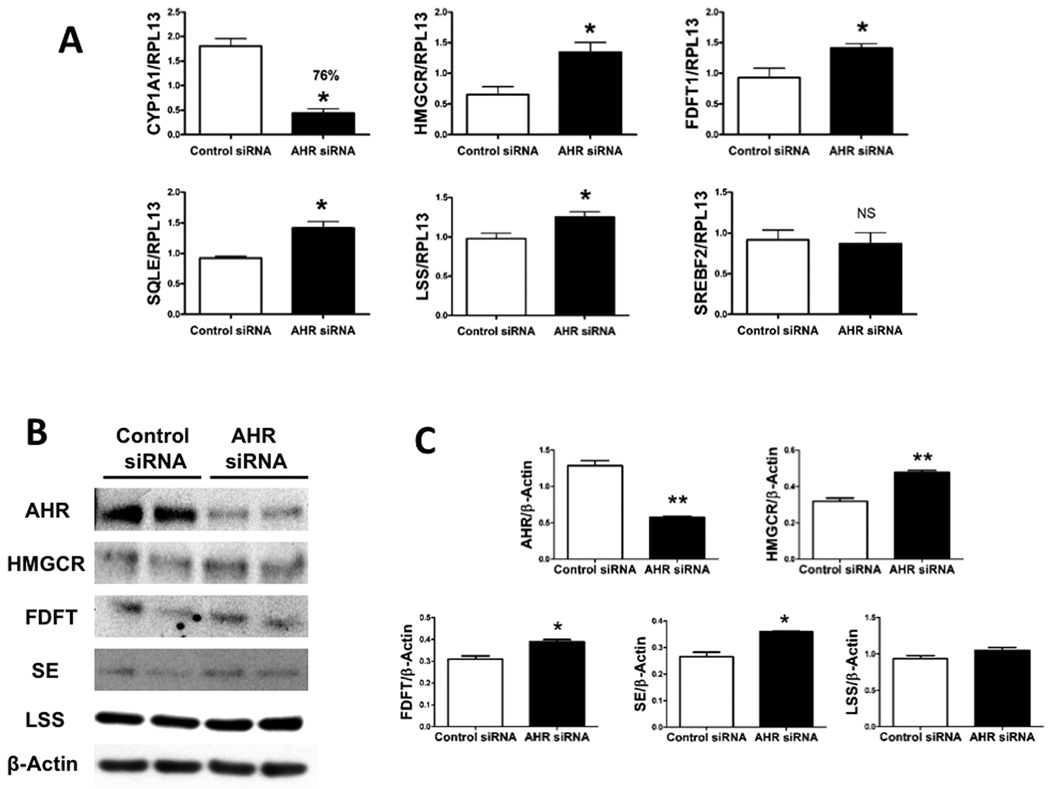

Primary human hepatocytes were administered BNF and subsequent analysis of mRNA levels revealed a significant decrease in the four core de novo cholesterol biosynthesis genes (Fig. 5). We also examined other enzymes in the pathway, CYP51, HMGCS1, HSD17B7, and IDI1; they showed a similar trend of repression further suggesting a general regulation of the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway by AHR (Fig. 5). However, SREBP2 expression levels were not altered by BNF treatment. In order to further explore the mechanism of this regulation, AHR siRNA was used to decrease expression of the AHR in human Hep3B cells. Similar to our in vivo results in mice, enhanced expression of the mRNA and protein levels of the genes of interest correlated with lower AHR levels (Fig. 6). Consistent with our mouse data, this establishes a role for AHR in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis in humans.

Fig. 5.

Repression of cholesterol synthesis gene expression following AHR activation in primary human hepatocytes. Normalized mRNA expression of selected cholesterol biosynthesis genes of primary human hepatocytes (3 wells per group) are shown.

Fig. 6.

Lower levels of AHR in human cells correlated with higher cholesterol synthesis gene expression. (A) Normalized RNA hepatic expression of selected cholesterol biosynthesis genes in Hep3B cells where AHR has been down-regulated (AHR siRNA) are compared to control cells in the absence of exogenous ligand. CYP1A1 levels are used to confirm down-regulation of the receptor. (B) Hepatic protein expression of selected cholesterol biosynthetic genes in AHR down-regulated Hep3B cells (AHR siRNA) are compared to control cells in the absence of exogenous ligand. (C) Quantification of protein expression is normalized to β-actin.

ARNT has been linked to cholesterol homeostasis through its regulation of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1), a major reverse cholesterol transporter 23. Agonist treatment leads to the formation of AHR-ARNT heterodimer formation, the ablation of ARNT expression can assess whether this heterodimer plays a role in gene repression studied here. Unlike AHR, partial absence of ARNT in Hep3B cells had no effect on the mRNA levels of cholesterol synthesis genes, suggesting that the AHR mediates gene repression in the absence of heterodimer formation (Suppl. Fig. 6). This result is consistent with the ability of the DRE-binding mutant AHR to repress the genes described here.

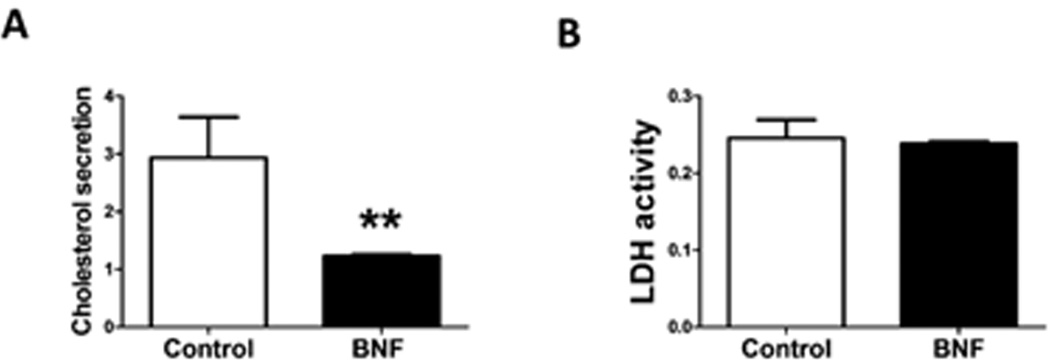

Cholesterol synthesis is repressed in primary human hepatocytes following AHR activation

Based on our findings, one might speculate that the decrease in the expression of all cholesterol synthesis genes examined in mice and humans would result in a lowered cholesterol synthesis and subsequent secretion. For this purpose, we treated primary human hepatocytes with BNF and used the GC-MS technique to quantify cholesterol in the media. As expected, treated cells showed a significant repression in the levels of secreted cholesterol indicating an overall regulation of the pathway by AHR (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Repression of cholesterol synthesis in primary human hepatocytes following AHR activation. (A) Synthesized cholesterol levels from media of BNF-treated cells compared to control cells are analyzed by GC-MS and normalized to an internal standard. (B) Cytotoxicity assay demonstrates cell viability is not affected by BNF treatment. Methods are described in the supplement.

Discussion

In the current study, we have established a transgenic mouse model that demonstrates the ability of AHR to modulate expression of a number of genes that encode for enzymes involved in the cholesterol synthetic pathway independent of DRE-binding leading to a repression in cholesterol secretion rate. There has been extensive interest in assessing the effect of TCDD exposure on serum lipid levels and more recently on the expression of lipid metabolism genes in rodents using microarrays 9, 10, but little progress has been made with regard to AHR modulation of those genes in vivo in the absence of exogenous ligand. Evolutionary conservation of the receptor coupled with the ahr-null mice phenotype suggests a role for the receptor beyond mediating xenobiotic metabolism. Differential constitutive expression of cholesterol biosynthesis genes between CreAlbAhrflox/flox mice and AHR-silenced human cell lines and their AHR expressing counterparts, as well as between Ahd and Ahb allele congenic mice suggests a function for the AHR in cholesterol homeostasis. Although, whether there is an endogeneous ligand(s) that mediates this effect is not known. Considering that cholesterol and oxysterols are involved in feedback regulation of cholesterol homeostasis, it will be important to test whether there are sterols that can act as AHR ligands. Indeed, 7-ketocholesterol is a key oxysterol present in serum that has been shown to be an AHR antagonist 24. Clearly, there is a need to examine the ability of other endogenous metabolites to act as AHR ligands and regulate cholesterol biosynthesis.

Circadian clocks synchronize the rhythmic activation of selective pathways in energy metabolism in mammalian tissues. Major metabolic pathways, including glucose and lipid metabolism as well as mitochondrial fuel oxidation, exhibit diurnal rhythms. Crosstalk between the AHR signaling pathway and the circadian rhythm is believed to occur 25. Concomitantly, AHR expression has been shown to take place in a circadian-dependent fashion displaying dual peaks. Superimposing the circadian expression of the AHR and the rate-limiting enzyme HMGCR reveals inverse peaks of expression 25, 26. This observation is in accordance with our results showing a higher expression of cholesterol biosynthetic enzymes with the absence of AHR both in vivo in mice, and in human cells. The integration of the circadian clock and energy metabolism and its ability to respond to a variety of exogenous stimuli, including chemical and metabolic signals, makes AHR a very likely candidate for genetic regulation of this lipid metabolic pathway. Our hypothesis for an adaptive endogenous role for the AHR is also supported by the fact that CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 are known to modulate cellular levels of a variety of lipid signaling molecules 27 and their high physiological levels observed in sections of human coronary arteries were shown to be an adaptive response to chronic arterial levels of shear stress 28. Furthermore, shear modified low-density lipoproteins (LDL) can lead to AHR activation in liver derived cell lines by an unknown mechanism; this observation would be consistent with a feedback regulation that attenuates cholesterol biosynthesis 29.

Our microarray and transgenic mouse studies show that the DRE-binding mutant AHR is still capable of modulating the expression of cholesterol synthesis genes upon ligand activation. Based on these observations coupled with the fact that SREBP2 levels remain unchanged both in mice and humans, one may speculate that AHR may be attenuating hepatic transcription of cholesterol biosynthetic genes through interaction with the transcription factor SREBP2 and/or through interference with co-factor recruitment. This hypothesis is supported by the ability of the AHR and SREBP2 to physically interact with other transcription factors and the physiological interaction between AHR and SREBP1 in T cells 30, 31. It is also worth noting that AHR has been shown to regulate the expression of CAR and FXR, nuclear receptors involved in the regulation of lipid synthesis 10, 32. Thus, it would be interesting to explore the possible involvement of these two receptors, along with the lipid-activated nuclear receptor PXR33, in AHR-mediated regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis.

Given that there is normally strict control over the rate of cholesterol synthesis, diseases caused by high serum cholesterol are treated with a low cholesterol diet coupled with drugs inhibiting this pathway. Statins, the most important class of lipid-lowering agents, are competitive inhibitors for the rate limiting enzyme, HMGCR. Nonetheless, in certain cases prolonged statin therapy has been associated with hepatotoxicity, rhabdomyolysis and compromised cardiac function 34. The side effects of statins, as well as the substantial numbers of people who either do not tolerate them or whose LDL levels are still significant have prompted the search for new drugs that target other cholesterol biosynthesis enzymes 22, 35.

Since the toxicity resulting from AHR activation is mediated through DRE-binding, the discovery that the AHR can coordinately attenuate the expression of cholesterol biosynthetic genes and subsequently cholesterol biosynthesis in a DRE independent manner is very an important observation. We have recently described that the AHR can be activated by selective Ah receptor modulators (SAhRM) to repress cytokine-mediated acute-phase gene expression in the liver, it will be important to test whether these compounds will also attenuate cholesterol biosynthesis 36. Thus, whether AHR can be used as a therapeutic target to repress the expression of cholesterol synthesis genes in vivo and thereby lower cholesterol synthesis rate inducing LDL receptors will require further investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant ES04869 and Bristol-Myers Squibb fellowship.

We thank Dr. Stephen C. Strom and Dr. Curtis J. Omiecinski for the primary human hepatocytes.

Abbreviations

- AHR

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ARNT

AHR nuclear translocator

- BNF

β-naphthoflavone

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DRE

dioxin response element

- FDFT1

farnesyldiphosphate farnesyltransferase

- HMGCR

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

- LSS

lanosterol synthase

- OSC

oxidosqualene cyclase

- SE or SQLE

squalene epoxidase

- SREBP2

sterol element binding protein 2

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- TTR

transtherytin promoter

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Chiaro CR, Morales JL, Prabhu KS, Perdew GH. Leukotriene A4 metabolites are endogenous ligands for the Ah receptor. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8445–8455. doi: 10.1021/bi800712f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dabir P, Marinic TE, Krukovets I, Stenina OI. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor is activated by glucose and regulates the thrombospondin-1 gene promoter in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1558–1565. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiNatale BC, Murray IA, Schroeder JC, Flaveny CA, Lahoti TS, Laurenzana EM, Omiecinski CJ, Perdew GH. Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115:89–97. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroeder JC, Dinatale BC, Murray IA, Flaveny CA, Liu Q, Laurenzana EM, Lin JM, Strom SC, Omiecinski CJ, Amin S, Perdew GH. The uremic toxin 3-indoxyl sulfate is a potent endogenous agonist for the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Biochemistry. 2010;49:393–400. doi: 10.1021/bi901786x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, Perdew GH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:207–250. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i3.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito S, Chen C, Satoh J, Yim S, Gonzalez FJ. Dietary phytochemicals regulate whole-body CYP1A1 expression through an arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-dependent system in gut. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1940–1950. doi: 10.1172/JCI31647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikuta T, Kawajiri K. Zinc finger transcription factor Slug is a novel target gene of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3585–3594. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel RD, Kim DJ, Peters JM, Perdew GH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor directly regulates expression of the potent mitogen epiregulin. Toxicol Sci. 2006;89:75–82. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato S, Shirakawa H, Tomita S, Ohsaki Y, Haketa K, Tooi O, Santo N, Tohkin M, Furukawa Y, Gonzalez FJ, Komai M. Low-dose dioxins alter gene expression related to cholesterol biosynthesis, lipogenesis, and glucose metabolism through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated pathway in mouse liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;229:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher N, Wahlstrom D, Lundberg R, Nilsson CB, Nilsson KC, Stockling K, Hellmold H, Hakansson H. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) alters the mRNA expression of critical genes associated with cholesterol metabolism, bile acid biosynthesis, and bile transport in rat liver: a microarray study. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishiumi S, Yabushita Y, Furuyashiki T, Fukuda I, Ashida H. Involvement of SREBPs in 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced disruption of lipid metabolism in male guinea pig. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;229:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuomisto JT, Pohjanvirta R, Unkila M, Tuomisto J. TCDD-induced anorexia and wasting syndrome in rats: effects of diet-induced obesity and nutrition. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62:735–742. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelclova D, Fenclova Z, Preiss J, Prochazka B, Spacil J, Dubska Z, Okrouhlik B, Lukas E, Urban P. Lipid metabolism and neuropsychological follow-up study of workers exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlordibenzo- p-dioxin. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2002;75(Suppl):S60–S66. doi: 10.1007/s00420-002-0350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robichon C, Dugail I. De novo cholesterol synthesis at the crossroads of adaptive response to extracellular stress through SREBP. Biochimie. 2007;89:260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett MK, Seo YK, Datta S, Shin DJ, Osborne TF. Selective binding of sterol regulatory element-binding protein isoforms and co-regulatory proteins to promoters for lipid metabolic genes in liver. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15628–15637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800391200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel RD, Murray IA, Flaveny CA, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. Ah receptor represses acute-phase response gene expression without binding to its cognate response element. Lab Invest. 2009;89:695–707. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsavsky KM, Page JL, Johnson MC, Zarbl H, Strom SC, Omiecinski CJ. Gene expression profiling and differentiation assessment in primary human hepatocyte cultures, established hepatoma cell lines, and human liver tissues. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;222:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiNatale BC, Schroeder JC, Francey LJ, Kusnadi A, Perdew GH. Mechanistic insights into the events that lead to synergistic induction of interleukin 6 transcription upon activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24388–24397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flaveny CA, Murray IA, Chiaro CR, Perdew GH. Ligand selectivity and gene regulation by the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor in transgenic mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1412–1420. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.054825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flaveny CA, Murray IA, Perdew GH. Differential gene regulation by the human and mouse aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Toxicol Sci. 2010;114:217–225. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine SL, Petrulis JR, Dubil A, Perdew GH. A tetratricopeptide repeat half-site in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor is important for DNA binding and trans-activation potential. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1517–1524. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlton-Menys V, Durrington PN. Squalene synthase inhibitors : clinical pharmacology and cholesterol-lowering potential. Drugs. 2007;67:11–16. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ugocsai P, Hohenstatt A, Paragh G, Liebisch G, Langmann T, Wolf Z, Weiss T, Groitl P, Dobner T, Kasprzak P, Gobolos L, Falkert A, Seelbach-Goebel B, Gellhaus A, Winterhager E, Schmidt M, Semenza GL, Schmitz G. HIF-1beta determines ABCA1 expression under hypoxia in human macrophages. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savouret JF, Antenos M, Quesne M, Xu J, Milgrom E, Casper RF. 7-ketocholesterol is an endogenous modulator for the arylhydrocarbon receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3054–3059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimba S, Watabe Y. Crosstalk between the AHR signaling pathway and circadian rhythm. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:560–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acimovic J, Fink M, Pompon D, Bjorkhem I, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P, Golicnik M, Rozman D. CREM modulates the circadian expression of CYP51, HMGCR and cholesterogenesis in the liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choudhary D, Jansson I, Stoilov I, Sarfarazi M, Schenkman JB. Metabolism of retinoids and arachidonic acid by human and mouse cytochrome P450 1b1. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:840–847. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conway DE, Sakurai Y, Weiss D, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Jo H, Eskin SG, Marcus CB, McIntire LV. Expression of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in human endothelial cells: regulation by fluid shear stress. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:669–677. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMillan BJ, Bradfield CA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is activated by modified low-density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1412–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607296104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui G, Qin X, Wu L, Zhang Y, Sheng X, Yu Q, Sheng H, Xi B, Zhang JZ, Zang YQ. Liver X receptor (LXR) mediates negative regulation of mouse and human Th17 differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:658–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI42974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett MK, Ngo TT, Athanikar JN, Rosenfeld JM, Osborne TF. Co-stimulation of promoter for low density lipoprotein receptor gene by sterol regulatory element-binding protein and Sp1 is specifically disrupted by the yin yang 1 protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13025–13032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel RD, Hollingshead BD, Omiecinski CJ, Perdew GH. Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor activation regulates constitutive androstane receptor levels in murine and human liver. Hepatology. 2007;46:209–218. doi: 10.1002/hep.21671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handschin C, Meyer UA. Regulatory network of lipid-sensing nuclear receptors: roles for CAR, PXR, LXR, and FXR. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiortsis DN, Filippatos TD, Mikhailidis DP, Elisaf MS, Liberopoulos EN. Statin-associated adverse effects beyond muscle and liver toxicity. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foley KA, Simpson RJ, Jr, Crouse JR, 3rd, Weiss TW, Markson LE, Alexander CM. Effectiveness of statin titration on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high risk of atherogenic events. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:79–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray IA, Krishnegowda G, DiNatale BC, Flaveny C, Chiaro C, Lin JM, Sharma AK, Amin S, Perdew GH. Development of a selective modulator of aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor activity that exhibits anti-inflammatory properties. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:955–966. doi: 10.1021/tx100045h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.